Abstract

Introduction

This study assessed the association between early initiation of eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL) as first-line therapy (1L cohort) or as first adjunctive regimen to either levetiracetam (LEV) or lamotrigine (LTG) (add-on cohort), and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and charges among adults with treated focal seizures (FS).

Methods

This retrospective, longitudinal cohort analysis used Symphony Health’s Integrated Dataverse (IDV®) claims data to identify patients aged ≥ 18 years with a diagnosis of FS who had a new prescription for ESL between April 2015 and June 2018. Baseline was the 90-day period immediately prior to the date of the first-dispensed claim for ESL (index date) with a follow-up of 1–4 consecutive 90-day periods. Linear regression models were estimated to assess changes in HCRU and charge outcomes.

Results

There were 274 and 153 patients who received ESL in the 1L cohort and add-on cohort, respectively. The 1L cohort experienced significant reductions from baseline during follow-up in all-cause inpatient (IP; P < 0.0001), emergency room (ER; P < 0.0001), and outpatient (OP; P < 0.0001) visits; FS-related IP (P = 0.006) and OP (P < 0.0001) visits; total, medical, all-cause ER and OP, and FS-related medical charges (P < 0.05); and significant increases in total prescription and anti-seizure drug (ASD)-related prescription (P < 0.001) charges. The add-on cohort experienced significant reductions in all-cause IP (P = 0.009) and all-cause and FS-related OP visits (P < 0.0001 for both) and significant increases in total prescription and ASD-related prescription (P < 0.001) charges during the follow-up period. In both cohorts, the increases in prescription charges were smaller than the reduction in total medical charges.

Conclusion

Early initiation of ESL as 1L or add-on therapy was associated with statistically significant reductions in all-cause IP and all-cause and FS-related OP visits during follow-up compared to baseline. The 1L cohort also had statistically significant reductions in all-cause ER visits, FS-related IP visits, and total, medical, all-cause ER and OP, and FS-related medical charges.

Plain Language Summary

Knowledge of healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and costs of care in patients taking anti-seizure drugs (ASDs) is required to inform prescribing and formulary decision-making. Levetiracetam (LEV) and lamotrigine (LTG) are the most widely used first-line (1L) ASDs in the USA. Eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL), a third-generation ASD with sodium channel-modulating activity, is typically used in later lines of therapy. Sodium channel-blocking anti-seizure drugs may represent an effective treatment option for patients with epilepsy in the 1L setting. This study assessed the association between early initiation of ESL as 1L therapy (1L cohort) or as first adjunctive therapy to either LEV or LTG (add-on cohort), and HCRU and charges among adults with treated focal seizures (FS). The results showed that following ESL initiation the 1L cohort experienced significant reductions in all-cause inpatient (IP), emergency room (ER), and outpatient (OP) visits; FS-related IP and OP visits; and total, medical, all-cause ER and OP, and FS-related medical charges, and significant increases in total prescription and ASD-related prescription charges. The add-on cohort showed significant reductions in all-cause IP and all-cause and FS-related OP visits and significant increases in total prescription and ASD-related prescription charges. In both cohorts, the increases in prescription charges were smaller than the reduction in total medical charges. These data imply that use of ESL as 1L therapy in adult patients with FS could help conserve scarce healthcare resources and reduce the burden on healthcare budgets. These findings may inform selection of ASD therapy in this patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL), a third-generation anti-seizure drug, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of partial onset seizure (focal seizure, FS) in patients aged ≥ 4 years. |

No data are currently available that examine economic outcomes after the early initiation of ESL in routine clinical practice. |

What did the study ask?/What was the hypothesis of the study? |

This study investigated the association between early ESL initiation, either as first-line therapy (1L) or as adjunctive therapy to either levetiracetam or lamotrigine, and healthcare resource utilization and charges in adult patients with focal seizures. |

What were the study outcomes/conclusions? |

Early initiation of ESL as 1L or adjunctive therapy was associated with significant reductions in all-cause inpatient and all-cause and FS-related outpatient visits in the follow-up period compared to baseline. |

Early initiation of ESL as 1L therapy was also associated with significant reductions in all-cause emergency room visits, FS-related inpatient visits, and total medical, all-cause emergency room and outpatient, and FS-related medical charges. |

What has been learned from the study? |

This study showed that the early initiation of ESL either as first-line or as first add-on therapy was associated with better economic outcomes in adult patients with FS. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12906863.

Introduction

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder that is characterized by unprovoked, recurrent seizures. In the USA, epilepsy affects 1.2% of the total population and approximately 3 million adults [1]. Of the several types of epileptic seizures, focal seizures (FS) are the most common (60%) [2, 3]. The main goal of epilepsy therapy is to eliminate seizures and maintain or improve quality of life. The choice of epilepsy therapy is driven by a drug’s efficacy, tolerability, and safety [4]. Three generations of anti-seizure drugs (ASDs) are currently used to manage FS [5]. Levetiracetam (LEV) and lamotrigine (LTG), which are second-generation ASDs, are the most widely used first-line (1L) ASDs in the USA [6]. Third-generation ASDs are typically used in later lines of therapy [5, 7].

Eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL), a third-generation ASD, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2013 for the treatment of partial-onset seizure (FS) in adult patients [8]. The efficacy and safety of ESL as an adjunctive therapy or as monotherapy for FS have been demonstrated in several randomized, controlled clinical trials [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. However, most of these clinical trials were conducted in later lines of treatment [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]; consequently, information on early use of ESL is lacking. Only one open-label, phase IV study in a real-world setting has assessed the efficacy and safety of ESL as the first adjunctive therapy or as later adjunctive therapy in patients with FS [17, 18]. The findings showed efficacy and tolerability for ESL as first adjunctive therapy with LEV or LTG, consistent with results from phase III clinical trials in patients using ESL as later adjunctive therapy following use of one to three ASDs [17, 18].

Evidence suggests that sodium channel-blocking anti-seizure drugs (NABs), a class of which ESL is a member, may represent an effective treatment option for patients with FS in the 1L setting. The Human Epilepsy Project studied untreated patients with epilepsy who were randomly assigned to receive a NAB or LEV [19]. Compared to patients receiving LEV, those treated with NABs experienced improved 6-months seizure freedom and lower rates of an addition of or a switch to a second ASD to achieve improved outcomes [19]. A phase III study demonstrated noninferiority for once-daily ESL in the 1L setting compared to twice-daily, controlled-release carbamazepine (CBZ-CR) monotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with FS; the effects of ESL were maintained over the 1-year treatment duration [20]. Another study reported large reductions in FS at 3, 6, and 12 months in patients with epilepsy who were transitioned to ESL in three ways: initial monotherapy (ESL-naïve and not taking any other ASDs), switch therapy (previously taking CBZ or oxcarbazepine and switched to ESL), and conversion to monotherapy (taking ≥ 1 ASD, including ESL, and converted to ESL monotherapy) [21]. At 12 months, most patients in the initial monotherapy group and the conversion to monotherapy group achieved a ≥ 50% reduction in seizure frequency (75.0 and 89.7%, respectively) or were seizure-free (68.7 and 66.6%, respectively).

No data are available that examine economic outcomes, such as healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) or direct costs, after the early initiation of ESL in routine clinical practice. The objective of this study was to assess the association between early initiation of ESL as 1L therapy or as first adjunctive therapy to either LEV or LTG, and HCRU and charges among adults with treated FS.

Methods

Data Source

The analytic dataset was constructed from Symphony Health’s Integrated Dataverse® (IDV®) open-source claims database that includes pharmacy claims, physician office medical claims, and hospital claims from an estimated 274 million patients in the USA. Collected data included patient characteristics, medical resource use, diagnoses, procedures, prescription fills, and charges for visits to covered providers from 1st April 2015 through 30th June 2018. IDV® data were de-identified in compliance with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Therefore, this study did not constitute Human Subjects Research, and review by an institutional review board was not required (US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington DC, USA).

Study Design

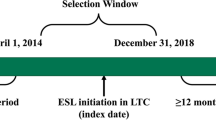

This retrospective, longitudinal cohort analysis included a pre- and post-treatment comparison of the early initiation of ESL in two separate cohorts: (1) ESL as 1L treatment (1L cohort); and 2) ESL as first adjunctive regimen to either LEV or LTG (add-on cohort) (Fig. 1). A longitudinal panel data approach was used, and the unit of analysis was a person-specific period of 90 consecutive days. Patients were assigned an index date corresponding to the date of their first dispensed claim for ESL. The baseline period was defined as the 90-day period immediately prior to the index date [22]. The follow-up period was defined as at least 1 and up to 4 consecutive 90-day periods immediately following the index date. The main analyses averaged outcomes over the follow-up 90-day periods. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted that stratified the four 90-day follow-up periods to ensure that costs per block were not artificially reduced by averaging the results over time.

Patient Population

Patients were included in the analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) resident of the USA; (2) ≥ 1 medical claim with a primary or nonprimary diagnosis of FS (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD-9], Clinical Modification codes 345.4x or 345.5x or ICD-10 codes G40.1x or G40.2x); (3) ≥ 1 dispensed pharmacy claim for an ASD; (4) ≥ 1 dispensed pharmacy claim for ESL with the earliest dispensed ESL claim coded as a new prescription (index date); (5) earliest dispensed ASD claim for ESL in the 1L cohort, or for LEV or LTG in the add-on cohort; (6) ≥ 6 months from the start of data coverage (1st April 2015) to the earliest dispensed ESL claim; (7) ≥ 18 years of age at the index date; (8) ≥ 3 months of data coverage prior to and following the index date; (9) ≥ 1 medical claim with an FS diagnosis prior to or within 12 months after the index date; and (10) ≥ 1 medical claim and pharmacy claim during the 3-month baseline period and at any time following the index date (Fig. 2).

Sample selection. aExcludes patients residing in Puerto Rico and the US territories, or those with missing/invalid data. bPatients were included in the data extract only if they had ≥ 1 focal seizure diagnosis and an ASD claim (approved, rejected, or reversed). cFocal seizure was defined as ICD-9-CM codes 345.4x or 345.5x or ICD-10 codes G40.1x or G40.2x. dOnly birth year was available, so all patients were assigned a birthdate of 1 July for the purpose of calculating age. eDefined as ICD-9-CM codes V22.x, V23.xx, or 630–679.xx or ICD-10 codes Z33*–Z36*, or O00*–O99*. ASD Anti-seizure drug, ICD-9-CM International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, ESL eslicarbazepine acetate, LEV levetiracetam, LTG lamotrigine

Additional selection criteria for the add-on cohort included: (1) ≥ 28 consecutive days with possession of LEV or LTG immediately prior to the index date; (2) existing days’ supply of LEV or LTG as of the index date and a subsequent claim for LEV or LTG within 30 days of exhaustion of the supply; (3) ≥ 6 months from the start of data coverage to the start of the 28-day period prior to the index date; and (4) no dispensed claim for any other ASD prior to the index date (Fig. 2).

Study Measures

Baseline Demographics

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were measured during the 90-day period immediately preceding the index date. Demographic characteristics included age, gender, and payer type (commercial, Medicaid, Medicare, cash/assistance programs). Clinical characteristics included comorbidities such as medical disorders, neurological disorders, and developmental and/or psychiatric disorders.

ASD-related characteristics measured on index date included dose-per-day and patient copay amount for the initial ESL prescription, and adjunctive or monotherapy. Dose-per-day was based on the strength, quantity dispensed, and days of supply of the index ESL claim. For the 1L cohort, patients were defined as receiving ESL as adjunctive therapy if they also had a claim for a non-ESL ASD on their index date. The add-on cohort had ESL as adjunctive therapy according to the criteria used in the sample selection.

HCRU and Associated Charges

All HCRU data were examined at baseline and follow-up (pre- and post-ESL initiation) and presented as the proportion of patients with ≥ 1 HCRU visit by location of care. HCRU measures included the proportion of all-cause or FS-related inpatient (IP), emergency room (ER), and outpatient (OP) visits. All-cause HCRU was defined as HCRU due to any cause. FS-related HCRU was defined as HCRU with a diagnosis of FS in any diagnosis position associated with that claim.

All data on all-cause and FS-related charges associated with specific claim types were collected at baseline and follow-up (pre- and post-ESL initiation), including charges for IP, ER, and OP visits; total charges; total and FS-related medical charges; and total, ASD-, and non-ASD-related prescription charges.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as means and standard deviations (SD). Dichotomous and categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages.

Separate linear regression models with person-specific fixed effects were estimated to assess within-person changes in HCRU and charges between baseline and follow-up for each independent cohort. For each cohort, separate models were run for the all-cause and FS-related HCRU category and charge outcomes. Each model estimated the average absolute reduction in HCRU and charges per 90-day period relative to the baseline period. Two models were run, one combining all 90-day periods during follow-up and the other stratified by 90-day follow-up period. Pre-post changes in outcomes were quantified directly from the coefficient(s) on a binary indicator for the post period or a categorical indicator for each block (with the pre-period block serving as the omitted referent). A Wald test was used to test whether a coefficient was equal to zero. Model standard errors were made robust to heteroskedasticity and adjusted for the clustering of multiple periods per patient.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Stata MP software version 16 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Two-sided statistical tests were used, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 274 and 153 patients met the study inclusion criteria (Fig. 2) and received ESL in the 1L (n = 274) or add-on (n = 153) cohort, respectively. The baseline and clinical characteristics of the two independent cohorts are described in Table 1.

In the 1L cohort, mean (± SD) patient age was 48.1 (± 16.0) years, 42.0% of patients were male, and 93.8% received ESL as monotherapy. The prevalence rates of comorbidities were 67.9, 42.7, and 21.9% for medical, neurological, and developmental and/or psychiatric disorders, respectively. The majority of patients were enrolled in commercial insurance (58.4%), followed by Medicaid (17.5%) and Medicare (17.2%), while the remaining patients relied on cash and assistance programs. The mean (± SD) patient copay amount was $74 (± $166). On the index date, the mean (± SD) dose-per-day of ESL was 693.3 mg (± 313.7 mg), and 44.5% of patients received ESL 800 mg.

In the add-on cohort, mean (± SD) patient age was 44.9 (± 16.5) years, and 43.1% of patients were male (Table 1). The prevalence of comorbidities was 57.5, 36.6, and 22.2% for medical, neurological, and developmental and/or psychiatric disorders, respectively. The majority of patients were enrolled in commercial insurance (52.9%), followed by Medicaid (20.3%) and Medicare (15.7%), while the remaining patients relied on cash and assistance programs. The mean (± SD) patient copay amount was $129 (± $424). On the index date, the mean (± SD) dose-per-day of ESL was 658.2 mg (± 287.5 mg), and 39.2% of patients received ESL 800 mg.

HCRU and Associated Charges in the 1L Cohort

Adjusted HCRU for patients with FS initiating ESL as 1L treatment is shown in Fig. 3a and Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Fig. S1a. There were statistically significant reductions in all-cause IP (− 9.6 percentage points [ppts]; P < 0.0001), ER (− 19.0 ppts; P < 0.0001), and OP (− 23.2 ppts; P < 0.0001) visits and FS-related IP (− 4.4 ppts; P = 0.006) and OP (− 18.9 ppts; P < 0.0001) visits in the follow-up period compared to baseline. There was a statistically significant increase in FS-related ER visits (0.8 ppts; P = 0.02).

Changes in HCRU (a) and associated charges (b) in patients taking ESL as 1L in the follow-up period compared to baseline. All results are from adjusted analyses. Asterisk (red) denotes a significant result at P < 0.05. ER Emergency room FS focal seizure, HCRU healthcare resource utilization, IP inpatient, OP outpatient, ppts percentage points, USD United States dollars

Adjusted charges for patients with FS initiating ESL as 1L treatment are shown in Fig. 3b and ESM Fig. S1b. There were statistically significant reductions in total (− $2249; P = 0.02), medical (− $4076; P < 0.0001), all-cause ER (− $1154; P = 0.001), all-cause OP (− $2447; P = 0.002), and FS-related medical (− $1014; P = 0.041) charges in the follow-up period compared to baseline. There were statistically significant increases in total prescription ($1827; P < 0.0001) and ASD-related prescription ($1930; P < 0.0001) charges in the follow-up period compared to baseline. Numerical but statistically nonsignificant reductions were observed in all-cause IP charges, FS-related IP and OP charges, and non-ASD-related prescription charges. The increases in prescription charges were of lower magnitude than the reduction in total medical charges.

HCRU and charges in each 90-day period during follow-up versus baseline for patients with FS initiating ESL as 1L treatment are described in ESM Table S1. There were statistically significant reductions in all-cause IP (P < 0.001), ER (P < 0.001), and OP (P < 0.001) visits, and FS-related IP (P < 0.05) and OP (P < 0.001; except for the first 90-day period) visits in each 90-day period during follow-up compared to baseline. There were statistically significant reductions in total charges (P < 0.05; except for the first 90-day period), medical charges (P < 0.01), and all-cause ER (P < 0.05) and OP charges (P < 0.05; except for the first 90-day period) in each 90-day period during follow-up compared to baseline. There were statistically significant increases in total prescription (P < 0.0001) and ASD-related prescription (P < 0.001) charges in each 90-day period during follow-up compared to baseline.

HCRU and Associated Charges in Add-on Cohort

Adjusted HCRU for patients with FS initiating ESL as add-on to LEV or LTG treatment are shown in Fig. 4a and ESM Fig. S2a. There were statistically significant reductions in all-cause IP (− 9.5 ppts; P = 0.009) and all-cause and FS-related OP (− 23.4 and − 21.6 ppts, respectively; P < 0.0001 for both) visits in the follow-up period compared to baseline. Numerical but statistically nonsignificant reductions were observed in all-cause ER and FS-related IP and ER visits.

Changes in HCRU (a) and associated charges (b) in patients taking ESL as add-on treatment to either to either LEV or LTG in the follow-up period compared to baseline. All results are from adjusted analyses. Asterisk (red) denotes a significant result at P < 0.05. ASD anti-seizure drug, ER emergency room, ESL eslicarbazepine acetate, FS focal seizure, HCRU healthcare resource utilization, IP inpatient, LEV levetiracetam, LTG lamotrigine, OP outpatient, ppts percentage points, Rx prescription, USD United States dollars

Adjusted charges for patients with FS initiating ESL as add-on to LEV or LTG treatment are shown in Fig. 4b and ESM Fig. S2b. Numerical but statistically nonsignificant reductions were observed in total charges, medical and FS-related medical charges, all-cause and FS-related IP, ER, and OP charges, and non-ASD-related prescription charges in the follow-up period compared to baseline. There were statistically significant increases in total prescription ($1796; P < 0.001) and ASD-related prescription ($1964; P < 0.001) charges. The increases in prescription charges were of lower magnitude than the reduction in total medical charges.

HCRU and charges in each 90-day period during follow-up versus baseline for patients initiating ESL as add-on treatment to LEV or LTG are described in ESM Table S2. There were statistically significant reductions in all-cause IP (P < 0.05; except for first 90-day period) and OP (P < 0.001) visits, and in FS-related OP (P < 0.001) visits in each 90-day period during follow-up compared to baseline. There were statistically significant reductions in FS-related OP charges (P < 0.05; except for first 90-day period) in each 90-day period during follow-up compared to baseline. There were statistically significant increases in total prescription (P < 0.0001) and ASD-related prescription (P < 0.001) charges in each 90-day period during follow-up compared to baseline.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that early initiation of ESL as 1L treatment or adjunctive therapy to LEV or LTG in adults with FS was associated with a beneficial economic impact, as demonstrated by significant reductions in HCRU and charges associated with specific claim types. Increases in prescription charges were of lower magnitude than decreases in all types of HCRU-associated charges. The evidence of improvement in economic outcomes was seen in patients who initiated ESL as 1L treatment or as add-on therapy, but more outcomes reached statistical significance in patients initiating ESL as 1L treatment.

In the present study, the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who initiated ESL in the 1L cohort or later in the treatment cycle were comparable [23]. In contrast, patients with incident FS from another retrospective study were younger (mean age 36.0 years), and the most common comorbidities were hypertension (not otherwise specified 21.1%), mood (11.6%), and anxiety (10.8%) [6]. Further, a large percentage of these patients (44.4%) received generic LEV as their 1L agent. Thus, patients receiving ESL as 1L therapy appear to be older with a higher comorbidity burden than patients initiating generic ASDs such as LEV. Although based on studies with small sample sizes, one possible explanation may be that physicians are triaging older patients with more comorbidities to ESL, perhaps based on its perceived tolerability and drug interaction profile compared to generic ASD options [24].

To date, only one previous study reported HCRU prior to and following the initiation of ESL in adult patients with FS [23]. The results from the present study support this prior retrospective claims database analysis that described IP admissions, ER visits, and OP hospital or clinic visits in patients receiving ESL as adjunctive treatment (n = 332) or monotherapy (n = 164) following medians of three and two prior ASDs, respectively. Patients in the adjunctive treatment group experienced statistically significant decreases in all-cause ER visits (baseline to follow-up: 36.1 to 28.0%; P = 0.002) and OP hospital or clinic visits (81.0 to 75.6%; P = 0.036). Patients in the monotherapy group experienced statistically significant decreases across the all-cause HCRU categories (P < 0.05) and for epilepsy-related ER visits (15.9 to 8.5%; P = 0.023) and OP hospital or clinic visits (47.6 to 35.4%; P = 0.018) [23].

The clinical benefits of early initiation of ESL may be driving the economic benefits observed in the current study [17, 18]. In the Human Epilepsy Project, 50 patients with newly treated focal epilepsy who initiated a NAB (drug with inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels as a potential mechanism of action, similar to ESL) had better 6-month (61 vs. 37%) and terminal seizure freedom (52 vs. 30%) compared to those who initiated LEV monotherapy. Additionally, 85% of patients receiving LEV often required addition of or transition to a NAB to achieve improved outcomes [19]. In the open-label, non-randomized, multicenter phase IV study, adjunctive ESL was evaluated in two arms: ESL as a first adjunctive therapy with LEV or LTG (Arm 1, n = 44) or ESL as later adjunctive therapy in treatment-resistant patients (Arm 2, n = 58) [17]. At 24 weeks, patients in Arm 1 reported high median reductions in standardized seizure frequency (72.8%) and high responder rates (62.5%); there was also a high proportion of seizure-freedom in patients in Arm 1 (25.0 vs. 9.6%; the study was not powered to compare arms) [17]. Treatment-emergent adverse events were more frequently reported in Arm 2 (81%) than in Arm 1 (73%) [17].

Study Strengths

The study has several strengths, including the use of claims data that were obtained from multiple insurance and payer types, supporting the generalizability of the study findings to the US adult population of patients with FS. Fixed-effects models were employed in the statistical analysis to remove the influence of all time-invariant confounders, and comparison groups were intrinsically similar because of the within-person identification strategy.

Study Limitations

The study has several limitations. Symphony IDV® is an open-source database and may not capture all claims for a patient. The database only lists the primary payer type and thus does not contain information about secondary payers. Symphony IDV® reports only submitted charges, which do not reflect paid amounts or costs faced by the provider. The pre-post study design did not eliminate confounding by other within-patient longitudinal factors, specifically adherence. The longitudinal panel data analytic approach may have been affected by regression to the mean. However, sensitivity analyses that stratified each 90-day period showed consistent reductions in HCRU and charges in the first, second, third, and fourth periods, alleviating this concern to some extent.

Conclusions

Early initiation of ESL in the 1L or add-on cohort was associated with statistically significant reductions in all-cause IP and all-cause and FS-related OP visits in the follow-up period compared to baseline. The 1L cohort also had statistically significant reductions in all-cause ER visits; FS-related IP visits; and total, medical, all-cause ER and OP, and FS-related medical charges. Further investigations into the relationship between early ESL initiation and the impact on healthcare expenditures and clinical outcomes in patients with FS are warranted.

References

Zack MM, Kobau R. National and state estimates of the numbers of adults and children with active epilepsy—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(31):821–5.

Beghi E. The epidemiology of epilepsy. Neuroepidemiol. 2020;54(2):185–91.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The epilepsies and seizures: Hope through research, https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Hope-Through-Research/Epilepsies-and-Seizures-Hope-Through; 2020. Accessed 23 July 2020.

French JA, Gazzola DM. New generation antiepileptic drugs: what do they offer in terms of improved tolerability and safety? Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2011;2(4):141–58.

Besag FM, Patsalos PN. New developments in the treatment of partial-onset epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012;8:455–64.

Faught E, Helmers S, Thurman D, Kim H, Kalilani L. Patient characteristics and treatment patterns in patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy: a US database analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;85:37–44.

Kanner AM, Ashman E, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline update summary: efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs II: treatment-resistant epilepsy: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2018;91(2):82–90.

Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. APTIOM® (eslicarbazepine acetate) prescribing information. Revised March 2019. https://www.aptiom.com/Aptiom-Prescribing-Information.pdf. Accessed July 2020.

Gil-Nagel A, Lopes-Lima J, Almeida L, Maia J, Soares-da-Silva P, BIA-2093-303 Investigators Study Group. Efficacy and safety of 800 and 1200 mg eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive treatment in adults with refractory partial-onset seizures. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;120(5):281–7.

Ben-Menachem E, Gabbai AA, Hufnagel A, Maia J, Almeida L, Soares-da-Silva P. Eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive therapy in adult patients with partial epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2010;89(2–3):278–85.

Halasz P, Cramer JA, Hodoba D, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate: results of a 1-year open-label extension study in partial-onset seizures in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2010;51(10):1963–9.

Hufnagel A, Ben-Menachem E, Gabbai AA, Falcao A, Almeida L, Soares-da-Silva P. Long-term safety and efficacy of eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of partial-onset seizures in adults with epilepsy: results of a 1-year open-label extension study. Epilepsy Res. 2013;103(2–3):262–9.

Jacobson MP, Pazdera L, Bhatia P, et al. Efficacy and safety of conversion to monotherapy with eslicarbazepine acetate in adults with uncontrolled partial-onset seizures: a historical-control phase III study. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:46.

Sperling MR, Abou-Khalil B, Harvey J, et al. Eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive therapy in patients with uncontrolled partial onset seizures: results of a phase III, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2015;56(2):244–53.

Sperling MR, Harvey J, Grinnell T, Cheng H, Blum D, 045 Study Team. Efficacy and safety of conversion to monotherapy with eslicarbazepine acetate in adults with uncontrolled partial-onset seizures: a randomized historical-control phase III study based in North America. Epilepsia. 2015;56(4):546–55.

Pazdera L, Sperling MR, Harvey JH, et al. Efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate monotherapy in patients converting from carbamazepine. Epilepsia. 2018;59(3):704–14.

Cantu D, Gidal BE, Tosiello R, Blum D, Pikalov A, Grinnell T. Safety and tolerability of eslicarbazepine acetate as first adjunctive therapy with levetiracetam or lamotrigine, or as later adjunctive therapy in patients with focal seizures. American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting. Baltimore (MD): 6–10 December 2019; Abstract 1.427.

Pikalov A, Grinnell T, Hixson J, Tosiello R, Blum D, Cantu D. Efficacy of eslicarbazepine acetate as first adjunctive therapy with levetiracetam or lamotrigine, or as later adjunctive therapy in patients with focal seizures. American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting, Baltimore, 6–10 December 2019. Abstract 1.45.

Lloyd-Smith A, Hennessy R, Hegde M, Gidal B, French J. Comparison of levetiracetam versus sodium channel blockers as first line antiepileptic drug in participants with high seizure burden using Human Epilepsy Project data. American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting, Houston, 2–6 December 2016. Abstract 2.103.

Trinka E, Ben-Menachem E, Kowacs PA, et al. Efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate versus controlled-release carbamazepine monotherapy in newly diagnosed epilepsy: a phase III double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2018;59(2):479–91.

Toledano R, Jovel CE, Jimenez-Huete A, et al. Efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate monotherapy for partial-onset seizures: Experience from a multicenter, observational study. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;73:173–9.

Mehta D, Davis M, Epstein AJ, Williams GR. Healthcare resource utilization pre- and post-initiation of eslicarbazepine acetate among pediatric patients with focal seizure: evidence from routine clinical practice. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:379–87.

Mehta D, Lee A, Simeone J, Rajogapalam K, Carroll R, Nordstrom B. Characteristics of adult patients with focal seizure receiving eslicarbazepine acetate therapy in routine clinical practice: Evidence from a large US commercial claims database. American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting, New Orleans, 30 November–4 December 2018. Abstract 2.263.

Glauser T, Ben-Menachem E, Bouregois B, et al. Updated ILAE evidence review of antiepileptic drug efficacy and effectiveness as initial monotherapy for epileptic seizures and syndromes. Epilepsia. 2013;54(3):551–63.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was sponsored by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. Sunovion participated in the study design, analysis and interpretation of data, and review and approval of the manuscript to submit for publication. Funding for manuscript development and the journal’s Rapid Service Fees was provided by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Jane Kondejewski, PhD of SNELL Medical Communication Inc. Funding for medical writing support was provided by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosure

Darshan Mehta is an employee of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. Matthew Davis is an employee of Medicus Economics, LLC, which received funding from the study sponsor to participate in this research. Andrew J Epstein is an employee of Medicus Economics, LLC, which received funding from the study sponsor to participate in this research. Brian Wensel is an employee of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. Todd Grinnell is an employee of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. G Rhys Williams is an employee of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Compliance with Ethic Guidelines

IDV® data are de-identified in compliance with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Therefore, this study did not constitute Human Subjects Research, and review by an institutional review board was not required (US Department of Health and Human Services).

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to a licensing agreement with Symphony Health’s Integrated Dataverse®.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12906863.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehta, D., Davis, M., Epstein, A.J. et al. Impact of Early Initiation of Eslicarbazepine Acetate on Economic Outcomes Among Patients with Focal Seizure: Results from Retrospective Database Analyses. Neurol Ther 9, 585–598 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-020-00211-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-020-00211-6