Abstract

The AB3-type LaCaMgNi9 compound was synthesized using mechanical alloying (MA) starting from elemental La, Ca, Mg, and Ni in the atomic ratio 1:1:1:9. X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were used to study the phase evolution and formation/kinetic mechanism as a function of milling time (4–30 h). The results show multiphase alloys containing LaCaMgNi9 as a main phase with trigonal PuNi3-type structure (R-3m space group) where Ca atoms occupy preferentially the 3a site, while La and Mg atoms occupy the 6c site with a mean composition CaLa1.2(2)Mg0.8(2)Ni9. The hydrogenation properties of the alloys were examined by solid–gas reaction at room temperature. The PCI curves showed a plateau pressure of 0.25 bar which corresponds to the AB3 phase. The hydrogen absorption capacity of the AB3 phase is equal to 5.6 H/u.fAB3.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hydrogen storage alloys have been widely investigated as negative electrode materials for Ni–MH (Nickel–Metal Hydride) secondary batteries for their high energy density, long cycle life, low memory effect, and the absence of cadmium or other toxic heavy metals [1–6].

Recently, a new family of PuNi3-type structure has attracted attention as an electrode material for Ni/MH battery because of their high hydrogen storage capacity and moderate hydrogen equilibrium pressure [7]. Many high capacity alloys with the AB 3 composition (A: rare earth metal, Ca and Mg; B: transition metals) have been reported. These alloys have long periodic one-dimensional superstructure in which AB 5 unit (CaCu5-type structure) and A 2 B 4 unit (Laves-type structure) are rhombohedrally stacked with a ratio of 1:1 along the c-axis direction [8].

Kadir et al. [1] have discovered that RMg2Ni9 (R: rare earth) alloys with rhombohedral PuNi3-type structure presenting a 1:1 stacking of the AB 5 and A 2 B 4 units are interesting compounds for hydrogen storage. A representative description of the stacking arrangement of RMg2Ni9-type alloy is given in ref [9]. The interest of such system is to take advantage from the properties of AB 5 and A 2 B 4 units to obtain compounds with enhanced behavior toward hydrogen absorption [9, 10]. Partial Ca and Mg substitution for A yields hydrogen storage capacity of about 1.9 wt% and discharge capacity of about 370 mAh/g [11–13].

The results reported by Kadir et al. have motivated intense interest in A–Mg–Ni-based hydrogen storage alloys. Chen et al. [14] have obtained several kinds of A–Mg–Ni-based alloys with a PuNi3-type structure including LaCaMgNi9. Crystal structure analysis of this later compound has indicated that the Mg atoms occupy only 6c sites, while La and Ca atoms are located at the 3a and 6c sites. The structural data of LaCaMgNi9 with PuNi3-type structure are reported in Table 1.

LaCaMgNi9 compound has been traditionally produced by melting or sintering processes. Nevertheless, using melting technique, it is difficult to obtain stoichiometric LaCaMgNi9 because the high vapor pressures of Ca and Mg lead to losses of both elements by evaporation. A further difficulty is the high oxidation rate of Ca and Mg at elevated temperature [15]. However, it is possible to avoid these difficulties using mechanical alloying (MA). This technique was considered since 70 years (Benjamin [16] Yermakov et al. [17]) as a useful process in solid state reaction for the synthesis of very high melting point compounds (ceramics, carbides), alloys containing immiscible elements or elements having very different vapor pressures, high pressure or high temperature unstable alloys, amorphous alloys, etc. It has been also observed that large surface area and reduced particle size of the material are crucial parameters to improve the hydrogenation properties of metal hydride systems. Indeed, they can induce a reduction of the activation time, an improvement of the kinetic and an increase of the absorption capacity [18]. As MA induces an increase of the specific surface area and the density of the defect on the surface as well as in the bulk, it appears to be a suitable process for the synthesis of nanocrystalline LaCaMgNi9 alloy with good hydrogen absorption properties.

The aim of this work was therefore the synthesis of nanocrystalline LaCaMgNi9 compound by MA in order to study, on the one hand, the contribution of this process on the structural properties of this intermetallic compound usually obtained by co-fusion and on the other hand, the effect of the nanocrystalline state on its hydrogen absorption properties. Its crystalline structure was determined and refined from X-ray powder diffraction data. The morphology was studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), while the microstructure and the chemical composition were analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The thermodynamic properties were investigated using differential scanning calorimetry for the alloy and solid–gas measurements (PCI) for hydrogenation.

Experimental details

MA was performed with a Fritsch Pulverisette P7 planetary ball mill. A 2 g stoichiometric mixture of elemental powders of Ni (Acros 99.9 %, 50 µm), Ca (Prolabo 99.3 %, 40 µm), Mg (Acros 99.9 %, 50 µm), and La (VWR 99.9 %, 40 µm) was placed in a carbide container of 45 ml capacity. All the sample handlings were carried out inside an Ar-filled glove box in order to avoid possible oxidation of reactant elements. The carbide container was loaded with five steel balls (12 mm diameter) with a ball to powder mass ratio equal to 17:1. The disk rotation speed was set to 400 rpm. These MA conditions correspond to 0.06 J/Hit kinetic shock energy, 83 Hz shock frequency, and 2.76 W/g shock power [19, 20]. The obtained samples were named St with S as sample and t as MA time in hour (t varies from 0 to 30 h).

Structural characterization was performed at room temperature by X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) using (θ–2θ) Panalytical X’Pert Pro MPD diffractometer with a copper anti-cathode (λCuKα1 = 1.54060 Å, λCuKα2 = 1.54443 Å, ratio = 0.5). The patterns were recorded over the range 10°–110° in 2θ by step of 0.04°. Phase analysis and structural determination were performed using Fullprof software [21] based on the Rietveld method [22, 23]. The background contribution was refined in the final fit. The refined parameters were, respectively, the following: zero shift, cell parameters, occupancies, z position of La and Mg in the 6c sites, Lorentzian constant Y and Gaussian constant U, and finally the background. At the last cycle, all the parameters were refined simultaneously.

The morphology of the S30 mechanically alloyed sample was studied by scanning electron microscopy using a SEM-FEG LEO 1530 device. The microstructural state of the powder was studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a Tecnai F20 microscope. Images were recorded using a bright-field mode. Elemental mapping analysis was carried out by energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis. To obtain thin samples for the TEM characterization, powders from the alloy and aluminum were mixed together, and then cold-rolled and thinned with an argon ion beam in a GATAN precision ion polishing system.

Hydrogenation properties at 25 °C were determined by measuring the Pressure-Composition-Temperature isotherm (PCI) using the Sievert’s method for pressure between 0.1 and 10 MPa. Sample was outgassed under primary vacuum for 24 h at 120 °C before starting the measurement. Thermal analysis was carried out by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using a DSC Q100 of TA Instrument.

Results and discussion

X-ray diffraction results

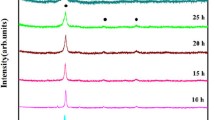

The structural evolution of the mechanically alloyed samples has been studied by X-ray powder diffraction. Figure 1a shows the XRD pattern of the S0 sample where all the diffraction lines of the starting elements are present. The diffraction peaks of nickel are the most intense, while those of the other elements are barely detectable. This fact is mainly related to the low contents of Ca, Mg, and La (5.47, 3.32 and 18.9 wt%, respectively) as compared to the Ni one (72.21 wt%).

The XRD patterns of the samples alloyed mechanically for different times are compared in Fig. 2. It can be seen that all the diffraction peaks have a significant line broadening. This latter is certainly due to the reduction of the crystallite size and the increase of the internal strains induced from the fracture and welding processes [24] in agreement with the mechanism proposed by Fecht [25]. The continuous particle refinement leads to the observed nanocrystalline state. It is also well established (Koch [26], Suzuki [27], Abdellaoui and Gaffet [19, 20]) that, when starting from pure elements, the phase formation by MA is induced by a long distance diffusion of the different elements in an intragranular common region and a local chemical and structural ordering according to the initial chemical composition. The driving force for this reaction is the difference between the free energy of the mixture of elements and that of the formed compound. So, as the ball milling progress, the free energy of the crystalline mixture (∆G BM mixture) increases due to the increase of the defect concentration induced by plastic deformation (∆GBM mixture = ∆Ginitial mixture + ∆Gdefect). When the free energy induced by defects (∆Gdefect) exceeds the activation energy (E a) of the transformation from the mixture to an appropriate crystalline compound, this latter reaction will occur [28]. The ∆Gdefect is function of the injected shock power (P inj), whereas the amount of the formed crystalline compound depends on the cumulated energy (E cum = P inj * ∆t with ∆t the milling duration) [19].

Figure 2 shows that the diffraction peaks of elemental La, Ca, and Mg metals disappear after 8 h of milling. Ni diffraction peaks remain till 20 h and disappear for further durations. After 4 h of milling new peaks appear, characteristic of a ANi2 phase, crystallizing in a MgCu2-type cubic structure [29]. As the refined cell parameter (a = 7.176 Å) is smaller than that of LaNi2.17 [7.34(3) Å] and CaNi2 [a = 7.25(1) Å], there is probably a random mixture of La, Ca, and Mg atoms on the A site. This phase disappears after 8 h of alloying time. After 10 h of MA, the desired AB 3 phase with PuNi3-type structure and LaNi5 phase start to be formed. For larger milling time, peak intensities of both AB 3 and LaNi5 phases increase while those of the initial reactant Ni decrease.

The Rietveld method was used to refine the structural parameters (cell parameters, atomic position, and occupancies) and to calculate the weight content of the existing phases in order to study the evolution of phase composition and phase abundance of the milled mixture. For milling time larger than 20 h, as the diffraction peaks of both AB3 and LaNi5 phases are broad and sometimes overlapped, the cell parameters of the LaNi5 phase were kept fixed in order to limit the number of refined variables. The LaNi5 cell parameter values [a = 4.9844(9) Å and c = 4.0211(9) Å] were obtained from the refinement of single LaNi5 phase synthesized by MA in the same MA conditions than the quaternary alloy. As Mg does not substitute to La in LaNi5, and Ca for La substitution leads to different peak intensities, this assumption is reasonable. The Rietveld refinement of the XRD pattern of single phase LaNi5 compound obtained after 15 h of MA is shown in Fig. 3a.

Assuming that Mg atoms can only occupy the 6c site in the PuNi3-type structure [30], two different combinations of Ca and La atoms have been tested by Rietveld refinement to find the repartition of these elements among the two available sites 3a and 6c. In the first case, all Mg atoms were kept on the 6c site and the La and Ca atoms were randomly distributed on the two 3a and 6c sites. The FullProf calculations lead to negative occupancy factors for La in the 3a site and Ca in the 6c one, meaning that La is better suited in the 6c position and Ca in the 3a one. In the second case, the 3a site was set fully occupied by Ca atoms, while La and Mg atoms were distributed in 6c site with the assumption that nLa + nMg = 6. This configuration was more suitable with better reliability factors for the refinement. This procedure was then applied for XRD patterns analysis of all samples.

The strong preference of calcium atoms for the 3a site in the AB3-type phase is characteristic of a ternary ordered compound with the CaMg2Ni9-type structure as reported by Kadir et al. [11]. However, these results are different from those reported by Kadir et al. [1] for (La0.65Ca0.35)(Mg1.32Ca0.68)Ni9 compound where Ca was randomly distributed over the 3a and 6c sites. Table 2 summarizes occupancy factors and z atomic position of La and Mg in 6c site of the AB 3 phase structure for all alloying durations. These results show that the 6c sites are composed of La and Mg with small fluctuations of the La/Mg ratio (within the errors bars). The mean composition calculated using these values is CaLa1.2(2)Mg0.8(2)Ni9. The loss of Mg with respect to the nominal composition can be explained by its welding on the vial surface.

Figure 3b–d shows the refined XRD patterns of S4, S10, and S30 samples and the corresponding Rietveld structural parameters are reported in Tables 2 and 3. The evolution of all phase abundances versus MA duration is reported in Fig. 4. It indicates that the weight contents of Ca(La, Mg)2Ni9 and LaNi5 phases increase with milling time, whereas that of Ni decreases until it disappears after 25 h of MA. In this work, it is worth to note that MA process can be described in three steps. For short time (i.e., between 4 and 12 h), we observe a rapid and important increase of the amount of the formed phases and a rapid decrease of the amount of initial Ni. For milling time ranging between 12 and 20 h, we obtain a stationary state formed by an AB 3 and LaNi5 phases with a small amount of remaining Ni. Above 20 h of milling, the remaining Ni has disappeared and the AB 3 amount increases at the expense of that of LaNi5.

The lattice parameter variations of the Ca(La, Mg)2Ni9 phase as function of MA duration are displayed in Fig. 5. It is observed that the lattice parameters do not vary with milling time but fluctuate around an average value. However, it is worthy to note that the mean c lattice parameter is larger than that reported for the CaMg2Ni9 phase (c = 23.7868 Å [11]). This can be explained by the higher value of the La metallic radius (1.87 Å), compared to the Mg one (1.6 Å) as the La atoms are located along the c-axis.

Thermal treatment

DSC measurement has been performed on the S30 sample. There are two DSC curves measured upon heating. The first DSC curve presents two broad exothermic peaks: the first at 200 °C and the second at higher temperature of about 420 °C (Fig. 6). The second curves measured in a second cycle shows that all these peaks have disappeared indicating non reversible phase transitions. The first peak of curve 1 corresponds to the restoration of defects created by the MA process, while the second one corresponds to the crystallization of the formed phases [31–33]. The XRD pattern was measured and analyzed after DSC. XRD pattern shows thinner diffraction lines related to both the release of defects and the increase of particle size. Both LaNi5 phase and AB 3-type phase are identified. XRD patterns after MA and DSC are compared in Fig. 7 and the results of refinement are presented in Table 3. The cell parameters of the LaNi5 phase remain close to that of a single LaNi5 sample milled by MA to serve as a reference. The a cell parameter and the cell volume of the AB3 phase decrease after DSC. This might be due to the difference in the 3a and 6c site occupation by both La and Ca atoms. In fact, as previously presented, after MA, the refinement was made on the basis of a total 3a site occupation by Ca atoms, while after DSC Ca and La atoms were randomly distributed between the two latter sites. A decrease of the amount of AB3-type for the benefit of LaNi5 phase after DSC is also noticed and it could be attributed to the loss of Mg and Ca elements constituent of the AB3. This result is different from the one reported by Hua et al. [34] for the La2MgNi9 alloy on which annealing increases the abundance of the AB3-type phase.

Morphological and microstructural study

SEM micrography showing the morphology of the S30 sample is reported in Fig. 8a. The powder is composed of large agglomerates of more than 5 µm. These agglomerates are made of several small (0.1–1 µm) deformed particles welded together. We assume that after a given MA time, equilibrium is reached between the rate of welding (which tends to increase the average particle size) and the rate of fracturing (which tends to decrease the average particle size) [27]. Moreover, the EDS spectra collected in different designed spots (Fig. 6b–d) qualitatively show that the obtained quaternary alloy has a homogenous composition.

HRTEM analysis was carried out in order to study the microstructure of the S30 sample. Figure 9 presents a HRTEM bright-field micrograph of this alloy. This figure shows nanoparticles with sizes ranging from 5 to 15 nm in agreement with grain size values calculated by X-ray diffraction. The A and B regions in Fig. 9 correspond, respectively, to Ca(La,Mg)2Ni9 and LaNi5 phases identified by their respective (009) and (110) atomic plans.

In this work, EDX coupled to HRTEM was used to perform semi-quantitative analysis. This technique is sufficient to determine the atomic ratio between elements in order to set the chemical formula of the analyzed sample.

The results of chemical analysis by TEM-EDX are in agreement with the HRTEM observation and confirm the presence of both Ca(La,Mg)2Ni9 and LaNi5 phases. The chemical composition of the AB 3-type phase was determined in several regions of the sample. Figure 10 shows the variation of the calculated atomic concentration of La, Ca, Mg, and Ni as well as the B/A ratio (where A = (La + Ca + Mg) and B = Ni) in different regions of the S30 sample. The results indicate that the selected particles are richer in La than Ca. All compositions can be assigned to a quaternary phase having a B/A ratio close to 3 in agreement with the nominal formula determined by Rietveld refinement.

Hydrogenation properties

The Pressure-Composition-Temperature Isotherm (PCI) of the S30 sample measured at room temperature is plotted in Fig. 11. Qualitatively, a careful look at the isotherm reveals that there is a significant absorption at very low pressure (first part of the PCT). As mentioned earlier, MA causes defects and particle size reduction. The enhanced absorption at low pressure is mostly due to the hydrogen adsorption in the defects in the surface [35]. The PCI curve exhibits a large plateau pressure at about 0.25 bar upon absorption.

Based on the values of the enthalpy (−35.3 kJ mol−1 H2) and the entropy (−120 J K−1 mol−1 H2) of the La0.5Ca1.5MgNi9 hydride formation reported by Chen et al. [2], the estimated plateau pressure value of this compound at 25 °C, will be 0.25 bar. So, we assume that the first plateau pressure corresponds to the hydride formation of the Ca(La,Mg)2Ni9 phase. The small bump, observed in the absorption curve, could be related to the LaNi5 contribution which plateau pressure is 1.89 bar at 25 °C according to Ngameni et al. [36].

Conclusion

A nanostructured AB 3 phase with PuNi3-type structure alloy has been synthesized at room temperature by mechanical alloying of a stoichiometric mixture of elemental La, Ca, Mg, and Ni.

Rietveld refinement shows that after 12 h of milling the AB 3-type phase becomes the main phase with a mean formula of CaLa1.2(2)Mg0.8(2)Ni9. In this phase, the Ca atoms occupy preferentially the 3a site, while La and Mg atoms are located in the 6c site. The weight content of this phase reaches 67 % after 30 h of MA. HRTEM analysis confirms that the S30 sample consists of two phases Ca(La,Mg)2Ni9 and LaNi5 at nanometer scale in agreement with the XRD data. Such nanostructuration of the active material is expected to be highly suitable for hydrogen absorption. Hydrogenation at room temperature shows that the compound can absorb about 6 H/f.u. The absorption PCI curve shows two distinct plateaus at pressures corresponding to Ca(La,Mg)2Ni9 and LaNi5 phases.

Further characterization of electrochemical and thermodynamic properties of the synthesized alloys will be achieved in the near future. Other synthesis routes will be investigated in order to increase the amount of the AB 3-type phase, which may be very promising as negative electrode material for Ni–MH batteries.

References

Kadir, k., Sakai, T., Uehare, I.: Structural investigation and hydrogen storage capacity of LaMg2Ni9 and La0.65Ca0.35Mg1.32Ca0.68Ni9 of the AB2C9 type structure. J. Alloys Compd. 302, 112 (2000)

Chen, J., Kuriyama, N., Takeshita, H.T., Tanaka, H., Sakai, T.: Hydrogen storage alloys with PuNi3-type structure as metal hydride electrodes. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 3, 249 (2000)

Liu, X.Y., Xu, L.Q., Jiang, W.Q., Li, G.X., Wei, W.L., Guo, J.: Effect of substituting Al for Co on the hydrogen storage performance of La0.7Mg0.3Ni2.6AlxCo0.5-x (x= 0-0.3) alloys. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 34, 2986 (2009)

Li, Y., Han, S., Li, J.H.: Study on kinetics and electrochemical of Ml0.7Mg0.3(Ni3.95Co0.75Mn0.15Al0.15)x (x= 0.60, 0.64, 0.68, 0.70, 0.76). Mater. Chem. Phys. 108, 92 (2008)

Dong, Z., Wu, Y., Ma, L., Shen, X.: Electrochemical properties of (La1-xTix)0.67Mg0.33Ni2.75Co0.25 (x=0-0.2 % at) hydrogen storage alloys. Mater. Res. Bull. 45, 256 (2010)

Dong, Z., Wu, Y., Ma, L.: Electrochemical hydrogen strorage properties of non-stoichimometric La0.7Mg0.3-xCaxNi2.8Co0.5 (x=0-0.1) electrode alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 509, 5280 (2011)

Liu, Y., Cao, Y., Huang, L., Gao, M.: Rare earth-Mg-Ni based hydrogen storage alloys as negative electrode materials for Ni-MH batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 509, 675 (2011)

Kadir, K., Sakai, T., Uehare, I.: Synthesis and structure determination of new series of hydrogen storage alloys RMg2Ni9 (R=La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm and Gd) built from MgNi2 laves type layers alternating with AB5 layers. J. Alloys Compd. 257, 115 (1997)

Latroche, M., Percheron-Guégan, A.: Structural and thermodynamic studies of some hydride forming RM3-type compounds (R= lanthanides, M= transition metal). J. Alloys Compd. 356–357, 461 (2003)

Ozaki, T., Kanemoto, M., Kakey, T.: Stacking structures and electrode performances of rare earth-Mg-Ni based alloys for advanced nickel-metal hydride battery. J. Alloys Compd. 446–447, 620 (2007)

Kadir, K., Kuriyama, N., Sakai, T., Uehare, I.: Structural investigation and hydrogen capacity of CaMg2Ni9: new phase in the AB2C9 system isostructural with LaMg2Ni9. J. Alloys Compd. 284, 145 (1999)

Kadir, K., Sakai, T., Uehare, I.: Structural investigation and hydrogen capacity of YMg2Ni9 and (Y0.5Ca0.5)(MgCa)Ni9: new phases isostructral with LaMg2Ni9. J. Alloys Compd. 287, 264 (1999)

Chu, H.L., Qiu, S.J.: Effect of ball milling time on the electrochemical properties of La-Mg-Ni based hydrogen storage composite alloys. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 32, 4925 (2007)

Chen, J., Kuriyama, N., Takeshita, H.T., Tanaka, H., Sakai, T.: Hydriding properties of LaNi3 and CaNi3 and their substitues with PuNi3-type structure. J. Alloys Compd. 302, 304 (2001)

Miraglia, S., Girard, G., Fruchart, D., Liang, G., Huot, J., Schulz, R.: Structural characterization and some hydrogen absorption properties of (MgxCa1-x)Ni2.6: a new phase in the Mg-Ca-Ni system. J. Alloys Compd. 478, L33 (2009)

Benjamin, J.S.: Dispersion strengthened superalloys by mechanical alloying. Metall. Trans 1, 2943 (1970)

Yermakov, A.E., Yurchikov, E.E., Barinov, V.A.: The magnetic properties of amorphous Y-Co alloy powders obtained by mechancal comminution. Phys. Met. Metall. 52, 50 (1981)

Abdellauoi, M., Gracco, D., Percheron-Guégan, A.: Structural characterization and reversible hydrogen absorption properties of Mg2Ni rich nanocomposite material synthesized by mechanical alloying. J. Alloys Compd. 268, 233 (1998)

Abdellaoui, M., Gaffet, E.: The physics of mechanical alloying in a modified horizontal rod mill: mathematical treatment. Acta Metall. Mater. 43(3), 351 (1995)

Abdellaoui, M., Gaffet, E.: A mathematical and experimental dynamical phase diagram for ball milled Ni10Zr7. J. Alloys Compd. 209, 351 (1994)

Rodriguez-Carvajal, J.: Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction. Phys. B 192, 55 (1993)

Rietveld, H.M.: Line profiles of neutron powder-diffraction peaks for structure refinement. Acta Cristallgr. 22, 151 (1967)

Rietveld, H.M.: A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 2, 65 (1969)

Zuo, B., Saraswati, N., Sritharan, T., Hng, H.H.: Production and annealing of nanocrystalline Fe-Si and Fe-Si-Al alloy powders. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 371, 210 (2004)

Fecht, H.J.: Nanostructure formation by mechanical attrition. Nanostruct. Mater. 6, 33 (1995)

Koch, C.C.: Amorphization by mechanical alloying. J. Non Cryst. Solids 117–118, 670 (1990)

Suzuki, K.: A structural study of the solid state vitrification of metals and oxides by ball milling. J. Non Cryst. Solids 112, 23 (1989)

Schwarz, R.B., Koch, C.C.: Formation of amorphous alloys by the mechanical alloying of crystalline powders of pure metals and powders of intermetallics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 49, 146 (1986)

Paul-Boncour, V., Percheron-Guégan, A., Diaf, M., Achard, J.C.: Structural characterization of RNi2 (R=La, Ce) intermetallic compound and their hydride. J. Less-Common Met. 131, 201 (1987)

Zhang, P., Wei, X., Liu, Y., Zhu, J.: The microstructures and electrochemical properties of non stoichiometric low-Co AB5 alloys containing small amounts of Mg. J. Alloys Compd. 399, 270 (2005)

Tao, J.M, Zhu, X.K., Scattergood, R.O., Koch, C.C.: The thermal stability of nanocrystalline Cu prepared by high energy ball milling. Mater. Des. 50, 22 (2013)

Abdellaoui, M., Gaffet, E.: Supersaturated A2 solid solution induced by ball milling in the Fe-Si system: structural and magnetic characterization and thermal stability. IEEE Trans. Magn. 30(6), 4887 (1994)

Abdellaoui, M.: Microstructural and thermal investigations of iron-silicon nanocomposite materials synthesized by rod milling. J. Alloys Compd. 264, 285 (1998)

Hu, W.K., Denys, R.V., Yartys, V.: Annealing effect on phase composition and electrochemical properties on the Co-free La2MgNi9 anode for Ni-metal hydride batteries. Electrochim. Acta 96, 27 (2013)

Joseph, B., Schiavo, B.: Effect of ball milling on the hydrogen sorption properties of LaNi5. J. Alloys Compd. 480, 912 (2009)

Ngameni, R., Mbemba, N., Grigorev, S.A.: Comparative analysis of the hydriding kinetics of LaNi5, La0.8Nd0.2Ni5 and La0.7Ce0.3Ni5 compounds. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 36, 4178 (2011)

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Dr E. Leroy for technical assistance in the TEM analysis. Financial support was guaranteed by the CMCU project (CMCU PHC Utique N 10G1208).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chebab, S., Abdellaoui, M., Latroche, M. et al. Structural and hydrogen storage properties of LaCaMgNi9-type alloy obtained by mechanical alloying. Mater Renew Sustain Energy 4, 13 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40243-015-0053-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40243-015-0053-x