Abstract

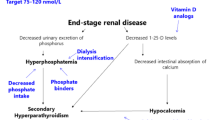

Hyperphosphataemia can be induced by three main conditions: a massive acute phosphate load, a primary increase in renal phosphate reabsorption, and an impaired renal phosphate excretion due to acute or chronic renal insufficiency. Renal excretion is so efficient in normal subjects that balance can be maintained with only a minimal rise in serum phosphorus concentration even for a large phosphorus load. Therefore, acute hyperphosphataemia usually resolves within few hours if renal function is intact. The most frequent cause of chronic hyperphosphataemia is chronic renal failure. Hyperphosphataemia in chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Lowering the phosphate load and maintaining serum phosphorus levels within the normal range are considered important therapeutic goals to improve clinical outcomes in CKD patients. Treatment consists of diminishing intestinal phosphate absorption by a low phosphate diet and phosphate binders. In CKD patients on dialysis an efficient dialysis removal of phosphate should be ensured. Dietary restriction of phosphorus while maintaining adequate protein intake is not sufficient to control serum phosphate levels in most CKD patients; therefore, the prescription of a phosphate binder is required. Aluminium-containing agents are efficient but no longer widely used because of their toxicity. Calcium-based salts are inexpensive, effective and most widely used, but there is now concern about their association with hypercalcaemia, parathyroid gland suppression, adynamic bone disease, and vascular and extraosseous calcification. The average daily dose of calcium acetate or carbonate prescribed in the randomised controlled trials to control hyperphosphataemia in dialysis patients ranges between 1.2 and 2.3 g of elemental calcium. Such doses are greater than the recommended dietary calcium intake and can lead to a positive calcium balance. Although large amounts of calcium salts should probably be avoided, modest doses (<1 g of elemental calcium) may represent a reasonable initial approach to reduced serum phosphorus levels. A non-calcium-based binder can then be added when large doses of binder are required. At present, there are three types of non-calcium-based phosphate binders available: sevelamer, lanthanum carbonate and magnesium salts. Each of these compounds is as effective as calcium salts in lowering serum phosphorus levels depending on an adequate prescribed dose and adherence of the patient to treatment. Sevelamer is the only non-calcium-containing phosphate binder that does not have potential for systemic accumulation and presents pleiotropic effects that may impact on cardiovascular disease. In contrast, lanthanum carbonate and magnesium salts are absorbed in the gut and their route of excretion is biliary for lanthanum and urinary for magnesium. There are insufficient data to establish the comparative superiority of non-calcium binding agents over calcium salts for such important patient-level outcomes as all-cause mortality and cardiovascular end points. Moreover, full adoption of sevelamer and lanthanum by government drug reimbursement agencies in place of calcium salts would lead to a large increase in health-care expenditure. Therefore, the choice of phosphate binder should be individualised, considering the clinical context, the costs, and the individual tolerability the concomitant effects on other parameters of mineral metabolism, such as serum calcium and parathyroid hormone, besides those on serum phosphorus.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Marks J, Debnam ES, Unwin RJ. Phosphate homeostasis and the renal–gastrointestinal axis. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2010;299:F285–96.

Sabbagh Y, Giral H, Caldas Y, et al. Intestinal phosphate transport. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18:85–90.

Uribarri J. Phosphorus homeostasis in normal health and in chronic kidney disease patients with special emphasis on dietary phosphorus intake. Semin Dial. 2007;20:295–301.

Gutierrez OM, Wolf M. Dietary phosphorus restriction in advanced chronic kidney disease: merits, challenges, and emerging strategies. Semin Dial. 2010;23:401–6.

Murer H, Lötscher M, Kaissling B, et al. Renal brush border membrane Na/Pi-cotransport: molecular aspects in PTH-dependent and dietary regulation. Kidney Int. 1996;49:1769–73.

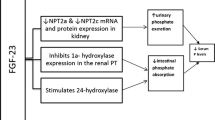

Gattineni J, Bates C, Twombley K, et al. FGF23 decreases renal NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c expression and induces hypophosphatemia in vivo predominantly via FGF receptor 1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F282–91.

Bergwitz C, Juppner H. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by PTH, vitamin D, and FGF23. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:91–100.

Ferrari SL, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R. Fibroblast growth factor-23 relationship to dietary phosphate and renal phosphate handling in healthy young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1519–24.

Burnett SM, Gunawardene SC, Bringhurst FR, et al. Regulation of C-terminal and intact FGF-23 by dietary phosphate in men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1187–96.

Antoniucci DM, Yamashita T, Portale AA. Dietary phosphorus regulates serum fibroblast growth factor-23 concentrations in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3144–9.

Riminucci M, Collins MT, Fedarko NS, et al. FGF-23 in fibrous dysplasia of bone and its relationship to renal phosphate wasting. J Clin Investig. 2003;112:683–92.

Beloosesky Y, Grinblat J, Weiss A, et al. Electrolyte disorders following oral sodium phosphate administration for bowel cleansing in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:803–8.

Curran MP, Plosker GL. Oral sodium phosphate solution: a review of its use as a colorectal cleanser. Drugs. 2004;64:1697–714.

Casais MN, Rosa-Diez G, Pérez S, et al. Hyperphosphatemia after sodium phosphate laxatives in low risk patients: prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5960–5.

Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, Radhakrishnan J, et al. Acute phosphate nephropathy following oral sodium phosphate bowel purgative: an underrecognized cause of chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3389–96.

Ori Y, Rozen-Zvi B, Chagnac A, et al. Fatalities and severe metabolic disorders associated with the use of sodium phosphate enemas: a single center’s experience. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:263–5.

Arrambide K, Toto RD. Tumor lysis syndrome. Semin Nephrol. 1993;13:273–80.

Llach F, Felsenfeld AJ, Haussler MR. The pathophysiology of altered calcium metabolism in rhabdomyolysis-induced acute renal failure. Interactions of parathyroid hormone, 25-hydroxycholecalciferol, and 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:117–23.

Kebler R, McDonald FD, Cadnapaphornchai P. Dynamic changes in serum phosphorus levels in diabetic ketoacidosis. Am J Med. 1985;79:571–6.

Collins MT, Lindsay JR, Jain A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 is regulated by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1944–50.

Quigley R, Baum M. Effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I on rabbit proximal convoluted tubule transport. J Clin Investig. 1991;88:368–74.

Mitnick PD, Goldfarb S, Slatopolsky E, et al. Calcium and phosphate metabolism in tumoral calcinosis. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92:482–7.

Topaz O, Shurman DL, Bergman R, et al. Mutations in GALNT3, encoding a protein involved in O-linked glycosylation, cause familial tumoral calcinosis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:579–81.

Chefetz I, Heller R, Galli-Tsinopoulou A, et al. A novel homozygous missense mutation in FGF23 causes Familial Tumoral Calcinosis associated with disseminated visceral calcification. Hum Genet. 2005;118:261–6.

Araya K, Fukumoto S, Backenroth R, et al. A novel mutation in fibroblast growth factor 23 gene as a cause of tumoral calcinosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5523–37.

Ichikawa S, Imel EA, Kreiter ML, et al. A homozygous missense mutation in human KLOTHO causes severe tumoral calcinosis. J Clin Investig. 2007;117:2684–91.

Kurosu H, Ogawa Y, Miyoshi M, et al. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6120–3.

Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, et al. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006;444:770–4.

Slavin RE, Wen J, Kumar D, et al. Familial tumoral calcinosis. A clinical, histopathologic, and ultrastructural study with an analysis of its calcifying process and pathogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:788–802.

Wolf M. Update on fibroblast growth factor 23 in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2012;89:737–47.

Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1370–8.

Larner AJ. Pseudohyperphosphatemia. Clin Biochem. 1995;28:391–3.

Lane JW, Rehak NN, Hortin GL, et al. Pseudohyperphosphatemia associated with high-dose liposomal amphotericin B therapy. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;387:145–9.

Schiller B, Virk B, Blair M, et al. Spurious hyperphosphatemia in patients on hemodialysis with catheters. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:617–20.

Ball CL, Tobler K, Ross BC, et al. Spurious hyperphosphatemia due to sample contamination with heparinized saline from an indwelling catheter. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42:107–8.

Yamaguchi T, Sugimoto T, Imai Y, et al. Successful treatment of hyperphosphatemic tumoral calcinosis with long-term acetazolamide. Bone. 1995;16:247S–50S.

Slatopolsky E, Brown A, Dusso A. Role of phosphorus in the pathogenesis of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37(Suppl 2):S54–7.

Mathew S, Tustison KS, Sugatani T, Chaudhary LR, Rifas L, Hruska KA. The mechanism of phosphorus as a cardiovascular risk factor in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1092–105.

Kestenbaum B, Sampson JN, Rudser KD, Patterson DJ, Seliger SL, Young B, Sherrard DJ, Andress DL. Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:520–8.

Voormolen N, Noordzij M, Grootendorst DC, et al. High plasma phosphate as a risk factor for decline in renal function and mortality in pre-dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2909–16.

Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM, Ofsthun N, Lowrie EG, Chertow GM. Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2208–18.

Hruska KA, Teitelbaum SL. Mechanisms of disease: renal osteodystrophy. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:166–75.

Disease Kidney, Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int. 2009;76(Suppl 113):S1–130.

Isakova T, Gutierrez OM, Chang Y, Shah A, Tamez H, Smith K, Thadhani R, Wolf M. Phosphorus binders and survival on hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:388–96.

Eddington H, Hoefield R, Sinha S, et al. Serum phosphate and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2251–7.

Martin KJ, Gonzalez EA. Prevention and control of phosphate retention/hyperphosphatemia in CKD-MBD: what is normal, when to start, and how to treat? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:440–6.

Molony DA, Stephens BW. Derangements in phosphate metabolism in chronic kidney diseases/end-stage renal disease: therapeutic considerations. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18:120–31.

Benini O, D’Alessandro C, Gianfaldoni D, Cupisti A. Extra-phosphate load from food additives in commonly eaten foods: a real and insidious danger for renal patients. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21:303–8.

Cupisti A, Benini O, Ferretti V, et al. Novel differential measurement of natural and added phosphorus in cooked ham with or without preservatives. J Ren Nutr. 2012;22:533–40.

Slatopolsky E, Weerts C, Norwood K, et al. Long-term effects of calcium carbonate and 2.5 mEq/liter calcium dialysate on mineral metabolism. Kidney Int. 1989;36:897–903.

Emmett M, Sirmon MD, Kirkpatrick WG, et al. Calcium acetate control of serum phosphorus in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991;17:544–50.

Rudnicki M, Hyldstrup L, Petersen LJ, et al. Effect of oral calcium on noninvasive indices of bone formation and bone mass in hemodialysis patients: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1994;20:130–4.

Navaneethan SD, Palmer SC, Craig JC, et al. Benefits and harms of phosphate binders in CKD: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:619–37.

Chertow GM, Burke SK, Raggi P, Treat to Goal Working Group. Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62:245–52.

Block GA, Spiegel DM, Ehrlich J, et al. Effects of sevelamer and calcium on coronary artery calcification in patients new to hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1815–24.

Qunibi W, Moustafa M, Muenz LR, CARE-2 Investigators, et al. A 1-year randomized trial of calcium acetate versus sevelamer on progression of coronary artery calcification in hemodialysis patients with comparable lipid control: the Calcium Acetate Renagel Evaluation-2 (CARE-2) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:952–65.

Barreto DV, Barreto FC, De Carvalho AB, et al. Phosphate binder impact on bone remodeling and coronary calcification: results from the BRiC study. Nephron Clin Pract. 2008;110:273–83.

Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:53–8.

Bushinsky DA. Contribution of intestine, bone, kidney, and dialysis to extracellular fluid calcium content. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(Suppl 1):S12–22.

Gotch FA, Levin N, Kotanko P. Calcium balance in dialysis is best managed by adjusting dialysate calcium guided by kinetic modeling of the interrelationship between calcium intake, dose of vitamin D analogues and the dialysate calcium concentration. Blood Purif. 2010;29:163–76.

Bosticardo G, Malberti F, Basile C, et al. Optimizing the dialysate calcium concentration in bicarbonate haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2489–96.

Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, et al. Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1478–83.

Goodman WG, London G, Amann K, et al. Vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:572–9.

Giachelli CM. Vascular calcification mechanisms. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2959–64.

Yang H, Curinga G, Giachelli CM. Elevated extracellular calcium levels induce smooth muscle cell matrix mineralization in vitro. Kidney Int. 2004;66:246768.

Koiwa F, Onoda N, Kato H, et al. Prospective randomized multicenter trial of sevelamer hydrochloride and calcium carbonate for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in hemodialysis patients in Japan. Ther Apher Dial. 2005;9:340–6.

Ouellet G, Cardinal H, Mailhot M, et al. Does concomitant administration of sevelamer and calcium carbonate modify the control of phosphatemia? Ther Apher Dial. 2010;14:172–7.

Slatopolsky EA, Burke SK, Dillon MA. Renagel, a nonabsorbed calcium- and aluminum-free phosphate binder, lowers serum phosphorus and parathyroid hormone. The RenaGel Study Group. Kidney Int. 1999;55:299–307.

Fan S, Ross C, Mitra S, et al. A randomized, crossover design study of sevelamer carbonate powder and sevelamer hydrochloride tablets in chronic kidney disease patients on haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3794–9.

Chertow GM, Dillon M, Burke SK, et al. A randomized trial of sevelamer hydrochloride (RenaGel) with and without supplemental calcium. Strategies for the control of hyperphosphatemia and hyperparathyroidism in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 1999;51:18–26.

Braun J, Asmus HG, Holzer H, Brunkhorst R, Krause R, Schulz W, Neumayer HH, Raggi P, Bommer J. Long-term comparison of a calcium-free phosphate binder and calcium carbonate-phosphorus metabolism and cardiovascular calcification. Clin Nephrol. 2004;62:104–15.

Block GA, Raggi P, Bellasi A, et al. Mortality effect of coronary calcification and phosphate binder choice in incident hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2007;71:438–41.

De Francisco AL, Leidig M, Covic AC, et al. Evaluation of calcium acetate/magnesium carbonate as a phosphate binder compared with sevelamer hydrochloride in haemodialysis patients: a controlled randomized study (CALMAG study) assessing efficacy and tolerability. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:3707–17.

Fishbane S, Delmez J, Suki WN, et al. A randomized, parallel, open-label study to compare once-daily sevelamer carbonate powder dosing with thrice-daily sevelamer hydrochloride tablet dosing in CKD patients on hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:307–15.

Ketteler M, Rix M, Fan S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of sevelamer carbonate in hyperphosphatemic patients who have chronic kidney disease and are not on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1125–30.

Delmez J, Block G, Robertson J, et al. A randomized, double-blind, crossover design study of sevelamer hydrochloride and sevelamer carbonate in patients on hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol. 2007;68:386–91.

Hutchison AJ, Maes B, Vanwalleghem J, et al. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of lanthanum carbonate in hyperphosphatemia: a 6-month, randomized, comparative trial versus calcium carbonate. Nephron Clin Pract. 2005;100:c8–19.

Hutchison AJ, Laville M. Switching to lanthanum carbonate monotherapy provides effective phosphate control with a low tablet burden. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3677–84.

Mehrotra R, Martin KJ, Fishbane S, et al. Higher strength lanthanum carbonate provides serum phosphorus control with a low tablet burden and is preferred by patients and physicians: a multicenter study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1437–45.

Sprague SM, Abboud H, Qiu P, et al. Lanthanum carbonate reduces phosphorus burden in patients with CKD stages 3 and 4: a randomized trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:178–85.

Finn WF. Lanthanum carbonate versus standard therapy for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia: safety and efficacy in chronic maintenance hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2006;65:191–202.

Hutchison AJ, Maes B, Vanwalleghem J, et al. Long-term efficacy and tolerability of lanthanum carbonate: results from a 3-year study. Nephron Clin Pract. 2006;102:c61–71.

Lee YK, Choi HY, Shin SK, et al. Effect of lanthanum carbonate on phosphate control in continuos ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients in Korea: a randomized prospective study. Clin Nephrol. 2013;79:136–42.

Sprague SM, Ross EA, Nath SD, et al. Lanthanum carbonate vs. sevelamer hydrochloride for the reduction of serum phosphorus in hemodialysis patients: a crossover study. Clin Nephrol. 2009;72:252–8.

Kasai S, Sato K, Murata Y, et al. Randomized crossover study of the efficacy and safety of sevelamer hydrochloride and lanthanum carbonate in Japanese patients undergoing hemodialysis. Ther Apher Dial. 2012;16(4):341–9.

Slatopolsky E, Liapis H, Finch J. Progressive accumulation of lanthanum in the liver of normal and uremic rats. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2809–13.

Spasovski GB, Sikole A, Gelev S, et al. Evolution of bone and plasma concentration of lanthanum in dialysis patients before, during 1 year of treatment with lanthanum carbonate and after 2 years of follow-up. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2217–24.

Guillot AP, Hood VL, Runge CF, et al. The use of magnesium-containing phosphate binders in patients with end-stage renal disease on maintenance hemodialysis. Nephron. 1982;30:114–7.

Spiegel DM. Magnesium in chronic kidney disease: unanswered questions. Blood Purif. 2011;31:172–6.

Moriniere P, Vinatier I, Westeel PF, et al. Magnesium hydroxide as a complementary aluminium-free phosphate binder to moderate doses of oral calcium in uraemic patients on chronic haemodialysis: lack of deleterious effect on bone mineralisation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1988;3:651–6.

Delmez JA, Kelber J, Norword KY, et al. Magnesium carbonate as a phosphorus binder: a prospective, controlled, crossover study. Kidney Int. 1996;49:163–7.

Tzanakis IP, Papadaki AN, Wei M, et al. Magnesium carbonate for phosphate control in patients on hemodialysis. A randomized controlled trial. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40:193–201.

Spiegel DM, Farmer B, Smits G, et al. Magnesium carbonate is an effective phosphate binder for chronic hemodialysis patients: a pilot study. J Ren Nutr. 2007;17:416–22.

McIntyre CW, Pai P, Warwick G, et al. Iron–magnesium hydroxycarbonate (Fermagate): a novel noncalcium-containing phosphate binder for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:401–9.

Navarro-Gonzalez JF, Mora-Fernandez C, et al. Clinical implications of disordered magnesium homeostasis in chronic renal failure and dialysis. Semin Dial. 2009;22:37–44.

Alfrey AC, Miller NL. Bone magnesium pools in uremia. J Clin Investig. 1973;52:3019–27.

Gonella M, Ballanti P, Della Rocca C, et al. Improved bone morphology by normalizing serum magnesium in chronically hemodialyzed patients. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1988;14:240–5.

Kakuta T, Tanaka R, Hyodo T. Effect of sevelamer and calcium-based phosphate binders on coronary artery calcification and accumulation of circulating advanced glycation end products in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:422–31.

Russo D, Miranda I, Ruocco C, et al. The progression of coronary artery calcification in predialysis patients on calcium carbonate or sevelamer. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1255–61.

Salusky IB, Goodman WG, Sahney S, et al. Sevelamer controls parathyroid hormone-induced bone disease as efficiently as calcium carbonate without increasing serum calcium levels during therapy with active vitamin D sterols. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2501–8.

Ferreira A, Frazao JM, Monier-Faugere MC, et al. Effects of sevelamer hydrochloride and calcium carbonate on renal osteodystrophy in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:405–12.

Shantouf R, Budoff MJ, Ahmadi N, et al. Effects of sevelamer and calcium-based phosphate binders on lipid and inflammatory markers in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:275–9.

Navarro-González JF, Mora-Fernández C, Muros de Fuentes M, et al. Effect of phosphate binders on serum inflammatory profile, soluble CD14, and endotoxin levels in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2272–9.

Caglar K, Yilmaz MI, Saglam M, et al. Short-term treatment with sevelamer increases serum fetuin-A concentration and improves endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease stage 4 patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:61–8.

Brandenburg VM, Schlieper G, Heussen N, et al. Serological cardiovascular and mortality risk predictors in dialysis patients receiving sevelamer: a prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2672–9.

Oliveira RB, Cancela AL, Graciolli FG, et al. Early control of PTH and FGF-23 in normophosphatemic CKD patients: a new target in CKD-MBD therapy? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:286–91.

Striker GE. Beyond phosphate binding: the effect of binder therapy on novel biomarkers may have clinical implications for the management of chronic kidney disease patients. Kidney Int. 2009;76(Suppl 114):S1–2.

Suki WN, Zabaneh R, Cangiano JL, et al. Effects of sevelamer and calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1130–7.

Jamal SA, Fitchett D, Lok CE, et al. The effects of calcium-based versus non-calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality among patients with chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3168–74.

Di Iorio B, Bellasi A, Russo D, et al. Mortality in kidney disease patients treated with phosphate binders: a randomized study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:487–93.

Wilson R, Zhang P, Smyth M, et al. Assessment of survival in a 2-year comparative study of lanthanum carbonate versus standard therapy. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:3021–8.

Toussaint ND, Lau KK, Polkinghorne KR, Kerr PG, et al. Attenuation of aortic calcification with lanthanum carbonate versus calciumbased phosphate binders in haemodialysis: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Nephrology (Carlton). 2011;16:290–8.

D’Haese PC, Spasovski GB, Sikole A, et al. A multicenter study on the effects of lanthanum carbonate (Fosrenol) and calcium carbonate on renal bone disease in dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2003;85:S73–8.

Malluche HH, Siami GA, Swanepoel C, et al. Improvements in renal osteodystrophy in patients treated with lanthanum carbonate for two years. Clin Nephrol. 2008;70:284–95.

Kopple JD. The National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for dietary protein intake for chronic dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:S66–70.

Shinaberger CS, Greenland S, Kopple JD, et al. Is controlling phosphorus by decreasing dietary protein intake beneficial or harmful in persons with chronic kidney disease? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1511–8.

KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: management of progression and complications of CKD. Kidney Int. 2013;3;S73–90.

Moore LW, Byham-Gray LD, Scott Parrot J, et al. The mean dietary protein intake at different stages of chronic kidney disease is higher than current guidelines. Kidney Int. 2013. doi:10.1038/ki.2012.420. [Epub ahead of print].

Trumbo P, Schlicker S, Yates AA, et al. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1621–30.

Cianciaruso B, Pota A, Pisani A, et al. Metabolic effects of two low protein diets in chronic kidney disease stage 4–5: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;23:636–44.

Mircescu G, Garneata L, Stancu SH, et al. Effects of a supplemented hypoproteic diet in chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr. 2007;17:179–88.

Murtaugh MA, Filipowicz R, Baird BC, et al. Dietary phosphorus intake and mortality in moderate chronic kidney disease: NHANES III. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:990–6.

Newsome B, Ix JH, Tighiouart H, et al. Effect of protein restriction on serum and urine phosphate in the modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.01.007.

Lopes AA, Tong L, Thumma J, et al. Phosphate binder use and mortality among hemodialysis patients in the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS): evaluation of possible confounding by nutritional status. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:90–101.

Soroka SD, Beard KM, Mendelssohn DC, et al. Mineral metabolism management in canadian peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2012;75:410–5.

Manns B, Klarenbach S, Lee H, et al. Economic evaluation of sevelamer in patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2867–78.

Bernard L, Mendelssohn D, Dunn E, et al. A modeled economic evaluation of sevelamer for treatment of hyperphosphatemia associated with chronic kidney disease among patients on dialysis in the United Kingdom. J Med Econ. 2013;16:1–9.

Karamanidou C, Clatworthy J, Weinman J, et al. A systematic review of the prevalence and determinants of nonadherence to phosphate binding medication in patients with end-stage renal disease. BMC Nephrol. 2008;9:2.

Arenas MD, Malek T, Gil MT, et al. Challenge of phosphorus control in hemodialysis patients: a problem of adherence? J Nephrol. 2010;23:525–34.

Chiu YW, Teitelbaum I, Misra M, et al. Pill burden, adherence, hyperphosphatemia, and quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1089–96.

Chertow GM, Raggi P, McCarthy JT, et al. The effect of sevelamer and calcium acetate on proxies of atherosclerotic and arteriosclerotic vascular disease in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2003;23:307–14.

Caldeira D, Amaral T, David C, et al. Educational strategies to reduce serum phosphorus in hyperphosphatemic patients with chronic kidney disease: systematic review with meta-analysis. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21:285–94.

Gardulf A, Pålsson M, Nicolay U. Education for dialysis patients lowers long-term phosphate levels and maintains health-related quality of life. Clin Nephrol. 2011;75:319–27.

Acknowledgments

No funding was provided for preparation of the manuscript. The author declares that he has received lecture fees from AMGEN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malberti, F. Hyperphosphataemia: Treatment Options. Drugs 73, 673–688 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-013-0054-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-013-0054-y