Abstract

The list of approved indications for anakinra (Kineret®), an anti-interleukin (IL)-1 biological, has been expanded in the EU to include Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF). The pathology of FMF is associated with excess production of IL-1, thus IL-1 blockade with anakinra was investigated as a treatment for FMF. Results from a phase 3 clinical trial and real-world experience in patients with FMF demonstrated reductions in FMF attack frequency, improvements in quality of life and reductions in serum amyloid A (SAA) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. Efficacy was also observed in patients with FMF and amyloidosis in the real-world setting; nevertheless, concurrent use of colchicine with anti-IL-1 biologicals is recommended to prevent and/or halt the progression of amyloidosis. Anakinra was generally well tolerated during the phase 3 clinical trial, with comparable proportions of patients with adverse reactions in the anakinra and placebo groups. Furthermore, the safety profile of anakinra in FMF was consistent with that established in other indications, based on all available evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

IL-1 receptor antagonist that blocks inflammation induced by the inappropriate production of IL-1 in patients with FMF |

Decreases attack frequency, SAA and CRP levels, and improves quality of life in patients with FMF |

Generally well tolerated |

What is the rationale for using anakinra in familial Mediterranean fever (FMF)?

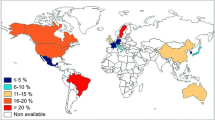

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is a rare hereditary condition that is associated with self-limiting bouts of fever and serosal inflammation [1]. The underlying pathology of FMF is attributed to mutations in the MEFV (Mediterranean fever) gene; some MEFV gene mutations are associated with the abnormal production of anti-interleukin (IL)-1β, which is responsible for the inflammatory symptoms of FMF. FMF is most common in Mediterranean populations, where the prevalence of FMF in these populations is 1 in 1000 to 1 in 400 people [1]. Globally, the prevalence of the five founder MEFV mutations (V726A, M694V, M694I, M680I and E148Q) is estimated to be 0–4.4% [2].

Colchicine is the current recommended first-line therapy for FMF, with the goal of treatment being to prevent FMF attacks and to reduce acute phase reactants, serum amyloid A (SAA) in particular [3]. Minimizing SAA levels that are elevated due to chronic inflammation is important in patients with FMF, as amyloidosis is a serious consequence of uncontrolled FMF and may result in renal failure [3]. Although colchicine is effective in most patients with FMF [4], a considerable proportion of patients continue to experience FMF attacks without achieving complete disease control [5]. The criteria for colchicine resistance are yet to be formally defined [3, 4]; however, it is agreed that additional treatments are required for patients with colchicine-resistant FMF [3, 4]. Additionally, 5–10% of patients experience gastrointestinal effects, particularly diarrhoea, with therapeutic dosages of colchicine [6]. Therefore, the use of biological treatment may be required for patients with colchicine-resistant FMF or patients who are intolerant to colchicine [3].

Anakinra is an IL-1 biological treatment that has been approved in the EU for the treatment of FMF (Table 1). Discussion of the use of anakinra in other approved indications, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [7, 8], cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) and Still's disease [9], is outside the scope of this review.

What is the pathogenesis of FMF and the mechanism of action of anakinra?

Anakinra is a recombinant human IL-1 receptor antagonist that inhibits binding of IL-1 to its receptor, and thereby prevents IL-1-mediated inflammation (Fig. 1). Mutations in the MEFV gene cause the production of mutant pyrin, which is associated with abnormal activation of the pyrin inflammasome [11]. Inflammasome activation results in the production of IL-1β, and the accompanying inflammation is responsible for the clinical signs of FMF attacks. Elevated levels of SAA are a consequence of chronic inflammation, which may lead to amyloidosis and renal damage [12]. IL-1 receptor blockade by anakinra prevents the binding of IL-1β to its receptor, thus preventing or reducing the severity of FMF attacks [12].

Pathology of familial Mediterranean fever, and mechanism of action of colchicine and anakinra [11]. IL interleukin, MEFV Mediterranean fever, SAA serum amyloid A

What are the pharmacokinetic properties of anakinra?

The pharmacokinetics (PK) of anakinra have been established in patients with other indications and in healthy subjects; PK studies were not conducted in patients with FMF [12]. The absolute bioavailability of anakinra is 95% in healthy subjects [10]. In patients with RA, maximum plasma concentrations are reached 3–7 h after administration of clinically relevant doses (1–2 mg/kg), with no noticeable distribution phase. The terminal half-life of anakinra is 4–6 h, and clearance increases with increasing creatinine clearance [10].

What is the efficacy of anakinra in FMF?

The efficacy of anakinra in reducing the frequency of FMF attacks was demonstrated in a pivotal, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial (Table 2) [13]. This trial included 25 patients aged ≥ 18 to ≤ 65 years who experienced at least one FMF attack per month in any of the four FMF sites (chest, abdomen, joints and skin). FMF in these patients was considered to be colchicine-resistant, as patients were receiving a maximum tolerated dosage of colchicine (≥ 2 to ≤ 3 mg/day), or were intolerant to colchicine ≥ 1.5 mg/day. Subcutaneous injections of anakinra 100 mg or placebo were self-administered daily for 4 months. Colchicine and other previous treatments were continued during the trial. [13].

The primary endpoint of the trial was the difference between anakinra and placebo in the total number of FMF attacks during the study period, adjusted to participation time (number of attacks per patient per month), as well as the difference between anakinra and placebo in the number of patients with a mean of < 1 FMF attack per month [13]. Both primary endpoints were met after 4 months of treatment; the mean frequency of FMF attacks in any site was significantly lower in patients treated with anakinra than in patients receiving placebo, and significantly more anakinra- than placebo-treated patients had < 1 FMF attack per month (Table 2). The mean frequency of joint attacks per month was significantly lower in the anakinra group than in the placebo group (p = 0.019); however, attack frequency in other sites (abdomen, chest and skin) did not differ significantly between treatment groups. Mean levels of inflammatory proteins [C-reactive protein (CRP) and SAA] were numerically lower (both p = 0.069) and mean quality of life (QoL) scores were significantly higher with anakinra relative to placebo (Table 2).

In a post hoc survival analysis, the mean time to reach the target of 4 FMF attacks was 89.8 days in the anakinra group and 39.6 days in the placebo group (p = 0.015). In another post hoc analysis, the proportion of patients who achieved improvement according to the modified FMF 50% improvement (FMF50) score was 83% with anakinra and 31% with placebo (p < 0.008). Modified FMF50 was defined as a ≥ 50% improvement in at least three of the four following categories: frequency of all FMF attacks, frequency of joint attacks, CRP or SAA levels (or normalization of these markers), and QoL score [13].

Real-world experience with anakinra and canakinumab (i.e. anti-IL-1 biological treatments) supports the efficacy results observed during the pivotal phase 3 trial (Table 3) [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Decreases in FMF attack frequency [14,15,16,17,18], CRP levels [14, 16, 17, 19], and/or reduction of disease activity [15,16,17, 19] were reported with anti-IL-1 treatment across six studies that each included ≥ 20 patients treated with anakinra (Table 3). Improvements were also reported across all 36-item short form survey (SF-36) QoL domains following anti-IL-1 treatment in one study (Table 3) [18].

Can anakinra be used in patients with FMF and amyloidosis/renal impairment?

Anakinra may be used in patients with FMF and amyloidosis or renal impairment; however, caution is recommended in patients with moderate renal impairment, and decreasing the frequency of treatment to once every 2 days should be considered in patients with severe renal impairment (Table 1) [10].

Anakinra was effective in patients with amyloidosis and various stages of renal impairment (including renal transplant patients) in a real-world study of 40 patients with FMF, 36 of whom were treated with anakinra [19]. Overall, anti-IL-1 therapy improved or stabilized renal function in 79.4% of patients, and decreased CRP levels and disease activity (Table 3). However, earlier stages of renal impairment may be more receptive to anti-IL-1 therapy. The beneficial effects of anti-IL-1 therapy on renal function were more pronounced in patients with a baseline creatinine level of < 1.5 mg/dL than in those with a baseline creatinine level of ≥ 1.5 mg/dL (Table 3) [19]. A similar trend was observed in a study of patients with colchicine-resistant FMF; only the subset of patients with a glomerular filtration rate of ≥ 60 mL/min/m2 experienced a significant improvement in proteinuria (Table 3) [16]. In other studies in patients with amyloidosis and FMF treated with anti-IL-1 therapy, organ failure was not observed (Table 3) [17] and, in another study, some SF-36 QoL domain scores improved in this subset of patients (Table 3) [18].

According to the EMA, there is insufficient evidence to support the efficacy of anakinra in the prevention of amyloidosis or improvement in renal function [12]. Concurrent treatment with colchicine is recommended (if appropriate) [12], as colchicine is an established treatment for the prevention of amyloidosis in FMF patients [3, 12].

Can anakinra be used on-demand?

On-demand treatment with anakinra was suitable for some patients based on real-world experience [20]; on-demand use of anakinra is not discussed in the EU prescribing information [10]. Patients with prominent prodromal signs or triggers, such as menstruation or long travel, may benefit most from on-demand treatment, as they may administer anakinra to prevent or reduce the severity of FMF attacks [20]. This approach may not be appropriate for all patients, particularly those with persistent inflammation, as the long-term effects of on-demand treatment are unknown [20].

On-demand anakinra treatment was effective in a real-world study in 15 patients, over a median of 6 months with on-demand therapy [20]. In the study, patients who were already receiving a maximum tolerated dose of colchicine were treated with on-demand anakinra for 2–3 days after experiencing a prodromal sign, or before and during exposure to an attack trigger (e.g. 5 consecutive days during menstruation). Patients also continued to take colchicine at the highest tolerated dose. Anakinra taken on-demand provided significant improvements from baseline in attack frequency (two vs four attacks per 3 months; p = 0.002), attack severity (6 vs 10 on a visual analogue scale; p = 0.001) and attack duration (1.5 vs 3 days; p = 0.001) in the total population. Additionally, by the end of the study, work absenteeism (2 vs 7 days per 3 months) and presenteeism (3.5 vs 9 days per 3 months) significantly (p = 0.002) improved in 14 working patients. CRP levels did not significantly change from baseline; however, the effect of on-demand treatment with anakinra on CRP levels is unknown, as patients with signs of persistent inflammation, proteinuria or amyloidosis were excluded. At the end of the study, 10 of 15 patients continued to be managed with on-demand anakinra, with five patients switching to continuous anakinra treatment [20].

On-demand anti-IL-1 therapy appeared to be effective in a study of young patients with FMF (mean age at treatment initiation 11.5 years) [21]. Of the 36 patients in this study, six patients were treated with on-demand anti-IL-1 therapy, including four patients with menstruation-triggered FMF. Anakinra was preferred for on-demand treatment over canakinumab in this study due to its shorter response time and half-life. In the four patients with menstruation-triggered FMF attacks, who were instructed to administer anakinra daily for 3 days from the first day of menstruation, no attacks were reported during 15 months of follow-up, and improvements in CRP levels and QoL were observed. The efficacy of on-demand treatment in the other two patients was not reported [21].

What is the tolerability profile of anakinra in FMF?

The safety profile of anakinra in FMF is consistent with its established safety profile in other indications, such as RA, Still’s disease and CAPS [10]. Overall, the most common (frequency ≥ 10%) adverse reactions associated with anakinra (regardless of indication) are increased blood cholesterol, headache and injection site reactions (ISRs) [10].

Anakinra 100 mg/day for 3 months was generally well tolerated in the pivotal phase 3 trial in 25 patients with colchicine-resistant FMF [13]. Drug-related adverse events (ISRs, headache, presyncope, dyspnoea and itching) were reported in 16.7% of patients in the anakinra group and 30.8% of patients in the placebo group. The proportion of patients with local ISRs was comparable between the anakinra and placebo groups (41.7% and 46.2%). Serious adverse events were not reported during the trial. All adverse events were mild or moderate in severity in both the anakinra and placebo groups [13].

Anti-IL-1 biologicals (including anakinra) had an acceptable safety profile in real-world studies in patients with FMF [14, 16, 17, 19]. In the largest dataset of patients receiving only anakinra (n = 106), ten patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events, including skin reactions (n = 5), leukopenia (n = 4), increased liver enzymes (n = 3) or ISRs (n = 2). All adverse events were reversible and resolved after discontinuation of treatment [15].

Anakinra may be associated with ISRs, which typically present as erythema, ecchymosis, inflammation and/or pain that develops within 2 weeks of initiating treatment and resolves within 4–6 weeks [10]. Recommendations should be followed to alleviate ISRs (Table 1). Other precautions should also be followed with regard to the risk of allergic reactions, infections and neutropenia (Table 1) [10].

What is the current clinical role of anakinra in FMF?

Anakinra is an effective treatment option in FMF, with reductions in frequency and severity of FMF attacks reported in patients with colchicine-resistant FMF in a phase 3 clinical trial (Table 2) and in the real-world setting (Table 3). The safety profile of anakinra has been established in other indications [10], and treatment was generally well tolerated in patients with FMF [13].

The two overarching objectives in EULAR guidelines for the treatment of FMF are to prevent FMF attacks and to minimize subclinical inflammation between attacks to prevent the progression of amyloidosis [3]. Guidelines recommend initiating treatment with colchicine as soon as FMF is diagnosed, and the addition of a biological treatment is recommended in patients who experience ≥ 1 attack per month for 6 months while receiving a maximally tolerated dosage of colchicine. While no particular biological treatment is recommended over others, EULAR guidelines suggest anti-IL-1 therapies in combination with colchicine are promising second-line treatment options [3]. As the most recent EULAR recommendations were published prior to the EU approvals of anakinra [10] and canakinumab [22], updated guidelines are awaited with interest.

First-line treatment with anakinra and colchicine may be justified in some patients, despite recommendations in current EULAR guidelines [3]. Colchicine is often ineffective in FMF patients with amyloidosis, and starting treatment with anti-IL-1 biologicals after colchicine failure may result in patients irreversibly losing the opportunity to benefit from biological therapy [23]. Real-world experience with anakinra supports this viewpoint, as the efficacy of anakinra was less pronounced in patients with renal insufficiency and/or amyloidosis (Table 3) [19].

To date, no randomized trials have directly compared the efficacy of anakinra with that of canakinumab, another biological anti-IL-1 therapy, in the treatment of FMF. In the absence of such trials, a preference for one treatment over another can only be based on indirect data. Economic factors may dictate treatment preference [24]. Differences in dosing frequency between anakinra and canakinumab may also influence treatment preference, as anakinra is administered daily [10], while canakinumab is administered once every 4 weeks [22]. Although the less frequent dosing of canakinumab is potentially more convenient to patients, the shorter duration of action of anakinra has been preferred for on-demand treatment [20]. Although data are limited, on-demand therapy with anakinra may be considered in patients with prominent prodromal signs or triggers and without signs of sustained inflammation [20]. Further research is required to determine the efficacy of on-demand anakinra treatment of FMF attacks.

Change history

04 February 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-021-00813-6

References

Alghamdi M. Familial Mediterranean fever, review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(8):1707–13.

Fujikura K. Global epidemiology of familial Mediterranean fever mutations using population exome sequences. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2015;3(4):272–82.

Ozen S, Demirkaya E, Erer B, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of familial Mediterranean fever. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(4):644–51.

Ozen S, Kone-Paut I, Gül A. Colchicine resistance and intolerance in familial Mediterranean fever: definition, causes, and alternative treatments. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47(1):115–20.

Gallizzi R, Bustaffa M, Mazza F, et al. Adherence to colchicine treatment and colchicine resistance in a multicentric FMF national cohort [abstract OP0273]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(Suppl 1):170–1.

Slobodnick A, Shah B, Pillinger MH, et al. Colchicine: old and new. Am J Med. 2015;128(5):461–70.

Waugh J, Perry CM. Anakinra: a review of its use in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. BioDrugs. 2005;19(3):189–202.

Cvetkovic RS, Keating G. Anakinra. BioDrugs. 2002;16(4):303–11.

Lyseng-Williamson KA. Anakinra in Still’s disease: a profile of its use. Drugs Ther Perspect. 2018;34(12):543–53.

Kineret (anakinra): summary of product characteristics. Stockholm: Swedish Orphan Biovitrum AB; 2020.

Schnappauf O, Chae JJ, Kastner DL, et al. The pyrin inflammasome in health and disease. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1745.

Kineret (anakinra): assessment report EMEA/H/C/000363/II/0070. Stockholm: Swedish Orphan Biovitrum AB; 2020.

Ben-Zvi I, Kukuy O, Giat E, et al. Anakinra for colchicine-resistant familial Mediterranean fever: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(4):854–62.

Akar S, Cetin P, Kalyoncu U, et al. Nationwide experience with off-label use of interleukin-1 targeting treatment in familial Mediterranean fever patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(7):1090–4.

Ugurlu S, Egeli BH, Ergezen B. Anakinra treatment in patients with familial Mediterranean fever: a single-center experience [abstract no. 2901]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(Suppl 10):5161–2.

Sahin A, Derin ME, Albayrak F, et al. Assessment of effectiveness of anakinra and canakinumab in patients with colchicine-resistant/unresponsive familial Mediterranean fever. Adv Rheumatol. 2020;60(1):12.

Kohler BM, Lorenz HM, Blank N. IL1-blocking therapy in colchicine-resistant familial Mediterranean fever. Eur J Rheumatol. 2018;5(4):230–4.

Varan O, Kucuk H, Babaoglu H, et al. Effect of interleukin-1 antagonists on the quality of life in familial Mediterranean fever patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(4):1125–30.

Ugurlu S, Ergezen B, Egeli BH, et al. Safety and efficacy of anti-interleukin-1 treatment in 40 patients, followed in a single centre, with AA amyloidosis secondary to familial Mediterranean fever. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa211.

Babaoglu H, Varan O, Kucuk H, et al. On demand use of anakinra for attacks of familial Mediterranean fever (FMF). Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(2):577–81.

Sag E, Akal F, Atalay E, et al. Anti-IL1 treatment in colchicine-resistant paediatric FMF patients: real life data from the HELIOS registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(11):3324–9.

Ilaris (canakinumab): summary of product characteristics. Dublin: Novartis Europharm Limited; 2019.

Tezcan ME. IL-1 blockers together with colchicine may be administered as first line therapy in familial Mediterranean fever with amyloidosis. Med Hypotheses. 2019;130:109269.

Hentgen V, Vinit C, Fayand A, et al. The use of interleukine-1 inhibitors in familial Mediterranean fever patients: a narrative review. Front Immunol. 2020;11:971.

Acknowledgements

The article was reviewed by: R. Dhouibi, Faculty of Medicine of Sfax, University of Sfax, Sfax, Tunisia; P.N.J. Langendijk, Department of Hospital Pharmacy, Reinier de Graaf Group Hospitals, Delft, Netherlands; B. Sozeri, Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, Health Sciences University, Istanbul, Turkey. During the peer review process, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum AB, the marketing-authorization holder of anakinra was also offered an opportunity to review this article. Changes resulting from comments received were made on the basis of scientific and editorial merit.

Funding

The preparation of this review was not supported by any external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authorship and Conflict of interest

A. Lee and H.A. Blair are salaried employees of Adis International Ltd/Springer Nature, and declare no relevant conflicts of interest. All authors contributed to the review and are responsible for the article content.

Ethics approval, Consent to participate, Consent to publish, Availability of data and material, Code availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Enhanced material for this Adis Drug Q&A can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13218803. |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, A., Blair, H.A. Anakinra in familial Mediterranean fever: a profile of its use. Drugs Ther Perspect 37, 101–107 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-020-00807-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-020-00807-w