Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate patients’ inhaler competence and satisfaction with the Easyhaler® dry powder inhaler.

Design

Two open, uncontrolled, non-randomised studies.

Setting

Real life based on patients attending 56 respiratory clinics in Hungary.

Participants

Patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (n = 1016).

Intervention

In a 3-month study, adult patients (age range 18–88 years; n = 797) received twice-daily inhalations of formoterol via Easyhaler®, and in a consequential study (from one visit to another, with 3–12 months in-between) children and adolescents (age range 4–17 years; n = 219) received salbutamol via Easyhaler® as needed.

Main Outcome Measures

Control of six Easyhaler® handling steps and patients’ satisfaction with Easyhaler® based on questionnaires.

Results

Correct performances (minimum and maximum of the six steps) were noticed after one demonstration in 92–98 % of the adults, 87–99 % of the elderly, 81–96 % of the children and 83–99 % of the adolescents. These figures had markedly increased at the last visit. Repeat instructions were necessary in 26 % of the cases. Investigators found Easyhaler® easy to teach in 87 % of the patients and difficult in only 0.5 %. Patients found Easyhaler® easy to learn and use, and the patients’ (and parents’) satisfaction with the inhaler was very high. Lung function values [forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), peak expiratory flow (PEF)] improved statistically significantly during the studies, indicating good inhaler competence and treatment adherence.

Conclusion

Investigators found Easyhaler® easy to teach and patients found it easy to use, and their satisfaction with the device was high.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Inhalation is the preferred route of drug administration for patients with airway diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [1, 2]. Inhalation delivers drugs directly to the airways and thereby the dose can be small compared with oral therapy, and the risk of systemic side effects is reduced. With β2-receptor agonists and anticholinergics, direct delivery to the airways also results in more rapid bronchodilation than oral treatment. Furthermore, with the rapid and long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) formoterol the duration of the bronchodilation is enhanced compared with oral treatment [3]. Several types of devices for delivery of inhaled drugs are available [4].

The effectiveness of inhaled drugs can be influenced by factors such as age, gender, education, duration and severity of disease, type of inhaler used, inhalation technique and many others [5, 6]. It has been shown that differences in effectiveness of inhalers have clinical implications [7]. Meta-analyses, however, indicate that when patients can apply the correct inhalation technique, all inhalers can achieve the same therapeutic effects, although different metered or delivered doses are required [8, 9]. However, despite treatment guidelines [1, 2], control of airway diseases in real life is rather poor [10, 11], inhaler mishandling common, and often associated with reduced disease control [12–14].

Easy and reliable inhalation may improve inhaler competence and adherence to prescribed medications [15, 16]. Although it is apparent that no single inhaler can be ideal for all patients, clinical evaluations have indicated, and experts have expressed the opinion, that the dry powder inhaler Easyhaler® (Orion Corporation, Espoo, Finland) comes very close to an ‘ideal inhaler’ [17]. This includes a consistent fine particle dose across a wide range of inspiratory flow rates [18], high lung deposition [19, 20] and patient preferences [21, 22].

Patient preferences also play an important role when prescribing an inhaler [23]. Several controlled clinical studies have suggested that patient preferences and inhaler competence are good when drugs have been administered via Easyhaler® and that the device is easy to teach, learn and use [22, 24–27]. However, inhaler competence and patient satisfaction with Easyhaler® have not been tested in real-life situations. This information is clearly warranted [16]. In this study we therefore report the results of two real-life studies where Easyhaler® has been used for the delivery of formoterol or salbutamol.

2 Aim of the Studies

The primary aims of the studies were to evaluate the patients’ inhaler competence and their satisfaction with Easyhaler® in real-life settings.

3 Material and Methods

3.1 Study A

This was an open, uncontrolled, non-randomized, 3-month, multicentre study in 46 study centres evaluating the efficacy, safety and patient satisfaction of formoterol Easyhaler® in patients with asthma or COPD requiring treatment with an inhaled long-acting bronchodilator (LABA) according to treatment guidelines. Ethics committee approval was obtained via the Central National Procedure. The study protocol was approved under the code 22606-0/2010-1018EKU (886/PI/10).

3.1.1 Patients

Study subjects were selected from the patient population routinely attending the clinics. Patients aged from 18 years (no upper age limit) could be included. The asthma patients should not have been earlier treated with a LABA, or they should be patients not well controlled on actual therapy without a LABA, or patients who, based on the manufacturer’s instructions, were unable to use their current inhaler(s) in a correct way.

Eligible patients were those requiring add-on treatment with LABA, according to therapeutic guidelines [1]. These included asthmatic patients suffering from persistent, moderate asthma (FEV1 60–80 % of predicted normal values and/or an FEV1 or PEF variability >30 %), severe asthmatic patients (FEV1 corresponding to <60 % of predicted values or PEF variability >30 %), patients with moderate COPD (post-bronchodilator FEV1 ranging from ≥50 to <80 % of predicted normal values) or more severe COPD patients (post-bronchodilator FEV1 <50 %). Patients with known hypersensitivity to formoterol or lactose were excluded.

3.1.2 Medication

The patients—asthma patients as well as patients with COPD—were treated with formoterol Easyhaler® 12 μg twice daily. The asthma patients also used an inhaled corticosteroid as controller therapy according to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines [1]. Patients with COPD always received formoterol Easyhaler® 12 μg twice daily.

3.1.3 Methods

There were three clinic visits in the study. First, a screening visit (visit 1) when demographic data were recorded, including smoking history and type of inhaler device used. At all three visits, pulmonary function testing (FEV1, FVC and PEF) was performed. The lung function measurements were not standardized, neither in terms of use of inhaled β2-agonists before the tests nor in terms of time of the day. Patients were instructed in the use of Easyhaler® and they received a questionnaire to be filled in during the study. The instruction of Easyhaler® contained six handling steps:

-

1.

Take off the blue cap

-

2.

Shake the device in an upright position

-

3.

Push the top of the device until you here a click

-

4.

Exhale, put the mouthpiece into your mouth and inhale deeply

-

5.

Repeat steps 2–4 if more than one dose is prescribed

-

6.

Put the blue cap back on.

The investigator recorded how many times it was necessary to repeat the instructions until the patient could demonstrate the correct use of the device. The investigator also answered the question of how easy it was to teach the patient in the correct use of Easyhaler®.

Visit 2 took place 1 week later (or within 30 days from visit 1), when handling of Easyhaler® was checked and lung function tests were performed. Lung function tests were performed with standard equipment available at the clinics.

Visit 3 took place after 3 months, when handling of Easyhaler® was checked again, lung function tests were performed and the filled-in questionnaire was given back to the investigator.

At all three visits, measurements of heart rate and blood pressure were performed as part of an overall safety evaluation.

3.2 Study B

This was an open, uncontrolled, non-randomized, multicentre study at ten centres evaluating the efficacy, safety and patient satisfaction of salbutamol Easyhaler® used as needed in children and adolescents with any stage of asthma. Results were obtained at the next clinical visit, which usually took place after 3–4 months but always within 1 year from the first visit. Ethics committee approval was obtained via the Central National Procedure. The study protocol was approved under the code 10732-1/2011-EKU (645/PI/11).

3.2.1 Patients

Patients should have been 4–17 years of age and using salbutamol pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI) with a spacer for temporary relief of symptoms or prophylactically to avoid exercise- or allergen-induced bronchoconstriction. Children currently using a β2-agonist pMDI attached to a spacer and who may prefer to use a smaller device could also be included. Patients with known hypersensitivity to salbutamol or lactose were excluded.

3.2.2 Medication

Patients were asked to inhale one 200 μg dose of salbutamol as needed depending on symptoms but not more than four doses per day. Regular maintenance treatment with salbutamol should be avoided.

3.2.3 Methods

There were two clinic visits in the study. First, a screening visit (visit 1) when demographic data and type of inhaler device and spacer used were recorded. Patients were instructed in the use of Easyhaler® (as for Study A). Visit 2 took place within 1 year from visit 1 depending on the asthma stage (intervals 1, 3, 6 or 12 months), when parents and children filled in a questionnaire. At visits 1 and 2, lung function tests were performed (FEV1, FVC and PEF) with standard equipment available at the clinics.

At visit 1, the investigators filled in a questionnaire about teaching of Easyhaler® and how easy it was for patients to learn the correct use.

4 Statistical Analyses

Changes in lung function variables were analysed using a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) and SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) [28]. Each lung function variable (FEV1, FVC and PEF) was modelled separately using MMRM, including age group, visit and age group by visit interaction, as independent variables. Repeated statement was used to specify the repeated measures factor (visit) and the subject variable (subject) identifying observations that are correlated. Differences between visits in lung functions were obtained using the estimate statement in SAS Proc Mixed. Estimates of means of each lung function are least square means from the statistical models.

5 Results

There was a total of 797 patients included in study A and 219 in study B. Demographic data of the study patients is shown in Table 1 divided by age (children, adolescents, adults, elderly) and diagnosis (asthma, COPD). Gender, age, lung function values as predicted normal values and smoking habits are also reported.

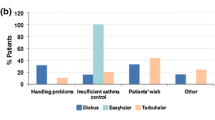

The patients’ previous inhaler use is presented in Table 2.

5.1 Investigators’ Evaluation of Teaching Patients the Use of Easyhaler®

In 92 % of the patients with asthma and 83 % of the patients with COPD the investigators reported that it was easy to teach the correct use of Easyhaler®. Correct use of Easyhaler® was achieved with just one demonstration in 77 % of the asthma patients and 72 % of the patients with COPD. In relation to age, the correct use of Easyhaler® was achieved with one demonstration in 64 % of the children, 76 % of the adolescents, 78 % of the adults and 70 % of the elderly. Teaching was reported to be hard in one child, one adult and three elderly patients. In 13 % of the patients, teaching was considered not easy but not hard, i.e. something in-between.

The development of the correct manoeuvres over time is shown in Table 3 for adults and the elderly (study A) and in Table 4 for children and adolescents (study B). A gradual improvement in the use of Easyhaler® was noted, particularly in children and adolescents whose correct use was not so good at the first training compared with the adults and elderly patients.

5.2 Patients’ Opinion About How Easy it was to Learn the Correct Use of Easyhaler®

Patients’ opinion about how easy it was to learn the correct use of Easyhaler® is shown in Table 5. The vast majority of patients found the use of Easyhaler® very easy or easy to learn. There were no major differences between the age groups, with the exception that fewer elderly patients reported the use of Easyhaler® to be very easy. Compared with their earlier inhalation devices, 88 % of the children, 86 % of the adolescents, 60 % of the adults and 69 % of the elderly found Easyhaler® easier to learn. Only eight patients found Easyhaler® more difficult to learn compared with their previous device. The rest of the patients did not see any difference in the learning procedure.

Of the patients with asthma, 76 % found Easyhaler® easier to use compared with their previous device and 23 % found no difference. Among patients with COPD, the corresponding figures were 62 and 37 %.

5.3 Patients’ Satisfaction with the Use of Easyhaler®

Patients’ satisfaction with the use of Easyhaler® is shown in Table 6. A total of 95 % of the patients were very satisfied (42.7 %) or satisfied (52.7 %) with their use of Easyhaler®. No major differences were seen between the four age groups, although children (and their parents) and adolescents were more often very satisfied compared with the adults and elderly patients.

Patients with asthma were more often very satisfied with Easyhaler® (52.6 %) compared with patients with COPD (33.4 %). The percentages of patients reporting that they were satisfied were 44.4 and 61.1 %, respectively.

5.4 Lung Function with the Use of Easyhaler®

Lung function values at visit 1 (before the use of Easyhaler®) and at the follow-up visits are shown in Fig. 1 for adults and the elderly (study A), and in Fig. 2 for children and adolescents (study B). Clear improvements in lung function were noticed in all patient groups, indicating good inhaler competence and adherence to treatment. The increases in all four age groups and for all three lung function variables (FEV1, FVC and PEF) were statistically highly significant.

6 Discussion

Results of randomized controlled trials may not predict effectiveness of inhaled drugs, and authors have expressed concern about the external validity or generalizability of trial results [29, 30]. Patients included in controlled trials receive adequate inhaler training and have to demonstrate and maintain proper inhaler competence. Moreover, most randomized controlled trials are short-term trials and there is some evidence that, in the real world, inhaler technique deteriorates over time [31] and that may affect clinical outcomes [32, 33]. Thus, results of real-world studies are warranted [16].

In this study we report the results of two multicentre, real-life studies with the use of the dry powder inhaler, Easyhaler®: one with twice-daily inhalations of formoterol in patients with asthma or COPD, and one with as-needed inhalations of salbutamol in children and adolescents with asthma. All together, more than 1000 patients were included and they represent a wide age range, from 3 to 88 years of age. The studies were also of a sufficiently long duration—3 months and up to 1 year, respectively—in order to make reliable user evaluations possible.

In the vast majority of the cases the investigators found Easyhaler® easy to teach, and second or third instructions were necessary in only 26 % of the patients. The instruction to shake the inhaler appeared, for the patients, to be the most difficult manoeuvre to remember. After one instruction a total of 81 % of the children, 83 % of the adolescents, 87 % of the elderly and 92 % of the adults performed all manoeuvres correctly. At the last study visit these figures had increased to a minimum of 93 %. The improved lung function values in all age groups, and both in asthma and COPD patients, also indicate that the inhaler competence remained good, as well as treatment adherence. It has been suggested that the ease of use of an inhaler device may correlate with inhaler competence and thereby with adherence to treatment [14, 15].

The patients reported that it was easy to learn how to use Easyhaler® and they were satisfied or very satisfied with the use of the inhaler.

The high figures for patient satisfaction and patients’ reports on how easy it was to learn the correct use of Easyhaler® may suggest that this device is the most easy to use. That conclusion cannot, however, be drawn as no real comparison has been made.

Our study also has other limitations. Most patients with airway diseases have used inhaler devices previously and have a good idea about inhalation manoeuvres in general. Therefore it would have been more reliable to expose patients not previously using inhalers (or volunteers) to the devices to be evaluated. The majority of patients whose previous inhaler devices were recorded had used a pMDI, which is the most difficult of all inhalers to use correctly [34, 35]. Almost one-fifth of the patients had used multiple devices. Therefore, it is not surprising that more than 50 % of both the asthma and COPD patients found Easyhaler® easier to use than their previous device. For the same reason, most patients reported that they were satisfied or very satisfied with Easyhaler®. For children left to use a pMDI with a spacer (and maybe with a face mask) for temporary relief of symptoms, a change to a less bulky but effective device is also easy to appreciate. A further limitation is that a crossover design was not used. It would have been an advantage to also evaluate and record the manoeuvres with the previous devices or with another dry powder inhaler.

Problems encountered by patients not using inhaler devices correctly have led to the concept of one universal ‘ideal’ inhaler [16, 17]. However, no inhaler is 100 % ideal. The inhalers on the market are ‘Realhalers’, not ‘Idealhalers’ and physicians have to weigh up the pros and cons for each device to make the most appropriate choice [36]. An ‘ideal inhaler’ should be portable, easy to use, ‘nice looking’, inexpensive, loaded with multiple doses, have a dose counter, and show dosing accuracy and consistency over a wide range of inspiratory flows. To avoid hand–mouth dyscoordination, the device should be actuated and driven by the inspiratory flow. It should be suitable for use in both acute and chronic situations, i.e. have a high versatility. Technically, inhalation through the ‘ideal inhaler’ should result in a high lung deposition, thereby reducing the nominal doses to be administered and the risk of local side effects (inhaled corticosteroids) and systemic effects. The variability in lung deposited doses should be minimal. It is well known that pMDIs, compared with dry powder inhalers, live up to only a few of these requirements [37–39]. There are also obvious differences between dry powder inhalers, where the multidose, reservoir-type dry powder inhalers appear to have a clear advantage [7, 37, 39]. Easyhaler®, with its dose consistency over a wide range of inspiratory flows, is an inhaler device that comes very close to being an ‘Idealhaler’ [16, 17, 27].

Bearing in mind the inherent variability among patients, it may be preferable that inhalers should be matched to the patient [16]. The results of our two studies show that Easyhaler® can be matched to a large majority of patients with airway diseases irrespective of age, and that they are satisfied with its use. Easyhaler® could therefore be one component in the strategy by which asthma management can be improved as requested by the Brussels Declaration [40].

7 Conclusion

In patients with asthma or COPD and representing a wide range of ages and disease severities, investigators found Easyhaler® easy to teach and that patients found it easy to use and their satisfaction with the device was high. Lung function improved markedly and significantly during the studies, indicating persistent good inhaler competence and treatment adherence. As a device, Easyhaler® appears to come close to an ‘ideal’ inhaler.

References

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. GINA report. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Bethesda, NIH Publication Number 02-3659. 2012. http://www.ginasthma.com.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. GOLD report. Global strategy for diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. Bethesda, NIH 2009. 2012. http://www.goldcopd.org.

Löfdahl C-G, Svedmyr N. Formoterol fumarate, a new beta 2-adrenoceptor agonist: acute studies on selectivity and duration of effect after inhaled and oral administration. Allergy. 1989;44(4):264–71.

Laube BL, Janssens HM, de Jongh FHC, Devadason SG, Dhand R, Diot P, et al. What the pulmonary specialist should know about the new inhalation therapies. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(6):1308–31.

van der Palen J, Klein JJ, van Herwaarden CLA, Zielhuis GA, Seydel ER. Multiple inhalers confuse asthma patients. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(5):1034–7.

Lavorini F, Magnan A, Dubus JC, Voshaar T, Corbetta L, Broeders M, et al. Effect of incorrect use of dry powder inhalers on management of patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2008;102(4):593–604.

Selroos O, Pietinalho A, Riska H. Delivery devices for inhaled asthma medication: clinical implications of differences in effectiveness. Clin Immunother. 1996;6(4):273–99.

Brocklebank D, Ram F, Wright J, Barry P, Cates C, Davies L, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of inhaler devices in asthma and chronic obstructive airway disease: a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(26):1–149.

Dolovich MB, Ahrens RC, Hess DR, Anderson P, Dhand R, Rau JL, et al. Device selection and outcomes of aerosol therapy: evidence-based guidelines. American College of Chest Physicians/American College of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology. Chest. 2005;127(1):335–71.

Rabe KF, Vermeire PA, Soriano JB, Maier WC. Clinical management of asthma in 1999: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Europe (AIRE) study. Eur Respir J. 2000;16(5):802–27.

Rabe KF, Adachi M, Lai CK, Soriano JB, Vermeire PA, Weiss KB, et al. Worldwide severity and control of asthma in children and adults: the global asthma insights and reality surveys. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(1):40–7.

Lindgren S, Bake B, Larsson S. Clinical consequences of inadequate inhalation technique in asthma therapy. Eur Respir Dis. 1987;70(2):93–8.

Giraud V, Roche N. Misuse of corticosteroid metered-dose inhaler is associated with decreased asthma stability. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(2):246–51.

Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, Cinti C, Lodi M, Martucci P, et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med. 2011;105(6):930–8.

Crompton GK, Barnes PJ, Broeders M, Corrigan C, Corbetta L, Dekhuijzen R, et al. The need to improve inhalation technique in Europe: a report from the Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team. Respir Med. 2006;100(9):1479–94.

Chrystyn H, Haahtela T. Real-life inhalation therapy: inhaler performance and patient education matter. Eur Respir Dis. 2012;8(1):11–8.

Chrystyn H. Closer to an ‘Ideal Inhaler’ with the Easyhaler®. An innovative dry powder inhaler. Clin Drug Investig. 2006;26(4):175–83.

Palander A, Mattila T, Karhu M, Muttonen M. In vitro comparison of three salbutamol-containing multidose dry powder inhalers. Buventol Easyhaler®, Inspiryl Turbuhaler®, and Ventolin Diskus. Clin Drug Investig. 2000;20(1):25–33.

Vidgren M, Silvasti M, Korhonen P, Kinkelin A, Frischer B, Stern K. Clinical equivalence of a novel multiple dose powder inhaler versus a conventional metered dose inhaler on bronchodilating effects of salbutamol. Arzneim.-Forsch./Drug Res. 1995;45(1):44–7.

Newman SP, Pitcairn GR, Adkin DA, Vidgren MT, Silvasti M. Comparison of beclomethasone dipropionate delivery by Easyhaler® dry powder inhaler and pMDI plus large volume spacer. J Aerosol Med. 2001;14(2):217–25.

Ahonen A, Leinonen M, Ranki-Pesonen M. Patient satisfaction with Easyhaler® compared with other inhalation systems in the treatment of asthma: a meta-analysis. Curr Ther Res. 2000;61(2):61–73.

Giner J, Torrejón M, Ramos A, Casan P, Granel C, Plaza V, et al. Patient preference in the choice of dry powder inhalers. Arch Bronchopneumol. 2004;40(3):106–9.

Lenney J, Innes JA, Crompton GK. Inappropriate inhaler use: assessment of use and patient preference of seven inhalation devices. Respir Med. 2000;94(5):496–500.

Jäger L, Laurikainen K, Leinonen M, Silvasti M. Beclomethasone dipropionate Easyhaler® is as effective as budesonide Turbohaler® in the control of asthma and is preferred by patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2000;54(6):368–72.

Schweisfurth H, Malinen A, Koskela T, Toivanen P, Ranki-Pesonen M. Comparison of two budesonide powder inhalers, Easyhaler® and Turbuhaler®, in steroid-naïve asthmatic patients. Respir Med. 2002;96(8):599–606.

Vanto T, Hämäläinen KM, Vahteristo M, Wille S, Njå F, Hyldebrandt N. Comparison of two budesonide dry powder inhalers in the treatment of asthma in children. J Aerosol Med. 2004;17(1):15–24.

Rönmark E, Jögi R, Lindqvist A, Haugen T, Meren M, Loit HM, et al. Correct use of three powder inhalers: comparison between Diskus, Turbuhaler, and Easyhaler. J Asthma. 2005;42(3):173–8.

SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 12.1 user’s guide. Cary: SAS Institute Inc; 2012.

Herland K, Akselsen JP, Skjonsberg OH, Bjermer L. How representative are clinical study patients with asthma or COPD for a larger “real life” population of patients with obstructive lung disease? Respir Med. 2005;99(1):11–9.

Travers J, Marsh S, Williams M, Weatherall M, Caldwell B, Shirtcliffe P, et al. External validity of randomized controlled trials in asthma: to whom do the results of the trials apply? Thorax. 2007;62(3):219–23.

Virchow JC, Crompton GK, Dal Negro R, Pedersen S, Magnan A, Seidenberg J, et al. Importance of inhaler devices in the management of airway disease. Respir Med. 2008;102(1):10–9.

Price D, Thomas M, Mitchell G, Niziol C, Featherstone R. Improvement of asthma control with a breath-actuated pressurised metered dose inhaler (BAI): a prescribing claims study of 5556 patients using a traditional pressurised metered dose inhaler (MDI) or a breath-actuated device. Respir Med. 2003;97(1):12–9.

Price D, Haughney J, Sims E, Ali M, von Ziegenweidt J, Hillyer EV, et al. Effectiveness of inhaler types for real-world asthma management: retrospective observational study using the GPRD. J Asthma Allergy. 2011;4(1):37–47.

Crompton GK. Problems patients have using pressurized aerosol inhalers. Eur J Respir Dis. 1982;63(Suppl 119):101–9.

Hilton S. An audit of inhaler technique among asthma patients of 34 general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40(341):505–6.

Borgström L, Asking L, Thorsson L. Idealhalers or realhalers? A comparison of Diskus and Turbuhaler. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(12):1488–95.

Borgström L, Derom E, Ståhl E, Wåhlin-Boll E, Pauwels R. The inhalation device influences lung deposition and bronchodilating effect of terbutaline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(5):1636–40.

Borgström L, Bengtsson T, Derom E, Pauwels R. Variability in lung deposition of inhaled drug, within and between asthmatic patients, with a pMDI and a dry powder inhaler, Turbuhaler. J Int Pharm. 2000;193(2):227–30.

Borgström L. The importance of the device in asthma therapy. Respir Med. 2001;95(Suppl B):S26–9.

Holgate S, Bisgaard H, Bjermer L, Haahtela T, Haughney J, Horne R, et al. The Brussels Declaration: the need for change in asthma management. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(6):1433–42.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mikko Vahteristo, MSc, at Orion Pharma, Finland, for the statistical analyses, and Semeco AB, Vejbystrand, Sweden, for drafting the manuscript. The studies were sponsored by Orion Pharma, Espoo, Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gálffy, G., Mezei, G., Németh, G. et al. Inhaler Competence and Patient Satisfaction with Easyhaler®: Results of Two Real-Life Multicentre Studies in Asthma and COPD. Drugs R D 13, 215–222 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-013-0027-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-013-0027-3