Abstract

Purpose of Review

Obesity is an overwhelmingly common medical entity seen in the adult population. A growing body of research demonstrates that there is a significant relationship between child maltreatment and adult obesity.

Recent Findings

Emerging research demonstrates a potential dose–response relationship between various types of child abuse and adulthood BMI. Recent work also explores the potential role of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, and other hormonal mediators such as sex-hormone binding globulin and leptin. There are also studies that suggest factors such as depression and socioeconomic and environmental influences mediate this relationship. Comorbidities that have been reported include cardiovascular and metabolic disease, diabetes, and insulin resistance. Preliminary work also demonstrates potential gender and racial disparities in the effect of abuse on adulthood obesity.

Summary

In this narrative review, we summarize the existing work describing the different child maltreatment types (physical, sexual, emotional, verbal, and child neglect) and their relation to adult obesity, what is known about a potential dose-response relationship, potential mediators and pathophysiology, comorbidities, and preliminary work on gender and racial/ethnic disparities. We review the limited data on interventions that have been studied, and close with a discussion of implications and suggestions for clinicians who treat adult obesity, as well as potential future research directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity is an increasingly prevalent public health problem with significant medical, mental health sequelae and societal implications including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, premature death, and an estimated economic health care burden of $172.74 billion annually [1]. The initial landmark study on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) introduced the concept of the relationship between childhood trauma and obesity, exploring ACEs and their association with high-risk behaviors and diseases with life-limiting consequences including as obesity, heart disease, cancer [2]. Accordingly, current medical evidence suggests that obesity as a medical condition is best understood as a multifactorial condition, with dynamics between genetics, health behaviors, environmental conditions, and exposures such as childhood maltreatment, trauma, and ACEs [3]. A breadth of medical literature has further explored the implications of toxic childhood stress and the specific association between childhood maltreatment and elevated body mass index (BMI) and obesity. This narrative review summarizes specifically what is known about the types of child maltreatment that have been implicated, timing and the dose–response relationship, neurobiology, mediators, comorbid outcomes, and emerging research on disparities and interventions.

Child Maltreatment Types

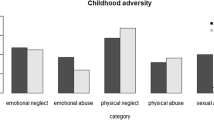

Child maltreatment, inclusive of physical and sexual abuse, psychological and verbal abuse, and child neglect have been described in association with obesity. This has been noted by several large cross-sectional surveys of adults with obesity [4,5,6,7,8]. Relative rates of maltreatment type vary by cohort. A meta-analysis conducted by Hemmingson and colleagues confirmed that multiple types of abuse (including physical, psychological, sexual) are all significantly associated with adult obesity, with no difference found between retrospective and prospective study designs [9].

While literature elucidating potential differences in effects by maltreatment type is limited, multiple studies suggest nonuniformity, and the conclusions vary widely by sample and study type. Several studies suggest child sexual abuse (CSA) is associated with adulthood obesity while not finding the same association with physical abuse. In a large representative U.S. cross-sectional sample, Fuemmeler and colleagues found an association between CSA and obesity in men, but not in women [10]. Similarly, another large study found CSA and child emotional abuse associated with increased BMI in women but did not find the same association for other abuse types and among men [11].

Conversely, a prospective cohort study where children with substantiated physical abuse, CSA, and neglect were followed into adulthood 30 years later, physical abuse was found to be a significant predictor of increased adult BMI scores while sexual abuse and neglect were not [12]. A systematic review evaluating interpersonal violence in childhood as a risk factor for obesity also found consistent associations in the majority of studies between physical abuse and obesity, though sexual abuse was also noted, and neglect and emotional abuse was not explored [13].

Some studies have also suggested that childhood emotional abuse or neglect rather than physical or sexual abuse are significantly associated with adult obesity. One longitudinal study found emotional abuse and neglect to be risk factors for obesity [14]. Mason et al. also found this in their cohort, noting emotional abuse to have the strongest association with BMI with no association noted for sexual or physical abuse [15].

Timing and Dose–Response Relationship

Current research explores the patterns of obesity development over the lifespan of children who experience maltreatment. Several studies suggest that obesity emerges early in adulthood. A prospective cohort found that women with histories of child abuse had higher BMI’s in early adulthood, and a large cross-sectional study found overall significantly lower age of onset of adulthood obesity in victims of childhood abuse [4, 11, 16, 17]. Furthermore, higher rates of BMI increase over time have also been described [16, 18].

A few studies have also found a dose–response relationship between childhood abuse and obesity. Two studies have found that victims of the co-occurrence of physical and sexual abuse demonstrate a stronger association with obesity risk, while another longitudinal cohort found that more severe abuse correlated with a higher obesity risk [15, 16, 19].

Neurobiology

Several neurobiological mechanisms have been studied as potential mediators. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is the most studied. The HPA axis is the primary neuroendocrine mediator for stress-responses and has been studied in multiple abused, neglected, and trauma-exposed populations [3]. The role of cortisol has been evaluated in several studies specifically looking at child maltreatment and obesity. One such study tested hair cortisol and cortisone levels and found that higher levels of abuse was associated with higher cortisone levels, suggestive of chronic stress levels. However, a mediating effect was not found for cortisol or cortisone between childhood maltreatment and BMI [20]. In two additional studies, cortisol response was tested via salivary testing and was found to be blunted in girls and women who had been sexually abused [21, 22]. Furthermore, poly-victimization was linked to lower cortisol response and higher BMI [21].

Other potential biological mediators include sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG), which has previously been implicated in mediating central adiposity in women [23]. One study demonstrated lower SHBG levels in women with a history of childhood trauma [13]. Leptin and inflammatory mediators have also been suggested, with a study by Danese and colleagues measuring leptin, BMI and c-reactive protein in maltreated children. Leptin provides negative feedback to downregulate adiposity by decreasing energy intake and increasing energy expenditure. They found that maltreated children had lower leptin levels with increasing inflammation and BMI [24].

Mental Health and Environmental Mediators

Childhood maltreatment has many sequelae, some of which are mediators of the effect on adult obesity. Mental health outcomes are often inter-related. Multiple studies have demonstrated depression as a mediating factor, especially in females [25,26,27,28]. Anxiety has also been described, specifically in women in one study [29, 30]. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has also been widely described as a result of childhood maltreatment, though notably has not consistently been demonstrated as a mediator [31, 32].

Certain eating disorders also have an expected causal link with obesity, and studies indicate that it may also function as a mediator of the child maltreatment effect. Some studies link physical abuse and disordered eating including coping-motivated eating as mediators of obesity [10, 17]. On the other hand, emotional neglect and abuse have also been demonstrated to increase eating disorders, including night eating and binge eating syndromes [33, 34]. Substantiated child maltreatment in general has also been found to be associated with high dietary fat intake, food addiction, and binge eating [35, 36]. Preliminary work has also queried the impact of child maltreatment on impulsivity and has been found to moderate sexual abuse and obesity [37].

Socioeconomic and environmental factors are well established risk factors for obesity. Whether they function as mediators of the effect between child maltreatment and obesity is less clear, though a large survey study found that 15–20% of the association between ACEs and adult health risks (including obesity) could be attributable to socioeconomic factors [38]. Another large cross-sectional study found that childhood maltreatment was associated with adulthood obesity (as measured by weight-to-height ratio) but the socioeconomic factors mitigated the association in women but not in men [39].

Comorbid Outcomes

One of the measured comorbid outcomes of childhood ACEs in general includes cardiovascular and metabolic disease [2, 40]. Similarly, victims of childhood maltreatment suffer not only from increased obesity, but also cardiometabolic comorbidities. Abuse has been associated with adulthood diabetes and insulin resistance [4, 41]. Hyperlipidemia and lower HDL levels have also been reported [4, 14, 42].

Disparities

Data exploring gender disparities are limited and is even more sparse with regards to racial disparities. Nonetheless, preliminary work suggests potential differences, though trends are not well established. Several studies suggest that the association between CSA and BMI is present in females but not males [18, 43, 44]. Neglect and physical abuse have been described to demonstrate a stronger effect on BMI in females compared to males, and emotional abuse has shown a similar pattern [25, 43]. One study has reported the opposite effect, finding that CSA in males was associated with increased obesity compared with females [10]. In contrast, other studies have also found no gender difference [9, 45].

With regards to race, very few studies have evaluated potential disparities. One analysis of a large, longitudinal survey study found no race or ethnicity effect on the association between childhood physical abuse and obesity [45]. Another cross-sectional study conversely did find a difference, demonstrating a statistical relationship between child maltreatment and obesity in Whites but not in Blacks [46]. In a study with large proportions of Asian, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander representation, no race/ethnicity effect was found [47]. There are additional studies where samples consist primarily of one or a few particular races or ethnicities, but do not offer comparisons.

Interventions

Research on secondary prevention interventions targeting the effect of child maltreatment on obesity is sparse. Tavernier and colleagues studied a behavioral weight-loss intervention and found that physical abuse predicted a percent lower weight loss compared to emotional abuse or no abuse history [48]. Another study explored the role of mentorship in promoting resilience in child maltreatment survivors and found that mentorship was associated with decreased depression symptoms, but also conversely increased obesity [49]. While tertiary and primary interventions for obesity have been widely studied, the potential role of child maltreatment-targeted interventions remains poorly understood.

Conclusions

The body of research demonstrating a relationship between child maltreatment and obesity in adulthood is relatively recent. However, it is continuing to grow and holds significance for the myriad of types of clinicians who care for adults with obesity. While the exact physiology and ecological influences for this relationship are not yet fully understood, the data is robust enough that we suggest that clinicians caring for adult patients with overweight and obesity specifically query about histories of child abuse and neglect in a trauma-sensitive manner. For example, asking if the patient has ever been to therapy or struggled with mental health or substance use may open the door to further conversation about why. Clinicians may also consider asking a direct, but sensitively worded question about whether there are any life stressors that relate to their childhood, or even consider asking the patient themselves if there was any childhood trauma such as abuse that they perceive to relate to their current struggle with obesity. Clinicians should also consider when referrals or even clinic integration with mental/behavioral health colleagues may provide the holistic care needed to address the multifactorial issue of adult obesity.

Future work should explore in-depth the physiology and socio-ecological mechanisms for these trends, as this understanding may hold implications not only for current management but also potential primary prevention efforts that could be directed towards children who experience child maltreatment. There is also a paucity of literature on whether universal screening versus individualized, tailored history-taking would be the most effective in assisting clinicians in uncovering these histories and understanding its implications for the current management of their patient’s obesity. We also suggest careful research exploring the cultural and social implications of having these conversations as clinicians, and how clinicians may most sensitively and non-judgmentally approach their patients about this sensitive topic. Finally, data supporting the effectiveness of various interventions, as discussed above, is preliminary. Therefore, future directions should also work towards identifying which approaches for addressing childhood maltreatment may yield long-term positive outcomes.

References

Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Long MW, Gortmaker SL. Association of body mass index with health care expenditures in the United States by age and sex. PLoS One. 2021;16.

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–58.

Keeshin BR, Cronholm PF, Strawn JR. Physiologic changes associated with violence and abuse exposure: An examination of related medical conditions. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012. p. 41–56.

Mundi MS, Hurt RT, Phelan SM, Bradley D, Haller IV, Bauer KW, et al. Associations between experience of early childhood trauma and impact on obesity status, health, as well as perceptions of obesity-related health care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:408–19.

Alvarez J, Pavao J, Baumrind N, Kimerling R. The relationship between child abuse and adult obesity among California women. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:28–33.

Afifi TO, Macmillan HL, Boyle M, Cheung K, Taillieu T, Turner S, et al. Health Reports Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca

Mutlu H, Bilgiç V, Erten S, Aras Ş, Tayfur M. Evaluation of the relationship between childhood traumas and adulthood obesity development. Ecol Food Nutr. 2016;55:390–401.

Lawrence DM, Hunt A, Mathews B, Haslam DM, Malacova E, Dunne MP, et al. The association between child maltreatment and health risk behaviours and conditions throughout life in the Australian Child Maltreatment Study. Med J Aust. 2023;218:S34–9. This is a large cross-sectional study that provides rich information on various different types of child maltreatment and health risk behaviors and obesity, including self-harm, suicide attempt, substance use.

Hemmingsson E, Johansson K, Reynisdottir S. Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews. 2014;15:882–93

Fuemmeler BF, Dedert E, McClernon FJ, Beckham JC. Adverse childhood events are associated with obesity and disordered eating: Results from a U.S. population-based survey of young adults. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:329–33.

Sokol RL, Gottfredson NC, Poti JM, Shanahan ME, Halpern CT, Fisher EB, et al. Sensitive Periods for the Association Between Childhood Maltreatment and BMI. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57:495–502.

Bentley T, Widom CS. A 30-year follow-up of the effects of child abuse and neglect on obesity in adulthood. Obesity. 2009;17:1900–5.

Midei AJ, Matthews KA. Interpersonal violence in childhood as a risk factor for obesity: A systematic review of the literature and proposed pathways. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12.

Kisely S, Siskind D, Scott JG, Najman JM. Self-reported child maltreatment and cardiometabolic risk in 30-year-old adults. Intern Med J. 2023;53:1121–30.

Mason SM, Frazier PA, Renner LM, Fulkerson JA, Rich-Edwards JW. Childhood abuse–related weight gain: an investigation of potential resilience factors. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62:77–86. An important study because it is a large dataset followed longitudinally, evaluating the association between severe abuse and adulthood obesity, notably emotional abuse had the strongest association. Though there were several protective factors found associated with reduced BMI, notably, none of then significantly attenuated the average weight gain associated with abuse.

Ziobrowski HN, Buka SL, Austin SB, Duncan AE, Sullivan AJ, Horton NJ, et al. Child and Adolescent Abuse Patterns and Incident Obesity Risk in Young Adulthood. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63:809–17

Mason SM, MacLehose RF, Katz-Wise SL, Austin SB, Neumark-Sztainer D, Harlow BL, et al. Childhood abuse victimization, stress-related eating, and weight status in young women. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25:760-766.e2.

Power C, Pereira SMP, Li L. Childhood maltreatment and BMI trajectories to mid-adult life: Follow-up to age 50y in a British birth cohort. PLoS One. 2015;10.

Richardson AS, Dietz WH, Gordon-Larsen P. The association between childhood sexual and physical abuse with incident adult severe obesity across 13 years of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9:351–61.

Pittner K, Buisman RSM, van den Berg LJM, Compier-de Block LHCG, Tollenaar MS, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, et al. Not the root of the problem—hair cortisol and cortisone do not mediate the effect of child maltreatment on body mass index. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11.

Christie AJ, Matthews KA. Childhood poly-victimization is associated with elevated body mass index and blunted cortisol stress response in college women. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53:563–72.

Peckins MK, Negriff S, Schneiderman JU, Gordis EB, Susman EJ. The Moderating Role of Cortisol Reactivity on the Link Between Maltreatment and Body Mass Index Trajectory Across Adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65:239–47.

Midei AJ, Matthews KA, Bromberger JT. Childhood abuse is associated with adiposity in midlife women: Possible pathways through trait anger and reproductive hormones. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:215–23.

Danese A. Tan M. Childhood maltreatment and obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. Nature Publishing Group; 2014. p. 544–54.

Sacks RM, Takemoto E, Andrea S, Dieckmann NF, Bauer KW, Boone-Heinonen J. Childhood Maltreatment and BMI Trajectory: The Mediating Role of Depression. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:625–33.

Vámosi M, Heitmann BL, Kyvik KO. The relation between an adverse psychological and social environment in childhood and the development of adult obesity: A systematic literature review. Obesity Reviews. 2010. p. 177–84.

O’Neill A, Beck K, Chae D, Dyer T, He X, Lee S. The pathway from childhood maltreatment to adulthood obesity: The role of mediation by adolescent depressive symptoms and BMI. J Adolesc. 2018;67:22–30.

Rohde P, Ichikawa L, Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Linde JA, Jeffery RW, et al. Associations of child sexual and physical abuse with obesity and depression in middle-aged women. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:878–87.

McCarthy-Jones S, McCarthy-Jones R. Body mass index and anxiety/depression as mediators of the effects of child sexual and physical abuse on physical health disorders in women. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:2007–20.

Francis MM, Nikulina V, Widom CS. A prospective examination of the mechanisms linking childhood physical abuse to body mass index in adulthood. Child Maltreat. 2015;20:203–13.

Pederson CL, Wilson JF. Childhood emotional neglect related to posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and body mass index in adult women. Psychol Rep. 2009;105:111–26.

Duncan AE, Sartor CE, Jonson-Reid M, Munn-Chernoff MA, Eschenbacher MA, Diemer EW, et al. Associations between body mass index, post-traumatic stress disorder, and child maltreatment in young women. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;45:154–62.

Allison KC, Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Stunkard AJ. High self-reported rates of neglect and emotional abuse, by persons with binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:2874–83.

Amianto F, Spalatro AV, Rainis M, Andriulli C, Lavagnino L, Abbate-Daga G, et al. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect in obese patients with and without binge eating disorder: Personality and psychopathology correlates in adulthood. Psychiatry Res. 2018;269:692–9.

Abajobir AA, Kisely S, Williams G, Strathearn L, Najman JM. Childhood maltreatment and high dietary fat intake behaviors in adulthood: A birth cohort study. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;72:147–53.

Imperatori C, Innamorati M, Lamis DA, Farina B, Pompili M, Contardi A, et al. Childhood trauma in obese and overweight women with food addiction and clinical-level of binge eating. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;58:180–90.

Brown S, Mitchell TB, Fite PJ, Bortolato M. Impulsivity as a moderator of the associations between child maltreatment types and body mass index. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;67:137–46.

Font SA, Maguire-Jack K. Pathways from childhood abuse and other adversities to adult health risks: The role of adult socioeconomic conditions. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;51:390–9.

Fleischer T, Ulke C, Beutel M, Binder H, Brähler E, Johar H, et al. The relation between childhood adversity and adult obesity in a population-based study in women and men. Sci Rep. 2021;11.

Godoy LC, Frankfurter C, Cooper M, Lay C, Maunder R, Farkouh ME. Association of adverse childhood experiences with cardiovascular disease later in life: A review. JAMA Cardiol. American Medical Association; 2021. p. 228–35. Thorough review of association between ACEs and cardiovascular sequelae, including diabetes and obesity. ACEs are categorized into several different child maltreatment relevant domains, and the striking 2-fold higher risk of premature mortality is noted.

Stojek MM, Maples-Keller JL, Dixon HD, Umpierrez GE, Gillespie CF, Michopoulos V. Associations of childhood trauma with food addiction and insulin resistance in African-American women with diabetes mellitus. Appetite. 2019;141

Spann SJ, Gillespie CF, Davis JS, Brown A, Schwartz A, Wingo A, et al. The association between childhood trauma and lipid levels in an adult low-income, minority population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:150–5.

Sokol RL, Ennett ST, Shanahan ME, Gottfredson NC, Poti JM, Halpern CT, et al. Maltreatment experience in childhood and average excess body mass from adolescence to young adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;96.

Wall MM, Mason SM, Liu J, Olfson M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Blanco C. Childhood psychosocial challenges and risk for obesity in U.S. men and women. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9.

Rehkopf DH, Headen I, Hubbard A, Deardorff J, Kesavan Y, Cohen AK, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and later life adult obesity and smoking in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:488-492.e5.

Chieh AY, Liu Y, Gower BA, Shelton RC, Li L. Effect of race on the relationship between child maltreatment and obesity in Whites and Blacks. Stress. 2020;23:19–25.

Remigio-Baker RA, Hayes DK, Reyes-Salvail F. The Relationship of Adverse Childhood Events to Smoking, Overweight, Obesity and Binge Drinking Among Women in Hawaii. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:315–25.

Emery Tavernier RL, Mason SM, Levy RL, Seburg EM, Sherwood NE. Association of childhood abuse with behavioral weight-loss outcomes: Examining the mediating effect of binge eating severity. Obesity. 2022;30:96–105.

Cammack AL, Suglia SF. Mentorship in adolescence and subsequent depression and adiposity among child maltreatment survivors in a United States nationally representative sample. Prev Med (Baltim). 2023;166.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CW performed the literature review, and CW and RK both wrote the main manuscript text and reviewed all revisions and the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors Drs. Carmelle Wallace and Richard Krugman have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wallace, C., Krugman, R. More Than What You Eat: A Review on the Association Between Childhood Maltreatment and Elevated Adult BMI. Curr Nutr Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-024-00558-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-024-00558-4