Abstract

Purpose of Review

To examine and synthesise recent evidence on the role of grandparents in shaping children's dietary health.

Recent Findings

The influence of grandparents on children’s dietary health was evident across studies. Grandparents frequently provide their grandchildren with meals and snacks, and engage in many of the same feeding practices used by parents. Although grandparents report providing their grandchildren with healthy foods, the provision of treat foods high in sugar or fat was a common finding. This provision led to family conflict, with the indulgent behaviours of grandparents seen by parents as a barrier to healthy eating.

Summary

Grandparents are exerting significant influence on child dietary health. Efforts are needed to ensure these care providers are considered key stakeholders in the promotion of healthy eating and are targeted in policies and programs addressing children’s diets. Research that determines how to best support grandparents to foster healthy behaviours in children is critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Poor nutrition has been highlighted as a key modifiable factor that plays a crucial role in the development and maintenance of multiple non-communicable diseases [1]. The promotion of a diet characterised by (i) adequate consumption of fruit, vegetables, and wholegrains and (ii) infrequent consumption of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods and beverages is thus considered important to health outcomes, with such a diet reducing the risk of all-cause mortality and diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cancer [2,3,4,5,6].

Given that dietary habits established early in life track into adulthood [7], the promotion of a healthy diet in childhood to reduce the risk of diet-related chronic disease at all stages of the life course has been identified as a global health priority [8]. A range of individual, familial, social, and environmental factors shape children’s eating behaviours [9]. The role of parents is considered particularly important. Parents influence their children’s diet directly as gatekeepers of the eating environment and indirectly through their role as nutrition educators and modellers of food choice [10,11,12]. Although parents remain critical, recent decades have seen societal factors such as increased maternal participation in the workforce and the reduced affordability, availability, and flexibility of formal childcare arrangements contribute to worldwide increases in grandparents’ involvement as secondary care providers to their grandchildren [13,14,15,16,17]. Accordingly, it has been suggested that grandparents be considered important stakeholders in the promotion of healthy eating among children [18•]. The purpose of this review was to examine and synthesise recent work exploring the role of grandparents in shaping children's dietary health and eating behaviours.

Method

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

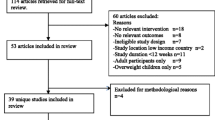

A comprehensive search of the following databases was conducted for original research articles published from 1st January 2013 to the 31st December 2022: Google Scholar, EBSCO, Medline, PubMed, ProQuest, Science Direct, SCOPUS, and Web of Science. The search terms were (grandparents OR grandcarers OR grandmothers OR grandfathers) AND (grandchildren OR grandkids) AND (diet OR nutrition OR feeding). To be included in this review, studies must have been available in full text and published in English. Only studies exploring the role of non-custodial, non-residing grandparents were eligible for inclusion; studies involving custodial or co-residing grandparents were excluded. A separate search was conducted for meta-analyses and systematic reviews. These are not included in this narrative review, but a list of relevant reviews is presented in the online supplementary material.

A total of 2,167 studies was identified. After screening these for relevance and eligibility, 25 studies remained.

Findings

A summary of each of the studies reviewed is presented in Table 1. The influence of grandparents on children’s dietary health was evident across all studies. The sections below outline the findings according to specific areas of influence.

Provision of Meals and Snacks

Grandparents were found to frequently provide their grandchildren with meals and snacks [18•, 19]. For example, a study by Jongenelis et al. [18•] found that 98% of surveyed grandparents reported ‘usually’ providing at least 1 meal or snack to the grandchildren for whom they provide care. Snack provision was most common (82%), followed by lunch provision (57%) and then dinner (48%). McArthur et al. [19] examined the number of snacks provided by grandparents, with an average of 2.75 snacks provided by grandparents each caregiving occasion. Nearly one-fifth of grandparents reported providing 4 or more snacks per caregiving occasion.

Types of Foods Provided

The provision of ‘treat foods’ high in sugar or fat (e.g. chocolate, sweets, ice-cream, and sugary drinks) was explored in multiple studies [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Such foods were found to play a significant role in grandparents’ food provision [22]. Indulging children with treat foods was considered by both parents and grandparents to be part of the grandparental role, with grandparents reporting that it was their right to spoil their grandchildren with such foods [24,25,26, 28, 29••, 30••]. Treats were found to be embedded in grandparent–grandchild routines and relationships, with many studies finding the provision of such foods to be a means through which grandparents expressed their love and care [21,22,23, 29••, 30••]. Nutritious meals were still prepared by grandparents for their grandchildren, but treat foods were used to strengthen the relationship bond.

Some grandparents believed it was acceptable to indulge their grandchildren as they were not primarily responsible for food provision [25, 30••, 31, 32]. They sought to counterbalance the strict rules of parents with a more lenient approach to grandchild feeding [30••]. Other motivators behind treat provision included (i) the belief that restricting treat foods created a desire for them, and that exposure provided an important means by which children learnt about moderation and self-control [29••] and (ii) rewarding good behaviour and accomplishments [22, 29••, 30••].

Not all findings suggested that grandparents’ food provision was problematic [18•, 22, 23, 29••, 32, 33]. In a study by Jongenelis et al. [18•], grandparents reported serving their grandchildren healthy foods and beverages (e.g. fresh fruit; milk, cheese, or yoghurt; vegetables; grain and cereal foods) more frequently than unhealthy foods and beverages (e.g. sugary drinks). In a study by Knight et al. [32], some children and their mothers reported consuming a greater variety of food because of grandparents’ direct involvement in providing them with meals. In other studies, some grandparents reported feeling a strong sense of responsibility to assist parents with raising healthy children and thus engaged in food provision practices they believed enhanced their grandchildren’s wellbeing [23, 29••].

Comparisons Between Grandparents and Parents

Mixed results were observed in studies that compared grandparents’ and parents’ food provision [22, 28, 34••]. In a study by Marr et al. [34••], there were no significant differences in the nutritional content of meals and snacks served by grandparents compared to parents. By contrast, in a study by Eli et al. [28], both grandparents and parents reported that grandparents were more likely than parents to provide children with unhealthy foods and beverages on a regular basis. In a study by O’Donohoe et al. [22], both grandparents and parents agreed that grandparents generally had more time for cooking meals from scratch whereas busy parents did not.

Feeding Practices

Several studies explored the feeding practices of grandparents [22, 24, 25, 29••, 34••, 35••, 36,37,38,39]. Grandparents appeared to use positive feeding practices (i.e. practices that lead to favourable dietary behaviours) more often than negative feeding practices (i.e. practices that lead to unfavourable dietary behaviours). The promotion of balance and variety was the most frequently used positive feeding practice [34••, 35••]. Other positive feeding practices in which grandparents engaged included modelling healthy eating, monitoring children’s food intake, providing a healthy eating environment by making healthy foods available and limiting the amount of unhealthy foods available, teaching about nutrition, and praising children for healthy eating [22, 24, 25, 29••, 34••, 35••, 36, 37].

In terms of negative feeding practices, a study by Jongenelis et al. [35••] observed scores above the midpoint for just one negative feeding practice—control over eating. All other negative feeding practices (pressure to eat, instrumental feeding, emotional feeding) were below the midpoint. Similarly, most studies have found that using food to ameliorate negative emotions is an uncommon feeding practice among grandparents [29••, 34••, 38].

Just one study appears to have examined the association between grandparents’ feeding practices and the diet quality of their grandchildren. In this study by Jongenelis et al. [35••], positive feeding practices were identified as being more important correlates of diet quality than negative feeding practices. The provision of a healthy food environment emerged as the most important positive feeding practice; it was found to be positively associated with grandchild fruit and vegetable consumption and negatively associated with grandchild savoury and sweet snack consumption. Limit setting was also found to be important, with grandparents who engaged in this feeding practice reporting that their grandchild consumed fewer savoury snacks and sugary drinks. Mixed results were observed for other feeding practices.

Comparisons Between Grandparents and Parents

Some studies compared the feeding practices of grandparents and parents [34••, 36, 38]. In terms of positive feeding practices, findings suggested that grandparents were significantly more likely than parents to report creating a healthy eating environment [34••, 36]. They were also more likely to allow children to have control during mealtimes [36]. However, grandparents were less likely to encourage balance and variety, model healthy eating, monitor child food intake, and teach about nutrition [34••, 36, 38]. In terms of negative feeding practices, grandparents were less likely than parents to report using food as a reward [36]. However, they were more likely than parents to report (i) using food to regulate emotions and (ii) restricting food due to weight concerns [36, 38].

Feeding Style

Just one study examining the feeding styles of grandparent care providers was found. In this study by Marr et al. [34••], the most common feeding style reported by grandparents was ‘indulgent’ (41%), followed by authoritative (23%), then uninvolved and authoritarian (both 18%).

Family Disagreement over Food Provision

An important finding that was identified in many studies was the differing opinions regarding child feeding held by parents and grandparents and the potential for this to (i) prevent the adoption of healthy dietary practices and/or (ii) result in the adoption of unhealthy dietary practices [23, 25, 28, 31, 39, 40]. While grandparents generally believed that parents had ultimate authority over feeding and reported respecting the decisions of parents regarding their grandchildren’s food options [22, 24, 25, 28, 29••, 30••, 41•], the extent to which they complied with parents’ feeding instructions varied. For example, in a study by Bektas et al. [31], most grandmothers reported disagreeing at times with parents’ instructions for what and how to feed their child. They thus ignored these instructions, providing their grandchildren with food and drinks that parents did not allow (e.g. sweets, processed foods, and fruit juice), usually in secret. In other studies, grandparents reported engaging in only “minor subversions” of parents’ feeding rules [22, 28].

In parents’ reports of grandparent feeding, it was noted that grandparents held permissive attitudes towards their grandchildren’s eating habits [40]. This reportedly resulted in (i) restrictions of certain foods being inconsistently enforced and (ii) parents’ efforts to promote healthy eating habits being contradicted [40, 42]. The indulgent behaviours of grandparents were seen as problematic, a barrier to healthy eating, and a source of conflict and frustration [26, 32, 41•]. While parents noted that they had the final say, this did not come easy [41•]. Parents also noted that conflicting beliefs regarding food provision put pressure on them to adopt undesirable feeding behaviours [41•]. Mothers from culturally and linguistically diverse groups additionally reported struggling with their children’s grandparents when they fed children non-traditional foods [42].

Both grandparents and parents were reluctant to discuss their differences openly, fearing family conflict [31]. Parents were reliant on grandparents for childcare and did not want to impose on grandparent–grandchild relationships [32]. Grandparents wished to maintain family harmony and ensure ongoing access to their grandchildren [29••, 30••]. Accordingly, both parties reported complying with the other even when they did not agree [29••, 30••].

Conclusions

Findings from research published over the last decade suggest that grandparents are exerting significant influence on child dietary health. They frequently provide their grandchildren with meals and snacks and engage in many of the same feeding practices used by parents. Although grandparents report providing their grandchildren with healthy foods, the provision of treat foods high in sugar or fat was a common finding across multiple studies. This provision led to family conflict, with the indulgent behaviours of grandparents seen by parents as a barrier to healthy eating and a source of frustration.

As grandparents become increasingly important providers of childcare globally, efforts are needed to ensure they are considered key stakeholders in the promotion of healthy eating and are targeted in policies and programs addressing children’s diets. While grandparents may not perceive themselves to be primarily responsible for child feeding, the high volume of care in which they engage means the frequent provision of treat foods could be problematic. It is promising, however, that grandparents appear motivated to assist parents with raising healthy children. Communicating to grandparents their importance and encouraging them to become champions of healthy eating may be a means by which motivation can be increased.

Research that determines how to best support grandparents to foster healthy lifestyle behaviours in children would make an important contribution to efforts to prevent of poor diet and improve health outcomes. The development of intergenerational programs that recognise the influence of all caregivers and encourage them to contribute to the goal of promoting healthy eating in children is also worthy of consideration. Such programs can assist with identifying caregiver differences that may be undermining efforts to provide children with a healthy food environment. They can also be used to optimise communication between caregivers and thus represent a potential means by which (i) the intergenerational conflict that serves as a barrier to promoting healthy eating in children may be reduced and (ii) the likelihood of children receiving congruent messages from all family members involved in their care can be increased.

It must be noted that this review explored studies published in English and only included work on non-residing grandparents. Accordingly, population groups in which co-residence of grandparents is common (e.g. South-East Asian, Chinese Asian, and South and Central Asian groups) were not represented. The influence of grandparents on grandchildren’s dietary health is likely to differ among these groups [43] and the conclusions drawn here cannot be generalised.

To conclude, the clear contribution of grandparents to children’s dietary health highlights the importance of including these caregivers in family interventions addressing lifestyle behaviours. Efforts are urgently needed to develop appropriate and effective tools that increase grandparents’ engagement in practices that support children to adopt positive behaviours and live healthy lives.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, Kumanyika S, Lobstein T, Neal B, et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12087.

Joshipura KJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Speizer FE, et al. The effect of fruit and vegetable intake on risk for coronary heart disease. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(12):1106–14. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00010.

Ness AR, Maynard M, Frankel S, Smith GD, Frobisher C, Leary SD, et al. Diet in childhood and adult cardiovascular and all cause mortality: the Boyd Orr cohort. Heart. 2005;91(7):894–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2004.043489.

Sotos-Prieto M, Bhupathiraju SN, Mattei J, Fung TT, Li Y, Pan A, et al. Changes in diet quality scores and risk of cardiovascular disease among US men and women. Circ J. 2015;132(23):2212–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017158.

Wang PY, Fang JC, Gao ZH, Zhang C, Xie SY. Higher intake of fruits, vegetables or their fiber reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Diabetes Investigation. 2016;7(1):56–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.12376.

Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, Zhu M, Zhao G, Bao W, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Br Med J. 2014;349:g4490. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g4490.

Mikkilä V, Räsänen L, Raitakari OT, Pietinen P, Viikari J. Consistent dietary patterns identified from childhood to adulthood: The cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Br J Nutr. 2005;93:923–31. https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN20051418.

World Health Organization. Ambition and Action in Nutrition 2016–2025. Geneva: WHO; 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241512435. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

Patrick H, Nicklas TA. A review of family and social determinants of children’s eating patterns and diet quality. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24(2):83–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2005.10719448.

Kiefner-Burmeister AE, Hoffmann DA, Meers MR, Koball AM, Musher-Eizenman DR. Food consumption by young children: A function of parental feeding goals and practices. Appetite. 2014;74:6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.11.011.

Moore ES, Wilkie WL, Desrochers DM. All in the family? Parental roles in the epidemic of childhood obesity. J Consum Res. 2016;43:824–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw059.

Sleddens EF, Kremers SP, Stafleu A, Dagnelie PC, De Vries NK, Thijs C. Food parenting practices and child dietary behavior: Prospective relations and the moderating role of general parenting. Appetite. 2014;79:42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.04.004.

Jappens M, Van Bavel J. Regional family norms and child care by grandparents in Europe. Demogr Res. 2012;27:85–120.

Pulgarón ER, Marchante AN, Agosto Y, Lebron CN, Delamater AM. Grandparent involvement and children’s health outcomes: The current state of the literature. Fam Syst Health. 2016;34:260–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000212.

Geurts T, Van Tilburg T, Poortman A, Dykstra PA. Child care by grandparents: Changes between 1992 and 2006. Ageing Soc. 2015;35:1318–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X14000270.

Laughlin L. Who’s minding the kids? Child care arrangements: Spring 2011. U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Adminstration; 2013. p. 70–135.

Rutter J. 2016 Childcare Survey. London: United Kingdom Family and Childcare Trust; 2016.

• Jongenelis MI, Talati Z, Morley B, Pratt IS. The role of grandparents as providers of food to their grandchildren. Appetite. 2019;134:78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.12.022. Cross-sectional study that assesses the extent to which grandparents are providing meals and snacks to their grandchildren, the types of foods and beverages being provided, and the determinants of provision. Grandparents were found to provide meals and snacks, with this food provision occurring several times per week.

McArthur LH, Fasczewski KS, Cook C, Martinez D. Snack-related practices, beliefs, and awareness of grandparent childcare providers: an exploratory study from three rural counties in North Carolina. USA Nutrire. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41110-021-00144-6.

Rhodes K, Chan F, Prichard I, Coveney J, Ward P, Wilson C. Intergenerational transmission of dietary behaviours: A qualitative study of Anglo-Australian, Chinese-Australian and Italian-Australian three-generation families. Appetite. 2016;103:309–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.04.036.

Shan LC, McCafferty C, Tatlow-Golden M, O’Rourke C, Mooney R, Livingstone MBE, et al. Is it still a real treat? Adults’ treat provision to children. Appetite. 2018;130:228–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.08.022.

O’Donohoe S, Gram M, Marchant C, Schänzel H, Kastarinen A. Healthy and indulgent food consumption practices within grandparent–grandchild identity bundles: a qualitative study of New Zealand and Danish families. J Fam Issues. 2021;42(12):2835–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X21992391.

Chambers SA, Dobbie F, Radley A, Rowa-Dewar N. Grandmothers’ care practices in areas of high deprivation of Scotland: the potential for health promotion. Health Promot Int. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab104.

Eli K, Hörnell A, Malek ME, Nowicka P. Water, juice, or soda? Mothers and grandmothers of preschoolers discuss the acceptability and accessibility of beverages. Appetite. 2017;112:133–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.011.

Criss S, Horhota M, Wiles K, Norton J, Hilaire KJS, Short MA, et al. Food cultures and aging: a qualitative study of grandparents’ food perceptions and influence of food choice on younger generations. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(2):221–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019002489.

Glover M, Wong SF, Taylor RW, Derraik JG, Fa’alili-Fidow J, Morton SM, et al. The complexity of food provisioning decisions by Māori caregivers to ensure the happiness and health of their children. Nutrients. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11050994.

Castañeda-García PJ, Luis-Díaz A, González-Rodríguez J, Gutiérrez-Barroso J. Exploring food and physical activities between grandparents and their grandchildren. UB J Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1344/ANPSIC2021.51/2.30536.

Eli K, Howell K, Fisher PA, Nowicka P. A question of balance: Explaining differences between parental and grandparental perspectives on preschoolers’ feeding and physical activity. Soc Sci Med. 2016;154:28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.030.

•• Pankhurst M, Mehta K, Matwiejczyk L, Moores CJ, Prichard I, Mortimer S, et al. Treats are a tool of the trade: An exploration of food treats among grandparents who provide informal childcare. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(14):2643–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019000685. Qualitative study that explores the meaning and role of food treats among grandparents providing regular informal care to their grandchildren. Food treats were found to play an important role in the grandparent–grandchild relationship. They were used as an educational tool, to express love, and for behavioural or emotional reasons.

•• Rogers E, Bell L, Mehta K. Exploring the role of grandparents in the feeding of grandchildren aged 1–5 years. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2019;51(3):300–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2018.08.016. Qualitative study that explores the views, beliefs, opinions, and motivations of grandparents in relation to grandchild feeding. Grandparents were required to navigate familial relationships while being responsible for their grandchildren. They regularly provided treats to their grandchildren.

Bektas G, Boelsma F, Gündüz M, Klaassen EN, Seidell JC, Wesdorp CL, et al. A qualitative study on the perspectives of Turkish mothers and grandmothers in the Netherlands regarding the influence of grandmothers on health related practices in the first 1000 days of a child’s life. BMC Public Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13768-8.

Knight A, O’Connell R, Brannen J. The temporality of food practices: intergenerational relations, childhood memories and mothers’ food practices in working families with young children. Fam Relatsh Soc. 2014;3(2):303–18. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674313X669720.

Neuman N, Eli K, Nowicka P. Feeding the extended family: gender, generation, and socioeconomic disadvantage in food provision to children. Food Cult Soc. 2019;22(1):45–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2018.1547066.

•• Marr C, Breeze P, Caton SJ. A comparison between parent and grandparent dietary provision, feeding styles and feeding practices when caring for preschool-aged children. Appetite. 2022;168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105777. Cross-sectional study comparing parent and grandparent dietary provision, feeding styles, and feeding practices. The only study to report on grandparents’ feeding styles, with ‘indulgent’ the most common.

•• Jongenelis MI, Morley B, Pratt IS, Talati Z. Diet quality in children: A function of grandparents’ feeding practices? Food Qual Prefer. 2020;83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103899. Cross-sectional study assessing grandparents’ feeding practices. The only study to explore the association between feeding practices and grandchild diet quality. Positive feeding practices were identified as being more important correlates of diet quality than negative feeding practices.

Farrow C. A comparison between the feeding practices of parents and grandparents. Eat Behav. 2014;15(3):339–42.

Hemar-Nicolas V, Ezan P, Gollety M, Guichard N, Leroy J. How do children learn eating practices? Beyond the nutritional information, the importance of social eating. Young Consumers. 2013;14(1):5–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473611311305458.

Metbulut AP, Özmert EN, Teksam O, Yurdakök K. A comparison between the feeding practices of parents and grandparents. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177:1785–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3244-5.

Jongenelis MI, Morley B, Worrall C, Talati Z. Grandparents’ perceptions of the barriers and strategies to providing their grandchildren with a healthy diet: A qualitative study. Appetite. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.105061.

Kim HS, Jiyoung PARK, Yumi MA, Mihae IM. What are the barriers at home and school to healthy eating?: overweight/obese child and parent perspectives. J Nurs Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000321.

• Lidgate ED, Li B, Lindenmeyer A. A qualitative insight into informal childcare and childhood obesity in children aged 0–5 years in the UK. BMC Public Health. 2018;18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6131-0. Qualitative study exploring informal childcare for children aged 0–5 years. Cross-generation conflict was found to prevent the adoption of healthy feeding practices.

Mena NZ, Gorman K, Dickin K, Greene G, Tovar A. Contextual and cultural influences on parental feeding practices and involvement in child care centers among Hispanic parents. Child Obes. 2015;11(4):347–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2014.0118.

Robinson A, Jongenelis MI, Morley B, Talati Z. Exploring grandparents’ receptivity to and preferences for a grandchild nutrition-focused intervention: A qualitative study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anzjph.2022.100001.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jongenelis, M.I., Budden, T. The Influence of Grandparents on Children’s Dietary Health: A Narrative Review. Curr Nutr Rep 12, 395–406 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-023-00483-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-023-00483-y