Abstract

The purpose of this research is to synthesize the fragmented extant knowledge on flexible and green supply chain management (FGSCM) in the context of emerging economies and to unearth research gaps to motivate future research. We adopted a novel structured systematic literature review by triangulating a systematic literature review, text mining, and network analysis. Institutional theory and contingency theory were employed to analyze the results of the review. The results show that, firstly, research on FGSCM in emerging economies, despite its importance, is immature compared to general FGSCM literature. Second, the specificities of strategies and practices that distinguish this topic in emerging economies are discussed and the drivers and barriers are identified with respect to sources of institutional pressure. Third, a research framework for FGSCM in emerging economies is developed and 12 gaps for future research are identified. This study has exclusively developed a research framework for FGSCM in an emerging economy which has received the least consideration in the literature and practice. The framework was developed to synthesize the existing literature and to identify the research gaps to inspire future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Economic growth and consumerism have placed greater demands for energy and material consumption, resulting in increased concerns for environmental and natural resource preservation (Jia et al., 2018). Environmental issues are prime concerns for global economies due to global warming, increased pollution and depleting non-renewable resources (Malviya & Kant, 2015). Supply chain advancements since the 1990s introduced a new perspective that integrates environmental management within business operations to achieve a competitive advantage (Srivastava, 2007). Moreover, dissemination of flexibility from the manufacturing sector to the interorganizational and supply chain level created exciting, yet under-researched, opportunities for supply chain flexibility (Singh et al., 2020a, 2020b; Stevenson & Spring, 2007; Wadhwa & Rao, 2004).

Globalization resulted in increased demand for various products in the mid-twentieth century forcing global organizations to enter into new contexts of production where they had never operated before (Rajeev et al., 2017). The geographic extension of the supply chain resulted in more than 20% of the greenhouse gas to be emitted by organizations venturing on global platforms, due to the increased complexity of the sourcing and distribution channels as well as the socio-economic conditions of different countries (Dubey et al., 2017). Globalization not only created concerns vis-à-vis the ecological impact of supply chains, but also affected recent supply chain disruptions due to the Covid-19 pandemic. From this, it was established that the supply chain must be built flexibly to survive in volatile environments (Butt, 2021; Stevenson & Spring, 2007).

Growing environmental concerns and stringent environmental laws in developed countries have driven global companies to outsource the most polluting segments of their businesses to developing nations (Dwivedi et al., 2021; Garcia-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano & van der Meer, 2022; Geng et al., 2017a, 2017b). Among developing countries, emerging economies (e.g., Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, known as BRICS) are prime targets of multinational corporations due to a large consumer base, relatively disposable income, rapid industrialization, diversity of supply base, availability of skilled workforce, and lower operating costs (Tumpa et al., 2019). Emerging economies welcome foreign direct investment and benefit directly from globalization. This shift of location, however, has increased environmental concerns in emerging nations as well as the need for stricter environmental and social standards (Geng et al., 2017a, 2017b). On the other side, focal supply chain firms understood that the shift to emerging economies, despite the lower operating costs and new markets, involves unforeseen risks, which are specific to these countries. These risks can be mitigated only if the supply chain is proactive and if flexibility is built in supply chains in advance (Settembre-Blundo et al., 2021; Tukamuhabwa et al., 2017).

Recently, supply chain flexibility is becoming an attractive area of research for researchers and academicians (Singh et al., 2020a, 2020b). There is some research in this area, such as by Singh et al., (2020a, 2020b), who focus on measuring the performance of supply chain flexibility of an Indian soap manufacturing firm. Another research by Singh et al., (2020a, 2020b) focuses on mapping the causal relations among various supply chain flexibility dimensions and their impact on the Indian hygiene industry. However, there is limited research in the context of flexible green supply chain management (FGSCM). Research on FGSCM in emerging economies has been limited due to the contextual specificities of these countries such as the uncertainty inherent in their business environment and poor infrastructure to deal with sustainability issues (Silvestre, 2015; Singh et al., 2020a, 2020b). For example, 90% waste in India is dumped in the environment due to the lack of waste treatment and disposal facilities (Soda et al., 2015). Western corporates widely source from these manufacturers and service providers due to the availability of cheap labor and material. However, they have limited understanding of the context and poor visibility over the operational practices of their supply chains in such emerging economies (Rosin et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2019, 2020a, 2020b). Consequently, they are subject to scandals such as the Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh and enduring criticisms of overlooking environmental issues in their supply chain operations carried out in emerging economies (Bin Makhashen et al., 2020). Moreover, supply chain environmental issues exacerbated by disruptions in the recent pandemic have shown that sustainability and flexibility should be considered jointly in supply chain management, a need that has not been addressed in the literature hitherto (Paul & Chowdhury, 2020; Sassanelli & Terzi, 2022; Shibin et al., 2016).

Our initial review of the literature on FGSCM identifies the following gaps:

-

(a)

Limited research has been conducted on FGSCM in the context of emerging economies, despite the increasing trend of operations and procurement from these countries (Singh et al., 2019, 2020a, 2020b)

-

(b)

Despite the interconnectedness of flexibility and environmental sustainability in the supply chain management context, the literature has investigated these topics separately.

-

(c)

Existing frameworks for flexible or green supply chain management fall short of utility for emerging economies due to inherently different characteristics of the business environment in these countries.

-

(d)

While some systematic literature reviews in emerging economies have been conducted on flexible or green supply chain management barriers (Rahman et al., 2019; Shibin et al., 2016; Tumpa et al., 2019) and organizational performance (Geng et al., 2017a, 2017b), the literature scants systematic reviews that unearth the specificities and the sources of institutional pressures in emerging economies.

This review seeks to bridge these gaps by conducting a systematic literature review on FGSCM in emerging economies and addressing the following interrelated research questions -

-

i.

What is the status quo of FGSCM research in emerging economies?

-

ii.

What are the specificities of FGSCM strategies and practices in emerging economies?

-

iii.

What are the sources of institutional pressure, i.e., drivers and barriers, to adopt FGSCM strategies and practices in emerging economies?

-

iv.

How can the extant body of knowledge inform future research on FGSCM in emerging economies?

This article responds to the calls for further work on the FGSCM in emerging economies by proposing an innovative methodology that triangulates data from eclectic methods through a systematic literature review, text mining, and network analysis supported by two organizational theories for the cross-validation of findings and to eliminate subjectivity from the selection and review process. Three contributions to the literature of supply chain management are made. First, this article brings together the interrelated, yet separate, research developments in flexibility and environmental sustainability in supply chain management in emerging economies within the past 20 years. Second, it juxtaposes the FGSCM strategies and practices in emerging economies with the ones from the general literature, and thus unearths the contextual specificities of emerging economies using a contingency theory lens. Third, it identifies the sources of pressures that motivate or hinder FGSCM in emerging economies using institution theory to help policy makers advocate for FGSCM drivers and tackle the barriers.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the research design, theoretical perspectives, and the methodology used for the systematic literature review. Section 3 presents the results of a systematic literature review and provides infographics of the important trends found in the literature. Section 4 provides a thematic analysis of the results by identifying the strategies, practices, barriers, and enablers of FGSCM in emerging economies and comparing them against general FGSCM literature using the theoretical perspectives. Section 5 unearths the research gaps for future research and develops a research framework for FGSCM in emerging economies. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes the paper and provides the limitations.

Research Design and Methodology

This section describes the research design, including the methodology, theoretical underpinning, and analysis approaches. The research gap, as discussed in Sect. 1, is where flexible SCM, green SCM, and SCM in emerging economies overlap. Motivated by this research gap, our proposed methodology triangulates different approaches to extract, analyze, and synthesize extant literature on FGSCM in emerging economies. It combines a systematic literature review, text mining, and network analysis to identify, evaluate, and synthesize the existing research (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009). An eclectic theoretical underpinning of contingency theory and institutional theory is adopted throughout the review. The methodology integrates the findings to build a theoretical framework for FGSCM in emerging economies. Figure 1 shows the research gap, theoretical lens, and the steps of the proposed methodology.

Theoretical Perspective

A combined contingency theory and institutional theory lens was used to interpret the selected articles and develop a research framework. Contingency theory (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967) is a major theoretical lens that expresses different organizational systems are the results of differences in their operating context. Since one of the objectives of this research is to understand the specificities of FGSCM in emerging economies, it can serve as an appropriate theoretical lens to scrutinize the differences between FGSCM strategies and practices in developed and emerging economies. Furthermore, we considered drivers and barriers as sources of positive and negative pressures, respectively, on the firms to adopt FGSCM strategies and practices. We take an institutional theory perspective (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) to identify the source of drivers and barriers in emerging economies and discern whether they emerged to comply with regulations (coercive), to copy competitors or cope with cultural cognitive pressures (mimetic), or if they are in response to customer pressure (normative).

Stages of the Methodology

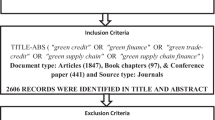

The methodology started with a search in electronic databases to locate, select, and evaluate extant studies. First, relevant keywords were identified based on the internal discussion of authors, all of whom are academics with a background in supply chain and operations management. A corporate practitioner from India, experienced in FGSCM, was involved in the discussions at a later stage to ensure the viability of the keywords. The initial keywords were refined into series of search strings using Boolean logic, for example, "Green AND/OR Supply Chain," and "Emerging AND/OR Economy AND/OR Flexible AND/OR Supply Chain." Nearly synonymous keywords such as "Developing Country" or "Sustainable/Ethical Supply Chain" were also used. The search strings were continuously refined, resulting in 26 of the most relevant strings that were used to search data on Web of Science, Science Direct, ABI/INFORM and Emerald Insight. The following exclusion criteria, as proposed by Newbert (2007), were used to narrow the results down to those which were more relevant.

-

Articles should be published in peer-reviewed scientific journals in English.

-

Only journals in the area of logistics, operations management, and supply chain management are included.

-

Articles should be published in the last 20 years.

-

Articles must contain at least one of the keywords in their title or abstract.

After reviewing the title, keywords, and abstract of the returned results, irrelevant articles were excluded and the rest of the articles were reviewed in their entirety, resulting in 108 articles shortlisted for the review. Table 1 shows the process of applying inclusion and exclusion criteria in detail and Fig. 2 summarizes Table 1. Figure 2 summarizes the total exclusion and remaining articles in each stage.

Next, to extract the key themes covered in the shortlisted articles, the text-mining technique was employed. The finalized articles from the previous stage were imported into NVivo12 for cross-validation. The articles were coded and categorized in terms of FGSCM conceptualization, operational impacts, strategies and practices, and drivers and barriers. All the authors were involved in coding and compiling the articles, which was later validated by an external researcher to ensure reproducibility of results and eliminating subjectivity. Text mining strengthened the validity and reliability of the selection process, including the finalized articles and the main themes. It also highlighted low values of relative frequencies as potential themes for future research.

Finally, to unearth the interconnection among the identified results, a network analysis was used. All major and minor categories and frequencies resulting from the previous stage were coded in a separate dataset and stored in NVivo12 for network analysis. Conducting a network analysis on this dataset identified the knowledge gaps of FGSCM in emerging economies and revealed the studies with higher interconnection. A combined contingency and institutional theory lens were used to synthesize the findings and develop a research framework.

Results of Systematic Literature Review

This section explains the stages of implementing the proposed research methodology and addressing the first research question on the status quo of FGSCM literature in emerging economies.

Phase I: Initial Search in Academic Databases

The concept of FGSCM gained its academic coverage in the 1990s (Fahimnia et al., 2015). However, most of the articles on FGSCM-related wider issues emerged after 2000 (Quarshie et al., 2016) followed by a sharp growth in academic publications afterward (Rafi-ul-Shan et al., 2018). Thus, the period used to conduct this review was determined to be from January 2000 to December 2021. Figures 3 compares the annual frequency of publications on general FGSCM and FGSCM in emerging economies indicating that, firstly, noticeably less research has been conducted on FGSCM in emerging economies and, secondly, the slope of increase is significantly lower for the latter.

Phase II: Text Mining

Conducting text mining using NVivo12 on the articles resulting from phase 1 facilitated visualization of the focus using word clouds as well as further analysis based on the industry sector, research methodology, and data analytics tools of the reviewed articles (Bin Makhashen et al., 2020). Figure 4 depicts the word cloud, highlighting the most frequently used words in the selected articles in bigger fonts, while other less frequent words appear in smaller fonts. A word cloud is a powerful visualization tool to identify common words in complex environments and facilitates unearthing dominant themes and keywords in a given context (Birko et al., 2015). The most frequently used words were “green” (word count: 5652), “supply chain” (4361), “sustainable” (4002), “environmental” (3794), “flexible” (3220), “management” (2431), and “emerging” (2187), followed by other keywords.

The analysis of articles by industry sector suggests that the extant empirical research on FGSCM used various industrial sectors, as shown in Fig. 5. The top three industries were the manufacturing industry 11.2% (29 articles), electronics and electrical industries 10.42% (27 articles), and textile and apparel industry 8.88% (23 articles). A figure of 12% of reviewed articles (31 articles) did not disclose the industry. The reviewed articles were sorted based on the country on which the study focused. The results, shown in Table 2, reveal that India (43 articles) and China (38 articles) were by far the two highest-researched emerging economies.

The articles were also analyzed based on research methodologies. As shown in Fig. 6, quantitative and mathematical modeling prevailed, which is at odds with the general trend of FGSCM literature. Our findings are at odds with Ansari and Kant (2017) who found more case studies and empirical qualitative studies, but are supported by Rajeev et al. (2017) who found that GSCM lacks qualitative research in the context of emerging economies when compared to the developed economies. It implies the maturity of literature on FGSCM as compared to FGSCM in emerging economies. Since quantitative methods were prevailing, the articles were further analyzed based on the applied data analytical tools, as shown in Fig. 7. Among various analytical tools applied, interpretive structural modeling (ISM) with 13 articles was the most popular data analysis technique, followed by Fuzzy TOPSIS (12 articles) and sensitivity analysis with 11 articles.

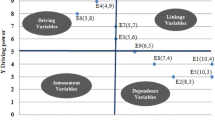

Phase III: Network Analysis

The articles with at least one citation were selected from the final list of articles, and their objectives and key findings were scrutinized to conduct network analysis. A network analysis was conducted on these articles. The results are depicted in Fig. 8.

It was found that FGSCM-related research is on the rise when compared to the FGSCM-related research in the context of emerging economies. Our network analysis demonstrated undirected empirical research on FGSCM in emerging economies, on the far edges of the network and distanced from the most cited FGSCM-related articles, enabling us to identify the most important contributions in the research domain. Based on the network analysis, key articles on FGSCM in emerging economies are highlighted. A summary of key contributions in the research domain is provided in the appendix.

Thematic Analysis of the Literature

This section provides an in-depth analysis of the selected articles from the systematic literature review. Firstly, FGSCM strategies and practices were extracted. Building upon the contingency theory, they were juxtaposed with the general literature of FGSCM to identify the contextual specificities of emerging economies (second research question). Secondly, the drivers and barriers of FGSCM in emerging economies were identified and categorized based on the source of institutional pressure using the institutional theory (third research question).

FGSCM Strategies and Practices

Many researchers attempted to identify and categorize FGSCM strategies and practices (e.g., Fang & Zhang, 2018; Nema et al., 2013; Srivastava, 2007; Zhu et al., 2007), but little research has been done on FGSCM strategies and practices in emerging economies and their specificities. Most of the terminologies, classifications, and categories of FGSCM strategies and practices were developed from the developed economies or network perspective. There are few studies that have researched the emerging economic context, such as those by Singh et al., (2020a, 2020b), Singh et al. (2019), and Singh and Acharya (2013) that extensively focused on developing a framework for supply chain flexibility. However, it was noticed that FGSCM strategies and practices received the least consideration in literature and practice. Thus, we identified FGSCM strategies and practices from the selected articles and juxtaposed them with the ones from the general FGSCM literature using the contingency theory lens. The results, summarized in Table 3, reveal that there are significant disparities between FGSCM strategies and practices in emerging economies and developed countries. These specificities should be considered when devising a FGSCM strategy or implementing practice in an emerging economy.

FGSCM Drivers and Barriers

Organizations in emerging economies face various drivers and barriers to adopt FGSCM strategies and practices. These pressures originate from different internal (from within the organization) and external (from outside the organization) stakeholders. This review unearthed major drivers and barriers and analyzed the sources from which they originated. Drivers related to government and regulations were categorized as coercive pressure. Drivers motivated by competitors or the cultural environment were considered as mimetic pressures. When a driver pertained to customer or market, it was perceived as normative pressure. Similarly, where a barrier was related to lack of government regulations or support, it was categorized as coercive pressure, indicating that governments should increase their support or exert further pressure to address the barrier. The same holds for barriers assigned to mimetic and normative pressures. When a driver or barrier originated from the internal environment of a firm, e.g., management commitment to environmental training, it is considered as an internal driver or barrier. For the sake of simplicity, when the analysis found management support as a driver and lack of management support as a barrier, for instance, it was only mentioned once in the list of drivers. Tables 4 and 5 provide a summary of identified drivers and barriers, respectively. These tables spotlight the two major key drivers/barriers (internal and external) of FGSCM in emerging economies.

Toward a Research Framework for FGSCM in Emerging Economies

This section addresses the fourth research question about synthesizing the extant body of knowledge to inform future research on FGSCM in emerging economies. Firstly, it puts forward research gaps based on the findings of the systematic literature review. Next, it integrates the findings of the study and the research gaps to develop a research framework for FGSCM in emerging economies.

Research Gaps to Inspire Future Research

Overall, the results confirm the findings of previous research (Geng et al., 2017a, 2017b; Silvestre, 2015) about the dearth of research on FGSCM in emerging economies. Despite the calls and dire need from a practice perspective, the research shows only a modest increase in this area. This section identifies the research gaps to develop a research framework and motivate future research.

Purchasing and Supply Management

The analysis of the word cloud reveals that some important themes in FGSCM such as purchasing and supply management are overlooked in emerging economies. Further analysis of institutional pressures shows that these areas are particularly important because larger multinational organizations often exert their purchasing power to increase their profit share, rather than to drive suppliers in emerging economies toward sustainability and flexibility. Moreover, no studies, apart from Adhikari and Bisi (2020), were found to investigate the effect of different types of contracts on sustainability.

Gap 1: To further investigate green/flexible purchasing and supply management in emerging economies and particularly how supplier–buyer power imbalance influences mainstreaming sustainability and flexibility in supply chains.

Gap 2: To study the impact of contract terms and contract types, e.g., profit-sharing contracts or performance-based contracts on the sustainability and flexibility of firms in emerging economies.

Industry and Country Analysis

The analysis of industries and countries show while some industries such as manufacturing, electronics, and the apparel industry received the most attention, other industries such as the service sector, SMEs, nonprofits, and development organizations are overlooked. This is an important observation as smaller firms in emerging economies are less equipped to develop FGSCM capabilities. Moreover, nonprofit and development organizations do not often account for sustainability in their strategy and operations (Zarei et al., 2019).

In terms of flexibility, our analysis of the literature shows that while the research has transcended beyond manufacturing flexibility in developed economies, as highlighted by Stevenson and Spring, (2007) and Yu et al. (2015), the interorganizational components of supply chain flexibility are still absent in emerging economies. In terms of countries, China and India received the greatest research attention while other emerging economies have been investigated less.

Gap 3: To investigate FGSCM in the service sector, SMEs, nonprofit and development supply chains in emerging economies

Gap 4: To transcend research beyond firm level flexibility and account for interorganizational and supply chain flexibility in emerging economies

Gap 5: To study FGSCM in less explored emerging economies such as Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Turkey and to conduct comparative cross-country analysis with the extant studies in China and India.

Methodology and Theory

In terms of methodology, unlike the trend in general FGSCM literature where qualitative studies prevail (Ansari & Kant, 2017), the reviewed articles heavily used quantitative methods such as mathematical modeling (31%) and surveys (20%). Moreover, collaboration and action research aims at generating contextual knowledge (Coughlan & Coghlan, 2002), making it a perfect methodology to elaborate on the context of emerging economies. However, no participatory or action research methodologies were found during the review. In turn, the dearth of qualitative methods led to poor theory application and development. The review of Geng et al., (2017a, 2017b) identified that the majority of articles in emerging economies had not specified any theory in the period 1996–2015. Our review supports their findings and postulates that in the period 2000–2020, insufficient theory development, testing, and elaboration still prevails.

Gap 6: To conduct case studies and participatory/action research and further theory application and development on FGSCM in emerging economies

Context Specificity

Using the contingency theory lens helped to juxtapose the studies in general FGSCM with the ones in emerging economies (Table 3) and revealed that the contextual specificities in emerging economies reduce the slope of FGSCM evolution trajectory (supported by Silvestre, 2015). From the theoretical perspective, such specificities are the contingency factors in the context of an emerging economy that drive organizations to adopt different decisions vis-a-vis their operating context. Therefore, an interesting avenue for future research is studying how organizations, especially focal business firms, operating in emerging economies align their strategies and practices (response variables) to achieve a fit with these contingency factors (as context variables) to achieve more sustainable and flexible supply chains (as performance) (see: Sousa & Voss, 2008).

Gap 7: To identify the specificities of emerging economies context, to explore how firms adjust their strategies and practices to cope with such specificities, and to assess the resulting flexibility and sustainability performance.

Further comparison of the two contexts shows that in emerging economies, FGSCM strategies are often adopted only when they promise financial returns and are more likely to be abandoned if they fail in doing so (Esfahbodi et al., 2016), making proactive green strategy adoption less prevalent in emerging economies. Moreover, flexible reverse logistics, waste management, and green/flexible design were found to be the least developed strategies in emerging economies. The literature of FGSCM in developed countries can provide valuable insights for these areas.

As for other strategies, while present in both contexts, the implementation shows disparities. Customer collaboration in emerging economies leads to a stronger impact on environmental performance, as compared to supplier collaboration. Yet, studies on customer sustainability awareness in emerging economies are scarce. This motivates future research to explore strategies that improve customer collaboration and awareness in emerging economies. Furthermore, while research in developed countries indicates the positive impact of emerging technologies such as blockchain or industry 4.0 on FGSCM (Saberi et al., 2019), our review found no studies on the adoption of these technologies in emerging economies.

Gap 8: To study how to customize or transfer benchmark strategies and practices of flexible reverse logistics, waste management, and green/flexible design from developed countries to emerging economies.

Gap 9: To identify the strategies that improve customer collaboration and awareness in emerging economies and evaluate their impact on the flexibility and sustainability performance of firms.

Gap 10: To investigate the impact of emerging technologies and concepts such as blockchain, industry 4.0, 3D printing, and big data on FGSCM in emerging economies

Institutional Pressures

Identifying the sources of pressures on organizations that cause drivers or barriers on the path of FGSCM help managers to harness these pressures for mainstreaming FGSCM in emerging economies. The analysis presented in Tables 4 and 5 reveals more drivers and barriers related to the internal environment of firms, indicating that the (lack of) internal organizational support is an overriding (barrier) driver. This is in accordance with the findings of Jabbour et al. (2020) who expressed that company owners and shareholders are the most salient stakeholders to drive FGSCM in emerging economies. Little research, however, exists on the organizational functions and their impact on FGSCM in emerging economies.

Gap 11: To investigate the internal organizational factors, from a functional perspective, that impact the adoption of FGSCM strategies and practices in emerging economies

By taking an institutional theory lens, this review identified coercive pressures from government and regulations as powerful sources of compliance. However, fewer drivers and barriers related to coercive pressures were found, compared to the ones related to mimetic and normative pressures. This is notwithstanding the findings of Jayaram and Avittathur (2015) but is in line with Jabbour et al. (2020) about FGSCM-related coercive pressures in emerging economies.

Our findings suggests that business firms in emerging economies increasingly earn legitimacy by copying successful FGSCM strategies and practices of other firms (mimetic isomorphism) or due to customer and market pressures (normative isomorphism). It can imply that FGSCM in emerging economies is moving from mere compliance with regulations (coercive isomorphism) as firms are under increasing pressures by competitors and customers to gain legitimacy and market sustainability through FGSCM strategies and practices.

Gap 12: To study the institutional pressures emanating from customers and competitors driving/impeding FGSCM strategies and practices in emerging economies

Developing a Research Framework of FGSCM in Emerging Economies

Developing research frameworks for flexible or sustainable SCM has been at the center of scholars’ attention as these frameworks synthesize and illustrate the status quo and future directions in a concise and visualized, yet inclusive, manner. Some examples of such research frameworks are, inter alia, Seuring and Müller (2008), Sarkis et al. (2011), Dubey et al. (2015), Rajeev et al. (2017), Liao (2020), and Carter et al. (2021). However, our survey of the literature shows the paucity of combined flexible and sustainable SCM frameworks in the context of emerging economies. Hitherto, extant research frameworks focused merely on one aspect of FGSCM in emerging economies such as barriers and enablers (see Delmonico et al., 2018; Rahman et al., 2019; Tumpa et al., 2019), or investigated the impact of FGSCM strategies and practices on environmental performance (e.g., Esfahbodi et al., 2016; Geng et al., 2017a, 2017b; Luthra & Mangla, 2018). The literature scants research frameworks that firstly delve into the specificities of emerging economies vis-à-vis combined flexible and sustainable SCM, and secondly inclusively synthesize strategies and practices, as well as drivers and barriers.

Our proposed research framework addresses these shortcomings. Firstly, it not only synthesizes FGSCM strategies and practices in emerging economies, but also it discerns the specificities of emerging economies using the contingency theory lens (Table 3). This helps managers and decision-makers to account for the contextual differences in emerging economies when devising their organizational strategies and practices. Secondly, the literature advocates that institutional pressures in emerging economies to adopt FGSCM strategies and practices are significantly different in emerging economies from developed countries (Raj et al., 2022). We have classified the identified drivers and barriers found from our systematic review, based on the source of pressure they originate using the institutional theory perspective (Tables 4 and 5). This classification deepens the understanding of policymakers about the institutional pressures in emerging economies and allows them to harness these pressures appropriately to promote FGSCM. Resulting from these observations, the research framework directs scholars to future research by identifying the main research gaps in the literature. The research framework is presented in Fig. 9.

Conclusion

Emerging economies are prime targets of global businesses and multinational corporations for the outsourcing of manufacturing while the in-house operations that satisfy domestic demand in these countries are also seeing sharp growth (Jayaram & Avittathur, 2015). This paper reviewed the literature within the past 20 years and proposed a strategic research framework of FGSCM in emerging economies to address the increasing pressures from different stakeholders and calls from scholars to study FGSCM in emerging economies.

The study set out a systematic literature review to identify the status quo of research on the topic. The methodology is novel in that it combines a systematic literature review, text mining, and network analysis to explore, analyze, and synthesize knowledge gaps in the research domain. The applied inclusion and exclusion criteria, brainstorming sessions and crosschecks applied in consecutive steps contributed toward the selection quality of shortlisted articles and their subsequent analysis by limiting subjective biasness (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009). Text mining and network analysis of selected articles facilitated identifying networks of research articles dealing with particular aspects of FGSCM strategies and practices and showed that the extant empirical research articles in the research domain are fragmented.

Two grand organizational theories were employed: contingency theory to distinguish the specificities of emerging economies context, and institutional theory to discern the sources of pressures on institutions that facilitate or hinder FGSCM in emerging economies. Using contingency theory revealed that contextual specificities reduce the slope of FGSCM in emerging economies and using institutional theory revealed that coercive pressures from governments and regulations are powerful sources of compliances.

Finally, a research framework was developed to synthesize the extant literature and to identify the research gaps to inspire future research. This framework will help managers and decision-makers to understand the contextual differences in emerging economies while planning their organizational strategies and practices. Furthermore, the classification of drivers and barriers deepens the understanding of policy makers about the institutional pressures in the emerging economies allowing them to promote FGSCM.

This study is not devoid of limitations; firstly, the systematic literature review did not include studies with a mere focus on social sustainability. Higher prevalence of issues such as worker exploitation, unfair wages, substandard working environment, gender discrimination, and child labor in emerging economies are imperative avenues for future research. Secondly, the systematic literature review was restricted to the period of 2000–2020, to four academic databases, and to the research published in English. Some more important articles might exist outside our search boundaries.

References

Abraham, T., & Dao, V. T. (2019). A longitudinal exploratory investigation of innovation systems and sustainability maturity using case studies in three industries. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 32(4), 668–687.

Adhikari, A., & Bisi, A. (2020). Collaboration, bargaining, and fairness concern for a green apparel supply chain: An emerging economy perspective. Transportation Research Part E, 135, 1–23.

Albort-Morant, G., Leal-Millán, A., & Cepeda-Carrión, G. (2016). The antecedents of green innovation performance: A model of learning and capabilities. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 4912–4917.

Ansari, Z. N., & Kant, R. (2017). Exploring the framework development for sustainability in Supply chain management: A systematic literature synthesis and future research directions: Sustainable supply chain management framework. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(7), 873–892.

Bai, C., & Sarkis, J. (2010). Integrating sustainability into supplier selection with grey system and rough set methodologies. International Journal of Production Economics, 124(1), 252–264.

Balaji, M., Velmurugan, V., & Manikanda, P. K. (2014). Barriers in green supply chain management: An Indian foundry perspective. International Journal of Research Engineering and Technology, 03, 423–429.

Balon, V., Sharma, A. K., & Barua, M. K. (2016). Assessment of barriers in green supply chain management using ISM: A case study of the automobile industry in India. Global Business Review, 17, 116–135.

Basaglia, S., Caporarello, L., Magni, M., & Pennarola, F. (2009). Environmental and organizational drivers influencing the adoption of VoIP. Information Systems and e-Business Management, 7(1), 103–118.

Bhateja, A. K., Babbar, R., Singh, S., & Sachdeva, A. (2011). Study of green supply chain management in the Indian manufacturing industries: A literature review cum an analytical approach for the measurement of performance. International Journal of Computational Engineering and Management, 13, 84–99.

Bhool, R., & Narwal, M. S. (2013). An analysis of drivers affecting the implementation of green supply chain management for the Indian manufacturing industries. International Journal of Reserch in Engineering and Technology, 2, 242–254.

Bin Makhashen, Y., Rafi-ul-Shan, P. M., Bashiri, M., Hasan, R., Amar, H., & Khan, M. N. (2020). Exploring the role of ambidexterity and coopetition in designing resilient fashion supply chains: A multi-evidence-based approach. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 33(6), 1599–1625.

Birko, S., Dove, E. S., & Özdemir, V. (2015). Evaluation of nine consensus indices in Delphi foresight research and their dependency on Delphi survey characteristics: A simulation study and debate on Delphi design and interpretation. PLoS ONE, 10(8), 0135162.

Butt, A. S. (2021). Understanding the implications of pandemic outbreaks on supply chains: An exploratory study of the effects caused by the COVID-19 across four South Asian Countries and steps taken by firms to address the disruptions. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistic Management, 52(4), 370–392.

Cankaya, S., and Sezen, B. (2019). Effects of green supply chain management practices on sustainability performance. Journal Manufacturing Technology Management, 30(1), 98–121

Carter, T. R., Benzie, M., Campiglio, E., Carlsen, H., Fronzek, S., Hild´en, M., Reyer, C.P.O. and West, C. (2021). A conceptual framework for cross-border impacts of climate change. Global Environmental Change, 69.

Chan, H. K., He, H., & Wang, W. Y. C. (2012). Green marketing and its impact on supply chain management in industrial markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 41, 557–562.

Chan, H. K., Yee, R. W. Y., Dai, J., & Lim, M. K. (2016). The moderating effect of environmental dynamism on green product innovation and performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 181(22), 383–391.

Chen, L., Tang, O., & Feldmann, A. (2015). Applying GRI reports for the investigation of environmental management practices and company performance in Sweden, China And India. Journal of Cleaner Production, 98, 36–46.

Chiou, T., Chan, H. K., Lettice, F., & Chung, S. H. (2011). The influence of greening the suppliers and green innovation on environmental performance and competitive advantage in Taiwan. Transportation Research Part e: Logistics and Transportation Review, 47(6), 822–883.

Cosimato, S., & Troisi, O. (2015). Green supply chain management. TQM Journal, 27, 256–276.

Coughlan, P., & Coghlan, D. (2002). Action research for operations management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management., 22, 220–240.

Delmonico, D., Jabbourb, C. J. C., Pereirac, S. C. F., Jabbourb, A. B. L. D. S., Renwickd, D. W. S., & Thomée, A. M. T. (2018). Unveiling barriers to sustainable public procurement in emerging economies: Evidence from a leading sustainable supply chain initiative in Latin America. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 134, 70–79.

Denyer, D., Tranfield, D., (2009). Producing a systematic review. In The Sage Handbook of Organisational Reserch Methods, (pp. 671- 689).

Dhull, S., & Narwal, M. S. (2016). Drivers and barriers in green supply chain management adaptation: A state-of-art review. Uncertain Supply Chain ManagEment, 4, 61–76.

Dhull, S., & Narwal, M. S. (2018). Prioritizing the drivers of green supply chain management in Indian manufacturing industries using fuzzy TOPSIS method: Government, industry, environment, and public perspectives. Process Integration and Optimization for Sustainability, 2, 47–60.

Diab, S. M., Al-bourini, F. A., & Abu-rumman, A. H. (2015). The impact of green supply chain management practices on organizational performance: A study of Jordanian food industries. Journal of Management and Sustanablity, 5, 149–157.

Diabat, A., & Govindan, K. (2011). An analysis of the drivers affecting the implementation of green supply chain management. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 55(6), 659–667.

Diabat, A., Kannan, D., & Mathiyazhagan, K. (2014). Analysis of enablers for implementation of sustainable supply chain management - a textile case. Journal of Cleaner Production, 83, 391–403.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48, 147–160.

Dube, A. S., & Gawande, R. S. (2016). Analysis Of green supply chain barriers using integrated ISM-Fuzzy MICMAC approach. Benchmarking an International Journal, 23, 1558–1578.

Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., & Ali, S. S. (2015a). Exploring the relationship between leadership, operational practices, institutional pressures and environmental performance: A framework for green supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics., 160, 120–132.

Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., Papadopoulos, T., Childe, S. J., Shibin, K. T., & Wamba, S. F. (2017). Sustainable supply chain management: Framework and further research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 142, 1119–1130.

Dwivedi, A., Agrawal, D., Jha, A., Gastaldi, M., Paul, S. K., & D’Adamo, I. (2021). Addressing the challenges to sustainable initiatives in value chain flexibility: Implications for Sustainable Development Goals. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22(Suppl. 2), S179–S197.

Elliott, R. (2013). The taste for green: The possibilities and dynamics of status differentiation through “green” consumption. Poetics, 41(3), 294–322.

Epoh, L. R., & Mafini, C. (2018). Green supply chain management in small and medium enterprises: Further empirical thoughts from South Africa. Journal of Transportation and Supply Chain Managment, 12, 1–12.

Esfahbodi, A., Zhang, Y., & Watson, G. (2016). Sustainable supply chain management in emerging economies: Trade-offs between environmental and cost performance. International Journal of Production Economics., 181, 350–366.

Fahimnia, B., Sarkis, J., & Davarzani, H. (2015b). Green supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Production Economics, 162, 101–114.

Fang, C., & Zhang, J. (2018). Performance of green supply chain management: A systematic review and meta analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 183, 1064–1081.

Feng, T., Cai, D., Wang, D., & Zhang, X. (2016a). Environmental management systems and financial performance: The joint effect of switching cost and competitive intensity. Journal of Cleaner Production, 113(2), 781–791.

Feng, X., Fu, B., Piao, S., Wang, S., Ciais, P., Zeng, Z., Lu, Y., Zeng, Y., Li, Y., Jiang, X., & Wu, B. (2016b). Revegetation in China’s Loess Plateau is approaching sustainable water resource limits. Nature Climate Change, 6(11), 1019–1022.

Ferreira, M. A., Jabbour, C. J. C., & Jabbour, D. S. B. L. (2017). Maturity levels of material cycles and waste management in a context of green supply chain management: An innovative framework and its application to Brazilian Cases. The Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 19(1), 516–525.

Gan, T.-S., Steffan, M., Grunow, M., & Akkerman, R. (2021). Concurrent design of product and supply chain architectures for modularity and flexibility: Process, methods, and application. International Journal of Production Research, 60, 2292–2311.

Ganapathy, S. P., Natarajan, J., Gunasekaran, A., & Subramanian, N. (2014). Influence of eco-innovation on Indian manufacturing sector sustainable performance. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 21(3), 198–209.

Gandhi, S., Kumar, S., Kumar, P., & Kumar, D. (2015). Evaluating factors in implementation of successful green supply chain management using DEMATEL: A case study. International Strategic Management Review, 3, 96–109.

Garcia-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano, C., & van der Meer, Y. (2022). A theoretical framework for circular processes and circular impacts through a comprehensive review of indicators. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 23(2), 291–314.

Gavronski, I., Klassen, R. D., Vachon, S., & Nascimento, L. (2011). A resource-based view of green supply management. Transportation Research Part e: Logistics and Transportation Review, 47(6), 872–885.

Geng, R., Mansouri, A., & Aktas, E. (2017b). The relationship between green supply chain management and performance: A meta-analysis of empirical evidences in Asian emerging economies. International Journal of Production Economics., 183, 245–258.

Geng, R., Mansouri, S. A., Aktas, E., & Yen, D. A. (2017a). The role of Guanxi in green supply chain management in Asia’s emerging economies: A conceptual framework. Industrial Marketing Management, 63, 1–17.

Gholami, R., Binti, A., Ramayah, T., & Molla, A. (2013). Senior managers’ perception on green information systems (IS) adoption and environmental performance: Results from a field survey. Information and Management, 50(7), 431–438.

Gopal, P. R. C., & Thakkar, J. (2016). Sustainable supply chain practices: An empirical investigation on Indian automobile industry. Production Planning & Control, 27(1), 49–64.

Gosling, J., et al. (2016). The role of supply chain leadership in the learning of sustainable practice: Toward an integrated framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 137, 1458–1469.

Govindan, K., Kaliyan, M., Kannan, D., & Haq, A. N. (2014). Barriers analysis for green supply chain management implementation in Indian industries using analytic hierarchy process. International Journal of Production Economics., 147, 555–568.

Govindan, K., Kannan, D., & Shankar, M. (2015). Evaluation of green manufacturing practices using a hybrid MCDM model combining DANP with PROMETHEE. International Journal of Production Research, 53, 6344–6371.

Govindan, K., Muduli, K., Devika, K., & Barve, A. (2016). Resources, conservation and recycling investigation of the influential strength of factors on adoption of green supply chain management practices: An Indian mining scenario. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 107, 185–194.

Green, K. W., Pamela, J., Jeramy, J. Z., & Vikram, M. (2012). Green supply chain management practices: Impact on performance. Supply Chain Mangement: an International Journal, 17, 290–305.

Gunasekaran, A., & Spalanzani, A. (2012). Sustainability of manufacturing and services: Investigations for research and applications. International Journal of Production Economics, 140(1), 35–47.

Gupta, S., Drave, V. A., Bag, S., & Luo, Z. (2019). Leveraging smart supply chain and information system agility for supply chain flexibility. Information Systems Frontiers, 21, 547–564.

Hamzaoui Essoussi, L., & Linton, J. D. (2010). New or recycled products: How much are consumers willing to pay? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 27(5), 458–468.

Herring, H. (2006). Energy efficiency—a critical view. Energy, 31(1), 10–20.

Hsu, C. W., Kuo, T. C., Chen, S. H., & Hu, A. H. (2013). Using DEMATEL to develop a carbon management model of supplier selection in green supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 56, 164–172.

Huang, J.-W., & Li, Y.-H. (2017). Green innovation and performance: The view of organizational capability and social reciprocity. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(2), 309–324.

Hultman, N. E., Pulver, S., Guimaraes, L., Deshmukh, R., & Kane, J. (2012). carbon market risks and rewards: Firm perception of CDM investment decisions in Brazil and India. Energy Policy, 40, 90–102.

Jabbour, A., Jabbour, C., Hingley, M., Vilalta-Perdomo, E., Ramsden, G., & Twigg, D. (2020). sustainability of supply chains in the Wake of the coronavirus (COVID-19/SARS-Cov-2) pandemic: Lessons and trends. Modern Supply Chain Research and Applications., 2(3), 2631–3871.

Jabbour, C. J. C., & Jabbour, A. B. L. (2016). Green human resource management and green supply chain management: Linking two emerging agendas. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 1824–1833.

Jaikumar, G., Karpagam, M., & Thiyagarajan, S. (2013). Factors influencing corporate environmental performance in India. Indian Journal of Corporate Governance, 6(1), 2–17.

Jakhar, S. K., Rathore, H., & Mangla, S. K. (2018). ‘Is lean synergistic with sustainable supply chain? An empirical investigation from emerging economy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 139, 262–269.

Jawaad, M., & Zafar, S. (2019). Improving sustainable development and firm performance in emerging economies by implementing green supply chain activities. Sustainable Development, 28, 25–38.

Jawaad, M., & Zafar, S. (2020). Improving sustainable development and firm performance in emerging economies by implementing green supply chain activities. Sustainable Development, 28, 25–38.

Jayaram, J., & Avittathur, B. (2015). Green supply chains: A perspective from an emerging economy. International Journal of Production Economics, 164, 234–244.

Jayaraman, V., Singh, R., & Anandnarayan, A. (2012). impact of sustainable manufacturing practices on consumer perception and revenue growth: An emerging economy perspective. International Journal of Production Research, 50(1), 1395–1410.

Jia, F., Zuluaga-cardona, L., Bailey, A., & Rueda, X. (2018). Sustainable supply chain management in developing countries: An analysis of the literature. Journal of Cleaner Production, 189, 263–278.

Jia, P., Diabat, A., & Mathiyazhagan, K. (2015). Analyzing the SSCM practices in the mining and mineral industry by ISM approach. Resources Policy, 46, 76–85.

Khan, S.A.R. and Dong, Q. (2017) ‘The Environmental Supply Chain Management and the Companies’ Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Conference on Social Science and Higher Education. Atlantis Press, pp. 125–129.

Kleindorfer, P. R., Singhal, K., & Wassenhove, L. N. V. (2005). Sustainable operations management. Production and Operation Management, 14, 482–492.

Koh, S. C. L., Ganesh, K., Chidambaram, N., & Anbuudayasankar, S. P. (2012). Assessment on the adoption of low carbon and green supply chain management practices in Indian supply chain sectors – manufacturing and service industries. International Journal of Business and Globalization, 9(3), 311–345.

Kumar, N., Agrahari, R. P., & Roy, D. (2015). Review of green supply chain processes. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 48(3), 374–381.

Kumar, S., Govindan, K., & Luthra, S. (2016). Critical success factors for reverse logistics in Indian industries: A structural model. Journal of Cleaner Production, 129, 608–621.

Kumar, V., Jabarzadeh, Y., Jeihouni, P., & Garza-reyes, J. A. (2020). Learning orientation and innovation performance: The mediating role of operations strategy and supply chain integration. Supply Chain Management- an International Journal, 4, 457–474.

Lai, K., & Wong, C. W. Y. (2012). Green logistics management and performance: Some empirical evidence from Chinese manufacturing exporters. Omega, 40, 267–282.

Laosirihongthong, T., Adebanjo, D., & Tan, K. (2013). Green supply chain management practices and performance. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 113(8), 1088–1109.

Lawrence, P., & Lorsch, J. (1967). Differentiation and integration in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12, 1–47.

Lee, S. Y. (2015). The effects of green supply chain management on the supplier’s performance through social capital accumulation. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 20(1), 42–55.

Li, S., Jayaraman, V., Paulraj, A., & Shang, K. C. (2015). Proactive environmental strategies and performance: role of green supply chain processes and product design in the Chinese high-tech industry. International Journal of Production Research, 54, 2136–2151.

Liao, Y. (2020). An integrative framework of supply chain flexibility. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 69(6), 1321–1342.

Liu, Y., Zhu, Q., & Seuring, S. (2017). Linking capabilities to green operations strategies: The moderating role of corporate environmental proactivity. International Journal of Production Economics, 187, 182–195.

Lorek, S., & Spangenberg, J. H. (2014). Sustainable consumption within a sustainable economy – beyond green growth and green economies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 63, 33–44.

Luken, R., & Stares, R. (2005). Small business responsibility in developing countries: A threat or an opportunity? Business Strategy and the Environment, 14, 38–53.

Luthra, S., Garg, D., & Haleem, A. (2015a). An analysis of interactions among critical success factors to implement green supply chain management towards sustainability: An Indian perspective. Resources Policy, 46, 37–50.

Luthra, S., Garg, D., & Haleem, A. (2015b). An analysis of interactions among critical success factors to implement green supply chain management towards sustainability: An Indian perspective. Resource Policy, 46, 37–50.

Luthra, S., Garg, D., & Haleem, A. (2016). the impacts of critical success factors for implementing green supply chain management towards sustainability: An empirical investigation of Indian automobile industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 121, 142–158.

Luthra, S., Garg, D., & HaleemA,. (2015c). Critical success factors of green supply chain management for achieving sustainability in Indian automobile industry. Production Planning and Control, 26, 339–362.

Luthra, S., & Mangla, S. (2018). Evaluating challenges to Industry 4.0 initiatives for supply chain sustainability in emerging economies. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 117, 168–179.

Majumdar, A., & Sinha, S. K. (2019). Analyzing the barriers of green textile supply chain management in Southeast Asia using interpretive structural modeling. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 17, 176–187.

Malviya, R. K., & Kant, R. (2015). Green supply chain management (GSCM): A structured literature review and research implications. Benchmarking-an International Journal, 22, 1360–1394.

Mangla, S. K., Govindan, K., & Luthra, S. (2016). Critical success factors for reverse logistics in Indian industries: A structural model. Journal of Cleaner Production, 129, 608–621.

Mangla, S. K., Kumar, P., & Barua, M. K. (2015). Risk analysis in green supply chain using fuzzy AHP approach: A case study. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 104, 375–390.

Mansi, M. (2015). Sustainable procurement disclosure practices in central public sector enterprises: Evidence from India. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, Elsevier, 21(2), 125–137.

Maric, J., & Opazo-basaez, M. (2019). Green servitization for flexible and sustainable supply chain operations: A review of reverse logistics services in manufacturing. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 20, S65–S80.

Martín-Gómez, A., Aguayo-González, F., & Luque, A. (2019). A holonic framework for managing the sustainable supply chain in emerging economies with smart connected metabolism. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 141, 219–232.

Mathiyazhagan, K., Datta, U., Bhadauria, R., Singla, A., & Krishnamoorthi, S. (2018). Identification and prioritization of motivational factors for the green supply chain management adoption: Case from Indian construction industries. Opsearch, 55, 202–219.

Mathiyazhagan, K., Diabat, A., Al-Refaie, A., & Xu, L. (2015). Application of analytical hierarchy process to evaluate pressures to implement green supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 107, 229–236.

Mathiyazhagan, K., Govidan, K., & Haq, A. N. (2014). Pressure analysis for green supply chain management implementation in Indian industries using analytic hierarchy process. International Journal of Production Research, 52, 188–202.

Mathiyazhagan, K., & Haq, A. N. (2013). Analysis of the influential pressures for green supply chain management adoption—an Indian perspective using interpretive structural modeling. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 68, 817–833.

Mathiyazhagan, K., Haq, A. N., & Baxi, V. (2016). Analysing the barriers for the adoption of green supply chain management – the Indian plastic industry perspective. International Journal of Business Performance and Supply Chain Modelling, 8, 46–65.

Mhelembe, K., & Mafini, C. (2019). Modelling the link between supply chain risk, flexibility and performance in the public sector. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 22(1), 1–12.

Mitra, S., & Datta, P. P. (2014). Adoption of green supply chain management practices and their impact on performance: An exploratory study of Indian manufacturing firms. International Journal of Production Research, 52(7), 2085–2107.

Mobley, A. S., Painter, T. S., Untch, E. M., & Unnavav, R. H. (1995). Consumer evaluation of recycled products. Psychology and Marketing, 12(3), 165–176.

Mohanty, R. P., & Prakash, A. (2014). Green supply chain management practices in India: A confirmatory empirical study. Production & Manufacturing Research, 2(1), 438–456.

Muduli, K., Govindan, K., Barve, A., & Geng, Y. (2013). Barriers to green supply chain management in Indian mining industries: A graph theoretic approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 47, 335–344.

Mumtaz, U., et al. (2018). Identifying the critical factors of green supply chain management: Environmental benefits in Pakistan. Science of the Total Environment, 640–641, 144–152.

Munguia, N., Zavala, A., & Marin, A. (2010). Identifying pollution prevention opportunities in the Mexican auto refining industry. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 21(3), 324–335.

Nema, N., Nougriaya, M., Soni, M., & Talankar, M. (2013). Green supply chain management practices in textile and apparel industries: Literature review. International Journal Commerce and Business Management, 1, 330–336.

Newbert, S. (2007). Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 121–146.

Nishitani, K. (2010). Demand for ISO 14001 adoption in the global supply chain: An empirical analysis focusing on environmentally conscious markets. Resource and Energy Economics, 32(3), 395–407.

Pakdeechoho, N., & Sukhotu, V. (2018). Sustainable supply chain collaboration: Incentives in emerging economies. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 29(2), 273–294.

Park, J., Sarkis, J., & Wu, Z. (2010). Creating integrated business and environmental value within the context of China’s circular economy and ecological modernization. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(15), 1494–1501.

Park, Y. R., Song, S., Choe, S., & Baik, Y. (2015). Corporate social responsibility in international business: Illustrations from Korean and Japanese electronics MNEs in Indonesia. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(3), 747–761.

Paul, S. K., & Chowdhury, P. (2020). Strategies for managing the impacts of disruptions during COVID-19: an example of toilet paper. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 21(3), 283–293.

Pinto, G. M. C., Pedroso, B., Moraes, J., Pilatti, L. A., & Picinin, C. T. (2018). Environmental management practices in industries of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) from 2011 to 2015. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 1251–1261.

Prasad, S., Khanduja, D., & Sharma, S. K. (2016). An empirical study on applicability of lean and green practices in the foundry industry. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 27(3), 408–426.

Quarshie, A. M., Salmi, A., & Leuschner, R. (2016). Sustainability and corporate social responsibility in supply chains: The state of research in supply chain management and business ethics. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 22, 82–97.

Rafi-Ul-Shan, P. M., Grant, D. B., Perry, P., & Ahmed, S. (2018). Relationship between sustainability and risk management in fashion supply chains: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 46, 466–486.

Rahman, T., Ali, S. M., Moktadir, M. A., & Kusi-Sarpong, S. (2019). Evaluating barriers to implementing green supply chain management: An example from an emerging economy. Production Planning and Control, 3(8), 673–698.

Raj, A., Mukherjee, A. A., de Sousa Jabbour, A., & Srivastava, S. K. (2022). Supply chain management during and post-COVID-19 pandemic: Mitigation strategies and practical lessons learned. Journal of Business Research, 142, 1125–1139.

Raj, T., Shankar, R., & Suhaib, M. (2008). An ISM approach for modelling the enablers of flexible manufacturing system: The case for India. International Journal of Production Economics, 46, 6883–6912.

Rajeev, A., Pati, R. K., Padhi, S. S., & Govindan, K. (2017). Evolution of sustainability in supply chain management: A literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 162, 299–314.

Rao, P., & Holt, D. (2005). Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? International Journal of Operationa and Production Management, 25, 898–916.

Rao, T. B., Chonde, S. G., Bhosale, P. R., Jadhav, A. S., & Raut, P. D. (2012). Environmental audit of distillery industry: A case study of Kumbhi Kasari Distillery Factory, Kuditre, Kolhapur. Nature Environment and Pollution Technology: An International Quarterly Scientific Journal, 11(1), 141–145.

Rathore, P., Kota, S., & Chakrabarti, A. (2011). Sustainability through remanufacturing in India: A case study on mobile handsets. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19(15), 1709–1722.

Raut, R. D., Narkhede, B., & Gardas, B. B. (2017). To identify the critical success factors of sustainable supply chain management practices in the context of oil and gas industries: ISM approach. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Review, 68, 33–47.

Rosin, F., et al. (2020). Impacts of industry 4.0 technologies on Lean principles. International Journal of Production Research, 58(6), 1644–1661.

Saberi, S., Kouhizadeh, M., & Sarkis, J. (2019). Blockchains and the supply chain: Findings from a broad study of practitioners. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 47, 95–103.

Sarker, S. K., Reeve, R., & Matthiopoulos, J. (2021). Solving the fourth-corner problem: Forecasting ecosystem primary production from spatial multispecies trait-based models. Ecological Monographs, 91(3), e01454.

Sarkis, J., Zhu, Q., & Lai, K. H. (2011). An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. International Journal of Production Economics, 130, 1–15.

Sassanelli, C., & Terzi, S. (2022). The D-BEST reference model: a flexible and sustainable support for the digital transformation of small and medium enterprises. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 23(3), 345–370.

Saunila, M., Ukko, J., & Rantala, T. (2018). Sustainability as a driver of green innovation investment and exploitation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 179, 631–641.

Scarpa, R., & Willis, K. (2010). Willingness-to-pay for renewable energy: Primary and discretionary choice of British households’ for micro-generation technologies. Energy Economics, 32(1), 129–136.

Scavarda, A., et al. (2019). A proposed healthcare supply chain management framework in the emerging economies with the sustainable lenses: The theory, the practice, and the policy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 141, 418–430.

Sen, P., Roy, M., & Pal, P. (2015). Exploring role of environmental proactivity in financial performance of manufacturing enterprises: A structural modelling approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 108, 583–594.

Sen, S. (2009). Linking green supply chain management and shareholder value creation. The IUP Journal of Supply Chain Management, 7(3), 95–109.

Settembre-Blundo, D., González-Sánchez, R., Medina-Salgado, S., & García-Muiña, F. E. (2021). Flexibility and resilience in corporate decision making: a new sustainability-based risk management system in uncertain times. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22(Suppl. 2), S107–S132.

Seuring, S., & Müller, M. (2008). From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16, 1699–1710.

Shibin, K. T., Gunasekaran, A., Papadopoulos, T., Dubey, R., Singh, M., & Wamba, S. F. (2016). Enablers and barriers of flexible green supply chain management: A total interpretive structural modeling approach. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 17, 171–188.

Shohan, S., et al. (2019). Green supply chain management in the chemical industry: Structural framework of drivers. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 26(8), 752–768.

Shukla, A. C., Deshmukh, S. G., & Kanda, A. (2009). Environmentally responsive supply chains: Learnings from the Indian auto sector. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 6(2), 154–171.

Silvestre, B. S. (2015). Sustainable supply chain management in emerging economies: Environmental turbulence, institutional voids and sustainability trajectories. International Journal of Production Economics, 167, 156–169.

Singh, R. K., & Acharya, P. (2013). Supply chain flexibility: A frame work of research dimensions. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 14(3), 157–166.

Singh, R. K., Acharya, P., & Modgil, S. (2020a). A template based approach to measure supply chain flexibility: A case study of Indian soap manufacturing firm- supply chain flexibility: A framework of research dimensions. Global Journal of Flexible System Management, 14(3), 157–166.

Singh, R. K., Modgil, S., & Acharya, P. (2019). Assessment of flexible supply chain using system dynamics modelling: A case of Indian soap manufacturing firm. Global Journal of Flexible System Management, 20(1), 39–63.

Singh, R. K., Modgil, S., & Acharya, P. (2020b). Identification and causal assessment of supply chain flexibility. Benchmarking: an International Journal, 27(2), 517–549.

Soda, S., Sachdeva, A., & Garg, R. K. (2015). GSCM: Practices, trends and prospects in Indian context. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 26(6), 889–910.

Soundararajan, V., & Brown, J. A. (2016). Voluntary governance mechanisms in global supply chains: Beyond CSR to a stakeholder utility perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(1), 83–102.

Sousa, R., & Voss, C. A. (2008). Contingency research in operations management practices. Journal of Operations Management, 26(6), 697–713.

Srivastava, S. K. (2007). Green supply-chain management: A state-of-the-art literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 9, 53–80.

Stevenson, M., & Spring, M. (2007). Flexibility from a supply chain perspective: Definition and review. International Journal of Operation and Production Management, 27, 685–713.

Stiller, S., & Gold, S. (2014). Socially sustainable supply chain management practices in the Indian seed sector – a case study. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal, 5(1), 52–67.

Thun, J.-H., & Müller, A. (2010). An empirical analysis of green supply chain management in the German automotive industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 19(2), 119–132.

Touzi, B., Mabrouki, C., & Farchi, A. (2015). Green supply chain management practices in textile and clothing sector: Literature review. International Journal of Commerce, Business and Management (IJCBM), 4(4), 1229–1238.

Tukamuhabwa, B., Stevenson, M., & Busby, J. (2017). "Supply chain resilience in a developing country context: A case study on the interconnectedness of threats, strategies and outcomes. Supply Chain Managment, 22, 486–505.

Tumpa, T. J., Ali, S. M., Rahman, M. H., Paul, S. K., Chowdhury, P., & Rehman Khan, S. A. (2019). Barriers to green supply chain management: An emerging economy context. Journal of Cleaner Production, 236, 117617.

Vijayvargy, L., Thakkar, J., & Agarwal, G. (2017). Green supply chain management practices and performance: The role of firm-size for emerging economies. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 28, 299–323.

Wang, P., Liu, Q., & Qi, Y. (2014). Factors influencing sustainable consumption behaviors: A survey of the rural residents in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 63, 152–165.

Wang, Z., Mathiyazhagan, K., Xu, L., & Diabat, A. (2015). A decision making trial and evaluation laboratory approach to analyze the barriers to Green Supply Chain Management adoption in a food packaging company. Journal of Cleaner Production, 117, 19–28.

Wadhwa, S., & Rao, K. S. (2004). A unified framework for manufacturing and supply chain flexibility. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 5(1), 29–36.

Yadav, G., Luthra, S., Jakhar, S.K., Mangla, S.K., Rai, D.P., (2020) A framework to overcome sustainable supply chain challenges through solution measures of industry 4.0 and circular economy: An automotive case. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 254.

Yildiz Çankaya, S., & Sezen, B. (2019). Effects of green supply chain management practices on sustainability performance. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 30(1), 98–121.

Young, W., Hwang, K., McDonald, S., & Oates, C. J. (2010). Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustainable Development, 18(1), 20–31.

Younis, H., Sundarakani, B., & Vel, P. (2016). The impact of implementing green supply chain management practices on corporate performance. Competitiveness Review, 26(3), 216–245.

Yu, K., Cadeaux, J., & Luo, B. (2015). Operational flexibility: review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Production Economics, 169, 190–202.

Yu, W., & Ramanathan, R. (2015). An empirical examination of stakeholder pressures, green operations practices and environmental performance. International Journal of Production Research, 53(21), 6390–6407.

Zailani, S., Jeyaraman, K., Vengadasan, G., & Premkumar, R. (2012). Sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) in Malaysia: A survey. International Journal of Production Economics, 140(1), 330–340.

Zarei, M. H., Carrasco-Gallego, R., & Ronchi, S. (2019). To greener pastures: An action research study on the environmental sustainability of humanitarian supply chains. International Journal of Operations & Production Management., 39, 1193–1225.

Zhang, D., Rong, Z., & Ji, Q. (2019). Green innovation and firm performance: Evidence from listed companies in China. Resource, Conservation and Recycling, 144, 48–55.

Zhang, G., & Zhao, Z. (2012). Green packaging management of logistics enterprises. Physics Procedia, 24, 900–905.

Zhu, G., Geng, Y., & Lai, K. (2010). Circular economy practices among Chinese manufacturers varying in environmental-oriented supply chain cooperation and the performance implications. Journal of Environmental Management, 91(6), 1324–1331.

Zhu, Q., & Sarkis, J. (2004). Relationships between operational practices and performance among early adopters of green supply chain management practices in Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Journal of Operations Management, 22(3), 265–289.

Zhu, Q., & Sarkis, J. (2006). An inter-sectoral comparison of green supply chain management in China: Drivers and practices. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(5), 472–486.

Zhu, Q., & Sarkis, J. (2016). Green marketing and consumerism as social change in China: Analyzing the literature. International Journal of Production Economics, 181, 289–302.

Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J., & Lai, K. (2007). Green supply chain management: Pressures, practices and performance within the Chinese automobile industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15(11–12), 1041–1052.

Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J., & Lai, K. (2008). Green supply chain management implications for closing the loop. Transportation Research Part E, 44, 1–18.

Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J., & Lai, K. H. (2013). Institutional-based antecedents and performance outcomes of internal and external green supply chain management practices. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 19(2), 106–117.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very thankful to all the associated personnel in any reference that contributed in/for the purpose of this research.

Funding

This research was not funded by any person neither by any public or private body.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dhillon, M.K., Rafi-Ul-Shan, P.M., Amar, H. et al. Flexible Green Supply Chain Management in Emerging Economies: A Systematic Literature Review. Glob J Flex Syst Manag 24, 1–28 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-022-00321-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-022-00321-0