Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review provides information on the prospect and effectiveness of ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTFs) produced locally without the addition of milk and peanut.

Recent Findings

The foods used in fighting malnutrition in the past decades contributed little to the success of the alleviation program due to their non-effectiveness. Hence, RUTFs are introduced to fight malnutrition. The peanut allergies, the high cost of milk, and the high production cost of peanut RUTF have made its distribution, treatment spread, and accessibility very slow, especially in areas where it is highly needed. There is a need, therefore, for a low-cost RUTF that is acceptable and effective in treating severe acute malnutrition among under-5 children.

Summary

This review shows both the success and failure of reported studies on the use of non-peanut and non-milk RUTF, including their cost of production as compared to the standard milk and peanut-based RUTF. It was hypothesised that replacing the milk ingredient component with legumes like soybeans can reduce the cost of production of RUTFs while also delivering an effective product in managing and treating severe acute malnutrition (SAM). Consumers generally accept them better because of their familiarity with the raw materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Based on cross-sectional surveys on the prevalence of stunting, over a million deaths are accountable for stunting [1] and [2] linked undernutrition to 45% of deaths among children below the age of 5 years. In Africa, 20% of infants die before their fifth birthday, while mortality affects 25.9% and 25% of children with stunted growth in South Africa and Uganda [3,4,5]. Aside from the mortality rate, the damaging effect of stunting is severe, and it is usually associated with intellectual impairment, severe infections, obesity, heart diseases, and diabetes in adolescence and adulthood [6,7,8,9]. It may be irreversible in under-5 children. The underlying cause of this malnutrition primarily results from inadequate dietary intake, inadequate breastfeeding, unemployment, and food insecurity induced by the high rate of income poverty [10]. According to the joint reports of UNICEF, WHO, IBRD, and WB, 149.2 million (22.0%), 45.4 million (6.7%), and 38.9 million (5.7%) of under-5 children globally were with stunted growth, wasted in weight, and overweight in 2020, respectively [2]. Unfortunately, Asia and Africa had the highest burden of this malnutrition [2]. In the document by [2], 53% and 41%, 70% and 27%, and 48% and 27% of these children were reported to be with stunted growth, wasted weight, and overweight in Asia and Africa, respectively. Among children with stunting, 23.3% were found in Southern Africa [2]. Although there was a reduction in children with stunted growth, in Southern Africa (29.1 to 23.3%) from 2000 to 2020, stunting in African children increased from 54.4 to 61.4 million from 2000 to 2020. Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is a major public health concern due to its long-term health repercussions and high mortality.

The foods commonly used as approach to fight malnutrition in the last years, mainly enriched cereals and legumes, and flour-based foodstuffs enhanced with legumes and cereals with or without sugar, oil, milk, and eggs contributed little to the success of the interventions due to their non-effectiveness in SAM treatment [11,12,13,14] and some significant complications such as flatulence. Moreover, clean and safe water is scarce in most rural areas in sub-Sahara Africa, and contaminated water for cooking food is mostly the norm. Also, populations in these areas have high food spoilage due to microbial increase from high geographical temperatures [15]. Hence, the use and adoption of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) have proven successful in the last few years.

RUTF has been a solution to this crisis in the last few decades [15]. Most RUTF consists of peanuts augmented with powdered milk, vitamins, vegetable oil, sugar, and mineral salts. RUTF’s peculiarities are a complete nutritional composition with amino acids, vitamins, mineral salts, essential fatty acids, high energy density (between 500 and 540 kcal/100g), and an extended shelf-life (low moisture content). These RUTF products can be appropriately used on-site during therapeutic programmes. For instance, it can be used at home without going to nutritional rehabilitation centres or hospitals [15].

Production of peanut-based ready-to-use therapeutic food (P-RUTF) has helped reduce this severe malnutrition in developing countries [16, 17]. Despite the significant progress made in combating SAM, the distribution and treatment spread of the peanut-based ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTFs) in severe acute malnourishment (SAM) affected areas is slow due to the high cost of production [18]. About 10% of the world’s children with stunted growth have access to the RUTF treatments [18].

Food assistance programmes led by United Nations (UN) used RUTF as a vital component in treating SAM in low- and middle-income countries amongst children aged 24–59 months in regions affected by food security. Although RUTFs promised to be a potential solution to the treatment of SAM, 80% of children with SAM had no access to RUTF [19]. Based on the report of [18], the number of children with stunted growth should be lowered by 65 million and save 3.7 million lives if nutrition intervention reaches them by 2025. There are two significant reasons why RUTFs were not adequately addressing SAM. These are accessibility (affordability) and availability. On average, peanut RUTF costs $41–51(USD) per child. The high cost of shipping, manufacturing and ingredients are major obstacles to increasing the availability of RUTFs [20••].

Milk’s high-quality protein, mineral profile, high lactose and bioactive properties (anticancer, satiating, antimicrobial, hypotensive, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and muscle and insulinotropic protein synthesis) incorporate milk as major raw material in RUTF production [21]. Hence, > 50% of the protein in RUTF should be from animal sources as specified by UN guidelines. In contrast to this affirmation statement, [22] reported that soya could substitute cow milk, given the sociocultural or medical discrepancies associated with cow milk in infants. Also, [23] declared that the nutritional profile of RUTF can be achieved without adding milk. A non-milk soya-maise-sorghum RUTF (SMS-RUTF) is as effective as P-RUTF in terms of weight gain, recovery rate and length of stay in the hospital in SAM treatment among children aged ≥ 24 months [24, 25]. This implies that P-RUTF, which is more expensive, should be used for children aged < 24 months, while SMS-RUTF should be used for children aged ≥ 24 months, which will reduce the cost of community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) programmes. Considering the number of children living with malnutrition to be reached and treated, coupled with the low available budget for SAM treatment, there is a need for low-cost, effective alternative RUTFs. These RUTFs will not include peanut, milk and whey proteins in their ingredients and will be locally sourced for and manufactured [26]. This review aims to provide information on the potentials and efficacies of locally produced RUTFs without peanuts and the addition of milk as a significant ingredient in treating SAM in children. In addition, the successes and failures of documented alternative RUTFs in the past few decades used in treating SAM were also explored.

Methodology

Grey literature and peer-review papers were scanned on the internet using the following keywords: ready-to-use therapeutic foods, efficacy, effectiveness, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) or World Health Organization (WHO). Google Scholar, Scopus and PubMed were used to search the literature. The search excluded any literature focusing on digestibility, molecular composition and policy dimensions of RUTF.

The Need for Alternative RUTF

RUTF is an energy-dense, mostly paste, lipid-based that needs no cooking and can easily resist bacterial contamination, a significant component in the CMAM [27]. In the production of RUTF, all ingredients are ground into < 200-µm particle size. The carbohydrate and protein components are embedded in a lipid matrix with little or no water [27, 28]. With a low water activity product, there is resistance against contamination by bacteria which grants safely stored RUTF at ambient temperatures [27]. P-RUTF is the most widely used RUTF. It constitutes milk powder, peanut butter, vegetable oil, sugar, vitamin and minerals [17, 27, 28], and it is like the WHO’s F-100 milk nutritionally [29, 30]. [31, 32•] reported several countries where RUTF has been successfully used in CMAM to treat children with SAM in poor resource settings. It has shown low fatality cases and high recovery rates with more significant weight gain.

Since 2015, UNICEF has requested manufacturers to propose products based on using alternative ingredients for review and future consideration, including non-peanut-based components or alternatives to milk. Not only can alternative ingredients generate cost savings in producing RUTF, but non-peanut recipes also increase acceptability in many countries where peanut-based products are not popular. Some alternative RUTFs use different legumes and cereals instead of peanuts (soy, chickpea flour, lentils or oats). They have a similar texture as paste and comply with the compositional guidance of the 2007 Joint statement, and most can use the existing machinery in RUTF manufacturing facilities [33].

Although there is high effectiveness in the management of SAM with P-RUTF, its cost of production is expensive. In 2009, a metric ton of non-peanut RUTF costs $1583, while peanut RUTF costs $2393 [25]. There is a limitation in processing these RUTFs in the needed countries due to the unavailability of locally produced milk powder and awkwardness in the available peanuts meeting the UN standards from aflatoxin levels [25]. Hence, there is a barrier in the procurement and production of RUTF in the needed countries, which led to the innovation of a new RUTF that uses locally available and acceptable materials for processing.

A substantial fraction of the children who suffered malnutrition came from the poorest parts of every country. However, most of these countries do not get enough support from non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to fight widespread acute malnutrition. There is, therefore, a need for cost-efficient and effective solutions to reduce malnutrition to achieve sustainable development goals as RUTF has changed the treatment of SAM as an excellent alternative to in-patient treatment [34]. Sadly, RUTFs were available to only 15% of those children in need of it worldwide [35]. In 2007, UNICEF used Plumpy’Nut (peanut-based) as the only RUTF for treating SAM in children [36]. Although the standard RUTF is potent in many cases, the challenges of its acceptability, cost and availability prevent it from reaching the target population. These caused researchers to study ways to improve acceptability amongst the target populace and reduce production costs. Based on research, food-assisted products obtained with locally sourced ingredients overcome the high cost and acceptability issues common with standard RUTFs [37]. Consequently, the potential of locally sourced and acquired RUTFs has motivated researchers to erupt alternative RUTFs that are cost-saving, acceptable by the recipients and efficient in treating SAM.

Many RUTFs that do not use peanut and milk protein have been trialled to increase local production, improve local acceptance and reduce cost. These formulations include egg powder and insect proteins [33]. In Colombia, UNICEF developed a fish-based wafer snack locally to treat SAM. Its production cost is 20% cheaper than the standard RUTF formulation, with good taste acceptability results among children affected with SAM [38]. A novel RUTF called Nutreal is nutritionally like Plumpy’Nut and made locally with the ingredients from the target population’s diet like pulses and cereals. There was a positive acceptability result, effective in SAM’s treatment among local consumers and reduced production cost than peanut-based RUTF not locally produced [39].

The formulation of alternative RUTFs led to the techniques modified to the target population’s local conditions and tastes [20••]. Based on efficacy studies, there is a broad acceptance of locally produced RUTFs among the recipients; hence, the alternative RUTFs can get to malnourished and at-risk children. In Bangladesh, RUTF made using rice, lentils and chickpea demonstrated positive and promising results [40]. Also, there were positive outcomes in the body composition and anthropometric indices of children treated with milk and soy-based RUTF [41•]. It was observed that both [40, 41•] improved on the past research on the efficacy of locally produced RUTF in the treatment of malnourished children in Malawi [17]. Additionally, [26] reported affordability and effectiveness in treating SAM using locally formulated chickpeas RUTFs in Ethiopia. Also, locally available RUTF produced from sorghum and millet showed efficacy in SAM treatment in Tanzania [42]. [43] reviewed that standard and novel RUTFs made little or no difference in recovery among children with SAM, and the effect of standard RUTF on relapse and mortality compared to the alternative novel RUTFs is unknown.

Furthermore, processing, animal source foods and fortification improve the protein quality of plant-based foods to meet protein requirements [44]. Based on [45], soybeans can replace animal products in infant formula and produce a favourable amino acid profile. Moreover, substituting soybeans with milk in the production of RUTF may enlarge its availability to malnourished children and reduce the cost of production; hence, this offers an alternative for RUTF production without or with little milk as raw materials [41•]. According to [45], standard milk-based formula (M-RUTF) containing 25% milk was more effective than whole soy flour-RUTF with 10% milk in treating kwashiorkor children. However, the undehulled soy used by [45] had less bioavailability, more anti-nutrients and lower amino acid digestibility. Such a nutrient profile implies that the body might not utilise the available nutrients for recovery. Alternatively, dehulling increases digestibility and lowers anti-nutrient availability in crops. Hence, processing methods like fermentation that will increase the bioavailability of nutrients should be implored during RUTF production.

Uhiara and Onwuka [46] used okra seeds extract to replace milk in RUTF production. The extract was used to feed rats for 3 weeks. The overall acceptability of the okra seeds extract-RUTF by fifteen-man semi-trained panellists showed no significant difference compared to the standard RUTF. Also, [47] replace milk with Locusta migratoria as the protein source in producing RUTFs. This locust-RUTF had tannin and phytate below the allowable limits in RUTFs, and other nutritional parameters met the requirements of WHO on RUTF; hence, it can be used as an alternative to milk in the production of RUTF.

Various Forms of RUTF

RUTFs appear in different forms, which include liquid, semi-solid and solid. Although RUTFs come in other forms, the semi-solid in the form of paste is the most popular form of RUTF. The liquid is usually informed of drinkable foods for easy swallowing among malnourished children. This was produced by [48] in Uganda. [49] produced a powder RUTF drink called Mushpro. This was made from mushroom, wheat flour, skimmed milk powder and cocoa powder. Also, [50] and [51] produced biscuits using mung bean flour and soybean flour.

The Potential and Effectiveness of Non-Peanut–Based RUTFs

Valid Nutrition (a research firm) used locally grown crops such as soya, maise and sorghum to produce peanut-free and milk-free SMS-RUTF. SMS-RUTF increases the prospect of using locally grown ingredients and reduces production costs. The efficacy of SMS-RUTF had been compared with P-RUTF. Although the effectiveness of SMS-RUTF was assessed by [25], the result was inconclusive. The SMS and P-RUTF were below the international standard with a high level of mortality. This inclusive result could be because of the measles and cholera outbreak during the study period. However, [42] improved the composition of SMS-RUTF using the results of [25]. These improvements included enrichment of SMS-RUTF with crystalline amino acids that led to high phytic acid (PA) and zinc molar ratio, PA and iron molar ratio and enhanced omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid profile ratio. Hence, the efficacy, haemoglobin, amino acid profile, weight gain, length of hospital stay, rate of recovery and participant body composition using SMS-RUTF were determined and compared with P-RUTF [42]. Phytic acid that binds divalent metallic ions and affects their absorption in the small intestine is absent in animal foods but present in plants. The SMS-RUTF used de-germinated maise, dehulled soybean and specially made mineral and vitamin premixes. The finished product met the recommended RUTF vitamin and mineral levels by WHO [29]. The iron and zinc levels were raised above the recommended concentration to compensate for high PA in the SMS-RUTF. Also, vitamin C content was increased to increase iron bioavailability in the product. Content of n-3 PUFA was increased while n-6 was decreased. In the production of RUTFs, [52] showed that the high level of phytates in legumes and cereals does not stop their use as raw materials to produce RUTF. Hence, there was an increase in vitamin C and an iron level of their formulated RUTF to achieve optimum iron absorption through increased vitamin C/iron weight ratio and phytic acid/iron molar ratio. The intended outcome was a boost in SAM survivors’ child development, resulting from reduced anaemia and improved iron status, which was linked to the inhibitory effect that milk protein has on iron absorption.

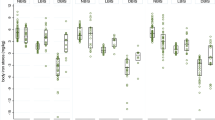

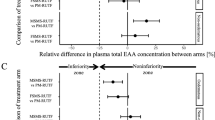

Milk-free-soya-maize-sorghum (FSMS-RUTF) and a 9.3% milk-soya-maise-sorghum (MSMS-RUTF) were compared to amino acid (AA) concentration of PM-RUTF in SAM children aged 6–59 months [53, 54]. Both milk-free (FSMS-RUTF) and 9.3% milk (MSMS-RUTF) showed no inferiority to the plasma leucine, methionine, cysteine and EAA concentration of PM-RUTF at discharge in children aged 6–59 months [42, 53]. FSMS-RUTF and MSMS-RUTF supplied proteins and amino acids like PM-RUTF for adequate recovery from SAM. Alternatively, [55] used unprocessed soy flour to treat SAM and observed a lower growth rate. Unprocessed soy flour contains anti-nutrients responsible for lower growth and recovery rate with 10% milk RUTF. The study was a clinical quasi-effectiveness trial and not a strict efficacy trial. Therefore, the lower growth and recovery rate obtained by [55] might result from anti-nutrients in the hull of soy. In a study conducted by [56], produced alternative-RUTF (A-RUTF), sorghum and soybean flour replaced 50% of peanut while non-fat dried milk and whey protein concentrate gave 50% of the protein. [56] reported A-RUTF to be inferior to standard-RUTF (S-RUTF) in the management of SAM due to lower mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) and weight gain; hence, A-RUTF did not facilitate recovery in SAM children.

The efficacy study of [42] on SMS-RUTF in Malawi checked the intention to treat (ITT), length of stay in the hospital (LOS) and recovery rate as compared to P-RUTF. ITT analysis met minimum international standards in the SMS-RUTF produced for children aged 24–59 months but contradicted 6–23 months. Lower recovery rate, higher mortality, defaulter and non-response rate were observed by [42] for SMS-RUTF in children aged 6–23 months, but the recovery rate was not inferior to the P-RUTF in children aged 24–59 months. Also, SMS-RUTF was not inferior to P-RUTF in weight gain, LOS and anaemia, while SMS-RUTF gives higher haemoglobin. Energy intake was higher in P-RUTF than SMS-RUTF among the two age groups. SMS-RUTF caused flatulence to a few children aged < 24 months and a higher report of dislike and side effects of SMS-RUTF among defaulted children [42]. Methionine, proline and tyrosine were lower in SMS-RUTF than in P-RUTF which may contribute to the inferiority of SMS-RUTF among children aged < 24 months [42]. Also, there was a reduction in the bioavailability of iron and zinc in the SMS-RUTF. However, the shift from milk to plant source could cause an increase in the phytic acid with a decrease in the bioavailability of zinc and iron.

Cost-Effectiveness of RUTFs

Although standard RUTF requires at least 50% of its protein from products of high protein quality like milk, the high cost of milk has increased the cost of production. Formulation of alternative for standard RUTF with lower or no milk is necessary for production scale-up and local availability. There is a need to assess the cost-effectiveness of no-milk or lower milk RUTF to comprehend if they could be allowed broader coverage in SAM treatment. In a study by [57], milk was replaced with soybeans to provide protein in the formulation of RUTFs. The results showed high effective products in the treatment of SAM, and their cost of production was cheaper than phumphy’nut. Alternative formulations of RUTF could potentially be optimised with micronutrients and possibly be made less expensive using other ingredients instead of skim milk. Table 1 summarises the potential of alternative ready-to-use therapeutic foods in managing acute malnutrition.

Ready-to-use supplementary foods (RUSF) are widely used in the cure of moderately acute malnutrition (MAM) [16, 58]. [26] reported the cost-effectiveness of four different RUSF (chickpea only, chickpea-maise-soya, super cereal (SC) and super cereal plus) used in treating MAM in Ethiopia. SC produced the required nutritional value at minimal cost in this report with no statistical significance among other products except super cereal plus and was well accepted by most of the targeted populace in the community. The ingredients that were used were procured, and production was local. [13] reported SC as a favourite meal for complementary and supplementary feeding programs for malnourished lactating and pregnant women, HIV and AIDS patients and under-5 children. Nevertheless, [12] reported SC as nutritionally inadequate and inappropriate in terms of energy density (0.5 kcal/g instead of the 0.8 kcal/g) that was recommended. Hence, even with the improved micronutrient profile, SC is ineffective in treating MAM among children of 6–23 months. However, the high amount of fibre and anti-nutrients reduced mineral absorption. Also, SC flour needs to be cooked before consumption, leading to extra costs from cooking utensils, fuel, and safe water. These inadequacies led to adding vegetable oil to meet energy and essential fatty acids requirements. Even though SC was the favourite meal among their studied population, [13] reported a lower recovery rate of 67% from malnutrition using SC than the 75% recovery rate standard, the minimum standard in response to a disaster. Females in all four products (chickpea only, chickpea-maise-soya, SC and SC+) with an exemption of Formular 1(chickpea only) have a lower recovery rate than males. In contrast, 6–11 months age group children had the highest recovery rate except for chickpea-maise-soya treatment. SC+ gave the highest recovery rate at ages 6–11 months. As a result of the sub-standard development in not being able to meet up with the standard recovery rate above, Super Cereal PLUS (SC+) was developed.

SC+ has milk to meet children’s micronutrient requirement of 6–23 months. Hence, SC+ met the WHO requirement for MAM treatment due to the improved micronutrient premix, sugar, oil and milk powder [28]. Although SC+ has the same premix as SC, the sugar, oil and milk content differ. SC+ has a higher energy density of 0.7 kcal/g than 0.5 kcal/g in SC when prepared.

Cost of Dietary Treatment for Malnutrition

SAM and stunting are accountable for 21% of disability-adjusted life years (DALY) for under-5 children [1, 59]. To reduce the death rate in under-5 children with severe acute malnutrition, [60] examined the cost-effectiveness of community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM). The decision tree model juxtaposes the cost and effectiveness of SAM treatment in the health services with and without CMAM in Malawi. [60] and [61] observed that for the base case (both children that survived or died in the CMAM programme), the cost of CMAM was US$42 and US$26 per DALY averted, while the worst-case (account for children that stayed and died in CMAM programme) scenario accounted for US$493 and US$335 per DALY. Based on the definition of WHO, CMAM was highly cost-effective in the base case because the cost per DALY falls under Malawi’s gross national income (GNI) per capita of US$250 [29, 60]. This was also within the scope of DALY for other child health interventions. In Bangladesh, [62] reported US$1344 and US$ 26 per DALY averted for in-patient treatment and community-based strategy cost, respectively, which result in the cost of community treatment of SAM being one-sixth of that of in-patient treatment. Also, CMAM was still cost-effective even in the worst case in Malawi and Bangladesh [60, 62]. [61] reported 15,016 DALYs to be averted with $23 per DALY averted estimated cost using community-based treatment and prevention programmes for SAM in slums in India. The disability burden and death associated with SAM may be more significant when considering other adverse effects like nutritional oedema.

The cost of community-based therapeutic care (CTC) accounts for US$53 per DALY gained, US$1760 per life saved and a mean cost of US$203 per child [63]. Based on the above report, 36%, 13%, 17% and 34% of the total cost were from RUTF used, health centre visits, hospital admissions and technical support, respectively, during programme establishment. Seventy per cent (70%) of the cost of an average CTC per child was from the price of RUFT and one life saved for every 8.7 children that received CTC [63].

Screening and treatment of different levels of acute malnutrition in under-five children in a community setting can be achieved through community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) [64]. Acute malnutrition can either be SAM or MAM. SAM relates to an 11-fold escalation mortality risk, and MAM is associated with threefold mortality risk. Hence, the cost of dietary treatment of SAM and MAM differs.

-

(a)

Cost of dietary treatment of SAM

The high cost of milk is a significant barrier to using milk-based RUTF [65]. About half of the expenses for SAM treatment are on therapeutic foods, and greater than 50% of these therapeutic foods are solely from milk powder [17, 66]. Based on Oakley et al.’s report, 10% milk with 15% soya RUTF used in the treatment of SAM had a slower recovery rate, weight and height gain than those receiving 25% milk. For the cost of milk-based RUTF production to be reduced, the content of skimmed milk was replaced with whey protein concentrate [56]. Sosanya et al. confirmed the lower cost of production in the locally produced RUTFs against the commercially produced RUTFs. [68] evaluated the cost-effectiveness of two CTC and therapeutic feeding centre (TFC) programmes in treating SAM. The mean cost per under-5 child treated with CTC and TFC was $134.88 and $284.56, respectively, while institutional cost per child treatment in CTC and TFC was $128.58 and $262.62, respectively. This higher institutional price could be connected to the fact that 43.2% of the institutional price of CTC went to RUTF. The authors concluded that CTC was more cost-effective than TFC. However, local production of RUTF can reduce the cost of RUTF, reducing the cost of CTC per child.

-

(b)

Cost of dietary treatment of MAM

SAM and MAM children have 11 and 3 times more likely to die than their non-malnourished counterparts [69]. Knowing fully well that if MAM is not well treated or controlled, it will lead to a more life-threatening condition like SAM. MAM management should be considered a public health issue. Based on the number of MAM children to be reached with RUSF, the cost of production of RUSF is an essential factor considering the global budget. Moreover, due to the high price of peanut and whey proteins, there is a need for alternative RUSF specifically for MAM children [70, 71]. Hence, chickpea-based RUSFs were improved [26].

According to [72], the ingredients approach was used to identify and analyse the cost of all resources used in the community treatment of MAM. The price includes the cost of screening, infrastructure and recurrent expenditure (supplementary food, personnel, materials, and medical supplies) per child. They used the trial document review and interviews with the key informant to estimate the cost. In the sum treatment of MAM based on [72] report, supplementary foods, personnel, materials and medical supplies cost 28–45%, 22–30% and 7–10% treatment cost, respectively.

The economic cost of the CMAM programme was estimated by [73] using a cost analysis design with a retrospective cross-sectional study in Ghana. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect information from under-5 children’s caregivers on household cost data. In contrast, interviews with crucial health personnel and reviewed documents were used to obtain the programme cost data. In [73] report, the programme’s economic cost was approximated to be $27,633.5, which refresher training made up 34% of the total cost. The financial household cost was approximately $1905.32 ($47.63 per household), with 79% direct cost. To treat one SAM case based on the report of [73] was $805.36 when using the CMAM protocol in Ghana.

Comparisons of Anti-nutritional Factors in RUTF Made from Different Local Foods Sources

The natural form of stored phosphate in plants is phytic acid. This phytate formed indigestible and insoluble complexes that inhibit minerals’ bioavailability. The use of added or intrinsic phytase enzyme to reduce phytic acid and the use of iron in a chelated form such as sodium iron ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) reduce the impeding effect of phytic acid [74]. Mineral bioavailability can be estimated by phytate and mineral molar ratio in improving iron absorption in legume and cereal-based foods [74]. Negative zinc balance can result from a phytate/zinc ratio equal to or greater than 15, significantly lowering zinc absorption [75, 76].

The ability of condensed tannins to precipitate gelatine, alkaloids and other proteins makes them anti-nutrients [77, 78]. The most available plant polyphenols are condensed tannins (proanthocyanidins and catechin). They are the polymers or oligomers of flavan-3-ols. Tannins in legume seeds contain anti-nutritional components that might prevent the utilisation of nutrients efficiently and interfere with digestion [79, 80]. Even though a high intake of tannins is associated with carcinogenesis, no evidence of toxicity on excess consumption of tannins in legumes has been reported. Instead, tannins have been reported to have antidiabetic and antioxidant properties [81]. Legumes’ protein becomes more digestible when trypsin inhibitors are deactivated. Trypsin inhibitors prevent protein digestion by contributing to the loss of chymotrypsin and trypsin in the gut [82]. Phytates, condensed tannins, and trypsin inhibitors were higher in metu2 (a locally made RUTF comprising peanut, honey, ghee and sorghum) than Plumpy’Nut. At the same time, aflatoxins in metu2 were lower than Plumpy’Nut and within acceptable limits [83]. [84] reduced the anti-nutritional factors in the chickpea before being used by roasting the chickpea in the sand at 250 °C with an internal temperature of 140 ± 10 °C for 10 min.

Comparisons of Macronutrients and Micronutrients of Some Already Produced Non-Milk RUTF with P-RUTF

Traditional foods of plant origin used for readily acceptable and nutritious foods like RUTF in developing countries increase the consumption of high-quality foods. The major constituents of the locally produced RUTF include pulses, cereals, minerals, vitamins, flavouring and skim-milk powder [85]. Legumes are an essential source of protein for low-income families. According to [86], legumes should be included in preparing effective, low-cost infant foods. [84] analysed chickpea-based RUTF-fed rats and compared the results with standard casein and peanut-based RUTF (Plumpy’Nut). Based on [84] report, the proximate analysis of chickpeas was related to Plumpy’nut. According to [84], true digestibility, biological value and net protein utilisation for chickpeas, Plumpy’Nut and casein were 83.78, 86.98 and 93.16; 87.77, 89.01 and 92.98 and 73.54, 77.42 and 86.58, respectively. However, chickpea RUTF and Plumpy’Nut showed no significant difference in other proteins measured except in casein. The protein efficiency ratio differs among the samples, and chickpea RUTF has a more excellent feed efficiency ratio than Plumpy’Nut.

Locally produced RUTF comprises lipids, carbohydrates and proteins with low indigestible fibre, vitamins and minerals that classify them as energy-dense foods; hence, it can treat SAM [84]. [83] compared metu2 with Plumpy’Nut in North-eastern Uganda and discovered that metu2 had higher energy content than plumpy'nut (528 kcal/100 g to 509 kcal). The vitamins K and A of metu2 were lower than the WHO recommendation for RUTF in SAM treatment. However, essential fatty acids, Mg and Na, meet SAM treatment and recovery requirements. Although the Zn content in the phumpy’nut was higher, it was recorded that both metu2 and phumpy’nut were below WHO recommendation. Peanut, date and soybean (AOB); acha, soybean, and cashew nut; crayfish (BOC) and peanut; guinea corn and soybean (PCO) were the three RUTFs produced by [67]. Their energy level was discovered to conform with the WHO energy recommendation of 520–550 kcal/100 g. Hence, these RUTFs (AOB, BOC and PCO) were apt for treating SAM in vulnerable individuals and under-5 children [67]. The protein content of the produced RUTFs was greater than that of Plumpy’Nut [67]. Also, the fat content of AOB and BOC was greater than the fat content of Plumpy’Nut. [84] reveal that Plumpy’Nut and locally produced RUTF possess the same digestibility. Both products showed no difference in their proximate composition, net protein utilisation (NPU), true digestibility (TD) and biological value (BV). It was concluded that the minimal presence of non-digestible fibres, vitamins and minerals makes the RUTF energy-dense and suitable for malnutrition treatments. The macro- and micro-nutrient contents of some locally produced RUTF are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Consumer Acceptability of Most Locally Produced RUTF

The senses of taste, touch, smell, and vision determine consumers’ acceptability of new products. Texture and appearance are two critical tests relating to the preferences shown by consumers. Using locally available raw materials to produce a new product has resulted in better acceptability by consumers due to their familiarity with the raw materials’ texture, taste and aroma [57, 87]. RUTF with 100% chickpea produced in Pakistan was preferred based on its smoothness, flavour, texture and overall acceptability due to the daily chickpea consumption among the Pakistans [88]. Also, RUTFs, made from soybean, maise and peanut, were highly acceptable by the consumers due to their familiarity with the taste of the raw materials [57]. The sensory properties scores of some locally produced RUTFs are shown in Table 4.

Conclusions

There are always means of improving the already produced RUTF for SAM treatment in all reviewed publications. These improvements include nutrient contents, formulations, effectiveness, cost of production and acceptability by the intending consumers. However, alternative RUTFs that can be efficacious, meet cost efficiency goals, accessible and acceptable to the recipients can be developed by researchers to meet the world demand for RUTF in treating SAM. This development has led to more research in developing novel RUTF using locally grown and available agricultural produce in different areas of the world that will efficiently manage SAM. Researchers are moving daily to achieve these goals by developing alternative RUTF using local agricultural products and reducing production costs.

The nutritional profiling in this review shows that the nutritional content of RUTF can be achieved without adding milk or using peanuts. This will reduce the cost of production of RUTF because milk stands as the most expensive raw material in the processing.

Also, processing methods used in the production of RUTF can affect the nutrient content of the final product. These processing methods may reduce the bioavailability of most nutrients and increase the anti-nutritional factors of the RUTFs. However, adding some enzymes can reduce the effects of these anti-nutrient factors.

This review showed that standard and novel RUTFs made little or no difference in recovery among children with SAM. The effect of standard RUTF on relapse and mortality compared to the alternative novel RUTFs is unknown. The above showed the need for a follow-up on the long-term outcome of alternative RUTFs in treating malnutrition.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Myatt M, Khara T, Schoenbuchner S, Pietzsch S, Dolan C, Lelijveld N, et al. Children who are both wasted and stunted are also underweight and have a high risk of death: a descriptive epidemiology of multiple anthropometric deficits using data from 51 countries. Arch Public Heal. 2018;76:1–11.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-018-0277-1.

UNICEF/WHO/WORLD BANK. Levels and trends in child malnutrition UNICEF / WHO / World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates Key findings of the. edition. World Heal Organ. 2021;2021:1–32.

Batool R, Butt MS, Sultan MT, Saeed F, Naz R. Protein-energy malnutrition: a risk factor for various ailments. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55:242–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2011.651543.

Gavhi F, Kuonza L, Musekiwa A, Villyen MN. Factors associated with mortality in children under five years old hospitalized for severe acute malnutrition in Limpopo province, South Africa, 2014–2018: A cross-sectional analytic study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232838.

Nalwanga D, Musiime V, Kizito S, Kiggundu JB, Batte A, Musoke P, et al. Mortality among children under five years admitted for routine care of severe acute malnutrition: a prospective cohort study from Kampala. Uganda BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02094-w.

Humphrey JH, Jones AD, Manges A, Mangwadu G, Maluccio JA, Mbuya MNN, et al. The sanitation hygiene infant nutrition efficacy (SHINE) Trial: rationale, design, and methods. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:S685-702. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ844.

Soliman A, De Sanctis V, Alaaraj N, Ahmed S, Alyafei F, Hamed N, et al. Early and long-term consequences of nutritional stunting: from childhood to adulthood. Acta Biomed. 2021;92:1–12. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v92i1.11346.

Zambruni M, Ochoa TJ, Somasunderam A, Cabada MM, Morales ML, Mitreva M, et al. Stunting is preceded by intestinal mucosal damage and microbiome changes and is associated with systemic inflammation in a cohort of Peruvian infants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;101:1009–17. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.18-0975.

Black RE, Levin C, Walker N, Chou D, Liu L, Temmerman M. Reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: key messages from Disease Control Priorities 3rd Edition. Lancet. 2016;388:2811–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00738-8.

Sanders D, Reynolds L. Ending stunting: transforming the health system so children can thrive. South African Child Gauge. 2017:68–76.

Bhandari N, Mohan SB, Bose A, Iyengar SD, Taneja S, Mazumder S, et al. Efficacy of three feeding regimens for home-based management of children with uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition: a randomised trial in India. BMJ Glob Heal. 2016;1:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000144.

De Pee S, Bloem MW. Current and potential role of specially formulated foods and food supplements for preventing malnutrition among 6-to 23-month-old children and for treating moderate malnutrition among 6-to 59-montn-old children. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30:434–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/15648265090303s305.

Karakochuk C, Van Den Briel T, Stephens D, Zlotkin S. Treatment of moderate acute malnutrition with ready-to-use supplementary food results in higher overall recovery rates compared with a corn-soya blend in children in southern Ethiopia: an operations research trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:911–6. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.029744.

Medoua GN, Ntsama PM, Ndzana ACA, Essa’A VJ, Tsafack JJT, Dimodi HT. Recovery rate of children with moderate acute malnutrition treated with ready-to-use supplementary food (RUSF) or improved corn-soya blend (CSB+): a randomized controlled trial. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:363–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015001238.

Santini A, Novellino E, Armini V, Ritieni A. State of the art of ready-to-use therapeutic food: a tool for nutraceuticals addition to foodstuff. Food Chem. 2013;140:843–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.098.

Manary M, Callaghan-gillespie M. Ready-to-use therapeutic food ( RUTF ) and ready-to-use supplementary food ( RUSF ) new approaches in formulation and sourcing. Sight Life. 2018;32:40–5.

Manary MJ. Local production and provision of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) spread for the treatment of severe childhood malnutrition. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27:83–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/15648265060273s305.

UNICEF. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Report. 2020:21–5.

Choudhury N, Ahmed T, Hossain MI, Islam MM, Sarker SA, Zeilani M, et al. Ready-to-use therapeutic food made from locally available food ingredients is well accepted by children having severe acute malnutrition in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull. 2018;39:116–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572117743929.

•• Clark LF. Are innovative ready to use therapeutic foods more effective, accessible and cost-efficient than conventional formulations? A review Outlook Agric. 2020;49:267–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030727020932184.This review considered the acceptability, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of RUTFs without peanuts and milk. It was concluded that there were positive results among the affected populace, hence the need for regional-specific formulations.

Michaelsen KF, Nielsen ALH, Roos N, Friis H, Mølgaard C. Cow’s milk in treatment of moderate and severe undernutrition in low-income countries. Nestle Nutr Work Ser Pediatr Progr. 2011;67:99–111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000325578.

Vandenplas Y, Castrellon PG, Rivas R, Gutiérrez CJ, Garcia LD, Jimenez JE, et al. Safety of soya-based infant formulas in children. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1340–60. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114513003942.

Dibari F, Diop EHI, Collins S, Seal A. Low-cost, ready-to-use therapeutic foods can be designed using locally available commodities with the aid of linear programming. J Nutr. 2012;142:955–61. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.156943.

Bahwere P, Banda T, Sadler K, Nyirenda G, Owino V, Shaba B, et al. Effectiveness of milk whey protein-based ready-to-use therapeutic food in treatment of severe acute malnutrition in Malawian under-5 children: a randomised, double-blind, controlled non-inferiority clinical trial. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10:436–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12112.

Irena AH, Bahwere P, Owino VO, Diop EI, Bachmann MO, Mbwili-Muleya C, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of a milk-free soy-maize-sorghum-based ready-to-use therapeutic food to standard ready-to-use therapeutic food with 25% milk in nutrition management of severely acutely malnourished Zambian children: an equivalence non-blin. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11:105–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12054.

Hailu T, Tessema M, Tesfaye B, Kebede A, Belay A, Ayana G, et al. Effectiveness of chickpea-based ready-to-use-supplementary foods for management of moderate acute malnutrition in Ethiopia: a cluster-randomized control trial. EC Nutr. 2017;5:201–15.

Briend A, Lacsala R, Prudhon C, Mounier B, Grellety Y, Golden MHN. Ready-to-use therapeutic food for treatment of marasmus. Lancet. 1999;353:1767–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01078-8.

Awuchi, Chinaza Godswill; Igwe, Victory Somtochukwu; Amagwula IO. Ready-to-use therapeutic foods ( RUTFs ) for remedying malnutrition and preventable nutritional diseases. Int J Adanced Acad Res. 2020;6:47–81.

World Health Organization, World Food Programme, United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition, United Nations Children’s Fund, WHO. Community-based management of severe acute malnutrition. A Jt Statement by World Heal Organ World Food Program United Nations Syst Standing Comm Nutr United Nations Child Fund. 2007:7.

Wagh DD, Deore BR. Ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF): an overview. Adv Life Sci Heal. 2015;2:1–15.

Rogers E, Myatt M, Woodhead S, Guerrero S, Alvarez JL. Coverage of community-based management of severe acute malnutrition programmes in twenty-one countries, 2012–2013. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:2012–3. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128666.

• Woeltje MM, Evanoff AB, Helmink BA, Culbertson DL, Maleta KM, Manary MJ, et al. Community-based management of acute malnutrition for infants under 6 months of age is safe and effective: analysis of operational data. Public Health Nutr. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021004894. This randomized clinical trial used RUTFs to treat SAM and MAM children between 6-9 months who were not hospitalized in rural Malawi. The products were shown to be safe and effective.

UNICEF. Ready to use therapeutic foods: market outlook. 2019.

Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Chu Y, Perin J, Zhu J, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet. 2016;388:3027–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8.

Lenters LM, Wazny K, Webb P, Ahmed T, Bhutta ZA. Treatment of severe and moderate acute malnutrition in low- and middle-income settings: a systematic review, meta-analysis and Delphi process. BMC Public Health. 2013;13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S23.

Guimón J, Guimón P. Innovation to fight hunger : the case of Plumpy ’ nut. 7th Globelics Int. Conf., 2009, p. 1–23.

Violette WJ, Harou AP, Upton JB, Bell SD, Barrett CB, Gómez MI, et al. Recipients’ satisfaction with locally procured food aid rations: comparative evidence from a three country matched survey. World Dev. 2013;49:30–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.01.019.

Sigh S, Roos N, Sok D, Borg B, Chamnan C, Laillou A, et al. Development and acceptability of locally made fish-based, ready-to-use products for the prevention and treatment of malnutrition in Cambodia. Food Nutr Bull. 2018;39:420–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572118788266.

Thapa BR, Goyal P, Menon J, Sharma A. Acceptability and efficacy of locally produced ready-to-use therapeutic food Nutreal in the management of severe acute malnutrition in comparison with defined food. Food Nutr Bull. 2017;38:18–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572116689743.

Ireen S, Raihan MJ, Choudhury N, Islam MM, Hossain MI, Islam Z, et al. Challenges and opportunities of integration of community based management of acute malnutrition into the government health system in Bangladesh: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3087-9.

• Hossain MI, Huq S, Islam MM, Ahmed T. Acceptability and efficacy of ready-to-use therapeutic food using soy protein isolate in under-5 children suffering from severe acute malnutrition in Bangladesh: a double-blind randomized non-inferiority trial. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59:1149–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-01975-w. This double-blind, randomized non-inferiority trial compared the efficacy and taste acceptability of Soy-based RUTF and milk-based RUTFs in under-5 children. It was found that both RUTFs were equally acceptable and efficacious. However, the cost implication in SAM management was lower with soy-based RUTF.

Bahwere P, Akomo P, Mwale M, Murakami H, Banda C, Kathumba S, et al. Soya, maize, and sorghum–based ready-to-use therapeutic food with amino acid is as efficacious as the standard milk and peanut paste–based formulation for the treatment of severe acute malnutrition in children: a noninferiority individually randomized con. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:1100–12. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.117.156653.

Schoonees A, Mj L, Musekiwa A, Nel E, Volmink J. Ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) for home-based nutritional rehabilitation of severe acute malnutrition in children from six months to five years of age (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019:50–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009000.pub3.www.cochranelibrary.com.

Wang L, Weller CL. Recent advances in extraction of nutraceuticals from plants. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2006;17:300–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2005.12.004.

Badger TM, Gilchrist JM, Pivik RT, Andres A, Shankar K, Chen JR, et al. The health implications of soy infant formula. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1668–72. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736U.

Uhiara NS, Onwuka G. Suitability of protein-rich extract from okra seed for formulation of ready to use therapeutic foods (RUTF). Niger Food J. 2014;32:105–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0189-7241(15)30102-8.

Akande OA, Oluwamukomi M, Osundahunsi OF, Ijarotimi OS, Mukisa IM. Evaluating the potential for utilising migratory locust powder (Locusta migratoria) as an alternative protein source in peanut-based ready-to-use therapeutic foods. Food Sci Technol Int. 2023;29:204–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/10820132211069773.

Nabuuma D, Nakimbugwe D. Development of the process for a drinkable plant-based infant Food. J Nutr Food Sci. 2013;03. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9600.1000210.

Wasnik VR, Rathi M. Effect of locally made ready-to-use therapeutic food (Mushpro Health Drink Powder - MHDP) for treatment of malnutrition on children aged 6 to 72 months in tribal area of Amravati District of Maharashtra, India: a randomized control trial. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Public Heal. 2012;4:1472–87.

Purwestri RC, Scherbaum V, Inayati DA, Wirawan NN, Suryantan J, Bloem MA, et al. Impact of daily versus weekly supply of locally produced ready-to-use food on growth of moderately wasted children on Nias Island. Indonesia ISRN Nutr. 2013;2013:1–10. https://doi.org/10.5402/2013/412145.

Scherbaum V, Purwestri RC, Stuetz W, Inayati DA, Suryantan J, Bloem MA, et al. Locally produced cereal/nut/legume-based biscuits versus peanut/milk-based spread for treatment of moderately to mildly wasted children in daily programmes on Nias Island, Indonesia: An issue of acceptance and compliance? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2015;24:152–61. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.1.15.

Akomo P, Bahwere P, Murakami H, Banda C, Maganga E, Kathumba S, et al. Soya, maize and sorghum ready-to-use therapeutic foods are more effective in correcting anaemia and iron deficiency than the standard ready-to-use therapeutic food: randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7170-x.

Sato W, Furuta C, Matsunaga K, Bahwere P, Collins S, Sadler K, et al. Amino-acid-enriched cereals ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTF) are as effective as milk-based RUTF in recovering essential amino acid during the treatment of severe acute malnutrition in children: an individually randomized control trial in Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201686.

Sato W, Furuta C, Akomo P, Bahwere P, Collins S, Sadler K, et al. Amino acid-enriched plant-based RUTF treatment was not inferior to peanut-milk RUTF treatment in restoring plasma amino acid levels among patients with oedematous or non-oedematous malnutrition. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91807-x.

Oakley E, Reinking J, Sandige H, Trehan I, Kennedy G, Maleta K, et al. A ready-to-use therapeutic food containing 10% milk is less effective than one with 25% milk in the treatment of severely malnourished children. J Nutr. 2010;140:2248–52. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.123828.

Kohlmann K, Callaghan-Gillespie M, Gauglitz JM, Steiner-Asiedu M, Saalia K, Edwards C, et al. Alternative ready-to-use therapeutic food yields less recovery than the standard for treating acute malnutrition in children from Ghana. Glob Heal Sci Pract. 2019;7:203–14. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00004.

Wamunga FW, Wamunga BJ. Locally Developed ready-to-use-therapeutic-food (RUTF) for management of malnutrition using animal models. J Clin Nutr Diet. 2017;03. https://doi.org/10.4172/2472-1921.100044.

Greiner T. Advantages, disadvantages and risks of ready-to-use foods. Breastfeed Briefs. 2014;56(57):1–22.

Puett C, Bulti A, Myatt M. Disability-adjusted life years for severe acute malnutrition: Implications of alternative model specifications. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22:2729–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019001393.

Wilford R, Golden K, Walker DG. Cost-effectiveness of community-based management of acute malnutrition in Malawi. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:127–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czr017.

Goudet S, Jayaraman A, Chanani S, Osrin D, Devleesschauwer B, Bogin B, et al. Cost effectiveness of a community based prevention and treatment of acute malnutrition programme in Mumbai slums. India PLoS One. 2018;13:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205688.

Puett C, Sadler K, Alderman H, Coates J, Fiedler JL, Myatt M. Cost-effectiveness of the community-based management of severe acute malnutrition by community health workers in southern Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28:386–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs070.

Bachmann MO. Cost effectiveness of community-based therapeutic care for children with severe acute malnutrition in Zambia: Decision tree model. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2009;1:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-7-2.

Ackatia-Armah RS, McDonald CM, Doumbia S, Erhardt JG, Hamer DH, Brown KH. Malian children with moderate acute malnutrition who are treated with lipid-based dietary supplements have greater weight gains and recovery rates than those treated with locally produced cereal-legume products: a community-based, cluster-randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:632–45. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.069807.

Scherbaum V, Srour ML. Milk products in the dietary management of childhood undernutrition - a historical review. Nutr Res Rev. 2018;31:71–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422417000208.

Purwestri RC, Scherbaum V, Inayati DA, Wirawan NN, Suryantan J, Bloem MA, et al. Cost analysis of community-based daily and weekly programs for treatment of moderate and mild wasting among children on Nias Island. Indonesia Food Nutr Bull. 2012;33:207–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482651203300306.

Sosanya M, Nweke G, Ifitezue L. Formulation and evaluation of ready-to-use therapeutic foods using locally available ingredients in Bauchi. Nigeria Eur J Nutr Food Saf. 2017;8:1–10. https://doi.org/10.9734/ejnfs/2018/37833.

Tekeste A, Wondafrash M, Azene G, Deribe K. Cost effectiveness of community-based and in-patient therapeutic feeding programs to treat severe acute malnutrition in Ethiopia. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2012;10:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-10-4.

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382:427–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X.

Golden MH. Proposed recommended nutrient densities for moderately malnourished children. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30. https://doi.org/10.1177/15648265090303s302.

Manary M, Callaghan-Gillespie M. Role of optimized plant protein combinations as a low-cost alternative to dairy ingredients in foods for prevention and treatment of moderate acute malnutrition and severe acute malnutrition. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2020;93:111–20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000503347.

Isanaka S, Barnhart DA, McDonald CM, Ackatia-Armah RS, Kupka R, Doumbia S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of community-based screening and treatment of moderate acute malnutrition in Mali. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019;4:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001227.

Abdul-Latif A-MC, Nonvignon J. Economic cost of community-based management of severe acute malnutrition in a rural district in Ghana. Health (Irvine Calif). 2014;06:886–9. https://doi.org/10.4236/health.2014.610112.

Akomo PO, Egli I, Okoth MW, Bahwere P, Cercamondi CI, Zeder C, Njage PMK, Owino VO. Estimated iron and zinc bioavailability in soybean-maize-sorghum ready to use foods: effect of soy protein concentrate and added phytase. J Food Process Technol. 2016;07. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7110.1000556.

Gibson RS, Raboy V, King JC. Implications of phytate in plant-based foods for iron and zinc bioavailability, setting dietary requirements, and formulating programs and policies. Nutr Rev. 2018;76:793–804. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuy028.

Mahati Sri Lalitha R, Hymavathi T, Devi KU, Robert TP. Nutrients, phytochemicals and antioxidant activity in whole and dehulled nutri-cereal based multigrain extruded snacks. Int J Chem Stud. 2018;6:765–9.

Smeriglio A, Barreca D, Bellocco E, Trombetta D. Proanthocyanidins and hydrolysable tannins: occurrence, dietary intake and pharmacological effects. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:1244–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13630.

Sallam IE, Abdelwareth A, Attia H, Aziz RK, Homsi MN, von Bergen M, et al. Effect of gut microbiota biotransformation on dietary tannins and human health implications. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1–34. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9050965.

Sathya A, Siddhuraju P. Effect of processing methods on compositional evaluation of underutilized legume, Parkia roxburghii G. Don (yongchak) seeds. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52:6157–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-015-1732-4.

Ojo MA. Tannins in foods: nutritional implications and processing effects of hydrothermal techniques on underutilized hard-to-cook legume seeds-a review. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2022;27:14–9.

Kunyanga CN, Imungi JK, Okoth M, Momanyi C, Biesalski HK, Vadivel V. Antioxidant and antidiabetic properties of condensed tannins in acetonic extract of selected raw and processed indigenous food ingredients from Kenya. J Food Sci. 2011;76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02116.x.

Popova A, Mihaylova D. Antinutrients in plant-based foods: a review. Open Biotechnol J. 2019;13:68–76. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874070701913010068.

Andrew AK, Yiga P, Kuorwel KK, Chewere T. Nutrient and anti-nutrient profile of a local formula from sorghum, peanut, honey and gheE (Metu2) for treatment of severe acute malnutrition. J Food Res. 2018;7:25. https://doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v7n2p25.

Hassan JU, Iqbal S, Naeem N, Frasat, Nasir M. Development, efficacy and comperative analysis of novel chickpea based ready-to-use therapeutic food. J Anim Plant Sci. 2016;26:1843–9.

Michaelsen KF, Hoppe C, Roos N, Kaestel P, Stougaard M, Lauritzen L, et al. Choice of foods and ingredients for moderately malnourished children 6 months to 5 years of age. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30. https://doi.org/10.1177/15648265090303s303.

Isanaka S, Nombela N, Djibo A, Poupard M, Van Beckhoven D, Gaboulaud V, et al. Effect of preventive supplementation with ready-to-use therapeutic food on the nutritional status, mortality, and morbidity of children aged 6 to 60 months in Niger: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301:277–85. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2008.1018.

Kure OA, Wyasu G. Influence of natural fermentation, malt addition and soya-fortification on the sensory and physico-chemical characteristics of Ibyer-Sorghum gruel. Adv Appl Sci Res. 2013;04:345–9.

Javed F, Sharif MK, Pasha I, Jamil A. Probing the nutritional quality of ready-to-use therapeutic foods developed from locally grown peanut, chickpea and mungbean for tackling malnutrition. Pakistan J Agric Sci. 2021;58:205–12. https://doi.org/10.21162/PAKJAS/21.700.

Brown M, Nga TT, Hoang MA, Maalouf-Manasseh Z, Hammond W, Thuc TML, et al. Acceptability of two ready-to-use therapeutic foods by HIV-positive patients in Vietnam. Food Nutr Bull. 2015;36:102–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572115587498.

Bahwere P, Balaluka B, Wells JCK, Mbiribindi CN, Sadler K, Akomo P, et al. Cereals and pulse-based ready-to-use therapeutic food as an alternative to the standard milk- and peanut paste-based formulation for treating severe acute malnutrition: a noninferiority, individually randomized controlled efficacy clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:1145–61. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.119537.

Kangas ST, Kaestel P, Salpéteur C, Nikièma V, Talley L, Briend A, et al. Body composition during outpatient treatment of severe acute malnutrition: results from a randomised trial testing different doses of ready-to-use therapeutic foods. Clin Nutr. 2020;39:3426–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.02.038.

Owino VO, Irena AH, Dibari F, Collins S. Development and acceptability of a novel milk-free soybean-maize-sorghum ready-to-use therapeutic food (SMS-RUTF) based on industrial extrusion cooking process. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10:126–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00400.x.

•• Selvaraj K, Mamidi RS, Peter R, Kulkarni B. Acceptability of locally produced ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF) in malnourished children: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Indian J Pediatr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-022-04079-2. This randomized, double-blind, crossover study compared the acceptability of locally produced RUTF with the standard RUTF. It concluded that the acceptability of both RUTFs by the malnourished children was similar.

Bahwere P, Sadler K, Collins S. Acceptability and effectiveness of chickpea sesame-based ready-to-use therapeutic food in malnourished HIV-positive adults. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2009;3:67–75. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S4636.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Venda.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akinmoladun, O.F., Bamidele, O.P., Jideani, V.A. et al. Severe Acute Malnutrition: The Potential of Non-Peanut, Non-Milk Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Foods. Curr Nutr Rep 12, 603–616 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-023-00505-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-023-00505-9