Abstract

Background

Preference differences between countries and populations justify the use of country-specific value sets for the EQ-5D instruments. There are no clear criteria based on which the selection of value sets for countries without a national value set should be made. As part of the European PECUNIA project, this study aimed to identify factors contributing to differences in preference-based valuations and develop supra-national value sets for homogenous country clusters in Europe.

Methods

A literature review was conducted to identify factors relevant to variations in the EQ-5D-3L/5L health state valuations across countries. Factors fulfilling the pre-specified criteria of validity, reliability, international feasibility and comparability were used to group 27 European Union member states, the European Free Trade Association countries and the UK. Clusters of countries were developed based on the frequency of their appearance in the same grouping. The supra-national value sets were estimated for these clusters from the coefficients of existing published valuation studies using the ordinary least-squares model.

Results

Ten factors were identified from 69 studies. From these, five grouping variables: (1) culture and religion; (2) linguistics; (3) healthcare system typology; (4) healthcare system financing; and (5) sociodemographic aspects were derived to define the groups of homogenous countries. Frequency-based grouping revealed five cohesive clusters: English-speaking, Nordic, Central-Western, Southern and Eastern European.

Conclusions

European countries were clustered considering variables that may relate to differences in health state valuations. Supra-national value sets provide optimised proxy value set selection in the lack of a national value set and/or for regional decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Our literature review suggests that factors representing cultural beliefs, religion, language, healthcare systems (typology, type of financing) and sociodemographics are associated with differences in preference-based health state valuations for the EQ-5D instruments. |

Five clusters of European countries that are likely to share similar characteristics relevant to preference-based health state valuations were identified: English speaking, Nordic, Central-Western, Southern and Eastern European, for which supra-national value sets, i.e. combining a selection of country-specific value sets, were estimated. |

The supra-national value sets could be used as a best approximate value set for countries that lack one as well as in multi-national trials and regional decision making to improve the comparability and transferability of outcome assessments in economic evaluations in Europe. |

Our method of developing clusters of countries can be applied to other preference-based health-related quality-of-life instruments. |

1 Introduction

The quality-adjusted life-year is calculated by multiplying the duration spent in a health state by the weight of health-related quality of life for this health state [1]. The value of the health-related quality of life can be estimated using questionnaires in those countries, which have already elicited a set of preference weights, often referred to as ‘value sets’ or ‘value tariffs’ [1]. The HUI, 15D, SF-6D and EQ-5D instruments (EQ-5D-3L/EQ-5D-5L and EQ-5D-Y-3L) are examples of such questionnaires, of which the EQ-5D-3L is the most frequently used instrument. The value sets for these measures are usually obtained from a sample of people representative of the country’s general population [2].

There are substantial differences between the existing value sets for the EQ-5D-3L/5L [3,4,5], which are often attributed to societal and cultural differences between countries [6,7,8,9], which justify the use of country-specific value sets [2]. However, some countries do not have their own national value sets, which hinders the conduct of robust economic evaluations in a national context and the cross-country comparability of measurement and valuation of outcomes. In addition, with regard to the ‘youth’ version of the EQ-5D, EQ-5D-Y-3L, only three value sets are currently available in Europe [10,11,12]. Of the 27 European Union member states plus Switzerland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland, countries of the European Free Trade Association, and the UK, 16 do not have any valuation set for the 3L or 5L versions of the EQ-5D (Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Iceland, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Slovakia, Norway, Switzerland). The number of countries having a value set in this region is likely to change as, for instance, Norway is expected to have their first value sets soon [13]. It is currently common practice to use the UK value sets as they are often described as an “accepted approximation” [14], “recommended as most robust” [15] and “most commonly used” [16]. In some countries lacking national value sets, the health technology assessment guidelines for conducting cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses recommend to apply the UK value sets [13, 17]. Our own research conducted prior to this study showed that from 2010 to 2019 the most commonly used value sets in these countries were the UK or European visual analogue scale [18] value sets (Fig. A1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). However, there is a lack of evidence supporting the choice of one particular substitute value set as the best possible approximation of the target population. In addition to this, with the emerging number of new instruments, the need to borrow value sets across countries is likely to become a continually relevant topic.

To address the issue of the lack of value sets in some countries and explore the heterogeneity that might stem from cultural and contextual factors, we propose the development of supra-national value sets for the EQ-5D instruments. In addition to providing the best possible proxy value sets for countries that lack one, supra-national value sets are increasingly needed for comparability in multi-national studies and in regional procurement settings, for example for drug pricing and reimbursement. Many initiatives have emerged at the European level ensuring access to safe, effective, high-quality and affordable essential medicines [19]. Regional initiatives such as Beneluxa, the Velletta Declaration, the Balti Procurement Initiative and the Nordic Pharmaceutical Forum [19] aim to exchange strategic information and to help in joint negotiations in the context of drug reimbursement and pricing. These collaborations are likely to drive further cross-border collaborations and evidence-based decision making, such as jointly written health technology assessment reports.

Hence, the aim of this study was, first, to identify relevant factors attributed to differences in preference-based health state valuations with the EQ-5D in order to establish a conceptual framework for the development of supra-national value sets in Europe. The second objective was to estimate supra-national value sets for homogenous country clusters in Europe with respect to these contributing factors.

2 Methods

2.1 Development of a Conceptual Framework

The approach adopted in the development of the conceptual framework consisted of four steps. First, information from peer-reviewed literature was collected to identify factors influencing the EQ-5D instrument health state valuations. Second, the identified factors were assessed for their suitability to cluster development against pre-selected criteria. Next, the selection of grouping variables was made based on existing classifications and the countries were assigned into relevant categories within these grouping variables. Finally, clusters of homogenous countries were developed based on the frequency of their appearance in the same grouping category.

2.2 Literature Review

A targeted review of health economic literature relating to the EQ-5D instrument (EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-5L) health state valuations was conducted between October 2019 and December 2019 and updated in May 2020. The objective of the review was to identify which factors influenced differences in the EQ-5D instrument health state valuations across populations. Although the focus of this study was on the 27 European Union member states plus European Free Trade Association countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) and the UK, the literature review was not restricted to European countries, neither was it limited to any languages or time period to allow a comprehensive assessment of all potential factors as per the exploratory character of this study. The search was undertaken in four databases: Embase, MEDLINE, Econlit, and the Social Sciences Citation Index. The search strategy is illustrated in Table A1 of the ESM. Articles were also obtained by searching reference lists of the identified studies and hand searching the EuroQol Group’s website (https://euroqol.org/) as part of the grey literature search. One researcher screened the titles and abstracts and then full texts of the identified studies. All studies that either empirically studied differences in how people valued the EQ-5D-3L/5L hypothetical states based on their country of origin or other characteristics (e.g. ethnicity, socio-economic status) or considered these aspects as part of their discussion were included as eligible. Extracted information on potential factors contributing to differences in preference-based valuations with the EQ-5D instruments was collated in a tabulated format, summarised and analysed in the next steps.

2.3 Assessment of Identified Factors for Their Suitability for Cluster Development

The identified factors were assessed for their suitability and relevance in generating groups of comparable countries for the development of supra-national value sets. The assessment was made based on a modified list of criteria originally proposed by Carinci et al. to score health system performance indicators for international comparisons [20]. Four out of six originally proposed criteria were used and adapted for the purpose of this study: (1) validity; (2) reliability; (3) international feasibility; and (4) international comparability (Table A2 of the ESM). The two criteria of ‘Relevance’ and ‘Actionability’ were not applied as they referred to aspects of clinical relevance and quality of care, which were deemed not applicable for this study [20]. In the current context, a factor was considered valid, if empirical scientific evidence was found to support the link between the factor and the variations in the EQ-5D-3L/5L health state valuations. Factors were considered reliable, if their assigned country-specific values represented stable phenomena and were not subjected to frequent changes over time. For instance, examples of factors that would not fulfil these criteria could be unemployment rates. International feasibility meant that values of a factor could be easily derived for international comparisons, while international comparability meant that the definition of the factor is uniform across countries.

The assessment of identified factors was made by the authors following the information extracted from the literature. A three-point scoring was applied per criterion depending on if the variable (1) met the criterion (1 point), (2) partially met the criterion (0.5 point) or (3) did not meet the criterion at all (0 point). Those factors that met all four criteria fully (1 point) or partly (0.5 point) and reached a sum of more than 2, were chosen for the further development of grouping variables.

2.3.1 Categorisation of Countries Based on Final Grouping Variables

The aim was to categorise countries into groups based on factors that met the criteria. Grouping variables that reflected these factors needed to be operationalised. We adopted a process of a non-systematic literature search to identify practical classifications that matched the selected factors and could be used as grouping variables. The search was conducted in PubMed and Google without time restrictions using keywords representing the factors (e.g. religion) and possible practical classifications (exemplary keywords: “classification”, “categorisation”, “grouping”, “division”, “classifying system”). After selecting relevant classifications as grouping variables, countries were assigned to different categories.

2.3.2 Cluster Development

The frequency with which pairs of countries within the same category appeared in a particular grouping variable was counted and depicted graphically. Based on these frequencies, clusters of countries were derived. To account for the uncertainty around the selection of grouping variables, different scenarios for deriving supra-national clusters were applied, each time omitting one of the grouping variables to observe the impact on the resulting clusters.

2.4 Development of Supra-National Value Sets

Supra-national value sets combined country-specific value sets derived using the same methodology, i.e. time trade-off (TTO) for the EQ-5D-3L (France, Germany, The Netherlands, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, UK, Denmark), and standardised EQ-VT protocol for the EQ-5D-5L (France, Germany, The Netherlands, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Hungary, Poland, Denmark, Ireland). Methodological aspects of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L valuation studies were compared in Tables A3 and A4 of the ESM.

Coefficients from published national valuation studies were used to derive ‘saturated value sets’ for both the EQ-5D-3L and the EQ-5D-5L using the methodology developed by Sajjad et al. [21]. Saturated value sets contained utility values for all 243 (35) or 3125 (55) theoretical health states for each country included in the supra-national cluster for the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L, respectively [22].

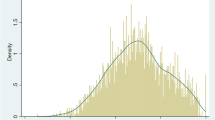

Several approaches to model these simulated data were tested including ordinary least-squares, tobit, generalised linear model with gamma log-link and Finite mixture models as well as models with interaction terms (N3, D1, I2, I32). Goodness-of-fit statistics were compared including the Bayesian information criterion, Akaike information criterion, root mean square error and pseudo-R2. The ordinary least-squares model was the best fitting and most pragmatic. Hence, the ordinary least-squares regression analysis was used to estimate the pooled cluster value sets. The dependent variable was the utility value for all 243 or 3125 health states for each country for the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L, respectively, with the best health state having the upper bound at 1 and 0 being dead. The regressors were constructed as dummy variables to model the shift between the five and three levels of the EQ-5D-5L and EQ-5D-3L descriptive systems within each of the five dimensions, respectively. Thus, for the EQ-5D-5L, four dummy variables were constructed for the Mobility dimension (MO): one measuring the shift between level 1 and level 2 (MO2); one measuring the shift between level 2 and level 3 (MO3), one measuring the shift between level 3 and level 4 (MO4); and one measuring the shift between level 4 and level 5 (MO5). Similar dummy variables were constructed for the dimensions of: self-care (SC2, SC3, SC4, SC5); usual activities (UA2, UA3, UA4, UA5); pain/discomfort (PD2, PD3, PD4, PD5) and anxiety/depression (AD2, AD3, AD4, AD5). Similarly, for the EQ-5D-3L, two dummy variables were constructed for the Mobility dimension: one measuring the shift between level 1 and level 2 (MO2) and one measuring the shift between level 2 and level 3 (MO3). Again, similar dummy variables were constructed for the dimensions of: self-care (SC2, SC3); usual activities (UA2, UA3); pain/discomfort (PD2, PD3) and anxiety/depression (AD2, AD3).

3 Results

3.1 Literature Review

Searches of the databases generated 881 references which, after de-duplication, amounted to 506 unique records. An additional 38 potentially relevant studies were retrieved from the reference lists of identified studies and four additional studies were obtained through a grey literature search. Following the screening of titles and abstracts and then the full texts of potentially eligible studies, 69 articles were included for data extraction (Fig. A2 of the ESM). We found 31 empirical studies that had an explicit aim to explore differences in how people value different health states based on their country of origin or other characteristics, for example, ethnicity and socio-economic status. The remaining studies (n = 38) included comparisons of value sets, conceptual/methodological articles, and articles exploring how valuation tariffs impact quality-adjusted life-years (Table A5 of the ESM).

3.2 Assessment of the Identified Factors and Proposed Grouping Variables

Ten factors that contribute to differences in the EQ-5D-3L/5L value sets were extracted: cultural differences, language differences/translation issues, methodological differences of the value set development, healthcare system differences (healthcare system typology, financing system), economic differences, sociodemographic differences, religion, racial/ethnic differences, geographical proximity and environmental differences (Fig. 1). The majority of the identified studies (70%) were concerned with the 3L version of the EQ-5D. At the time of the review, no value set for the EQ-5D-Y-3L was available.

Following the assessment of the identified factors for their relevance in cluster development, the variables that reached the cut-off score of 2 and had no “0” values were: cultural differences, religion, language, healthcare system typology, healthcare system financing and sociodemographic aspects (Table 1). The variables ethnicity, economic status, geographical proximity and environmental factors were excluded because of their potential weaknesses with respect to validity (i.e. no concrete evidence was found that these variables influence health state valuations) and reliability (i.e. they might not represent a stable phenomenon over time).

3.3 Culture and Religion: Grouping Variable 1

Several studies highlight that those countries that are culturally alike are also likely to value health more similarly compared to countries with substantially varying cultural backgrounds [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Studies that were reviewed in the literature search showed that using Hoftede’s definition of culture produced mixed results with respect to health state valuations [23,24,25], suggesting that a different definition of culture/cultural beliefs should be adopted. Therefore, in this study, the work of Huntingdon [30] and Inglehart and Baker [31] was used to define the first grouping variable. Following their thesis that the cultural heritage of a society is shaped by religious traditions, eight “cultural zones” were established, of which five were relevant for Europe: English-speaking, Protestant Europe, Catholic Europe, Baltic and Orthodox. Inglehart and Baker added one additional “Ex-communist” zone (Table 2). This extended classification was considered most accurate in the context of this study, which included former communist states. Our review also showed that religious aspects are important in the context of health state valuations [32,33,34,35].

3.4 Language: Grouping Variable 2

The literature search showed that linguistic variations influenced how respondents interpreted and valued health states [26, 35,36,37,38,39,40]. Studies found, for instance, that labels used in the Likert scale of the EQ-5D may be interpreted differently in different languages [37] or the nuances in the wording, especially the labels of the levels, might be different in different languages [35, 36]. There are over 140 languages present in Europe [41]. Indo-European languages are most often spoken such as Romance, Germanic, Slavic, Baltic and Greek languages. Other languages include, for example, West-Central semitic (e.g. Maltese) or Uralic (e.g. Finnish, Estonian, Hungarian) [42]. Table 2 shows the distribution of languages spoken in Europe upon which the second grouping variable was determined.

3.5 Healthcare System Typology: Grouping Variable 3

Studies have shown that the organisation of healthcare systems, including social support systems, could be a factor associated with assigning different preference values to given health states in valuation studies [33, 43,44,45]. For instance, Devlin et al. reported that some respondents’ valuations of hypothetical states are contingent on access to appropriate care and support for the person in that state [33]. Healthcare system typology was considered as the next relevant and suitable grouping variable in this study. A recent study by Ferreira et al. proposed a new classification of the healthcare systems in the European Union. Their investigation was based on methods including factor and cluster analyses to identify relevant healthcare system type categories [46] that were adopted in this study (Table 2).

3.6 Healthcare System Financing: Grouping Variable 4

The fourth grouping variable reflected the healthcare system classification of the OECD countries described by Böhm et al. and Wendt et al. [47, 48] (Table 2). This classification was extracted from the publication of Ferreira et al. [46] who provided an overview of existing healthcare system typologies. The classification distinguished dimensions of healthcare systems with respect to regulation, financing and service provision by three types of actors, namely state, societal and private. Healthcare system financing was included as an independent variable because it might play an important role in assigning preference values to given health states. For instance, a study showed that Singaporean Chinese had greater disutility for very poor health states compared with mainland Chinese [44]. The authors explained that in mainland China, a substantial percentage of health expenses are covered by health insurance in contrast to Singaporean participants who commented that they would prefer to die rather than become a burden to their families [44].

3.7 Sociodemographic Factors: Grouping Variable 5

The last grouping variable was based on a premise that sociodemographic aspects are associated with differences in preferences for different health states, including poverty status [49], geographical country region [49, 50], study site (urban vs rural areas) [45, 50], level of education attained [27, 49], marital status [50, 51], sex [52] and age [51, 52]. According to Dolan, age, marital status and sex emerge as three of the most important factors that might explain TTO values [53]. The fifth grouping variable was derived based on a study by Palevičien and Dumčiuvienė that used 25 regional indicators to identify clusters of countries with sociodemographic similarity within the European Union [54]. Because of the fact that some countries relevant to this study were not included in the original classification derived from Palevičien and Dumčiuvienė, these countries were assigned to the respective categories based on the similarities identified in another classification provided by Figueras et al. [55] and Genova [56] (extracted from the publication of Ferreira et al. [46]) [Table 2].

3.8 Selection of Clusters

The frequency with which pairs of countries have been grouped in the same category within a respective grouping variable is shown in Table A6 of the ESM. Figure 2 presents the links between all pairs of countries that were assigned to the same category three, four or five times. The thickness and colour of the connecting line between the countries depend on the number of times these countries were assigned to the same category. If pairs of countries appeared in the same category twice or only once, these interactions are not shown for simplicity. For example, Sweden and Denmark appeared in the same category on five out of five occasions within the respective country cluster, which is represented by the thickest black line. The analysis of these frequencies revealed five cohesive clusters: English speaking, Nordic, Central-Western, Southern and Eastern European. The Central-Western cluster currently combines the value sets from Germany, France and The Netherlands both for the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L. The Southern cluster consists of the value set from Portugal, Spain and Italy for the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L. The Eastern European cluster consists of the value sets from Poland, Hungary, Romania and Slovenia for the EQ-5D-3L and from Poland and Hungary for the EQ-5D-5L. The UK value sets for the EQ-5D-3L and Irish value set for the EQ-5D-5L are available in the English-speaking cluster. The Nordic cluster has currently one value set from Denmark for the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L (Table 3).

Identified country clusters for the development of supra-national value sets. Figure 2 presents links between all pairs of countries that were assigned to the same category within grouping variables presented in Table 2 three times (light grey), four times (dark grey) or five times (black). 3L EQ-5D-3L, 5L EQ-5D-5L, AUT Austria, BEL Belgium, BUL Bulgaria, CRO Croatia, CYP Cyprus, CZE Czech Republic, DEN Denmark, EST Estonia, FIN Finland, FRA France, GER Germany, GRE Greece, HUN Hungary, ICE Iceland, IRE Ireland, ITA Italy, LAT Latvia, LIT Lithuania, LUX Luxembourg, MAL Malta, NED The Netherlands, NOR Norway, POL Poland, POR Portugal, ROM Romania, SLO Slovakia, SLV Slovenia, SPA Spain, SWE Sweden, SWI Switzerland, TTO time trade-off

3.9 Sensitivity Analysis of the Cluster Selection

Six scenarios for the sensitivity analysis were analysed to observe the impact of selected grouping variables on the proposed clusters (Figs. A3–A8 of the ESM): in Scenarios 1–5, one of the grouping variables was omitted and the frequency of country links re-calculated. In Scenario 6, countries that were not included in the original classification systems of the given grouping variables (marked in italics in Table 2), were removed.

The analysis revealed that the (sub)cluster consisting of Cyprus and Greece was most affected when one of the grouping variables was removed from the frequency analysis. In three out of five sensitivity analysis scenarios, these two countries became a separate cluster not connected to the Southern cluster. In three out of five scenarios, Liechtenstein was separated from the Western cluster and Croatia from the Eastern European cluster. In one scenario, Croatia and Slovenia as well as Latvia and Lithuania created separate two-country clusters. Next to these differences, the proposed clusters remained unchanged irrespective of the scenario applied.

3.10 Supra-National Value Sets

All EQ-5D-3L TTO value sets included in the development of supra-national value sets with the exception of Hungary and Romania followed the Measurement and Valuation of Health protocol, which was developed in the UK to elicit health state preferences from the EQ-5D using the TTO method [57]. Most of the countries modified the Measurement and Valuation of Health protocol especially with respect to the number of health states valued directly by the respondents and the number of health states valued by each respondent. In Romania and Hungary, only three health states were valued by each respondent. With respect to the EQ-5D-5L, the differences between the methodologies of the valuation studies were less notable. Italy differed from other studies with respect to the mode of administration and used videoconferencing because of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Two countries, The Netherlands and Hungary, estimated their value sets using only the TTO data, while the remaining countries opted for the hybrid model.

Supra-national value sets for three clusters (Central-Western, Southern, Eastern-European) are presented in Tables 4 and 5. For the two remaining clusters where currently a value set from only one country is available (English speaking, Nordic), this given value set may be recommended as the best proxy to be used by other countries within the same cluster. In the calculated supra-national value sets, the constant is interpreted as the utility decrement associated with any deviation from full health. Whenever the constant is different than 1 (all supra-national value sets except the EQ-5D-5L from the Southern and Eastern European clusters), it should be used in the calculation of the EQ-5D index. For instance, the EQ-5D-3L index for the Central-Western cluster for the health state 33333 can be calculated using the following formula: 33333 = 1 − 0.183 (1 − constant) − 0.325 − 0.255 − 0.119 − 0.340 − 0.236.

3.11 Comparison of National and Supra-National Value Sets

The analysis of differences between the national value sets included in the study as well as supra-national value sets is provided in Tables A7–A9 of the ESM.

3.11.1 National Value Sets

The MO dimension was given the most importance (in terms of disutility for the worst level within a dimension) in the majority of the EQ-5D-3L value sets with the exception of The Netherlands, Poland and the UK, while PD was ordered as most important in most of the countries for the EQ-5D-5L. The number of health states worse than death varied from 21 (Italy) to 91 (Spain) for the EQ-5D-3L and from 206 (Poland) to 1124 (Ireland) for the EQ-5D-5L. Across all EQ-5D-5L value sets, the largest differences in the disutility values were assigned to the AD dimension. The loss of utility in level three of AD (AD3) was six times lower for the Irish respondents (disutility of − 0.202) than for the Polish respondents (disutility of − 0.029), which confirms that these two countries should be assigned to different clusters. The next largest relative differences were observed between Poland (− 0.018) and Spain (− 0.081) in AD2, Poland (− 0.108) and Ireland (− 0.535) in AD5 and France (− 0.022) and Spain (− 0.075) in AD5.

3.11.2 Supra-National Value Sets

For the EQ-5D-3L supra-national value sets, the number of health states worse than death ranged from 40 in the Eastern European cluster to 84 in the English-speaking cluster. The most important dimensions in terms of the lowest utilities assigned to level 3 were PD in the CW and English-speaking clusters and MO in the remaining clusters. The UA dimension was the least important in all clusters with the exception of the Southern cluster. AD was more important in the English-speaking and Nordic clusters compared with all remaining clusters, confirming that there are differences between the regions.

With respect to the EQ-5D-5L supra-national value sets, the number of health states worse than death ranged from 308 in the Southern cluster to 1124 in the English-speaking cluster. PD was the most important dimension in the CW, Southern and EE clusters, while AD had the highest significance in the English-speaking and Nordic clusters. UA was determined to be the least important in all EQ-5D-5L clusters.

4 Discussion

This work is part of the PECUNIA project that aimed at developing harmonised methods for a cost and outcome assessment for multi-sectoral, multi-national, multi-person economic evaluations in Europe [58]. The study contributed to that aim by improving the comparability and transferability of the outcome assessment in economic evaluations considering issues with availability and variability of the EQ-5D-3L/5L value sets across European countries. On the basis of the existing literature, five country clusters cohesive in terms of potential factors influencing the preference-based health state valuation for the EQ-5D instruments were proposed, and the resulting supra-national value sets were presented.

In addition to deriving clusters for the supra-national value sets, this study contributes to understanding the rationale behind using different substitute value sets in countries without one. Currently, the common practice is to use the UK value sets. However, there is a lack of evidence that would support this particular substitution, as the best possible approximation for the target population. For the clusters where more than one country-specific EQ-5D value set is available (Central-Western, Southern and Eastern European), a supra-national value could be used as the best proxy, if no national value set exists.

Another advantage of supra-national value sets is their potential usefulness in multi-national trials conducted within a given European region, and when regional reimbursement and drug pricing negotiations are considered. In multi-national economic evaluations, researchers tend to use a single or a limited number of value sets that are applied for all participating countries to derive utility values for quality-adjusted life-years (e.g. [59]). Using a single value set relevant to the region could increase the international comparability of economic evaluations across the included countries, while at the same time provide results that are in line with population health preferences. In the situation when all necessary value sets are available, their use should have priority before a combined value set.

Furthermore, the developed conceptual framework and the findings of the underlying literature review are not seen as limited to the European region and could be used for the future development of supra-national value sets in other regions of the world. For instance, several Asian countries have developed value sets for the EQ-5D instruments with comparable heterogeneity observed as in Europe [60]. A similar methodological approach could be also applied to other outcome measures, for example, the SF-6D and HUI, which have country-specific preference-based value sets available. A similar investigation in other regions should also include testing of other factors that could be relevant for the selected countries but were not included in the current study, for example, the regional differences in gross domestic product per capita.

Some limitations of the proposed approach need to be considered. The underlying assumption of this study is that countries grouped based on their broad characteristics for factors influencing a health state valuation should be fairly similar in terms of actual preferences. However, some studies showed that even when adjusting for these different factors, heterogeneity in preferences for health states remains [8, 25, 61,62,63]. In addition, there might be methodological variations in the sampling, the field administration and subsequent modelling of different national value sets that cause heterogeneity beyond the assessed country characteristics. Our investigation showed that the variations in the methodology of derivation of the national value sets were larger for the EQ-5D-3L valuation studies as compared with the EQ-5D-5L valuations. The EQ-5D-5L valuations followed a more strict protocol and a standardised independent quality-control system [64]. In the current study, we did not control for the methodological differences between the value sets. However, the value sets combined in the supra-national value sets used the same methodology of deriving health preferences, namely TTO or EQ-VT. Another limitation is that the differences in terms of the relevant factors for the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L were not examined separately in this study and the literature review conducted to identify factors did not follow a rigorous protocol of a systematic literature review (i.e. only one author conducted the screening procedure). Finally, the applied grouping variables and their historical categories may not reflect some ongoing dynamic demographic changes in Europe and will need to be revisited in the future. Previous studies noted that ethnicity and migrant/native status are related to differences in the utility valuations assigned to different health states [65,66,67]. However, in this study, ethnicity was not a feasible variable to group countries into categories. Future research should address this issue and provide guidelines on how to assess health state preferences in heterogeneous populations with consideration of ethnicity and migration status.

5 Conclusions

The European countries were clustered on the basis of variables contributing to differences in preference-based valuations with the EQ-5D instruments and supra-national value sets were estimated for these clusters. The supra-national value sets can be used when a national value set is not available and/or for regional decision making.

References

Whitehead SJ, Ali S. Health outcomes in economic evaluation: the QALY and utilities. Br Med Bull. 2010;96(1):5–21.

Rowen D, Azzabi Zouraq I, Chevrou-Severac H, van Hout B. International regulations and recommendations for utility data for health technology assessment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(Suppl 1):11–9.

Zrubka Z, Beretzky Z, Hermann Z, Brodszky V, Gulacsi L, Rencz F, et al. A comparison of European, Polish, Slovenian and British EQ-5D-3L value sets using a Hungarian sample of 18 chronic diseases. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(Suppl. 1):119–32.

Gerlinger C, Bamber L, Leverkus F, Schwenke C, Haberland C, Schmidt G, et al. Comparing the EQ-5D-5L utility index based on value sets of different countries: impact on the interpretation of clinical study results. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):18.

Lien K, Tam VC, Ko YJ, Mittmann N, Cheung MC, Chan KKW. Impact of country-specific EQ-5D-3L tariffs on the economic value of systemic therapies used in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Curr Oncol. 2015;22(6):e443–52.

Ali M, MacIsaac R, Quinn TJ, Bath PM, Veenstra DL, Xu Y, et al. Dependency and health utilities in stroke: data to inform cost-effectiveness analyses. Eur Stroke J. 2017;2(1):70–6.

Johnson JA, Luo N, Shaw JW, Kind P, Coons SJ. Valuations of EQ-5D health states: are the United States and United Kingdom different? Med Care. 2005;43(3):221–8.

Knies S, Evers SM, Candel MJ, Severens JL, Ament AJ. Utilities of the EQ-5D: transferable or not? Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(9):767–79.

Norman R, Cronin P, Viney R, King M, Street D, Ratcliffe J. International comparisons in valuing EQ-5D health states: a review and analysis. Value Health. 2009;12(8):1194–200.

Prevolnik Rupel V, Ogorevc M. EQ-5D-Y value set for Slovenia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(4):463–71.

Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Estévez-Carrillo A, Rivero-Arias O, Wolfgang G, Simone K, et al. Accounting for unobservable preference heterogeneity and evaluating alternative anchoring approaches to estimate country-specific EQ-5D-Y value sets: a case study using Spanish preference data. Value Health. 2022;25(5):835–43.

Kreimeier S, Mott D, Ludwig K, Greiner W, Prevolnik Rupel V, Ramos-Goñi JM, et al. EQ-5D-Y value set for Germany. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01143-9.

Hansen TM, Helland Y, Augestad LA, Rand K, Stavem K, Garratt A. Elicitation of Norwegian EQ-5D-5L values for hypothetical and experience-based health states based on the EuroQol Valuation Technology (EQ-VT) protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6): e034683.

Haragus H, Deleanu B, Prejbeanu R, Timar B, Levai C, Vermesan D. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Romanian Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score for Joint Replacement. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(4):307–11.

Svedbom A, Borgstom F, Hernlund E, Strom O, Alekna V, Bianchi ML, et al. Quality of life for up to 18 months after low-energy hip, vertebral, and distal forearm fractures: results from the ICUROS. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(3):557–66.

Ferreira LN, Ferreira PL, Pereira LN, Oppe M. The valuation of the EQ-5D in Portugal. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(2):413–23.

State Institute for Drug Control. Postup pro posuzování analýzy nákladové efektivity. Verze: 5. 2022. Available from: https://www.sukl.cz/file/97943_1_1. Accessed 9 Aug 2022.

Greiner W. A European EQ-5D VAS valuation set. In: Brooks R, Rabin R, de Charro F, editors. The measurement and valuation of health status using EQ-5D: a European perspective: evidence from the EuroQol BIOMED Research Programme. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2003. p. 103–42.

World Health Organization. Cross-country collaborations to improve access to medicines and vaccines in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen. 2020. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332933. Accessed 9 Aug 2022.

Carinci F, Van Gool K, Mainz J, Veillard J, Pichora EC, Januel JM, et al. Towards actionable international comparisons of health system performance: expert revision of the OECD framework and quality indicators. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(2):137–46.

Sajjad A, Versteegh M, van Busschbach J, Simon J, Hakkaart-van RL. In search of a pan-European value set; application for EQ-5D-3L: the PECUNIA project. Value Health. 2019;22:S815.

Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care. 1997;35(11):1095–108.

Mahlich J, Dilokthornsakul P, Sruamsiri R, Chaiyakunapruk N. Cultural beliefs, utility values, and health technology assessment. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2018;16:19.

Bailey H, Kind P. Preliminary findings of an investigation into the relationship between national culture and EQ-5D value sets. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(8):1145–54.

Roudijk B, Donders ART, Stalmeier PFM. Cultural values: can they explain differences in health utilities between countries? Med Decis Mak. 2019;39(5):605–16.

Luo N, Wang Y, How CH, Wong KY, Shen L, Tay EG, et al. Cross-cultural measurement equivalence of the EQ-5D-5L items for English-speaking Asians in Singapore. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(6):1565–74.

Jin X, Liu GG, Luo N, Li H, Guan H, Xie F. Is bad living better than good death? Impact of demographic and cultural factors on health state preference. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(4):979–86.

Xie F, Pullenayegum E, Pickard AS, Ramos Goñi JM, Jo MW, Igarashi A. Transforming latent utilities to health utilities: East does not meet West. Health Econ. 2017;26(12):1524–33.

Feng Y, Herdman M, van Nooten F, Cleeland C, Parkin D, Ikeda S, et al. An exploration of differences between Japan and two European countries in the self-reporting and valuation of pain and discomfort on the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(8):2067–78.

Huntingdon S. The clash of civilizations. Foreign Aff. 1993;72(3):22–49.

Inglehart R, Baker WE. Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am Sociol Rev. 2000;65(1):19–51.

Barry L, Hobbins A, Kelleher D, Shah K, Devlin N, Goni JMR, et al. Euthanasia, religiosity and the valuation of health states: results from an Irish EQ5D5L valuation study and their implications for anchor values. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):152.

Devlin NJ, Hansen P, Selai C. Understanding health state valuations: a qualitative analysis of respondents’ comments. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(7):1265–77.

Jakubczyk M, Golicki D, Niewada M. The impact of a belief in life after death on health-state preferences: true difference or artifact? Qual Life Res. 2016;25(12):2997–3008.

Papadimitropoulos EA, Elbarazi I, Blair I, Katsaiti MS, Shah KK, Devlin NJ. An Investigation of the feasibility and cultural appropriateness of stated preference methods to generate health state values in the United Arab Emirates. Value Health Reg Issues. 2015;7:34–41.

Badia X, Roset M, Herdman M, Kind P. A comparison of United Kingdom and Spanish general population time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states. Med Decis Mak. 2001;21(1):7–16.

Luo N, Wang Y, How CH, Tay EG, Thumboo J, Herdman M. Interpretation and use of the 5-level EQ-5D response labels varied with survey language among Asians in Singapore. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(10):1195–204.

Craig BM, Monteiro AL, Herdman M, Santos M. Further evidence on EQ-5D-5L preference inversion: a Brazil/US collaboration. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(9):2489–96.

Luo N, Ko Y, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. The association of survey language (Spanish vs. English) with Health Utilities Index and EQ-5D index scores in a United States population sample. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(10):1377–85.

Luo N, Li M, Chevalier J, Lloyd A, Herdman M. A comparison of the scaling properties of the English, Spanish, French, and Chinese EQ-5D descriptive systems. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(8):2237–43.

Haarmann H. Europe’s mosaic of languages. 2011. Available from: http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/crossroads/mosaic-of-languages. Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

Van der Auwera J, Baoill DÓ. Adverbial constructions in the languages of Europe. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter; 1998.

Szende A, Janssen B, Cabases J. Self-reported population health: an international perspective based on EQ-5D. Dordrecht: Springer; 2014.

Wang P, Li MH, Liu GG, Thumboo J, Luo N. Do Chinese have similar health-state preferences? A comparison of mainland Chinese and Singaporean Chinese. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(8):857–63.

Xie F, Gaebel K, Perampaladas K, Doble B, Pullenayegum E. Comparing EQ-5D valuation studies: a systematic review and methodological reporting checklist. Med Decis Mak. 2014;34(1):8–20.

Ferreira PL, Tavares AI, Quintal C, Santana P. EU health systems classification: a new proposal from EURO-HEALTHY. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):511.

Böhm K, Schmid A, Götze R, Landwehr C, Rothgang H. Five types of OECD healthcare systems: empirical results of a deductive classification. Health Policy. 2013;113(3):258–69.

Wendt C, Frisina L, Rothgang H. Healthcare system types: a conceptual framework for comparison. Soc Policy Adm. 2009;43(1):70–90.

Gaskin DJ, Frick KD. Race and ethnic disparities in valuing health. Med Decis Mak. 2008;28(1):12–20.

Sayah FA, Bansback N, Bryan S, Ohinmaa A, Poissant L, Pullenayegum E, et al. Determinants of time trade-off valuations for EQ-5D-5L health states: data from the Canadian EQ-5D-5L valuation study. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(7):1679–85.

Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Chen S, Levin JR, Coons SJ. Racial/ethnic differences in preferences for the EQ-5D health states: results from the US valuation study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(5):479–90.

Bernert S, Fernandez A, Haro JM, Konig HH, Alonso J, Vilagut G, et al. Comparison of different valuation methods for population health status measured by the EQ-5D in three European countries. Value Health. 2009;12(5):750–8.

Dolan P. The effect of experience of illness on health state valuations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(5):551–64.

Palevičienė A, Dumčiuvienė D. Socio-economic diversity of European regions: finding the impact for regional performance. Proc Econ Financ. 2015;23:1096–101.

Figueras J, Mossialos E, McKee M, Sassi F. Health care systems in Southern Europe: is there a Mediterranean paradigm? Int J Health Sci. 1994;5(4):135–46.

Genova A. Health regimes: a proposal for comparative studies. In: Giarelli G, on behalf of European Society for Health and Medical Sociology, editor. Comparative research methodologies in health and medical sociology: Salute e Società, IX, 2/2010. Milan: Franco Angeli Edizioni; 2010. p. 167

Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. The time trade-off method: results from a general population study. Health Econ. 1996;5(2):141–54.

Simon J, Konnopka A, Brodszky V, Evers S, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Serrano Aguilar P, et al., editors. (Pharmaco)economic evaluations for mental health related services: the PECUNIA project. In: 6th World Congress on Public Health; 12–17 October, 2020; Rome.

Richardson J, Khan MA, Iezzi A, Maxwell A. Comparing and explaining differences in the magnitude, content, and sensitivity of utilities predicted by the EQ-5D, SF-6D, HUI 3, 15D, QWB, and AQoL-8D multiattribute utility instruments. Med Decis Mak. 2015;35(3):276–91.

Wang P, Liu GG, Jo MW, Purba FD, Yang Z, Gandhi M, et al. Valuation of EQ-5D-5L health states: a comparison of seven Asian populations. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19(4):445–51.

Dolan P, Roberts J. To what extent can we explain time trade-off values from other information about respondents? Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(6):919–29.

Heijink R, van Baal P, Oppe M, Koolman X, Westert G. Decomposing cross-country differences in quality adjusted life expectancy: the impact of value sets. Popul Health Metr. 2011;9(1):17.

Poudel N, Ngorsuraches S, Qian J, Garza K. Methodological variations among health state valuation studies using EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review. Value Health. 2019;22:S319–20.

Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Slaap B, Busschbach JJ, Stolk E. Quality control process for EQ-5D-5L valuation studies. Value Health. 2017;20(3):466–73.

Kelleher D, Barry L, Hobbins A, O’Neill S, Doherty E, O’Neill C. Examining the transnational health preferences of a group of Eastern European migrants relative to a European host population using the EQ-5D-5L. Soc Sci Med. 2020;246: 112801.

Pickard AS, Tawk R, Shaw JW. The effect of chronic conditions on stated preferences for health. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(4):697–702.

Zarate V, Kind P, Chuang LH. Hispanic valuation of the EQ-5D health states: a social value set for Latin Americans. Value Health. 2008;11(7):1170–7.

Hobbins A, Barry L, Kelleher D, Shah K, Devlin N, Goni JMR, et al. Utility values for health states in Ireland: a value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(11):1345–53.

Wittrup-Jensen KU, Lauridsen J, Gudex C, Pedersen KM. Generation of a Danish TTO value set for EQ-5D health states. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37(5):459–66.

Jensen CE, Sørensen SS, Gudex C, Jensen MB, Pedersen KM, Ehlers LH. The Danish EQ-5D-5L value set: a hybrid model using cTTO and DCE data. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021;19(4):579–91.

Chevalier J, de Pouvourville G. Valuing EQ-5D using time trade-off in France. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(1):57–66.

Greiner W, Claes C, Busschbach JJ, von der Schulenburg JM. Validating the EQ-5D with time trade off for the German population. Eur J Health Econ. 2005;6(2):124–30.

Lamers LM, McDonnell J, Stalmeier PF, Krabbe PF, Busschbach JJ. The Dutch tariff: results and arguments for an effective design for national EQ-5D valuation studies. Health Econ. 2006;15(10):1121–32.

Andrade LF, Ludwig K, Goni JMR, Oppe M, de Pouvourville G. A French value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(4):413–25.

Ludwig K, Graf von der Schulenburg JM, Greiner W. German value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(6):663–74.

Versteegh M, Vermeulen K, Evers S, Ardine de Wit G, Prenger R, Stolk E. Dutch tariff for the five-level version of EQ-5D. Value Health. 2016;19(4):343–52.

Scalone L, Cortesi PA, Ciampichini R, Belisari A, D’Angiolella LS, Cesana G, et al. Italian population-based values of EQ-5D health states. Value Health. 2013;16(5):814–22.

Finch AP, Meregaglia M, Ciani O, Roudijk B, Jommi C. An EQ-5D-5L value set for Italy using videoconferencing interviews and feasibility of a new mode of administration. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292: 114519.

Ferreira PL, Antunes P, Ferreira LN, Pereira LN, Ramos-Goñi JM. A hybrid modelling approach for eliciting health state preferences: the Portuguese EQ-5D-5L value set. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(12):3163–75.

Ramos-Goñi JM, Craig BM, Oppe M, Ramallo-Fariña Y, Pinto-Prades JL, Luo N, et al. Handling data quality issues to estimate the Spanish EQ-5D-5L value set using a hybrid interval regression approach. Value Health. 2018;21(5):596–604.

Rencz F, Brodszky V, Gulácsi L, Golicki D, Ruzsa G, Pickard AS, et al. Parallel valuation of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L by time trade-off in Hungary. Value Health. 2020;23(9):1235–45.

Golicki D, Jakubczyk M, Graczyk K, Niewada M. Valuation of EQ-5D-5L health states in Poland: the first EQ-VT-based study in central and Eastern Europe. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(9):1165–76.

Paveliu MS, Olariu E, Caplescu R, Oluboyede Y, Niculescu-Aron IG, Ernu S, et al. Estimating an EQ-5D-3L value set for Romania using time trade-off. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7415.

Prevolnik Rupel V, Srakar A, Rand K. Valuation of EQ-5D-3l health states in Slovenia: VAS based and TTO based value sets. Zdr Varst. 2020;59(1):8–17.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Lidia Engel for her thorough feedback as a discussant at the 1st EuroQol Early Career Researcher Meeting on 1 March, 2020 in Prague.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant agreement no. 779292.

Conflict of interest

Jan Busschbach is a member of the EuroQol Group. Agata Łaszewska, Ayesha Sajjad, Judit Simon and Leona Hakkaart-van Roijen have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The supra-national value sets were calculated using coefficients from existing valuation studies available in the peer-reviewed articles. The calculated value sets are reported in the study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

JS and LHR conceived the study idea, developed the concept of supra-national value sets, secured funding and supervised the study. AŁ and AS developed the conceptual framework and methods for the study with feedback from JS, AS, LHR and JB. AS, LHR and JB developed methods of supra-national value set calculations. AŁ conducted the literature search and the analysis for the study and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. AS conducted the statistical analyses and estimated supra-national value sets. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Łaszewska, A., Sajjad, A., Busschbach, J. et al. Conceptual Framework for Optimised Proxy Value Set Selection Through Supra-National Value Set Development for the EQ-5D Instruments. PharmacoEconomics 40, 1221–1234 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01194-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01194-y