Abstract

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Infectious Diseases (COID) periodically publishes recommendations for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunoprophylaxis (IP) use in pediatric patients considered to be at highest risk for severe RSV infection. In 2014, for the first time, the AAP COID stopped recommending the use of RSV IP for otherwise healthy infants born at 29 weeks’ gestational age (wGA) or later, stating that RSV hospitalization (RSVH) rates in this population are similar to those of term infants. Subsequently, epidemiological studies in the US at national and regional levels provided evidence of the impact of the policy change in 29–34 wGA infants. The results of these studies demonstrated a significant decrease in IP use after 2014 that was associated with an increased rate of RSVH in 29–34 wGA infants and an increase in morbidities. RSVH-related morbidities included pediatric intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, an increased need for mechanical ventilation, and an increase in the length of stay. After the change in recommendations, the costs of RSVH also rose among 29–34 wGA infants. The severity of the illness and expenses associated with RSVH were generally higher among 29–34 wGA infants of younger chronologic age compared with older preterm infants. Overall, these studies underscore that 29–34 wGA infants continue to be a high-risk pediatric population that could benefit from the protection provided by RSV IP. On the basis of these data, in 2018, the National Perinatal Association developed guidelines that recommended RSV IP for all ≤ 32 wGA infants and 32–35 wGA infants with additional risk factors. Re-evaluation of the AAP COID policy is warranted in light of these observations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the US, risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in 29–34 weeks’ gestational age (wGA) infants increased following the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) 2014 policy change regarding RSV immunoprophylaxis (IP) with palivizumab. |

RSVH-related morbidities, including the need for intensive care unit admission and mechanical ventilation, length of stay, and costs associated with RSVH, also increased among 29–34 wGA infants after the 2014 policy change. |

Both the severity parameters and cost of RSVH were generally higher among 29–34 wGA infants of younger chronologic age compared with older preterm infants, indicating a need for careful re-evaluation of the AAP policy for RSV IP use. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13326560.

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection continues to be a substantial socioeconomic burden among specific high-risk infants and children [1, 2]. Treatment of RSV disease is primarily supportive, and efforts to develop a safe and effective vaccine have been unsuccessful to date [2]. Palivizumab is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved immunoprophylaxis (IP) available for the prevention of severe RSV infection among high-risk pediatric groups, including infants born prematurely (≤ 35 weeks’ gestational age [wGA]), children with chronic lung disease, and children with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease [2, 3]. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Infectious Diseases (COID) has narrowed its recommendations for RSV IP use in the high-risk pediatric population since the approval of palivizumab in 1998 [4]. The 2012 AAP COID stated that all < 32 wGA infants and 32 to < 35 wGA infants with at least one additional risk factor (childcare attendance or living with one or more siblings aged < 5 years) would benefit from RSV IP use. Additional preventive measures, especially for high-risk infants, include avoidance of tobacco smoke exposure and crowded places, good hand hygiene, and breastfeeding [5]. In 2014, the AAP stopped recommending RSV IP for otherwise healthy infants born at 29 wGA or later and claimed that there were similar rates of RSV hospitalization (RSVH) in this population and infants born at term [6, 7]. Subsequent studies conducted after the 2014 policy demonstrated a significant decline in RSV IP use after 2014 and an increase in the risk of RSVH in 29–34 wGA infants compared with term infants [4, 8,9,10]. Since 2014, national and regional studies have also assessed the impact of the policy change on RSV disease severity and costs in 29–34 wGA infants.

In 2015, McLaurin et al. modeled the potential impact of the 2014 AAP policy on RSV disease outcomes in 29–34 wGA infants (N = 123,687) with 2012 natality data. Using an eight-step model, the authors predicted that the 2014 AAP policy change could increase RSV disease burden, resulting in an additional 1162 intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and use of mechanical ventilation (MV) in an additional 584 infants and increasing hospital length of stay (LOS) by 24,440 days compared with the 2012 policy [11]. This article will discuss experiential evidence in the US that has analyzed the severity and costs associated with RSVH among 29–34 wGA infants after the 2014 AAP policy change (Table 1). Although the AAP policy may be adapted by countries around the world, the current article is aimed at discussing the implications of the policy change in the US only. The effects of the policy change in the US may be unique compared with the rest of the world, where scope of practice and clinical experience may differ. Indeed, in many resource-poor countries, there is significant morbidity and increased mortality from RSV [12, 13]. Furthermore, generalization is difficult because of differences in the pricing of RSV IP, insurance coverage, and medical practice between countries. Therefore, the discussion of the guidelines and policies followed in countries outside the US and their implications are beyond the scope of this review. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Characterization of RSV Disease Severity and Hospital Charges in 29–35 wGA Infants Who Did Not Receive RSV IP

In the two-season SENTINEL1 study, Anderson et al. characterized the severity of RSVH in high-risk 29–35 wGA infants who did not receive RSV IP. This large, prospective and retrospective, observational study included data from 46 US sites, the majority of which were children’s hospitals and/or academic institutions, for the 2014–2015 and 2015–2016 RSV seasons [1, 14]. A total of 1378 infants with community-acquired RSV disease were analyzed. The proportion of 29–35 wGA infants aged < 6 months requiring hospitalization, ICU admission, and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) was 78%, 84%, and 91%, respectively. Among infants born at 29–35 wGA with RSVH, 45% (n = 610) were admitted to the ICU (Fig. 1a) and 19% (n = 265) required IMV (Fig. 1b). LOS in the hospital was higher among infants of earlier gestational age and younger chronologic age. Mean hospital LOS among infants born at 29–32 wGA, 33–34 wGA, and 35 wGA during the two combined seasons was 10, 9, and 7 days, respectively. The study also demonstrated that the rates of ICU admissions and IMV use were higher among infants of earlier gestational age and younger chronologic age. In addition, hospital charges increased as gestational age and chronologic age decreased, and the mean hospital charges were highest for 29–32 wGA infants aged < 3 months ($122,301). Estimates of mean hospital charges stratified on the basis of gestational age and chronologic age for 29–35 wGA infants in the combined 2014–2016 seasons are shown in Fig. 1c [1]. SENTINEL1 provided a detailed characterization of the substantial morbidity and costs associated with RSVH in high-risk populations not receiving RSV IP that lie outside of the AAP policy [1].

Republished with permission of Am J Perinatol, from Anderson EJ, et al., 37, 4 © 2019; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Severity (a, b) and hospital charges (c) associated with RSVH among 29–35 wGA infants who did not receive RSV IP [1]. CA chronologic age, ICU intensive care unit, IMV invasive mechanical ventilation, IP immunoprophylaxis, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, RSVH respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization, USD US dollars, wGA weeks’ gestational age.

Impact of 2014 AAP Policy Change on RSV Disease Severity in 29–34 wGA Infants

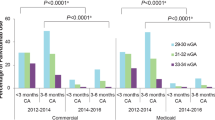

Evidence from large databases and regional studies showed the impact of the AAP 2014 policy change among infants aged < 6 months. In a recent retrospective observational study, Krilov et al. used medical and pharmacy claims from the Optum Research Database to compare the severity of RSVH in commercially insured 29–34 wGA infants (n = 12,558) and term infants (n = 323,216) during 2011–2014 and 2014–2017 RSV seasons. Following the 2014 AAP policy change, there was a significant decrease in RSV IP use in 29–34 wGA infants of all gestational age groups (P < 0.001) that was associated with a significant increase in RSVH risk in 29–34 wGA infants vs. term infants (P = 0.011). Hospitalization rates for term infants remained constant during the RSV seasons studied. Additionally, the mean LOS for RSVH increased significantly in 2014–2017 (7.8 days) vs. 2011–2014 (4.7 days; P = 0.028). Similarly, the proportion of ICU admissions was higher in 2014–2017 vs. 2011–2014 for 29–34 wGA infants (48.8% vs. 26.6%, respectively; P = 0.006) (Fig. 2a). However, there was no significant change in mean LOS or ICU admissions before vs. after 2014 among term infants. The use of MV was also higher in 2014–2017 vs. 2011–2014 in 29–34 wGA infants (15.9% vs. 6.3%, respectively; P = 0.073); however, this was not statistically significant (Fig. 2b). In general, RSV disease was more severe among 29–34 wGA infants of younger chronologic age (< 3 months) [4].

Republished with permission of Am J Perinatol, from Krilov LR, et al., 37, 2 © 2019; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

RSV disease severity increased after 2014 in 29–34 wGA infants who did not receive RSV IP [4]. ICU intensive care unit, IP immunoprophylaxis, MV mechanical ventilation, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, wGA weeks’ gestational age.

A few regional studies have assessed the impact of the policy change on the severity of illness parameters of RSVH since 2014. In a single-center study at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Rajah et al. analyzed 1063 cases of RSVH and reported a significant decrease in RSV IP use after 2014 (P < 0.001) and an associated increase in RSVH in 29–34 wGA infants aged < 6 months (P = 0.01). Compared with the 2013–2014 RSV season, the proportion of ICU admissions (30.0% [n = 3] vs. 68.4% [n = 13]; P = 0.04), use of MV (10.0% [n = 1] vs. 52.6% [n = 10]; P = 0.04), and LOS of RSVH (1.8 days vs. 8.8 days; P = 0.04) increased significantly in 2014–2015 among 29–34 wGA infants aged < 3 months [10].

In another recent study, Zembles et al. assessed RSVH outcomes from 2012 to 2017 in 29–34 wGA infants aged < 1 year (n = 91). Although the authors did not observe a significant year-to-year increase in RSVH during the three subsequent RSV seasons after 2014, the combined proportion of RSVH in 2014–2017 was significantly higher (17.2%) than it had been in 2012–2014 (9.2%; P = 0.0047; unpublished data). Comparative analysis of RSV disease severity with the small number of RSVH that occurred in 2014–2017 (n = 61) and 2012–2014 (n = 30) did not reveal any significant difference in the proportion of ICU admissions or MV use. However, the median LOS of RSVH increased by 2 days in 2014–2017 vs. 2012–2014 (7.86 days vs. 5.86 days, respectively; P = 0.02) [15].

Overall, after the AAP stopped recommending RSV IP use among 29–34 wGA infants in 2014, these epidemiological studies indicate that the severity of RSV illness increased for this patient population [4, 10].

Impact of AAP Policy Change on RSV Hospitalization Costs After 2014 in 29–34 wGA Infants

RSVH occurring in high-risk infants often requires ICU admission and MV, adding to the economic burden associated with RSV disease [1]. Several studies have assessed the difference in hospital expenditures associated with RSVH in 29–34 wGA infants before and after the policy change. Goldstein et al. reported that 29–34 wGA infants incurred higher average RSVH costs (costs adjusted to 2016 US dollars [USD]) than term infants in all RSV seasons between 2012 and 2016. In general, RSVH costs increased in 2014–2016 vs. 2012–2014, and the highest expenses were common among 29–34 wGA infants compared with term infants. In 2014–2016, mean RSVH costs for 29–34 wGA infants aged < 3 months were more than double those of term infants (commercially insured, $41,104 vs. $17,597; Medicaid-insured, $24,049 vs. $10,897) [8].

Krilov et al. reported that mean RSVH costs (costs adjusted to 2015 USD) for 29–34 wGA infants aged < 6 months increased from $17,157 in 2011–2014 to $41,363 in 2014–2017, although this increase was not significant (P = 0.089). However, increases in RSVH costs were minimal among term infants ($14,674 in 2011–2014 to $16,337 in 2014–2017; P = 0.148; Fig. 3) [4]. Both of these studies demonstrated that hospital costs were generally higher for infants of younger chronologic age (aged < 3 months), corroborating the findings of SENTINEL1 and confirming that RSV illness severity was as much of a concern as it had been at the time that SENTINEL1 was reported [4, 8].

Republished with permission of Am J Perinatol, from Krilov LR, et al., 37, 2 © 2019; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Costs associated with RSVH were higher for 29–34 wGA infants than for term infants after the 2014 policy change [4]. RSV respiratory syncytial virus, RSVH respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization, USD US dollars, wGA weeks’ gestational age.

Rajah et al. observed that hospital expenditures for 29–34 wGA infants requiring RSVH increased after 2014. Median hospital charges associated with RSVH were higher in 2014–2015 vs. 2013–2014 for all analyzed infants ($31,339 vs. $19,947; P = 0.02) [10]. Collectively, these studies underscore the high economic burden associated with RSVH in 29–34 wGA infants that further increased after the policy change.

Conclusions

RSV disease continues to be a substantial social and economic concern with high morbidity and costs associated with RSVH in high-risk infants, especially 29–34 wGA infants [1]. As correctly predicted by McLaurin et al., national and regional cohorts have shown that RSVH outcomes such as ICU admission, need for MV, and LOS have increased among 29–34 wGA infants in the RSV seasons following the 2014 AAP policy change [4, 8, 10, 11]. In 2018, the National Perinatal Association (NPA) published clinical practice guidelines recommending RSV IP use in 29–35 wGA infants based on the evidence demonstrating an increase in RSVH and morbidity among these high-risk patients [16]. Nevertheless, in 2019, the AAP COID reaffirmed the 2014 policy change for RSV IP [17]. We believe that the new evidence warrants a re-evaluation of the AAP COID policy.

References

Anderson EJ, DeVincenzo JP, Simões EAF, et al. SENTINEL1: Two-season study of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among U.S. infants born at 29 to 35 weeks’ gestational age not receiving immunoprophylaxis. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37(4):421–9.

Simões EAF, Bont L, Manzoni P, et al. Past, present and future approaches to the prevention and treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. Infect Dis Ther. 2018;7(1):87–120.

SYNAGIS [package insert]. Gaithersburg, MD: MedImmune, LLC; 2017.

Krilov LR, Fergie J, Goldstein M, Brannman L. Impact of the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics immunoprophylaxis policy on the rate, severity, and cost of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37(2):174–83.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Respiratory syncytial virus. 2012. In: Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics Bronchiolitis Guidelines Committee. Updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):415–20.

Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1474–502.

Goldstein M, Krilov LR, Fergie J, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among U.S. preterm infants compared with term infants before and after the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics guidance on immunoprophylaxis: 2012–2016. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35(14):1433–42.

Kong AM, Krilov LR, Fergie J, et al. The 2014–2015 national impact of the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics guidance for respiratory syncytial virus immunoprophylaxis on preterm infants born in the United States. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35(2):192–200.

Rajah B, Sánchez PJ, Garcia-Maurino C, Leber A, Ramilo O, Mejias A. Impact of the updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis against respiratory syncytial virus infection: a single center experience. J Pediatrics. 2017;181(183–8):e1.

McLaurin KK, Chatterjee A, Makari D. Modeling the potential impact of the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis guidance on preterm infant RSV outcomes. Infect Dis Ther. 2015;4(4):503–11.

Shi T, McAllister DA, O’Brien KL, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet. 2017;390(10098):946–58.

Aranda SS, Polack FP. Prevention of pediatric respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract illness: perspectives for the next decade. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1006.

Anderson EJ, Krilov LR, DeVincenzo JP, et al. SENTINEL1: an observational study of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among U.S. infants born at 29 to 35 weeks’ gestational age not receiving immunoprophylaxis. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34(1):51–61.

Zembles TN, Bushee GM, Willoughby RE. Impact of American Academy of Pediatrics palivizumab guidance for children >/=29 and <35 weeks of gestational age. J Pediatrics. 2019;209:125–9.

Goldstein M, Phillips R, DeVincenzo JP, et al. National Perinatal Association 2018 Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Prevention Clinical Practice Guideline: an evidence-based interdisciplinary collaboration. Neonatol Today. 2017;12(10):1–14.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics Bronchiolitis Guidelines Committee. Updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):415–420. Reaffirmed February 2019.

Acknowledgements

This supplement has been sponsored by Sobi, Inc. Robert C. Welliver served as the Guest Editor for this supplement and has the following disclosures:

He has received funding from Novavax for preclinical work on their RSV vaccine in a maternal immunization study, funding from AZ for evaluation of nirsevimab, past funding from AstraZeneca for various RSV antibody studies, and from MedImmune before that.

He has also received funding from Regeneron in the past for their RSV monoclonal antibody study. Finally, he is receiving NIAID (1 R41 A147787-01) funding for study of an RSV vaccine.

Funding

This study and the Rapid Service Fees were sponsored by Sobi, Inc.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Writing and editorial support were provided by PRECISIONscientia, Inc., which were in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines and funded by Sobi, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Leonard R. Krilov has received grant and research support for clinical trials from AstraZeneca, Regeneron, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur. LRK has been a consultant to Sobi and Pfizer. Michael L. Forbes has received grant and research support from AstraZeneca/MedImmune and is a member of the AstraZeneca Speakers Bureau. Mitchell Goldstein has received grant and research support from AstraZeneca/MedImmune and is a member of the AstraZeneca Speakers Bureau. Rajan Wadhawan has been a member of an advisory board for AstraZeneca. Dan L. Stewart has been a member of an advisory board for AstraZeneca and is a member of the AstraZeneca and Sobi Speakers Bureaus.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krilov, L.R., Forbes, M.L., Goldstein, M. et al. Severity and Cost of RSV Hospitalization Among US Preterm Infants Following the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Change. Infect Dis Ther 10 (Suppl 1), 27–34 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00389-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00389-0