Abstract

We summarized existing evidence stemming from laboratory, clinical, and epidemiological studies regarding the differential association between low-fat or whole-fat dairy products and blood pressure control. We identified seven, large, prospective cohorts and one randomized trial that addressed the differential effect of low-fat versus whole-fat dairy products on blood pressure control or on the incidence of hypertension. An inverse association between low-fat dairy consumption and the risk of hypertension was found in most studies, whereas no risk reduction was observed for whole-fat dairy products. Several mechanisms might account for the blood-pressure-lowering effect of dairy products. The observed differential association may be attributable to the detrimental effect of saturated fat. In conclusion, low-fat dairy products but not whole-fat dairy products may contribute to improve blood pressure control and to reduce the incidence of hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension (high blood pressure) is considered the leading individual risk factor for death worldwide. Specifically, one billion people might be considered hypertensive and elevated blood pressure may be responsible for 7.6 million deaths a year. Besides, hypertension is the second more important contributor to disability adjusted life years lost [1]. Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, presenting a continuous, consistent, and independent association with a number of cardiovascular outcomes. Therefore, approaches to prevent this condition are an urgent need.

It is generally accepted that lifestyle factors, such as physical activity and body weight control, are key for the prevention of hypertension. In addition, a healthy dietary pattern rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products and low in saturated fat has been consistently associated with a lower incidence of hypertension [2–4]. In the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010, consumption of 3 cups per day of fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products is recommended as part of a healthy diet [5]. Fat-free and low-fat dairy products are recommended instead of whole-fat dairy products due to a smaller caloric content.

Dairy products are a good source of potentially beneficial nutrients, such as magnesium, potassium, calcium, and bioactive peptides. Different studies have suggested that dairy products might be associated with lower blood pressure and reduced risk of hypertension. This topic has been the focus of a recently published review [6••]. Despite the beneficial nutrient profile of dairy products, they also contribute to fat intake. The main type of fat in dairy products is saturated fat, specifically palmitic acid. Based on their fat content, dairy products can be classified as low-fat or whole-fat dairy products. Because the amount of saturated fat in dairy products might influence their effects on health outcomes, we reviewed the published literature to assess the differential role of whole-fat versus low-fat dairy products on blood pressure levels or the incidence of hypertension. We first provide a summary of the epidemiological evidence on the association of dairy products with hypertension and blood pressure, and then we discuss the physiological mechanisms that could explain the observed associations.

Epidemiological Evidence

In the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) [3, 4, 7] randomized trial, three diets were compared in 459 participants for an 8-week period. A diet rich in fruits and vegetables achieved better results in lowering blood pressure levels than a typical American control diet. The best results were obtained with the so-called combination diet, which is known as the DASH diet [4, 7]. A high consumption of low-fat dairy products (2 servings/day of low-fat dairy products in the combination diet) was one of the key components of the DASH diet compared with the diet rich in fruits and vegetables (0 servings/day of low-fat dairy products). It has been estimated that the DASH diet together with a sodium restriction down to 1,600 mg could be as effective as any conventional antihypertensive treatment [8]. Similar results were obtained in nonrandomized, prospective cohort studies that assessed the association between adherence to the DASH diet and the incidence of hypertension [2, 9, 10].

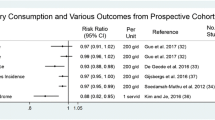

Table 1 describes cohort studies assessing the differential effects of low-fat versus whole-fat dairy products on blood pressure control or on the incidence of hypertension.

Cohort Studies

Results from observational cohort studies evaluating the differential association between low-fat and whole-fat dairy products are summarized in Table 2. An overall assessment of these studies has to account for the heterogeneity in the methods used to assess dairy food consumption, blood pressure, and hypertension ascertainment.

In the Nurses´ Health Study, differences in systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels across quintiles of high-fat or low-fat dairy products after four years of follow-up were ascertained [11]. No statistically significant differences were observed.

In the SUN cohort, a prospective study of university graduates in Spain, consumption of low-dairy products was inversely associated with the incidence of hypertension after a median follow up of 2.3 years. This effect was not observed for the consumption of whole-fat dairy products [12]. In this cohort, dietary calcium from low-fat dairy products (but not from whole-fat dairy foods) was inversely associated with the incidence of hypertension.

These differential results for low-fat dairy versus whole-fat dairy were confirmed in the Women’s Health Study, a cohort involving more than 28,000 women older than age 45 years [13]. For low-fat dairy products, a significant inverse association with hypertension was observed, whereas no significant association between whole-fat dairy products and incident hypertension was seen.

The association between dairy intake and incident hypertension also was assessed in 2,245 Rotterdam Study participants who were free of hypertension at baseline (1990–1993) and were followed for 6 years. Analyses of specific types of dairy products showed an inverse association with milk and milk products (p for trend = 0.07) and no association with high fat dairy or cheese (p for trend > 0.6) [14].

Similar associations were explored in a Dutch cohort of 3,454 middle-aged participants with a follow-up time of 5 years. Higher intake of low-fat dairy products was associated with a nonsignificant lower risk of incident hypertension. On the other hand, a nonsignificant direct association between whole-fat dairy products and incident hypertension was found [15].

In the PREDIMED study, after a 12-month follow-up of an elderly population at high cardiovascular risk, low-fat dairy product consumption was inversely associated with blood pressure levels [16]. Contrarily, no statistically significant association for whole-fat dairy products was found. Consistently with the PREDIMED results, the ARIC study reported an inverse association between low-fat milk and mean changes in systolic blood pressure during 9 years of follow-up. Again, in this latter study no significant association was observed for whole-fat milk [17].

Randomized Trials

To date, only one randomized trial has specifically assessed the differential effect of low-fat versus whole-fat dairy products on blood pressure levels. This small crossover trial was conducted in 45 normotensive volunteers aged 18-24 years who were supplied with 3.5 servings/day of low-fat or whole-fat dairy products. Blood pressure was measured at the beginning and end of each intervention period. Whole-fat dairy intake significantly increased systolic blood pressure (SBP) and body weight but not diastolic blood pressure (DBP) after 8 weeks of intervention. Low-fat dairy, on the other hand, did not change blood pressure or body weight significantly after 8 weeks of intervention. However, no statistically significant difference was found between both interventions (Table 2) [18••].

Physiological Mechanisms

In observational studies, participants with a higher consumption of low-fat dairy products tend to have a healthier overall lifestyle and a healthier dietary pattern. Although the aforementioned inverse association between low-fat dairy products and hypertension (or blood pressure changes) might be partially explained by residual confounding, the available cohorts extensively controlled for potential confounding and the inverse association between low-fat dairy products and hypertension remained significant. Moreover, the causal interpretation is supported by different biological mechanisms that provide a likely biological plausibility to the observed association.

Different nutrients present in dairy products could explain a beneficial effect of these foods on blood pressure levels and on a reduced incidence of hypertension, including calcium, vitamin D, magnesium, potassium, and bioactive dairy peptides. The differential content in fatty acids between low-fat and whole-fat dairy products may help to explain the distinct association between the two types of dairy products observed in epidemiological studies.

Calcium and Vitamin D

Dairy products are the most important source of dietary calcium. It has been suggested that dietary calcium may influence blood pressure. On the one hand, ionic calcium may reduce blood pressure levels centrally [19]. On the other hand, concerning ionic calcium peripheral action, the rise in plasmatic calcium concentrations may increase blood pressure by enhancing smooth muscle contractility [19]. Calcium channel blockers, used in the treatment of hypertensive patients, block the peripheral mechanism and their action may be enhanced if a high calcium intake could maintain calcium blood levels in the upper limits within normality to preserve the central hypotensive effect [19].

Beside this, a diet rich in calcium could increase urinary sodium excretion may limit the effect of desoxicorticosterone on sodium balance, improve vascular smooth muscle relaxation and tone down its contractility, increase the sensitivity to nitric oxide in arterial smooth muscle cells, and decrease the production of superoxide anions and vasoconstrictor prostaglandins [20]. Furthermore, high levels of calcium intake may inhibit the production of parathyroid hormone and vitamin D synthesis, which increases intracellular calcium concentrations and thus vascular smooth muscle cell contraction [20]. Despite the high calcium contents of dairy products, it has been observed that diets richer in dairy products have beneficial effects on intracellular calcium concentrations [21]. Nevertheless, a meta-analysis on the potentially beneficial effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure concluded that the evidence for a blood–pressure-lowering effect of calcium supplementation in subjects with raised blood pressure was not robust and, given the scarcity of available evidence and the potential for bias, better studies are needed [22]. Furthermore, a large trial found no significant effect of calcium intake and vitamin D3 supplementation (1,000 mg of elemental calcium plus 400 IU of vitamin D3 per day) on blood pressure [23]. Interestingly, in the Women’s Health Initiative [13], an inverse association between dietary calcium and dietary vitamin D and incident hypertension was observed after a mean follow-up of 7.0 years, whereas no significant associations were seen for calcium of vitamin D supplements, suggesting that effects of dietary micronutrients and micronutrient supplements may be different. In the SUN Project prospective cohort [12], however, only dietary calcium from low-fat dairy products was associated inversely with the risk of hypertension. Thus, in this latter study, dietary calcium was a proxy for low-fat dairy consumption.

Magnesium

Dairy products are a good source of magnesium, which is a mineral capable of inhibiting smooth muscle contraction and which therefore has an important vasodilator action [20]. A meta-analysis of randomized trials assessing the association between magnesium supplementation with blood pressure found an inverse dose-dependent association between the supplementation with magnesium and changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure [24]. Nonetheless, another systematic review concluded that the evidence supporting a beneficial effect of magnesium supplements on blood pressure was weak and likely biased [25].

Phosphorus

Evidence from cross-sectional studies suggests an inverse association between phosphorus intake and blood pressure [26]. Nevertheless, when this association was tested with a longitudinal design, the association was attenuated after adjustment for other dietary factors. What is more important, this association was only present for dietary phosphorus from dairy products origin, suggesting that dairy products rather than phosphorus could be responsible for this association [27].

Potassium

Dairy products contribute to lower blood pressure levels probably not only because they are rich in calcium and magnesium but because they are also rich in potassium. Potassium is able to decrease blood pressure levels through different pathways. Acting on the kidney, it facilitates natriuresis, diminishes calcium excretion, and is protective against renal vascular, glomerular, and tubular lesions [28, 29]. Likewise, potassium affects the regulation of the central sympathetic nervous system tempering the hypothalamic and renal turnover of noradrenaline [30] and toning down the blood pressuring response to noradrenaline and angiotensine II. Potassium also acts on the endothelium by hyperpolarization, by increasing the sensitivity to nitric oxide, by decreasing the synthesis of vasoconstricting prostaglandins [28] and by inhibiting smooth muscle contraction [20]. Potassium supplementation has been associated with improved endothelial function, increased arterial compliance, decreased left ventricular mass and improved left ventricular diastolic function [31]. In the DASH trial, a decrease in blood pressure was observed with potassium-rich diets [4]. However, the effect of dietary potassium seems different than the effect of potassium supplements. In a meta-analysis of six, randomized, controlled trials, no effect of potassium supplements on blood pressure was observed among participants with raised blood pressure [32].

Dairy Bioactive Peptides

In addition to the forenamed micronutrients, milk contains a wide variety of peptides that may exert biological effects. Some of these are able to bind bivalent cations, such as calcium and magnesium, modifying their bioavailability if they are consumed as dietary supplement or in milk [33]. Besides the aforementioned peptides, milk also contains lactose, citrates, proteins, and peptides that may increase the bioavailability of magnesium, manganese, zinc, selenium, copper, and iron [33].

Dairy products also could exert a blood–pressure-lowering effect through inhibition of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). ACE enhances angiotensin, which is synthesised in response to renin, produces a quick arteriolar and, to a lesser extent, venous contraction and, in the long-term, decreases renal sodium and water excretion acting either directly on the kidney or indirectly by the release of aldosterone [20]. ACE also inhibits bradikinin, a kinin synthesised from plasmatic or tissular alfa-2 globulins by proteolitic enzymes, which has arteriolar vasodilating effect and increases capilar permeability [20, 34]. In addition, endotheline is a peptide released by the endothelium, which has a strong vasoconstricting effect [17]. The specific inhibition of its receptor decreases blood pressure [35]. If ACE activity is inhibited, intracellular bradikinins concentration increase, inhibiting thereby endothelin-1 release [36]. The digestion of milk proteins by gastrointestinal, bacterial, or vegetable proteases releases peptides, many of which inhibit ACE and endothelin release. Casokinins and lactokinins are ACEI proteins (natural ACEIs) stemming from dairy casein and whey, respectively [37, 38]. These peptides are not as powerful as ACEI drugs, but these natural substances could have beneficial effects on hypertension prevention or treatment without having side effects [34, 39]. Furthermore, results from available trials assessing the effect of two dairy tripeptides, isoleucine-proline-proline and valine-proline-proline, have been presented in several systematic reviews and metanalyses [40–42, 43•]. Significant decreases of −3.73 mmHg (95 % confidence interval, −6.7, −1.76) in systolic blood pressure (BP) and −1.97 mmHg (95 % confidence interval, −3.85, −2.44) in diastolic blood pressure for lactotripeptides when compared to placebo were found. Finally, the lactokinin Ala-Leu-Pro-Met-His-Ile-Arg (ALPMHIR) derived from dairy products has shown to be able to inhibit endothelin-1 release [44].

In addition, other dairy peptides have shown agonistic activity over opioid receptors. Therefore, dairy products also could modify blood pressure through this pathway [45].

Fat contents

The difference between whole-fat and low-fat dairy products is their amount of fat, which may explain the differences observed in epidemiologic studies between whole-fat and low-fat dairy products. Palmitic acid is the main type of fatty acid in dairy products. Culture of endothelial cells in the presence of palmitic acid inhibits the production of nitric oxide in a dose-response trend [46]. Endothelium-dependent vasodilatation can be measured after the stimulation with methacholin (methacholine stimulates nitric oxide-synthase), whereas endothelium-independent vasodilatation can be measured after the stimulation with sodium nitroprussate. With these two parameters, an index of endothelial function can be defined as the quotient between the endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and the endothelium-independent vasodilatation. This quotient will show the activity of the nitric oxide synthase in relation to total vasodilatation.

Palmitoleic acid can be produced in the metabolism of palmitic acid. Higher levels of palmitoleic acid have been associated with worse endothelial function and, therefore, a higher exposure to palmitoleic acid is expected to be associated with higher blood pressure levels [47]. In a recent cross-sectional study, the intake of whole-fat dairy was positively and independently associated to soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, whereas the intake of low-fat dairy products showed an inverse independent association [48].

Plasmatic levels of several fatty acids are related to dietary fatty acid intake. In a cohort study with a follow-up time of 6 years [49], higher plasmatic levels of palmitic and palmitoleic acids were associated with a higher risk of hypertension. Considering palmitic acid, the association disappeared once baseline systolic blood pressure was adjusted for. Besides this, an elevated ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acid ratio was protective against the incidence of hypertension. Taking into account that whole-fat dairy products are an important source of saturated fatty acids, and also that palmitic acid is the main fatty acid in dairy products and that palmitic acid can be metabolized to palmitoleic acid, the lipid profile of whole-fat dairy products can be detrimental for blood pressure and thus it might counteract other potentially beneficial effects of other nutrients available in dairy products. However, these results should be interpreted cautiously, because plasmatic levels of palmitic acid are derived not only from diet but also form the novo synthesis.

Conclusions

Not only epidemiological and laboratory evidence but also biological plausibility suggest that a differential effect is very likely for whole-fat versus low-fat dairy products on blood pressure control. Thus, the consumption of low-fat dairy products could be promoted as a tool to tackle the impact of elevated blood pressure in the population. Nevertheless, further evidence from large, randomized trials on this issue is required.

References

Papers of published papers of interest have been highlighted as: • Of Importance •• Of Major Importance

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–57.

Toledo E, Carmona-Torre FA, Alonso A, et al. Hypothesis-oriented food patterns and incidence of hypertension: 6-year follow-up of the SUN (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra) prospective cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(3):338–49.

Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(1):3–10.

Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1117–24.

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. Washington, DC; 2010.

•• McGrane MM, Essery E, Obbagy J, et al. Dairy consumption, blood pressure, and risk of hypertension: an evidence-based review of recent literature. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2011;5(4):287–98. A recently published review that covers the topic on dairy consumptio, blood pressure and incident hypertension.

Svetkey LP, Simons-Morton D, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure: subgroup analysis of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(3):285–93.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–72.

Schulze MB, Hoffmann K, Kroke A, Boeing H. Risk of hypertension among women in the EPIC-Potsdam Study: comparison of relative risk estimates for exploratory and hypothesis-oriented dietary patterns. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(4):365–73.

Dauchet L, Kesse-Guyot E, Czernichow S, et al. Dietary patterns and blood pressure change over 5-y follow-up in the SU.VI.MAX cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(6):1650–6.

Ascherio A, Hennekens C, Willett WC, et al. Prospective study of nutritional factors, blood pressure, and hypertension among US women. Hypertension. 1996;27(5):1065–72.

Alonso A, Beunza JJ, Delgado-Rodriguez M, et al. Low-fat dairy consumption and reduced risk of hypertension: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(5):972–9.

Wang L, Manson JE, Buring JE, et al. Dietary intake of dairy products, calcium, and vitamin D and the risk of hypertension in middle-aged and older women. Hypertension. 2008;51(4):1073–9.

Engberink MF, Hendriksen MA, Schouten EG, et al. Inverse association between dairy intake and hypertension: the Rotterdam Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(6):1877–83.

Engberink MF, Geleijnse JM, de Jong N, et al. Dairy intake, blood pressure, and incident hypertension in a general Dutch population. J Nutr. 2009;139(3):582–7.

Toledo E, Delgado-Rodriguez M, Estruch R, et al. Low-fat dairy products and blood pressure: follow-up of 2290 older persons at high cardiovascular risk participating in the PREDIMED study. Br J Nutr. 2009;101(1):59–67.

Alonso A, Steffen LM, Folsom AR. Dairy intake and changes in blood pressure over 9 years: the ARIC study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63(10):1272–5.

•• Alonso A, Zozaya C, Vazquez Z, et al. The effect of low-fat versus whole-fat dairy product intake on blood pressure and weight in young normotensive adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2009;22(4):336–42. The only randomized controled trial assessing the differential effect of low-fat and whole-fat dairy products on blood pressure.

Sutoo D, Akiyama K. Regulation of blood pressure with calcium-dependent dopamine synthesizing system in the brain and its related phenomena. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;25(1):1–26.

Guyton AC, Hall JE. Textbook of medical physiology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Sauders; 2005.

Hilpert KF, West SG, Bagshaw DM, et al. Effects of dairy products on intracellular calcium and blood pressure in adults with essential hypertension. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28(2):142–9.

Dickinson HO, Nicolson DJ, Cook JV, et al., Calcium supplementation for the management of primary hypertension in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD004639.

Margolis KL, Ray RM, Van Horn L, et al. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on blood pressure: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Trial. Hypertension. 2008;52(5):847–55.

Jee SH, Miller 3rd ER, Guallar E, et al. The effect of magnesium supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15(8):691–6.

Dickinson HO, Nicolson DJ, Campbell F, et al. Magnesium supplementation for the management of essential hypertension in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD004640.

Elliott P, Kesteloot H, Appel LJ, et al. Dietary phosphorus and blood pressure: international study of macro- and micro-nutrients and blood pressure. Hypertension. 2008;51(3):669–75.

Alonso A, Nettleton JA, Ix JH, et al. Dietary phosphorus, blood pressure, and incidence of hypertension in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study and the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2010;55(3):776–84.

Vaskonen T. Dietary minerals and modification of cardiovascular risk factors. J Nutr Biochem. 2003;14(9):492–506.

Tobian L, MacNeill D, Johnson MA, et al. Potassium protection against lesions of the renal tubules, arteries, and glomeruli and nephron loss in salt-loaded hypertensive Dahl S rats. Hypertension. 1984;6(2 Pt 2):I170–6.

Fujita T, Sato Y. Role of hypothalamic-renal noradrenergic systems in hypotensive action of potassium. Hypertension. 1992;20(4):466–72.

He FJ, Marciniak M, Carney C, et al. Effects of potassium chloride and potassium bicarbonate on endothelial function, cardiovascular risk factors, and bone turnover in mild hypertensives. Hypertension. 2010;55(3):681–8.

Dickinson HO, Nicolson DJ, Campbell F, et al. Potassium supplementation for the management of primary hypertension in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD004641.

Vegarud GE, Langsrud T, Svenning C. Mineral-binding milk proteins and peptides; occurrence, biochemical and technological characteristics. Br J Nutr. 2000;84 Suppl 1:S91–8.

FitzGerald RJ, Murray BA, Walsh DJ. Hypotensive peptides from milk proteins. J Nutr. 2004;134(4):980S–8.

Krum H, Viskoper RJ, Lacourciere Y, et al. The effect of an endothelin-receptor antagonist, bosentan, on blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension. Bosentan Hypertension Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(12):784–90.

Momose N, Fukuo K, Morimoto S, Ogihara T. Captopril inhibits endothelin-1 secretion from endothelial cells through bradykinin. Hypertension. 1993;21(6 Pt 2):921–4.

Meisel H. Casokinins as inhibitors of angiotensin-I-converting enzyme. In: Sawatsky G, Renner B, editors. New perspectives in infant nutrition. New York: Thieme; 1993.

FitzGerald RJ, Meisel H. Lactokinins: whey protein-derived ACE inhibitory peptides. Nahrung. 1999;43(3):165–7.

FitzGerald RJ, Meisel H. Milk protein-derived peptide inhibitors of angiotensin-I-converting enzyme. Br J Nutr. 2000;84 Suppl 1:S33–7.

Xu JY, Qin LQ, Wang PY, et al. Effect of milk tripeptides on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition. 2008;24(10):933–40.

Pripp AH, Effect of peptides derived from food proteins on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Nutr Res. 2008;52.

Geleijnse JM, Engberink MF. Lactopeptides and human blood pressure. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21(1):58–63.

• Cicero AF, Gerocarni B, Laghi L, Borghi C. Blood pressure lowering effect of lactotripeptides assumed as functional foods: a meta-analysis of current available clinical trials. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25(7):425–36. A recently published metanalysis on the effects of lactotripeptides Valine-Proline-Pronline and Isoleucine-Proline-Proline on blood pressure levels.

Maes W, Van Camp J, Vermeirssen V, et al. Influence of the lactokinin Ala-Leu-Pro-Met-His-Ile-Arg (ALPMHIR) on the release of endothelin-1 by endothelial cells. Regul Pept. 2004;118(1–2):105–9.

Jauhiainen T, Korpela R. Milk peptides and blood pressure. J Nutr. 2007;137(3 Suppl 2):825S–9.

Moers A, Schrezenmeir J. Palmitic acid but not stearic acid inhibits NO-production in endothelial cells. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1997;105 Suppl 2:78–80.

Sarabi M, Vessby B, Millgard J, Lind L. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation is related to the fatty acid composition of serum lipids in healthy subjects. Atherosclerosis. 2001;156(2):349–55.

Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L. Dairy consumption and circulating levels of inflammatory markers among Iranian women. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(9):1395–402.

Zheng ZJ, Folsom AR, Ma J, et al. Plasma fatty acid composition and 6-year incidence of hypertension in middle-aged adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(5):492–500.

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Health (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias project PI070240; RD 06/0045). ET is supported by a Rio Hortega post-residency fellowship of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Spanish Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

All authors contributed substantially to this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toledo, E., Alonso, Á. & Martínez-González, M.Á. Differential Association of Low-Fat and Whole-Fat Dairy Products with Blood Pressure and Incidence of Hypertension. Curr Nutr Rep 1, 197–204 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-012-0026-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-012-0026-y