Abstract

Introduction

Real-world treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is complicated by many factors that are controlled for in the rigorous clinical trial setting. The aim of the present study was to assess the efficacy of elbasvir/grazoprevir in a Veterans Affairs population with chronic HCV genotype 1b infection.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of a cohort of patients aged ≥ 18 years with chronic HCV genotype 1b infection and ≥ 1 prescription of elbasvir/grazoprevir between February 1, 2016, and August 31, 2017. The primary analysis was conducted in the per-protocol population, which included all patients who had at least 11 weeks of treatment and had an available assessment for sustained virologic response (SVR) based on virologic data post–follow-up week 4.

Results

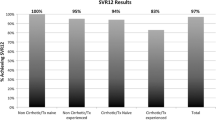

The per-protocol population included 3371 patients. Overall, 97.3% of patients were male, 60.3% were black, and 85.5% were HCV treatment–experienced. Comorbidities in this population included hypertension (74.4%), history of alcohol use (55.7%), and depression (54.8%). In total, 97.5% of patients (3288/3371) achieved SVR. Among patient sub-groups, SVR was achieved by 96.0% (290/302) of those with chronic kidney disease stage 4/5, 97.8% (1527/1561) of those with a history of drug use, and 96.6% (831/860) of those with cirrhosis. No statistically significant differences were observed in the proportions of patients achieving SVR, regardless of age, race, HCV treatment history, viral load level, treatment regimen/duration, history of drug or alcohol use, HIV co-infection, or chronic kidney disease.

Conclusion

Elbasvir/grazoprevir was highly effective in individuals with HCV genotype 1b infection in a large national Veterans Affairs clinical setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Real-world treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is complicated by factors that are controlled for in the clinical trial setting. |

To confirm the real-world effectiveness of elbasvir/grazoprevir (EBR/GZR), we have performed a retrospective analysis of patients from the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System with chronic HCV genotype 1b infection. |

Comorbidities among patients in this study included hypertension (74.4%), history of alcohol abuse (55.7%), and depression (54.8%). |

Ninety-eight percent of patients (3288/3371) achieved a sustained virologic response (SVR). |

What was learned from the study? |

These data confirm that the high rates of SVR achieved with EBR/GZR in clinical trials can be replicated in a heterogeneous real-world population with extensive comorbidities. |

Introduction

The receipt of and response to real-world treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with direct-acting antiviral therapy is influenced by many factors that are controlled for in the rigorous clinical trial setting. The heterogeneous population of patients with HCV infection encountered in real-world settings frequently includes individuals with comorbidities or receiving concomitant medications. In addition, the high rates of adherence attained in clinical trials are generally not achieved in real-world settings. Factors such as active alcohol consumption or active illicit drug use are frequently exclusion criteria within HCV clinical trial settings, but are often encountered when treating patients in the real world [1]. Because of these differences, the generalizability of clinical trial findings to the real-world setting is often unclear. Therefore, it is important to establish the effectiveness of direct-acting antiviral therapies in the heterogeneous population of patients with HCV infection in clinical practice.

Elbasvir/grazoprevir is an oral fixed-dose combination treatment approved in the United States, Europe, and several other countries for the treatment of HCV genotypes 1 and 4 infection [2, 3]. In clinical trials, this combination therapy has demonstrated high rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) across a broad population of people with HCV infection, including those with chronic kidney disease, inherited blood disorders, compensated cirrhosis, and HCV/HIV co-infection [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. The high SVR rates attained in elbasvir/grazoprevir clinical trials have also been replicated in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) clinical practice populations, where an SVR rate of 95.6% was achieved in a large population comprised largely of male, black participants with HCV genotype 1 (genotype 1a, 34.7%; genotype 1b, 58.6%) infection, and more than 50% of whom had a history of drug or alcohol use [11]. The aim of this study was to assess elbasvir/grazoprevir regimens in individuals with chronic HCV genotype 1b infection from the VA population. The current study population of 3371 patients includes the 1428 patients with genotype 1b infection previously reported by Kramer et al. [11], but we extended the eligibility date range to incorporate more patients with HCV genotype 1b infection. This allowed for a more robust assessment of the effectiveness of elbasvir/grazoprevir in HCV genotype 1b patients from the VA population, including examining comorbidities and receipt of concomitant medications. Furthermore, the larger dataset has allowed us, in accordance with recommendations from the European Association for Study of the Liver, to examine the effectiveness of elbasvir/grazoprevir within a sub-group of predominantly treatment-naive patients with mild liver fibrosis who received elbasvir/grazoprevir for 8 weeks.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, a national repository of data from the VA electronic medical records. The database, which is in the semi-closed healthcare system, consists of data from laboratory, pharmacy, and inpatient and outpatient clinical diagnoses. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the protocol was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board.

Patients

Patients aged ≥ 18 years with chronic HCV genotype 1b infection, who had at least 1 prescription for elbasvir/grazoprevir dispensed between February 1, 2016, and August 31, 2017 (the treatment initiation period), and who had at least 1 inpatient or outpatient visit within 1 year prior to treatment initiation, were included in the study population. Patients who had previously received treatment for HCV infection with a non-structural protein 5A (NS5A) inhibitor–containing direct-acting antiviral regimen or with an undetermined regimen or for whom HCV RNA data 4 weeks after the end of treatment for determination of SVR were not available were excluded. The index date for follow-up was defined as the first elbasvir/grazoprevir prescription date during the treatment initiation period. The elbasvir/grazoprevir regimens consisted of elbasvir/grazoprevir with or without ribavirin.

Variable Definitions

Fibrosis was assessed using the aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI), a validated, non-invasive test that uses serologic markers as an alternative to biopsy to confirm the presence of significant fibrosis or cirrhosis. An APRI score < 0.7 has been shown to indicate the absence of significant fibrosis [12]. Cirrhosis and its complications (e.g., ascites, varices, hepatic encephalopathy) were defined using International Classification of Diseases, 9th/10th revision (ICD-9/10) codes any time prior to the index date. Severity of chronic kidney disease (CKD) was based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) according to the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation [13]. We used 2 eGFR values > 90 days apart to determine stage of CKD using the following 3 groups; eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 indicating mild to no CKD, eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 corresponding to stage 3 CKD, and eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 corresponding to stage 4/5 CKD. The eGFR reading taken closest to the index date was used for classification of CKD. Other comorbid conditions present within the study population, such as diabetes, hypertension, depression, anxiety, history of alcohol and/or drug use, and HIV infection, were defined by ICD-9/10 or corresponding laboratory data any time prior to the index date. Demographic covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, other), and body mass index. The impact of concomitant medications on treatment with elbasvir/grazoprevir was assessed, specifically H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors taken during 2 weeks prior to or during the HCV treatment course. HCV treatment experience was defined as previous prescriptions dispensed by VA pharmacies for any interferon-based regimen (with or without ribavirin), the first-generation protease inhibitors boceprevir or telaprevir, or simeprevir or sofosbuvir. If patients had received more than one previous treatment regimen, they were classified based on the most recent regimen received prior to elbasvir/grazoprevir.

Analyses

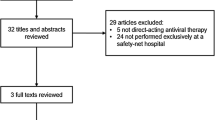

The primary analysis was conducted in the per-protocol population, which included all patients who completed their treatment course (≥ 11 weeks) and had an available HCV RNA assessment to determine SVR. Analyses were also conducted in a sub-group of patients who received elbasvir/grazoprevir prescriptions for 8 weeks. The primary outcome was SVR, defined as HCV RNA below the lower limit of quantification at 12 weeks after the end of treatment (SVR12). However, if virologic data were not available at 12 weeks after end of treatment, SVR was defined based on virologic data available post–follow-up from week 4. SVR12 data were available for 90.6% of patients in the per-protocol population and for 88.1% of those treated for 8 weeks. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine demographic and clinical factors associated with SVR (age, cirrhosis status, race/ethnicity, prior HCV treatment experience, baseline viral load, history of drug use, history of alcohol use, HIV co-infection, CKD stage, and HCV treatment regimen).

Results

A total of 3614 patients who received an elbasvir/grazoprevir-based regimen for the treatment of HCV genotype 1b infection were included. Mean age was 64.2 years (standard deviation, 6.0 years), 97.3% (n = 3516) of patients were male, 60.9% (n = 2199) were black, and 89.8% (n = 3245) were treatment-naive (Table 1). Comorbidities were common among this population: hypertension (74.4%), history of alcohol use (56.3%), and depression (54.9%) were all diagnosed in more than half of the study population (Table 2). A total of 25.5% of patients had cirrhosis, 39.0% had diabetes, 46.8% had a history of drug use, and 28.3% were taking a concomitant proton pump inhibitor. The majority of patients (89.3%) received elbasvir/grazoprevir without ribavirin for 12 weeks, and approximately 7% of patients received elbasvir/grazoprevir for 8 weeks (Table 1)

A total of 3371 patients were included in the primary per-protocol analysis. SVR was achieved by 97.5% (3288/3371) of patients in the per-protocol population, and response rates remained high across all sub-groups examined (Table 3). Notably, SVR rates were 96.0% (290/302) among patients with CKD stage 4/5, 97.8% (1527/1561) in those with a history of drug use, 97.6% (1834/1879) in those with a history of alcohol use, 98.1% (942/960) in those taking concomitant PPI medication, and 96.6% (831/860) in those with cirrhosis. Among patients who completed 12 weeks of follow-up, SVR12 rates were 97.5% (2978/3055) (Table 3).

In the logistic regression analysis, no statistically significant differences in SVR were observed in association with age, race, HCV treatment history, viral load level, treatment regimen/duration, concomitant PPI use, history of drug or alcohol use, HIV infection, or CKD. Despite the high SVR rate, cirrhosis was negatively associated with achieving SVR (p = 0.024) (Table 4).

Among treatment-naive patients, SVR rates were 95.9% (209/218) and 97.7% (2817/2883) in those treated for 8 and 12 weeks, respectively. SVR rates were also high in treatment-naive patients with an APRI score < 0.7 treated for 8 weeks (128/131, 97.7%) or 12 weeks (1708/1743, 98.0%) (Table 3). Among treatment-experienced patients, SVR was achieved by 96.5% (307/318) of those who received elbasvir/grazoprevir for 12 weeks and 100.0% (14/14) of those who received elbasvir/grazoprevir with ribavirin for 12 weeks. SVR rates were also high in treatment-experienced patients with an APRI score < 0.7 (97.2% in those receiving elbasvir/grazoprevir for 12 weeks and 100.0% in those receiving elbasvir/grazoprevir with ribavirin for 12 weeks) (Table 3).

Discussion

Data from the present analysis confirm the high effectiveness of elbasvir/grazoprevir in patients with HCV genotype 1b infection in a large nationwide VA population with considerable comorbidities, including cirrhosis, diabetes, and hypertension. Large proportions of patients in this analysis also had a history of drug or alcohol use or were taking concomitant proton pump inhibitor therapy (28.3%), which has been associated with reduced efficacy in patients receiving sofosbuvir-based regimens [14]. Within this highly heterogeneous population, SVR was achieved by 97.5% of all participants, by 97.6% of those receiving elbasvir/grazoprevir for 12 weeks, and by 97.7% of treatment-naive participants with an APRI score < 0.7 receiving elbasvir/grazoprevir for 8 weeks. An 8-week regimen of elbasvir/grazoprevir is not approved for patients with HCV infection in the United States, although the regimen is approved in some European countries. Data regarding the rationale for selecting an 8-week regimen were not collected in this study. We are also unable to determine if an 8-week regimen was intended for participants in this study or if a longer 12-week treatment duration was intended but stopped early.

Data from the present analysis are consistent with those reported previously by Kramer and colleagues [11]. This study included 2436 patients from the VA, of whom 1428 had HCV genotype 1b infection. SVR within this genotype 1b population was 96.6% (1379/1428) compared with 97.5% (3288/3371) in the present analysis. Further analysis of the genotype 1b population was not performed by Kramer and colleagues, so the influence of factors such as prior treatment history, fibrosis level, CKD, and drug or alcohol use on SVR rates in patients with HCV genotype 1b infection receiving elbasvir/grazoprevir was not established. In the present analysis, SVR rates in patients with cirrhosis were not dissimilar to the overall study population (96.6% vs. 97.5%, respectively); however, the regression analysis showed a negative association between the presence of cirrhosis and SVR. In contrast, the study by Kramer and colleagues (including patients with HCV GT1, GT2, GT3, and GT4 infection) reported similar rates of SVR in patients with and without cirrhosis. This mirrors the findings from phase 2/3 clinical trials where cirrhosis was also found to have no impact on treatment outcome [9, 15].

The present study therefore represents an important addition to the previous study, with the increased sample size permitting a detailed analysis of elbasvir/grazoprevir effectiveness in discrete patient sub-groups with HCV genotype 1b infection. The findings of the present analysis indicate that, following treatment with elbasvir/grazoprevir for 12 weeks, SVR rates are high in patients from the VA with significant comorbid conditions. These data suggest that across a wide spectrum of patients with HCV GT1b infection, a single regimen of elbasvir/grazoprevir offers a highly effective, convenient, once-daily treatment option.

The efficacy and safety of elbasvir/grazoprevir for 12 weeks in participants with HCV genotype 1b infection has been established in several phase 3 clinical trials conducted in a broad cross-section of participants with HCV genotype 1b infection. The results from these studies were summarized in an integrated analysis that included 1070 participants with HCV genotype 1b infection who received elbasvir/grazoprevir for 12 weeks [16]. Compared with the VA healthcare population described in the present analysis, the population described in the integrated analysis was predominantly white (47% vs. 30%) and included more females (50% vs. 3%). In the current VA population, the proportion of patients who were black was 61% versus 9% in the integrated analysis population. SVR was achieved by 97.2% (1040/1070) of participants included in the integrated analysis, and, of those who failed to achieve SVR, 15 had non-virologic failure and 15 experienced relapse. In the supportive per-protocol analysis (which excluded non-virologic failures), SVR was achieved by 98.6% (1040/1055) of participants, with a virologic failure rate of 1.4%. SVR rates remained high across all sub-groups of patients examined in the integrated analysis, including an SVR12 rate of 94.7% (215/227) in patients with NS5A resistance-associated substitutions at baseline [16], reinforcing the US treatment recommendation that testing for NS5A resistance-associated substitutions prior to therapy is not required for patients with HCV genotype 1b infection receiving elbasvir/grazoprevir for 12 weeks [17].

The results from the present analysis are consistent with previous reports regarding the effectiveness of elbasvir/grazoprevir in real-world, HCV-infected populations from inside and outside the United States. Toyoda et al. [18] and Ogawa et al. [19] reported SVR rates of 97.4% (371/381) and 97.5% (275/282) in Japanese patients with primarily HCV genotype 1b infection who were prescribed elbasvir/grazoprevir for 12 weeks. In both studies, most patients were treatment-naive, and approximately one-third of patients were aged ≥ 75 years and one-third had CKD stage 3–5. SVR rates were generally unaffected by baseline characteristics, including presence of cirrhosis or history of hepatocellular carcinoma; however, the presence of NS5A resistance-associated substitutions, particularly in individuals who had previously received all-oral direct-acting antiviral therapy, was associated with virologic failure [18, 19]. Similar results have also been reported in a Spanish cohort of patients with HCV genotype 1 infection, 73% of whom had genotype 1b infection [20]. In this analysis, of the 625 patients with data available at 12 weeks post-treatment, 570 (91.2%) achieved SVR12. In the modified intention-to-treat analysis, which excluded 37 patients lost to follow-up, SVR12 was 96.9% (570/588). Among the patients with HCV genotype 1b infection, SVR12 rates remained ≥ 96%, regardless of treatment history or presence of cirrhosis at baseline [20]. Data from the TRIO network in the United States further supports the high effectiveness of elbasvir/grazoprevir in patients with HCV genotype 1 infection in a real-world setting [21]. SVR12 rates in the per-protocol population were 98.5% (396/402) for patients with HCV genotype 1 infection and 99.1% (113/114) in the sub-group with CKD stage 4/5.

Our study has several strengths. First, we used data from the nationwide VA database, which is the largest integrated healthcare data source for patients with HCV infection, including those who are racially and clinically diverse. Second, missing data are relatively low because the VA healthcare system has an established electronic medical record system as well as a robust pharmacy benefits management system including prescription data across all VA facilities. Our data also indicate comparable rates of SVR compared with other HCV treatment regimens in real-world populations. SVR was achieved by 91.3% of treatment-naive veterans with HCV genotype 1 infection receiving sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and by 95.3% of treatment-naive patients with HCV genotype 1 infection from a TRIO network study [22, 23]. In a German real-world study, an SVR rate of 96.7% was attained within a treatment-naive, non-cirrhotic population with primarily HCV genotypes 1 or 3 infection receiving glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for 8 weeks [24]. The SVR rate of 97.5% attained within the present study therefore indicates that elbasvir/grazoprevir for 12 weeks is an effective treatment option for this population of patients with genotype 1b infection, offering rates of SVR that are at least broadly comparable to those seen with other second-generation DAA treatment regimens.

Our study also has certain limitations. The VA population may not be generalizable to the entire US population owing to the potential for differing demographic risk factors. Some misclassification of diagnoses and comorbidities identified through ICD-9/10 codes might have also been present. Sample sizes were small for some subgroups (e.g., those receiving elbasvir/grazoprevir with ribavirin for 16 weeks). This study also used a per-protocol population that excluded patients with less than 11 weeks’ treatment duration. These data therefore do not take into account patients who discontinue treatment early, and the reported response rates cannot be generalized to patients with shorter treatment durations. Although 8- and 12-week elbasvir/grazoprevir regimens were examined in treatment-naive and -experienced patients with HCV genotype 1b infection, the rationale for different treatment durations could not be ascertained (and, as noted earlier, the 8-week regimen is not an approved regimen for use in the United States). Additionally, some laboratory data, including NS5A resistance-associated substitutions and other factors possibly related to virologic failure, were not available. Adverse events, adherence data, and data from any treatment received outside the VA were also not available in this study.

Conclusion

Treatment with elbasvir/grazoprevir was highly effective in individuals with HCV genotype 1b infection from the VA. The data from this analysis extend the observations of elbasvir/grazoprevir efficacy and confirm that the high rates of SVR achieved in clinical trials can be replicated in a heterogeneous population with extensive comorbidities.

References

Saeed S, Strumpf EC, Walmsley SL, Roolet-Kurhajec K, Pick N, Martel-Laferniere V, et al. How generalizable are the results from trials of direct antiviral agents to people coinfected with HIV/HCV in the real world? Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(7):919–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ1222.

Zepatier [prescribing information]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme, Corp., Inc.; 2018.

Zepatier [summary of product characteristics]. Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, UK: Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd.; 2018.

Zeuzem S, Ghalib R, Reddy KR, Pockros PJ, Ben Ari Z, Zhao Y, et al. Grazoprevir-elbasvir combination therapy for treatment-naive cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients with chronic HCV genotype 1, 4, or 6 infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):1–13. https://doi.org/10.7326/m15-0785.

Kwo P, Gane E, Peng CY, Pearlman B, Vierling JM, Serfaty L, et al. Effectiveness of elbasvir and grazoprevir combination, with or without ribavirin, for treatment-experienced patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(1):164–75. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.045.

Roth D, Nelson DR, Bruchfeld A, Liapakis A, Silva M, Monsour H Jr, et al. Grazoprevir plus elbasvir in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and stage 4–5 chronic kidney disease (the C-SURFER study): a combination phase 3 study. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1537–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00349-9.

Rockstroh JK, Nelson M, Katlama C, Lalezari J, Mallolas J, Bloch M, et al. Efficacy and safety of grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK-8742) in patients with hepatitis C virus and HIV co-infection (C-EDGE CO-INFECTION): a non-randomised, open-label trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(8):e319–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00114-9.

Hezode C, Colombo M, Bourliere M, Spengler U, Ben-Ari Z, Strasser SI, et al. Elbasvir/grazoprevir for patients with hepatitis C virus infection and inherited blood disorders: a phase III study. Hepatology. 2017;66(3):736–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29139.

Jacobson IM, Lawitz E, Kwo PY, Hezode C, Peng CY, Howe AYM, et al. Safety and efficacy of elbasvir/grazoprevir in patients with hepatitis C virus infection and compensated cirrhosis: an integrated analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1372–1382.e2. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.050.

Asselah T, Reesink H, Gerstoft J, de Ledinghen V, Pockros PJ, Robertson M, et al. Efficacy of elbasvir and grazoprevir in participants with hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection: a pooled analysis. Liver Int. 2018;38(9):1583–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13727.

Kramer JR, Puenpatom A, Erickson KF, Cao Y, Smith D, El-Serag HB, et al. Real-world effectiveness of elbasvir/grazoprevir in HCV-infected patients in the US veterans affairs healthcare system. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(11):1270–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.12937.

Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11):807–20. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00005.

National Kidney Foundation. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1–150.

Terrault NA, Zeuzem S, Di Bisceglie AM, Lim JK, Pockros PJ, Frazier LM, et al. Effectiveness of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir combination in patients with hepatitis C virus infection and factors associated with sustained virologic response. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(6):1131–40. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.004.

Jacobson IM, Poordad F, Firpi-Morell R, Everson GT, Verna EC, Bhanja S, et al. Elbasvir/grazoprevir in people with hepatitis C genotype 1 infection and Child-Pugh class B cirrhosis: the C-SALT Study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10(4):e00007. https://doi.org/10.14309/ctg.0000000000000007.

Zeuzem S, Serfaty L, Vierling J, Cheng W, George J, Sperl J, et al. The safety and efficacy of elbasvir and grazoprevir in participants with hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(5):679–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-018-1429-3.

AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2018 Update: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(10):1477–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy585.

Toyoda H, Atsukawa M, Takaguchi K, Senoh T, Michitaka K, Hiraoka A, et al. Real-world virological efficacy and safety of elbasvir and grazoprevir in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(12):1276–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-018-1473-z.

Ogawa E, Furusyo N, Azuma K, Nakamuta M, Nomura H, Dohmen K, et al. Elbasvir plus grazoprevir for patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1: a multicenter, real-world cohort study focusing on chronic kidney disease. Antiviral Res. 2018;159:143–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.10.003.

Hernandez-Conde M, Fernandez I, Perello C, Gallego A, Bonacci M, Pascasio JM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of elbasvir/grazoprevir therapy in patients with chronic HCV infection: results from the Spanish HEPA-C real-world cohort. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26(1):55–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.13008.

Flamm SL, Bacon B, Curry MP, Milligan S, Nwankwo CU, Tsai N, et al. Real-world use of elbasvir-grazoprevir in patients with chronic hepatitis C: retrospective analyses from the TRIO network. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(11):1511–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14635.

Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Loomis TP, Mole LA. Real-world effectiveness of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir in 4,365 treatment-naive, genotype 1 hepatitis C-infected patients. Hepatology. 2016;64(2):405–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28625.

Curry MP, Tapper EB, Bacon B, Dieterich D, Flamm SL, Guest L, et al. Effectiveness of 8- or 12-weeks of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir in real-world treatment-naive, genotype 1 hepatitis C infected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(5):540–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14204.

Berg T, Naumann U, Stoehr A, Sick C, John C, Teuber G, et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection: data from the German Hepatitis C-Registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(8):1052–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.15222.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. The costs associated with the Rapid Service Fees of this manuscript were paid by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.The research reported here was supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development Service(VA IIR 13-059). Drs Kramer, El-Serag, and Kanwal are Research Health Scientists at the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (#CIN 13-413), Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, TX. This work is also partly funded by NIH grant T32 DK083266-01A1, NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease to Hashem B. El-Serag and Center Grant P30 DK56338.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Tim Ibbotson, PhD, of ApotheCom (Yardley, PA, USA) and funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Authorship

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

These data were presented at The Liver Meeting® 2018; San Francisco, CA; November 9–13, 2018; abstract number 660. Puenpatom A et al. Hepatology. 2018;68(suppl 1):392A.

Disclosures

Dr Amy Puenpatom is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, and shareholder in Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. Dr Jennifer Kramer has received grant support from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. Dr Fasiha Kanwal has received grant support from Gilead and from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. Yumei Cao and Xian Yu have nothing to disclose. Dr Hashem El-Serag has received grant support from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the protocol was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board.

Data Availability

All aggregated analyses tables generated during this study are included in this published article. De-identified patient level datasets generated and/or analyzed in the study are not available due to the restrictions from the VA not to release patient-level data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11974353.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Puenpatom, A., Cao, Y., Yu, X. et al. Effectiveness of Elbasvir/Grazoprevir in US Veterans with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 1b Infection. Infect Dis Ther 9, 355–365 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00293-7

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00293-7