Abstract

Charles S. Peirce’s philosophy of signs, generally construed as the foundation of current semiotic theory, offers a theory of general perception with significant implications for the notion of subjectivity in organisms. In this article, we will discuss Peirce’s primary claims in semiotic theory, particularly focusing on their relevance to biosemiotics. We argue that these claims align with certain areas of the philosophy of biology, specifically epistemological and ontological considerations, despite the limited formal interaction between disciplines. This article serves as a general introduction to Peircean biosemiotics as a philosophical perspective on biological subjectivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Charles Peirce’s philosophy, and particularly his work on signs and representation, has been profoundly influential in the development of current semiotic theories. His work has in fact allowed the coining of some important analytical tools in terms of the so-called generality of the sign and its use in communication theory and in cultural analysis. An area of semiotics where this has been particularly true is biosemiotics, a more or less novel field where Peirce’s theoretical abstractions have made an even bigger impact in the objects of its research, methodology, and theory building (Favareau 2008). In this article we will examine some of the central notions of Peirce’s semiotics as related to the development of biosemiotics and its current state, what his concepts do for biosemiotics, and the consequences of such an approach. This, we will argue, has relevant overlap with some of the areas of the philosophy of biology, offering an avenue of interaction yet to be fully explored. This is particularly true regarding questions about causality in evolution from the perspective of niche construction, the way life can be defined as contiguous with perception—that is, what are the properties of living systems—and how we can analyze whether there is subjectivity and experience in different kinds of organisms, regardless of their complexity. Biosemioticians, as we will see, defend the place of a kind of subjectivity enabled by the usage of signs that will bear insightful views about these questions.

Drawing from Peirce’s philosophy, biosemiotics presents an intriguing challenge to reductive physicalismFootnote 1 by emphasizing the role of organisms as agents and of semiosis as an explanatory factor for biological processes. Building upon this understanding, our article aims to explore Peirce’s philosophical claims used by biosemioticians to characterize the role of semiosis and subjectivity in biological explanations and elucidate the potential fruitfulness of this perspective from a philosophical standpoint. In the subsequent sections, we will look at what semiotics does, tracing some relevant historical questions that allow us to see Peirce’s thought with more clarity, at least with respect to the usage of his philosophy in semiotics. Subsequently, we will analyze the claims put forth by biosemioticians, rooted in Peirce’s ideas, and explore the extent to which these claims may overlap with the philosophy of biology, in its more conceptual sense.

Semiotics and Biosemiotics

Semiotics, generally construed as the doctrine of signs (Deely 2006), can also be thought of as “a theory of significatory processes, communicative and non-communicative” (Cobley 2010, p. 10) or even as a discipline that studies the things that can be used for lying (Eco 1976). Though full of varieties and subdisciplines, semiotics as a whole is preoccupied with meaning and communication as a cultural product and as a natural condition. The former has usually been associated to the study of cultural objects, representations, and artifacts, while the latter is more indicative of concerns regarding perception, language, and communicative processes.

Biosemiotics, as a branch of semiotics, attempts to provide a semiotics of the natural world and its organisms, considering their full range of subjectivity (Kull et al. 2011) while also trying to naturalize semiotic theories (Queiroz et al. 2011). Here, semiotic theory is seen as capable of informing biology, providing a picture of what mechanistic views on life are missing (Hoffmeyer 2011) and giving a scientifically valid perspective on the subjectivity of all organisms. Peirce’s ideas are essential to a large amount of the biosemiotic literature and a cornerstone of modern semiotics (Romanini and Fernández 2014).

Historical Perspective

When introducing Peirce’s semiotic theory, there are two historically relevant figures that are pivotal in the discussion of his place in semiotics: Kant and Frege. We will start with the latter. Logic was one of the axes on which Peirce centered his exploration of philosophical topics, and it is in this area that both Peirce and Frege intersect. First let’s examine some central notions of Frege’s own work in order to contrast them with some of the most relevant Peircean concepts for semioticians.

Frege and Semantic Value

Frege, much like Peirce, was an anti-psychologist about logic (Potter 2010). This meant that he was convinced that there is something about the world that does not necessitate mental powers in order to bring about the laws of logic. Though Frege’s great contributions to logic are far beyond the aim of this article, it’s important to note that the convergences between Frege and Peirce are criticalFootnote 2 in that they give us a more robust sense of what is at stake when semantics are involved. To that is added the overlap in their thoughts about logic and notation, driving forward a formalized and architectonic vision of theoretical commitments and outcomes.

One of the most famous and relevant distinctions that Frege makes for semantics is that of Sinn and Bedeutung, introduced as such in the last decade of the 19th century, and usually translated as “sense” and “reference.” While the distinction itself is intuitive, the concern behind it was rather of a formal nature: that an object has multiple ways of being accounted for resulting in different possible inferences from its presentation, and that “an appeal to the difference between the signs does not explain the difference in content” (Potter 2010, p. 13). This plays out in Frege’s anti-psychologism by a sense of truth values, where expressions are true not by virtue of our perception, but as an independent fact of the world, a true sentence being one that refers to an actuality in it.

At the basis of the issue, Sinn refers to the mode of presentation of the reference, while the Bedeutung of an expression would be what it represents (Recanati 2008, p. 31). David Bowie and Ziggy Stardust both refer to or denote David Robert Jones. Both expressions have, however, different senses in that they are presented in different ways.

It is interesting to ask ourselves whether biosemiotics, as an offshoot of semiotics, would be possible under a Fregean framework. A hint here can be seen in Barbieri’s brief inclusion of “sense” and “reference” in his Code Biology framework, a related discipline where meaning is deemed central to biology. Here, Barbieri assumes two types of semioses as axiomatic,Footnote 3 “one based on coding and the other on interpretation” (Barbieri 2015, p. 164), which can be mapped on Sinn and Bedeutung as meaning can obtain inside or outside of a semiotic system. The simplification of the difference points to a couple of things: that the application of a purely Fregean terminology to biosemiotics would require an extensive elaboration of the terms as applied to nonlinguistic organisms, much more than Barbieri does in this case, and that treating linguistic meaning in the same sense as biological meaning can be a dangerous way of self-confirming a theory without the original theory doing the work required for the confirmation.

For now we must put these concepts aside and move on to a different area of relevance. We will now see what Kant has to offer in relation to Peirce’s work and influence on biosemiotics.

Kant and the Categories

If Frege is a contiguous force to Peirce, Kant is a figure that precedes them both. Peirce’s work on his categories may be one of the most relevant stepping stones in his semiotic system. And referring to them is not possible without first mentioning Kant’s influence in this point (Pietarinen 2015, p. 373). Categories are generally conceived as sets of kinds, the types of things there are in the world. But how can we verify that the categories we postulate are actual? To answer that, Kant shifts the question so as to ask what are the things that are given when cognizing anything. These are the a priori, basic concepts that are needed for perception and reference. Following Aristotle, Kant considers four different groups for his categories, quantity, quality, relation, and modality (Kant 1998, A70/B95), each containing three categories for a total of twelve different categories. While the specificity of these is not too relevant for our purposes right now, it is important to note what they do for us in general. They give us a list of possible relations from which we can draw regarding what we can say about the world. That is, all categories relate to our judgments in that they are the basal cognitive markers that we have for even thinking about things. This complex system is built from logic (much like the Peircean categories, as we will see), developed from the way judgments appear to refer to things. And as such, they govern all possible judgments we can make about anything, including judgments such as “Peirce is a biosemiotician” or “biosemiotics is Peircean.”

But what is the takeaway of this for biosemiotics? Kant’s influence on biosemiotics is extremely powerful, if rather silent. Jakob von Uexküll, one of the forefathers of biosemiotics, was a reader of Kant and some of his most important ideas are connected to his philosophical upbringing. Could we have a Kantian biosemiotics without Peirce? While this is most likely possible, it would seem that we would be missing much of the reason for having a conceptual apparatus proper to sign relations. Kantian categories do enough initial work to make us wonder if the metaphysics of categorial judgments are correct and work our way through them as applied to thoughts in nonlinguistic organisms (raising the question of what counts as thought in this particular framework). This, however, is not enough by itself to be of foundational relevance to biosemiotics.

Peirce, Reference, and Categories

Let’s go back to the concept of reference. Frege’s distinction between sense and reference is of enormous relevance in understanding how some identity claims are less trivial than we would expect. But what does that have to do with Peirce? For one thing, Peirce coins a rather different sense through which we can deal with identity relations. But instead of dealing with these technicalities, let’s see what Peirce’s sign terminology can say that is different from Frege’s own distinction.

Peirce’s work on his sign theory didn’t happen quickly. It evolved with his thought, and his early theoretical musings are often at odds with his later theory. What is taken to be limited to thought and language when dealing with sense and reference is extended in understanding the role of indexicals for a theory of signs (Short 2004). The indexical sign makes cognition not necessarily preceded solely by cognition: it allows the picking out of elements by virtue of the connection between the object and its index. But the index is more than a conceptual connection, its own nature is causal or nonceptual. Smoke, sound, fever, thunder, these are all comprised by the treatment of the index. Peircean signs extend the field of view beyond matters of language towards the nonhuman.

What about Kantian categories? Peirce develops a system of categories in response to Kant’s own thought, simplifying the twelve categories into three, Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness, each covering “quality, reaction and representation” (Pietarinen 2015, p. 373). The concepts behind Peircean categories do not imply the universality of judgments we see in Kant. In fact, Peirce states that,

For Aristotle, for Kant, and for Hegel, a category is an element of phenomena of the first rank of generality [...]. The business of phenomenology is to draw up a catalogue of categories and prove its sufficiency and freedom from redundancies, to make out the characteristics of each category, and to show the relations of each to the others. (Peirce 1931–1935, 1958, CP 5.43)

This differentiation Peirce makes between Kant and himself is at the origin of his own commitments: he condemns the view that the phenomenal is disconnected from the thing in itself (Pietarinen 2015, p. 373).Footnote 4 Yet Peirce’s categorical thought has a very specific derivation: categories are considered modes of being, and this will expand each of the three categories so that we can use the terminology in semiotics in a different way than we would if we only counted with Kantian categories.

History Matters

One important point to take away from this historical overview and comparison is that semiotics is not independent of other explorations in knowledge. Peirce is as much a product of his age as he is a response to previous philosophers. But the conceptual apparatus he developed is fruitful in ways that we will explore in what follows. Peirce’s theory of signs and philosophical backing in the categories are two of the essential components of a robust semiotics centered around his perspective. Biosemiotics is in a special position because it seems to stand at a crossroads between the scientific and the philosophic, but this is as much an innovation as it is a product of a specific, expanding intellectual history. In what remains we will explore Peirce’s contributions to current biosemiotics and some of the prospects for exploring his concepts and philosophy within the field.

Biosemiotics with Peirce

While the father of biosemiotics is traditionally considered to be Jakob von Uexküll (and for good reason), the current standing of the field owes Peirce just as much, particularly in the developments that followed Sebeok’s own usage of Peirce (Jappy 2023). The construction of a modern biosemiotics takes as much from the turn in general semiotics as it does from biology, but in order to reach biosemiotics with Peirce, we had to count with a top-down approach, that is, starting from the traditionalist position of linguistics and working our way towards ethology.

Current biosemiotics works under a strong Peircean framework (Kull et al. 2009; Anderson et al. 2010; Barbieri 2015), and that is because sign theory does a lot of work in reframing how we understand biological organisms and their action in their environments. But it is far more than that. The philosophical foundation given by sign theory is an expanding and complex one, one that cannot be decided by dogmatism alone.

Let’s examine, for instance, how Anderson et al. (1984) incorporate Peirce in the crucial 1984 manifesto “A Semiotic Perspective on the Sciences”: they start by assuming that the universe, as stated by Peirce, is “perfused with signs” (1984, p. 8) in that they

suggest, nodding to Peirce, that the universe originated with the sign. This thirdness would have to presuppose secondness, and in turn firstness. The evolution from free energy-information, interaction, communication, meaning, and condensed meaning stored in knowledge systems can be all understood as further by-products in the ontogeny of the universe-system.

Here we can start tracing part of the value given to Peircean metaphysics by biosemiotics in its original, more formal expressions. Construing our subject matter as expanding from the kernel of signs can provoke all sorts of reactions from us now, but it serves an important purpose: that of having a ground on which to stand when referring to sign action in things we would not refer to as having the property of cognition. We also start seeing how the Peircean concepts we have just seen do play an important role in semiotic theory. These do not simply refer to phenomena we are accustomed to (such as street signs or words), but rather conceptualize things we need to know in order to refer to semiosis in living, nonlinguistic beings. Let’s examine some semiotic terminology more closely now.

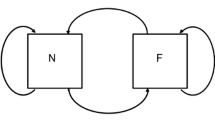

The Sign Relation

The sign relation is perhaps the central notion of general semiotics. This seems to make sense, given that we use “signs” as placeholders for “referring to something by means of something else.” Now, a sign in Peirce’s view is a triadic relation between an object, a representamen, and an interpretant.Footnote 5 This is important because it furnishes us with the technology to analyze sign action by its different components, to the degree that we can apply this formulation to understand behavior even when reportability is out of the question. While this is not enough to understand the subjectivity of organisms, it can lead us to an understanding of a meaningful relation between, say, a lion observing its careless prey band then flanking it. The sign relation is the essential building block for semiotics in that we give consistency to our understanding of meaning. That is, meaning for biosemiotics does not require the fixation of a concept or belief by means of having a previous reference. Instead, a sign relation is entailed by perceiving something and reacting to that perception. The interpretant in our example does not need to be “my prey is distracted,” but rather it can be the act of attacking itself.

A couple of examples, following Claus Emmeche, go like this:

The shrieking sound of a vervet monkey can be a representamen of a snake determining another monkey to hide in a tree, the act of hiding being the dynamic interpretant of the sign. A sequence of nucleic acid nucleotides sometimes functions as a genetic sign for a specific array of amino acids, resulting in an “object”, i.e., a protein, produced in a specific context. (Emmeche 1991, p. 326)

This very basic triad can have all sorts of applicability when dealing with potentially significative phenomena. But it is fair to ask ourselves if this application may be rather far-fetched, for what stops us from applying the sign relation to any potentially unrelated set of elements? Though this is an ongoing debate,Footnote 6 we need to limit the way we can apply relations. After all, the definition Peirce gives implies that a triadic relation is necessarily irreducible. This we translate informally into the idea that the elements of the sign relation must be implicated in the act of interpretation (Peirce 1931–1935, 1958, CP 1.345). In other words, you can’t have an interpretant of any sort without also having a representamen and an object. However, these concepts are not to be mapped to physical instances by necessity; they are abstractions of acts of cognition sensu lato.

The question that remains here is how the relation is entailed. But this is not a question we will be able to solve in this space. In fact, it is a question that can and will play a significant role in the philosophical discussions within biosemiotics.

Interpretation and Instantiation

One keyword we only mentioned in passing before is that of interpretation (which is not the same as an interpretant). In order to reach this idea, let us consider Peirce’s basic classification of signs into icons, indices, and symbols, all of which are built upon the basis of the sign relation. Briefly, an icon is a relation of resemblance, an index is a relation of causality, and a symbol is a relation of convention. This is but the tip of the iceberg of sign classifications, but it will have to do for the time being.Footnote 7 What is important to point out is that these types of relations require a number of things. An index requires an apparently causal connection between the object and the representamen–but this is not sufficient to have a sign! The representamen is not conditioned to one specific “answer,” but it is an “answer” nevertheless. The causal relation is a relationship of causalities so perceived by some organism that generates an interpretant. So if you see smoke behind the trees where your car is parked, this may act as an indexical of your exploding car. What the relation requires in actuality is the possibility of being interpreted. Peirce assigns a value of mind to reality that goes far beyond the concept of the human mind for interpretation, and this has been construed in different ways, namely:

-

panpsychism (the idea that everything possesses mental properties);

-

physiosemiosis (the idea that semiosis is entailed by physical systems);

-

pansemiosis (the idea that everything is composed of signs);

-

the more moderate view of biosemiotics, which simply entails that sign action is effective in the biological world.

A problem faced by biosemiotics is that the concepts used by the field both propose a theory and become their own explanation. The way to deal with this, however, is by appealing to a parallel notion: that life and semiosis are coextensive, and the basic operative semiosic organism is the cell (Emmeche et al. 2002). All questions regarding the standing of life must be investigated properly, but they are not easy to answer. We make this question clearer by asking about semiotic thresholds and assuming the threshold between the semiotic and the non-semiotic at the level of the cell (though cases could be argued at the level of viruses, for instance). A Peircean interpretation allows us at least to make a stronger case for the instantiation of signs in living systems, coupled with ethology and chemistry. This still leaves many questions open: Can there be symbols in the world of a cell? Is metabolism a semiotic process of interpretation? These and many others are questions that biosemiotics cares about.

There is still much more to understand about this basic classification of signs. Perhaps a good way to tackle this is by going straight to the categories. As we may remember, the categories for Peirce refer to modes of being, that is, they cover phenomena in the world in their most basic expression. These categories, phenomenological as they present to ourselves,Footnote 8 are relevant to sign research in that, being the possibilities in perception, they reveal to Peirce the specific condition of signs:

On the basis of this categoreally animated investigation, he was led to three classifications: that of signs in themselves being qualisigns, sinsigns, and legisigns; that of signs in relationship to their objects being iconic, indexical, and symbolic; and that of signs in relationship to their interpretants being rhematic, dicent, or suasive. (Colapietro 2008, p. 44)

While the categories appear to be related to knowledge and not to being since they allow us to find and analyze signs, there’s an important part uniting both conceptions, and that is Peirce’s idea of continuity or synechism. He sees mind and matter in continuity as a way to avoid strong dualisms, and thus the categories are both part of the description of the mental and the physical. Despite the fact that the categories seem to be ontological in nature, they are derived from phenomenology, and this can be granted because Peirce attempts to naturalize the mental to a certain degree.

Synechism and Tychism

Synechism is an ontological principle of its own,Footnote 9 and it is the underlying proposition for the existence of the categories. However, much like the sign relation, its extension can be rather dangerous for our theories. We will examine these dangers later, but for now we must resist extending concepts under the assumption that a theory needs to mark its territory so as to be applicable to something rather than to everything (for if it’s applied to everything, it’s useless). With that in mind, let’s assume thus that synechism acts as the principle that:

-

allows the existence of categories from its ontology,

-

connects the perceiver to the world,

-

naturalizes sign relations.

All of these points are essential for semiotics. And the principle of naturalization is perhaps the chief driver of biosemiotic enquiry. When examining the principle of synechism as related to the infinite possibility of signs, we find that Peirce’s thought is evolutionary. Peirce is a firm believer in what he calls tychism, the idea of “absolute chance” (Peirce 1931–1935, 1958, CP 6.102). This, for him, means that the universe must be evolutionary by necessity, with mental properties being a natural part of the growth of the universe. Peirce made efforts to transcend dualism, so he thought that an evolutionary approach would turn the tables against the idea of the mental and the physical being distinctly separated (as in substance dualism) (Calcaterra 2011). Naturalization thus opens the door to the examination of sign action in all living systems, at least metaphysically speaking. The case Peirce makes for a developed semiotics gives the examination of semiosis as part of the living a strong background, but much like signs, we need interpretation in order to make our theories of biosemiotics work.

Categories

We have already introduced the concept of categories by way of Kant. Now, however, we can address them in the more specific Peircean sense. The categories are considered by Peirce to be modes of being, which we could understand as properties of things related to their complexity (and perhaps even to what we can say about them). Peircean categories, while not being exclusive of potential extensions, are minimally speaking three—Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness—each with a specific constitution and enabled by synechism. Though these three categories have been also called Quality, Reaction, and Representation, or Possibility, Actuality, and Reality (Stjernfelt 2007, p. 13), we can examine them further and attempt to give them a more precise definition.

The premise of a continuum in reality can be acknowledged, for Peirce, within a phenomenal analysis. As such, Peirce recognizes that there are three categories to experience that can be elucidated and formalized.

Firstness

Firstness is a quality or possibility that Peirce recognizes, according to Stjernfelt, as the

quality of experience: in order for something to appear at all, it must do so due to a certain constellation of qualitative properties. Peirce often uses sensory qualities as examples, but it is important for the understanding of his thought that the examples may refer to phenomena very far from our standard conception of ‘sensory data’, e.g. forms or the ‘feeling’ of a whole melody or of a whole mathematical proof, not to be taken in a subjective sense but as a concept for the continuity of melody or proof as a whole, apart from the analytical steps and sequences in which it may be, subsequently, subdivided. (Stjernfelt 2007, p. 13)

As an example, Peirce uses the notion of redness as a sui generis quality (Peirce 1931–1935, 1958, CP 1.25). With this we start seeing how Peircean semiotics establishes a type of theory of perception with its own specific terminology.

Secondness

Firstness appears to be the simplest element we can find in our phenomenal experience, but it is only analyzable through a more complex set of experiences, so to speak. However, its individuality doesn’t do anything for us. Secondness (reaction or actuality) bridges Firstness by making qualities patent. Houser sees Secondness as “that which is as it is in relation to something else” (Houser and Cobley 2010, p. 90). To expand on this, we can take this example from Peirce:

Standing on the outside of a door that is slightly ajar, you put your hand upon the knob to open and enter it. You experience an unseen, silent resistance. You put your shoulder against the door and, gathering your forces, put forth a tremendous effort. Effort supposes resistance. Where there is no effort there is no resistance, where there is no resistance there is no effort either in this world or any of the worlds of possibility (Peirce 1931–1935, 1958, CP 1.320).

The example may seem contrived at first glance, but the idea is that Secondness is the expression that puts quality into matter (Peirce 1931–1935, 1958, CP 1.527). As Pietarinen puts it in a more poetic fashion, Secondness implies “the struggle to achieve something, the shock of sensing change” 2015, p. 374.

Thirdness

Thirdness (representation, reality) subsumes the previous categories into a more complex one. The keyword for Thirdness is mediation (Peirce 1931–1935, 1958, CP 1.328). Peirce himself specifies that by Thirdness, he means “the medium or connecting bond between the absolute first and last” (Peirce 1931–1935, 1958, CP 1.337) in that the elements in a perceptual instance become patent, both in their quality and the imprint of said quality in something different from the quality itself. But this is not only limited to perceptual instances, it is reflected in many metaphysical theses, such as how natural laws are derivations of Thirdness itself.

The categories as presented by Peirce start then by being a phenomenological exploration with important metaphysical implications, but also depending on certain other propositions in order to work, such as synechism.

The complexity of Peirce’s thought allows, as a result, a number of potential interpretations (as we saw above). There is a certain vagueness that allows us to speak much more about the things we have already mentioned, but at the same time many of these can be easily taken to mean far more than we could desire for our semiotic theories. In what follows we will take a quick look into some of the possibilities a Peircean framework offers for different perspectives in biosemiotics.

Biosemiotics Through Peirce

We have set some of the fundamental building blocks for talking about a potential semiotic biology based on Peirce’s work on phenomenology and metaphysics. This task is, as we may have noticed, intrinsically philosophical, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be applied to the analysis of biological phenomena. Let’s now see how Peirce has been used by different biosemiotic accounts and what his place is in current biosemiotics.

Hoffmeyer’s Peirce

Jesper Hoffmeyer, one of the key figures in the development of current biosemiotics, makes ample use of Peircean terminology throughout his work. He introduces the basic sign concept as described by Peirce (Hoffmeyer 2008, pp. 20–21), trying to move it away from any sense of exclusive applicability to human interpreters. One specific example he gives starts with a triad involving a slap that causes a deformation over the skin’s sensory cells:

With the application of pressure, there emerges an interpretant in the form of a context-dependent sequence of action potentials that create a kind of cellular echo of the disturbance. This interpretant, the echo, now becomes part of a more complex sign [...]. There, the pattern of action potentials from many different sources, tactile as well as kinesthetic, is processed under the formation of a stereognostic codification of the experience of pressure. (Hoffmeyer 2008, p. 23)

Right off the bat we have an application of the sign as a sort of reaction model applied over cellular mechanisms, from the transduction of a physical disturbance to a particular perception of touch. This at first reads like a theory of perception involving a different type of description, but to this Hoffmeyer responds stating that a chemical description is not quite enough, with biosemiotics offering a union of the psychophysical “for free” (Hoffmeyer 2008, p. 24). How so? Because of the categories. For Hoffmeyer, causality becomes an essential topic, making use of Aristotelian causes as part of his ontology. To him, causality “follows from the recognition that actions or processes can either play out within relations of Secondness or within relations of Thirdness (but not, however, within relations of Firstness [...])” (Hoffmeyer 2008, p. 67). The categories create, in Hoffemeyer’s biosemiotics, a basal constituent of reality, and causal processes that we can identify through science appear at the level of Thirdness.

Cybersemiotics and Biosemiotics

From a different perspective, we have another heavily Peircean approach in what has been called cybersemiotics, a distinct (yet related) take on biosemiotics with different methodological aims and practical objectives. For Brier,

Peircean biosemiotics is based on Peirce’s theory of mind as a basic part of reality, (in Firstness) existing in the material aspect of reality, (in Secondness) as the “inner aspect of matter” (hylozoism) manifesting itself as awareness and experience in animals, and finally as consciousness in humans. (Brier 2008, p. 40)

The evolutionary aspect of Peircean thought becomes all the more relevant here as the theory implies a specific direction of evolution towards more complex consciousness. An important point in Brier’s interpretation rests in the idea that intentionality is not necessary for sign action, for Peircean semiotics covers unintentional cognitive phenomena, as opposed to a direct symbol grounding that only relates to the intentionality of sign usage. Interestingly, Brier opposes Frege and Peirce, albeit subtly, when he states that an approach that justifies beliefs as mapped to truth values starts on the logical side in order to describe mental processes, situating Peirce on abductive reasoning, seeing

the development of knowledge as a dynamic relation between belief, doubt, desire, and inquiry, and the self-correcting nature of semiosis. Beliefs are certain behavioral dispositions that manifest themselves in a given context based on certain desires. They may be changed through processes of inference, which change our representations of the world. Truth and reality, thus, to a certain extent, depend on the social construction of inquiry. But, on the other hand in his triadic evolutionary view, semiosis can be viewed as self-correcting in its reproduction of Thirdness. (Brier 2008, p. 42)

Brier’s Peirce has a different significance for the nature of scientific inquiry, because the nature of sign action can be applied to cognition sensu lato and to scientific practices.

Tartu Biosemiotics

Relevant figures in biosemiotics usually agree on core premises. Peircean signs are taken as primitives for the theory in general, but the specifics usually rest in how Peircean theory is seen, and to what extent it is assumed to be applicable. While there is nothing quite specific about how Tartu biosemiotics deals with Peircean philosophy (as most of it comes from the Copenhagen connection in the so-called Copenhagen-Tartu School of biosemiotics; Hoffmeyer and Kull 2011), there are certain theories set against the backdrop of Peircean terminology. Take, for instance, Kull’s proposal for a triadic layering of natural semiotic capabilities (Kull 2009). Here, the talk of semiotic zones or thresholds is coupled with a Peircean understanding of sign types, with the vegetative level being capable of recognition (icons); the animal level, of association (indexes); and the cultural level, of combination (symbols) (Kull 2009, p. 15). There is no denying the powerful influence of Peircean terminology in biosemiotics. The expansion and recombination of Peircean influences with the early cybernetic turn in Tartu-Moscow semiotics has been shown to be a fruitful interaction for the development of semiotic theory.

Yet Peirce is a very complex thinker, and much of his theory can and will be subject to scrutiny by different research programs. We will now take a look at some of the criticisms that have been raised against Peircean biosemiotics.

Assessing the Correctness of Peirce’s Claims for Biosemiotics

Even if all we have been able to cover so far is but a superficial level of Peirce’s philosophy of semiotics, the intricacy of his work should be apparent. The categories and the sign relation itself are interwoven and supported by a number of investigations that have impacted the way we talk about signs and reference, especially in the realm of ascribing sign action to nonlinguistic living beings. But Peirce’s theory is not without critics, and biosemiotics does not need to follow Peirce axiomatically to say something interesting about meaning in biology.

Perhaps the most vocal opposition against a Peircean framework for biosemiotics comes from Marcello Barbieri’s proposal for Code Biology. Code Biology, a parallel approach that has at times been related to biosemiotics, deals with the idea that organic codes are arbitrary (Barbieri 2019). Barbieri takes the Peircean framework to entail pansemiosis (Barbieri 2015, p. 156), so limiting its explanatory power is of the utmost importance. To this he adds the criticism that Peircean models cannot be taken as radical, but they must be empirically tested. This unfurls into a methodological criticism and a division between trends in biosemiotics: “one is the extension of Peirce’s model to all living creatures, the other is a scientific approach that aims at discovering which semiotic processes actually take place in living systems” (Barbieri 2015, p. 156). The culmination of this criticism appears in two points, that Peircean biosemiotics is nothing but a reformulation of previously known biological terms in order to fit Peirce’s own terminology; and that biosemiotics is possible only if we ditch ad hoc definitions and move to an experimental setting.

Another type of criticism that also comes from Barbieri is institutional in nature. Biosemiotics is predominantly Peircean, and with semiotics gaining intellectual traction, “the Peirce industry has grown into an impressive enterprise that, like the Darwin industry in biology, is producing a steady flow of books, journals, congresses, grants and University positions” (Barbieri 2015, p. 168).

Finally, perhaps one of the most worrying criticisms, is that

The scientists that were supporting the Peircean approach were often using the arguments employed by the supporters of Intelligent Design. In retrospect this is hardly surprising, because ‘interpretation’ is indeed a form of ‘intelligence’, and Peirce himself promoted the idea that there is an extended mind in the Universe. The difference between the two cases is that in Intelligent Design the ‘interpreting agency’ is outside Nature whereas in Peircean biosemiotics is inside it. The common factor is that in both cases all facts of science are reinterpreted in a postmodern framework simply by changing the meaning of words (Barbieri 2015, p. 168)

The jury is still out regarding these claims, but these are valid concerns for a semiotics building towards a naturalized framework.

In the theoretical arena, we can still debate the merits of Peircean theory for biosemiotics. Are signs simply a way to rename cybernetic cell processes? How do we even limit the Peircean framework in the face of its apparently explosive expansion? Vehkavaara says of biosemiotics that it can be taken “as a mere heuristic device, eliminable language-game, illustrative metaphor, or decorative topping for primary biological theory”; however, “biosemioticians hope it could bring up some new substantial theory or irreducible concept to biology” (Vehkavaara 2005, p. 270). He goes on to state that Peirce’s own view on signs rests more on an impressionistic view than on having verified scientific results about them (Vehkavaara 2005, p. 273). In addition to that, metaphysical claims about the sign in biosemiotics tend to be vague: “Quite commonly in biosemiotic literature, it is left unspecified (or the specification is clearly unjustified) what is the object or the interpretant of the considered sign and who (or what) is the ‘interpreter’ that executes the sign-transformation” (Vehkavaara 2005, p. 281). Besides this theoretical vagueness, biosemiotics may axiomatize metaphysical hypotheses and make overtly strong claims regarding the ontology of the sign.

These are all claims that can be examined through biosemiotics, but importantly they must play a role in how we understand Peirce as applied to current research. We can justifiably take issue with the philosophical underpinnings of biosemiotics, but in order to, for instance, criticize the possibility of icons in nature, we need to understand what the terms refer to and how we even got to the point where we can argue for icons as signs.

Peirce’s contribution does much work for semiotics, but a critical eye regarding the metaphysical claims that have been made to support our semiotic models, even outside of biosemiotics, are of the utmost importance, opening options to consider Peirce critically, but within a valid scope of applicability (Olteanu 2019).

The Overlap between Biosemiotics and the Philosophy of Biology

Biosemiotics seems unique in that it draws from multiple, unlikely sources to hopefully say something novel about biology. Though Peirce’s philosophy has indeed been presented philosophically as suitable for understanding some aspects of biology (Emmeche 1991), the overlap between the areas that biosemiotics covers and what philosophers of biology care about is yet to be mapped out, at least in the senses of biological theses, conceptual issues in biology, and naturalization of philosophical problems in biological terms, as outlined by Odenbaugh and Griffiths (2022). Hoffmeyer’s claim that biology is immature biosemiotics (Hoffmeyer 2009) makes an appeal to biologists to reconsider some foundational concepts, such as the centrality of subjectivity in biological explanations, enabled thus through Peircean philosophy. Biosemioticians often study issues related to evolution (Andrade 2007; Sharov and Kull 2022; Rodríguez Higuera 2023), trying to discover causal relations between the subjectivity enabled by Peirce’s concept of the sign and the way we look at evolution.

In line with the Darwinian concerns of the philosophy of biology (Rosenberg and McShea 2008, p. 7), biosemioticians are interested in testing the philosophical claims made by different varieties of evolutionary theory, under the premise that semiotics does have an impact in how we look at organisms (Noble 2021). Peircean philosophy, when read metaphysically, can find large intersecting paths with the metaphysics of biology—a naturalistic stance about metaphysics, assigning primacy to biological claims (Dupré 2021)—making claims about emergence (van Hateren 2015), causation (Nomura et al. 2019), and so on.

Semioticians may also be interested in naturalizing philosophical claims made by Peirce to fit in a more experimentally oriented setting within biosemiotics (Kilstrup 2015), and ask metatheoretical questions about the status of a naturalized biosemiotics (Brier 2015). Peircean biosemiotics is, by its own construction, a philosophical task, though its lack of overlap with more traditional philosophical avenues makes semiotic claims sometimes harder to examine from outside the consensual perspectives developed by biosemioticians.

Historians of semiotics have, in recent years, reclaimed large swathes of philosophical writing as part of the semiotic heritage (Deely 2001; Favareau 2015), and in accepting this philosophical background we see that what sets biosemiotics apart from the philosophy of biology is a matter of focus, not of origins, making it possible to argue for biosemiotics as an overlooked and specific area of research belonging to the wider family of the philosophy of biology altogether.

Charles Peirce’s philosophy is an integral piece in clarifying and developing the positions usually supported by biosemioticians, and by having a clearer picture of the role of his philosophy of signs with regard to biology, at least from the perspective of biosemiotics, more avenues of critique and cooperation can be opened for researchers interested in the place of subjectivity in biology, understood as the faculty of organisms of using signs in their Peircean description (Kull 2023). The promise of the biosemiotic approach lies in providing a robust sense of subjectivity that can be describable and, when coupled with Uexküllian approaches, made sense of as a set of significant relations for organisms (Augustyn 2009), that will in turn provide a descriptive and analytical language to treat ontological claims about living systems, their world of perception, and how this influences behavior and evolution.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

“Subjectivity” as a philosophical problem, particularly when applied to nonlinguistic organisms, may hinge on a kind of underlying dualism (Sonnenhauser 2010) that biosemiotics, through Peirce, attempts to overcome by using signs as part of the whole sphere of general cognition.

While it seems that Peirce and Frege were not aware of each other’s work, there is some soft evidence for a tenuous connection between the two of them in terms of access to their scholarship (Hawkins 1993).

Semiosis is usually considered to be something akin to the “action” of signs. Barbieri states that, “The origin of molecular copying and the origin of molecular coding produced [...] the first two types of semiosis” (Barbieri 2015, p. 33), one “based on coding and one based on interpretation” (Barbieri 2015, p. 150). This requires much more unpacking and goes beyond the purpose of this article.

It is important to note that, “As Kant insisted – and, of course, both Peirce and Jakob von Uexküll had thoroughly assimilated Kantian principles – ‘raw experience’ is unattainable; experience, to be apprehended, must first be steeped in, strained through, and seasoned by a soup of signs” (Sebeok 2001, pp. 36–37).

We will refer to the terms of the sign relation with these concepts throughout the article, but it is important to remember that each has been named something different at certain points. It’s also quite important to remark that the representamen has also been called sign but we will do our best to avoid any confusion in this matter. An important analysis of how this may be a biosemiotic development beyond Peirce can be found in Jappy (2023, pp. 2–5).

For a detailed discussion on the possibilities that extend from here, see Borges (2010)

Or phaneroscopic in Peircean parlance.

Peirce, though, regarded it as a “regulative principle of logic” (Peirce 1931–1935, 1958, CP 6.173).

References

Anderson M, Deely J, Krampen M, Ransdell J, Sebeok TA, von Uexküll T (1984) A semiotic perspective on the sciences: steps toward a new paradigm. Semiotica 52(1–2):7–47. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1984.52.1-2.7

Anderson M, Deely JN, Krampen M, Ransdell J, Sebeok TA, von Uexküll T (2010) A semiotic perspective on the sciences: steps toward a new paradigm. In: Favareau DF (ed) Essential readings in biosemiotics. Anthology and commentary. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 377–413

Andrade E (2007) A semiotic framework for evolutionary and developmental biology. Biosystems 90(2):389–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystems.2006.10.003

Augustyn P (2009) Uexküll, Peirce, and other affinities between biosemiotics and biolinguistics. Biosemiotics 2(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12304-008-9028-y

Barbieri M (2015) Code biology: a new science of life. Springer, Cham

Barbieri M (2019) Code biology, Peircean biosemiotics, and Rosen’s relational biology. Biol Theory 14(1):21–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13752-018-0312-z

Borges P (2010) A visual model of Peirce’s 66 classes of signs unravels his late proposal of enlarging semiotic theory. In: Kacprzyk J, Magnani L, Carnielli W, Pizzi C (eds) Model-based reasoning in science and technology model-based reasoning in science and technology, vol 314. Springer, Berlin, pp 221–237

Brier S (2008) Cybersemiotics: why information is not enough! University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Brier S (2015) Can biosemiotics be a “science" if its purpose is to be a bridge between the natural, social and human sciences? Prog Biophys Mol Biol 119(3):576–587

Calcaterra RM (2011) Varieties of synechism: Peirce and James on mind-world continuity. J Specul Philos 25(4):412–424

Champagne M (2013) A necessary condition for proof of abiotic semiosis. Semiotica 2013(197):283–287

Cobley P (2010) Introduction. In: Cobley P (ed) The Routledge companion to semiotics. London, Routledge, pp 3–12

Colapietro V (2008) Peirce’s categories and sign studies. In: Petrilli S (ed) Approaches to communication: trends in global communication studies. Atwood Publishing, Madison

Deely JN (2001) Four ages of understanding: the first postmodern survey of philosophy from ancient times to the turn of the twenty-first century. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Deely JN (2006) On ‘semiotics’ as naming the doctrine of signs. Semiotica 2006(158):1–33

Dupré J (2021) The metaphysics of biology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Eco U (1976) A theory of semiotics. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

Emmeche C (1991) A semiotical reflection on biology, living signs and artificial life. Biol Philos 6(3):325–340

Emmeche C, Kull K, Stjernfelt F (2002) Reading Hoffmeyer, rethinking biology. Tartu University Press, Tartu

Favareau DF (2008) The evolutionary history of biosemiotics. In: Barbieri M (ed) Introduction to biosemiotics: the new biological synthesis. Dordrecht, Springer, pp 1–67

Favareau DF (2015) Why this now? The conceptual and historical rationale behind the development of biosemiotics. Green Lett 19(3):227–242

Hawkins BS (1993) Peirce and Frege, a question unanswered. Modern Logic 3(4):376–383

Hoffmeyer J (2008) Biosemiotics: an examination into the signs of life and the life of signs. University of Scranton Press, Scranton

Hoffmeyer J (2009) Biology is immature biosemiotics. Deely JN, Sbrocchi LG (eds), Semiotics 2008: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Meeting of the Semiotic Society of America. Legas, Ottawa, pp 927–942

Hoffmeyer J (2011) Biology is immature biosemiotics. In: Emmeche C, Kull K (eds) Towards a semiotic biology. Imperial College Press, London, pp 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1142/9781848166882_0003

Hoffmeyer J, Kull K (2011) Theories of signs and meaning: views from Copenhagen and Tartu. In: Emmeche C (ed) Towards a semiotic biology, vol 1. Imperial College Press, London, pp 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1142/9781848166882_fmatter

Houser N, Cobley P (2010) Peirce, phenomenology, and semiotics. The Routledge companion to semiotics. Routledge, Oxon

Jappy T (2023) Biosemiotics and Peirce. Lang Semiotic Studies. https://doi.org/10.1515/lass-2023-0011

Kant I (1998) Critique of pure reason. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kilstrup M (2015) Naturalizing semiotics: the triadic sign of Charles Sanders Peirce as a systems property. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 119(3):563–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2015.08.013

Kull K (2009) Vegetative, animal, and cultural semiosis: the semiotic threshold zones. Cognitive Semiotics 4:8–27

Kull K (2023) Necessary conditions for semiosis: a study of vegetative subjectivity, or phytosemiotics. In: Coca JR, Higuera CJR (eds) Approaches biosemiotics. Ediciones Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, pp 59–74

Kull K, Deacon T, Emmeche C, Stjernfelt F, Hoffmeyer J (2009) Theses on biosemiotics: prolegomena to a theoretical biology. Biol Theory 4(2):167–173

Kull K, Emmeche C, Hoffmeyer J (2011) Why biosemiotics? An introduction to our view on the biology of life itself. In: Emmeche C, Kull K (eds) Towards a semiotic biology. Imperial College Press, London, pp 1–21

Noble D (2021) The illusions of the modern synthesis. Biosemiotics 14(1):5–24

Nomura N, Matsuno K, Muranaka T, Tomita J (2019) How does time flow in living systems? Retrocausal scaffolding and e-series time. Biosemiotics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12304-019-09363-x

Odenbaugh J, Griffiths P (2022) Philosophy of biology. In: EN Zalta (ed) The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (summer 2022 edn). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/biology-philosophy/. Accessed 30 Oct 2022

Olteanu A (2019) Schematic enough to be safe from kidnappers: the semiotics of Charles Peirce as transitionalist pragmatism. J Philos Educ 53(4):788–806

Peirce CS (1931-1935, 1958) The collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Vol. I-VIII. Hartshorne C, Weiss P (eds). Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Pietarinen AV (2015) Signs systematically studied: invitation to Peirce’s theory. Sign Syst Stud 43(4):372–398

Potter M (2010) Introduction. In: Ricketts MPT (ed) The Cambridge companion to Frege. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–31

Queiroz J, Emmeche C, Kull K, El-Hani C (2011) The biosemiotic approach in biology: theoretical bases and applied models. In: Terzis G, Arp R (eds) Information and living systems. MIT Press, London, pp 91–130

Recanati F (2008) Philosophie du langage (et de l’esprit). Gallimard, Paris

Rodríguez Higuera CJ (2023) Biosemiotics and evolution. In: Coca JR, Higuera CJR (eds) Approaches to biosemiotics. Ediciones Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, pp 99–111

Romanini V, Fernández E (2014) Peirce and biosemiotics: a guess at the riddle of life. Springer, Dordrecht

Rosenberg A, McShea DW (2008) Philosophy of biology: a contemporary introduction. Routledge, New York

Sebeok TA (2001) Signs: an introduction to semiotics, 2nd edn. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Sharov AA, Kull K (2022) Evolution and semiosis. In: Pelkey J (ed) Bloomsbury semiotics: history and semiosis, vol 1. Bloomsbury, London, pp 149–168

Short TL (2004) The development of Peirce’s theory of signs. In: Misak C (ed) The Cambridge companion to Peirce. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 214–240

Sonnenhauser B (2010) ‘Subjectivity’ in philosophy and linguistics. In: Stalmaszczyk P (ed) Philosophy of language and linguistics, vol 1. Ontos, Heunsestamm, pp 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110330472.277

Stjernfelt F (2007) Diagrammatology: an investigation on the borderlines of phenomenology, ontology, and semiotics, vol 336. Springer, Dordrecht

van Hateren JH (2015) The natural emergence of (Bio)semiosic phenomena. Biosemiotics 8(3):403–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12304-015-9241-4

Vehkavaara T (2005) Limitations on applying Peircean semeiotic: biosemiotics as applied objective ethics and esthetics rather than semeiotic. J Biosemiotics 1(1):269–308

Zengiaro N (2022) From biosemiotics to physiosemiotics: towards a speculative semiotics of the inorganic world. Linguistic Front 5(3):37–48

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by targeted funding provided by the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports for specific research, granted in 2023 to Palacký University Olomouc (IGA_FF_2023_044).

Funding

Open access publishing supported by the National Technical Library in Prague. Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports for specific research, granted in 2023 to Palacký University Olomouc (IGA_FF_2023_044).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez Higuera, C. Charles Peirce’s Philosophy and the Intersection Between Biosemiotics and the Philosophy of Biology. Biol Theory 19, 94–104 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13752-023-00445-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13752-023-00445-1