Abstract

As of 31 December, 2023, 31 observational studies have been published, including a total of 6081 patients who underwent a switch from one biosimilar to another biosimilar of the same reference biologic. Most studies evaluated infliximab, while a smaller number evaluated adalimumab, rituximab or etanercept. Indications studied now include sarcoidosis, as well as the indications previously reported of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis/ankylosing spondylitis and inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis). This updated data set includes eight additional studies and 2386 more patients compared with those included in an earlier systematic review of biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching. In addition, since the earlier systematic review was published in 2022, the European Medicines Agency has stated that reference-to-biosimilar and biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching in the European Union is safe and efficacy remains unchanged after switching. Furthermore, following a review of the available evidence, the US Food and Drug Administration has confirmed that initial safety and immunogenicity concerns related to biosimilar switching are unfounded and that no differences are observed in efficacy, safety or immunogenicity following one or more switches. The availability of this new efficacy and safety data together with the supportive statements from the European Medicines Agency and the Food and Drug Administration re-confirm the conclusion that as a scientific matter, biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching is an effective clinical practice, with no new safety concerns. Any suggestions to the contrary are not supported by the evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

The published data supporting the practice of biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching have grown to include (as of 31 December, 2023) 31 observational studies with a cumulative total of 6081 patients across all studies. |

The availability of the existing efficacy and safety data confirms that as a scientific matter, biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching is an effective clinical practice, with no new safety concerns. This conclusion is supported by statements from both the European Medicines Agency and the US Food and Drug Administration. |

This analysis adds to the evidence that theoretical concerns about clinical efficacy and/or safety being impacted through multiple switches, including biosimilar-to-biosimilar switches, are not justified. |

1 Introduction

Biosimilars are becoming an accepted alternative to reference biologics in many therapeutic areas, including immune-mediated diseases and oncology [1]. As of December 2023, there are more than 90 biosimilars approved in the European Union (EU) and more than 40 approved in the USA [2, 3]. Furthermore, for many molecules, several biosimilars are approved and commercially available, including infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, insulins, trastuzumab and bevacizumab, among others. As a result, patients, healthcare professionals and formularies are increasingly exposed to the practice of switching between different biosimilars of the same biological reference product in real-world settings.

The first systematic review of biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies was published by Cohen et al. in July 2022 [4]. The cut-off date for inclusion of studies in this review was 31 December, 2021. The literature search identified 23 observational studies (N = 3657 patients) that contained switching data on safety and/or effectiveness. Since that time, there have been further developments with regard to biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the European Heads of Medicines Agencies (HMA) have since issued a joint position statement supporting the safety and efficacy of switching to and between biosimilar medicines in the EU [5]. A questions and answers document was subsequently issued to further clarify and support their position [6].

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate safety outcomes when switching between biosimilars and reference biologics. This found no differences in safety or immunogenicity between patients who were switched and those who remained on a reference biologic or a biosimilar [7]. The FDA has also developed an educational presentation that addresses the theoretical safety and immunological concerns related to biosimilar switching [8].

Several new biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies have been published in 2022 and 2023. In addition, data from some studies that were available only in abstract form as of 31 December, 2021 have since been published as full articles in peer-reviewed journals. In light of this new evidence, it is timely to provide an update to the Cohen et al. (2022) systematic review.

2 Methods

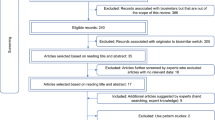

The same process described in Cohen et al. [4] was followed for the literature search, study selection, data extraction, quality assessment and analysis. Several approaches were used to identify biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies published from 1 January, 2022 through 31 December, 2023. For some studies, outcomes (e.g. patient perception and clinical endpoints) were published in multiple articles or congress abstracts. Therefore, we were careful to only count a particular study once, irrespective of the number of publications.

2.1 Literature Search

A systematic literature search was conducted for the period from 1 January, 2022 through 31 December, 2023, using the same electronic databases as previously [4]. For the search terms, the list of MeSH keywords was expanded to include all biological drugs for which multiple biosimilars were commercially available in the USA, EU, Canada and Australia during the search period (erythropoietin/epoetin, human growth hormone/somatropin, filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, rituximab, teriparatide, trastuzumab and bevacizumab).

2.2 Additional Searches

Hand searching of scientific publications cited in trade press and medical communication articles that reviewed the scientific literature was conducted to identify any studies published between 1 January, 2022 and 31 December, 2023 that were not retrieved by the systematic search. In addition, three other systematic reviews included biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies. These reviews were examined to identify any further studies for inclusion that may have not been previously detected in our search: (1) a review of 19 anti-tumor necrosis factor biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies by Allocati et al. in August 2022 [9]; (2) a review of 15 studies describing multiple switches between reference biologics and biosimilars by Lasala et al. in November 2022 [10]; and (3) a review of 43 anti-tumor necrosis factor switching studies by Meade et al. in 2023 [11].

3 Results

3.1 Overall Results

As of 31 December, 2023, 31 observational studies of biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching containing efficacy and/or safety data have been published (Table 1). These studies included a total of 6081 patients. Most studies evaluated infliximab, while a smaller number evaluated adalimumab, rituximab or etanercept. Indications studied included rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), axial spondyloarthritis/ankylosing spondylitis (AxSpA) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).

In addition to the 23 studies included in the earlier Cohen et al. review [4], eight additional studies were identified, of which six are reported in full publications and two reported in congress abstracts. Five congress abstracts that were included in Cohen et al. [4] have since been published as full articles in peer-reviewed journals. The systematic review conducted by Allocati et al. [9] contained one biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching study that was not included in Cohen et al. [4] and that was not detected in our systematic search for the current publication.

3.2 Studies Not Included in Cohen et al. (2022) [4]

3.2.1 Biosimilar‑to‑Biosimilar Switch Studies of Infliximab Biosimilars

Sarcoidosis is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease in which nodules called granulomas form throughout the body. After failure of systemic glucocorticoids and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, anti-tumor necrosis factor agents such as infliximab are typically considered. In a single-center retrospective cohort study, all patients diagnosed with severe refractory sarcoidosis receiving reference infliximab Remicade® or biosimilar infliximab Inflectra® were switched to biosimilar infliximab Flixabi® [12]. The primary outcome was infliximab discontinuation within 6 months of switching. Out of 86 patients who switched to Flixabi®, 79 patients had complete data and 55 had previously received Inflectra®. None of these patients discontinued infliximab during the first 6 months after switching. Five patients reported an adverse event (AE) related to Flixabi® treatment. No changes from baseline in forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume in 1 second, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, the 6-minute walking distance test and infliximab trough concentrations 26 weeks after switching were observed. The authors concluded that switching from Remicade® or Inflectra® to Flixabi® did not result in treatment discontinuation or loss of clinical, functional or inflammatory remission.

In a prospective observational cohort study, a total of 297 patients with IBD (CD, n = 196 [66%]; UC/IBD unclassified, n = 101 [34%]) were switched from infliximab biosimilar SB2 to infliximab biosimilar CT‐P13 [13]. During the follow-up period, 9.4% of patients discontinued infliximab treatment. Reasons for discontinuation included immunogenicity, secondary loss of response, AEs, patient’s choice and primary non-response. Infliximab persistence was analysed based on the number of switches, with higher persistence rates observed in patients with fewer switches. However, after adjusting for confounders, the number of switches was not independently associated with infliximab persistence. A multivariable analysis identified the absence of biochemical remission, a diagnosis of UC/IBD unclassified, detectable antibodies against infliximab at the switch and the time on infliximab as independent predictors for infliximab persistence, rather than the number of infliximab switches. Effectiveness of treatment, as measured by clinical, biochemical and fecal biomarker remission rates, was comparable at baseline, week 12 and week 24. De novo infliximab antibody development did not differ significantly based on the number of switches. Infliximab concentrations did not differ across timepoints, although dose adjustments were allowed. Six AEs were reported in five patients, with three classified as severe AEs leading to drug discontinuation. The authors concluded that multiple successive switches from reference infliximab to biosimilars appear effective and well tolerated, irrespective of the number of switches.

A prospective observational study conducted at a single IBD center between 2021 and 2022 assessed the effectiveness and safety of treatment after switching a cohort of 287 patients with idiopathic IBD from infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 to infliximab biosimilar SB2 [14]. After the 13-month post-switch period, treatment persistence was 86.4% (95% confidence interval 82.5, 90.4) and there were no significant changes in clinical or biological parameters of IBD activity. Reasons for discontinuation after the 13-month period were listed as patient-reported loss of efficacy, side effects of therapy or loss to follow-up. No higher manifestations of immunogenicity of the treatment were detected after switching from CT-P13 to SB2. The results of this study showed that switching from CT-P13 to SB2 is effective and well tolerated in the majority of patients with IBD on long-term maintenance therapy.

A psychometric and clinical observational study of 119 patients with IBD (CD, n = 73 [61%]; UC, n = 46 [39%]) evaluated the effects of switching from CT-P13 to SB2 [15]. Patient-reported outcomes and psychometric tests were used to assess the impact of the switch. The study also measured C-reactive protein levels, concomitant steroid use and AEs. Serum samples were collected to measure infliximab and anti-infliximab trough concentrations, as well as cytokine levels. No significant changes in psychometric assessments, clinical laboratory measurements, pharmacokinetics or AEs were observed during the follow-up. Overall, the results suggested that switching from CT-P13 to SB2 can be considered safe, does not significantly impact treatment effectiveness or drug pharmacokinetics, and is seemingly not associated with any major negative psychological implications.

3.2.2 Biosimilar‑to‑Biosimilar Switch Studies of Adalimumab Biosimilars

A study evaluated short-term and medium-term clinical efficacy, drug sustainability and safety of switches from reference adalimumab to biosimilar adalimumab and between adalimumab biosimilars in 276 patients with IBD (CD, n = 205; UC, n = 71) [16]. A total of 102 patients underwent a biosimilar-to-biosimilar switch (adalimumab biosimilar ABP501 to adalimumab GP2017, n = 85; adalimumab biosimilar MSB11022 to adalimumab GP2017, n = 17). No significant differences were found in clinical remission rates at weeks 8–12 prior to switching, at the time of switching or at weeks 8–12 and 20–24 post-switching in patients switching from biosimilar to biosimilar (72.0%, 77.4%, 84.9% and 77.6%, respectively). Mean C-reactive protein levels remained unchanged in both cohorts. Drug survival was 85.8% after 40 weeks. Two cases of skin reactions, one of which led to treatment discontinuation, were reported. Results showed that clinical remission rates remained unchanged after switching, and a medium-term clinical benefit was maintained. Drug sustainability was high and did not differ between patients who switched from the reference product to a biosimilar and from biosimilar to biosimilar.

A single-center study compared the effectiveness of switching from adalimumab biosimilar ABP501 to adalimumab biosimilar SB5 in 40 patients with chronic inflammatory arthritis (RA, n = 12 [30%]; PsA, n = 25 [62%]; AxSpA, n = 3 [8%]) [17]. After 4 months of SB5 treatment, no differences were seen in 28-joint Disease Activity Score C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) or Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) measures for RA and PsA, respectively, or in the percentage of patients in remission or with low disease activity compared with baseline. Likewise, no differences were found in any patient-reported outcome measures. Three patients discontinued SB5 because of a lack of efficacy, and three discontinued because of AEs. Out of the 40 patients switched, two switched back to ABP501 because of paresthesia and a lack of efficacy, respectively.

An observational retrospective study was conducted in two centers in northern Italy in 72 patients with IBD (CD, n = 65 [90%]; UC, n = 7 [10%]) treated with adalimumab biosimilar GP2017 as initial therapy or as a switch from the reference product or other biosimilars [18]. Of these patients, ten had been treated with unspecified adalimumab biosimilars and were then transitioned to GP2017. In total, 6/10 (60%) patients were in remission at the time of switching, and 7/10 patients were in remission after 6 and 12 months. Drug persistence was similar in patients starting GP2017 as their first therapy and in those who switched to GP2017 from either reference adalimumab or another biosimilar adalimumab. No serious AEs were detected in this study.

Another study evaluated 127 patients with inflammatory diseases (RA, n = 41 [32%]; PsA, n = 52 [41%]; AxSpA, n = 34 [27%]) who were initially switched from reference adalimumab to adalimumab biosimilar ABP501, and then 1 year later from ABP501 to adalimumab biosimilar SB5 [19]. Retention rates at 1 year after the biosimilar-to-biosimilar switch were the same as at 1 year after the reference biologic to the first biosimilar switch: the 1-year retention rate for ABP501 was 84.4%, 78% and 76% in patients with AxSpA, RA and PsA, respectively. The 1-year retention rate for SB5 was 82.1%, 78.7% and 77.5%, respectively. As confidence intervals were not reported for patient retention values, it is not possible to determine whether the observed differences across indications were statistically meaningful. Disease activity, as measured by DAS28, DAPSA and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index for AxSpA, remained stable over the 3 years of the study. The authors concluded that there was no difference in terms of efficacy when switching from reference adalimumab to ABP501 or from ABP501 to SB5.

3.2.3 Abstracts That Have Since Been Published as Full Articles

Of the ten congress abstracts identified by Cohen et al. [4], five have since been published as full articles in peer-reviewed journals. Of these, two reported patient numbers larger than those in the congress abstracts. As they included new data, we have reviewed these two articles below.

The largest study of biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching conducted to date was a prospective observational cohort study conducted using the DANBIO health registry system in Denmark [20]. In total, 1605 patients (RA, n = 685; PsA, n = 314; and AxSpA, n = 606) were switched from biosimilar infliximab CT-P13 to biosimilar infliximab GP1111. Patients were classified as reference product naive or reference product treated. Drug retention, drug activity levels (assessed using the Clinical Disease Activity Index or Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score) and safety were monitored for a 1-year post-switch. The authors reported that “changes in disease activity pre- and post-switch were close to zero.” Retention was higher in reference biologic-experienced patients and those with low disease activity, suggesting that outcomes are affected by patient-related rather than drug-related factors. Stratified by indication, the retention rate was 80–87% for reference product-naïve patients (highest in patients with AxSpA) and 90–96% for reference product-experienced patients (lowest in patients with RA). The relatively high retention rates in patients with AxSpA compared with the other indications are consistent with results reported by Parisi et al. [19] and is an observation that warrants further analysis.

The prospective observational PERFUSE study was a long-term, non-interventional, multicenter study of patients with IBD receiving infliximab biosimilar SB2 in France, either as their first infliximab treatment (n = 85) or after transition from treatment with reference infliximab (n = 442) or another infliximab biosimilar (n = 289) [21]. After 1 year of treatment on SB2, measures were made of drug retention, disease activity (Harvey–Bradshaw Index for UC and the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index for CD), immunogenicity and safety (serious and non-serious treatment-emergent AEs). Among patients who had been treated with a prior infliximab biosimilar and then switched to SB2, the proportions of patients in remission at baseline, month 6 and month 12 remained unchanged in the UC cohort, and were comparable or higher in the CD cohort. No immunogenicity or safety signals were detected after the biosimilar-to-biosimilar switch.

4 Discussion

The additional effectiveness and safety data from biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies presented here confirm the conclusion reached by the previous systematic review of Cohen et al. [4], demonstrating that biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching is an effective clinical practice that is not associated with safety concerns. The extent to which biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching is already occurring in the real-world setting is not entirely clear. While this systematic review identified studies published in the scientific literature, this practice may already be occurring more broadly, especially in healthcare systems that are impacted heavily by economic drivers for product selection, such as the use of tenders or exclusive contracts. Alternatively, it may only be occurring in limited circumstances in some healthcare systems because of a reluctance of some healthcare professionals to adopt a new biosimilar use paradigm.

There are multiple permutations of switching related to biosimilars, including switching to, from and between biosimilars [22]. It is important that individual patients, patient advocacy groups, healthcare professionals and policy specialists, including those from health authorities, are knowledgeable about the fact that the reference biologic and all biosimilars of the reference biologic are the very same molecule, with an identical amino acid structure and no clinically meaningful differences. Given the sameness of the molecules, from a scientific perspective, one expects that biosimilars and reference biologics will have the same clinical and safety profiles even after switches. Individuals who are not familiar with this fact, or the existing and expansive data already supporting biosimilars, may be cautious in their use of and expectations for biosimilars. Increased knowledge about the underlying science as well as the safety and efficacy of biosimilars will likely lead to increased patient access to these molecules, with the possibilities of significant savings for patients and healthcare systems.

The EMA and the HMA issued a joint statement on 21 April, 2023 entitled “Statement on the scientific rationale supporting interchangeability of biosimilar medicines in the EU” that explicitly supports biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching of biosimilars approved in the EU [5]. This states that the “HMA and EMA consider that once a biosimilar is approved in the EU it is interchangeable, which means the biosimilar can be used instead of its reference product (or vice versa) or one biosimilar can be replaced with another biosimilar of the same reference product.” The EMA and HMA cited several publications from leading European regulators and scientists as helping to establish the foundation for their joint statement [23,24,25].

The FDA is limited in its ability to address the practice of biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching because US legislation states that a biosimilar is only approved relative to its reference biologic. However, in response to concerns regarding safety and potential immunogenicity when switching from reference biologics to biosimilars and from one biosimilar to another, the FDA has examined evidence from reviews of randomised and real-world studies and found no negative impact of switching on safety or immunogenicity. They concluded that “theoretical safety and immunological concerns with switching have not been demonstrated in patients” [8].

The efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of switching once from a reference biologic to a biosimilar have been evaluated in many observational studies and randomised clinical trials, with the results summarised in two large and comprehensive systematic reviews [26, 27]. These revealed no loss of efficacy or any new safety concerns when switching from reference biologics to EMA-approved or FDA-approved biosimilars.

Given the variability in study designs and analyses, neither of the two systematic reviews was able to conduct a meta-analysis of the data. To address this limitation, the FDA undertook a systematic review that identified all randomised clinical trials and extension studies with switching treatment periods that were incorporated into data provided to the FDA for review and that are available in summary documents available on the FDA website [7]. These data were supplemented by additional information from peer-reviewed publications of a reference biologic to biosimilar switching not included in the FDA reviews. They identified 44 switching time periods from 31 unique studies of 21 different biosimilars that included 5252 patients. Meta-analyses were undertaken to estimate the relative risk of death, serious AEs and drug discontinuation across all studies. Drug discontinuation is an imperfect measure of effectiveness but can also reflect patient dissatisfaction for a variety of reasons. Immunogenicity data (total anti-drug antibody levels and neutralising antibody levels) were also compared across the studies but could not be integrated into a meta-analysis because of differences between the studies in assay design and performance. The results were unambiguous, with an overall risk difference (95% confidence interval) of − 0.00 (− 0.00, 0.00), 0.00 (− 0.01, 0.01) and 0.00 (− 0.01, 0.00) across switching treatment periods for deaths, serious AEs and discontinuations, respectively. Immunogenicity data were equally unambiguous, with a similar incidence of anti-drug antibodies and neutralising antibodies seen in patients who switched to or from a biosimilar to its reference biologic, compared to patients who were not switched.

Our analysis of biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies is limited by the fact that so far, only observations studies have been reported. However, some of the observational data in biosimilar infliximab-to-biosimilar infliximab switching were obtained from DANBIO, the Danish national biologics registry [20]. Large-scale registries have the potential to provide broad, real-world, population-level data that can be used to address research questions in an observational manner. For example, the DANBIO registry could be used to evaluate other biosimilar molecules. In addition, other large registries may also provide useful real-world information on biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching.

Another limitation is that only a small number of biosimilars have been evaluated to date in biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies, even though many more molecules already have multiple biosimilars available for them. We believe that the preponderance of infliximab studies, and to a lesser degree adalimumab studies, in this data set reflects the fact that multiple biosimilars to infliximab and adalimumab became available and were adopted widely relatively early, and does not reflect a reluctance to use other biosimilar molecules.

With the exception of a single rituximab study [28], all studies identified in this systematic review were conducted in chronic disease indications. As with the rituximab study identified, biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching may also occur with oncolytic drugs, but the shorter treatment cycles of those therapies makes that possibility less likely.

Furthermore, the number of patients enrolled in many of the individual studies was relatively small, which may limit the ability to draw conclusions from them as a stand-alone dataset. However, the findings from smaller studies can be considered as supportive when consistent with those of larger studies. Several of the studies included in this review have to date only been published as abstracts. It is generally understood that the amount of data provided within an abstract is typically less than that included in a peer-reviewed publication.

Despite these limitations, we propose that there is sufficient robust data to draw scientific conclusions about biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching. Additional data on biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching will undoubtedly be forthcoming in the future, but based on the current evidence, there is no longer any valid reason to consider this practice to be potentially unsafe.

These conclusions regarding the safety and effectiveness of the practice of biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching do not negate the need for patient counseling prior to being switched from one biosimilar to another. Patients have the right to be involved in and make choices regarding their care, so should be provided with appropriate information to enable them to do so. It is also important that patient care is founded on a strong relationship between the patient and their healthcare team.

5 Current Opinion

Currently, 31 observational studies (N = 6081 patients) have provided safety and/or effectiveness data on biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching. The EMA and FDA have recently released statements supportive of switching to biosimilars, including switching from one biosimilar to another biosimilar of the same reference biologic. We believe that the available data suggest that as a scientific matter, the practice of biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching is as safe and effective as being treated solely with either a reference biologic or a single biosimilar, or the switch from a reference biologic to its biosimilar. Any suggestions to the contrary are not supported by clinical evidence or the underlying science.

References

US Food and Drug Administration. Biosimilars. 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/therapeutic-biologics-applications-bla/biosimilars. Accessed 12 Dec 2023.

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biosimilars approved in Europe. 2023. https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/general/biosimilars-approved-in-europe. Accessed 12 Dec 2023.

US Food and Drug Administration. Biosimilar product information. 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-product-information. Accessed 12 Dec 2023.

Cohen HP, Hachaichi S, Bodenmueller W, Kvien TK, Danese S, Blauvelt A. Switching from one biosimilar to another biosimilar of the same reference biologic: a systematic review of studies. BioDrugs. 2022;36:625–37.

European Medicines Agency and Heads of Medicines Agencies. EMA/627319/2022 Statement on the scientific rationale supporting interchangeability of biosimilar medicines in the EU. 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/public-statement/statement-scientific-rationale-supporting-interchangeability-biosimilar-medicines-eu_en.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov 2023.

European Medicines Agency. Q&A on the statement on the scientific rationale supporting interchangeability of biosimilar medicines in the EU. 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/qa-statement-scientific-rationale-supporting-interchangeability-biosimilar-medicines-eu_en.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov 2023.

Herndon TM, Ausin C, Brahme NN, et al. Safety outcomes when switching between biosimilars and reference biologics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2023;18:e0292231.

Brahme N, Skibinski S, Ikenberry S. FDA Drug Topics: Biosimilars: a review of scientific, regulatory, and clinical considerations for health care providers. 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/169599/download. Accessed 29 Nov 2023.

Allocati E, Godman B, Gobbi M, Garattini S, Banzi R. Switching among biosimilars: a review of clinical evidence. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:917814.

Lasala R, Abrate P, Zovi A, Santoleri F. Safety and effectiveness of multiple switching between originators and biosimilars: literature review and status report on interchangeability. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2023;57:352–64.

Meade S, Squirell E, Hoang TT, Chow J, Rosenfeld G. An update on anti-TNF biosimilar switching: real-world clinical effectiveness and safety. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2023;7:30–45.

Peters BJM, Bhatoe A, Vorselaars ADM, Veltkamp M. Switching to an infliximab biosimilar was safe and effective in Dutch sarcoidosis patients. Cells. 2021;10:441.

Gros B, Plevris N, Constantine-Cooke N, et al. Multiple infliximab biosimilar switches appear to be safe and effective in a real-world inflammatory bowel disease cohort. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2023;11:179–88.

Reissigová J, Černá K, Lukáš M Jr, et al. Switch from biosimilar infliximab CT-P13 to biosimilar infliximab SB-2 in the long-term maintenance therapy in IBD patients: prospective observational study. Gastroent Hepatol. 2023;77:336–41.

Privitera G, Melita E, Monastero L, et al. PP0855 Infliximab biosimilar switch is safe and effective, it does not have major psychological implications and does not affet pharmacokinetics in a large cohort of patients with IBD. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2023;11(Suppl. 8):1029.

Lontai L, Gonczi L, Balogh F, et al. Non-medical switch from the originator to biosimilar and between biosimilars of adalimumab in inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective, multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54:1639–45.

Scrivo R, Castellani C, Mancuso S, et al. Effectiveness of non-medical switch from adalimumab bio-originator to SB5 biosimilar and from ABP501 adalimumab biosimilar to SB5 biosimilar in patients with chronic inflammatory arthropathies: a monocentric observational study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2023;41:613–9.

Vernero M, Bezzio C, Ribaldone DG, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab biosimilar GP2017 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6839.

Parisi S, Becciolini A, Ditto MC, et al. AB0341 Efficacy and drug survival after multiple-switching from adalimumab originator to the biosimilars ABP501 and SB5: a real-life study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(Suppl. 1):1295–6.

Nabi H, Hendricks O, Jensen DV, et al. Infliximab biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease: clinical outcomes in real-world patients from the DANBIO registry. RMD Open. 2022;8:e002560.

Bouhnik Y, Fautrel B, Beaugerie L, et al. PERFUSE: a French non-interventional study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving infliximab biosimilar SB2: a 12-month analysis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848221145654.

Mysler E, Azevedo VF, Danese S, et al. Biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching: what is the rationale and current experience? Drugs. 2021;81:1859–79.

Kurki P, van Aerts L, Wolff-Holz E, et al. Interchangeability of biosimilars: a European perspective. BioDrugs. 2017;31:83–91.

Barbier L, Mbuaki A, Simoens S, et al. Regulatory information and guidance on biosimilars and their use across Europe: a call for strengthened one voice messaging. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:820755.

Kurki P, Barry S, Bourges I, et al. Safety, immunogenicity and interchangeability of biosimilar monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins: a regulatory perspective. Drugs. 2021;81:1881–96.

Barbier L, Ebbers HC, Declerck P, Simoens S, Vulto AG, Huys I. The efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of switching between reference biopharmaceuticals and biosimilars: a systematic review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108:734–55.

Cohen HP, Blauvelt A, Rifkin RM, Danese S, Gokhale SB, Woollett G. Switching reference medicines to biosimilars: a systematic literature review of clinical outcomes. Drugs. 2018;78:463–78.

Urru SAM, Spila Alegiani S, Guella A, Traversa G, Campomori A. Safety of switching between rituximab biosimilars in onco-hematology. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5956.

Trystram N, Abitbol V, Tannoury J, et al. Outcomes after double switching from originator Infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 and biosimilar SB2 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53:887–99.

Khan N, Patel D, Pernes T, et al. The efficacy and safety of switching from originator infliximab to single or double switch biosimilar among a nationwide cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Crohns Colitis. 2021;3:otab022.

Luber RP, O’Neill R, Singh S, et al. An observational study of switching infliximab biosimilar: no adverse impact on inflammatory bowel disease control or drug levels with first or second switch. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54:678–88.

Mazza S, Piazza OSN, Conforti FS, et al. Safety and clinical efficacy of the double switch from originator infliximab to biosimilars CT-P13 and SB2 in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (SCESICS): a multicenter cohort study. Clin Transl Sci. 2022;15:172–81.

Hanzel J, Jansen JM, Ter Steege RWF, Gecse KB, D’Haens GR. Multiple switches from the originator infliximab to biosimilars is effective and safe in inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:495–501.

Lovero R, Losurdo G, La Fortezza RF, et al. Safety and efficacy of switching from infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 to infliximab biosimilar SB2 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;32:201–7.

Macaluso FS, Fries W, Viola A, et al. The SPOSIB SB2 Sicilian Cohort: safety and effectiveness of infliximab biosimilar SB2 in inflammatory bowel diseases, including multiple switches. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:182–9.

Gisondi P, Virga C, Piaserico S, et al. Switching from one infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) to another infliximab biosimilar (SB2) in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:397–8.

Lauret A, Molto A, Abitbol V, et al. Effects of successive switches to different biosimilars infliximab on immunogenicity in chronic inflammatory diseases in daily clinical practice. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50:1449–56.

Harris C, Harris RJ, Young D, et al. Clinical outcomes and patient experience of biosimilar to biosimilar infliximab switching in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective, single-centre, phase IV interventional study with a nested qualitative study. GastroHep. 2023;2023:1248526.

Fautrel B, Bouhnik Y, Dieude P, et al. Real-world evidence of the use of the infliximab biosimilar SB2: data from the PERFUSE study. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2023;7:rkad031.

Ribaldone DG, Tribocco E, Rosso C, et al. Switching from biosimilar to biosimilar adalimumab, including multiple switching, in Crohn’s disease: a prospective study. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3387.

Derikx L, Dolby HW, Plevris N, et al. Effectiveness and safety of adalimumab biosimilar SB5 in inflammatory bowel disease: outcomes in originator to SB5 switch, double biosimilar switch and bio-naive SB5 observational cohorts. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:2011–21.

Piaserico S, Conti A, Messina F, et al. Cross-switch from etanercept originator to biosimilar SB4 and to GP2015 in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. BioDrugs. 2021;35:469–71.

Kiltz U, Tsiami S, Baraliakos X, Andreica I, Kiefer D, Braun J. Effectiveness and safety of a biosimilar-to-biosimilar switch of the TNF inhibitor etanercept in patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2022;14:17597.

Siakavellas SI, Barrett RA, Plevris N, et al. 610 Both single and multiple switching between infliximab biosimilars can be safe and effective in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): real world outcomes from the Edinburgh IBD unit. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1–120.

O’Neill R, Singh S, Luber R. 4CPS-108 a review of infliximab biosimilar to biosimilar switch: Remsima to Flixabi. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2020;27(Suppl. 1):A98.

Mott A, Mott A, Taherzadeh N, et al. PMO-29 Switching between infliximab biosimilars: experience from two inflammatory bowel disease centres. Gut. 2021;70:A92.

Cunningham F, Shurmunov A, Dong D, Salone C, Zacher J, Glassman P. 977 Biosimilar safety dashboard to assess switching in veterans. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28:474–5.

Gall S, Kiltz U, Kobylinski T, et al. POS0301 No major differences between patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease who underwent mono- or multiswitching of biosimilars in routine care (PERCEPTION study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:376.

Acknowledgements

Eve Blumson of Apollo, OPEN Health Communications provided editorial support that consisted of a data check, proofreading and formatting of the publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Financial assistance for editorial support and Open Access charges was provided by Sandoz Deutschland/Hexal AG.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

Hillel P. Cohen is an employee of Sandoz Inc. Wolfram Bodenmueller is an employee of Sandoz Deutschland/Hexal AG. Sandoz manufactures and markets multiple biosimilars worldwide, including several discussed in this publication.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

All publications included in this systematic review are available in the public domain.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

HPC developed the concept for this publication, conducted the literature reviews and drafted the initial manuscript. WB reviewed and revised the clinical data summaries. Both authors participated in the writing of the publication and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, H.P., Bodenmueller, W. Additional Data in Expanded Patient Populations and New Indications Support the Practice of Biosimilar-to-Biosimilar Switching. BioDrugs (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-024-00655-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-024-00655-4