Abstract

Nadofaragene firadenovec (Adstiladrin®) is an important bladder-sparing option in the treatment of patients with high-risk Bacillus Calmette Guérin (BCG)-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). Radical cystectomy is the recommended treatment in these patients; however, many are ineligible or refuse to undergo this major procedure and other options are limited. Intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec, a replication-deficient adenovirus-based gene therapy that causes localized expression of interferon (IFN) α2b in the bladder, is approved in the USA for the treatment of adults with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with carcinoma in situ (CIS) with or without papillary tumors. In a phase 3 clinical trial including patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS, nadofaragene firadenovec was efficacious in producing complete responses. Nadofaragene firadenovec had an acceptable safety profile and was generally well tolerated, with a small number of patients experiencing a grade 3 treatment-related adverse event and none experiencing a grade 4 or 5 drug-related adverse event. Cystectomy should be considered in patients who do not have a complete response to nadofaragene firadenovec or who have recurrence of CIS.

Plain Language Summary

Bacillus Calmette Guérin (BCG) is used in patients with high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) to reduce recurrence and prevent disease progression; however, a large proportion of patients develop BCG-unresponsive NMIBC. Radical cystectomy to remove the bladder is potentially curative in these patients, but many are unable or unwilling to undergo this major surgery. Nadofaragene firadenovec (Adstiladrin®) is a gene therapy administered into the bladder that causes localized expression of interferon (IFN) α2b, which promotes an anti-tumor immune response. It is approved in the USA for the treatment of adults with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with carcinoma in situ (CIS) with or without papillary tumors. In a pivotal clinical trial in patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS, nadofaragene firadenovec effectively produced complete responses (i.e. no detectable signs of bladder cancer). Nadofaragene firadenovec had an acceptable safety profile and was generally well tolerated, with most treatment-related adverse events being mild or moderate in severity. Thus, current evidence suggests that nadofaragene firadenovec is an important bladder-sparing treatment option in patients with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Digital Features for this Adis Drug Q&A can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24635778 |

Intravesical gene therapy that produces localized IFNα2b expression in the bladder |

Produces complete responses in patients with CIS with or without papillary tumors |

Has an acceptable safety profile and is generally well tolerated; most treatment-related adverse events are mild to moderate in severity |

What is the rationale for developing nadofaragene firadenovec in high-risk Bacillus Calmette Guérin (BCG)-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC)?

Bladder cancer is the sixth most common cancer in the USA, with a median age at diagnosis of 73 years [1]. The primary evaluation and initial treatment of bladder cancer involves transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) to completely remove all visible tumor, confirm the diagnosis and determine the stage and grade of the cancer [2]. Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) includes carcinoma in situ (CIS; flat, high-grade tumors), Ta papillary tumors (noninvasive) and T1 papillary tumors (invading the lamina propria) [2]. The management of NMIBC is stratified based on the risk of recurrence or disease progression, with CIS, high-grade T1 and certain Ta tumors considered to be at high risk [2, 3]. The rate of progression to muscle-invasive bladder cancer is 50% within 5 years in patients with untreated CIS and 30–40% within 10 years in patients with treated CIS [4].

After TURBT, intravesical (instilled into the bladder) Bacillus Calmette Guérin (BCG) therapy is used in the treatment of patients with high-risk NMIBC to reduce recurrence and prevent disease progression [2]. BCG (a live, attenuated form of the bacterium that causes bovine tuberculosis) stimulates an immune response against tumor cells [5]. Guidelines recommend an induction course of weekly BCG instillations for 6 weeks [2, 3]. A second BCG induction course can be effective in patients who have persistent or recurrent disease after a single induction course [3, 6]. In patients who have a complete response to BCG induction (one or two courses), maintenance therapy with BCG for 3 years is recommended [2, 3].

Although the majority of patients with high-risk NMIBC respond to BCG, up to ≈ 75% have disease recurrence within 5 years [7]. Patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC (including persistent or recurrent high-grade disease after adequate BCG treatment) are unlikely to benefit from further BCG therapy [8]. Radical cystectomy, to remove the bladder, is the recommended treatment in these patients [2, 3]. Radical cystectomy is potentially curative, with disease-specific survival rates of ≈ 80 to 90% [9, 10]. However, many patients are unfit or unwilling to undergo this procedure [11], which is associated with a 90-day major complication rate of 17% and a 90-mortality rate of 2–10% [6]. The limited number of treatment options for patients with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC who are ineligible for or refuse cystectomy thus represents a clinically important unmet need [6].

Recombinant human interferon (IFN) α has previously been investigated as a potential intravesical therapy for NMIBC, but with limited efficacy, likely due to the short exposure time to simple IFNα therapy [12]. To overcome this, nadofaragene firadenovec (nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg; Adstiladrin®), an adenoviral vector-based gene therapy, was developed to produce sustained IFNα expression in the bladder, thereby promoting an effective anti-tumor immune response [12]. Intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec is approved in the USA for the treatment of patients with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS with or without papillary tumors; the US prescribing information is summarized in Tables 1 and 2 [13].

How does nadofaragene firadenovec work?

Nadofaragene firadenovec is a replication-deficient and non-integrating adenoviral vector-based gene therapy consisting of a recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 vector with a transgene that encodes human IFNα2b [12, 13]. It also contains the excipient Syn3 [12], which enables viral transduction through the protective layer of the bladder to the underlying urothelium [14]. When instilled into the bladder, nadofaragene firadenovec delivers a copy of the transgene to the bladder urothelium, leading to transient local expression of IFNα2b [13]. A cytokine that elicits an anti-tumor immune response, IFNα has cytotoxic and anti-angiogenic effects in bladder cancer [15, 16].

The anti-tumor activity of nadofaragene firadenovec has been demonstrated in preclinical studies [17, 18]. Intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec led to tumor regression in an orthotopic human bladder cancer model in nude mice, which was associated with high urinary levels of IFN (indicative of effective gene transfer) [17, 18]. Furthermore, high levels of IFNα were observed in bladder tissue after treatment with nadofaragene firadenovec [17]. In a phase 1 dose-ranging trial in patients with recurrent NMIBC after BCG, intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec led to measurable concentrations of urinary IFNα in all patients, except at the lowest dose level (3 × 109 viral particles/mL in 75 mL); detectable levels of urinary IFNα were observed up to day 10 after instillation [19]. In a phase 2 clinical trial in patients with BCG-refractory or relapsed NMIBC, nadofaragene firadenovec treatment on day 1 led to detectable levels of IFNα in urine at day 2 up to day 12 [20].

The anti-adenovirus antibody response to nadofaragene firadenovec may be a potential predictor of the durability of treatment response [21]. In a phase 3 clinical trial in patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC, patients who were high-grade recurrence-free at 12 months after beginning nadofaragene firadenovec (responders) were significantly (p < 0.03) more likely to have serum anti-human adenovirus type-5 antibody titers > 800 at 3 months, peak titers > 800 and peak fold change from baseline > 8, than nonresponders [21].

What are the pharmacokinetic properties of nadofaragene firadenovec?

In the phase 1 and 2 clinical trials, only one patient receiving a second dose of nadofaragene firadenovec at the dose level of 3 × 1011 viral particles/mL (i.e. 2.25 × 1013 viral particles/instillation) in the phase 2 trial had measurable vector DNA in blood after intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec administration [13]. Measurable vector DNA was detected in urine from patients in both studies. At the same dose level, one of four patients in the phase 1 trial and 16 of 19 patients in the phase 2 trial had detectable levels of urinary vector DNA at day 14 and day 12 after administration, respectively [13].

Low, transient levels of the excipient Syn3 and IFNα were observed in serum after nadofaragene firadenovec administration in the phase 1 trial; peak concentrations occurred at 1–2 h and 24 h after administration for Syn3 and IFNα, respectively [19].

What is the efficacy of nadofaragene firadenovec in high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC?

Nadofaragene firadenovec is efficacious in patients with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC, as demonstrated in a pivotal, open-label, single-arm, multicenter, repeat-dose phase 3 trial [22]. This trial enrolled patients into two cohorts: those with CIS with or without high-grade Ta or T1 papillary tumors, and those with high-grade Ta or T1 papillary tumors without concomitant CIS [22]. This section, however, only focuses on the efficacy of nadofaragene firadenovec in the approved indication of high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS [13].

Screening assessments for the phase 3 trial, including urine cytology and biopsies, were performed up to 28 days before treatment initiation [22]. There was no central pathology review of cytology assessments. The trial enrolled patients aged ≥ 18 years with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC, including patients with persistent CIS or high-grade Ta or T1 disease within 12 months of initiating BCG, and patients who, after achieving a complete response to BCG, relapsed with high-grade Ta or T1 disease within 6 months or CIS within 12 months of their last exposure to BCG. Patients must have received adequate BCG therapy (≥ 5 of 6 induction doses and either ≥ 2 of 3 maintenance treatments or ≥ 2 of 6 doses of a second induction course), except those with high-grade T1 disease at the first evaluation after induction BCG (≥ 5 of 6 doses), who may also have been eligible in the absence of disease progression. Patients were required to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤ 2, a life expectancy of ≥ 2 years and to have completed an appropriate washout period if they had previously received immunosuppressive therapy, investigational drugs or intravesical therapy. Patients were also required to have all visible papillary tumors resected; those with T1 disease on TURBT underwent an additional TURBT 14–60 days before initiating study treatment. Obvious areas of CIS were also fulgurated before study treatment [22].

Exclusion criteria included upper urinary tract disease, urothelial carcinoma in the prostatic urethra, lymphovascular invasion, micropapillary bladder cancer, hydronephrosis due to tumor if the patient had T1 bladder cancer, current systemic therapy for bladder cancer and pelvic external beam radiotherapy within the previous 5 years [22].

All patients received nadofaragene firadenovec 75 mL (3 × 1011 viral particles/mL) instilled into the bladder via urinary catheter; no dose reduction was permitted [22]. Nadofaragene firadenovec was instilled for 1 h, during which the patients were asked to repeatedly reposition themselves to maximize exposure to the bladder surface. Patients received premedication with anticholinergics (unless contraindicated) prior to each instillation of nadofaragene firadenovec to reduce irritative voiding symptoms. Efficacy was assessed every 3 months to month 12 with urine cytology and cystoscopy (with biopsy if clinically indicated). Repeated doses of nadofaragene firadenovec were administered at months 3, 6 and 9 in the absence of high-grade disease recurrence. At month 12, patients underwent a mandatory biopsy of five bladder sites (dome, trigone, right and left lateral wall and posterior wall). Those who had had no evidence of high-grade recurrence were eligible to continue to receive nadofaragene firadenovec every 3 months [22]; the 5-year treatment and monitoring phase of the study is currently ongoing [23].

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients in the CIS cohort who had a complete response, defined as negative urine cytology and cystoscopy, as assessed by the treating physician, at any time within 12 months of treatment initiation with nadofaragene firadenovec [22]. If the patient had abnormal cells in their urine cytology but a normal cystoscopy and no biopsy, and subsequently had high-grade recurrence at a later date, the time of recurrence was backdated to the time of the abnormal urine cytology. The key secondary endpoint was the duration of complete response, defined as the time from first observed complete response to high-grade disease recurrence, disease progression or death in patients who achieved a complete response. Other secondary endpoints included duration of high-grade recurrence-free survival, radical cystectomy-free survival and overall survival. Efficacy analyses were done in the per protocol population and included only patients who met the protocol definition of BCG-unresponsive NMIBC [22].

At baseline, patients enrolled into the CIS cohort (n = 107) were mostly male (89%), white (93%), heavily pre-treated (57% had ≥ 3 previous courses of BCG) and had CIS only without papillary tumors (76%); the median age was 72 years and the median time from diagnosis was 20 months [22]. Four patients did not meet the definition of BCG-unresponsive NMIBC and were excluded from the efficacy analysis [22].

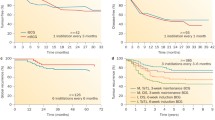

Over half of the 103 evaluable patients with CIS who received nadofaragene firadenovec in the trial had a complete response within 12 months (primary endpoint) (Table 3) [22]. Of these patients, all had achieved a complete response at month 3 and the median duration of response was 9.7 months (Table 3). The proportion of patients with high-grade recurrence-free survival through to 12 months is also presented in Table 3. At month 12, 24% of all evaluable patients (i.e. 46% of patients who had a complete response) were high-grade recurrence-free [22].

In evaluable patients with CIS, 73 (71%) patients had developed recurrent high-grade NMIBC and five (5%) had progressed to muscle-invasive bladder cancer at month 12 [22]. Three patients who progressed to muscle-invasive disease had a history of T1 tumors and two patients had recurrence with CIS (one at month 3 and one at month 9). In total, 29% of patients underwent cystectomy; the median time to cystectomy was 8.9 months. In a post-hoc exploratory analysis, patients who had achieved a complete response had a longer time to cystectomy than patients who did not (median 11.4 months vs 6.4 months; p = 0.043) [22]. Of 30 patients who underwent cystectomy and for whom pathological data were available, three were upstaged to muscle-invasive disease at cystectomy; one of these patients had recurrence with CIS after nadofaragene firadenovec and subsequently progressed after pembrolizumab treatment [22]. The US prescribing information for nadofaragene firadenovec includes a regulatory warning on the risk of disease progression to muscle-invasive or metastatic bladder cancer when cystectomy is delayed in patients with BCG-unresponsive CIS (Table 2) [13]. Cystectomy should be considered in patients who do not have a complete response 3 months after initiating nadofaragene firadenovec or if CIS recurs (Table 2) [13].

In subgroup analyses conducted at month 3 and month 15 of treatment, nadofaragene firadenovec showed similar complete response rates at both timepoints irrespective of sex (male or female), age (< 70 or ≥ 70 years), baseline disease status (BCG-refractory or BCG-relapsed) and number of prior lines of therapy (≤ 3 or > 3), BCG courses (≤ 3 or > 3) or non-BCG regimens (0 or ≥ 1) [24]. The median duration of response was also similar across the subgroups, except patients who had ≤ 3 prior courses of BCG had a significantly longer median duration of response than those who had > 3 BCG courses (12.7 months vs 5.0 months; p = 0.0172) at 15 months [24].

The response to nadofaragene firadenovec was durable at month 24 (restricted-mean follow up of 23.5 months; 18% of patients treated for 24 months; in all 103 evaluable patients with CIS) [25] and month 36 (mean follow up of 42.1 months; 12% of patients treated for 36 months; in all 107 patients with CIS) [23]. Of the 103 evaluable patients, 19% and 14% (i.e. 36% and 26% of those who had a complete response) remained high-grade recurrence-free at month 24 [25] and month 36 [23], respectively. In patients who had achieved a complete response, the Kaplan-Meir estimated median duration of complete response was 9.7 (95% CI 9.2–24.0) months at month 36; the probability of a response duration of ≥ 36 months was 34% (95% CI 22–47) [23]. In all evaluable patients, the Kaplan-Meir estimated cystectomy-free survival was 65% (95% CI 54–73) at month 24 [25] and 54% (95% CI 43–63) at month 36 [23]. The Kaplan-Meir estimated overall survival was 94% (95% CI 87–98) at month 24 [25] and 90% (95% CI 82–95) at month 36 [23].

What is the safety and tolerability profile of nadofaragene firadenovec?

Nadofaragene firadenovec has an acceptable safety profile and is generally well tolerated in patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC [22]. The safety and tolerability of nadofaragene firadenovec were assessed in 157 patients who received ≥ 1 dose of the drug in the phase 3 clinical trial, including 107 patients who had CIS with or without papillary tumors and 50 patients who had high-grade Ta or T1 papillary tumors only. Overall, 70% of patients had a treatment-related adverse event (TRAE) with nadofaragene firadenovec. Most TRAEs were grade 1–2 in severity. The most common (occurring in ≥ 10% of patients) grade 1–2 TRAEs were discharge around the catheter during instillation (25%), fatigue (20%), bladder spasms (15%), micturition urgency (strong need to urinate; 14%), chills (12%), dysuria (painful urination; 11%) and pyrexia (10%) [22].

Grade 3 TRAEs occurred in six (4%) patients, including two cases of micturition urgency and one case each of bladder spasms, hypertension, syncope (fainting) and urinary incontinence [22]. There were no grade 4–5 drug-related adverse events (AEs); however, a grade 4 AE of sepsis was considered to be procedure related. Serious AEs that were considered drug or procedure related occurred in 2% of patients; these were the cases of syncope and sepsis previously mentioned, and one case of hematuria (blood in urine; considered procedure related) [22].

Three (2%) patients discontinued nadofaragene firadenovec treatment due to AEs, including one patient due to discharge around the catheter during instillation, one due to bladder spasms, and one due to benign neoplasm of the bladder (urothelial hyperplasia; considered drug related) [22]. Dosage interruption due to an adverse reaction occurred in 34% of patients, including due to instillation site discharge, bladder spasms and micturition urgency (each occurring in > 10% of patients) [13].

Longer-term data indicated that nadofaragene firadenovec continued to be generally well tolerated in patients with CIS at month 24 [25] and month 36 [23], with no new grade 4–5 TRAEs reported [25].

What is the current clinical role of nadofaragene firadenovec in high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC?

Nadofaragene firadenovec is an important bladder-sparing option in patients with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS with or without papillary tumors. It has the potential benefit of intravesical administration [13], which can maximize the exposure of tumors to the drug, while limiting systemic exposure and potential AEs [26].

Nadofaragene firadenovec produced complete responses in over half of patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS in a pivotal phase 3 trial [22]. All complete responses were achieved early (by month 3) [22] and high-grade recurrence-free survival was durable at month 36 [23]. Limitations of this trial include the absence of central pathology review and non-standardized methodology for TURBT, screening and efficacy assessments; however, high-grade recurrences were backdated to first abnormal cytology (if applicable) and bladder biopsy was mandated at month 12 to confirm the presence or absence of high-grade disease recurrence [22]. Longer-term evaluation of the efficacy of nadofaragene firadenovec, including in terms of progression-free and overall survival, will be valuable [11].

Progression to muscle-invasive or metastatic bladder cancer, which can be lethal, is a risk associated with delaying cystectomy in patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS (Table 2) [13]. In the pivotal phase 3 trial in patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC, five patients with CIS had progressed to muscle-invasive disease at month 12, including three patients who were upstaged at cystectomy [22]. Longer-term data is required to determine whether delaying cystectomy in patients treated with nadofaragene firadenovec is associated with greater disease-related mortality [27]. The US prescribing information for nadofaragene firadenovec recommends considering cystectomy for patients who do not have a complete response to treatment at 3 months or in whom CIS recurs (Table 2) [13].

Nadofaragene firadenovec has an acceptable safety profile and is generally well tolerated in patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC [22]. Among patients with CIS or high-grade Ta or T1 papillary tumors alone, the most common TRAEs were discharge around the catheter during instillation, fatigue and bladder spasms. Most TRAEs were grade 1–2 in severity and few patients discontinued nadofaragene firadenovec due to AEs [22]. However, immunosuppressed or immune-deficient individuals should not come into contact with nadofaragene firadenovec due to the possible risk of disseminated adenovirus infection (Table 2) [13].

In patients with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC, radical cystectomy is recommended [2, 3, 6]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that if the patient is ineligible or refuses cystectomy, other options include nadofaragene firadenovec, intravesical chemotherapy and parenteral pembrolizumab (in select patients) [2]. Intravesical valrubicin, approved for BCG-refractory CIS only [28], is associated with a complete response rate of 18% at 6 months [29] and is not frequently used in clinical practice due to its modest efficacy [30]. Pembrolizumab is associated with a complete response rate of 41% at 3 months and a median duration of response of 16.2 months [31]. Cross-study comparison of the relative efficacy of nadofaragene firadenovec and pembrolizumab is highly uncertain due to differences in the evaluation of outcomes and the lack of comparators in the pivotal trials for these drugs [27]. However, nadofaragene firadenovec appears to have an improved tolerability profile compared with pembrolizumab, with 4% of patients experiencing a grade 3 TRAE and none experiencing grade 4 or 5 drug-related AEs [22]. By contrast, pembrolizumab was associated with grade 3–4 TRAEs in 13% of patients [31]. Regulatory warnings for pembrolizumab include those on immune-mediated AEs and infusion-related reactions that may be severe or fatal/life threatening [32]. Moreover, nadofaragene firadenovec has the potential benefit of an infrequent dosage schedule (every 3 months intravesically) [13] compared with pembrolizumab (every 3 or 6 weeks intravenously) [32]. Comparative studies would be valuable to determine the relative efficacy and tolerability of nadofaragene firadenovec and other treatments in high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC.

As new therapies for BCG-unresponsive NMIBC emerge, the cost-effectiveness of each treatment needs to be considered to determine the optimal therapeutic approach [30]. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review assessed the cost effectiveness of nadofaragene firadenovec in patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS using a semi-Markov model with a 3-month cycle, lifetime horizon and 3% discount rate from a US healthcare sector perspective [27]. At a placeholder annual price of $164,337, nadofaragene firadenovec was predicted to cost $151,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained versus a hypothetical comparator with no efficacy [27]. In a similar model with a placeholder price of $191,000, nadofaragene firadenovec was associated with a cost of $263,000 per QALY gained versus a comparator with efficacy based on valrubicin; nadofaragene firadenovec was not cost effective at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $150,000 per QALY gained [33]. The limitations of these cost-effectiveness models include uncertainty around the long-term efficacy of nadofaragene firadenovec and the use of placeholder prices and hypothetical comparators; therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution [27]. Comparative studies of nadofaragene firadenovec and other treatments for BCG-unresponsive NMIBC would be useful to obtain improved cost-effectiveness estimates [33].

As many patients do not have a complete response to nadofaragene firadenovec or will later experience disease recurrence [22], there is a need to predict which patients will receive the most clinical benefit from treatment [34]. Anti-human adenovirus type 5 antibody titers are a potential biomarker to predict the durability of response to nadofaragene firadenovec [21]. Further research on identifying and validating biomarkers of treatment response to nadofaragene firadenovec is needed.

Change history

21 March 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-024-01061-0

References

National Cancer Institute. SEER cancer stat facts: bladder cancer. 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer, version 3.2023. 2023. https://www.nccn.org/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Chang SS, Boorjian SA, Chou R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO guideline. J Urol. 2016;196(4):1021–9.

Mirabal JR, Taylor JA, Lerner SP. CIS of the bladder: significance and implications for therapy. Bladder Cancer. 2019;5(3):193–204.

Goldberg IP, Lichtbroun B, Singer EA, et al. Pharmacologic therapies for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: current and future treatments. Arch Pharmacol Ther. 2022;4(1):13–22.

Kamat A, Colombel M, Sundi D, et al. BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: recommendations from the IBCG. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14(4):244–55.

Sfakianos JP, Kim PH, Hakimi AA, et al. The effect of restaging transurethral resection on recurrence and progression rates in patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer treated with intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Urol. 2014;191(2):341–5.

US Food & Drug Administration. BCG-unresponsive nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: developing drugs and biologics for treatment guidance for industry. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Herr HW, Sogani PC. Does early cystectomy improve the survival of patients with high risk superficial bladder tumors? J Urol. 2001;166(4):1296–9.

Nieder AM, Simon MA, Kim SS, et al. Radical cystectomy after bacillus Calmette-Guerin for high-risk Ta, T1, and carcinoma in situ: defining the risk of initial bladder preservation. Urology. 2006;67(4):737–41.

Bree KK, Brooks NA, Kamat AM. Current therapy and emerging intravesical agents to treat non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2021;35(3):513–29.

Duplisea JJ, Mokkapati S, Plote D, et al. The development of interferon-based gene therapy for BCG unresponsive bladder cancer: from bench to bedside. World J Urol. 2019;37(10):2041–9.

Ferring Pharmaceuticals. ADSTILADRIN® (nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg) suspension, for intravesical use: US prescribing information. 2023. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Yamashita M, Rosser CJ, Zhou JH, et al. Syn3 provides high levels of intravesical adenoviral-mediated gene transfer for gene therapy of genetically altered urothelium and superficial bladder cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9(8):687–91.

Papageorgiou A, Dinney CP, McConkey DJ. Interferon-alpha induces TRAIL expression and cell death via an IRF-1-dependent mechanism in human bladder cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6(6):872–9.

Dinney CP, Bielenberg DR, Perrotte P, et al. Inhibition of basic fibroblast growth factor expression, angiogenesis, and growth of human bladder carcinoma in mice by systemic interferon-alpha administration. Cancer Res. 1998;58(4):808–14.

Benedict WF, Tao Z, Kim CS, et al. Intravesical Ad-IFNalpha causes marked regression of human bladder cancer growing orthotopically in nude mice and overcomes resistance to IFN-alpha protein. Mol Ther. 2004;10(3):525–32.

Tao Z, Connor RJ, Ashoori F, et al. Efficacy of a single intravesical treatment with Ad-IFN/Syn 3 is dependent on dose and urine IFN concentration obtained: implications for clinical investigation. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13(2):125–30.

Dinney CP, Fisher MB, Navai N, et al. Phase I trial of intravesical recombinant adenovirus mediated interferon-α2b formulated in Syn3 for Bacillus Calmette-Guérin failures in nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol. 2013;190(3):850–6.

Shore ND, Boorjian SA, Canter DJ, et al. Intravesical rAd-IFNα/Syn3 for patients with high-grade, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin-refractory or relapsed non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a phase II randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3410–6.

Mitra AP, Narayan VM, Mokkapati S, et al. Antiadenovirus antibodies predict response durability to nadofaragene firadenovec therapy in BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: secondary analysis of a phase 3 clinical trial. Eur Urol. 2022;81(3):223–8.

Boorjian SA, Alemozaffar M, Konety BR, et al. Intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec gene therapy for BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a single-arm, open-label, repeat-dose clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(1):107–17.

Boorjian SA, Narayan VM, Konety BR, et al. Efficacy of intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec for patients with BCG-unresponsive carcinoma in situ of the bladder: 36-month follow-up from a phase 3 trial [abstract plus poster 164]. In: Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Annual Meeting. 2023.

Narayan V, Boorjian S, Alemozaffer M, et al. Subgroup analyses of the phase 3 study of intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec in patients with high-grade, BCG-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) [abstract no. P0745 plus poster]. In: Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Annual Meeting. 2020.

Schuckman A, Lotan Y, Boorjian S, et al. Efficacy of intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec for patients with carcinoma in situ (CIS), BCG-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC): longer-term follow-up from the phase III trial [abstract no. MP16-01 plus poster]. In: American Urological Association (AUA) Annual Meeting. 2021.

Shen Z, Shen T, Wientjes MG, et al. Intravesical treatments of bladder cancer: review. Pharm Res. 2008;25(7):1500–10.

Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Nadofaragene firadenovec and oportuzumab monatox for BCG-unresponsive, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: effectiveness and value (final report). 2021. https://icer.org/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Endo Pharmaceuticals Solutions Inc. VALSTAR® (valrubicin) solution, for intravesical use: US prescribing information. 2019. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Dinney CP, Greenberg RE, Steinberg GD. Intravesical valrubicin in patients with bladder carcinoma in situ and contraindication to or failure after bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(8):1635–42.

Packiam VT, Richards J, Schmautz M, et al. The current landscape of salvage therapies for patients with bacillus Calmette-Guérin unresponsive nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2021;31(3):178–87.

Balar AV, Kamat AM, Kulkarni GS, et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for the treatment of high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer unresponsive to BCG (KEYNOTE-057): an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):919–30.

Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC. KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) injection, for intravenous use: US prescribing information. 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Joshi M, Atlas SJ, Beinfeld M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of nadofaragene firadenovec and pembrolizumab in Bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Value Health. 2022;26(6):823–32.

Valenza C, Antonarelli G, Giugliano F, et al. Emerging treatment landscape of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022;22(6):717–34.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript was reviewed by: S. Mokkapati, Department of Urology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA; K. A. Richards, Department of Urology, The University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA. During the peer review process, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, the marketing authorization holder of nadofaragene firadenovec, was also offered an opportunity to provide a scientific accuracy review of their data. Changes resulting from comments received were made on the basis of scientific and editorial merit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The preparation of this review was not supported by any external funding.

Authorship and conflict of interest

T. Nie is a salaried employee of Adis International Ltd/Springer Nature and declares no relevant conflicts of interest. All authors contributed to this article and are responsible for its content.

Ethics approval, Consent to participate, Consent for publication, Availability of data and material, Code availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised: The original article has been revised due to retrospective open choice order.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nie, T. Nadofaragene firadenovec in high-risk Bacillus Calmette Guérin unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a profile of its use. Drugs Ther Perspect 40, 1–8 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-024-01045-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-024-01045-0