Abstract

Introduction

Chronic ocular surface pain (COSP) is described as a persistent, moderate-to-severe pain at the ocular surface lasting more than 3 months. Symptoms of COSP have a significant impact on patients’ vision-dependent activities of daily living (ADL) and distal health-related quality of life (HRQoL). To adequately capture patient perspectives in clinical trials, patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures must demonstrate sufficient evidence of content validity in the target population. This study aimed to explore the patient experience of living with COSP and evaluate content validity of the newly developed Chronic Ocular Pain Questionnaire (COP-Q) for use in COSP clinical trials.

Methods

Qualitative, combined concept elicitation (CE) and cognitive debriefing (CD) interviews were conducted with 24 patients experiencing COSP symptoms in the USA. Interviews were supplemented with real-time data collection via a daily diary app task in a subset of patients (n = 15) to explore the day-to-day patient experience. Three healthcare professionals (HCPs) from the USA, Canada, and France were also interviewed to provide a clinical perspective. CE results were used to further inform development of a conceptual model and to refine PRO items/response options. CD interviews assessed relevance and understanding of the COP-Q. Interviews were conducted across multiple rounds to allow item modifications and subsequent testing.

Results

Eye pain, eye itch, burning sensation, eye dryness, eye irritation, foreign body sensation, eye fatigue, and eye grittiness were the most frequently reported symptoms impacting vision-dependent ADL (e.g., reading, using digital devices, driving) and wider HRQoL (e.g., emotional wellbeing, social functioning, work). COP-Q instructions, items, and response scales were understood, and concepts were considered relevant. Feedback supported modifications to instruction/item wording and confirmed the most appropriate recall periods.

Conclusions

Findings support content validity of the COP-Q for use in COSP populations. Ongoing research to evaluate psychometric validity of the COP-Q will support future use of the instrument in clinical trial efficacy endpoints.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

There is a lack of published research regarding the lived experience of chronic ocular surface pain (COSP), and existing patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments are not considered adequate for use in COSP clinical trials from a regulatory perspective (e.g., as required by the US Food and Drug Administration for the evaluation of new treatments). |

This study aimed to conduct qualitative research to understand the patient experience of COSP to support development and evaluate content validity of a new PRO instrument assessing COSP-related symptoms, impacts on vision-dependent activities, and broader health-related quality of life in adult populations. |

What was learned from the study? |

This study provides insight into the symptoms and impacts of COSP from both the patient and clinician perspective and provides evidence to support the face and content validity of the 22-item Chronic Ocular Pain Questionnaire (COP-Q) (with an alternative 7-item symptom module for assessment over 24 h). |

Ongoing research to evaluate the psychometric validity of the COP-Q will support future use of the instrument in clinical trials to derive efficacy endpoints. |

Introduction

Chronic ocular surface pain (COSP) is persistent, moderate-to-severe pain at the ocular surface lasting more than 3 months in the absence of other tissue injury [1,2,3]. It can include nociceptive, neuropathic, or inflammatory pain [3]. Numerous etiological processes may cause or exacerbate COSP, including ocular conditions (e.g., dry eye disease [DED], eyelid abnormalities), medical or surgical treatments (e.g., ocular surgeries, medications), neurological conditions (e.g., postherpetic neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia), autoimmune or inflammatory diseases (e.g., Sjögren’s syndrome, celiac disease), and environmental factors (e.g., humidity, temperature) [1]. No universal diagnostic criteria currently exist for COSP, making diagnosis challenging [2, 4] and hindering definitive incidence and prevalence data [1].

In addition to ocular pain, symptoms of COSP can include eye dryness, burning sensation, eye irritation, foreign body sensation, eye itch, and sensitivity to light [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Regardless of the descriptor, these sensations are all forms of pain that often becomes chronic and causes difficulties with vision-dependent activities of daily living (ADL), including reading, driving and computer function, as well as decreased occupational productivity and missed work, leading to significant impacts on physical, psychological, and social domains of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [6, 12, 13]. No treatments have been specifically approved for COSP, with current strategies mirroring pain management in other ophthalmic conditions [2, 6, 14]. Thus, there is an unmet need for targeted drug therapies to treat COSP symptoms.

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures can form clinical trial endpoints for new therapies, alongside other clinical endpoints. For a PRO to be considered fit-for-purpose by regulatory agencies to support endpoints in clinical trials [15, 16], it must measure concepts that are clinically relevant and important to patients, with evidence of validity, reliability, and ability to detect change in the target population. While it is understood that COSP symptoms affect patients’ vision-dependent ADL and wider HRQoL, qualitative evidence of this in the literature is minimal and largely focused on patients with DED [6, 12]. A review of the literature performed in 2019 identified the Ocular Pain Assessment Survey (OPAS) [17], the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) [18], the Quality of Vision (QoV) questionnaire [19], the Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL) [20], the Neuropathic Pain Syndrome Inventory in individuals with eye pain (NPSI-Eye) [21], the Symptom Assessment Questionnaire in Dry Eye (SANDE) [22], the Dry Eye-Related Quality-of-Life Score (DEQS) [23], and the Visual Function Questionnaire (VFQ-25) [24], as existing PROs that could potentially be used to assess COSP symptoms and their impact on HRQoL. Of the existing measures, while several are strong measures assessing relevant concepts and may be valuable tools for assessing some aspects of COSP symptoms and functioning, none were considered optimal for use in the planned clinical trials in COSP to assess the target measurement concepts of interest. It was therefore decided to develop a new tool that was specifically focused on symptoms and quality of life for patients with COSP and that could be developed from the start based on qualitative research with patients with COSP of a range of etiologies. Further, some of these existing measures seemed unlikely to meet regulatory requirements [15, 16], or did not include items assessing all measurement concepts that were of interest. Some of them lacked sufficient evidence of patient involvement during development or had only been validated in patients with one type of ocular pain (e.g., DED, corneal pain). Conceptual coverage was also limited for some of the measures (e.g., assessment of symptom severity and comprehensive assessment of HRQoL impacts). Several PROs tended to employ recall periods unsuitable for symptom assessment in clinical trials (e.g., ‘last week’), which could introduce recall bias.

The overall objective of this study was to conduct qualitative research to better understand the patient experience of COSP and evaluate content validity of the newly developed Chronic Ocular Pain Questionnaire (COP-Q) and associated patient global impression (PGI) items for use in COSP populations, in line with current regulatory guidance [15, 16]. A second objective was to evaluate content validity of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire plus Classroom Impairment Questions (WPAI+CIQ) [25] to determine its suitability for use in future COSP clinical trials.

Methods

Study Design

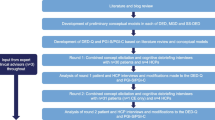

This was a qualitative study to develop a conceptual model and develop/evaluate a new PRO instrument suitable for use in COSP treatment trials. Combined concept elicitation (CE) and cognitive debriefing (CD) interviews were conducted with individuals from the USA with COSP symptoms to understand the patient experience and generate evidence for content validity of the COP-Q and associated PGI items. Interviews were also conducted with healthcare professionals (HCPs) from the USA, Canada, and France with experience treating patients with COSP symptoms to provide a clinical perspective. A subset of patients with COSP with moderate to severe symptoms also completed a real-time daily diary app task (DDAT) over 7 days to explore the day-to-day patient experience of COSP. Patient interviews and DDAT activities were conducted in two rounds to allow modifications to the COP-Q to be implemented between rounds and tested in the second round of interviews. Feedback from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was also sought between interview rounds. Further, to ensure clinical insight into the interpretation of study findings, two US-based clinical experts provided input at key stages throughout the research. Figure 1 provides an overview of the study design.

Instrument Development

Development of the draft conceptual model in COSP and draft COP-Q were informed by a targeted qualitative literature and blog review, along with an existing draft PRO measure developed to assess vision-dependent activities for use in DED (the Visual Tasking Questionnaire) and input from the expert clinical advisors. The initial version of the COP-Q (v1_0) consisted of four core modules to assess daily eye pain (2 items), COSP-related symptoms (8 items), impacts on vision-dependent activities (13 items), and wider HRQoL (5 items) (Table 1). Different response scales and recall periods were tested for the various modules (in core and alternative versions) with the aim of selecting the most appropriate option from the patient perspective. Patient Global Impression of Severity (PGI-S) and Patient Global Impression of Change (PGI-C) items were also developed to support anchor-based meaningful change analyses in future COSP clinical studies.

Qualitative Interviews and DDAT

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval and oversight were provided by Western Copernicus Group Independent Review Board (WCG IRB, reference: 1284816), a centralized IRB, to conduct qualitative interviews and daily diary app task activity in the USA. All participants provided oral and written informed consent prior to the conduct of any research activities. The research was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments.

Sample and Recruitment

Third-party recruitment agencies were used to recruit patients via referring clinicians and patient advocacy groups. HCPs confirmed the patient’s eligibility (Table 2) and provided background clinical information by completing a case report form (CRF). All patients completed an informed consent form (ICF) prior to any study-related activities. A target of 24 patient interviews (with 15 completing the DDAT) was expected to be sufficient for achieving ‘concept saturation’: the point at which no new concept-relevant information is likely to emerge with further interviews [26, 27]. Target sampling quotas were employed to ensure a range of clinical and demographic characteristics were represented. Three HCPs were also recruited to provide a clinical perspective. HCPs were identified via the authors’ networks and review of author lists of relevant publications. All participants were compensated for their participation.

Interview Procedure

All interviews were conducted via telephone by trained qualitative interviewers, using a semi-structured interview guide. Patient interviews lasted approximately 75 min and HCP interviews were approximately 60 min.

The CE portion of the patient and HCP interviews started with broad, open-ended questions to facilitate spontaneous elicitation of concepts regarding the patient experience of COSP. Focused questions were then used if concepts of interest had not emerged or been fully explored.

For the CD section, patients were asked to complete the COP-Q and PGI-S/PGI-C items on paper using a ‘think aloud’ approach in which they were asked to share their thoughts as they read each instruction/item and selected each response. Patients were then asked detailed questions about their interpretation and understanding of instruction/item wording, relevance of concepts, and appropriateness of response options and recall periods. Alongside the COP-Q, patients were also debriefed on the WPAI+CIQ to confirm its relevance in a COSP population (see Supplementary Materials Supplementary 1 for more detail on methods). Due to time limitations during the interviews, it was expected that at least half the patient sample (n = 12) would debrief each module. HCPs were similarly provided with a copy of the COP-Q and asked to provide feedback on the clinical relevance of each item and appropriateness of item wording, response options, and recall periods.

DDAT Procedure

For the DDAT, patients were asked to respond to daily tasks using a smartphone application. The tasks asked patients to submit short video/audio clips, images/photographs, and/or text responses to describe their experience with ocular pain over a 7-day period (see ESM file 2 for DDAT script). This approach enabled real-time insights to be captured while patients were experiencing (or shortly thereafter) COSP symptoms or impacts. To support interpretation, patients were asked to rate the severity of their ocular pain on a 0–10 numeric rating scale (NRS) daily, and to indicate whether they had taken any prescribed medication to alleviate their pain. Patients who also participated in an interview completed the DDAT prior to their scheduled interview. Of note, only patients with moderate to severe COSP were invited to take part in the DDAT; patients with mild symptoms were not included in this part of the study since COSP is considered to be moderate to severe pain, and patients with mild symptoms are not typically targeted for inclusion in clinical trials.

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, with identifiable information redacted. Transcripts of DDAT entries were also produced. The CE section of the interview transcripts and DDAT entries were subject to thematic analysis using Atlas.Ti (version 8) [28]. Participant quotes pertaining to symptoms and impacts of COSP were assigned corresponding concept codes in accordance with an agreed coding scheme. Codes were applied both deductively (based on prior knowledge) and inductively (as emerging from the data).

Concept saturation analysis was conducted on the patient CE interviews to ensure data collection was exhaustive. Transcripts were chronologically grouped into three equal sets, and spontaneously reported symptom and impact concepts emerging from each set were iteratively compared. Saturation was deemed achieved if no new concept-relevant information emerged in the final set of interviews [27, 29].

The CD section of the patient transcripts was analyzed using dichotomous codes that were assigned to each item, instruction, response option(s), and recall period to indicate whether it was understood and relevant. Suggested changes were also coded. For the HCP transcripts, codes were assigned to instrument feedback (e.g., missing/relevant concepts, likes/dislikes).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Patient Characteristics

Overall, 24 patients were interviewed for the study, of whom 13 participated in the DDAT. To meet target quotas, two additional patients (n = 2) were recruited for the DDAT, resulting in a total sample of 26 patients. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics were relatively diverse (Table 3).

HCP Characteristics

A total of three HCPs were interviewed from the USA (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), and France (n = 1). The demographic characteristics of these three HCPs are summarized in Table 4.

Concept Elicitation and DDAT

The findings from the literature review, CE portion of the patient and HCP interviews, and DDAT are summarized in a conceptual model, displaying the key concepts associated with COSP (Fig. 2).

Table 5 provides an overview of the key symptoms and impacts identified during the CE portion of the interviews and DDAT. Eight primary eye pain-related symptoms of COSP were reported across all data sources: eye pain, eye itch, a burning sensation, eye dryness, eye irritation, foreign body sensation, eye fatigue, and eye grittiness. Patients most frequently reported eye pain (n = 9/24, 37.5%) and a burning sensation (n = 7/24, 29.2%) as the most bothersome symptoms. Secondary symptoms were also reported including vision-related (e.g., light sensitivity, blurred vision) and physical symptoms (e.g., eye redness, inflammation), as displayed in Fig. 2.

During the interviews, several patients noted conceptual overlap in symptoms, the most frequent being between eye grittiness and foreign body sensation (n = 6/17, 35.3%) and eye irritation and a burning sensation (n = 6/17, 35.3%). Conceptual overlap between eye grittiness and foreign body sensation was also mentioned by two of the three HCPs. Most patients who were asked also reported that burning sensation (n = 16/20, 80.0%), eye dryness (n = 10/14, 71.4%), eye irritation (n = 11/17, 64.7%), and foreign body sensation (n = 9/15, 60.0%) were different aspects of eye pain, rather than distinct concepts. Findings from the DDAT indicated that severity of COSP symptoms varied day-to-day and that frequency and intensity of symptoms were highly variable across individuals. While some patients (n = 5) consistently reported mild-moderate pain-related symptoms, others (n = 3) reported experiencing more extreme fluctuations over the course of a week, ranging from pain-free days to days with severe pain. When describing this variation more generally, half of patients (n = 8/15) reported regular fluctuation in symptom severity, often referring to this as good versus bad days.

COSP symptoms were reported to have numerous functional impacts on ADL. Difficulty reading was the most reported daily life impact, with interviewed patients most frequently describing difficulty reading text on digital screens (n = 15/24, 62.5%) and in books (n = 13/24, 54.2%). Over half the DDAT sample (n = 8/15, 53.3%) suggested difficulty reading was the most bothersome impact. Impacts on using digital devices, including watching TV (n = 17/24, 70.8%) and working on a computer (n = 17/24, 70.8%), were also reported. Patients described avoiding or limiting use of digital devices due to their symptoms. COSP symptoms were also reported to impact patients’ ability to drive; most patients in the interviews described difficulty driving both during the day (n = 22/24, 91.7%) and at night (n = 21/24, 87.5%), although they noted that night-time driving was more challenging. Further, participants reported impacts on the ability to engage in sports/hobbies/leisure activities, with patients in the interviews most frequently reporting difficulty attending events (n = 18/24, 75.0%). Other daily life impacts included difficulty performing self-care activities and household chores and impacts on sleep (e.g., sleep quality and ability to sleep). The impact on ADL was reported to be related to symptom severity, with patients in both the interviews and DDAT consistently reporting being unable to do specific activities when pain was at its most severe. Impacts on distal HRQoL concepts were also identified, including impacts on emotional wellbeing (e.g., frustration/annoyance, depression/sadness, stress/worry), social functioning, and work and finances.

Concept Saturation

Saturation analysis highlighted that no further qualitative interviews were necessary since all important COSP symptoms and impacts had been identified.

Cognitive Debriefing

HCP Findings

Overall, HCPs felt the 28-item COP-Q and seven alternative items (v1_0) assessed concepts relevant to the patient experience of COSP. Six items of the visual tasking module (VTM) were considered to be less relevant to COSP by two of the three HCPs: item 1 (‘reading/typing text messages’); item 2 (‘looking in the mirror to shave/put on make-up’); item 4 (‘reading labels/household bills’); item 8 (‘household chores’); item 10 (‘watching events at a distance’); and item 12 (‘driving during the day’). All HCPs preferred the NRS (severity) and verbal rating scale (VRS) (frequency) to the alternative visual analogue scale (VAS) for assessing daily eye pain. Further, all HCPs who were asked suggested retaining both versions of the HRQoL module assessing frequency and severity, respectively. No major concerns were expressed regarding item wording.

Based on the HCP interviews and feedback from the expert clinical advisors, no modifications were made to the COP-Q (v1_0). However, an additional module assessing current eye pain (on a NRS and alternative VAS) was added following early FDA feedback.

Round 1 Patient Findings

In round one, ten patients completed and debriefed the 29-item COP-Q and eight alternative items (v2_0). An overview of the round one findings is provided in EMS file 3. Most core (n = 24/29) and alternative (n = 7/8) items were understood by ≥ 70.0% of patients asked; some patients did not clearly demonstrate an understanding of the instruction ‘at its worst’ for items in the symptom module. All concepts assessed by the items were considered to be relevant by ≥ 50.0% of patients. With the exception of item 10 (‘watch events at a distance’) of the VTM, ≥ 90.0% of patients who indicated a concept was relevant to their experience also reported experiencing the concept within the specified recall period. The response scales were generally understood and considered to be appropriate across modules. However, for the VTM, patients often described impacts in terms of how much their ability to do each activity was affected, rather than how difficult the activity was for them to do. PGI-S and PGI-C items were understood without difficulty by most of the patients asked. Further, WPAI+CIQ items were considered to be relevant to most patients who debriefed the instrument (ESM file 1).

Following round one, modifications were made to the COP-Q to simplify item wording of the daily eye pain and symptom modules, with the aim to encourage patients to focus on rating each symptom at the time when it was ‘at its worst’. Instructions were also added to the symptom module to further emphasize a focus on symptoms at their worst. The instructions, response options, and item wording of the VTM were also revised to improve comprehension and relevance of the items in COSP populations. Specifically, the VTM was updated to focus on how much of the time eye pain and related problems affected patients’ ability to do vision-dependent activities. This resulted in COP-Q (v3_0), which was submitted to the FDA for feedback on the suitability of the instrument for use in COSP clinical trials.

Modifications Based on FDA Feedback

Based on FDA feedback, the alternative current and daily eye pain modules were removed due to lack of accuracy of a VAS for the comparison of scores over time in the context of a clinical trial. Further, the alternative HRQoL module was removed because an assessment of the frequency of HRQoL concepts was deemed more suitable. To avoid assessment of vision problems unrelated to COSP, two items (item 2: ‘read/type a text message’; item 4: ‘read labels/household bills’) were removed from the VTM and four items (item 3: ‘read books, newspapers, and magazines’; item 5: ‘read on a screen’; item 6: ‘watch TV’; and item 7: ‘work on a computer’) were modified to ask patients to think about doing the activity for a longer duration (i.e., > 1 h). Items in the VTM were also reordered to prioritize concepts most relevant to patients. The recall periods for the symptom (‘past 7 days’) and daily eye pain severity (‘past 24 h’) modules were reduced to ‘the past 4 h,’ and alternative visual tasking (‘past 4 h’) and symptom (‘past 24 h’) modules were developed to explore appropriateness of shorter recall periods to aid recall accuracy. Minor modifications were made to item wording to ensure consistency and aid comprehension across modules. This resulted in COP-Q (v4_0) for testing in round two. Further, additional PGI-S and PGI-C items were developed to correspond with the COP-Q modules.

Round 2 Patient Findings

In round two, 14 patients completed and debriefed the 27-item COP-Q and 13 alternative items (v4_0). An overview of the round two findings is provided in ESM file 3. All core (n = 27) and alternative (n = 13) items were understood by ≥ 70.0% of patients, and all concepts assessed were relevant to ≥ 50.0% of patients asked. Of those patients who indicated a concept was relevant to their experience, ≥ 70.0% reported experiencing most concepts (n = 24/32, 75.0%) within the specified recall period. For the alternative VTM, unsurprisingly many patients reported that they had not performed the activities within the 4-h recall period. The response scales were generally well understood and considered to be appropriate across each module. PGI-S and PGI-C items were understood by most patients asked without difficulty. Further, WPAI+CIQ items were considered to be relevant to most patients who debriefed the instrument (ESM file 1).

Following round two, the alternative current eye pain module (‘right now’) was removed as assessment within the ‘past 4 h’ was judged to provide a better representation of patients’ current eye pain. The alternative VTM was also removed as it was judged that a 4-h recall period was too short for the functioning concepts being assessed. Further, item 11 (‘locate items while shopping’) was removed from the VTM due to low conceptual relevance, and item 7 (‘work on a computer’) was removed due to conceptual overlap with item 2 (‘read on a screen’). Item 8 (‘eye grittiness’) of the symptom module was also removed due to overlap/redundancy with item 6 (‘feeling like there is something in your eye’). A summary of the content for each version of the COP-Q is provided in ESM file 4.

Discussion

The overall objective of this study was to explore the patient experience of COSP and develop/evaluate content validity of a newly developed PRO instrument (the ‘COP-Q’) and associated PGI items that would be fit-for-purpose for use in COSP trials. A further objective was to assess relevance of the WPAI+CIQ for use in COSP populations.

Concept Elicitation

The symptoms and impacts reported in this study were broadly consistent with those identified in the scientific literature [5,6,7, 11, 13]. However, this study provides more in-depth, qualitative understanding of the patient experience from the perspective of patients themselves than was previously available [6, 12]. Notably, although most symptoms were viewed as distinct concepts, several patients noted similarity between various symptoms (e.g., eye grittiness/foreign body sensation, and burning sensation/eye irritation), suggesting that some may simply be different descriptors being used to describe the same ocular sensations. Patients also described that many of the symptoms they experienced were considered different aspects of pain. The use of multiple descriptors not only highlights the subjective and multifaceted nature of pain but has ensured that all aspects of pain, as it relates to the patient experience of COSP, have been fully explored. Further, severity of COSP symptoms were reported to fluctuate day-to-day, with patients describing the greatest impact on their ability to do activities when pain and related symptoms are most severe. This highlights the importance of considering variability in symptom severity and timing of assessments when assessing the impact of COSP-related symptoms on patients’ vision-dependent activities.

Cognitive Debriefing

The current study provides evidence to support content validity of the COP-Q and PGI-S/PGI-C items. Most patients understood the COP-Q instructions, item wording, and response options as intended and indicated that the concepts assessed by the COP-Q were relevant to their experience (both generally and within the specified recall periods). The relevance of concepts was also confirmed by the HCPs. Findings also support the suitability of the WPAI+CIQ in COSP clinical trials (ESM file 1).

Following round one patient interviews, findings informed modifications to the COP-Q, including refocusing the VTM instructions, item wording, and response options to better align with how patients described the effect of eye pain and related symptoms on their ability to do vision-dependent activities, and simplifying item wording of the daily eye pain and symptom modules to emphasis focus on symptoms at their worst. Several modifications were also made following FDA feedback. Notably, alternative VAS response scales for assessing eye pain severity were removed due to concerns with data accuracy in a clinical trial setting; the alternative HRQoL module was removed as impact frequency was deemed more appropriate to assess than severity; and items assessing concepts that could be due to other vision problems (e.g., presbyopia) were either removed or modified to enhance relevance to COSP. On the advice of the FDA, alternative recall periods were also developed for modules intended to support primary or secondary endpoints (i.e., eye pain severity, visual tasking, and symptom modules) to assess the appropriateness of shorter recall periods to aid recall accuracy.

Findings from round two patient interviews indicated that all core and alternative items (n = 38/38) were understood by ≥ 70.0% of patients. Importantly, modifications to the symptom module appeared to improve patients’ comprehension as almost all patients (n = 11/14) responded thinking about each symptom concept when ‘at its worst.’ Modifications to the VTM also increased patients’ ability to select a response that most accurately reflected their experience. All concepts assessed by the items were also relevant to ≥ 50.0% of patients, and most were relevant within the specified recall period. However, across both rounds of interviews, the relevance of item 11 (‘locate items while shopping’) of the VTM was consistently low and, therefore, the item was removed from the COP-Q. Similarly, findings from the round two interviews indicated that the 4-h recall period of the alternative VTM was too short for assessing functioning, as many had not done the activities within the 4-h recall period; therefore, it was determined that a 7-day recall period was more appropriate and the alternative module was removed. Two items were also removed due to conceptual overlap with other items: namely, symptom module item 8 (‘eye grittiness’) due to overlap with item 6 (‘feeling like there is something in your eye’), and VTM item 7 (‘work on a computer’), due to overlap with item 2 (‘read on a screen’). This led to the 22-item COP-Q being taken forward for psychometric validation (ESM file 5).

A key focus of this research was to determine the most appropriate recall periods for assessing symptoms and functional impacts within a COSP population. While patients generally found it easier to recall over a shorter timeframe (e.g., ‘the past 4 h’), the findings suggested that a recall period of the past 7 days is more appropriate for assessment of visual functioning concepts, to avoid high levels of missing data. Therefore, recall periods employed in the COP-Q have been developed to capture fluctuation in symptom experience while accounting for the chronic nature of the condition, in line with regulatory guidance and also with consideration given to the frequency that patients perform day-to-day activities [15, 16].

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this research was the use of comprehensive qualitative methods to explore the patient experience of COSP. Qualitative interviews were supplemented with real-time data collection via a DDAT, affording in-depth insight into patients’ experiences of COSP as they happened and providing greater ecological validity and confidence in the qualitative interview findings [30, 31]. The multi-stakeholder approach employed ensured a robust PRO development process, with the inclusion of: (1) a large sample of patients from the USA who provided evidence for the instrument’s content; (2) HCPs from the USA, Canada, and France who provided feedback on the suitability of the instrument for use in COSP populations; and (3) clinical guidance throughout from a steering committee of expert clinicians from the USA. Multiple rounds of interviews also allowed for modifications to be incorporated and tested. Importantly, regulatory feedback from the FDA was implemented between interview rounds, further strengthening the instrument development process. The interview and DDAT sample included patients with a wide range of underlying conditions and good representation of other key demographic and clinical characteristics. Notably, a range of educational levels were included, which is important when assessing the consistency of understanding of the COP-Q across the COSP population. Although there was less representation of patients with mild COSP, focus was given to capturing the most important and bothersome aspects for patients with moderate-severe COSP most in need of adequate treatments.

However, findings should be interpreted considering the study limitations. As no universally accepted diagnostic criteria currently exist for COSP, patients were recruited to this study based on eligibility criteria defined on the advice of the expert clinicians. Consequently, recruiting clinicians may have been less familiar with the criteria used compared with more well-defined conditions, which could have led to variation in interpretation. Further, it was not always possible to explore novel concepts reported during the DDAT in-depth. However, the DDAT findings provide greater insight into the pervasiveness and variability of COSP symptoms and associated impacts than would have been possible with interviews alone.

Conclusions

The study findings make an important contribution to the literature by providing valuable qualitative insights into the patient experience of COSP from a multi-stakeholder perspective. The findings supported the development of a conceptual model providing a comprehensive depiction of the experience of COSP and provided evidence of content validity for the COP-Q as an assessment of symptoms, vision-function impairments, and distal HRQoL in COSP, in accordance with regulatory guidance. Ongoing research to evaluate the psychometric validity of the COP-Q will support future use of the instrument in clinical trial efficacy endpoints.

Data Availability

The dataset generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Galor A, Hamrah P, Haque S, Attal N, Labetoulle M. Understanding chronic ocular surface pain: an unmet need for targeted drug therapy. Ocul Surf. 2022;26:148–56.

Jacobs DS. Diagnosis and treatment of ocular pain: the ophthalmologist’s perspective. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2017;5(4):271–5.

Mehra D, Cohen NK, Galor A. Ocular surface pain: a narrativereview. Ophthalmol Therapy. 2020;9(3):1–21.

Dermer H, Lent-Schochet D, Theotoka D, et al. A review of management strategies for nociceptive and neuropathic ocular surface pain. Drugs. 2020;80(6):547–71.

Kalangara JP, Galor A, Levitt RC, Felix ER, Alegret R, Sarantopoulos CD. Burning eye syndrome: do neuropathic pain mechanisms underlie chronic dry eye? Pain Med. 2016;17(4):746–55.

Cook N, Mullins A, Gautam R, et al. Evaluating patient experiences in dry eye disease through social media listening research. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(3):407–20.

Andersen HH, Yosipovitch G, Galor A. Neuropathic symptoms of the ocular surface: dryness, pain, and itch. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;17(5):373–81.

Labetoulle M, Rolando M, Baudouin C, van Setten G. Patients’ perception of DED and its relation with time to diagnosis and quality of life: an international and multilingual survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(8):1100–5.

Saldanha IJ, Petris R, Han G, Dickersin K, Akpek EK. Research questions and outcomes prioritized by patients with dry eye. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(10):1170–9.

Galor A, Moein HR, Lee C, et al. Neuropathic pain and dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2018;16(1):31–44.

Karpecki P. When the pain won’t go away: early diagnosis is key to helping patients overcome neuropathic pain associated with dry eye disease. Rev Optom. 2019;153(11):29–31.

Uchino M, Schaumberg DA. Dry eye disease: impact on quality of life and vision. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2013;1(2):51–7.

Miljanović B, Dana R, Sullivan DA, Schaumberg DA. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(3):409–15.

Siedlecki AN, Smith SD, Siedlecki AR, Hayek SM, Sayegh RR. Ocular pain response to treatment in dry eye patients. Ocul Surf. 2020;18(2):305–11.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009. https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download. Accessed Feb 2023.

US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: methods to identify what is important to patients. Guidance for industry, administrative staff, and other stakeholders (Guidance 2). 2022. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-focused-drug-development-methods-identify-what-important-patients. Accessed Feb 2023.

Qazi Y, Hurwitz S, Khan S, Jurkunas UV, Dana R, Hamrah P. Validity and reliability of a novel ocular pain assessment survey (OPAS) in quantifying and monitoring corneal and ocular surface pain. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(7):1458–68.

Özcura F, Aydin S, Helvaci MR. Ocular surface disease index for the diagnosis of dry eye syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2007;15(5):389–93.

McAlinden C, Pesudovs K, Moore JE. The development of an instrument to measure quality of vision: the quality of vision (QoV) questionnaire. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(11):5537–45.

Abetz L, Rajagopalan K, Mertzanis P, et al. Development and validation of the impact of dry eye on everyday life (IDEEL) questionnaire, a patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measure for the assessment of the burden of dry eye on patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9(1):111.

Bouhassira D, Attal N, Fermanian J, et al. Development and validation of the neuropathic pain symptom inventory. Pain. 2004;108(3):248–57.

Schaumberg DA, Gulati A, Mathers WD, et al. Development and validation of a short global dry eye symptom index. Ocul Surf. 2007;5(1):50–7.

Sakane Y, Yamaguchi M, Yokoi N, et al. Development and validation of the dry eye-related quality-of-life score questionnaire. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(10):1331–8.

Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, Spritzer K, Berry S, Hays RD. Development of the 25-item national eye institute visual function questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(7):1050–8.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–65.

Turner-Bowker DM, Lamoureux RE, Stokes J, et al. Informing a priori sample size estimation in qualitative concept elicitation interview studies for clinical outcome assessment instrument development. Value Health. 2018;21(7):839–42.

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

Atlas.ti software version 8 [computer program]. 2013. Berlin: Atlas.ti

Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229–45.

Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1–32.

Rudell K, Tatlock S, Panter C, Arbuckle R, Symonds T. Assessing the methodological value of digital real-time collection of qualitative content in supporting in-depth qualitative interviews exploring the symptoms and impacts of gout on health-related quality of life. Value Health. 2014;17(7):A572.

Zhang W, Bansback N, Boonen A, Young A, Singh A, Anis AH. Validity of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire–general health version in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(5):R177.

Wahlqvist P, Guyatt GH, Armstrong D, et al. The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire for patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (WPAI-GERD): responsiveness to change and English language validation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(5):385–96.

Phang JK, Kwan YH, Fong W, et al. Validity and reliability of Work Productivity and Activity Impairment among patients with axial spondyloarthritis in Singapore. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020;23(4):520–5.

Reilly Associates. WPAI general information. 2019. http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_General.html. Accessed Feb 2023.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Chelsea Finbow contributed to the study design, study conduct, and qualitative analysis, Alyson Young assisted with manuscript preparation, and Garima Sharma contributed to the conduct of the targeted qualitative literature and blog review. Alyson Young is an employee of Adelphi Values. Chelsea Finbow was an employee of Adelphi Values at the time the work was performed. Garima Sharma is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG. The assistance was funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

Funding

Adelphi Values were commissioned by Novartis Pharma AG to conduct this research, and the sponsor contributed to the study design, data collection, and preparation of the manuscript for publication. Novartis Pharma AG also funded the publication of this research and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors from Adelphi Values (Amy Findley, Nicola Hodson, Sarah Bentley, and Rob Arbuckle) contributed to the study design, data collection, interpretation of data, and preparation of the manuscript for publication. All sponsor authors (Brigitte J. Sloesen, Paul O’Brien, Michela Montecchi-Palmer, and Christel Naujoks) contributed to defining the scope of the research, including study design and interpretation of study results in the manuscript. The clinical expert authors (Paul Karpecki and Pedram Hamrah) contributed to the interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Paul Karpecki is an employee of Kentucky Eye Institute and the University of Pikeville Kentucky College of Optometry, Kentucky, USA. Brigitte J. Sloesen and Christel Naujoks are employees of Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Paul O’Brien was an employee of Novartis Ireland Ltd. at the time of performing the research and preparing the manuscript, and is currently an employee of ViiV Healthcare. Michela Montecchi-Palmer was an employee of Novartis Pharma AG at the time of performing the research and preparing the manuscript, and is currently an employee of Alcon. Nicola Hodson, Sarah Bentley, and Rob Arbuckle are employees of Adelphi Values, a health outcomes agency commissioned by Novartis Pharma AG to conduct this research. Amy Findley was an employee of Adelphi Values at the time the work was performed, and is now an employee of Novo Nordisk. Pedram Hamrah is an employee of the Department of Ophthalmology, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, USA. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval and oversight were provided by Western Copernicus Group Independent Review Board (WCG IRB, reference: 1284816), a centralized IRB, to conduct qualitative interviews and daily diary app task activity in the USA. All participants provided oral and written informed consent prior to the conduct of any research activities. The research was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments.

Additional information

Prior Presentation: The research presented in this manuscript was previously presented at International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Europe on 2 Dec 2021 in Copenhagen, Denmark [Sloesen B, Walsh O, O'Brien P, Bentley S, Hodson N, Finbow C, Findley A, Montecchi-Palmer M, Haque S. POSC371 Qualitative research exploring the patient experience of symptoms and health-related quality of life impacts in chronic ocular surface pain. Value in Health. 2022:25(1):S245].

Amy Findley, Paul O’Brien and Michela Montecchi-Palmer’s affiliations have changed since the time of the study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karpecki, P.M., Findley, A., Sloesen, B.J. et al. Qualitative Research to Understand the Patient Experience and Evaluate Content Validity of the Chronic Ocular Pain Questionnaire (COP-Q). Ophthalmol Ther 13, 615–633 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-023-00860-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-023-00860-4