Abstract

Background

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by non-scarring hair loss in adults and children. Clinical manifestations range from hair loss in small, well-circumscribed patches to total hair loss on the scalp or any other hair-bearing areas. Although the exact pathogenesis of AA is not fully understood, it is thought that loss of immune privilege caused by immunological dysregulation of the hair follicle is key. Genetic susceptibility also plays a role. Response to currently available treatments is widely variable, causing patient dissatisfaction and creating an unmet need. AA is frequently associated with multiple comorbidities, further affecting patient quality of life.

Aims and Findings

AA causes a significant burden on dermatologists and healthcare systems in the Middle East and Africa. There is a lack of data registries, local consensus, and treatment guidelines in the region. Limited public awareness, availability of treatments, and patient support need to be addressed to improve disease management in the region. A literature review was conducted to identify relevant publications and highlight regional data on prevalence rates, diagnosis, quality of life, treatment modalities, and unmet needs for AA in the Middle East and Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is a lack of awareness, national registries, and consistent treatment access for alopecia areata (AA) in the region. |

This review identifies relevant publications to highlight data on prevalence rates, quality of life, and treatment modalities for AA in the Middle East and Africa. |

The lack of regional guidelines has led to non-uniform treatment plans among dermatologists. |

International guidelines on AA management should be leveraged while developing regional consensus and establishing patient support programs in the region. |

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by non-scarring hair loss in well-circumscribed patches [1, 2]. AA can lead to considerable disfigurement and psychosocial distress and is currently reported as the most prevalent autoimmune disease associated with reduced quality of life (QoL) [1, 3]. AA affects both adults and children, occurs at similar rates in men and women, and has an average onset at 20–25 years [1, 4]. The general lifetime incidence of AA is approximately 2% in adults. First-degree relatives are at a 24% increased risk of being affected. It is the third most common dermatologic presentation in children, with a lifetime risk of 1–2% [1, 4, 5]. AA may also be associated with other autoimmune diseases such as vitiligo, psoriasis, thyroid diseases, type 1 diabetes mellitus, atopic dermatitis, celiac disease, and lupus erythematosus [6,7,8]. AA has an unpredictable disease course. Spontaneous hair regrowth can occur within the first year with or without treatment and sudden relapse may occur at any time [9]. Several hypotheses regarding the etiopathogenesis of AA suggest a possible role of viral and bacterial infections, endocrine, autoimmune, psychological, viral, and genetic factors [1, 4].

A study by Fricke et al. (2015) reported a variation in disease incidence worldwide from 2.1% and 0.7% to 3.8% in the USA, India, and Singapore, respectively [3]. In Africa and the Middle East, regional studies have reported a disease prevalence ranging between 0.2% and 13.8% on the basis of the individual treatment landscape of the countries [10].

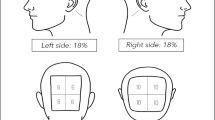

The diagnosis of AA is usually based on history taking and clinical examination; skin biopsies are rarely required. The Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) is an assessment tool to measure the disease extent in the scalp. SALT scores range from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating no scalp hair loss and 100 indicating complete hair loss on the scalp. It is primarily used in clinical trials studying the response to AA treatments [11].

Despite the advances in new treatment protocols, standardized AA treatment is lacking. Many therapies currently used in clinical practice to induce hair regrowth are not validated by clinical trials. None of these therapies are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are used off-label. A variety of topical, intralesional, systemic, and device treatments exist for the management of AA. Topical, intralesional, and oral steroids remain popular treatments. Other topical treatments include topical immunotherapies such as squaric acid dibutyl ester and diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP). Systemic immunosuppressants include cyclosporin, azathioprine, and methotrexate. Additionally, topical or systemic minoxidil has been prescribed as adjuvant therapy by some dermatologists. Recent off-label procedural treatment modalities include microneedling, platelet-rich plasma, laser, and stem cell therapy [12,13,14,15]. In 2022, the FDA approved the use of baricitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi) for adults with severe AA. Currently, baricitinib is the only treatment for AA that has undergone two phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trials; BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2. These trials reported an 80% hair regrowth efficacy over 36 weeks for patients treated with baricitinib, proving its efficacy over placebo [16].

There is a lack of established registries, robust epidemiological data, and standardized management guidelines for AA in Africa and the Middle East. This is reflected in the region’s high disease burden and unmet needs for patients with AA. Through this manuscript, we attempt to gain insights into the regional data for AA, focusing on etiopathogenesis, prevalence, and disease burden as measured by disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and QoL. We also report the psychosocial and economic impact of AA in the region. Finally, we highlight the treatment approaches used in different countries of Africa and the Middle East by analyzing scoring systems, clinician decisions, drug availability, and patient compliance.

Methods

A literature search was conducted via PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science databases. The following search strings were used: (“alopecia areata” AND (“North Africa” OR “Middle East” OR “South Africa”)). Individual country names in the region combined with keywords such as “alopecia”, “hair loss”, “trichoscopy”, and “epidemiology” were also used. The geographical areas of interest were composed of the countries of the Middle East and Africa, including the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Jordan, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Bahrain, Tunisia, Kuwait, Lebanon, and South Africa. Studies published in English between 2010 and 2021 were selected for data extraction. The extracted data were reorganized into the tables presented. Statistical analyses were not feasible due to the heterogeneity of parameters reported in the various studies. To define the epidemiology of AA, articles with data on the prevalence, incidence, and distribution by sex or age were selected. Articles with data on DALYs and associated psychiatric or medical comorbidities were included to assess the disease burden. During the development of this review, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 checklist was consulted as a guide; however, not all checklist items were strictly adhered to. The authors declare ethical compliance as this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Outcomes of Literature Search Strategy

The PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science databases were searched for relevant publications. Articles were initially screened by title and abstract according to the following exclusion criteria: abstract-only articles, studies not involving primary data collection, non-clinical studies, and irrelevant study design or outcome assessments. After duplicates were removed, 112 articles were screened via full-text assessment, and 18 were excluded as they were either irrelevant (based on patient population or intervention) or had insufficient subgroup data analysis. In total, 94 publications were selected for the scope of this review.

Results

Etiology and Pathophysiology

AA is a form of non-scarring alopecia that occurs in a patchy, confluent, or diffuse patterns. It may occur as a single, self-limiting episode or recur at varying intervals over the years. The etiology of AA is not fully understood. However, factors that appear to be implicated in etiopathogenesis are the patient’s genetic constitution, atopic state, nonspecific immune and organ-specific autoimmune reactions, and emotional stress [17].

Proinflammatory signals such as substance P, interferon-γ, and reactive oxygen species upregulate the expression of major histocompatibility complex class IA, causing a breakdown of the immune-privileged sites in anagen hair follicles. This subsequently triggers a CD8+-driven, Th1-type T-cell autoimmune reaction against anagen hair follicles, resulting in acute hair loss of the growing hair shaft [1, 9].

The onset of AA is typically before the age of 40 years in 70–80% of patients; a substantial proportion of ~ 48% will show clinical signs during their first and second decades, making AA a common cause of hair loss in adolescents and children. Early onset of AA is an important negative prognostic factor frequently overlooked by family members and dermatologists in the early stages. It is associated with a high relapse rate and traditional treatment failure, which can significantly impact a patient’s QoL [18, 19].

Clinical Variants and Signs

The clinical presentation of AA varies depending on the location of lesions and the extent of hair loss. AA can be classified as patchy AA with localized areas of hair loss; ophiasis, which appears as band-like confluent patches in the occipital and temporal regions of the scalp; sisaipho, which occurs as central hair loss in the areas not affected by the ophiasis variant, usually sparing the temporal and occipital regions; alopecia totalis (AT), affecting the entire scalp; and alopecia universalis (AU), affecting the scalp and all body hair [4].

The typical clinical signs of AA include waxing and waning patches of smooth, circular discrete areas of completed hair loss, most commonly on the scalp, but may involve any hair-bearing area such as the eyebrows, eyelashes, beard, or extremities. Dermatoscopic features include yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, tapering or exclamation point hairs, and short vellus hairs at the margins. Nails may be involved and display fine-stippled pitting; occasionally nail dystrophy can manifest. A characteristic that may be shared by all types of AA is sporadic regrowth of hair in one area of the scalp, which is associated with the appearance of new patches or the expansion of existing patches elsewhere [4, 20].

AA Scale for Diagnosis

In addition to the SALT scoring system, the AA disease severity scale was developed following consensus by an expert panel of 22 board-certified dermatologists from the USA. It was designed to address the unmet need for a scoring system that adequately characterized the clinical spectrum of AA severity and considered eyebrow and eyelash involvement, treatment-refractory disease, and psychosocial impact. It uses the extent of scalp hair loss as the primary basis for a severity rating, in addition to four secondary clinical features, including psychosocial functioning, involvement of eyebrows or eyelashes, inadequate treatment response, and diffuse positive hair pull test. The scores are calculated as mild: 20% or less scalp hair loss; moderate: 21–49% scalp hair loss; and severe: 50–100% scalp hair loss [21, 22].

Prevalence

Global Data

AA affects approximately 2% of the general population, as documented by several epidemiological studies from Europe, North America, and Asia [3]. A study by Lee et al. [23] evaluated the epidemiological data on the global prevalence of different clinical variants of AA and reported an overall prevalence of 1.9% in children [23].

Africa and the Middle East

Table 1 presents the results of AA prevalence studies conducted in Africa and the Middle East.

Disease Burden

Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)

The burden of AA has been measured by DALYs, which combines years lost to disability, including morbidity, and years lost to death, such that 1 DALY represents 1 year of healthy life lost [3].

In the Global Burden of Disease study, the World Health Organization (WHO) measured the global DALYs lost to AA in 2010 to be 1,332,800. The DALYs for AA have been increasing linearly since 1990. A possible limitation of this study was an underestimation of the true population-based prevalence [3]. Another epidemiological study by Karimkhani et al. (2014) reported that AA is often underrepresented during literature searches in databases such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews when matched with corresponding DALYs for other common skin diseases [30].

A retrospective survey by Wang et al. [31] reported that in 2019, Central Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa were regions with among the lowest age-standardized DALY rates for AA patients (6.70 and 6.26, respectively) [31].

Health-Related QoL

It has been estimated that over half of the patients with AA experience deterioration in their QoL. Female gender, change in physical appearance, family stress, increased prevalence of mood disorders, and impairment of social life are contributing factors [3, 32]. Several dermatology-specific questionnaires have been developed to evaluate the impact of AA on QoL, especially in the area of mental health. These include Skindex, Dermatology Life Quality Index, dermatology QoL scales, and dermatology categorical QoL scales [33]. Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 describe the results of a literature search for studies conducted in Africa and the Middle East to assess the extent of this impairment caused by AA.

Psychiatric Morbidity and Social Impact

Studies have shown that despite stress having a minor influence on the initial onset of AA, the condition can affect stress mediators and psychoneuroimmunology pathways, resulting in progressive distress and depression. Additionally, individuals with AA may exhibit elevated hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity, which impairs their capacity to adjust to stress-related mediators [41]. A study by Sellami et al. [42] in Tunisian patients aimed to investigate the possible relationship between AA, anxiety, depression, and alexithymia. The results showed a higher prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in AA patients when compared with controls. This was due to low self-esteem and social isolation. In addition, a high prevalence of alexithymia was observed in these patients, affecting their ability to form emotional attachments and maintain an active social life [42, 43]. As a result of the physical disfigurement caused by the disease, pediatric patients are often subjected to social isolation and bullying by peers at school, which severely impacts their QoL.

There are no available large-scale regional studies from Africa and the Middle East evaluating the correlation of AA with psychiatric disorders.

Comorbid Medical Conditions

AA has been associated with atopic diseases such as asthma, hypothyroidism, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, vitiligo, celiac disease, and lupus erythematosus [6].

In a study by Bakry et al. [44] on a cohort of Egyptian patients, hypothyroidism was found in 16% of AA patients. Patients had lower levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, free T3 and T4 hormones, as well as a positive assay for the thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin antibodies. The investigators proposed screening all patients with AA for thyroid function abnormalities, even in the absence of clinical signs of hypothyroidism, for the early detection of subclinical thyroid abnormalities [44]. A similar study by Arousse et al. (2019) in Tunisian patients reported the occurrence of atopic disease in 18.1% of patients with AA, whereas hypothyroidism was noted in 12.7% of the patients [11]. Another study by Saif et al. (2016) in Saudi patients reported higher frequencies of thyroid autoantibodies and thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin antibodies in patients with AT and AU when compared with those with mild AA [45].

A study by Alamoudi et al. [46] in Saudi patients reported that hypothyroidism was the most common medical comorbidity in patients with AA, followed by atopic diseases, diabetes, and mood disorders. Most of these comorbidities were identified in patients with a patchy type of AA [46]. Similar results were reported by Alshahrani et al. (2020), reporting comorbidities, including hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, and atopic diseases, in 32.4% of patients with AA [4].

A retrospective study by Hasan et al. [47] reported that a pediatric patient cohort from Bahrain had a higher risk of developing celiac disease, which can be attributed to common cell-mediated autoimmune mechanisms as the underlying etiopathogenesis [47].

Another interesting study by Marie et al. (2020) in Egyptian patients reported significantly elevated levels of cardiac troponin I and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide biomarkers in patients with AA compared with controls. The study suggested a possible association of AA with myocardial inflammation and an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease [48].

Economic Impact

Many patients with extensive AA, AT, and AU can be dissatisfied with current medical treatments and resort to alternative management resources such as wigs, hairpieces, powders, eyebrow tattoos, or other camouflage modalities. The accumulation of expenses of these alternative resources, in addition to insurance premiums, copayments, deductibles, and lost income, is financially burdensome. Despite the lack of data on the financial impact and reimbursement challenges that patients face in the Middle East, dermatologists are encouraged to be aware of the potential ramifications of treatment costs for patients and consider financial impairment when suggesting treatments. Government-sponsored plans should be implemented to address these issues [49].

Treatment Options

Although the approval of JAKi is a valuable addition to the armamentarium of treatment options for adult patients with severe AA, available options for pediatric and adolescent populations are insufficient [13, 50]. AA management is challenging, especially in Africa and the Middle East, where treatment plans have no region-specific guidelines [51, 52]. Tables 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 provide an overview of selected studies conducted in the region to treat patients with AA.

One of the main issues dermatologists face in the absence of region-specific recommendations is the lack of uniformity in treatment regimens. The identified studies highlight this clinical practice gap, making it challenging to compare the efficacies of different treatment modalities.

Guideline Recommendations

There is a lack of local evidence-based guidelines, protocols, or algorithms for the management of AA in Africa and the Middle East. Most local dermatologists follow international guidelines, namely the British [87], Italian [88], German [89], and American guidelines [90].

This section will attempt to provide an overview of some key consensus statements issued by global expert panels that aim to guide future regional AA management guidelines.

International Consensus Statements on AA Treatment

Meah et al. (2020) conducted a comprehensive study to compile a first-of-its-kind consensus on the expert age-wise assessment of AA treatment. A total of 50 hair experts from five continents participated in a three-round Delphi process that included questions regarding the epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, investigation, treatment, and prognosis of AA. An agreement of ≥ 66% was considered a consensus to formulate the Alopecia Areata Consensus of Experts (ACE) guidelines, which are now widely used by dermatologists in clinical practice. These statements are summarized below [91].

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are the first line of treatment in children < 12 years, irrespective of SALT score.

Intralesional Therapy with Corticosteroids

Inducing hair regrowth and long-term remission with intralesional corticosteroids (ILC) is more effective than topical steroids. Although subdermal or dermal atrophy episodes may complicate the treatment response, the symptoms usually resolve within 8–16 weeks. Adolescents and adult patients should receive 2.5–10 mg/mL (not more than 10 mg/mL) of diluted triamcinolone acetonide as an initial treatment for patchy AA of the scalp, with a maximum dose of 10–20 mg per session.

Systemic Therapies

Prednisolone can be used as a first-line treatment whenever possible. To achieve long-term remission, the initial prednisolone dose is 0.4–0.6 mg/kg/day, with a gradual taper over 12 weeks.

Steroid-Sparing Therapies

Ciclosporin can be used as an effective monotherapy in adult patients. The recommended dose is 3–5 mg/kg/day for a maximum duration of 6–12 months.

Methotrexate can be used as an effective monotherapy for the treatment of severe AA in both adult and adolescent patients aged 13–18 years. However, combination therapy with steroids can be considered on a case-to-case basis. The target dose in adult patients was 15–20 mg/week, whereas in patients aged < 18 years, the target dose was 0.4 mg/kg/week.

JAKi

Although the ACE guidelines were established in 2020 before the global regulatory approval of baricitinib, it is currently the only oral agent approved and licensed by the FDA for the treatment of AA in adults with > 50% of scalp involvement. Thus, it can be considered a first-line treatment for these patients.

First-Line Treatment in Specific Age Groups

Tables 48 and 49 describe ACE treatment guidelines for AA in children and adolescents.

Treatment Discontinuation

Toxicity and incomplete or no response are common reasons for discontinuing systemic treatment. If vellus regrowth fails to convert to terminal hairs, systemic therapy should be continued for 6 months or longer; however, all treatment should be discontinued once complete regrowth is achieved and maintained for 6 months or when regrowth can be adequately managed with topical therapy.

Dermatologists or patients may be compelled to stop treatment due to the financial burden caused by the high cost of treatment on patients.

Current Treatment Algorithm in the UAE

Dermatologists in the UAE have developed the following treatment recommendations on the basis of actual clinical experience, adapting the ACE and American recommendations for local patient care [90, 91]:

In children younger than 12 years, potent topical steroids are initially applied for 2–3 months if the area of involvement is very small.

In children older than 12 years, adolescents, and adults with < 50% of the area of involvement, ILCs are used with or without 5% minoxidil solution, depending on disease severity.

In children, adolescents, and adults with > 50% of the area of scalp involvement, contact immunotherapy with DPCP is used with or without 5% minoxidil solution, depending on disease severity, before considering systemic therapy.

In adults with > 50% of the area of scalp involvement, the oral JAKi baricitinib has now replaced tofacitinib as the first-line treatment in patients who do not respond to topical steroids/ILCs/minoxidil or those with AT and AU.

Unmet Needs

Africa and the Middle East face substantial challenges in improving the diagnosis and treatment landscape for AA. There are no curative treatments and limited treatment options with variations. Finding a standard treatment for this disease is still challenging, despite advancements in the study of the disease pathway and new treatment possibilities. The following are the main obstacles in the management of AA in the region.

Lack of Regional Epidemiological Data

Clinical information on the prevalence, incidence, and treatment of AA in Africa and the Middle East is limited due to the lack of formal registries. Clinical restrictions at healthcare institutions, such as disparities in assessment and treatment protocols, a lack of consensus on treatment algorithms, and ethical limits on taking samples for skin biopsies are challenges. Most regional studies enroll patients from particular socioeconomic backgrounds, have short follow-up periods, and are monocentric with limited data sources and small sample sizes [10, 57, 92].

Availability of Medications

Due to a lack of approved therapies in the region, there is a high prevalence of patients with mild forms of AA and pediatric populations with severe AA [10, 65].

Financial Burden

The biggest obstacle to patients is getting insurance approval for prescription plan coverage because most insurers view AA as a cosmetic condition rather than a serious health issue. When this aspect is coupled with disparities in subsidiary plans among government pharmacies and dispensaries, patients must incur significant out-of-pocket expenses to receive the required prescriptions, which inevitably leads to relapses due to treatment interruption or discontinuation [65].

Lack of Awareness Among Dermatologists and Patients

There is a low level of understanding of AA among family physicians and patients. In many countries, the physical symptoms of the condition are severely stigmatized, discouraging many patients, especially women, from seeking treatment [10, 57].

Lack of Treatment Access

The region’s AA treatment landscape has numerous gaps, particularly in geographically remote locations, due to a lack of access to appropriate diagnostic tools, compassionate use or early access programs, and appropriate therapeutic resources due to heterogeneity across healthcare facilities [93].

Recommendations to Address Unmet Needs

Educational Initiatives

Initiating awareness campaigns for accurate and updated information on the diagnosis and management of AA is essential. This is critical to address the social stigma associated with AA. Education on the efficacy of novel treatments, discouraging self-medication with over-the-counter drugs, and devoting time and resources to patient counseling at hospital or dermatologist clinics are essential strategies [94]. Raising awareness on the background of autoimmunity as the pathogenesis of AA is essential to moving away from labeling it as a cosmetic condition. Additionally, there is a need for specialized alopecia centers and educators to help establish the aforementioned education and awareness initiatives.

Treatment Accessibility

To develop and enhance availability and access to new medications for AA throughout Africa and the Middle East, cooperation between industry, patients, academia, regulators, and payers is necessary. Considerations for commercial success, such as reimbursement and prospective regulatory approval pathways, must be considered from an industrial perspective. However, the lack of efficient, well-tolerated, and licensed treatments for this indication for all severity levels and a lack of reimbursement precedents in comparable dermatological indications that can support further drug research constitute a clear unmet need. Countries should also target expediting the availability of globally approved drugs, such as novel JAKi to treat patients with severe AA [95].

National Registries

We propose leveraging global databases to develop prototype real-time registries specific to the region to provide insights on AA prevalence, disease burden, and available treatment modalities [92].

Reimbursement Strategies

AA has a complicated insurance reimbursement positioning as it is often considered a cosmetic disease with no life-threatening sequelae. As there is a recent shift in paradigm toward clinically meaningful improvement in patient QoL, regulatory bodies can propose the development of targeted therapies as an indicator to justify costs. Furthermore, significant indirect global benchmarks for reimbursement precedent from other dermatological indications, particularly psoriasis and acne, can potentially be applied to this cause [75].

Regional Consensus

Initiatives should be implemented on a large scale to encourage regional experts to meet for consensus-building group sessions. The existing ACE and local UAE guidelines can be used to formulate and adapt local policies to support clinician decision-making processes. It is essential to factor in the regional patient population’s environmental and lifestyle influences into these guidelines.

Patient Support Programs

We recommend creating patient support programs and organizations throughout healthcare facilities to advocate for funding research and to enable access to treatment for patients of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds [96].

Discussion

This is the first expert review of its kind on the disease burden, treatment landscape, and unmet needs for AA in the Middle East and Africa. Through a comprehensive literature search, we found that Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey have conducted controlled studies evaluating and comparing the efficacy of oral, systemic, topical, and intralesional therapeutic options for AA in both adults and pediatric populations. In contrast, minimal data were reported from Israel, Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, South Africa, UAE, and Kuwait. Since there are currently no standardized treatment protocols that can be shared across regional practitioners, management plans are frequently customized on the basis of hospital facilities, patient preferences, pharmaceutical accessibility, and financial viability. It is unfeasible to undertake an interregional comparison of treatment methods and algorithms due to the lack of established registries and notable differences in the quantity and scope of regional studies conducted across countries.

It was noted that Turkey, Iran, and Egypt investigated therapeutic methods for transepidermal medication delivery, including fractional CO2 laser, microneedling, cryotherapy, latanoprost, and vitamin D3 injections. On the contrary, data from Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the UAE, Lebanon, and Jordan focused more on traditional treatment modalities, such as topical immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester, DPCP, minoxidil, and anthralin, as well as oral or ILCs, or systemic immunosuppressive drugs.

Due to a scarcity of approved therapies for each type of AA, many regional patients resort to alternative therapies to temporarily relieve symptoms. The sum of these treatment costs can cause considerable financial stress to patients. National healthcare authorities and stakeholders cannot estimate the total cost to society, and as a result, decide whether present policies for care and treatment adequately meet unmet needs due to a lack of comprehensive regional data on the prevalence and incidence of AA.

While there is a considerable degree of heterogeneity among healthcare systems of nations in the Middle East and Africa marked by disparities in structure and quality of services, the nature of gaps that hinder the optimal management of AA are often similar [97]. Most countries in this region have a public healthcare system that is underfunded and understaffed [98]. This results in limited access to basic healthcare services for patients suffering from AA. Even in countries such as South Africa, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, where a private healthcare system is available, it is often unaffordable for a significant proportion of the population, thus limiting access to quality healthcare [99,100,101].

The management of AA in the African and Middle Eastern regions is largely also hindered by limited resources, shortages of healthcare professionals, and lack of infrastructure, such as inadequate hospitals, and limited access to essential medical equipment and medications [93]. Topical and oral medications for AA, such as corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, can be expensive and not widely available, especially in countries with a weak economy [102, 103]. Additionally, in some countries there may be restrictions on importing and using certain medications for AA, further complicating the management of the condition.

The economic status of a country plays a critical role in determining the cost of AA medications. In more economically developed countries, such as Saudi Arabia, the cost of treatment may be higher compared with those with weaker economies. In many African countries, where poverty is widespread, the cost of AA medications may still be prohibitively expensive for many individuals, making it difficult for them to access the necessary treatments for their condition. The combination of high cost and limited resources poses a significant challenge to the effective management of AA in many African and Middle Eastern countries.

The development of regional guidelines is critical for establishing relevant management protocols, particularly for patients with severe AA. It is also advisable to provide focused training to family doctors, specialists, and nurses on the early and accurate diagnosis and treatment of this condition. Other initiatives such as the establishment of patient support programs and development of regional consensus statements to standardize care delivery are also warranted. Due to the various unmet needs in the region for effective, well-tolerated, and convenient therapies for AA, both patients and researchers are likely to be interested in trial participation. This could improve the treatment landscape.

Conclusions

We strongly suggest establishing a regional expert forum to outline disease burden, identify knowledge gaps, and develop management protocols relevant to this population. In addition, raising awareness among the general public and establishing patient support programs is key. We hope that through this manuscript, we can provide directives to dermatologists in Africa and the Middle East on ways to enhance the diagnostic and treatment protocols in their countries and improve the QoL for patients with AA.

References

Al-Ajlan A, Alqahtani ME, Alsuwaidan S, Alsalhi A. Prevalence of alopecia areata in Saudi Arabia: cross-sectional descriptive study. Cureus. 2020;12(9): e10347.

Wasserman D, Guzman-Sanchez DA, Scott K, McMichael A. Alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(2):121–31.

Villasante Fricke AC, Miteva M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: a systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397–403.

Alshahrani AA, Al-Tuwaijri R, Abuoliat ZA, Alyabsi M, AlJasser MI, Alkhodair R. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of alopecia areata at a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Dermatol Res Pract. 2020;2020:7194270.

Afford R, Leung AKC, Lam JM. Pediatric alopecia areata. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17(1):45–54.

Chu SY, Chen YJ, Tseng WC, Lin MW, Chen TJ, Hwang CY, et al. Comorbidity profiles among patients with alopecia areata: the importance of onset age, a nationwide population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5):949–56.

Al Hamzawi NK. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of 308-nm monochromatic excimer lamp in the treatment of resistant alopecia areata. Int J Trichol. 2019;11(5):199–206.

Lepe K, Zito PM. Alopecia areata. StatPearls. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

McElwee KJ, Gilhar A, Tobin DJ, Ramot Y, Sundberg JP, Nakamura M, et al. What causes alopecia areata? Exp Dermatol. 2013;22(9):609–26.

Al Hammadi A. A review on disease burden and unmet need of alopecia areata in Africa and Middle East. Poster session presented at: 30th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress; 2021 Oct 13–17; Berlin.

Arousse A, Boussofara L, Mokni S, Gammoudi R, Saidi W, Aounallah A, et al. Alopecia areata in Tunisia: epidemio-clinical aspects and comorbid conditions. A prospective study of 204 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(7):811–5.

Chandrashekar B, Yepuri V, Mysore V. Alopecia areata-successful outcome with microneedling and triamcinolone acetonide. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7(1):63–4.

Khademi F, Tehranchinia Z, Abdollahimajd F, Younespour S, Kazemi-Bajestani SMR, Taheri K. The effect of platelet rich plasma on hair regrowth in patients with alopecia areata totalis: a clinical pilot study. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(4): e12989.

Al-Dhalimi MA, Al Janabi MH, Abd Al Hussein RA. The use of a 1540 nm fractional erbium-glass laser in treatment of alopecia areata. Lasers Surg Med. 2019;51(10):859–65.

Egger A, Tomic-Canic M, Tosti A. Advances in stem cell-based therapy for hair loss. CellR4 Repair Replace Regen Reprogr. 2020;8:2894.

King B, Ohyama M, Kwon O, Zlotogorski A, Ko J, Mesinkovska NA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib for alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(18):1687–99.

Thomas EA, Kadyan RS. Alopecia areata and autoimmunity: a clinical study. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53(2):70–4.

Mane M, Nath AK, Thappa DM. Utility of dermoscopy in alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56(4):407–11.

Castelo-Soccio L. Experience with oral tofacitinib in 8 adolescent patients with alopecia universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(4):754–5.

Pratt CH, King LE Jr, Messenger AG, Christiano AM, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17011.

Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C, Orun E. Prevalence of scalp disorders and hair loss in children. Cutis. 2012;90(5):225–9.

King BA, Mesinkovska NA, Craiglow B, Kindred C, Ko J, McMichael A, et al. Development of the alopecia areata scale for clinical use: results of an academic-industry collaborative effort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(2):359–64.

Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, Hua T, Rastogi S, Ibler E, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(3):675–82.

Oyedepo JT, Katibi OS, Adedoyin OT. Cutaneous disorders of adolescence among Nigerian secondary school students. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:36.

Dlova NC, Mankahla A, Madala N, Grobler A, Tsoka-Gwegweni J, Hift RJ. The spectrum of skin diseases in a black population in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal. South Africa Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(3):279–85.

Kouassi Y. Alopecia areata in Black African patients: lopecia areata in Black African patients: epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic aspects. Our Dermatol. 2021;12(1):24–6.

Al HA. The pattern of skin diseases in Karbala city: a retrospective study. Al-Qadisha Med J. 2011;7:117–28.

Senel E, Dogruer Senel S, Salmanoglu M. Prevalence of skin diseases in civilian and military population in a Turkish military hospital in the central Black Sea region. J R Army Med Corps. 2015;161(2):112–5.

Al-Refu K. Hair loss in children: common and uncommon causes; clinical and epidemiological study in Jordan. Int J Trichology. 2013;5(4):185–9.

Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Prescott L, Welch V, Delamere FM, Nasser M, et al. Global burden of skin disease as reflected in Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(9):945–51.

Wang H, Pan L, Wu Y. Epidemiological trends in alopecia areata at the global, regional, and national levels. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 874677.

Nasimi M, Ghandi N, Torabzade L, Shakoei S. Alopecia Areata-Quality of Life Index Questionnaire (reliability and validity of the Persian version) in comparison to dermatology life quality index. Int J Trichology. 2020;12(5):227–33.

Nasimi M, Abedini R, Ghandi N, Manuchehr F, Kazemzadeh Houjaghan A, Shakoei S. Illness perception in patients with alopecia areata under topical immunotherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2): e14748.

Abedini R, Hallaji Z, Lajevardi V, Nasimi M, Karimi Khaledi M, Tohidinik HR. Quality of life in mild and severe alopecia areata patients. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4(2):91–4.

Savaş Erdoğan S, Falay Gür T, Doğan B. Anxiety and depression in pediatric patients with vitiligo and alopecia areata and their parents: a cross-sectional controlled study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(7):2232–9.

Bilgiç Ö, Bilgiç A, Bahalı K, Bahali AG, Gürkan A, Yılmaz S. Psychiatric symptomatology and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(11):1463–8.

Al-Mutairi N, Eldin ON. Clinical profile and impact on quality of life: seven years experience with patients of alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77(4):489–93.

Essa N, Awad S, Nashaat M. Validation of an Egyptian Arabic version of skindex-16 and quality of life measurement in Egyptian patients with skin disease. Int J Behav Med. 2018;25(2):243–51.

Mahgoub DA, Dhannoon TI, El-Mesidy MS. Trichloroacetic acid 35% as a therapeutic line for localized patchy alopecia areata in comparison with intralesional steroids: clinical and trichoscopic evaluation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(6):1743–9.

Masmoudi J, Sellami R, Ouali U, Mnif L, Feki I, Amouri M, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a sample of Tunisian patients. Dermatol Res Pract. 2013;2013: 983804.

Matzer F, Egger JW, Kopera D. Psychosocial stress and coping in alopecia areata: a questionnaire survey and qualitative study among 45 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91(3):318–27.

Sellami R, Masmoudi J, Ouali U, Mnif L, Amouri M, Turki H, et al. The relationship between alopecia areata and alexithymia, anxiety and depression: a case-control study. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(4):421.

Chu SY, Chen YJ, Tseng WC, Lin MW, Chen TJ, Hwang CY, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with alopecia areata in Taiwan: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(3):525–31.

Bakry OA, Basha MA, El Shafiee MK, Shehata WA. Thyroid disorders associated with alopecia areata in Egyptian patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(1):49–55.

Bin Saif GA. Severe subtype of alopecia areata is highly associated with thyroid autoimmunity. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(6):656–61.

Alamoudi SM, Marghalani SM, Alajmi RS, Aljefri YE, Alafif AF. Association between vitamin D and zinc levels with alopecia areata phenotypes at a tertiary care center. Cureus. 2021;13(4): e14738.

Isa HM, Farid E, Makhlooq JJ, Mohamed AM, Al-Arayedh JG, Alahmed FA, et al. Celiac disease in children: increasing prevalence and changing clinical presentations. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2021;64(6):301–9.

El-Sayed-Mahmoud-Marie R, El-Sayed GAK, Attia FM, Gomaa AHA. Evaluation of serum cardiac troponin I and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels in patients with alopecia areata. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46(1):153–6.

Li SJ, Mostaghimi A, Tkachenko E, Huang KP. Association of out-of-pocket health care costs and financial burden for patients with alopecia areata. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(4):493–4.

Moosavi ZB, Aliabdi M, Golfakhrabadi F, Namjoyan F. The comparison of therapeutic effect of clobetasol propionate lotion and squill extract in alopecia areata: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Arch Dermatol Res. 2020;312(3):173–8.

Ghandi N, Seifi G, Nasimi M, Abedini R, Mirabedian S, Etesami I, et al. Is the severity of initial sensitization to diphenylcyclopropenone in alopecia areata patients predictive of the final clinical response? Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(6): e15118.

Nasiri S, Haghpanah V, Taheri E, Heshmat R, Larijani B, Saeedi M. Hair regrowth with topical triiodothyronine ointment in patients with alopecia areata: a double-blind, randomized pilot clinical trial of efficacy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(5):654–6.

Ghandi N, Daneshmand R, Hatami P, Abedini R, Nasimi M, Aryanian Z, et al. A randomized trial of diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) combined with anthralin versus DPCP alone for treating moderate to severe alopecia areata. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;99: 107971.

Abedini R, Alipour E, Ghandi N, Nasimi M. Utility of dermoscopic evaluation in predicting clinical response to diphencyprone in a cohort of patients with alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2020;12(3):107–13.

Nasimi M, Abedini R, Ghandi N, Seirafi H, Mehdizade MS, Tootoonchi N. Topical immunotherapy with diphenylcyclopropenone in patients with alopecia areata: a large retrospective study of 757 patients. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6): e13808.

Abedini H, Farshi S, Mirabzadeh A, Keshavarz S. Antidepressant effects of citalopram on treatment of alopecia areata in patients with major depressive disorder. J Dermatol Treat. 2014;25(2):153–5.

Farshi S, Mansouri P, Safar F, Khiabanloo SR. Could azathioprine be considered as a therapeutic alternative in the treatment of alopecia areata? A pilot study Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(10):1188–93.

Asilian A, Fatemi F, Ganjei Z, Siadat AH, Mohaghegh F, Siavash M. Oral pulse betamethasone, methotrexate, and combination therapy to treat severe alopecia areata: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Iran J Pharm Res. 2021;20(1):267–73.

Kutlubay Z, Sevim A, Aydin O, Vehid S, Serdaroglu S. Assessment of treatment efficacy of diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) for alopecia areata. Turk J Med Sci. 2020;50(8):1817–24.

Unal M. Use of adapalene in alopecia areata: Efficacy and safety of mometasone furoate 0.1% cream versus combination of mometasone furoate 0.1% cream and adapalene 0.1% gel in alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31(1):12574.

Ozdemir M, Balevi A. Bilateral half-head comparison of 1% anthralin ointment in children with alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(2):128–32.

Durdu M, Özcan D, Baba M, Seçkin D. Efficacy and safety of diphenylcyclopropenone alone or in combination with anthralin in the treatment of chronic extensive alopecia areata: a retrospective case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(4):640–50.

Ucak H, Kandi B, Cicek D, Halisdemir N, Dertlıoğlu SB. The comparison of treatment with clobetasol propionate 0.05% and topical pimecrolimus 1% treatment in the treatment of alopecia areata. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23(6):410–20.

Askin O, Yucesoy SN, Coskun E, Engin B, Serdaroglu S. Evaluation of the level of serum interleukins (IL-2, IL-4, IL-15 andIL-17) and its relationship with disease severity in patients with alopecia areata. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96(5):551–7.

Dincer Rota D, Emeksiz MAC, Erdogan FG, Yildirim D. Experience with oral tofacitinib in severe alopecia areata with different clinical responses. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(9):3026–33.

Serdaroglu S, Engin B, Celik U, Erkan E, Askin O, Oba C, et al. Clinical experiences on alopecia areata treatment with tofacitinib: a study of 63 patients. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(3): e12844.

Aşkın Ö, Özkoca D, Uzunçakmak TK, Serdaroğlu S. Evaluation of the alopecia areata patients on tofacitinib treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2): e14746.

Acikgoz G, Caliskan E, Tunca M, Yeniay Y, Akar A. The effect of oral cyclosporine in the treatment of severe alopecia areata. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2014;33(3):247–52.

Ustuner P, Balevi A, Ozdemir M. Best dilution of the best corticosteroid for intralesional injection in the treatment of localized alopecia areata in adults. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28(8):753–61.

Almutairi N. Janus kinase inhibitors for the treatment of severe alopecia areata: an open-label comparative study. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2018;235(2):130–6.

Muhaidat JM, Al-Qarqaz F, Khader Y, Alshiyab DM, Alkofahi H, Almalekh M. A retrospective comparative study of two concentrations of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide in the treatment of patchy alopecia areata on the scalp. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:795–803.

Anderi R, Makdissy N, Azar A, Rizk F, Hamade A. Cellular therapy with human autologous adipose-derived adult cells of stromal vascular fraction for alopecia areata. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):141.

El Khoury J, Abd-el-Baki J, Succariah F, Abbas O, Kibbi AG, Kurban M. Topical immunomodulation with diphenylcyclopropenone for alopecia areata: the Lebanese experience. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(12):1551–6.

AlMarzoug A, AlOrainy M, AlTawil L, AlHayaza G, AlAnazi R, AlIssa A, et al. Alopecia areata and tofacitinib: a prospective multicenter study from a Saudi population. Int J Dermatol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15917.

Bin Saif GA, Al-Khawajah MM, Al-Otaibi HM, Al-Roujayee AS, Alzolibani AA, Kalantan HA, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral mega pulse methylprednisolone for severe therapy resistant alopecia areata. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(3):284–91.

Ngwanya MR, Gray NA, Gumedze F, Ndyenga A, Khumalo NP. Higher concentrations of dithranol appear to induce hair growth even in severe alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30(4):12500.

Friedland R, Tal R, Lapidoth M, Zvulunov A, Ben AD. Pulse corticosteroid therapy for alopecia areata in children: a retrospective study. Dermatology. 2013;227(1):37–44.

Lyakhovitsky A, Aronovich A, Gilboa S, Baum S, Barzilai A. Alopecia areata: a long-term follow-up study of 104 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(8):1602–9.

Hunter N, Shaker O, Marei N. Diphencyprone and topical tacrolimus as two topical immunotherapeutic modalities. Are they effective in the treatment of alopecia areata among Egyptian patients? A study using CD4, CD8 and MHC II as markers. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22(1):2–10.

Kamel MM, Salem SA, Attia HH. Successful treatment of resistant alopecia areata with a phototoxic dose of ultraviolet A after topical 8-methoxypsoralen application. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27(1):45–50.

Zaher H, Gawdat HI, Hegazy RA, Hassan M. Bimatoprost versus mometasone furoate in the treatment of scalp alopecia areata: a pilot study. Dermatology. 2015;230(4):308–13.

El-Ashmawy AA, El-Maadawy IH, El-Maghraby GM. Efficacy of topical latanoprost versus minoxidil and betamethasone valerate on the treatment of alopecia areata. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29(1):55–64.

Hamdino M, El-Barbary RA, Darwish HM. Intralesional methotrexate versus triamcinolone acetonide for localized alopecia areata treatment: a randomized clinical trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(2):707–15.

Albalat W, Ebrahim HM. Evaluation of platelet-rich plasma vs intralesional steroid in treatment of alopecia areata. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.12858.

Abdallah MAE, Shareef R, Soltan MY. Efficacy of intradermal minoxidil 5% injections for treatment of patchy non-severe alopecia areata. J Dermatol Treat. 2022;33(2):1126–9.

Metwally D, Abdel-Fattah R, Hilal RF. Comparative study for treatment of alopecia areata using carboxy therapy, intralesional corticosteroids, and a combination of both. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022;314(2):167–82.

Messenger AG, McKillop J, Farrant P, McDonagh AJ, Sladden M. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of alopecia areata 2012. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(5):916–26.

Rossi A, Muscianese M, Piraccini BM, Starace M, Carlesimo M, Mandel VD, et al. Italian Guidelines in diagnosis and treatment of alopecia areata. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2019;154(6):609–23.

Wolff H, Fischer TW, Blume-Peytavi U. The diagnosis and treatment of hair and scalp diseases. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(21):377–86.

Phillips TG, Slomiany WP, Allison R. Hair loss: common causes and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(6):371–8.

Meah N, Wall D, York K, Bhoyrul B, Bokhari L, Sigall DA, et al. The Alopecia Areata Consensus of Experts (ACE) study: results of an international expert opinion on treatments for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(1):123–30.

Wall D, Meah N, York K, Bhoyrul B, Bokhari L, Abraham LS, et al. A global eDelphi exercise to identify core domains and domain items for the development of a Global Registry of Alopecia Areata Disease Severity and Treatment Safety (GRASS). JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(4):1–11.

Kankeu HT, Saksena P, Xu K, Evans DB. The financial burden from non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a literature review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:31.

Kim BK, Lee S, Jun M, Chung HC, Oh SS, Lee WS. Perception of hair loss and education increases the treatment willingness in patients with androgenetic alopecica: a population-based study. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30(4):402–8.

Wagner AT. Industry perspective on alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2015;17(2):67–9.

Ganguli A, Clewell J, Shillington AC. The impact of patient support programs on adherence, clinical, humanistic, and economic patient outcomes: a targeted systematic review. Patient Prefer Adher. 2016;10:711–25.

Mate K. Review of health systems of the Middle East and North Africa region. International Encyclopedia of Public Health; 2017. p. 347–56.

Katoue MG, Cerda AA, Garcia LY, Jakovljevic M. Healthcare system development in the Middle East and North Africa region: challenges, endeavors and prospective opportunities. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1045739.

Kronfol NM. Access and barriers to health care delivery in Arab countries: a review. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(12):1239–46.

Gordon T, Booysen F, Mbonigaba J. Socio-economic inequalities in the multiple dimensions of access to healthcare: the case of South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):289.

Alkhamis AA. Critical analysis and review of the literature on healthcare privatization and its association with access to medical care in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10(3):258–68.

Adebisi YA, Nwogu IB, Alaran AJ, Badmos AO, Bamgboye AO, Rufai BO, Okonji OC, Malik MO, Teibo JO, Abdalla SF, Lucero-Prisno DE III, Mohamed S, Wuraola A-S. Revisiting the issue of access to medicines in Africa: challenges and recommendations. Public Health Chall. 2022;1(2):e9.

Ozoh OB, Eze JN, Garba BI, Ojo OO, Okorie EM, Yiltok E, et al. Nationwide survey of the availability and affordability of asthma and COPD medicines in Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26(1):54–65.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by Pfizer Inc. Ltd., which includes funding of the rapid service fee, open access fee, and medical writing support.

Medical Writing

Medical writing support was provided by Shilpa Bhat, formerly of Connect Communications, Dubai and Luqman Khan of Connect Communications, Dubai and was funded by Pfizer Inc. Ltd.

Author Contributions

All authors were equally involved in the curation and development of this review (A.H, N.P, K.J, O.S, M.A, H.M, A.A). All authors contributed equally to the conceptualization, literature search, data analysis, and development and review of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Haytham Ahmed Mohamed is an employee of Pfizer Inc. Ltd. Anwar Al Hammadi, Nisha V Parmar, Khadija Aljefri, Osama Al Sharif, Marwa Abdallah, and Alfred Ammoury have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Hammadi, A., Parmar, N.V., Aljefri, K. et al. Review on Alopecia Areata in the Middle East and Africa: Landscape and Unmet Needs. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13, 1435–1464 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00946-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00946-8