Abstract

Despite being a leading cause of hospitalization due to lower respiratory tract infections, the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is primarily supportive. Palivizumab is the only licensed immunoprophylaxis (IP) available for preventing severe RSV infection in high-risk populations including ≤ 35 weeks’ gestational age (wGA) infants and children with chronic lung disease of prematurity or congenital heart disease. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has published its IP recommendations since the approval of palivizumab. In 2014, the AAP stopped recommending RSV IP in 29–34 wGA infants without comorbidities and stated that RSV hospitalization (RSVH) risk in otherwise healthy ≥ 29 wGA infants and term infants was similar. Since then, experts in the field have debated the appropriateness of the 2014 policy change, and several real-world evidence studies at the national and regional levels in the US have examined the impact of the AAP policy on 29–34 wGA infants. Overall, these studies showed a significant decline in RSV IP use and a concurrent increase in RSVH risk among 29–34 wGA infants relative to term infants in the seasons after the 2014 policy change. A similar decrease in IP use and increase in RSVH risk was also observed among < 29 wGA infants relative to term infants after the 2014 policy change. This decrease could be an unintended consequence as < 29 wGA infants are an in-policy population recommended to receive RSV IP. According to the National Perinatal Association, strong evidence exists to support the use of RSV IP in all ≤ 32 wGA and 32–35 wGA infants with risk factors such as attending day care, having ≥ 1 school-aged siblings, twin or greater multiple gestation, younger age, and exposure to parental smoking. Until new preventive and treatment options become available, palivizumab can help prevent and mitigate RSV disease burden among high-risk preterm infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Currently, palivizumab is the only respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunoprophylaxis (IP) available for use in specific high-risk pediatric populations, including premature (≤ 35 weeks’ gestational age [wGA]) infants. |

In 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) stopped recommending RSV IP use in otherwise healthy 29–34 wGA infants without comorbidities and stated that RSV hospitalization (RSVH) risk in otherwise healthy ≥ 29 wGA infants and term infants was similar. |

Real-world evidence studies conducted in the US after the 2014 policy change have reported a decrease in RSV IP use that is largely associated with an increase in RSVH risk among 29–34 wGA infants relative to term infants. |

In addition, RSV IP use decreased and RSVH risk increased among in-policy, < 29 wGA infants; this could be an unintended consequence of the 2014 policy change. |

Revisions to the AAP recommendations are needed given the growing evidence demonstrating an increase in RSVH risk among 29–34 wGA infants. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13326350.

Introduction

Pediatric populations at high risk for severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection include infants born prematurely (≤ 35 weeks’ gestational age [wGA]) and children with chronic lung disease of prematurity, congenital heart disease, Down syndrome, immunodeficiency, neuromuscular diseases, and cystic fibrosis [1,2,3]. Preterm infants without comorbidities have an approximately three times greater risk of RSV-related hospitalization (RSVH) compared with term infants [4]. Palivizumab is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapy for the prevention of serious lower respiratory tract infections caused by RSV in high-risk infants [1, 5]. In 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Infectious Diseases (COID) stopped recommending RSV immunoprophylaxis (IP) for preterm infants born at ≥ 29 wGA without comorbidities such as chronic lung disease of prematurity and congenital heart disease [6]. The committee’s rationale for the change was that the risk of RSVH in infants born at ≥ 29 wGA was similar to that observed in term infants [7]. However, the studies used as evidence to support the policy change were widely non-generalizable, regional studies and lacked sufficient power, unlike the well-designed, randomized clinical trials that established the safety and efficacy of palivizumab [8, 9].

Following the 2014 AAP policy change, several real-world evidence studies examined the impact of these updates on RSV IP use and RSVH among infants 29–34 wGA. This article will provide a comprehensive review of RSVH data from the 2011–2017 RSV seasons in the US obtained from single-center, regional, and sizeable national database studies conducted after the 2014 AAP policy change (Table 1). Although the AAP policy may be adapted by countries outside the US, this article is aimed at discussing the implications of the policy change in the US only. There may be significant effects from the use of a policy that is beyond the scope of practice and clinical experience of much of the rest of the world. Indeed, there is significant morbidity and increased mortality from RSV in many resource-poor countries [10, 11]. However, the discussion of the guidelines and policies followed in countries outside the US and their implications are beyond the scope of this review. Please also note that the pricing of RSV IP, insurance coverage, and medical practice vary between countries; thus, generalizing is difficult. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Impact of the 2014 AAP Policy on RSVH in Preterm Infants From Single-Center and Regional Studies

Data from regional studies that assessed the risk of RSVH before and after the 2014 policy change have demonstrated mixed results. In a pooled analysis of data from eight Medicaid plans, Farber reported that RSVH (N = 2031) among 29–32 wGA infants did not change significantly in the three seasons examined (4.65%, 2012–2013; 3.06%, 2013–2014; 5.41%, 2014–2015) [12]. However, the Texas Medicaid plan had not adopted the 2014 AAP policy for the 2014–2015 season, and infants who received inpatient IP were not captured [6, 13, 14]. Additionally, the group receiving IP was younger than those not receiving IP, suggesting the groups may not be comparable [14, 15]. In another retrospective analysis, Grindeland et al. reported that RSV IP use decreased significantly in 2014–2015 compared with 2012–2014 (P < 0.0001) among hospitalized children aged < 2 years in North Dakota. The total number of RSVH during the study period was 194, and no significant change was observed in RSVH rates per 1000 children in the 2012–2014 vs. 2014–2015 seasons (P = 0.622) [16]. However, this study did not specifically examine high-risk preterm infants nor did it have the optimal statistical power to detect significant differences, if present [16, 17].

Rajah et al. conducted a retrospective analysis at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio (N = 2476) and showed that the proportion of RSVH among 29–34 wGA infants aged < 6 months increased significantly in 2014–2015 (7.1%) compared with 2013–2014 (3.5%; P = 0.01) [18]. Similarly, in a single-center analysis of 173 infants, Blake et al. reported that RSV IP prescriptions decreased (P = 0.01) and RSVH increased significantly in 2014–2016 vs. 2012–2014 among infants born at 29 to < 32 wGA (P = 0.04) [19].

In a recent study, Zembles et al. analyzed 91 RSVH in ≥ 29 and < 35 wGA infants aged < 1 year during the 2012–2017 seasons. The authors observed no significant increase in RSVH during the three seasons after the AAP policy change (2014–2017), but the number of RSVH in the first season after the policy change (n = 30, 2014–2015) was greater than in the previous seasons (n = 14, 2012–2013; n = 16, 2013–2014) [20]. Also, an analysis comparing RSVH in the seasons before and after 2014 showed that the proportion of RSVH among ≥ 29 to < 35 wGA infants in 2014–2017 was about two times higher than in 2012–2014 (17.2% vs. 9.7%, respectively; P = 0.0047; unpublished data).

Overall, some regional studies that examined the impact of the 2014 AAP policy either did not fully adopt the policy or did not stratify based on the gestational age group. A limitation of the above-mentioned single-center studies was that they were not controlled for seasonal variations that may have occurred [12, 19]. National studies that analyzed large databases have helped address this limitation by calculating rate ratios to standardize for seasonal variations [21, 22].

Impact of the 2014 AAP Policy on RSVH in Preterm Infants Using Data From National Databases

Although regional studies presented mixed results regarding the impact of the 2014 policy change, extensive national database studies have consistently shown a correlation between the decrease in RSV IP use after 2014 and an increase in the risk of RSVH. Kong et al. conducted a retrospective analysis using the Truven MarketScan® commercial and Medicaid insurance claims databases and compared RSV IP use and RSVH among 29–34 wGA infants in the 2014–2015 season vs. the 2013–2014 season. The proportion of 29–34 wGA infants who received at least one dose of RSV IP significantly decreased by 45–95% in the 2014–2015 vs. 2013–2014 seasons (P < 0.01). Between 2010 and 2015, among 29–34 wGA infants and term infants, a total of 6563 and 13,312 RSVH were identified in the commercial and Medicaid databases, respectively. In 2014–2015, the RSVH rate for commercially insured 29–34 wGA infants aged < 3 months was 2.65 (P = 0.0184) times higher than in 2013–2014; for Medicaid-insured infants of the same age group, the RSVH rate was 1.41 (P = 0.0313) times higher (Fig. 1). In contrast, RSVH rates were similar in 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 among term infants [22].

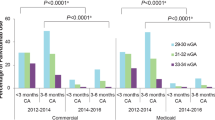

Goldstein et al. extended the examination of the national impact of the AAP policy change among 29–34 wGA infants aged < 6 months in the 2014–2016 vs. 2012–2014 seasons. The analysis included commercially insured infants (29–34 wGA, n = 33,667 and term infants, n = 668,619) and Medicaid-insured infants (29–34 wGA, n = 51,439 and term infants, n = 908,594) [21]. Similar to Kong et al., the proportion of RSV IP use decreased significantly by ≥ 74% for all the preterm age groups analyzed in 2014–2016 compared with 2012–2014 (P < 0.0001, for both commercial and Medicaid databases) [21, 22]. There was no significant change in RSV IP use among term infants before and after 2014. RSVH rate ratios in 29–34 wGA infants relative to term infants were > 1 in all seasons. The risk of RSVH in 29–34 wGA infants vs. term infants was higher in 2014–2016 (range, 2.6–5.6) compared with 2012–2014 (range, 1.6–3.4). The difference-in-difference model that was used to control for gestational age at birth, chronologic age during the RSV season, and sex estimated that the risk of RSVH in 29–34 wGA infants relative to term infants increased significantly in 2014–2016 vs. 2012–2014 (Fig. 2; rate ratio = 2.00 for the commercially insured population; rate ratio = 1.46 for Medicaid population; P < 0.0001 for both) [21].

RSVH risk increased after the 2014 policy change in 29–34 wGA infants relative to term infants (Goldstein et al. [21]). COM commercially insured, MED Medicaid insured, RSVH respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization, wGA weeks’ gestational age. Republished with permission of Am J Perinatol, from Goldstein et al. [21]

In a recent observational cohort study, Krilov et al. analyzed medical and pharmacy claims data from the Optum Research Database in the three seasons before (2011–2014) and after (2014–2017) the policy change. A total of 12,558 preterm infants and 323,216 term infants were included in the analysis. Similar to the Truven studies, the proportion of RSV IP decreased significantly in 29–34 wGA infants (Fig. 3; P < 0.001, for all wGA cohorts). This decrease was associated with a consistently higher RSVH rate ratio among preterm infants relative to term infants in 2014–2017 vs. 2011–2014. The risk of RSVH in 29–34 wGA infants vs. term infants increased from 1.9 in 2011–2014 to 2.9 in 2014–2017. This change represented a 55% increase in the risk of RSVH among 29–34 wGA infants relative to term infants in the 2014–2017 vs. 2011–2014 RSV seasons (P = 0.011) [23].

RSVH risk increased as RSV IP use decreased after the 2014 policy change in 29–34 wGA infants relative to term infants (Krilov et al. [23]). IP immunoprophylaxis, RR rate ratio, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, RSVH respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization; wGA, weeks’ gestational age. Republished with permission of Am J Perinatol, from Krilov et al. [23]

These large studies have some characteristic limitations: (1) RSVH may have been under-coded because of lack of a confirmatory laboratory diagnosis as the AAP does not recommend RSV testing. (2) Underestimation of RSV IP use is a possibility as inpatient IP use was not included in the analysis. (3) Relatively low n values in some gestational age groups may have masked any statistical difference between the seasons [21,22,23].

Overall, large national cohort studies showed that the decline in RSV IP after 2014 was associated with significant increases in RSVH rate and risk among 29 to 34 wGA infants compared with term infants. In addition, the risk of RSVH was highest among infants born at earlier gestational age and of younger chronologic age [21,22,23].

Impact of the AAP Policy on RSVH in Low-Income Populations

Espinosa et al. analyzed RSVH among preterm infants (< 29 wGA, 29–35 wGA, and > 35 wGA) aged < 1 year in a low-income population using Kentucky Medicaid claims data from 2012–2016. The rate of RSVH among 29–35 wGA infants was 328 per 1000 live births in 2014–2016 compared with 172 per 1000 live births in 2012–2013. This increase accounted for a 52% higher incidence rate of RSVH than the expected rate for 2014–2016 (P < 0.001). Of note, the highest increase in RSVH incidence rate was observed among 29–35 wGA infants (86%; P < 0.001), while no significant change was observed among < 29 wGA and > 35 wGA infants in 2014–2016 vs. 2012–2013 [24]. These results indicate that the 2014 policy change may compound the vulnerability of high-risk infants with additional socioeconomic risk factors such as low income.

Unintended Consequences of AAP Policy on RSVH in < 29 WGA Infants

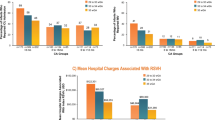

Since 2014, studies have also assessed the potential impact of the AAP policy change on IP use and RSVH among < 29 wGA infants. The AAP considers < 29 wGA infants to be high risk and continues to recommend IP use for this population [1, 6]. Goldstein et al. analyzed commercial and Medicaid claims from the IBM Watson Health MarketScan® database in < 29 wGA infants aged < 12 months in 2014–2016 vs. 2012–2014. Outpatient RSV IP use decreased among < 29 wGA infants for all chronologic age groups in 2014–2016 compared with 2012–2014. The highest decline in IP use was observed in < 29 wGA infants aged < 3 months (46% decline, commercial; 36% decline, Medicaid). This decline was associated with an increase in RSVH rate ratios in < 29 wGA infants relative to term infants in 2014–2016 vs. 2012–2014 for each chronologic age group (both commercially insured and Medicaid-insured infants). For commercially insured < 29 wGA infants aged < 1 year, RSVH rate ratios ranged between 1.13 and 3.59 in 2012–2014 and 4.49 and 5.59 in 2014–2016. Similarly, in Medicaid-insured infants of the same age group, RSVH rate ratios were 1.09–4.88 in 2012–2014 and 3.88–12.48 in 2014–2016. The highest increases in RSVH rate ratios in < 29 wGA infants vs. term infants were observed among infants aged < 3 months [25]. Overall, these results indicate that the AAP 2014 policy change may have resulted in an unintended consequence of decreased RSV IP utilization and increased RSVH among this vulnerable < 29 wGA infant population.

Conclusion

Taken together, data from real-world evidence studies showed that the AAP 2014 policy change resulted in a significant decrease in RSV IP use and an increase in RSVH among both outside-policy (29–34 wGA infants) and in-policy populations (< 29 wGA infants) [18, 19, 21, 22, 25]. Despite the consequential increase in RSVH risk among 29–34 wGA infants, the AAP reaffirmed their 2014 policy change in 2019 [26]. Although the results discussed here are not derived from randomized controlled trials, the studies provide a real-world snapshot of the unfortunate increase in RSV disease morbidity among the affected 29–34 wGA infants. Moreover, conducting randomized controlled trials may be time-consuming and not always possible because of IP that occurs over and under policy intent. Based on the recent evidence demonstrating an increase in RSVH, the National Perinatal Association (NPA) published its 2018 clinical guidelines recommending RSV IP for all ≤ 32 wGA infants and 32–35 wGA infants with risk factors such as day care attendance, presence of school-aged siblings, twin or greater multiple gestation, and younger age. The NPA also highlighted that the guidance and policies should remain consistent with the FDA indication as it provides the most clarification of a clinically significant therapy based on carefully conducted, evidence-based, randomized control trials [5]. As palivizumab is the only FDA-approved intervention to prevent RSV-related complications in high-risk infants, including 29–35 wGA infants, the AAP policy should be revisited in light of recent evidence.

References

SYNAGIS [package insert]. Gaithersburg, MD: MedImmune, LLC; 2017.

Boyce TG, Mellen BG, Mitchel EF Jr, et al. Rates of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection among children in Medicaid. J Pediatrics. 2000;137(6):865–70.

Manzoni P, Figueras-Aloy J, Simões EAF, Checchia PA, Fauroux B, Bont L, et al. Defining the incidence and associated morbidity and mortality of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection among children with chronic diseases. Infect Dis Therapy. 2017;6(3):383–411.

Figueras-Aloy J, Manzoni P, Paes B, Simões EA, Bont L, Checchia PA, et al. Defining the risk and associated morbidity and mortality of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection among preterm infants without chronic lung disease or congenital heart disease. Infect Dis Therapy. 2016;5(4):417–52.

Goldstein M, Phillips R, DeVincenzo JP, Krilov LR, Merritt TA, Yogev R, et al. National Perinatal Association 2018 respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) prevention clinical practice guideline: an evidence-based interdisciplinary collaboration. Neonatol Today. 2017;12(10):1–14.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics Bronchiolitis Guidelines Committee. Updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):415–20.

Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1474–502.

DeVincenzo JP, Krilov LR, Yogev R. Viral bronchiolitis in children. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1791.

Yogev R, Krilov LR, Fergie JE, Weiner LB. Re-evaluating the new Committee on Infectious Diseases recommendations for palivizumab use in premature infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(9):958–60.

Shi T, McAllister DA, O’Brien KL, Simoes EAF, Madhi SA, Gessner BD, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet. 2017;390(10098):946–58.

Aranda SS, Polack FP. Prevention of pediatric respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract illness: perspectives for the next decade. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1006.

Farber HJ. Impact of the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics guidance on respiratory syncytial virus and bronchiolitis hospitalization rates for infants born prematurely. J Pediatrics. 2017;185:250.

Texas Medicaid/CHIP vendor drug program fee-for-service Medicaid Synagis® request form: 2014–15 season. 2019. http://www.maxor.com/forms/MaxorSpecialty/phys-forms/synagis/medicaid_synagis_form%202014-2015%20-%20MxSp%20-%20090314.pdf. Accessed 20 Jun 2019.

Farber HJ, Buckwold FJ, Lachman B, Simpson JS, Buck E, Arun M, et al. Observed effectiveness of palivizumab for 29–36-week gestation infants. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20160627. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0627.

Byington CL, Wilkes J, Korgenski K, Sheng X. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated mortality in hospitalized infants and young children. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e24-31.

Grindeland CJ, Mauriello CT, Leedahl DD, Richter LM, Meyer AC. Association between updated guideline-based palivizumab administration and hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(7):728–32.

Ambrose CS. Statistical power to detect an association between guideline-based palivizumab administration and hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(3):348.

Rajah B, Sánchez PJ, Garcia-Maurino C, Leber A, Ramilo O, Mejias A. Impact of the updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis against respiratory syncytial virus infection: a single center experience. J Pediatrics. 2017;181:183–8.

Blake SM, Tanaka D, Bendz LM, Staebler S, Brandon D. Evaluation of the financial and health burden of infants at risk for respiratory syncytial virus. Adv Neonatal Care. 2017;17(4):292–8.

Zembles TN, Bushee GM, Willoughby RE. Impact of American Academy of Pediatrics palivizumab guidance for children ≥29 and <35 weeks of gestational age. J Pediatrics. 2019;209:125–9.

Goldstein M, Krilov LR, Fergie J, McLaurin KK, Wade SW, Diakun D, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among U.S. preterm infants compared with term infants before and after the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics guidance on immunoprophylaxis: 2012–2016. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35(14):1433–42.

Kong AM, Krilov LR, Fergie J, Goldstein M, Diakun D, Wade SW, et al. The 2014–2015 national impact of the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics guidance for respiratory syncytial virus immunoprophylaxis on preterm infants born in the United States. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35(2):192–200.

Krilov LR, Fergie J, Goldstein M, Rizzo C, Brannman L. Impact of the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics immunoprophylaxis policy on the rate, severity, and cost of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among preterm infants [published online August 20, 2019]. Am J Perinatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1694008.

Espinosa C, Feygin Y, Duncan S, Smith M, Woods C, Myers J. Changes in recommendations for palivizumab administration leads to increase in respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations in low-income children. In: Abstract presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting; May 5–8, 2018; Toronto, ON, Canada. Abstract 1160.01; 2018.

Goldstein M, Krilov LR, Fergie J, Brannman L, Ambrose CS, Wade SW, et al. Impact of the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics guidance on respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization rates for preterm infants <29 weeks gestational age at birth: 2012 to 2016. In: Poster presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting; April 27–30, 2019; Baltimore, MD; poster 525; 2019.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics Bronchiolitis Guidelines Committee. Updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):415–420.

Acknowledgements

This supplement has been sponsored by Sobi, Inc. Robert C. Welliver served as the Guest Editor for this supplement and has the following disclosures: He has received funding from Novavax for preclinical work on their RSV vaccine in a maternal immunization study, funding from AZ for evaluation of nirsevimab, past funding from AstraZeneca for various RSV antibody studies, and from MedImmune before that. He has also received funding from Regeneron in the past for their RSV monoclonal antibody study. Finally, he is receiving NIAID (1 R41 A147787-01) funding for study of an RSV vaccine.

Funding

This study and the Rapid Service Fees were sponsored by Sobi, Inc.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Writing and editorial support were provided by PRECISIONscientia, Inc., which were in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines and funded by Sobi, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Mitchell Goldstein has received grant and research support from AstraZeneca/MedImmune and is a member of the AstraZeneca Speakers Bureau. Jaime Fergie has received grant and research support from AstraZeneca/MedImmune and is a member of the AstraZeneca and Sobi Speakers Bureaus. Leonard R. Krilov has received grant and research support for clinical trials from AstraZeneca, Regeneron, Sanofi Pasteur, and Pfizer. LRK has also been a consultant to Sobi as well as Pfizer.

Compliance with Ethics Guideline

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goldstein, M., Fergie, J. & Krilov, L.R. Impact of the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics Policy on RSV Hospitalization in Preterm Infants in the United States. Infect Dis Ther 10 (Suppl 1), 17–26 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00388-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00388-1