Abstract

Oritavancin, a long-acting lipoglycopeptide, is the first single-dose intravenous (IV) antibacterial therapy approved in the USA for the treatment of adult patients with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSIs) caused or suspected to be caused by susceptible isolates of designated gram-positive microorganisms. With its well-established antibacterial activity, efficacy and safety profiles, a new IV formulation of oritavancin (KIMYRSA™) has been developed to offer a more convenient treatment option for patients with ABSSSIs. Relative to the originally approved IV formulation of oritavancin (ORBACTIV®), the new IV formulation has better diluent compatibility, simpler preparation steps, a shorter infusion time of 1 h in a lower infusion volume of 250 mL. Approval was based on results of a phase 1 study in which pharmacokinetic similarity between the two IV formulations of oritavancin was demonstrated in patients with ABSSSIs. The tolerability profile of the new IV formulation of oritavancin revealed no new safety signals.

Plain Language Summary

Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSIs) are heterogeneous bacterial infections that can pose a significant burden on healthcare systems. In an attempt to optimize patient outcomes and healthcare utilizations, single-dose regimens have been developed as an alternative to multi-dose and multi-day regimens for ABSSSIs. Oritavancin is the first single-dose intravenous (IV) antibacterial therapy approved in the USA for the treatment of adult patients with ABSSSIs. With its well-established efficacy and safety profiles, a new IV formulation of oritavancin (KIMYRSA™) has been developed, which has a shorter infusion time and a smaller infusion volume than the originally approved IV formulation (ORBACTIV®). The pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of oritavancin were similar between the two IV formulations. The new IV formulation of oritavancin is a convenient, effective treatment option for patients with ABSSSIs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Digital Features for this Adis Drug Q&A can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17118950. |

Has better diluent compatibility, full dose in a single vial, a shorter infusion time and a lower infusion volume than the original IV formulation. |

Similar pharmacokinetic profile to that of the original IV formulation. |

Generally well tolerated with no new safety signals. |

What is the rationale for developing a new intravenous (IV) formulation of oritavancin?

Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSIs) are heterogeneous bacterial infections that can range from mild local infections to life-threatening systemic infections, and include wound infection, cellulitis/erysipelas and major cutaneous abscesses [1, 2]. The most common causative pathogens for ABSSSIs are gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus [including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA)] and Streptococcus pyogenes [1, 2].

With many antibacterial agents being available for the treatment of ABSSSIs, the choice of appropriate antibacterial therapy is based on several factors, including site of infection, causative pathogen, local antibacterial resistance patterns, drug characteristics (e.g. potential drug-drug interactions, efficacy and safety profiles, cost and ability for easy transition at discharge) and patient characteristics (e.g. presence of comorbidities) [1,2,3,4]. Vancomycin, linezolid, ceftaroline, daptomycin and clindamycin are among the recommended first-line parenteral antibacterial therapy in the 2014 Infectious Diseases Society of America practice guidelines for skin and soft tissue infections [4].

Many patients with ABSSSIs, including those with minimal comorbidity and mild or no systemic signs of infection, are hospitalized for several days solely to receive multi-dose and multi-day parenteral antibacterial therapy, which poses a significant financial burden on healthcare systems [5,6,7]. Based on any comorbidities and infection severity, hospitalized patients receiving multi-dose and multi-day parenteral antibacterial therapy may transition to outpatient parenteral or oral antibacterial therapy (OPAT) [7, 8]. However, transitioning patients to OPAT may not overcome the limitations of multiple drug administrations, dosage adjustment, therapeutic drug monitoring and treatment non-adherence, which can lead to poor clinical outcomes [8].

In an attempt to decrease healthcare costs and improve clinical outcomes, single-dose antibacterial treatments, such as oritavancin and dalbavancin, have been developed as an alternative to multi-dose and multi-day antibacterial treatment for ABSSSIs [3, 9]. Oritavancin, a long-acting lipoglycopeptide, is the first single-dose intravenous (IV) antibacterial therapy approved in the USA for the treatment of adult patients with ABSSSI caused by, or suspected to be caused by, susceptible gram-positive microorganisms [10, 11]. The originally approved IV formulation of oritavancin (ORBACTIV®) is prepared from three separate vials using dextrose 5% in sterile water for dilution, and infused over 3 h with an infusion volume of 1 L [11]. A newly developed IV formulation of oritavancin (KIMYRSA™) includes the solubilizer hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD); it can be prepared from a single vial, and has a better diluent compatibility, a shorter infusion time of 1 h and a smaller infusion volume of 250 mL than the originally approved IV formulation [10, 12]. Table 1 provides a summary of the prescribing information of the new IV formulation of oritavancin in the USA [10]. Consult local prescribing information for further details.

What are the antibacterial effects of oritavancin?

Oritavancin, a semi-synthetic lipoglycopeptide analogue of vancomycin, has multiple mechanisms of action where it inhibits the transglycosylation (polymerization) and transpeptidation (crosslinking) steps of bacterial cell wall biosynthesis by binding to the step peptide of peptidoglycan precursors and peptide bridging segments of the cell wall, respectively [13]. Additionally, oritavancin disrupts bacterial membrane integrity, leading to the depolarization and increased permeability, and cell death [13, 14].

Oritavancin has demonstrated antibacterial activity, both in vitro and in clinical infections, against clinically relevant isolates of gram-positive bacteria associated with ABSSSIs [10]. In the US prescribing information, specified pathogens are Staphylococcus aureus [including methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and MRSA isolates], Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus anginosus group (including S. anginosus, S. intermedius and S. constellatus) and Enterococcus faecalis (vancomycin-susceptible isolates only) [10]. CLSI identified minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) breakpoints for susceptibility of oritavancin against specified microorganisms are: S. aureus including MRSA (≤ 0.12 μg/mL); Streptococcus species (≤ 0.25 μg/mL); vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis (≤ 0.12 μg/mL) [15].

Oritavancin was tested against gram-positive clinical isolates collected worldwide, or in the USA and/or Europe as part of the 1997–2016 SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program [16,17,18,19,20]. Oritavancin exhibited potent in vitro activity against S. aureus including MSSA (n = 79,287; 99.7–99.9% susceptible) [17,18,19,20]; viridans group streptococci (VGS) including the S. anginosus group (n = 2293; 100%) [19, 20]; β-haemolytic streptococci (BHS) including S. agalactiae, S. dysgalactiae and S. pyogenes (n = 5212; 99.4–99.7%) [19, 20]; and E. faecalis (n = 5714; 99.5–99.9%) [19, 20], with oritavancin MIC values required to inhibit 90% of isolates (MIC90) being 0.03–0.06 μg/mL against S. aureus, 0.06 μg/mL against VGS and E. faecalis, and 0.12–0.25 μg/mL against BHS [17,18,19,20]. Oritavancin also exhibited potent in vitro activity against gram-positive pathogens exhibiting resistance to ≥ 1 clinically relevant antibacterial drugs, including MRSA (n = 46,373; 99.6–99.9%) [17, 20] and vancomycin-resistant enterococci isolates (n = 7615; 92.2–98.3%) when using the breakpoint for vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis [16]; MIC90 values against respective isolates were 0.06 μg/mL and 0.06–0.12 μg/mL. Overall, in vitro activity of oritavancin was consistent over time and comparable between the isolates collected in the USA and Europe [16,17,18,19,20].

In vitro, oritavancin exhibits synergistic bactericidal activity when used in combination with gentamicin, moxifloxacin or rifampicin against isolates of MSSA, with gentamicin or linezolid against isolates of vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA), heterogeneous VISA and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA), and with rifampin against isolates of VRSA [10]. No in vitro antagonism has been demonstrated between oritavancin and gentamicin, moxifloxacin, linezolid or rifampin [10].

In vitro, oritavancin demonstrated a concentration-dependent bactericidal activity against S. aureus, S. pyogenes and E. faecalis [10]. Moreover, in in vitro time-kill kinetics studies, oritavancin exerted sustained bactericidal activity (≥ 3-log kill relative to starting inoculum) against isolates of MSSA, MRSA, and vancomycin-susceptible and vancomycin-resistant enterococci in a concentration-dependent manner [21, 22]. Relative to other evaluated antibacterial agents (i.e. ceftaroline, daptomycin, dalbavancin, linezolid, tedizolid, telavancin and vancomycin), oritavancin exhibited the most rapid bactericidal activity against MSSA and MRSA isolates [22]. Oritavancin also exhibited potent in vitro activity against biofilms of MSSA, MRSA and VRSA, and increased the permeability of stationary phase cells in a concentration-dependent manner [12]. The antibacterial efficacy of oritavancin appeared to correlate with the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC)/MIC ratio [10].

There was no evidence of resistance to oritavancin in clinical studies but in vitro, the emergence of S. aureus and E. faecalis strains resistant to oritavancin has been observed in serial passage studies [10].

What is the pharmacokinetic profile of oritavancin?

Oritavancin exhibits linear pharmacokinetics at a dose up to 1200 mg, with the mean population-predicted concentration time profile displaying a multi-exponential decline with a long terminal half-life [10, 11]. It is extensively distributed into tissues and is ≈ 85% bound to human plasma proteins. Following a single dose of oritavancin 800 mg in healthy individuals, oritavancin exposure in skin blister fluid is ≈ 20%. Oritavancin is slowly excreted unchanged, with less than 1% and 5% of the dose recovered in faeces and urine, respectively. In a population pharmacokinetic analysis, oritavancin has a total volume of distribution of ≈ 87.6 L and clearance of 0.445 L/h; the terminal half-life is ≈ 245 h. The pharmacokinetics of oritavancin are not affected to any clinically relevant extent by age, weight, gender, race or mild to moderate renal or hepatic impairment [10, 11].

The pharmacokinetic similarity between the new and original IV formulations of oritavancin was demonstrated in a randomized, open-label, phase 1 pharmacokinetic study where eligible patients with ABSSSIs were randomized to receive a single-dose of IV oritavancin 1200 mg in 250 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride over a 1 h infusion (i.e. new IV formulation), or in 1000 mL of dextrose 5% in sterile water over a 3 h infusion (i.e. original IV formulation) [12, 23]. Following administration of a single-dose IV oritavancin 1200 mg, the mean AUC from time zero to 72 h and 168 h was similar between the two IV formulations, with the mean peak concentration and time to reach maximum concentration being higher and faster with the new 1 h infused IV formulation due to the shorter infusion time (Table 2) [12].

What is the overall clinical profile of oritavancin?

The efficacy and safety of oritavancin for the treatment of ABSSSIs are well established with the original 3 h infused IV formulation [24,25,26,27,28,29] and has been extensively reviewed previously [30,31,32]. There are no specific clinical studies designed to assess the efficacy of the new IV formulation of oritavancin for the treatment of ABSSSIs.

In two identically designed, randomized, double-blind, noninferiority phase 3 SOLO I and SOLO II trials (n = 1987), the efficacy of a single-dose regimen of IV oritavancin 1200 mg infused over 3 h was compared to a 7–10 days regimen of IV vancomycin 1 g or 15 mg/kg twice daily in patients with ABSSSIs [25, 26]. In each trial, oritavancin was noninferior to vancomycin in terms of the clinical response rate (SOLO I 82.3% vs 78.9%; SOLO II 80.1% vs 82.9%, primary endpoint in both trials), the investigator-assessed clinical cure rate (79.6% vs 80.0%; 82.7% vs 80.5%) and the proportion of patients achieving a ≥ 20% reduction in lesion size (86.9% vs 82.9%; 85.9% vs 85.3%) [25, 26]. In subgroup analyses, some of which were post-hoc, the primary and secondary efficacy endpoints were generally similar between the treatment groups regardless of treatment setting (inpatient or outpatient), disease severity, infection type, lesion type, baseline pathogen, geographic region, age, sex, race, weight or baseline kidney or liver function [24,25,26,27, 29].

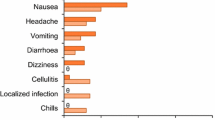

In the SOLO I and II trials, oritavancin was generally well tolerated and exhibited a safety profile similar to that of vancomycin [28]. In patients treated with oritavancin or vancomycin, the incidence of any-grade adverse events (AEs), serious AEs and treatment discontinuation due to AEs was similar between the treatment groups (55.3%, 5.8% and 3.7% vs 56.9%, 5.9% and 4.2%). Most AEs were of mild to moderate severity and the most common AEs (≥ 3% incidence) with oritavancin included nausea (9.9% vs 10.5% with vancomycin), headache (7.1% vs 6.7%), vomiting (4.6% vs 4.7%), cellulitis (3.8% vs 3.3%), diarrhoea (3.7% vs 3.3%), constipation (3.4% vs 3.9%), infusion site extravasation (3.4% vs 3.4%), pyrexia (3.1% vs 3.2%) and pruritus (3.0% vs 7.4%). The most commonly reported serious AEs with oritavancin were cellulitis (1.1%) and osteomyelitis (0.4%), which were also the most common AEs leading to discontinuation of oritavancin (0.4% and 0.3%, respectively). The incidences of infections and infestations, abscesses or cellulitis, and hepatic and cardiac AEs were slightly higher with oritavancin than with vancomycin; however, more than 80% of these AEs were of mild to moderate severity [28].

Real-world experience in 112 patients with a confirmed or suspected gram-positive infection further supported the clinical benefits of oritavancin demonstrated in the SOLO I and II trials [33]. Oritavancin was associated with high positive clinical response (92.8%) and microbial eradication rate (90.0%), with < 5% of patients hospitalized for worsening or recurrence of the index infection within 28 days of oritavancin treatment. The tolerability profile of oritavancin was consistent to that observed in the SOLO I and II trials [33].

The tolerability profile of the new IV formulation of oritavancin was similar to that of the original IV formulation and revealed no new safety signals in the phase 1 pharmacokinetic study [12]. In this study, diarrhoea, chills, pyrexia, pruritus, infection and headache occurred in ≥ 2 patients (at least 4% of patients) receiving the new IV formulation of oritavancin. No kidney-related AEs were reported for any of the patients treated with the new formulation of oritavancin and there was no evidence that oritavancin with HPβCD was associated with increased renal toxicity [12]. Positive antiglobulin tests were reported in 2% (1/50) and 9.6% (5/52) of patients receiving the new and original IV formulations of oritavancin, respectively; positive indirect antiglobulin tests have the potential to interfere with cross-matching before blood transfusion [10, 12]. There were no reports of haemolysis in patients who had positive indirect or direct antiglobulin tests [10, 12].

What is the current clinical position of the new IV formulation of oritavancin?

With the majority of standard-of-care IV antibacterial treatment regimens for ABSSSIs requiring multi-dose and multi-day administration, IV oritavancin provides an effective single-dose regimen for ABSSSIs that can facilitate outpatient treatment and eliminate the need for unnecessary hospitalization, especially for patients with mild to moderate disease severity and minimal comorbidity [12]. The new IV formulation of oritavancin, which has a similar pharmacokinetic profile to that of the original IV formulation, is a convenient, effective treatment option for patients with ABSSSIs. Relative to the original IV formulation, the new IV formulation of oritavancin requires only a single vial during preparation, and has better diluent compatibility, a lower infusion volume and a shorter infusion time, thereby potentially improving patient convenience and optimizing the use of clinical resources.

The antibacterial activity, as well as efficacy and safety profiles of oritavancin for the treatment of ABSSSIs are well established with the original IV formulation. Oritavancin exhibits potent in vitro antibacterial activity against gram-positive bacteria associated with ABSSSI, including MRSA, and has noninferior efficacy and a similar tolerability profile to that of vancomycin. In addition, the new IV formulation of oritavancin revealed no new safety signals in the phase 1 pharmacokinetic study in patients with ABSSSIs.

Results of systematic reviews and meta-analyses comparing the efficacy of newer glycopeptides to standard care for ABSSSIs have indicated that a single-dose 3-h infusion oritavancin is less costly and has comparable efficacy and safety [34]. To improve patient clinical outcomes and resource utilization, several centres in the USA have implemented oritavancin as part of a multidisciplinary treatment program for ABSSSIs [12]. Indeed, real-world studies have suggested potential clinical and economic benefits associated with the single-dose IV oritavancin regimen in patients with ABSSSIs where the treatment reduced disease progression rates [6], infection sequelae from ABSSSI treatment failures [35], 30-day hospital readmission rates [6, 35, 36] and/or length of hospital stays without affecting readmission rates [5, 6]. Furthermore, pharmacoeconomic analyses (from the hospital perspective) of oritavancin versus vancomycin in patients with confirmed or suspected gram-positive ABSSSIs and risk of MRSA in the USA indicate that oritavancin is associated with substantial healthcare cost savings by lowering drug administration burden and reducing hospital admissions [37, 38]. Although these studies have been conducted with the original 3 h infused IV formulation of oritavancin, similar clinical and economic benefits are expected with the new 1 h infused IV formulation of oritavancin [12].

Additional studies in real-world settings assessing the economic benefits between single-dose 1-h infusion oritavancin and daily injections or oral antibiotic therapies in ABSSSIs would be of interest.

Change history

17 February 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-022-00901-1

References

Golan Y. Current treatment options for acute skin and skin-structure infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(Suppl 3):S206–12.

Bassetti M, Magnasco L, Del Puente F, et al. Role of new antibiotics in the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2020;33(2):110–20.

Jaffa RK, Pillinger KE, Roshdy D, et al. Novel developments in the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20(12):1493–502.

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):147–59.

Helton B, MacWhinnie A, Minor SB, et al. Early directed oritavancin therapy in the emergency department may lead to hospital avoidance compared to standard treatment for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: a real-world retrospective analysis. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2020;7(Suppl 1):20–9.

Whittaker C, Lodise TP, Nhan E, et al. Expediting discharge in hospitalized, adult patients with skin and soft tissue infections who received empiric vancomycin therapy with oritavancin: description of findings from an institutional pathway. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2020;7(Suppl 1):30–5.

Saddler K, Zhang J, Sul J, et al. Improved economic and clinical outcomes with oritavancin versus a comparator group for treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections in a community hospital. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0248129.

Williams B, Muklewicz J, Steuber TD, et al. Comparison of inpatient standard-of-care to outpatient oritavancin therapy for patients with acute uncomplicated cellulitis. J Pharm Pract. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/08971900211021258.

Co D, Roebuck L, VanLandingham J. Evaluation of oritavancin use at a community hospital. Hosp Pharm. 2018;53(4):272–6.

Melinta Therapeutics. KIMYRSA™ (oritavancin) for injection, for intravenous use [US prescribing information]. 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/214155s001lbl.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec 2021.

Melinta Therapeutics. ORBACTIV® (oritavancin) for injection, for intravenous use [US prescribing information]. 2021. http://www.orbactiv.com/. Accessed 8 Dec 2021.

Melinta Therapeutics. Clinical and economic considerations for KIMYRSATM (oritavancin) for injection in support of formulary adoption. Illinois: Melinta Therapeutics; 2021.

Zhanel GG, Schweizer F, Karlowsky JA. Oritavancin: mechanism of action. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(Suppl 3):S214–9.

Belley A, McKay GA, Arhin FF, et al. Oritavancin disrupts membrane integrity of Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci to effect rapid bacterial killing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(12):5369–71.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing 2020. https://www.nih.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/CLSI-2020.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec 2021.

Pfaller MA, Cormican M, Flamm RK, et al. Temporal and geographic variation in antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance patterns of enterococci: results from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program, 1997–2016. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(Suppl 1):S54-s62.

Diekema DJ, Pfaller MA, Shortridge D, et al. Twenty-year trends in antimicrobial susceptibilities among Staphylococcus aureus from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(Suppl 1):S47–53.

Sader HS, Castanheira M, Arends SJR, et al. Geographical and temporal variation in the frequency and antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria isolated from patients hospitalized with bacterial pneumonia: results from 20 years of the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (1997–2016). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(6):1595–606.

Mendes RE, Sader HS, Castanheira M, et al. Distribution of main gram-positive pathogens causing bloodstream infections in United States and European hospitals during the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (2010–2016): concomitant analysis of oritavancin in vitro activity. J Chemother. 2018;30(5):280–9.

Pfaller MA, Sader HS, Flamm RK, et al. Oritavancin in vitro activity against gram-positive organisms from European and United States medical centers: results from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program for 2010–2014. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;91(2):199–204.

Sweeney D, Stoneburner A, Shinabarger DL, et al. Comparative in vitro activity of oritavancin and other agents against vancomycin-susceptible and -resistant enterococci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(2):622–4.

Sweeney D, Shinabarger DL, Arhin FF, et al. Comparative in vitro activity of oritavancin and other agents against methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;87(2):121–8.

US National Institutes of Health. ClinicalTrials.gov identifer NCT03873987. 2021. http://clinicaltrials.gov/. Accessed 8 Dec 2021.

Deck DH, Jordan JM, Holland TL, et al. Single-dose oritavancin treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: SOLO trial efficacy by eron severity and management setting. Infect Dis Ther. 2016;5(3):353–61.

Corey GR, Good S, Jiang H, et al. Single-dose oritavancin versus 7–10 days of vancomycin in the treatment of gram-positive acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: the SOLO II noninferiority study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(2):254–62.

Corey GR, Kabler H, Mehra P, et al. Single-dose oritavancin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2180–90.

Lodise TP, Redell M, Armstrong SO, et al. Efficacy and safety of oritavancin relative to vancomycin for patients with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in the outpatient setting: results from the SOLO clinical trials. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(1):ofw274.

Corey GR, Loutit J, Moeck G, et al. Single intravenous dose of oritavancin for treatment of acute skin and skin structure infections caused by gram-positive bacteria: summary of safety analysis from the phase 3 SOLO studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(4):1–13.

Corey GR, Arhin FF, Wikler MA, et al. Pooled analysis of single-dose oritavancin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections caused by gram-positive pathogens, including a large patient subset with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48(5):528–34.

Syed YY, Scott LJ. Oritavancin: a review in acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. Drugs. 2015;75(16):1891–902.

García Robles AA, López Briz E, Fraga Fuentes MD, et al. Review of oritavancin for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. Farm Hosp. 2018;42(2):73–81.

Markham A. Oritavancin: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74(15):1823–8.

Redell M, Moeck G, Lucasti C, et al. A real-world patient registry for oritavancin demonstrates efficacy and safety consistent with the phase 3 SOLO program. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(6):ofy051.

Agarwal R, Bartsch SM, Kelly BJ, et al. Newer glycopeptide antibiotics for treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections: systematic review, network meta-analysis and cost analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(4):361–8.

Whittaker CA, Nhan E, Nguyen H, et al. Disease progression in patients with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: a comparative analysis between oritavancin and vancomycin [abstract no. 447]. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(Suppl 2):S220.

Lodise TP, Palazzolo C, Reksc K, et al. Comparisons of 30-day admission and 30-day total healthcare costs between patients who were treated with oritavancin or vancomycin for a skin infection in the outpatient setting. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(12):ofz475.

Jensen IS, Lodise TP, Fan W, et al. Use of oritavancin in acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections patients receiving intravenous antibiotics: a US hospital budget impact analysis. Clin Drug Investig. 2016;36(2):157–68.

Lodise TP, Fan W, Sulham KA. Economic impact of oritavancin for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections in the emergency department or observation setting: cost savings associated with avoidable hospitalizations. Clin Ther. 2016;38(1):136–48.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript was reviewed by: A. M. Casapao, College of Pharmacy, University of Florida, Jacksonville, FL, USA; J. Reilly, AtlantiCare Regional Medical Center, Pomona, NJ, USA. During the peer review process, Melinta Therapeutics, the marketing authorization holder of oritavancin, was also offered an opportunity to provide a scientific accuracy review of their data. Changes resulting from comments received were made on the basis of scientific and editorial merit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The preparation of this review was not supported by any external funding.

Authorship and conflict of interest

Young-A Heo, a salaried employee of Adis International Ltd/Springer Nature and an editor of Drugs & Therapy Perspectives, was not involved in any publishing decisions for the manuscript and declares no declare no relevant conflicts of interest. All authors contributed to the review and are responsible for the article content.

Ethics approval, consent to participate, consent for publication, availability of data and material, code availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

The original article has been revised due to retrospective open choice order.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heo, YA. Oritavancin (KIMYRSA™) in acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: a profile of its use in the USA. Drugs Ther Perspect 38, 57–63 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-021-00888-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-021-00888-1