Abstract

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are major causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Optimal control of these conditions is a constant challenge for both physicians and patients. Poor inhaler practice is widespread and is a substantial contributing factor to the suboptimal clinical control of both conditions. The practicality, dependability, and acceptability of different inhalers influence the overall effectiveness and success of inhalation therapy. In this paper, experts from various European countries (Finland, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Spain, and Sweden) address inhaler selection with special focus on the Easyhaler® device, a high- or medium–high resistance dry-powder inhaler (DPI). The evidence examined indicates that use of the Easyhaler is associated with effective control of asthma or COPD, as shown by the generally accepted indicators of treatment success. Moreover, the Easyhaler is widely accepted by patients, is reported to be easy to learn and teach, and is associated with patient adherence. These advantages help patient education regarding correct inhaler use and the rational selection of drugs and devices. We conclude that switching inhaler device to the Easyhaler may improve asthma and COPD control without causing any additional risks. In an era of climate change, switching from pressurized metered-dose inhalers to DPIs is also a cost-effective way to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases.

Enhanced feature (slides, video, animation) (MP4 43768 kb)

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Success in treating asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may depend on inhaler choice. |

Correct use of the Easyhaler® dry-powder inhaler (DPI) is less dependent on patients’ hand–breath coordination than use of a pressurized metered-dose inhaler (pMDI). |

The Easyhaler delivers medication consistently and reliably at low respiratory rates (≤ 30 l/min) and inhalation volumes (down to 0.5 l), making it suitable for the majority of asthma and COPD patients. |

In clinical studies, patients often express a preference for the Easyhaler over pMDIs and other devices. They report that it is easy to learn and use. |

Switching an inhaler device to the Easyhaler may improve asthma and COPD control and can be done safely. Preferring DPIs to pMDIs is also a cost-effective way to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a video abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16578746.

Introduction

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are widespread illnesses that impose significant morbidity and mortality burdens in countries around the world. COPD is in fact one of the top five causes of death worldwide [1, 2]. Both conditions also exert substantial socioeconomic impacts through their effects on productivity and erosion of quality of life [3]. Although an elaborate array of pharmacologic treatments is available and widely recommended in expert guidelines, both asthma and COPD remain uncontrolled in a substantial proportion of patients [4, 5] and one factor contributing to this situation is suboptimal adherence to treatment.

Given that many therapies for asthma and COPD are delivered by inhalation, incorrect and/or inconsistent inhaler use may have a substantial influence on treatment efficacy. Poor inhaler practice is widespread in the treatment of asthma and COPD and reports on this matter may even under-represent the true situation since many patients’ suboptimal technique may go unidentified for lengthy periods of time. This phenomenon has been apparent since the introduction of inhalers, with little evidence of any sustained improvement over time [6].

As recently articulated by Kaplan and van Boven [7] in the principles of the UR-RADAR concept, the selection and switching of inhalers should be considered within a wider framework of clinical evaluation and patient engagement. Notwithstanding acknowledged differences between different devices with regard to release mechanism, drug particle size and deposition, and required inspiratory flow, the optimal matching of patient and inhaler can exert a powerful influence on the overall clinical success of a treatment strategy in these chronic respiratory diseases [8,9,10,11,12]. Similarly, switching requires careful consideration and is not a process to be undertaken without patient consent and retraining in the correct use of a novel device.

In this paper, experts from various European countries (Finland, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Spain, and Sweden) address some of the issues involved in inhaler selection and device switching with special focus on the Easyhaler® dry powder inhaler (DPI).

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain details of any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Technical and Theoretical Aspects of Inhaler Devices

A brief consideration of the relative advantages of different types of inhaler is appropriate. A full treatment of the options is beyond the scope of this short review, which focuses on pressurized metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs) and dry-powder inhalers (DPIs), the latter being specifically exemplified by the Easyhaler (for a concise technical review of the Easyhaler device, the reader is referred to a recent overview [13]). Kaplan and van Boven [7] have published a tabulated comparison of other device types, including the breath-actuated metered-dose inhaler and soft-mist inhaler and nebulizer, while complementary comparative data on issues such as fine-particle dose have been reviewed at length by Lavorini et al. [14].

pMDIs are the longest-established inhaler type for asthma and COPD treatment and remain the most widely utilized. These devices utilize a pressurized propellant to deliver a metered dose of drug as an aerosol. Use of propellant means that only a low inspiratory effort is required by the patient although the inspiration needs to be slow and prolonged. Despite this, pMDIs can be difficult to use successfully, as they require a high level of hand–breath coordination to ensure inhalation of the delivered dose (except for extra-fine-particle pMDIs, which do not require strict coordination). Users often struggle with device activation timing, as was illustrated in the CRITIKAL trial, which identified actuation before inhalation in 24.9% of patients and associated that wrong practice with uncontrolled asthma (odds ratio [OR] 1.55, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.11–2.16) [15]. In some cases, due to the hand–breath coordination challenge, patients are prescribed, or advised to use, an additional spacer device for administration of the drug, which represents an additional source of user-generated errors or at least an additional inconvenience such as reduced portability of the pMDI, the need to wash the spacer regularly (although not in the case of extra-fine-particle pMDIs) and, last but not least, an extra cost [16].

Is the Easyhaler Different?

In contrast to pMDIs, the drug dose of DPIs such as Easyhaler is released by force generated by the patient’s inhalation (Fig. 1). The requirement of coordination—and the clinical consequences of poor coordination—is mitigated. During each inhalation, a turbulent airflow is created inside the DPI by the interaction between the patient’s inhalation maneuver and the resistance inside the device. The kinetic energy of the turbulent airflow breaks up the drug powder and separates/de-aggregates the drug particles from the carrier particles (usually lactose). For this reason, high- or medium–high-resistance DPIs are poised to provide a more favorable set of inhalation characteristics for drug de-aggregation and delivery of the inhaled dose into the lungs than lower-resistance DPIs [17].

The Easyhaler device (on the left). (1) During an inhalation, air enters the device through a small vent and encounter high resistance due to the small size of the opening; (2) High resistance generates a turbulent air flow to the dosing cup; (3) Turbulent air flow ensures de-aggregation of the drug particles and high-dose emission even with low inhalation flows. On the right, the six drugs available with the Easyhaler device are shown

A corollary of this phenomena is that inhalation sufficiently forceful to de-aggregate the powdered drug into breathable-sized particles (European Pharmaceutical limit of the aerodynamic diameter < 5 μm ca.) is required to guarantee drug delivery distal to the oropharynx to deposit at the airways of the lungs. Compared with pMDIs, DPIs require fast and strong inhalation.

Prima facie, this would seem to be a limitation of DPIs for younger asthmatic patients or for COPD patients, at least some of whom have reduced inspiratory force. In clinical practice, however, good drug delivery via the Easyhaler DPI has been demonstrated in a series of studies in asthmatic children and adults with COPD at peak inspiratory flow rates (PIFRs) as low as 28 l/min, a threshold level attainable by the majority of patients with both conditions [18,19,20,21]. In a recent randomized, open-label, crossover study [22] in 100 patients with COPD and 100 healthy volunteers, it was shown that the Easyhaler was preferred by 51% of patients, while 25% favored the comparator (HandiHaler®).

In comparison to the other DPIs (e.g., Turbuhaler®), a greater consistency of drug dose delivery has been recorded with the Easyhaler across a wide range of PIFRs (Fig. 2). The variability in dose delivery with the Easyhaler was significantly smaller than that with Turbuhaler (p < 0.001) and Diskus® (p < 0.001) [23].

Consistency of doses delivered by the Easyhaler, Diskus, and Turbuhaler according to peak inspiratory flow rate. Redrawn after Chrystyn [43]

Clinical Effectiveness at Low Inspiration Rates

The ability of the Easyhaler to deliver clinically relevant improvements in spirometry indices in patients with relatively low inspiration rates was also demonstrated in a double-blind, randomized, cross-over study in 21 pediatric or adult patients with asthma who were switched between the Easyhaler or a pMDI-plus-spacer arrangement. The active therapeutic compound in each case was salbutamol (dose of 100 μg) [24]. The average PIFR through the Easyhaler was 28.7 l/min. Before and after Easyhaler use, peak forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) was 2.44 ± 0.90 and 2.69 ± 0.93 l, respectively, compared with 2.43 ± 0.90 and 2.67 ± 0.97 l, respectively, after administration of salbutamol via pMDI-plus-spacer. Both post-treatment values were significantly larger than the respective pre-treatment values (p < 0.05), with no significant difference between groups up to 60 min after inhalation. Similarly, Malmstrom et al. [17] reported during development of the Easyhaler that the clinical bronchodilator effect of gain of salbutamol (200 μg) delivered via this DPI was equivalent to that from an un-primed MDI with a spacer in children with asthma, including a subset of 15 patients with bronchial obstruction (defined as peak expiratory flow < 85% of predicted).

Clinical Effectiveness at Low Inspiration Volumes

The inhalation volume required for complete dose delivery is also an important consideration because a low inhalation volume may reduce the delivered dose of medication. In vitro assessments indicated that the delivered dose of budesonide/formoterol provided via the Easyhaler was independent of inhalation volume down to 0.5 l, although the formoterol component was decreased by 10% (p < 0.0125) at 0.25 l when a low-dose combination was tested. Delivered dose declined more markedly, and at higher inhalation volumes, for some other DPIs evaluated in this way. These data are particularly relevant to the management of COPD patients, who often have low (< 1 l) inhalation volumes, and provide some assurance that drug delivery from the Easyhaler is likely to be as predicted and sufficient in a large percentage of cases [14].

Robust Practical Performance

In a very recently reported non-comparative in vitro assessment of the salmeterol–fluticasone propionate Easyhaler (50/250 or 50/500 μg per dose) [25], performance, as quantified by the delivered drug dose (DD) and fine-particle dose, remained consistent throughout the lifespan of the inhaler (60 doses) and was unaffected by simulated environmental stress. Drug delivery remained unchanged with or without dropping (DD ranging from 99 to 104% for salmeterol and from 95 to 103% for fluticasone, when setting the initial dose values to 100%), vibration (DD after test: 100–102% and 97–100% for salmeterol and fluticasone, respectively), exposure to moisture (DD after test: 98–102% and 98–107% for salmeterol and fluticasone, respectively) and freeze–thawing (DD after test: 100–101% and 99–101% for salmeterol and fluticasone, respectively). Moreover, no inhaler breakages occurred during these tests, confirming the robustness of the device.

A Wider View on Values: Sustainability

Healthcare is one of the major contributors to emissions of greenhouse gases, and climate breakdown threatens to undo many of the advances in public health achieved over the last 50 years. Therefore, efforts to reach net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases from healthcare are vital [26]. The carbon footprint of inhaled treatments has come under scrutiny recently, largely due to the greenhouse-gas effect of hydrofluoroalkane propellants used in MDIs [27]. These propellants are powerful greenhouse gases (from 1500 to 3000 times greater global warming potential than CO2 [28]), and so have a disproportionate impact on the carbon footprint of treatment. In the UK for instance, MDIs contribute 13% of the core carbon footprint of the National Health Service (NHS) related to delivery of care, and 3% of the “carbon footprint plus” emissions which the NHS can influence [29].

Switching to low-carbon inhalers, such as DPIs, has been identified as a key strategy for the NHS to achieve net zero carbon emissions. Life-cycle analysis of the Easyhaler shows it to have a carbon footprint of 0.58 kg CO2 equivalent per device, a burden much smaller than that of MDIs, which ranges from 9 to 37 kg CO2 equivalent per device [30, 31]. Where clinically appropriate, switching to DPI devices such as the Easyhaler has been proposed as a cost-effective way to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases from MDIs [32].

Clinical Observations and Real-World Experience

Some of the issues involved in inhaler selection and device switching—with special focus on the Easyhaler device—were addressed in a series of recent clinical trials (see Table 1 for a synopsis).

Tamási, Szilasi, and Gálffy [33] have recently presented ‘real-world’ data on the effectiveness of the budesonide/formoterol drug combination in the management of asthma or COPD when administered via Easyhaler. In the same study, use of the Easyhaler was associated with high levels of patient satisfaction. These insights emerged from a multicenter, open-label, non-randomized, non-interventional study conducted at 200 centers in Hungary and involving a total of 1498 adult patients (average age > 50 years; asthma: n = 621; COPD: n = 778; asthma–COPD overlap: n = 99), of whom 455 (30.4%) were newly diagnosed, inhaler-naïve patients and 1043 (69.6%) were switching from other inhalers (Turbuhaler or Diskus DPIs, or pMDIs). The medications administered in the study were budesonide (160 or 320 μg per inhalation) or formoterol (4.5 or 9 μg per inhalation, respectively), with a dose depending on the frequency of administration of medications at baseline.

Most of the enrolled patients (n = 1043) had poorly controlled asthma or experienced a high impact of COPD on their daily lives and were using a maintenance medication at baseline. Treatment effectiveness was assessed after 12 weeks of treatment using spirometry and a range of established condition-appropriate tests. Patient satisfaction with the Easyhaler (on a six-point scale) and physicians’ assessments of ease of use and time taken to learn the DPI technique were also assessed.

Impact on Clinical Respiratory Indices

Significant improvements in lung function, disease control, and health-related quality of life measures (p ≤ 0.01 for all) were reported after 12 weeks of Easyhaler use among both inhaler-naïve patients and those who switched from other devices. By that time, 73.2% of all patients with asthma (asthma and asthma–COPD overlap) were described as ‘well controlled’ in the conclusion of the study. Among patients with asthma, use of reliever inhaler decreased markedly, with 87.2% of patients reporting at week 12 that they used the reliever no more than once a week, compared with 32.2% of patients at baseline. Among patients with COPD, the average COPD Assessment Test score declined from 24.2 ± 5.7 at baseline to 18.2 ± 5.1 at the end of the study (p < 0.001) [33].

High Patient Satisfaction with the Easyhaler

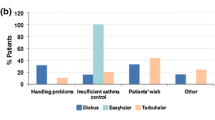

Among the switching patients, 97.2% self-reported very high satisfaction with the Easyhaler (score of one on the six-point scale), compared with < 20% for pre-study devices (Fig. 3). In addition, > 90% of physicians categorized the Easyhaler as very easy (57.7%) or easy (35.3%) to teach, with a similar proportion reporting a teaching time of ≤ 10 min [33].

Patients’ satisfaction after inhaler switch to Bufomix Easyhaler as shown in a study evaluating a total of 1498 patients with obstructive airway disease (asthma: n = 621; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: n = 778; asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap: n = 99), of whom 455 (30.4%) were newly diagnosed inhaler-naïve patients and 1043 (69.6%) were switching from other inhalers. The Bufomix Easyhaler was considered easy to use, and most patients were satisfied with the inhaler after the switch. Comparisons with the metered-dose inhaler (MDI), Diskus/Accuhaler, and Turbuhaler are shown. Redrawn after Tamási et al. [33]

A supplementary analysis in which 961 asthma or COPD patients were stratified according to the inhaler device used at baseline confirmed the general findings of this investigation [34]. Specifically, this analysis documented significant improvements in multiple dimensions of patients’ clinical status in both asthma and COPD patients after switching to Easyhaler-delivered medications (Fig. 4).

Effect of switching to budesonide/formoterol fumarate Easyhaler combination therapy disease control in patients with asthma (n = 398) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; n = 563). P < 0.0001 for comparison of visit 1 versus visit 3. ACT Asthma Control Test, CAT COPD Assessment Test. Redrawn after Gálffy et al. [34]

Notable features of this study were that (a) patients whose proficiency with usage of their previously prescribed inhaler was considered unsatisfactory, or who did not feel comfortable with their device, were eligible to participate and (b) training in use of the Easyhaler was to the standard likely to be encountered in routine care rather than the more intensive levels demanded by a randomized, controlled trial.

The findings favoring the Easyhaler may therefore have a degree of pragmatic resilience. On the other hand, part of the positive reception of the Easyhaler may have been due to the patients’ dissatisfaction with their previous inhaler(s). No information was available on baseline education on inhaler training or adherence data for the pre-study devices. Patients’ perceptions of the Easyhaler may therefore have been inflated by prior poor practice or experiences. The lack of a parallel comparator arm is a further limitation, as is the relatively short duration of the study. Longer investigations would need to be established if the initial gains are durable. Gálffy et al. [34] also noted the desirability of further investigation into possible country-specific differences in patient demographics and/or healthcare systems which may influence inhaler usage and/or switching practice.

Additional Clinical Study Findings

Data from other countries are, nevertheless, reassuring regarding the general utility and affirmative impact of Easyhaler use on clinical status in asthma and COPD.

A very recent report from the SUNNY study in Germany and Sweden (NCT03755544) [35] has substantially corroborated the experience of the Hungarian research already described, documenting improved clinical status and high levels of patient adherence and preference for a salmeterol–fluticasone regimen delivered by the Easyhaler than by alternative devices in a mixed asthma/COPD population of 231 patients treated for 12 weeks.

Similarly, in the UK, an appraisal of 1958 asthma patients treated in primary care concluded that “Typical asthma patients may be switched from other inhaled corticosteroid devices to the Easyhaler with no reduction in clinical effectiveness or increase in cost.” [36].

In a non-randomized, open-label, post-authorization efficacy study in Poland conducted among 2200 adult (mean age, 49.8 ± 17.9 years) outpatients with asthma, delivery of budesonide/formoterol fumarate via an Easyhaler for 8–12 weeks was associated with an increase in the proportion of patients with well-controlled asthma or total control of asthma (Asthma Control Test [ACT] score 20–25 points) from 46.6 to 90.8% (p < 0.001), and with a marked reduction in the proportion of patients with poor control of asthma (ACT score < 15 points) from 14.9 to 1.2% (p < 0.001) [29]. Patient satisfaction with the Easyhaler increased progressively during the study, as assessed by multiple metrics, including ease of preparation for use, maintenance, incorporation of Easyhaler use into the activities of daily living and the overall physical acceptability of the device (size, weight, portability, etc.) [37].

Pediatric Clinical Trial Data

A multicenter, randomized, controlled study conducted at seven hospitals in Thailand to compare the efficacy of salbutamol administered via an Easyhaler, a pMDI with volumatic spacer, or nebulization in mild-to-moderate asthma exacerbations in children aged 5–18 years who presented at an emergency or outpatient department identified no statistically significant differences in the clinical response (assessed using the modified Wood’s asthma score), but less tachycardia among children assigned to the Easyhaler [38].

Mixed Outcomes in COPD

To be set against these reports are the findings of Wittbrodt and colleagues [39], who examined (retrospectively) outcomes among ≈ 3000 adult (≥ 40 years old) COPD patients who were using an inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist delivered via either pMDI (n = 1960) or DPI (n = 1086) and who had been hospitalized with a diagnosis of COPD exacerbation. pMDI patients were significantly more likely to be prescribed a short-acting β-agonist, experienced more COPD exacerbation-related hospital days and had a greater number of pulmonologist visits compared with DPI patients (p < 0.05 for all), findings prima facie suggestive of greater disease severity. However, multivariate analysis revealed that pMDI patients had a decreased likelihood of a COPD exacerbation-related hospital readmission relative to DPI users and incurred significantly lower all-cause and COPD-related healthcare costs (p < 0.05 for both).

On the other hand, in a recent study, almost all (> 99%) studied patients with asthma or COPD, regardless of age or disease severity, were able to achieve the PIFR of ≥ 30 l/min required for efficient dose delivery through the Easyhaler [40].

Our point in introducing these data is to emphasize that evaluation of inhaler-delivered medications is an uncommonly broad and heterogenous area of medical research characterized by widely varying terminology and criteria: findings vary accordingly and a result to support most points of view can be found if one is prepared to scan the literature in sufficient breadth (see Lavorini et al. [14] for an extensive enumeration and discussion of the clinical dataset). This limitation does not negate any one set of findings, but it recognizes the complexities of the field.

Discussion

The sheer range of inhaler devices and the constant enlargement of that range militate against comprehensive head-to-head comparisons of all possible permutations of drug and device [41]. Some element of judgement and approximation is therefore needed when trying to reach pragmatic conclusions about these matters.

Our own view, shaped by personal experience as well as assessment of the relevant published reports, is that the Easyhaler, as a specific DPI, delivers results that are clinically equivalent or non-inferior to those of pMDIs for the administration of corticosteroid/beta-agonist combination therapy when assessed by lung function criteria. Whether lung function criteria should be the central metric of treatment success, especially in COPD, is beyond the scope of this work but well-founded arguments for other indices have been advanced [42].

We further believe, however, that the value of the Easyhaler lies as much in its practical appeal to patients as in its effects on lung function. A checklist of six criteria for an ‘ideal’ inhaler device has been proposed [43] and it may be said at once that no currently available device meets all the stipulated criteria of effectiveness and reproducibility of drug delivery, precision, stability, comfort, versatility (i.e., allowing the administration of different drugs) and environmental considerations (i.e., absence of chemical contaminants and sustainability).

Interestingly, Ahonen et al. [44] performed a meta-analysis of data from nine clinical trials in asthma (n = 802) and reported that the Easyhaler substantially and significantly (p ≤ 0.01) outperformed both alternative DPI devices or pMDIs on all five nominated indices of device acceptability: ease of use, ease of learning how to use, ease of dosing the drug, ease of inhaling, and overall preference.

Further insights may emerge from an ongoing retrospective, multicenter, non-interventional, observational study (Bufoswitch—NTC04663386). This study enrolls patients with asthma and/or COPD to explore how the authorization of at-pharmacy switching to DPIs containing budesonide–formoterol from June 2018 has affected various aspects of asthma control in Norway.

The focus on pharmacist training in BufoSwitch is a timely reminder that asthma and COPD represent an area of medicine where, to a greater than normal extent, the success of a course of therapy is—quite literally—in the hands of patients. The importance of patient education in optimizing the delivery of inhaled medication has recently been reaffirmed in a prospective cohort study of nurse-based education in COPD patients in South Korea [45]. A similar message was delivered, through different conclusions, by the CRITIKAL study (n = 3660) [15], in which critical errors in the use of different types of inhaler were associated with poor clinical outcomes.

An exposition of device-specific and device-critical errors for a very wide range of inhalers can be found in the article by Lavorini et al. [14]. Device-critical errors associated with the Easyhaler include failure to shake the device before use, which may reduce the delivered dose of drug, and failure to hold the device upright when priming.

Patient Education and Patient Preference

Patient preference for a device is also an important consideration and in this context we note two recently completed studies from Spain which used the ‘Feeling of Satisfaction with Inhaler’ (FSI-10) questionnaire to compare asthma patients’ perceptions of the Easyhaler with those of other DPI inhalers or other types of inhaler and which found in each case that patients were more likely to be satisfied with the Easyhaler than with comparator devices [46]. These preferences were apparent in individual domains of the FSI-10, including learning how to use the inhaler, its preparation, its actual use, its weight and size, and its portability [47, 48]. In parallel research in Spain, the cross-sectional, multicenter, observational EFIMIRA study in 1682 asthma patients identified inhaler critical errors in an aggregate of 17% of patients but a significantly lower rate of critical use errors with the Easyhaler than with other devices (10.3 vs. 18.4%; p < 0.05). A smaller percentage of patients using the Easyhaler needed technique adjustment compared with comparator devices (34.4 vs. 51.5–68.8%). Critical errors of inhaler use related strongly to poor asthma control (OR 3.03, 95% CI 2.18–4.21) (Fig. 5) [49].

Critical mistakes with inhaler technique in a cross-sectional, multicenter observational study including asthma patients referred from primary to specialist care for the first time. Significantly fewer critical mistakes were recorded among Easyhaler users versus other dry-powder inhaler users (10.3 vs. 18.4%; p < 0.05). Redrawn after Ribó et al. [49]

It is clear from all of these lines of evidence that patient education regarding how to store and use their devices correctly should have high priority. Success in this area requires that whoever is responsible for patient education is themselves well versed in the features and limitations of the relevant devices. The Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team (ADMIT) have provided one useful starting point for this by identifying ten widespread misconceptions about inhaler-based drug delivery [50]. One point identified by ADMIT that we strongly endorse is that, whenever possible, it is reasonable and desirable to restrict regular inhaled medication to a single type of device. The Easyhaler offers six different drugs or drug combinations in several strengths (see Fig. 1). Minimizing the volume of (sometimes contradictory) information and practices that patients have to master and recall can only have a positive influence on adherence and compliance. Simplicity of use extends to the number of daily doses to be delivered, which should be kept to the minimum necessary for optimal therapeutic effect.

Assessment of the patient’s overall status, including age, peak inspiratory flow inhalation volume, and the presence of cognitive or physical limitations, can shape the choice of the most appropriate type of device. From that starting point, the devices within that class may be assessed in more detail. As already noted, all devices are associated with particular usage errors; the relative importance of these will vary between patients and will help to shape choice.

Initial patient education is probably best done face to face, although the particular circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic may require at least temporary alternative measures and may lead to longer-term changes in the way training is delivered. Certainly, the potential of online videos and similar material as ways of refreshing patient knowledge and proficiency has been highlighted by the impact of COVID-19 and we anticipate further developments in this area and in the associated area of digital monitoring and the management of device errors; some of these health initiatives may currently be speculative but a long-term trend towards such methods seems inevitable. Pending the widespread adoption of such methods, refresher and reminder courses, however delivered, are essential to ensure that patient best practice is encouraged and adhered to.

Conclusions

All in all, the available data support the assumption that the Easyhaler presents benefits which include consistency of dose [43], achievement of optimal PIFR [51], few critical errors in use [49], and overall high patient satisfaction [33, 37]. Moreover, reduction in emissions of greenhouse gases was shown compared to MDIs. At the same time, it appears from the literature that switching devices to the Easyhaler may improve asthma/COPD control and can be done without any additional risks.

Limitations and Knowledge Gaps

When a patient is suffering from uncontrolled asthma or COPD, multiple underlying issues may give rise to the decision to switch inhalers. These include adherence issues, poor inhaler technique, patients’ health, adverse events, patient preferences, and cost considerations.

The common understanding is that switching devices should not be advocated for patients unless they suffer from uncontrolled asthma or COPD, and that this change requires a careful process including patient consent, clinical assessment, patient discussion, device retraining, and follow-up [7]. However, at a population level, there is evidence that switching to ‘an equivalent’ inhaler in patients with COPD and asthma does not negatively affect patients’ health or healthcare utilization. Indeed, disease control seems to improve, perhaps due to an increased awareness of inhalers, which improves compliance [52].

There are, however, inherent difficulties with systematic clinical trials of inhaler switching due to difficulties in blinding, the need for re-education, balancing of arms with regard to inspiratory force, and patients’ personal abilities and preferences [7]. The various studies summarized in Table 1 identify the Easyhaler as a credible option when a switch of drug-delivery device is mooted, but it has to be acknowledged that this is an area of respiratory medicine in which well-configured randomized trials are lacking and that many of those that have been conducted (e.g., Syk et al. [53]) quantify success in terms of disease symptom control. While that is a legitimate outcome, it reveals little direct insight into the relative acceptability of devices for patients or about the factors that shape patients’ perceptions of a given device as being more or less acceptable than comparators. The influence of the circumstances of switching for non-medical reasons (e.g., withdrawal of specific drugs or drug combinations or mandatory/discretionary branded to generic substitutions) can also further complicate appraisal of relative device acceptability.

References

World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2015. https://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/en/ [Last accessed Jul 10, 2021].

GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:585–96.

Brakema EA, Tabyshova A, Van Der Kleij RMJJ, et al. The socioeconomic burden of chronic lung disease in low-resource settings across the globe—an observational fresh air study. Respir Res. 2019;20:291.

Miravitlles M, Sliwinski P, Rhee CK, et al. Predictive value of control of COPD for risk of exacerbations: an international, prospective study. Respirology. 2020;25:1136–43.

Price D, Fletcher M, Van Der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8000 European patients: the recognise asthma and link to symptoms and experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14009.

Sanchis J, Gich I, Pedersen S, Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team (ADMIT). Systematic review of errors in inhaler use: Has patient technique improved over time? Chest. 2016;150:394–406.

Kaplan A, van Boven JFM. Switching inhalers: a practical approach to keep on UR RADAR. Pulm Ther. 2020;6:381–92.

Mäkelä MJ, Backer V, Hedegaard M, et al. Adherence to inhaled therapies, health outcomes and costs in patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107:1481–90.

Molimard M, Raherison C, Lignot S, Depont F, Abouelfath A, Moore N. Assessment of handling of inhaler devices in real life: an observational study in 3811 patients in primary care. J Aerosol Med. 2003;16:249–54.

Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med. 2011;105:930–8.

Gregoriano C, Dieterle T, Breitenstein AL, et al. Use and inhalation technique of inhaled medication in patients with asthma and COPD: Data from a randomized controlled trial. Respir Res. 2018;19:237.

Usmani OS, Lavorini F, Marshall J, et al. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir Res. 2018;19:10.

Lavorini F. Easyhaler®: an overview of an inhaler device for day-to-day use in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Drugs Context. 2019;8: 212596.

Lavorini F, Janson C, Braido F, Stratelis G, Løkke A. What to consider before prescribing inhaled medications: a pragmatic approach for evaluating the current inhaler landscape. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2019;13:1753466619884532.

Price DB, Román-Rodríguez M, McQueen RB, et al. Inhaler errors in the CRITIKAL study: type, frequency, and association with asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1071-81.e9.

Farkas A, Horváth A, Kerekes A, et al. Effect of delayed pMDI actuation on the lung deposition of a fixed-dose combination aerosol drug. Int J Pharm. 2018;547:480–8.

Malmström K, Sorva R, Silvasti M. Application and efficacy of the multi-dose powder inhaler, Easyhaler, in children with asthma. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1999;10:66–70.

Ghosh S, Ohar JA, Drummond MB. Peak inspiratory flow rate in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: implications for dry powder inhalers. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2017;30:381–7.

Malmberg P, Rytilä P, Happonen P, Haahtela T. Inspiratory flows through dry powder inhaler in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: age and gender rather than severity matters. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:257–62.

Malmberg LP, Everard ML, Haikarainen J, Lähelmä S. Evaluation of in vitro and in vivo flow rate dependency of budesonide/formoterol Easyhaler. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2014;27:329–40.

Azouz W, Chetcuti P, Hosker HS, Saralaya D, Stephenson J, Chrystyn H. The inhalation characteristics of patients when they use different dry powder inhalers. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2015;28:35–42.

Jõgi R, Mattila L, Vahteristo M, et al. Inspiratory flow parameters through dry powder inhalers in healthy volunteers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): device resistance does not limit use in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:1193–201.

Palander A, Mattila T, Karhu M, Muttonen E. In vitro comparison of three salbutamol-containing multidose dry powder inhalers: Buventol Easyhaler®, Inspiryl Turbuhaler® and Ventoline Diskus®. Clin Drug Invest. 2000;20:25–33.

Koskela T, Malmström K, Sairanen U, Peltola S, Keski-Karhu J, Silvasti M. Efficacy of salbutamol via Easyhaler unaffected by low inspiratory flow. Respir Med. 2000;94:1229–33.

Turpeinen A, Eriksson P, Happonen A, Husman-Piirainen J, Haikarainen J. Consistent dosing through the salmeterol-fluticasone propionate Easyhaler for the management of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: robustness analysis across the Easyhaler lifetime. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2021;34:189–96.

Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, et al. The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. Lancet. 2019;394:1836–78.

National Health Service (NHS) England. Delivering a “net zero” National Health Service. London, UK: NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2020/10/delivering-a-net-zero-national-health-service.pdf [Last accessed Jul 10, 2021].

Starup-Hansen J, Dunne H, Sadler J, Jones A, Okorie M. Climate change in healthcare: exploring the potential role of inhaler prescribing. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2020;8: e00675.

Tennison I, Roschnik S, Ashby B, et al. Health care’s response to climate change: a carbon footprint assessment of the NHS in England. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5:e84–92.

Orion Pharma. Carbon life cycle assessment report for Orion corporation: executive summary. 2020. Available from: https://www.orion.fi/globalassets/documents/orion-group/sustainability/2020-orion-pharma-product-footprint-exec-summary.pdf [Last accessed Jan 2021].

Wilkinson AJK, Anderson G. Sustainability in inhaled drug delivery. Pharm Med. 2020;34:191–9.

Wilkinson AJK, Braggins R, Steinbach I, Smith J. Costs of switching to low global warming potential inhalers. An economic and carbon footprint analysis of NHS prescription data in England. BMJ Open. 2019;9: e028763.

Tamási L, Szilasi M, Gálffy G. Clinical effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol fumarate Easyhaler® for patients with poorly controlled obstructive airway disease: a real-world study of patient-reported outcomes. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1140–52.

Gálffy G, Szilasi M, Tamási L. Effectiveness and patient satisfaction with budesonide/formoterol Easyhaler® among patients with asthma or COPD switching from previous treatment: a real-world study of patient-reported outcomes. Pulm Ther. 2019;5:165–77.

Henning R, Vinge I, Syk J, et al. Prospektive, offene, multizentrische, nicht interventionelle Studie bei erwachsenen Patienten mit Asthma oder COPD zur Erhebung der klinischen Wirksamkeit des Salmeterol/Fluticason Easyhalers in der täglichen Praxis. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Innere Medizin 2021 [German.]

Price D, Thomas V, von Ziegenweidt J, Gould S, Hutton C, King C. Switching patients from other inhaled corticosteroid devices to the Easyhaler(®): historical, matched-cohort study of real-life asthma patients. J Asthma Allergy. 2014;7:31–51.

Pirożyński M, Hantulik P, Almgren-Rachtan A, Chudek J. Evaluation of the efficiency of single-inhaler combination therapy with budesonide/formoterol fumarate in patients with bronchial asthma in daily clinical practice. Adv Ther. 2017;34:2648–60.

Direkwatanachai C, Teeratakulpisarn J, Suntornlohanakul S, et al. Comparison of salbutamol efficacy in children–via the metered-dose inhaler (MDI) with Volumatic spacer and via the dry powder inhaler, Easyhaler, with the nebulizer–in mild to moderate asthma exacerbation: a multicenter, randomized study. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2011;29:25–33.

Wittbrodt ET, Millette LA, Evans KA, Bonafede M, Tkacz J, Ferguson GT. Differences in health care outcomes between postdischarge COPD patients treated with inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist via dry-powder inhalers and pressurized metered-dose inhalers. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;14:101–14.

Malmberg LP, Pelkonen AS, Vartiainen V, Vahteristo M, Lähelmä S, Jõgi R. Patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can generate sufficient inspiratory flows via Easyhaler (R) dry powder inhaler: a pooled analysis of two randomized controlled trials. J Thor Dis. 2021;13:621–31.

Mannan H, Foo SW, Cochrane B. Does device matter for inhaled therapies in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparative trial of two devices. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:94.

Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:557–82.

Chrystyn H. Closer to an ‘ideal inhaler’ with the Easyhaler: an innovative dry powder inhaler. Clin Drug Investig. 2006;26:175–83.

Ahonen A, Leinonen M, Ranki-Pesonen M. Patient satisfaction with Easyhaler® compared with other inhalation systems in the treatment of asthma: a meta-analysis. Curr Ther Res. 2000;61:61–73.

Ahn JH, Chung JH, Shin KC, et al. The effects of repeated inhaler device handling education in COPD patients: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19676.

Small M, Anderson P, Vickers A, Kay S, Fermer S. Importance of inhaler-device satisfaction in asthma treatment: real-world observations of physician-observed compliance and clinical/patient-reported outcomes. Adv Ther. 2011;28:202–12.

Alvarez-Gutiérrez FJ, Gómez-Bastero Fernández A, Medina Gallardo JF, Campo Sien C, Rytilä P, Delgado RJ. Preference for Easyhaler® over previous dry powder inhalers in asthma patients: results of the DPI PREFER observational study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:349–58.

Valero A, Ribó P, Maíz L, et al. Asthma patient satisfaction with different dry powder inhalers. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2019;13:133–8.

Ribó P, Molina J, Calle M, et al. Prevalence of modifiable factors limiting treatment efficacy of poorly controlled asthma patients: EFIMERA observational study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2020;30:33.

Levy ML, Dekhuijzen PN, Barnes PJ, et al. Inhaler technique: facts and fantasies. A view from the Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team (ADMIT). NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2016;26:16017.

Haughney J, Lee AJ, McKnight E, Pertsovskaya I, O’Driscoll M, Usmani OS. Peak inspiratory flow measured at different inhaler resistances in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:890–6.

Bloom CI, Douglas I, Olney J, D’Ancona G, Smeeth L, Quint JK. Cost saving of switching to equivalent inhalers and its effect on health outcomes. Thorax. 2019;74:1078–86.

Syk J, Vinge I, Sörberg M, Vahteristo M, Rytilä P. A multicenter, observational, prospective study of the effectiveness of switching from budesonide/formoterol Turbuhaler® to budesonide/formoterol Easyhaler®. Adv Ther. 2019;36:1756–69.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study. As it regards the publication of this article, Orion Pharma agreed to fund the Rapid Service Fee.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

We thank Piero Pollesello (Orion Pharma, Finland) for editorial coordination among co-authors, Shrestha Roy (Orion Pharma, India) for the graphic renditions, Hughes associates (Oxford, UK) for editorial assistance with the English language, and Alexander J.K. Wilkinson (Respiratory Department, East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust, Stevenage, UK) for useful discussion.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

FL, JC, GG, AP-S, ASP, PR, JS, MS, LT, AX, and TH contributed to the concept and design and drafting the manuscript.

Disclosures

As it regards relevant conflict of interest for this publication, FL, JC, GG, AP-S, ASP, JS, MS, LT, AX and TH report that, in the latest 5 years, they have received either research grants and/or speaker honoraria and/or support for conference attendance from Orion Pharma, where the Easyhaler was developed. PR is a full-time employee of Orion Pharma.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This review is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lavorini, F., Chudek, J., Gálffy, G. et al. Switching to the Dry-Powder Inhaler Easyhaler®: A Narrative Review of the Evidence. Pulm Ther 7, 409–427 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-021-00174-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-021-00174-5