Abstract

Background

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are largely used in older adults and data are needed in off-label indications, such as the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) in patients receiving oral anticoagulants (OACs). This study aimed to assess whether PPIs reduce the risk of UGIB in patients initiating oral anticoagulation.

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal study based on the French national health database. The study population included 109,693 patients aged 75–110 years with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation who initiated OACs [vitamin K antagonist (VKA) or direct OAC (DOAC)] between 2012 and 2016. We used multivariable Cox models weighted by inverse of probability of treatment to estimate the adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of UGIB between PPI users and nonusers over a 6- and 12-month follow-up.

Results

PPI users represented 23% of the study population (28% among VKA initiators and 17% among DOAC initiators). The mean age (83 ± 5.3 years) and proportion of women (near 60%) were similar between groups. The risk of UGIB in the first 6 months after initiation of OAC decreased by 20% in PPI users compared with PPI nonusers [aHR6 months = 0.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.65–0.98], but was not significantly modified when the follow-up was extended to 12 months (aHR12 months = 0.90, 95% CI 0.76–1.07), with a stronger effect among patients treated with vitamin K antagonists (aHR6 months = 0.73, 95% CI 0.58–0.93; aHR12 months = 0.81, 95% CI 0.67–0.99).

Conclusions

This study suggests that PPIs were associated with reduced risk of gastrointestinal bleeding after initiation of oral anticoagulation in older patients with atrial fibrillation, particularly within 6 months after initiation of an antivitamin K antagonist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Observational studies show that proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are often used off-label, particularly for preventing upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) in older patients treated with oral anticoagulants (OACs). Evidence is needed to support their use in this indication, as it could help reduce drug adverse events and health care costs. |

We compare the risk of UGIB between PPI users and nonusers among more than 100,000 French older adults with atrial fibrillation who initiated an OAC treatment between 2012 and 2016. |

The risk of UGIB decreased by 20% in the first 6 months after initiation of OAC in PPI users compared with PPI nonusers. The risk reduction was no longer significant when the follow-up was extended to 12 months. |

In subgroup analyses by type of OAC, the protective effects of PPIs persisted in vitamin k antagonist initiators but not in direct OAC initiators. |

1 Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs, such as pantoprazole, esomeprazole, omeprazole, lansoprazole, and rabeprazole) are drugs indicated for the treatment and prevention of peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux diseases [1]. The efficacy and safety of short-term use of PPIs, as well as the introduction of generics drugs, have contributed to the increase in PPI use over the past 2 decades [2]. However, misuse (inappropriate duration of use) and overuse of PPIs (prescription in the absence of validated indication) have been reported in many countries. In the UK, a quarter of PPI users were still treated 12 months after initiation [3]. In Ireland, long-term PPI use (≥ 8 weeks) in older adults increased from 4.1 to 35.5% between 1997 and 2012 [4]. In France, a study based on the French national health database showed that among more than 1.5 million adults aged 65 years or older who initiated a PPI in 2015, indication was off-label for 22.2% of them [5]. In addition to avoidable health care costs, PPIs misuse raises a safety issue, as adverse drug reactions have been reported for long-term use such as Clostridium difficile infection, community acquired pneumonia, hypomagnesia, vitamin B12 deficiency, fracture, and sarcopenia [6,7,8,9]. As a consequence, the prescription of PPIs for more than 8 weeks without justification was added to the criteria of potentially inappropriate prescriptions of the Beers and STOPP lists in 2015 [10, 11], hence reinforcing the need to rationalize PPI prescriptions in older adults.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia with 37.6 million people affected worldwide in 2017, with age being the main risk factor [12, 13]. OAC treatment for atrial fibrillation is a lifelong therapy with a high risk of bleeding, particularly in case of peptic ulcer disease [14]. Coprescription of PPIs with an oral anticoagulant (OAC) treatment for the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a frequent off-label indication for PPI use [5]. In France, data from the national health database indicated that 15% of PPI dispensing was related to the initiation of OAC or antiplatelet treatment in people aged over 65 years in 2015 [5]. Another French study conducted in a geriatrics ward in 2016–2017 also reported this indication as the main reason for off-label prescribing of PPIs [15]. Furthermore, an Irish study found that OAC or antiplatelet treatment was the main factor associated with long-term use and high dosage of PPI [4].

Although the prevention of UGIB in patients treated with OAC treatment is not a validated indication of PPIs, previous observational studies have suggested the added value of PPIs to prevent UGIB in this indication [16,17,18]. However, the Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulant Strategies (COMPASS) clinical trial did not confirm that pantoprazole could reduce the risk of UGIB in patients taking rivaroxaban and/or aspirin (HR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.67–1.15; mean age of study population: 67.6 ± 8.1 years) [19].

In 2020, the French National Health Authority (HAS) reviewed the indications of PPIs and considered that there may be a benefit to prescribe the PPIs with OACs to prevent UGIB in patients at risk of digestive complications, but further data were needed to support this indication [20]. In the context of massive utilization of PPIs in older adults and uncertainty of their benefit in coprescription with OACs, we aimed to conduct a large-scale study based on the data from the French national health database to assess whether prescribing a PPI in patients initiating an OAC for atrial fibrillation effectively decreased the risk of UGIB.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Sources

This study is based on the French national health database [Système National des Données de Santé (SNDS)], which has been widely used for epidemiological studies [21, 22], including for studies involving patients with atrial fibrillation initiating OACs [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. A complete description of the database is available in previous publications [30, 31]. Briefly, a unique anonymous individual identifier links information from the outpatient care database [DCIR (Données de Consommation Inter-Régime)] and hospital care database [PMSI (Programme de Médicalisation des Systèmes d’information)]. The DCIR database includes outpatient medical care reimbursement, including drugs coded according to the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification, status with respect to full reimbursement of care for a severe long-term disease, coded using the International Classification of Disease, tenth revision (ICD-10), as well as demographic information (age, sex, and date of death). The PMSI database includes all hospital diagnosis discharges, recorded using the ICD-10 classification, and medical procedures.

The data access permission policy prohibits making the data set publicly available.

2.2 Study Population

We conducted a longitudinal study on patients aged 75–110 years old, diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, and initiating an OAC treatment (no dispensing in the previous 2 years), either vitamin-K antagonist (VKA) or direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), between April 2012 and 2016 (inclusion date). The 75-year threshold used to define our study population was defined in line with previous studies and recommendations concerning medication use in older people in France [32,33,34]. We restricted the study population to people affiliated with the French general health insurance scheme for at least 5 years at inclusion so that we could assess medical history. Atrial fibrillation was defined according to previous studies conducted on the SNDS (see Supplementary Methods for definition) [23,24,25, 28, 29]. Patients with contraindications to the use of OACs were excluded (see Supplementary Methods for exclusion criteria). In addition, patients who had received a PPI within 3 months prior to OAC initiation were excluded.

2.3 Exposure and Outcome Definitions

The exposure to PPI was defined as the reimbursement of at least one of the following ATC codes within the 14 days following inclusion: A02BC05, A02BC03, A02BC01, A02BC02, or A02BC04.

The outcome event was the occurrence of hospitalization for UGIB according to the following ICD-10 codes during the follow-up period (any diagnostic position in the hospital record): K250, K52, K254, K256, K260, K262, K264, K266, K270, K272, K274, K276, K280, K282, K284, K286, K290, K920, K921, or I850 (see Supplementary Table 1 for details about the codes). Melena has an upper gastrointestinal predominant origin, but it can also have a lower origin. To reduce the risk of identifying cases of lower gastrointestinal origin, we considered the diagnosis code K921 in the outcome definition unless the diagnosis code K625 (anus or rectum bleeding) was also recorded for the same hospitalization.

2.4 Covariates

Covariates assessed at baseline included sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, and quintile of deprivation index—a combination of four socioeconomic variables at the smallest administrative unit in France), 5-year medical history (cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, epilepsy or psychiatric diseases, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, cancer, coagulation abnormalities, and hemorrhage), and drug exposure in the 4 months before inclusion (antihypertensive drugs, lipid-lowering agents, oral corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, anxiolytics and hypnotics, and analgesics). Concomitant dispensing of drugs that increase the risk of bleeding, namely nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, heparin and antiplatelet agent, and the total number of different ATC codes (0–4/5 to 9/10 drugs or more) at OAC initiation were also considered. The individual risk of bleeding was assessed using a version of the HAS-BLED score adapted for use in the French national health database [28].

2.5 Follow-Up

In PPI users, the follow-up started on the first date of PPI dispensing within the 14-day period following OAC initiation (index date). This time window was chosen to include patients who had been prescribed a PPI by another physician in the days following OAC initiation. In PPI nonusers, the index date was randomly defined over this 14-day period so that the distribution of time between OAC initiation and index date was similar between PPI users and nonusers.

Patients were followed for 12 months or until the occurrence of UGIB, death, discontinuation of OAC treatment (defined as at least 3 months without OAC dispensing), or switch from a VKA to a DOAC and vice-versa (only for analyses by type of OAC), whichever came first. The time scale was time since start of follow-up (in days).

2.6 Analyses

Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) of UGIB between PPI users and nonusers. Different models have been implemented to progressively control for confounding and indication bias: a first model without adjustment to assess the crude association, a second model adjusted for confounders by multivariable Cox regression, and a final and main model controlling for indication bias by inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) adjustment, including weight stabilization [35, 36]. All above mentioned covariates were used for adjustment. The distribution of stabilized weights was analyzed to test the positivity assumption [35]. The balance of covariates between the PPI users and nonusers before and after weighting was assessed by measuring the standardized mean difference. We conducted two parallel analyses, the first with an end of follow-up at 6 months, at the latest, and the second at 12 months. We explored two end-of-follow-up periods, as the risk of bleeding is higher at OAC treatment initiation, especially for VKA, which may require dosage adjustment. In addition, the HR estimate is a weighted average of all instantaneous risks over the study period. Estimating the HR over a shorter period allow us to test for potential variation of the effect over time [37].

In addition to the semiparametric approach of the Cox model, Kaplan–Meier cumulative incidence curves of UGIB adjusted for IPTW were also estimated [38, 39]. Bootstraping based on the standard deviation method was used to calculate the 95% confidence interval (200 replications).

To assess the effect of PPIs by sociodemographic variables and risk of UGIB, we repeated the 6-month analysis in the following subgroups: sex, age categories (75–89 years and ≥ 90 years), HAS-BLED score (score 1 to 2 and score ≥ 3), year of inclusion, and exposition to an antiplatelet agent at baseline.

Several sensitivity analyses were performed. First, we introduced an additional censoring event at PPI discontinuation in the exposed group and at PPI initiation in the unexposed group. In this analysis, we additionally weighted by the inverse of the probability of censoring for PPI discontinuation or initiation, respectively (IPTCW), using all baseline covariates and spline terms for modeling time trends in censuring [40, 41]. Second, to assess the specificity of the effect of PPIs on UGIB, analyses were repeated with nongastrointestinal bleeding as the outcome. The ICD-10 codes used to define nongastrointestinal bleeding are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. Other sensitivity analyses included: (1) defining PPI use based on the drugs dispensed on the same day as OAC initiation (versus within 14 days in the main analysis), (2) excluding patients with at least one PPI dispensation within 6 months before inclusion (versus 3 months in the main analysis), and (3) considering death as a competing risk to estimate the cumulative incidence curves and the risk for UGIB.

Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Inc).

3 Results

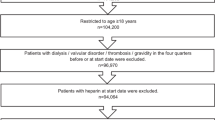

The selection of the study population is shown in Fig. 1. Between April 2012 and December 2016, 196,275 individuals aged 75–110 years affiliated with the general schemes and with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation initiated an OAC treatment. Among them, we excluded 18,824 individuals who had a contraindication to OAC use and an additional 67,585 individuals who received at least one PPI dispensation in the 3 months before OAC initiation. In the end, the study population included 109,693 subjects. Of these, 53.6% initiated a VKA (mostly fluindione) and 46.4% a DOAC (mostly rivaroxaban; see Supplementary Table 2 for the details of the OACs).

As described in Table 1, PPI users represented 23% of the study population (28% among VKA initiators and 17% among DOAC initiators). The mean age (83 ± 5.3 years) and proportion of women (near 60%) were similar between PPI users and nonusers. Overall, PPI users had chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, more frequently than PPI nonusers, particularly among VKA initiators. PPI users had a higher risk of bleeding according to the HAS-BLED score and were more exposed to antiplatelet agents (28% of PPI users and 10% of PPI nonusers) at OAC initiation (see Supplementary Table 3 for information on prior treatments). The mean duration of follow-up for PPI users was 266 ± 123 days and 284 ± 117 days for PPI nonusers (see Supplementary Table 4 for information on follow-up duration and censoring events).

Cumulative incidence curves adjusted for IPTW show that the incidence of UGIB was slightly lower in PPI users compared with PPI nonusers (Fig. 2), with a greater difference in VKA initiators than in DOAC initiators. Table 2 presents the number of events, crude incidence of UGIB, and its association with PPI exposure. During the 12-month follow-up 1141 UGIB events occurred, of which two-thirds occurred during the first 6 months. The unadjusted Cox model showed an increased risk of UGIB in PPI users compared with PPI nonusers, regardless of the duration of follow-up and type of OAC. After adjustment for the covariates, the association was reversed: PPI use was associated with a significantly lower risk of UGIB in the 6 months after OAC initiation (aHR6 months = 0.82, 95% CI 0.69–0.98), with no significant effect when follow-up ended at 12 months. Weighting on IPTW enabled to balance the covariates frequency between PPI users and nonusers (see Supplementary Fig. 1). In the Cox model with IPTW, PPI use remained associated with a lower risk of UGIB in the 6-month follow-up analysis (aHR6 months = 0.80, 95% CI 0.65–0.98), without significant effect in the 12-month follow-up analysis (aHR12 months = 0.90, 95% CI 0.76–1.07). The risk of UGIB was significantly decreased in VKA initiators (aHR6 months = 0.73, 95% CI 0.58–0.93; aHR12 months = 0.81, 95% CI 0.67–0.99) but not in DOAC initiators (aHR6 months = 0.89, 95% CI 0.59–1.33; aHR12 months = 0.93, 95% CI 0.67–1.30). No association was found between PPI use and other bleeding events.

Adjusted cumulative incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) over 12 months by proton pump inhibitor (PPI) exposure group in patients with atrial fibrillation initiating an oral anticoagulant, either vitamin K antagonist or direct oral anticoagulant; results adjusted for the inverse of probability of treatment weighting [French national health database (SNDS), France]

Subgroup analyses are shown in Fig. 3. Of note, there was no difference in the risk of UGIB according to age category (75–89 years versus 90 years and over), bleeding risk assessed with the HAS-BLED score, and use of APT.

Association between proton pomp inhibitor (PPI) use and risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) over 6 months in patients with atrial fibrillation initiating an oral anticoagulant treatment, subgroup analyses [French national health database (SNDS), France]. NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. NSAIDs and antiplatelet agent exposure is considered at inclusion and four months before

The results of the sensitivity analyses are described in Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 2. Briefly, estimations resulting from IPTCW were consistent with the main analysis, although slightly attenuated. The decrease in the risk of UGIB was greater when exposure was defined as PPI dispensing on the same date of the first OAC dispensing, except for DOAC initiators. Conversely, the exclusion of PPI users within the 6 months before the initiation of OAC lessened the associations. Finally, the calculated associations were significant when death was considered as a competing risk to estimate the cumulative incidence curves.

4 Discussion

This longitudinal study based on the French national health database investigated the added value of PPIs to prevent UGIB in 109,693 patients aged 75–110 years with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulation between 2012 and 2016. We report a 20% relative risk reduction of UGIB among PPI users compared with PPI nonusers in the first 6 months after OAC initiation, which did not persist when the follow-up was extended to 12 months. When the type of anticoagulation was differentiated, the risk reduction was more important in patients treated with VKA (53.6% of the study population) than in patients receiving DOAC.

The lower risk of UGIB among PPI users initiating an OAC reported in our study is consistent with results of previous observational studies, although greater effects have been previously reported [42, 43]. Indeed, two recent meta-analyses, including seven and ten studies, reported a 32–33% decrease in the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with PPI in OAC users [42, 43]. The study by Ray et al. contributed the most to these results as it was the largest study; based on the Medicare database, they estimated that PPI use decreased the risk of UGIB by 32% (aIRR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.62–0.69) in patients treated with OAC for atrial fibrillation [17]. Furthermore, the specificity of our results is supported by the lack of association with nongastrointestinal bleeding events.

Although our study reports a reduced risk of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with PPI use in VKA initiators [17, 18, 43, 44], it did not confirm the risk reduction observed in previous studies among DOAC initiators [16,17,18, 43, 45]. This result is surprising, as the meta-analysis by Anh et al. reported little difference in the risk of UGIB according to the type of OAC; OR = 0.65 (95% CI 0.62–0.69) for warfarin, OR = 0.67 (95% CI 0.56–0.81) for apixaban, OR = 0.56 (95% CI 0.45–0.69) for dabigatran, and OR = 0.76 (95% CI 0.62–0.91) for rivaroxaban [43]. In addition, using pooled data from Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands, Komen et al. estimated that the risk of UGIB was 25% lower (IRRa = 0.75, 95% CI 0.59–0.95) when DOAC were prescribed with PPIs [16]. In our study, power issues could have contributed to the absence of significant results in the subgroup analyses. In the study by Komen et al., the risk of UGIB became nonsignificant in Sweden and in the Netherlands when the analysis was stratified by country [16]. The hypothesis of a higher risk of bleeding with VKAs compared with DOACs could also explain why the protective effect of PPIs was observed in VKA users only. However, this difference in bleeding risk between VKAs and DOACs remains debated [24, 46,47,48]. Difference in the characteristics of patients treated with VKAs and DOACs may also explain part of the difference in the results between the types of OAC in our study. Indeed, VKA initiators were older and more at risk of bleeding according to HAS-BLED score. They also had more cardiovascular disease and heavier medication than DOAC initiators. As the study period corresponded to the beginning of commercialization of DOACs in France, VKAs may have been preferred to DOACs for patients with poorer health status because they were better known to prescribers.

In its 2020 reevaluation of PPIs, the HAS mentioned the potential benefit of PPIs in combination with oral anticoagulation in patients at risk of digestive complications [20]. Indeed, Ray et al. reported a protective association between PPI use and the risk of UGIB, the magnitude of which increased with the bleeding risk score [17]. However, we did not observe significant difference in the risk of UGIB according to age, APT use, and HAS-BLED score in our study. The lack of association with this usual risk factor may be due to the selection of relatively older people (of mean age 83 years versus 76 years in the study by Ray et al. [17]) with no history of gastrointestinal bleeding in the last 12 months. In addition, the HAS-BLED score may be underestimated in our study, as there is no information on the measurement of the International Normalized Ratio in administrative databases.

Our study focused on the risk of UGIB during the first 12 months after the initiation of the ACO. The fact that PPI prescribing was associated with a risk reduction of UGIB in the first 6 months of follow-up and not after could indicate a mitigation of the effect of PPIs with time. However, it could also be explained by possible discontinuation of PPI treatment over time, but the sensitivity analysis with censoring at PPI discontinuation provided similar results. Finally, it could also be due to the depletion of susceptible over time, where the proportion of patients who are likely to develop UGIB decreases faster in PPI nonusers than in PPI users [37, 49].

The use of the SNDS allowed us to include over 100,000 patients with atrial fibrillation starting an OAC treatment over nearly 5 years and to observe the occurrence of UGIB, which is a rare but severe event. However, our study has several limitations. First, the use of claims data only accounts for drugs that are reimbursed; therefore, self-medication of PPIs could not be considered, although they have been available without prescription since 2010 in France. However, this probably had a limited effect on our results, since 97% of PPIs were prescribed in 2015 [5]. Second, some information was unknown, such as indication of treatments, compliance or the exact dose received. Finally, the use of healthcare administrative data may lead to potential residual confounding as information on some potential confounders, such as smoking, alcohol use, and ulcers, was not available in this study.

In conclusion, this study suggests that PPIs were associated with reduced risk of gastrointestinal bleeding after initiation of oral anticoagulation in older patients with atrial fibrillation, particularly within 6 months after initiation of antivitamin K antagonist. The greater effect with VKAs and the optimal duration of PPI treatment need further study. And, as the potentially inappropriate medication criteria remind us, caution is still required regarding the long-term use of PPIs.

References

Shin JM, Sachs G. Pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:528–34.

Lanas A. We are using too many ppis, and we need to stop: a European perspective. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol ACG. 2016;111:1085–6.

Othman F, Card TR, Crooks CJ. Proton pump inhibitor prescribing patterns in the UK: a primary care database study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25:1079–87.

Moriarty F, Bennett K, Cahir C, et al. Characterizing potentially inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in older people in primary care in Ireland from 1997 to 2012. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:e291–6.

Lassalle M, Le Tri T, Bardou M, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors in adults in France: a nationwide drug utilization study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76:449–57.

Salvo EM, Ferko NC, Cash SB, et al. Umbrella review of 42 systematic reviews with meta-analyses: the safety of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54:129–43.

Jaynes M, Kumar AB. The risks of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: a critical review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098618809927.

Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008;336:2–3.

Maes ML, Fixen DR, Linnebur SA. Adverse effects of proton-pump inhibitor use in older adults: a review of the evidence. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2017;8:273–97.

The 2015 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® update expert panel. American Geriatrics Society. updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;2015(63):2227–46.

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44:213–8.

Wang L, Ze F, Li J, et al. Trends of global burden of atrial fibrillation/flutter from Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Heart. 2021;107:881–7.

Kornej J, Börschel CS, Benjamin EJ, et al. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in the 21st century. Circ Res. 2020;127:4–20.

Shoeb M, Fang MC. Assessing bleeding risk in patients taking anticoagulants. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013;35:312–9.

Michelon H, Delahaye A, Fellous L, et al. Proton pump inhibitors: why this gap between guidelines and prescribing practices in geriatrics? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;75:1327–9.

Komen J, Pottegård A, Hjemdahl P, et al. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, proton pump inhibitors and gastrointestinal bleeds. Heart. 2022;108:613–8.

Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Association of oral anticoagulants and proton pump inhibitor cotherapy with hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. JAMA. 2018;320:2221.

Lee S-R, Kwon S, Choi E-K, et al. Proton pump inhibitor co-therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with oral anticoagulants and a prior history of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2022;36:679–89.

Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, et al. Pantoprazole to prevent gastroduodenal events in patients receiving rivaroxaban and/or aspirin in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:403-412.e5.

Commission de la Transparence. Rapport d’évaluation Des Inhibiteurs de La Pompe à Protons (Spécialités et Génériques). Haute Autorité de Santé. 2020:163.

Semenzato BJ, Drouin J, et al. Antihypertensive drugs and COVID-19 risk. Hypertension. 2021;77:833–42.

Penso L, Dray-Spira R, Weill A, et al. Association between biologics use and risk of serious infection in patients with psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1056.

Billionnet C, Alla F, Bérigaud É, et al. Identifying atrial fibrillation in outpatients initiating oral anticoagulants based on medico-administrative data: results from the French national healthcare databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:535–43.

Maura G, Blotière P-O, Bouillon K, et al. Comparison of the short-term risk of bleeding and arterial thromboembolic events in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients newly treated with dabigatran or rivaroxaban versus vitamin K antagonists: a French nationwide propensity-matched cohort study. Circulation. 2015;132:1252–60.

Maura G, Pariente A, Alla F, et al. Adherence with direct oral anticoagulants in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation new users and associated factors: a French nationwide cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:1367–77.

Maura G, Billionnet C, Alla F, et al. Comparison of treatment persistence with dabigatran or rivaroxaban versus vitamin k antagonist oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation patients: a competing risk analysis in the french national health care databases. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38:6–18.

Neumann A, Jabagi M-J, Zureik M. Vitamin K antagonists did not increase the risk of myelodysplastic syndrome in a large-scale cohort study. Blood. 2021;138:417–20.

Maura G, Bardou M, Billionnet C, et al. Oral anticoagulants and risk of acute liver injury in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a propensity-weighted nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:11624.

Maura G, Billionnet C, Drouin J, et al. Oral anticoagulation therapy use in patients with atrial fibrillation after the introduction of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: findings from the French healthcare databases, 2011–2016. BMJ Open. 2019;9: e026645.

Bezin J, Duong M, Lassalle R, et al. The national healthcare system claims databases in France, SNIIRAM and EGB: Powerful tools for pharmacoepidemiology. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:954–62.

Tuppin P, Rudant J, Constantinou P, et al. Value of a national administrative database to guide public decisions: from the système national d’information interrégimes de l’Assurance Maladie (SNIIRAM) to the système national des données de santé (SNDS) in France. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2017;65:S149–67.

Laroche M-L, Charmes J-P, Merle L. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: a French consensus panel list. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:725–31.

Bongue B, Laroche ML, Gutton S, et al. Potentially inappropriate drug prescription in the elderly in France: a population-based study from the French National Insurance Healthcare system. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:1291–9.

Roux B, Berthou-Contreras J, Beuscart J-B, et al. REview of potentially inappropriate MEDIcation pr[e]scribing in Seniors (REMEDI[e]S): French implicit and explicit criteria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77:1713–24.

Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34:3661–79.

Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:656–64.

Hernán MA. The hazards of hazard ratios. Epidemiology. 2010;21:13–5.

Cole SR, Hernán MA. Adjusted survival curves with inverse probability weights. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2004;75:45–9.

Neumann A, Billionnet C. Covariate adjustment of cumulative incidence functions for competing risks data using inverse probability of treatment weighting. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;129:63–70.

Robins JM, Finkelstein DM. Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS Clinical Trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics. 2000;56:779–88.

Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman JH. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2009. (Corrected 7th printing).

Kurlander JE, Barnes GD, Fisher A, et al. Association of antisecretory drugs with upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients using oral anticoagulants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2022;135:1231-1243.e8.

Ahn H, Lee S, Choi E, et al. Protective effect of proton-pump inhibitor against gastrointestinal bleeding in patients receiving oral anticoagulants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:4676–87.

Bang CS, Joo MK, Kim B-W, et al. The role of acid suppressants in the prevention of anticoagulant-related gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Liver. 2020;14:57–66.

Dong Y, He S, Li X, et al. Prevention of non-vitamin k oral anticoagulants-related gastrointestinal bleeding with acid suppressants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Appl Thromb. 2022;28:10760296211064896.

Burr N, Lummis K, Sood R, et al. Risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with direct oral anticoagulants: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:85–93.

He Y, Wong ICK, Li X, et al. The association between non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82:285–300.

Lip GYH, Keshishian AV, Zhang Y, et al. Oral anticoagulants for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in patients with high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4: e2120064.

Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Brenner B, et al. Bias from depletion of susceptibles: the example of hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:554–60.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Géric Maura, Cécile Billionnet, and Jérôme Drouin for their previous work, in particular, for the elaboration of numerous definitions used to identify the study population and to calculate the covariates, and for providing part of the data used in our analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SD, AN, HM, MP, MZ, and MH have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Funding sources

This work was conducted at EPI-PHARE and University of Paris-Saclay, UVSQ and supported by the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety [Grant no. 2019S008] within the scope of Ph.D. funding to S.D.

Sponsor’s role

The French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Availability of data and materials

In accordance with data protection legislation and French regulations, the authors cannot publicly release data from the French National Health Data System (SNDS). However, any person or structure, public or private, for-profit or nonprofit, is entitled to access SNDS data upon authorization from the French Data Protection Office (CNIL), for the purposes of carrying out a study, research, or an evaluation in the public interest (https://www.snds.gouv.fr/SNDS/Processus-d-acces-aux-donnees and https://www.indsante.fr/). EPI-PHARE has permanent regulatory access to data from the French National Health Data System (SNDS) via its constitutive bodies ANSM and CNAM. This permanent access is given in accordance with French Decree no. 2016-1871 of 26 December 2016 relating to personal data processing under the French National Health Data System (SNDS) and French law articles Art. R. 1461-13 and 14. All requests in the database were made by duly authorized people. In accordance with the permanent regulatory access granted to EPI-PHARE via ANSM and CNAM, this work did not require the approval of the French Data Protection Authority (CNIL). The study was registered on the study register of EPI-PHARE for studies based on SNDS data (T-2021-10-340).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been authorized and conducted according to decree 2016–1871 of 26 December 2016 relating to personal data processing under the French National Health Data System (SNDS) and French law articles Art. R. 1461–1323 and 1424(5). As permanent users of the SNDS, the author’s team is exempted from institutional review board approval. Given that data are anonymous, informed consent to participate was not required.

Authors’ contributions

This study is a part of the PhD thesis of S.D. and supervised by M.H. and M.Z. M.H. and M.Z. conceptualized the study. M.H., M.Z., H.M., M.P., and S.D. designed the methodology, S.D. and A.N. extracted and managed the data, S.D. performed the analyses under the supervision of A.N. and M.H. S.D. wrote the manuscript and M.H., H.M., A.N., M.P., and M.Z. reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.Z., S.D.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Drusch, S., Neumann, A., Michelon, H. et al. Do Proton Pump Inhibitors Reduce Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Older Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Treated with Oral Anticoagulants? A Nationwide Cohort Study in France. Drugs Aging 41, 65–76 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-023-01085-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-023-01085-7