Abstract

Introduction

Tildrakizumab (TIL), a monoclonal antibody that selectively targets interleukin-23p19, has been approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. According to the European Medicines Agency Summary of Product Characteristics, the recommended dose is 100 mg, but a 200 mg dose can be used in patients with certain characteristics, such as a high disease burden or body weight (BW) ≥ 90 kg. Fixed one-dose biological therapies tend to become less effective in patients with high BW. This post-hoc study describes the long-term efficacy of TIL across different BWs in pivotal clinical trials.

Methods

A 5-year pooled analysis of two double-blind, randomised, controlled phase III trials—reSURFACE 1 and 2—was performed. Efficacy measures were the proportions of the patients with an absolute Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) of < 3 and < 1 and a Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) of 0/1. The study population included patients randomised to TIL 100 mg or TIL 200 mg who received ≥ 1 TIL dose up to week 12 (part 1 of the trial) or up to week 28 (part 2) and patients who were responders (≥ 75% improvement in PASI) to TIL 100 or TIL 200 mg at week 28 and who were maintained on the same dose up to week 244. Efficacy was evaluated by analysing BW subgroups at weeks 28, 52 and 244. Missing data were analysed using multiple imputation. Safety was assessed in the all-patients-as-treated population.

Results

The proportions of TIL-treated patients with PASI < 3 and < 1 (up to week 244) and DLQI 0/1 (up to week 52) were similar for patients with BW < 90 or ≥ 90 kg, regardless of dose. Patients ≥ 120 kg had greater efficacy outcomes at the 200 mg dose. Safety outcomes were similar regardless of treatment dose and weight (< 120/≥ 120 kg).

Conclusion

In patients with BW ≥ 120 kg, TIL 200 mg is more efficacious than TIL 100 mg, with similar favourable safety profiles obtained regardless of dose and BW group.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01722331 (reSURFACE 1) and NCT01729754 (reSURFACE 2).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this analysis? |

Biologic treatments for psoriasis often show differences in efficacy depending on the patient's weight. |

For some biologics, a diminished clinical response has been described in patients with higher weight. |

There is limited evidence on the impact of body weight on the effects of tildrakizumab (TIL) at different doses. |

The effects of weight on drug efficacy and safety for two different doses of TIL (100 mg and 200 mg) have not been reported in sufficient detail. |

What was learned from this analysis? |

Both doses of TIL were similarly efficacious in patients ≥ 90 kg and < 90 kg. |

Patients with body weight ≥ 120 kg achieve better responses with TIL 200 mg compared to TIL 100 mg. |

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease that affects patients globally [1]. The disease is associated with being overweight, obesity, and increased abdominal and visceral fat [2]. Psoriasis in obese patients responds less effectively to treatments, including various biological therapies [3,4,5]. The detrimental effect of body weight (BW) or body mass on therapeutic response could be explained in part by the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of biologics. The pharmacokinetics of biologics are influenced by BW [6], and increasing BW decreases serum concentrations and increases total serum clearance and volume of distribution [7, 8]. In addition, the negative effects of obesity on therapeutic response may also include the up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by adipose tissue [9, 10].

Tildrakizumab (TIL, SCH-900222, MK-3222) is a humanised anti-interleukin (IL)-23p19 monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis in adults [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Tildrakizumab inhibits the IL-23/IL-17 axis, the signalling pathway primarily involved in the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis [17]. Tildrakizumab prevents the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and has a limited impact on the rest of the immune system [18].

Pooled data from the reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2 phase III trials showed equal sustained efficacy, maintenance of response, and safety over 5 years with TIL 100 and 200 mg in moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis patients [19]. Moreover, TIL 100 mg has been shown to be highly effective and well tolerated in real-world practice [20,21,22,23]. As per the label, the recommended dose of TIL is 100 mg administered at 0 and 4 weeks and then every 12 weeks thereafter. The European Medicines Agency TIL Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) provides prescribers with the opportunity to use the 200 mg dose in patients with certain characteristics (e.g. a high disease burden, BW ≥ 90 kg). However, limited evidence is available on the effect of patient BW on the response to TIL 100 mg and 200 mg.

The objective of the present study was to examine the impact of BW on the efficacy response to TIL 100 mg and 200 mg over 5 years in the pivotal reSURFACE trials [24], including long-term extensions [19, 25]. Efficacy analyses included pooled patients randomised to TIL 100 mg and 200 mg in the pivotal studies [24], with efficacy defined as achieving a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) of < 3, a PASI of < 1 and/or a Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) of 0 or 1.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

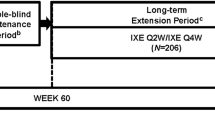

The reSURFACE 1 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01722331) and reSURFACE 2 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01729754) phase III trials evaluated the efficacy and safety of TIL in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis for up to 5 years [19, 25]. reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2 were three-part, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials; reSURFACE 2 included an active comparator arm (etanercept) [24].

The detailed baseline study inclusion and exclusion criteria, patient characteristics, treatment, and methodology have been previously published [24, 25]. Briefly, a total of 1,862 patients ≥ 18 years old with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis diagnosed ≥ 6 months prior to enrolment with a body surface area of ≥ 10%, a Physician's Global Assessment of ≥ 3 and a PASI of ≥ 12 were included in these pivotal clinical trials (772 in reSURFACE 1 and 1090 in reSURFACE 2) [24]. Patients were randomised to TIL 100 mg, TIL 200 mg or placebo in reSURFACE 1 (2:2:1), or to TIL 100 mg, TIL 200 mg, placebo or etanercept 50 mg in reSURFACE 2 (2:2:1:2). reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2 included three parts: part 1, weeks 0–12; part 2, weeks 12–28; and part 3, weeks 28–64 (reSURFACE 1)/52 (reSURFACE 2). Tildrakizumab 100 mg and 200 mg were administered subcutaneously at weeks 0 and 4 and every 12 weeks thereafter. At week 28, patients with a ≥ 75% improvement in baseline PASI (PASI 75 responders) in reSURFACE 1 were re-randomised to continue the same TIL dose or to receive placebo; in reSURFACE 2, PASI 75 responders to TIL 200 mg were re-randomised to TIL 100 or 200 mg, while PASI 75 responders to TIL 100 mg maintained the same dose. At week 64 (reSURFACE 1) or week 52 (reSURFACE 2), patients with an improvement of ≥ 50% from baseline PASI entered an optional extension period of up to week 256 (reSURFACE 1) or week 244 (reSURFACE 2) [19, 25]. The investigators, participants, study staff and analysis team did not know the treatment assignment until all patients had completed the third part (Fig. 1).

Study design. White letters represent differences between the reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2 trials. The sample assessed for efficacy in this study is shown in red. D/C discontinued, NR non-responder (< 50% improvement in PASI), PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, PR partial responder (50–75% improvement in PASI), R responder (≥ 75% improvement in PASI), TIL tildrakizumab

Both the reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2 trials were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. The study protocols received local institutional review board or ethics committee approvals. All subjects provided written informed consent to participate in the trials. The study sites of these trials have been previously described [24].

Assessments

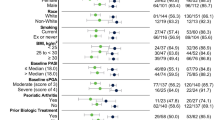

Efficacy outcomes were defined as the proportions of patients who achieved absolute PASI < 3 and PASI < 1 throughout 5 years of treatment—that is, at week 28, week 52 (1 year) and week 244 (5 years)—and DLQI 0/1 responses at week 28 and week 52 (1 year). All analyses were stratified into BW < 60 kg, 60 ≤ BW < 80 kg, 80 ≤ BW < 100 kg, 100 ≤ BW < 120 kg, and BW ≥ 120 kg groups (henceforth “20 kg BW groups”), and comparisons of < 90 kg versus ≥ 90 kg BW patients and < 120 kg versus ≥ 120 kg BW patients were performed.

Safety assessments focused on adverse events (AEs). Pre-specified treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) comprised severe infections, malignancies, non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), melanoma, confirmed extended major adverse cardiovascular events, injection site reactions and drug-related hypersensitivity reactions [24, 25]. Adverse events were assessed at all study visits during the base period pool (three parts) plus the extension period up to weeks 256/244 over 5 years for TIL 100 mg versus 200 mg, separately, and were stratified into BW < 120 kg versus ≥ 120 kg. Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred terms for each AE were assigned to the treatment dose that the patient was actively receiving when the AE occurred.

Statistical Analyses

No formal hypothesis testing was performed for these post hoc analyses. Based on the authors’ expert opinion, a difference of ~ 15% in response rates was considered clinically meaningful. All subjects randomised to TIL 100 mg and TIL 200 mg who received at least one dose of the part 1 or part 2 study medication were included in the week 28 analyses (TIL 100 mg: n = 593; TIL 200 mg: n = 597), while all patients who were responders at week 28 and who continued treatment with the same TIL dose were included in the long-term analyses (weeks 52 and 244) (TIL 100 mg: n = 329; TIL 200 mg: n = 227).

Efficacy analyses used a multiple imputation approach (10 imputations) for missing data, as previously described [25]. Assessments at weeks 28, 52 and 244 are reported. Observed cases were used as sensitivity analyses at week 28: Pearson’s correlation (r) was calculated for the relationship between BW and efficacy endpoints.

Safety analyses were performed in the all-patients-as-treated population, including all patients who received at least one dose of the study drug according to the treatment received (n = 1800). Safety data from week 0 through 5 years were pooled between reSURFACE 1 (up to week 256) and reSURFACE 2 (up to week 244) and were presented for patients who received TIL 100 mg or TIL 200 mg during any part of the study, with a BW of 120 kg used as the comparison threshold. Safety data are reported as the number of events per 100 patient-years of exposure; exposure-adjusted incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed as previously described [24, 25].

Results

The demographic and baseline characteristics of the patients are reported elsewhere [24, 25] and were similar across treatment groups.

Efficacy Outcomes

A total of 593 and 597 patients randomised to TIL 100 mg and TIL 200 mg, respectively, were included in week 28 analyses, while a total of 329 responders to TIL 100 mg and 227 responders to TIL 200 mg at week 28 were included in week 52 and week 244 analyses.

The proportions (95% CIs) of patients treated with TIL 100 mg and TIL 200 mg and stratified by BW < 90 kg, ≥ 90 kg, < 120 kg and ≥ 120 kg who achieved absolute PASI scores < 3 at each timepoint (weeks 28, 52 and 244) are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2. The most notable differences between the two doses are observed for the ≥ 120 kg group, which shows that more patients achieved PASI < 3 when they were treated with TIL 200 mg. Similar results were found for PASI < 3 and PASI < 1 scores stratified by 20 kg BW group (see Table 2 and Figs. 3 and 4), especially at weeks 52 and 244 (although the proportion of responders was higher for PASI 3 at those weeks).

The proportions (95% CIs) of the patients who were treated with TIL 100 mg and TIL 200 mg and had BW < 90 kg, ≥ 90 kg, < 120 kg and ≥ 120 kg who achieved DLQI 0/1 scores at weeks 28 and 52 are shown in Table 1 and in Fig. 5. The most notable differences between the TIL 100 mg and 200 mg doses are again seen for the heaviest patients, with the ≥ 120 kg group treated with the TIL 200 mg dose showing the highest proportion of patients who achieved DLQI 0/1.

Sensitivity analyses (Figs. 6 and 7) showed no significant relationship between BW in kg and changes in efficacy endpoints from baseline. The correlation between the absolute change in PASI score from baseline at week 28 and BW was r = 0.046 (p = 0.276) in the TIL 100 mg cohort and r = 0.012 (p = 0.773) in the TIL 200 mg cohort. The correlation between the absolute change in DLQI score from baseline at week 28 and BW was r = 0.043 (p = 0.302) in the TIL 100 mg cohort and r = 0.029 (p = 0.484) in the TIL 200 mg cohort.

Safety Outcomes

Exposure-adjusted incidence rates of TEAEs are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the treatment and BW groups in rate of TEAEs. The cumulative incidence for TIL 100 mg/TIL 200 mg treatment in patients < 120 kg versus patients ≥ 120 kg was 18/16 versus 3/1 per 100 patient-years of exposure for malignancy excluding NMSC, 13 in both cases versus 1/3 per 100 patient-years of exposure for NMSC, 3 in both cases versus 0 per 100 patient-years of exposure for melanoma, and 9/5 versus 0 per 100 patient-years of exposure for drug-related serious AEs leading to discontinuation (Table 3).

Discussion

The current work presents post-hoc efficacy and safety analyses by BW of randomised subjects who received at least one dose of TIL (week 28 results) and of responders at week 28 who entered TIL extension treatments (100 mg and 200 mg) and received continuous TIL treatment through week 244 (week 52 and week 244 results). For the overall dataset at week 28, no correlation was found between PASI or DLQI change from baseline and BW, indicating a limited impact of BW on the TIL response in the general psoriasis study population. Moreover, PASI < 3, PASI < 1 and DLQI 0/1 response rates were similar for TIL 100 mg and 200 mg in patients with BW > 90 kg, with no clinically meaningful difference consistently observed at weeks 28, 52 and 244. On the other hand, patients with ≥ 120 kg demonstrated a consistent trend toward greater clinical benefit from TIL 200 mg compared to TIL 100 mg across endpoints and time points. Likewise, when considering the PASI < 3 and PASI < 1 response rates for the two doses in subgroups of 20 kg BW intervals, a consistent numerical difference in favour of TIL 200 mg across time points only appeared for the heaviest patients (> 120 kg). The SmPC of TIL [18], in which early PK and PD models from 2017 are outlined, indicates that exposure to TIL decreases with increasing BW. In this regard, the mean exposure in adult patients weighing > 90 kg after a dose of TIL 100 mg or 200 mg was predicted to be approximately 30% lower than that in an adult patient weighing ≤ 90 kg. Consequently, while TIL 100 mg is the recommended dose, the European TIL label provides prescribers with the opportunity to use the 200 mg dose in patients with “certain characteristics”, and mentions BW ≥ 90 kg as one possible example [18]. Our pooled analyses of the complete phase III trial dataset including extensions suggest that 120 kg may be a more appropriate weight cut-off point to guide clinical decision-making.

The safety analyses showed equal rates of AEs for different doses and for BW < 120 kg or ≥ 120 kg, thus suggesting that the potential additional benefit of 200 mg in patients > 120 kg does not come with a safety trade-off.

An increasing number of reports are establishing a negative impact of obesity on response to biological therapies [9, 26,27,28]. Prevalences of overweight and obese patients in clinical registries range between 40% [5, 29] and 57% [30], and 29% [29] and 30% [5], respectively, with overweight/obese patients showing lower responses to biologics and a higher risk of treatment discontinuation [31,32,33,34].

Diminished responses in obese patients with psoriasis have been reported for every class of biological agents [35]. For tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, several studies demonstrate that obesity and BW appear to be predictors of inferior clinical response to anti-TNF agents (i.e. etanercept, adalimumab) in different immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis [36,37,38,39,40]. For IL-12/23 antagonists (i.e. ustekinumab), reduced efficacy (PASI) outcomes have been found with increasing body mass [41,42,43,44]. The clinical efficacies of IL-17 inhibitors (i.e. secukinumab, bimekizumab, ixekizumab) in overweight [45] and/or obese [46] psoriatic patients appear to be lower than those in non-obese patients, with dose optimisation appearing to be highly beneficial clinically for patients with higher body weight [47, 48]. Recent real-world evidence suggests that an obese or overweight status might lead to decreased efficacy, even in IL-23p19 inhibitors (i.e. guselkumab, risankizumab) [49,50,51,52]. In clinical trials, however, this was not the case [53, 54]. Considering these previously reported findings, along with the data presented here for TIL, a lower clinical response to all approved biological therapies is more likely in psoriasis patients with high BW, who may benefit from intensified dosing, which may be more difficult to accommodate with fixed-dose biological therapies.

The main limitation of this analysis is the relatively small number of patients with a BW of over 120 kg, corresponding to ~ 8–9% of the study population, but this distribution is largely representative of the general psoriasis population [55, 56].

Conclusion

Tildrakizumab 100 mg has been demonstrated to provide long-term control with a favourable safety profile both in clinical trials and in real-world practice [19,20,21,22, 57]. The data presented here suggest that TIL 200 mg may be more efficacious than the standard 100 mg dose in patients weighing ≥ 120 kg.

References

Campanati A, Marani A, Martina E, Diotallevi F, Radi G, Offidani A. Psoriasis as an immune-mediated and inflammatory systemic disease: from pathophysiology to novel therapeutic approaches. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1511.

Balci A, Balci DD, Yonden Z, Korkmaz I, Yenin JZ, Celik E, et al. Increased amount of visceral fat in patients with psoriasis contributes to metabolic syndrome. Dermatology. 2010;220:32–7.

Puig L. Obesity and psoriasis: body weight and body mass index influence the response to biological treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1007–11.

Clark L, Lebwohl M. The effect of weight on the efficacy of biologic therapy in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:443–6.

Loft N, Egeberg A, Rasmussen MK, Bryld LE, Nissen CV, Dam TN, et al. Prevalence and characterization of treatment-refractory psoriasis and super-responders to biologic treatment: a nationwide study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18126. Cited 8 Apr 2022.

Zhao L, Ren T, Wang DD. Clinical pharmacology considerations in biologics development. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33:1339–47.

Zhu Y, Hu C, Lu M, Liao S, Marini JC, Yohrling J, et al. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of ustekinumab, a human monoclonal antibody targeting IL-12/23p40, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:162–75.

Weisman M, Moreland L, Furst D, Weinblatt M, Keystone E, Paulus H, et al. Efficacy, pharmacokinetic, and safety assessment of adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha monoclonal antibody, in adults with rheumatoid arthritis receiving concomitant methotrexate: a pilot study. Clin Ther. 2003;25:1700–21.

Wong Y, Nakamizo S, Tan KJ, Kabashima K. An update on the role of adipose tissues in psoriasis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1507.

Rodríguez-Cerdeira C, Cordeiro-Rodríguez M, Carnero-Gregorio M, López-Barcenas A, Martínez-Herrera E, Fabbrocini G, et al. Biomarkers of inflammation in obesity-psoriatic patients. Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:7353420.

Tildrakizumab MA. First global approval. Drugs. 2018;78:845–9.

Papp K, Thaçi D, Reich K, Riedl E, Langley RG, Krueger JG, et al. Tildrakizumab (MK-3222), an anti-interleukin-23p19 monoclonal antibody, improves psoriasis in a phase IIb randomized placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:930–9.

Beck K, Sanchez I, Yang E, Liao W. Profile of tildrakizumab-asmn in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: evidence to date. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2018;8:49–58.

Yiu ZZN, Warren RB. The potential utility of tildrakizumab: an interleukin-23 inhibitor for the treatment of psoriasis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26:243–9.

Gupta AK, Versteeg SG, Abramovits W, Vincent KD. Ilumya® (tildrakizumab): a newly approved interluekin-23 antagonist for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. Skinmed. 2018;16:321–4.

Paton DM. Tildrakizumab: monoclonal antibody against IL-23p19 for moderate to severe psoriasis. Drugs Today (Barc). 2018;54:433–44.

Frampton JE. Tildrakizumab: a review in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:295–306.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Ilumetri. 2018. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/ilumetri. Cited 7 Feb 2022.

Thaci D, Piaserico S, Warren RB, Gupta AK, Cantrell W, Draelos Z, et al. Five-year efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who respond at week 28: pooled analyses of two randomized phase III clinical trials (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2). Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:323–34.

Drerup KA, Seemann C, Gerdes S, Mrowietz U. Effective and safe treatment of psoriatic disease with the anti-IL-23p19 biologic tildrakizumab: results of a real-world prospective cohort study in nonselected patients. Dermatology. 2021;2:1–5.

Galán-Gutierrez M, Freire L, Ruiz-Villaverde R. Tildrakizumab: short-term efficacy and safety in real clinical practice. Int J Dermatol. 2021;2:5.

Burlando M, Castelli R, Cozzani E, Parodi A. Treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis with tildrakizumab in the real-life setting. Drugs Context. 2021;10:2–6.

Wei NW, Chi S, Lebwohl MG. Retrospective analysis in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis treated with tildrakizumab: real-life clinical data. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2022;7:55–9.

Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Tyring SK, Sinclair R, Thaçi D, et al. Tildrakizumab versus placebo or etanercept for chronic plaque psoriasis (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2): results from two randomised controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2017;390:276–88.

Reich K, Warren RB, Iversen L, Puig L, Pau-Charles I, Igarashi A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: pooled analyses of two randomized phase III clinical trials (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2) through 148 weeks. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:605–17.

Johnston A, Arnadottir S, Gudjonsson JE, Aphale A, Sigmarsdottir AA, Gunnarsson SI, et al. Obesity in psoriasis: leptin and resistin as mediators of cutaneous inflammation. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:342–50.

Xu C, Ji J, Su T, Wang H-W, Su Z-L. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116–21.

Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633–9.

Carrascosa JM, Vilavella M, Garcia-Doval I, Carretero G, Vanaclocha F, Daudén E, et al. Body mass index in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in Spain and its impact as an independent risk factor for therapy withdrawal: results of the Biobadaderm Registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:907–14.

Shalom G, Naldi L, Lebwohl M, Nikkels A, Jong E, Fakharzadeh S, et al. Biological treatment for psoriasis and the risk of herpes zoster: results from the psoriasis longitudinal assessment and registry (PSOLAR). J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:534–9.

Bassi M, Singh S. Impact of obesity on response to biologic therapies in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. BioDrugs. 2022;36:197–203.

Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Cook RJ, Gladman DD. Obesity is associated with a lower probability of achieving sustained minimal disease activity state among patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:813–7.

Kurnool S, Nguyen NH, Proudfoot J, Dulai PS, Boland BS, Vande Casteele N, et al. High body mass index is associated with increased risk of treatment failure and surgery in biologic-treated patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:1472–9.

Mourad A, Straube S, Armijo-Olivo S, Gniadecki R. Factors predicting persistence of biologic drugs in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:450–8.

Pirro F, Caldarola G, Chiricozzi A, Burlando M, Mariani M, Parodi A, et al. Impact of body mass index on the efficacy of biological therapies in patients with psoriasis: a real-world study. Clin Drug Investig. 2021;41:917–25.

Singh S, Facciorusso A, Singh AG, Casteele NV, Zarrinpar A, Prokop LJ, et al. Obesity and response to anti-tumor necrosis factor-α agents in patients with select immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0195123.

Strober B, Gottlieb A, Leonardi C, Papp K. Levels of response of psoriasis patients with different baseline characteristics treated with etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:220.

Gordon K, Korman N, Frankel E, Wang H, Jahreis A, Zitnik R, et al. Efficacy of etanercept in an integrated multistudy database of patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:S101–11.

Menter A, Gordon KB, Leonardi CL, Gu Y, Goldblum OM. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab across subgroups of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:448–56.

Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: psoriasis comorbidities and preferred systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:27–40.

Lebwohl M, Yeilding N, Szapary P, Wang Y, Li S, Zhu Y, et al. Impact of weight on the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: rationale for dosing recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:571–9.

Papp KA, Langley RG, Lebwohl M, Krueger GG, Szapary P, Yeilding N, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 52-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 2). Lancet. 2008;371:1675–84.

Kimball AB, Papp KA, Wasfi Y, Chan D, Bissonnette R, Sofen H, et al. Long-term efficacy of ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated for up to 5 years in the PHOENIX 1 study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1535–45.

Young M, Horn E, Cather J. The ACCEPT study: Ustekinumab versus etanercept in moderate-to-severe psoriasis patients. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7:9–13.

Herrera-Acosta E, Garriga-Martina GG, Suárez-Pérez JA, Martínez-García E, Herrera-Ceballos E. Ixekizumab vs ustekinumab for skin clearance in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis after a year of treatment: real-world practice. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33: e14202.

Megna M, Di Costanzo L, Argenziano G, Balato A, Colasanti P, Cusano F, et al. Effectiveness and safety of secukinumab in Italian patients with psoriasis: an 84 week, multicenter, retrospective real-world study. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:855–61.

Augustin M, Reich K, Yamauchi P, Pinter A, Bagel J, Dahale S, et al. Secukinumab dosing every 2 weeks demonstrated superior efficacy compared with dosing every 4 weeks in patients with psoriasis weighing 90 kg or more: results of a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:942–54.

European Medicines Agerncy. Bimzelx (internet). Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/bimzelx-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Cited 12 Apr 2022.

del Alcázar E, López-Ferrer A, Martínez-Doménech Á, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Llamas-Velasco M, Rocamora V, et al. Effectiveness and safety of guselkumab for the treatment of psoriasis in real-world settings at 24 weeks: A retrospective, observational, multicentre study by the Spanish Psoriasis Group. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15231.

Gerdes S, Bräu B, Hoffmann M, Korge B, Mortazawi D, Wiemers F, et al. Real-world effectiveness of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis: Health-related quality of life and efficacy data from the noninterventional, prospective German multicenter PERSIST trial. J Dermatol. 2021;48:1854–62.

Hansel K, Zangrilli A, Bianchi L, Peris K, Chiricozzi A, Offidani A, et al. A multicenter study on effectiveness and safety of risankizumab in psoriasis: an Italian 16-week real-life experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e169–70.

Mastorino L, Susca S, Megna M, Siliquini N, Quaglino P, Ortoncelli M, et al. Risankizumab shows high efficacy and maintenance in improvement of response until week 52. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15378.

Ritchlin CT, Mease PJ, Boehncke W-H, Tesser J, Schiopu E, Chakravarty SD, et al. Sustained and improved guselkumab response in patients with active psoriatic arthritis regardless of baseline demographic and disease characteristics: pooled results through week 52 of two phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled studies. RMD Open. 2022;8: e002195.

Strober B, Menter A, Leonardi C, Gordon K, Lambert J, Puig L, et al. Efficacy of risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis by baseline demographics, disease characteristics and prior biologic therapy: an integrated analysis of the phase III UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2 studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2830–8.

Iskandar IYK, Ashcroft DM, Warren RB, Evans I, McElhone K, Owen CM, et al. Patterns of biologic therapy use in the management of psoriasis: cohort study from the British Association of Dermatologists Biologic Interventions Register (BADBIR). Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1297–307.

Gottlieb AB, Kalb RE, Langley RG, Krueger GG, de Jong EMGJ, Guenther L, et al. Safety observations in 12095 patients with psoriasis enrolled in an international registry (PSOLAR): experience with infliximab and other systemic and biologic therapies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1441–8.

Ruggiero A, Fabbrocini G, Cinelli E, Megna M. Guselkumab and risankizumab for psoriasis: a 44-week indirect real-life comparison. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1028–30.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

The post hoc analyses and Rapid Service Fee for this manuscript were sponsored by Almirall R&D, Barcelona, Spain.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Mónica Giménez, PhD, and Eva Mateu, PhD, of TFS HealthScience. Support for this assistance was funded by Almirall R&D, Barcelona, Spain.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

DT made a significant contribution to the conception and design of the study, the analysis and interpretation, the drafting of the manuscript and the critical review of it for important intellectual content. SG and KGdJ contributed to the conception and study design and critically reviewed the article. JLP and LLP critically reviewed the manuscript.

Prior Presentation

Part of this manuscript is based on work that was previously presented at the 31st Congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV), Milan, 7–10 September 2022.

Disclosures

Diamant Thaçi has received honoraria as an advisor, speaker and/or investigator from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Biogen-Idec, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Janssen-Cilag, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche-Possay, Samsung, Sanofi and UCB; Sascha Gerdes has been an advisor for and/or received speakers’ honoraria from and/or received grants from and/or participated in clinical trials by the following companies: AbbVie, Affibody AB, Akari Therapeutics Plc, Almirall-Hermal, Amgen, Anaptys Bio, Argenx BV, AstraZeneca AB, Biogen Idec, Bioskin, BoehringerIngelheim, Celgene, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Forward Pharma, Galderma, Hexal AG, Incyte Inc., Janssen-Cilag, Johnson & Johnson, Kymab, Leo Pharma, Medac, MSD, Neubourg Skin Care GmbH, Novartis, Pfizer, Principia Biopharma, Regeneron Pharmaceutical, Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals, Sanofi-Aventis, Trevi Therapeutics, and UCB Pharma; Kristian Gaarn Du Jardin is an employee of Almirall; Jean-Luc Perrot has been an advisor for and/or received speakers’ honoraria from and/or received grants from and/or participated in clinical trials by the following companies: Abbott/AbbVie Inc, Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, Incyte Corporation, Janssen-Cilag Ltd, Johnson & Johnson, LEO Pharma, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, and UCB Pharma; Lluís Puig has received grants/research support from or participated in clinical trials (paid to the institution) by AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanof, and UCB; received honoraria or consultation fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Baxalta, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Fresenius-Kabi, Janssen, JS BIOCAD, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sandoz, Samsung-Bioepis, Sanof, and UCB; and participated in company-sponsored speaker’s bureaus for Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, and Pfizer.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2 trials received approval from local institutional review boards or ethics committees. The studies were performed in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. All subjects provided written informed consent to participate in the studies.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thaçi, D., Gerdes, S., Du Jardin, K.G. et al. Efficacy of Tildrakizumab Across Different Body Weights in Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis Over 5 Years: Pooled Analyses from the reSURFACE Pivotal Studies. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 12, 2325–2341 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00793-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00793-z