Abstract

Ethical cultures, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and sustainability strategies are increasingly being addressed through formal organisational policies and structures. This is evidenced by codes of ethics, conduct, whistle-blowing reporting lines, anti-bribery and corruption policies, and broader stakeholder and environmental engagement strategies. In the United States, corporate ethics managers are responsible for these functions, supported by specific professional and university-level qualifications. However, this is not the case in Australia and Asia where the role appears delegated to human resource personnel in organisations. Human resource management (HRM) is increasingly advanced as a formal profession, yet whether corporate ethics content features as a significant component of the HRM profession is unclear. Expert knowledge is a foundation of a profession along with the duty to act within the limits of that knowledge and expertise. This paper scopes what constitutes professional expert knowledge. It examines corporate ethics expertise and HRM within this context. Major Australian and Asian organisations are examined to verify that HRM Departments, and thus HRM practitioners, are responsible for managing corporate ethics. Given the seniority and strategic importance of this function, the content of selected Masters in HRM and related fields are examined to identify the extent of ethics content. This is considered in the light of the expertise required to manage corporate ethics, and conclusions are drawn whether the HRM discipline is appropriately qualified to manage this function. Finally, recommendations and further research towards advancing the role and function of corporate ethics managers in general are proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Corporate ethics systems, policies, and strategies designed to create and maintain an effective ethical culture are regarded as a normal part of modern organisation governance, leadership, and oversight. Corporate ethics can be defined as the set of shared formal and informal perceptions of procedures, policies, and processes that shape the expectations for appropriate ethical or moral behaviour (Al Halbusi et al., 2021; Mulki & Lassk, 2019; Newman et al., 2017; Teresi et al., 2019). The ethical climate is a significant factor in encouraging appropriate or moral behaviour by employees (Treviño & Nelson, 2021; Valentine et al., 2013). The relationship between an effective ethical culture and appropriate moral behaviour by employees through the use of these formal approaches reinforced through senior executive role modelling is well established (DeConinck, 2011; Ferrell et al., 2021; Forte, 2004; Jaramillo et al., 2013; Schmalz & Orth, 2012; Treviño et al., 2017; Treviño & Nelson, 2021).

In the United States, the corporate ethics function is usually managed by an Ethics and/or Compliance Manager, informed by professional programmes and university training in applied ethics. For example, undergraduate and executive programmes feature at the Centre for Business Ethics at Bentley University in Massachusetts, and Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University, amongst others. Formal professional organisations such as the Ethics and Compliance Officer Association (ECOA) also exist, representing and advancing the interests and knowledge of ethics practitioners, indicative of the strategic importance placed on these organisational roles and functions. It should be noted that the ECOA includes as primary members Chief Ethics and Compliance Officers (CECOs) and general counsels with the responsibility of advancing organisational ethical culture and leadership (ECI, 2022). It refers to Human Resource Management (HRM) as an adjacent function in the activities of the Ethics and Compliance Initiative (ECI, 2022).

Within Australian and Asian organisations, however, despite ethics strategies being evident, formal corporate ethics roles are few, with the function seemingly delegated to HRM departments. In addition, qualifications in applied and professional ethics are almost non-existent across Australia and Asia at university and or college level within HR degree courses. This then raises two interrelated concerns which form research questions of this paper. Firstly, do HRM practitioners manage the corporate ethics function in Australian and Asian corporations? Secondly, do dedicated Higher Education courses specifically provide the requisite theoretical and applied ethics knowledge that would underpin the expertise of HRM practitioners holding the corporate ethics role? A supplementary question is whether there is evidence that the HRM function holds the status of a profession, equivalent to organisations such as ECOA?

The research aims for this paper are:

Firstly, to consider the current structure of the corporate ethics role within a selection of businesses in Australia and South-East Asia. This paper examines selected major private and public sector organisations across Australia and Asia to verify that corporate ethics strategies are present and identify the functional or corporate status of the agents with responsibility for the management of corporate ethics.

Secondly, the paper analyses the professional expertise required to address the role of managing corporate ethics. This constitutes the required expert knowledge that enables informed and effective ethical cultures to be developed through systems, policies, and processes, is also examined.

Thirdly, against the insights developed from the second research aim, the expert knowledge of HRM is analysed in relation to the requirements of corporate ethics practice together with evidence about the professional status of HRM to acquit the role associated with corporate ethics.

Finally, several selected postgraduate qualifications in HRM, and related HR Masters are explored to determine the extent of conceptual, applied, and practical ethics knowledge addressed in these qualifications. These aims fulfil the research questions outlined above.

The contribution of this paper is to identify a prevailing gap in the theoretical and applied ethical knowledge of organisational managers assigned a corporate ethics role. This paper contributes to the discussion of the operationalisation of corporate ethics in organisations:

-

Through analysing contemporary HRM professional practice within an Australian and nominal South-East Asian context to determine if it meets the critical requirement of theoretical and applied ethics knowledge required to effectively manage corporate ethics.

-

Through analysing current Australian HRM post graduate courses and other relevant Master level courses to determine the adequacy of inclusion of requisite theoretical and applied ethics knowledge for effectively managing corporate ethics.

Previous research on the role of HR and ethics in HR, management, and business ethics literature has largely focused on examining practices of HR managers from ethical and professional perspectives. There are very few studies exploring the HR manager’s capacity to identify, address, and respond to the totality of an organisation’s ethical considerations, risks, and dilemmas. Studies have tended to examine ethical dilemmas in the HRM role around issues of compensation, performance, organisation development, recruitment, and selection, (Buckley et al., 2001; Csillag, 2019; Wooten, 2001).

Still, other authors have focused upon the ethical practice of HR managers in considering professional codes of ethics (Ardaugh, 2007; Wiley, 2000). A major contribution by Weaver and Trevino (2001) articulated the need for the impartiality role HRM plays within the organisation context. They argued that HRM needs to play a more prominent role in ethics/compliance management due to the fairness expectations of employees (Weaver & Trevino, 2001). However, they failed to indicate where and how HRM practitioners can build their knowledge and practice of empirical and applied ethics to underpin their competence in fairly resolving ethical and compliance issues and designing fair and ethically informed programmes.

An alternative view of ethical HRM through discourse and lived experience has been presented by de Gama et al. (2012). This perspective supports the concept of impartiality and separateness, argued by Weaver and Trevino (2001), but through aspects of distancing, depersonalising, and dissembling (de Gama et al., 2012). Once again, however, no insight is offered as to how to provide a grounding in the requisite theoretical and applied ethics knowledge.

Extant research on HRM and ethics, though important does not provide insight into the critical issue of whether HRM practitioners have the requisite theoretic and applied ethics knowledge to perform the duties associated with a wider corporate ethics role, such as developing corporate ethics initiatives and responses beyond the specific HR function.

Schumann (2001) has argued for a moral-principles framework for HRM ethics, outlining utilitarian, rights, justice, care, and virtue ethics, whilst considering only the functional domain of HRM. His approach, as with many, fails to consider how and where HRM managers might acquire in-depth theoretical ethics knowledge to effectively interpret an ethical dilemma and decide on an ethical action. Csillag (2019) identifies a more concerning issue in HRM ethical practice, that of moral muteness when confronted with ethical dilemmas. In dealing with HRM issues of dismissal, disciplinary action, recruitment, promotion, and organisational culture, 76 HRM experts reported inconsistency, discriminative practices, and favouritism. The respondents identified their muteness and inaction when confronted with ethical problems was due to a lack of ethics knowledge, ignorance and fear, organisational politics, buck passing, and cynicism about having any capacity to make a difference (Csillag, 2019).

On the question of whether HRM is a profession, thereby underpinning a professional role in ethics and compliance, Ardaugh (2007) indicates that HRM meets some of the recognised criteria of a profession but that there is insufficient evidence to confirm the status of a true profession. He notes of HRM managers that “As managers, their first loyalty is to the organisation in a way that is not professionally sequestered” (Ardaugh, 2007, p. 168). He advocates for a more uniform education, an enforced code of ethics, and a code of practice to improve HRM’s independence of top management so as to move HRM closer to the critical requirements of a profession.

Izraeli and Bar Nir (1998, p. 1189) argue that “an ideal Ethics Officer should have appropriate organizational status, functional independence, professionalism, knowledge of organizational issues, and knowledge of ethics theory”. Llopis et al. (2007) support this view of the Ethics Officer (EO), arguing (p. 6) that the essential requirements of an EO are the following: “having a wide knowledge of the firm, mastering management techniques as well as theoretical and practical issues related to business ethics and, the same as the rest of the senior management, having the hierarchical authority necessary to exert an influence on firm members’ behaviour”. Llopis et al. (2007) also argue that the role should not belong to a functional department such as HRM, since not belonging directly to a functional department can confer more credibility and impartiality. To reiterate, the requirements identified by Llopis et al. (2007) would not be fulfilled by locating the EO within the HRM department of an organisation, since the legitimacy of that role based on requisite knowledge and authority could not be guaranteed.

Research methods

Two different aspects of research on the management corporate ethics were undertaken. The first being a review of literature that examined the concepts of professions and the knowledge and expertise required of corporate ethics managers and those of human resource managers. The second aspect of research involved two secondary data analyses of organisation websites applying content analysis. The research aim here was to determine the functional area under which the corporate ethics function was located. Secondary data analysis through corporate documents and most recently corporate websites is a long-held research tradition in business ethics (Donker et al., 2008; Jose & Lee, 2007; McCraw et al., 2009; Rodriguez-Dominguez et al., 2009; Sharbatoghlie et al., 2013; Stohl et al., 2009).

The research paradigm for this paper is qualitative, whereby analysed information and data were gathered from classic and current literature in the fields of corporate and/or business ethics, professional expertise, and HRM. Through such examination, the researchers sought to make sense of and interpret concepts or phenomena (Creswell, 2013; Denzin & Lincoln, 2011, 2018). Literature-based research methodologies were applied (Lin, 2009), whereby content-driven secondary data analysis was undertaken. Such examination of secondary data sources did not require direct contact between researchers and participants (Bassot, 2022; Hoover et al., 2021; Jaleel & Prasad, 2018; Punch & Oaencea, 2014).

Sampling methods and data analysis approach

The literature review was based on data collected utilising applied searches via multiple databases, accessed via a university library. Key terms related to the two concepts of “professions” and “corporate ethics officer/manager” were searched across multiple data bases, search engines, and key academic and business journals in a wide variety of discipline fields. Table 1 outlines the detailed aspects of this approach to locating and identifying literature relevant to the research. The sampling and analysis approach is consistent with similar research projects aiming to determine dominant and differing aspects of key concepts. The approach was non-probability sampling of a purposive type (Henry, 1990; Patton, 2002; Ritchie et al., 2012; Suri, 2011).

Full texts were examined to identify findings related to the nature of ethics managers and their work. This step can be described as an inductive conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). A similar strategy was used for the identification of expertise and knowledge types required for competence, to establish the obligations of professionals and professions that, in particular, related to corporate ethics and HRM.

An inductive reasoning method was used, moving from the specific to the general (Blaikie, 2007) to identify the professional obligation required of managers who profess expertise, and their duty of care and responsibilities in alignment with the societies they serve to act, within the limits of their level of mastery and expertise (Cohen et al., 2010; Hamel, 2012; Podolny, 2009; Sahlman, 2010; Zadek, 2005).

As identified above, the second category of research involved two separate secondary data analyses of numerous organisation websites, both utilising a form of content analysis. The rationale differed for each data set. The authors, being organisational consultants in the field of ethics, noted a trend extending back well over a decade, for Australian organisations to delegate the corporate ethics function to human resource departments. To verify this phenomenon, medium to large-sized organisations in both public and private sectors were selected using indicators such as the top 50 largest Australian, and top ten largest Singaporean, Malaysian, and Hong Kong companies.

The selection of organisations was also intended to represent a range of industry sectors including educational, transport, mining and resources, retail, professional and advisory, and public sector management. The use of large organisations is consistent with organisational theory that highlights increase size and complexity is managed through the use of formalisation (rules and regulations), complexity as reflected by the creation of functional departments and hierarchical levels, and decision-making systems known as the extent of centralization (Daft, 2021; Robbins & Barnwell, 2006). The sampling approach was based on a rationale that the larger organisations more typically create functional roles such as corporate ethics and have departments such as HRM. The selection of organisations was based on their pre-eminence in the business environment for each national economy as such the purposive sampling method reflected a typical case approach (Patton, 2002; Ritchie et al., 2012).

The approach to this analysis was to examine each company’s website for the existence of corporate ethics, via the search function using terms such as corporate ethics, codes of ethics codes of conduct whistle blowing stakeholder engagement. This typically took the researchers to the specific policy website that listed the organisation ethical strategies. The web page was then examined to identify the department or group with responsibility for this policy. Where this was not explicitly stated, phrases or directions that directed employees to a department or a group for further information were used as an indicator.

The second data analysis undertaken was of university and educational institution websites. The selection of the specific university qualification was informed by two specific criteria. Firstly, the previous organisational analysis verified that human resource departments were primarily delegated the responsibility for managing corporate ethics. Consequently, the authors chose to only review qualifications in HRM or with HRM as a major. As there are a multitude of qualifications in this field in Australian and in Asian universities and colleges, a second criterion was used to identify a specific sample set. Qualifications accredited by the professional body, the Australian Human Resource Institute (AHRI), were selected as its accreditation criteria includes the capability of “ethical practitioner”. Twenty-eight postgraduate courses were identified in Australia from some 43 universities, which is argued to be an appropriate sample, aligned to the research. In terms of qualifications from Asian countries, with no consistent HR accreditation present across selected countries, like qualifications such as Masters in HRM, Master of Science in HRM, MBA (HRM) were identified via internet searches. A smaller group of 5 major universities each from Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong were identified to produce an indicative sample.

The contribution of this paper deals with the theory of corporate ethics as a senior executive function in organisations, the expertise required of that role, and whether HRM as a profession has the necessary expertise to carry it out. The value of this research lies predominantly in the framing of both past and present literature on the topic of corporate ethics and the education of HRM, which to date, has not considered whether HR Managers have the necessary expertise to design, implement, and maintain the range of policies, processes and strategies required to create and maintain an ethical culture. As will be seen in the discussion, much of the literature pertaining to corporate managers and compliance managers were published in the 1990s and 2000s, with little current literature available. Our research effectively contributes to his important field of knowledge by reviewing these roles and responsibilities. Secondly, the literature that examines the relationship between ethics and HRM has to date, focused on the ethical implications of HRM practise, and not whether HRM professionals are sufficiently educated in ethics, morality, and corporate strategies, or how to create a healthy ethical culture. This research addresses this literature gap, providing insight towards more effective corporate ethics and HRM education.

Limitations of the research

Given the approach taken, the authors acknowledge limitations to both the data collected, and the resulting analysis is limited to Australia and selected Asian nations. Though this limits generalisability, it nonetheless provides a contribution to research on corporate ethics. The research method relies on secondary data sources, limited to material published or accessible through organisational websites. Previous research by Hurst (2004) for the Markkula Centre for Applied Ethics comparing EU and US business practices in Corporate Ethics, Governance and Social Responsibility followed a similar secondary research approach accessing corporate websites for data, a similar method of sampling corporate businesses, and a similar data analysis. The present research improves on the methodology applied by Hurst (2004) by considering a larger sample of corporations and a larger sample set of nations in Asia, as compared to those considered within the EU. This achieves a greater degree of robustness for the data sample under consideration. Similarly, the approach taken by Bravo et al. (2012) in a study that explores the relevance of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as an element of the corporate identity of 82 Spanish financial institutions would substantially support this paper’s qualitative methodology for our content analysis and method of data sampling.

In terms of the content analysis of postgraduate courses in HRM and related fields, universities, and colleges often restrict access to detailed weekly content of subjects. The authors therefore relied upon the published outlines of course structures and a list of weekly topics for specific subjects, as available in course descriptions for students as distinct from detailed information regarding the learning outcomes, readings, cases etc., for each topic. This, nonetheless did confirm that ethics was not a prominent topic in any individual course nor in most cases was there evidence of there being a core subject in ethics in courses. Similarly, content analysis of organisational strategies for corporate ethics, or the development of an ethical climate, was limited to available information on organisational websites. The approach of using website-based secondary data for research has been applied in several Journal of Business Ethics articles on organisational ethics. Notable among these are Donker et al. (2008), Jose and Lee (2007), McCraw et al. (2009), Rodriguez-Dominguez et al. (2009), Sharbatoghlie et al. (2013), and Stohl et al. (2009).

Whilst policies were often publicly available, such as codes of ethics, codes of conduct, and whistleblowing systems, detailed information concerning specific individuals responsible for managing corporate ethics, along with their qualifications and backgrounds, were not available. This confirmed that there was no evidence of the presence of a dedicated Ethics Officer or a similar defined role. If the reference was made to HRM involvement in the corporate ethics role, this was taken as confirmation that the corporate ethics role was embedded in a functional department of the organisation. Such cases would fail to fulfil the best practice advice of Llopis et al. (2007) and Izraeli and BarNir (1998).

Literature review

Corporate ethics

The term “corporate ethics” can be used by organisations to refer to strategies used internally to create an ethical culture. According to Treviño and Nelson (2021), ethics is an integral part of the organisation’s overall culture, while designing an ethical organisation refers to systematically analysing all aspects of the organisation’s structure and culture, aligning them so that they support ethical behaviour while also discouraging unethical behaviour. This can be termed the “institutionalisation of corporate ethics”, a multi- faceted approach that “main streams” concerns regarding the ethical issues facing organisations (Ferrell et al., 2021; Sampford, 1994; Segon, 2007). Many ethical theorists and researchers have developed approaches which detail the components of an organisational ethical framework enabling ethical cultures to develop. Such strategies include codes of ethics and conduct, ethics training, ethical leadership, role modelling, internal reporting structures, anti-bribery and anti-corruption, and minimising conflicts of interest (Asgary & Li, 2016; Bice, 2017; Charlo et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2001; Nave & Ferreira, 2019; Painter-Morland, 2015). Hogenbirk and van Dun (2021) suggest that these strategies have remained relatively unchanged for many years in terms of developing ethical climates through formal mechanisms.

Driscoll and Hoffman (2000) suggest that whilst ethical responsibility should be assumed by all members of the organisation, the coordination and management of the system designed to establish, inform, and maintain those standards need to be seen as a separate function. Adobor (2006), Ferrell et al. (2021), Hogenbirk and van Dun (2021), and Kaptein (2015) stress the importance of having a senior executive in charge of the ethics programme to ensure effectiveness and ethics is managed like any other corporate function characterised by a structured approach.

The corporate ethics officer

The terms “corporate ethics officer”, “compliance manager”, and more recently “corporate social responsibility (CSR) manager” and “corporate sustainability manager” are being used interchangeably, often referring to the same function (Fu et al., 2020; Strand, 2014; Velte & Stawinoga, 2020). However, the authors take the position that whilst these areas all relate to issues of ethical governance, they are in fact separate corporate functions and roles. Corporate ethics, as defined above, has a specific internal focus regarding the behaviour and standards of all employees through systems and processes such as codes and ethics training for decision-making to develop an ethical climate or culture. CSR is a broader concept that addresses the ethical and legal responsibilities of organisations extending to external stakeholders and the broader society. Whereas sustainability includes aspects of environmentalism, social justice, and sustainable utilisation of resources.

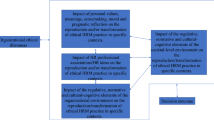

The function of the corporate ethics officers involves specific roles and responsibilities as well as several characteristics that are necessary for effective performance (Adobor, 2006; Driscoll & Hoffman, 2000; Izraeli & BarNir, 1998; Llopis et al., 2007; Segon, 2007; Treviño & Nelson, 2021). Adobor (2006) argues that the role is unique in the organisation, in that it faces multiple and competing expectations from internal and external organisational stakeholders. It requires expert knowledge in distinct areas. Firstly, this entails an advanced understanding of management at senior levels, i.e., a strategic orientation, knowledge of the organisation, its structure and functions, and its external environment, and an ability to engage with stakeholders (Collins, 2009; Hetmański, 2018; Llopis et al., 2007; Segon, 2012). Secondly, it involves expert knowledge in moral awareness and ethical theories, and practical expertise in resolving ethical dilemmas (McNamee, 1991). Ethics is a foundational competency, and managers and leaders cannot be expected to make ethical decisions or devise ethical processes without an understanding of ethics conceptually and practically. Izraeli and BarNir (1998) state that this is typically mastered through expert knowledge and learning (Orme & Ashton, 2003; Segon et al., 2019; Segon & Booth, 2015). This emphasises the need to acquire expert knowledge in theoretical and practical issues related to business ethics, rationalism, decision-making, morality, cognitive moral development, and increasingly, CSR, sustainability, and governance issues.

Corporate ethics managers are required to undertake a multi-duty role that includes: the managing of internal reporting systems; assessing areas of ethical risk; monitoring adherence to codes of ethics and or conduct; overseeing the ethics communication strategies; developing and interpreting ethical policies; overseeing training and development in ethics; and collecting and analysing salient data and reporting to senior executives (Adobor, 2006; Collins, 2009; Segon, 2012).

From within these role definitions, directives, and descriptions, one can clearly identify necessary expert skill areas such as strategic management, including organisational structure and design, policy development and implementation, managing change, internal advocacy and communication regarding ethical standards, and a broad knowledge of external factors including legal requirements. Such role aspects are readily related to bodies of expert strategic business skills and knowledge. These include the capacity for significant reflection and analysis as to what is moral or ethical; decision-making approaches that extend beyond financial perspectives, utilising a variety of ethical traditions, including but not limited to Kantian, Aristotelian, and Utilitarian ethics. In addition, an in-depth understanding of compliance, regulation, laws etc., and of traditional management and organisational concepts is required.

Given that this expertise rests on philosophical traditions and on bridging these to business knowledge, we advance that this breadth of knowledge is abstract in nature and aligns with Freidson’s (1970) description of “pure knowledge”, resting largely on theory and a form of practical knowledge that guides the professional’s application. The need for such understandings further aligns with the argument that the professional must be able to combine or integrate knowledge and apply this abstraction to identify and redefine problems and develop strategies for resolution (Mangham & Pye, 199; May, 1989). We also suggest that the corporate ethics manager would more likely acquire this combined body of expert knowledge formally in universities through qualifications that address business, management, HR, philosophy, and business ethics in addition to stakeholder analysis and engagement. This brief overview of the role of a corporate ethics officer clearly suggests that a substantial and significant body of expert knowledge is required to adequately fulfill their role and for decisions to be made, whereby a degree of seniority if not executive-level experience would be expected and/or required. In the United States, the Society of Corporate Compliance and Ethics (SCCE) provides certification examinations towards national and international levels of professional accreditation (SCCE, 2024). It also recognises the degree qualifications of 16. US universities towards professional certification (SCCE, 2024).

Expertise, knowledge, profession, and professional practice

The foundation of professional practice is an expectation of competence in the ability to apply expert knowledge (Chadwick & Thompson, 2000; May, 1989; Segon et al., 2019). Traditionally, a profession has been identified by mastery of a specific body of expert and theoretical knowledge, and by a substantial skill base that is acquired after lengthy education, inclusive of testing for competency (Chadwick & Thompson, 2000; Hetmański, 2018; May, 1989; Segon et al., 2019; Thu, 2016). According to Abbott (1988, p. 20), professions are exclusive occupational groups applying “abstract knowledge” to cases and having “jurisdiction” that is the authority and dominion over the field as the link between a profession and its work. Barker, (2010) and Martin, (2000) describe professionals as relying on information asymmetry, whereby the expert practitioner must have a high degree of knowledge and expertise, either in the sense of superb technical skill, or in the form of extensive specialist knowledge, or some amalgam of both (Sellman, 2012). However, expert knowledge takes different forms, with theory and application being discrete aspects.

Professional knowledge is accepted as encompassing two types. The first aligns with Freidson’s (1970) description of “pure” knowledge or a type of codified science, being the ability to engage in rational deduction, use of logic, and analysis, that is founded on a substantial theoretical framework (Cheetham & Chivers, 2001; Mangham & Pye, 1991; May, 2001; Segon et al., 2019). It is considered being substantial, complex, acquired through formal learning, and linked to professional accreditation practices and expectations, and the expertise of practice (Canós-Darós et al., 2008; Eraut, 2000; Peris-Ortiz & Merigo, 2015).

The second type is behavioural knowledge, described as the tacit and intuitive understanding required for engagement. Considered abstract in nature, this knowledge distinguishes the professional from other individuals and groups being closer to talent, basically formed by attitudes, skills, and unencrypted abilities (Canós-Darós et al., 2008, p. 1908). In terms of a profession, explicit knowledge is considered the technical know-why, and tacit knowledge is more akin to know-how in application, while in combination they constitute practice requiring insight (Canós-Darós et al., 2008; Peris-Ortiz & Merigo, 2015).

The professional can thus combine or integrate these two forms of knowledge and apply this compound abstraction to problems, redefining them and the tasks required to solve them (Canós-Darós et al., 2008; Mangham & Pye, 1991; May, 2001). The specific explicit knowledge of an expert and the insight and attitude of tacit knowledge that supports and underpins expertise of practice.

This complex and esoteric body of expert theoretical and practical knowledge extends beyond mere training to education and development (Lusch & O’Brien, 1997; May, 1989). A profession requires extensive lengthy education with a formal qualification, based in a university, distinguishing it from apprenticeship and the crafts (Flexner, 1910; Winch, 2004). May (1989) further states that a function of the professional is to contribute to the body of knowledge, through further research. Although all professionals need not be researchers, the profession must lay the foundation for the advancement and progress in the field, again typically at a university.

The existence of an association that represents members and the interest of a discipline is advanced as a key characteristic that differentiates a profession from an occupation (Ardaugh, 2010; Dellaportas et al., 2005; Khurana et al., 2005; May, 1989). These representative bodies undertake a variety of functions (Khurana et al., 2005; Segon et al., 2019). These include:

-

Developing rules or standards to which members must abide

-

Clarifying the level of mastery required of its members

-

Advancing the expert knowledge of the profession

-

Restricting membership to only those that satisfy the standards of practice

-

Regulating the behaviour of members

-

Having a licensing and/or accreditation system for members and organisations

Professional competence is argued as being the ability to perform specific tasks and skills, informed by expert conceptual knowledge (Sellman, 2012). This can be described as “professional phronesis”, or a practical wisdom that professionals must acknowledge both as a restriction and a requirement of their licence to practice. Sellman (2012) argues that professionals must have an ethical foundation, in particular virtues such as honesty and trustworthiness, to ensure informed and intentioned actions which do not cause harm.

The authors advance that the body of knowledge required to design, implement, maintain, and evaluate corporate ethics needs to be assessed and distinguished as either part of, or separate from the “profession” of HRM and management in general. Only once this analysis has occurred can inferences be drawn regarding the appropriateness of Human Resource Departments and/or HR practitioners to assume responsibility for corporate ethics.

HRM as expert knowledge

The term HR profession is being increasingly used suggesting that the discipline has attained or is moving toward true professionalisation (Armstrong, 2022; Losey et al., 2005; Ulrich et al., 2013). Losey (Losey, 1997, p. 147) explicitly claims that “human resource management is a profession”. The notion that HRM is both a professional and academic discipline is based on the achievements of psychology and economics, among other fields, and invokes numerous theories such as leadership (Iqbal & Ahmad, 2020), motivation (Kollmus & Agyeman, 2002), and stakeholder theory (Ferrary, 2009). Jucius (1975) defines HRM as an area of management that addresses planning, organising, and controlling the functions of acquiring, developing, maintaining, and utilising employees such that organisational and individual goals are achieved. HRM is directly concerned with attracting, motivating, rewarding, and retaining employees (Bolman & Deal, 2021; Dessler, 2015; DuBrin, 2022; Martocchio, 2020; Nel et al., 2016; Van Buren & Greenwood, 2013). More recently, HRM has been defined as “the adoption of HRM strategies and practices that enable the achievement of financial, social, and ecological goals, with an impact inside and outside of the organisation and over a long-term time horizon while controlling for unintended side effects and negative feedback” (Ehnert et al., 2015, p. 90).

An analysis of literature regarding the knowledge required of HR practitioners reveals two bodies of critical expertise, being functional HRM and strategic HRM (Bailey et al., 2018; Lo et al., 2015; Tyson, 2015; Ulrich et al., 2013). Functional or operational HRM refers to the policies, practices, and systems that influence employees’ behaviour, attitudes, and performance (Noe & Winkler, 2009). These include an extensive range of activities such as human resource planning; job analysis and design; recruitment, selection, induction, and dismissal of employees; performance management and compensation; training and development; career and succession planning; labour relations, health, safety and fairness concerns; industrial and employee relations and, associated personnel administration (Bolman & Deal, 2021; Dessler, 2015; DuBrin, 2022; Martocchio, 2020; Nel et al., 2016).

Strategic HR involves designing and aligning HR policies and processes with business or corporate strategies to achieve advantage over competitors, given the external environment and its capabilities (Lo et al., 2015; Tyson, 2015). Lo et al. (2015) and Ulrich et al. (2013) describe a range of higher order competencies that enable strategic HR including credible activism, capability building, change championing, HR innovator and/or integrator, and technology proponent abilities. These are examples of practical and tacit knowledge (Lusch & O’Brien, 1997; May, 1989), on which the professionals depend for engagement (Canós-Darós et al., 2008; Mangham & Pye, 1991; May, 1989). They align with a range of input-based competencies, also referred to as emotional intelligence, as described by Boyatzis (1982), Hellriegel et al. (2008), Salovey and Mayer (1997), and Segon and Booth (2015). More recently, the need for high levels of moral and ethical standards, considered fundamental in building organisational climate has also been identified (de Gama et al., 2012; Greenwood, 2013).

We acknowledge that the significant body of knowledge and expertise, both conceptual and practical in nature required for HRM is consistent with “scientific knowledge” and “behavioural knowledge” as described earlier (Abbott, 1988; Cheetham & Chivers, 2001; Eraut, 2000; Gold et al., 2002; Mangham & Pye, 1991; Segon et al., 2019). The knowledge required to undertake the functional roles of HRM, such as recruitment, selection, and job design, are consistent with Sellman’s (2012) position, that specific tasks and skills termed “professional competence”, are informed by conceptual and scientific knowledge through rational deduction, use of logic, and analysis (Cheetham & Chivers, 2001; Mangham & Pye, 1991; May, 1989; Segon et al., 2019).

HRM and organisational ethics

de Gama et al. (2012) identify a relationship between the ethics and HR functions such as acting as ethics advocates, and the need to utilise broader moral and ethical philosophies, rather than only a traditional justice-based ethical framework when dealing with employees. Treviño and Nelson (2021) note that within many organisational structures, the ethics/CSR function is located within HR, audit, or legal departments. They suggest this leads to a perception that ethics/CSR is considered a functional task rather than a holistic corporate strategy. Equally, the secondary data research conducted for this paper confirms this relationship across four different countries further establishing the validity and consistency of the observation. Wood (1997) suggests that the HR function includes a role of ethical stewardship, involving raising awareness about ethical issues, promoting ethical behaviour, and disseminating ethical leadership practices amongst leaders and managers and stimulating debate. Woodd (1997) further included communicating codes of ethical conduct, devising, and providing ethics training to employees, managing compliance, and monitoring arrangements, and taking a lead in enforcement proceedings. Woodd (1997) argues that this requires a degree of “expertise”, emphasizing the need for continuing professional development shared by the professional association. However, she does not make clear whether continuing professional development provides sufficient strategic and conceptual ethics knowledge, characterised earlier as required of ethics officers.

Researchers have examined the ethical implications of recruitment and selection, training and development, or employee termination, using a range of moral and ethical perspectives (Van Buren & Greenwood, 2013). However, the educational focus of HRM does not explicitly address, incorporate, or integrate ethics into current HRM courses (Bowman & Menzel, 1998; Greenberg, 1987; Wells & Schminke, 2001; Van Buren & Greenwood, 2013). More recent trends evident in academic literature are to examine the role of HRM through the lens of social responsibility and sustainability (Cohen & King, 2017; Santana et al., 2020; Shen & Zhang, 2019). Notwithstanding these recent analyses, there appears to be little if any literature that examines what ethical conceptual knowledge is required by HR practitioners, to be cognizant of the ethical dimensions of the policies and procedures that they are designing. We argue that this absence leads to failure to equip students and thus practitioners of HRM with a sufficient understanding of business and corporate ethics to undertake the corporate ethics function.

HR as a profession and AHRI

As noted earlier in this paper, the existence of a professional body that has numerous responsibilities is also a key distinguishing feature of a profession, scoping the conceptual knowledge of the discipline and establishing standards of practice for its members and the general community. The Australian Human Resource Institute (AHRI) promotes itself as the body that represents HRM professionals in Australia. Its relevance to this research is not only as a representative body but also via its “HR Framework” that details the competencies required of HR practitioners for certification, and of educational institutions seeking accreditation for their courses addressing HR. AHRI (2023) states, that “as the professional association for HRM, AHRI is tasked with ensuring HRM professionals and people managers have the essential prerequisite skills and knowledge required to work in the HRM profession”.

According to ARHI, “ethical practice” is a specific capability that appears under its Culture and Change Leader category of the framework. Ethical practice is described as a capability which enables the practitioner to provide valued insights, and the ability to influence ethical behaviour to achieve individual and organisational objectives (AHRI, 2023).

AHRI’s description of ethical practice clearly identifies that practitioners need to understand ethics and morality, use various ethical theories to make ethical decisions, and comprehend issues of conflicts of interest, etc. This clearly assumes that the HRM practitioner can design policies and processes for ethics and integrity, demonstrate ethical leadership, and provide expert guidance and advice to the organisation regarding ethics and integrity.

We argue that this range of ethical capabilities suggests the need for a substantial amount of conceptual knowledge in various aspects of philosophy, including utilitarianism, deontology, Aristotelian ethics, and how these are used to justify decisions. Policies for employment such as equal opportunity and following key criteria in selection are necessarily informed by ethical principles of justice, fairness, and rights. The issue is whether HRM practitioners are merely taught to follow the laws as distinct from being educated in their moral foundation.

AHRI also accredits undergraduate and postgraduate courses at Australian education institutions based on two criteria:

-

(1)

Internal quality assurance processes with continuous improvement; and

-

(2)

The academic course will equip a graduate to meet the desired accredited HR course outcomes (AHRI, 2023).

The logical implication of this substantial amount of knowledge, is that it should be an identifiable and recognisable component of formal learning. We argue that this requirement would be consistent with the description of “scientific knowledge” and “behavioural knowledge” expected of a profession as previously noted (Abbott, 1988; Cheetham & Chivers, 2001; Eraut, 2000; Gold et al., 2002; Mangham & Pye, 1991).

As noted in the research methodology, given that the AHRI’s HRM Framework identifies “ethical practice” as a specific competency or learning outcome, accredited courses were analysed to establish the extent of ethical content in the core or compulsory part of the qualification. As argued earlier in this paper, the corporate ethics role would ideally be located at a senior level. Thus, post-graduate qualifications should have more substantive and in-depth conceptual content and remain the focus for this analysis.

Organisational ethics in Asia Pacific organisations

As identified in the research method section, a review of major corporations and public sector organisations in Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong indicates that most espouse to be addressing corporate ethics and external stakeholders using codes of conduct, codes of ethics, whistleblowing systems, and a stated commitment to sustainability goals.

Over 50 Australian organisations were examined through specific individual searches (summarised in Appendix Table 3). Of the 31 private sector organisations examined, a code of conduct was identified in 93.5% of cases with the HRM Department or a variation thereof (People Services, People and Culture, etc.), identified as either the owning department or the point of contact for further details or reporting in 74% of cases. Risk and/or Governance accounted for 5 organisations or 6%, and 3 were unclear as to who to report to, or how to seek further information about the ethics policies or procedures. One firm had a dedicated Ethics Manager identified for further contact and another referred to an “ethics champion” alongside HR.

In the case of the 15 public sector organisations, all had similar documents called codes of conduct, and HR or People and Culture departments, etc. appeared to serve as the main contact point in all cases. The possession of ethics codes is a mandated requirement in Australian Public Sector organisations. For example, in the State of Victoria, the Victorian Public Sector Commission, has established additional guidelines that most public sector organisations adopt as the Victorian Public Sector Code of Conduct. An interesting observation by the authors is that the term “code of conduct” is used synonymously for documents that include proscribing acceptable or unacceptable conduct, aspirational statements, and statements of values or ethical principles. In addition, most of the documents were comprehensive, with details of Anti-Corruption, Bribery, Conflicts of Interest, and Whistleblowing policies. Consequently, they were lengthy publications between 5 and 15 pages, and of a high production value with photos, logos, and colourful layouts.

In the Asian context, the same approach to analysis was undertaken, whereby the top listed companies in Hong Kong and Singapore, along with selected companies in Malaysia were examined. As can be seen from the findings (see Appendix Table 4), an ethics code document was identified in all organisations. However, there was greater variation in the names of the documents, with the Code of Conduct being used in 9 of the 11 companies examined in Hong Kong, and HR being identified as the contact point, and Risk or Legal being the other department most often referred to.

In Singapore, Codes of Conduct were identified in 10 of the largest organisations, with two referring to HR and three having Ethics or Integrity Sections, with the remainder referring to Governance and/or Audit. In two organisations, the documents contained no link or point of contact. In the Malaysian context, five of the largest organisations were reviewed, with two organisations having codes of conduct, two a code of conduct and ethics, and one having a code of ethics. Two organisations directed employees jointly to the HR and Legal Departments, one identifying Audit, and one to Ethics and Governance. Interestingly, these tended to be predominantly office or word documents and lacked a glossy or attractive presentation. They also tended to be more succinct at 1–2 pages in length. We infer that these are more functional in nature and do not relay on layout, photo graphics etc., as a way of making them more appealing to employees.

The authors noted that in most documents across the Asian countries, advice firstly directed employees to discuss matters of concerns with their immediate superior or department head. In most documents, it was difficult to identify specific reporting mechanisms and, in some cases, whilst hotlines or whistleblowing systems were mentioned, no direction or links were provided for reporting or where to seek further advice.

A review of the analysed data across these countries confirms that organisations are utilising ethical policies to guide behaviour, predominantly linked to HR departments, followed by audit and governance, with relatively few dedicated ethics and integrity units. As noted earlier in this paper, no substantive qualification in applied or corporate ethics was identified in Australia, Singapore, Malaysian, or Hong Kong universities. The question again arises whether the HR profession possesses sufficient expertise, knowledge, and capability in business ethics, as reflected in formal HRM and Management qualifications, to ensure an informed approach to the creation, development, and maintenance of effective corporate ethics.

The role of the Asia Pacific Federation of Human Resource Management (APFHRM)

The APFHRM acts as the umbrella organisation for individual national HRM institutes that are the professional bodies of each member nation. The APFHRM consists of seventeen national body members similar to AHRI. APFHRM objectives are to:

-

Serve as the umbrella organisation of all human resource institutes within the Asa Pacific region

-

To improve the quality and effectiveness of professional human resource management in the region

-

To encourage and support human resource managers in creating and developing their own association in Asia Pacific countries where they do not yet exist

-

To provide guidance and assistance to all member countries especially with regard to their programmes that will uplift the human resource management profession

APFHRM also maintains values of professional responsibility and accountability, professional fairness and consistency, and professional development upholding the values of each individual national HRM institute. However, no specific reference is made to ethical practice nor to the ethical principles that underpin professional responsibility and accountability.

A study of accredited Masters in HRM and IR across the Asia Pacific region

The authors examined all AHRI’s accredited post-graduate courses as the basis for the Australian sample for this analysis. The rationale for this research decision was based upon: Master level courses represent an elite specialist qualification frequently sought by students for professionalisation (Brown et al., 2016); Master are predominantly focused on critical and core study areas for mastery of study (Ott et al., 2015); faculties present their Master courses as flagships in specialist areas of professional study (Stork et al., 2015).

In the case of universities in Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong, a sample of similar Master level courses was examined, and professional accreditation standards in the meeting of national or international accreditation standards were noted. We reiterate that AHRI includes ethical practitioner capabilities as being outcomes of the courses it accredits. We therefore expected to identify specific and substantial content in business ethics, in addition to specific cognate HRM content as core or compulsory subjects. This would signify that graduates acquire an informed foundation for expertise in corporate ethics. Again, the sample considered postgraduate Master level courses based upon the sample rationale given above.

To understand the breadth of content addressed in the core of Masters of HRM (and industrial or employment relations), these qualifications were examined, identifying units or subjects by name and theme to highlight cognate areas. As summarised in Table 2, the most frequent subjects addressed were Employment or Industrial Relations and Strategic HRM, each of which was evident across 86% of qualifications. Excluding Organizational Behaviour and general or introductory HR subjects, these were followed by Compensation and Remuneration at 60%, Change and Corporate Transformation at 53%, HR Analytics at 53%, International HRM at 46%, Recruitment and Selection at 46%, Negotiation and Conflict Resolution at 40%, Diversity at 20%, and Law and Legal Issues at 20%. Of the AHRI accredited Masters, Business Ethics subjects accounted for only 1.3% of content with another 0.6% for Professionalism or Professional Practice subjects. Interestingly, the more recently advocated capabilities of resilience, self-awareness, empathy, influence, etc., that enable roles such as strategic HR positioning as previously described (Lo et al., 2015; Ulrich et al., 2013) are not identifiable as discrete subjects.

The content across these qualifications focuses predominantly on reinforcing functional or operational HRM knowledge consistent with the scope with limited attention to strategic aspects and negligible content in ethics (Bolman & Deal, 2021; Dessler, 2015; DuBrin, 2022; Martocchio, 2020; Nel et al., 2016; Van Buren & Greenwood, 2013).

Ethics content in HRM and MBA qualifications across the Asia Pacific region

The second content analysis was to review the same Master courses to establish the prevalence of required subjects in ethics as identified by title, including business ethics, management ethics, ethics and sustainability, ethical leadership, ethics, and CSR, and in some cases, accounting or finance and ethics.

Australian university accredited qualifications: results

As of May 2023, a total of 25 Australian Universities or Colleges were identified as having 28 AHRI accredited post graduate qualifications (see Appendix Table 5). Altogether, 15 were Masters in HRM and Industrial Relations; five Masters of Management with a stream in HRM; three MBAs with streams in HRM; three Masters of Business; one Master of Commerce; and one Master of Organisational Leadership. Review findings indicate the following. The 15 accredited Master of HRM courses displayed similar structures and content, with eight most commonly being compulsory subjects addressing Employment or Industrial Relations, Strategic HRM, HR Planning Recruitment and Selection, Training and Development, Organisational Change, etc. This is to be expected given the accreditation system used by AHRI, yet also consistent with the description of expert or conceptual knowledge required of professionals (Chadwick & Thompson, 2000; Curnow & McGonigle, 2006; Thu, 2016).

Common structures and subject matter were also evident in the MBAs, although featuring a broader and more generalist core, including Strategy, Marketing, Economics, Finance, and Accounting, and between one and to two subjects in Management and Leadership. The respective Masters of Management, of Business, and of Commerce were similar to, and at times indistinguishable from, MBA structures. These generalist Master programmes typically offered four major subjects in HRM that could also be awarded as a separate graduate certificate.

Based on the published data, only three universities and one private college have an AHRI accredited Masters that have a compulsory subject in Business Ethics. Of the 28 AHRI-accredited courses, only 5 require a subject in Business Ethics or CSR to be taken as core. These are:

-

The University of South Australia requires students to complete the unit, Business Ethics as part of its MHRM.

-

Victoria University requires Business Ethics and Sustainability as part of its MHRM.

-

The University of New England uses the same ethics course for both of its approved MHRM and MBA; and

-

Wentworth College (Private College) requires students to undertake Business Ethics as part of its Master of Management.

Two universities use the term “Sustainability” as part of a required subject being: Latrobe University, with the subjects of Sustainable Innovation and Sustainable Marketing; and Monash University, with the subject of Sustainable Innovation. Queensland University of Technology (QUT) has a core unit with an ethics-related term in its title “Responsible Enterprise”, as part of its MoB (HRM).

A review of the ethics subject descriptions at the Universities of South Australia, Victoria and New England reveals a general introductory subject that includes weekly topics on ethical theories, moral responsibility and accountability, ethical decision-making, CSR, sustainability, international business ethics, etc. The objective of these subjects appears to be introducing the broad spectrum of business ethics and CSR, and not providing substantive in-depth knowledge of the sort of content identified above regarding the expertise required of corporate ethics officers.

A review of the programmes listed in Appendix Table 5 indicated that 82% or 23 of the AHRI Accredited Master programmes contain no identifiable ethics content as a required or standalone subject of the qualification. Notably, 14 of the accredited programmes did not identify any electives that included business ethics or related fields.

We argue that based on this analysis, the 28 accredited AHRI Australian Masters courses in HRM or Management with HRM specialisations do not provide sufficient substantive ethics content that aligns with the conceptual expert knowledge required of corporate ethics officers. An issue clearly arises regarding the capability framework of the professional body, AHRI, and the associated learning outcomes of ethical practitioners at 4 levels of knowledge. A basic premise of education design and learning needs is that learning outcomes must be achieved via specific content, utilising appropriate education design for delivery with an authentic assessment to evaluate whether it is attained. Based on the analysis of accredited master’s courses, there is little if any conceptual, theoretical, or practical attention given to the substantial content of business ethics, moral reasoning, etc. We argue that is almost impossible for a student of these Masters courses to acquire a basic understanding of ethics, let alone the depth and breadth required of the corporate ethics function. Furthermore, even the five Masters programmes that do include a subject in ethics cannot be advanced as developing in-depth content on par with the cognate disciplines of HR and general management that remain the intended focus of those qualifications.

The authors are impelled to pose a further question of the accrediting body, representing the HR “profession.” How can it accredit qualifications using its HR Framework that includes “ethical practitioner” as an outcome, if no or negligible business ethics content is required?

Asian university HR qualifications: results

As with the Australian analysis, searches were conducted for Masters courses focusing on HRM in Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong (see Appendix Table 6). In Singapore, two Masters of Human Capital, one MSc in Human Capital, one MBA (Global Talent/HR) and a Research Top Up Master (in HR) were examined. In Malaysia, four universities offered Masters of HRM and one and MBA with HRM concentration. Hong Kong, two MSc, one Master of HRM, one Master of Management and one Master of Business were identified. Out of curiosity, one MBA (HRM) in the Special Autonomous Region of Macau was also examined.

Among the five Singaporean Universities, two had required subjects in Business Ethics and/or CSR, and the Singapore National University’s MSc included a subject in Employment Law, Policy, and Ethics.

In Malaysia, of the five universities examined, none required a subject in business ethics, however, in the case of the University Putra Malaysia, a subject called Responsible Enterprise was required. At the University of Malaya, a Business Ethics and Corporate Governance unit was identified, but only as an elective. As such, there is no guarantee that these students would complete this subject.

Across the five universities in Hong Kong that were analysed, two programmes had subjects on ethics that were identified as compulsory. One subject was Business Ethics in HRM at the Hong Kong Baptist University, the other was Business Ethics in the MHRM at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. The City University of Hong Kong also has a compulsory Corporate Governance and CSR subject that addresses similar content. At the University of Macau, an MBA with a concentration in HRM is offered that includes a compulsory subject in Ethics and Leadership. Like their Australian counterparts, these subjects primarily provide a general introduction to business ethics and ethical theories. Some subjects contain more specialist content examining Ethical Leadership or Governance, but rarely do these exceed one weekly topic. As such, there is no evidence in any of these HRM or general management qualifications to examine the substantive body of conceptual and practical knowledge required of corporate ethics managers.

As noted in “Organisational Ethics in Asia Pacific Organisations” section, about organisations across Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong, the responsibility for managing the ethics function tends to be located within HRM departments, although this tendency is not quite the same level as in the Australian counterparts, as audit and legal feature in some 30% to 40% of cases. All in all, given that no significant applied ethics qualifications were identified in the three Asian countries, the findings from the examination of Masters in HRM, Master of Science and MBAs parallel the Australian evidence of there being little, if any, required content in ethics, corporate ethics, and related fields. Like the Australian qualifications, those Masters courses with business ethics content, usually provided as only one subject, typically constitute 10% of overall content, are introductory and cannot be regarded as substantial in nature.

These findings clearly support the view that the current practise of delegating responsibility for corporate ethics and related practises to HRM professionals is likely to lead to ineffective outcomes. Furthermore, if HRM is to be considered a profession, then members of the profession are bound by a duty to act within the limits of their knowledge. Professional phronesis requires an acknowledgement both as a form of restriction and as a requirement of their licence to practice solely based on their expertise (May, 1989; Segon et al., 2019; Sellman, 2012). The absence of any significant component of conceptual and practical knowledge related to business ethics in these qualifications suggests that not only are HR managers not qualified to undertake the responsibility for corporate ethics but that doing so with such limited training is a violation of their duty as HR professionals. As identified earlier in this paper, this does not mean that HR professionals or managers with MBAs with HRM majors cannot acquire this knowledge. However, currently, there is no formal postgraduate qualification at either graduate certificate, graduate diploma, or Masters level that sufficiently addresses the topic of corporate ethics.

Conclusions and recommendations

This paper has presented qualitative research that outlines the increasing importance of corporate ethics within organisations across Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia. It has demonstrated that in most cases, responsibility for managing this function appears to predominantly reside with HRM practitioners. Literature has been presented that demonstrates that the key characteristics of a profession include requiring a body of expert knowledge to be formally acquired at a university, with accreditation managed by a formal association that stipulates a professional duty to limit practise to only that expertise and knowledge. Our research has demonstrated that the typical qualifications for senior HRM and management qualifications such as Master of HRM, MBAs, and Master of Science in Management or HRM do not currently contain the substantial body of knowledge identified as required of corporate ethics managers or practitioners.

Simply put, this research has demonstrated that senior managers with HR or Management qualifications, based on the analysis of the content of their qualifications do not possess sufficient conceptual knowledge to devise, manage, and implement corporate ethics. It can also be argued from the perspective of professionalism and the limits to practice that without the necessary competence, accepting responsibility for managing corporate ethics is a violation of professional duty. It also appears that the primary Australian professional HR association accredits courses, implying substantial ethical learning outcomes, even though little if any substantive ethics content is identifiable.

We argue that further research should be undertaken to identify a representative sample of practitioners or corporate ethics officers, to determine whether they hold additional qualifications in corporate ethics or have undertaken training and development to address this apparent knowledge gap. We also posit that our research demonstrates a need for a specific qualification in corporate ethics, which could ideally form part of a stream or major in courses such as masters of HRM or MBAs. It is argued that such content should comprise separate and discrete subjects in areas such as designing ethical policies, ethical theories which inform decision-making, understanding the role of ethical climate, and international perspectives on business ethics. This is in addition to legal aspects and the integration of ethics with other related functions including financial, auditing, risk management, and the important roles that HRM plays, such as training and development in ethics, and ethical leadership. It is also clear that such further research should involve both Australian and Asian practitioners to assess corporate ethics practices across the Asia Pacific business sector.

We further argue against the concept of embedding this content in existing subjects or programmes such as marketing, HRM, and information technology based upon the following limitations inherent in present academic practice. Many business academics are either professionals, such as lawyers, engineers, doctors, or are functional specialists such as company leaders, and marketing managers, who entered academia to share expert knowledge (Segon & Booth, 2010). Accordingly, we recognise that many educators do not necessarily have a background in teaching nor sufficient expertise in ethics to deliver such training in ethics, CSR, ethical corporate governance, etc. Sims (2002) states that the embedded approach to business ethics and CSR puts many academic faculty in the uncomfortable position of teaching outside their specific discipline specialty. Weber (2006) stresses the importance of the facilitator in enhancing ethics education, stating that informed and well-prepared facilitation is critical for success. Dean et al. (2007) in a review of faculty teaching preference, did not find an enunciated interest in teaching ethics. Alsop (2006) argues that ethics training may be flawed because the application of ethical cases and topics within functional subjects may not be based on a fundamental understanding of the conceptual knowledge required to conduct ethical analysis when delivered by those outside the ethics/CSR profession. For such reasons, we argue that a separate and robust set of subjects needs to be developed that address the necessary conceptual knowledge, the pure and scientific knowledge, and the behavioural knowledge previously identified as fundamental to mastery and expertise within the management of corporate ethics.

Finally, we argue that there is a need for AHRI to address this clear knowledge gap amongst members of its profession. We suggest that if AHRI continues to accredit both individuals and courses as having developed ethical competence, without having undertaken any substantive ethics education, a significant ethical and reputational risk is evident.

References

Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labour. University of Chicago Press.

Adobor, H. (2006). Exploring the role performance of corporate ethics officers. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 57–75.

AHRI (2023). Australian Human Resource Institute website at https://www.ahri.com.au/about-us accessed 19 December 2023.

Al Halbusi, H., Williams, K. A., Ramayah, T., Aldieri, L., & Vinci, C. P. (2021). Linking ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees’ ethical behavior: The moderating role of person–organization fit. Personnel Review, 50(1), 159–118.

Alsop, R. J. (2006). Business ethics education in business schools: A commentary. Journal of Management Education, 30(1), 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562905280834

Ardaugh, D. (2007). The ethical basis for HRM professionalism and codes of conduct. In A. H. Pilkington, R. A. Macklin, & T. Campbell (Eds.), Human Resource. Management: Ethics and employment (pp. 152–170). Oxford University Press.

Ardaugh, D. (2010). Business as a profession: A bridge too far or fair way to go? Lambert Academic Publishing.

Armstrong, M. (2022). Armstrong’s handbook of performance management: An evidenced based guide to Performance Leadership. Kogan Page.

Asgary, N., & Li, G. (2016). Corporate social responsibility: Its economic impact and link to the bullwhip effect. Journal of Business Ethics, 135, 665–681.

Bailey, C., Mankin, D., Kellihe, C., & Garavan, T. (2018). Strategic Human Resource Management. Oxford.

Barker, R. (2010). No, Management is not a profession (pp. 52–60). Harvard Business Review.

Bassot, B. (2022). Doing qualitative desk-based research: A practical guide to writing an excellent dissertation. Policy Press.

Bice, S. (2017). Corporate social responsibility as institution: A social mechanisms framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 143, 17–34.

Blaikie, N. (2007). Approaches to social enquiry: Advancing knowledge (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

Bolman, L. E., & Deal, T. (2021). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership (7th ed.). Wiley & Sons.

Bowman, J., & Menzel, D. (Eds.). (1998). Teaching ethics and values in public administration programs: Innovations, strategies, and issues. State University of New York Press.

Boyatzis, R. E. (1982). The competent manager: A model for effective performance. Wiley & Sons.

Bravo, R., Matute, J., & Pina, J. M. (2012). Corporate social responsibility as a vehicle to reveal the corporate identity: A study focused on the websites of Spanish financial entities. Journal of Business Ethics, 107, 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1027-2

Brown, P., Power, S. T., & G & Allouch, A. (2016). Credentials, talent and cultural capital: A comparative study of educational elites in England and France. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37(2), 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.920247

Buckley, M. R., Beu, D. S., Frink, D. D., Howard, J. L., Berkson, H., Mobbs, T. A., & Ferris, G. R. (2001). Ethical issues in human resources systems. Human Resource Management Review, 11(1-2), 11–29.

Canós-Darós, L., Peris-Ortiz, M. and Rueda-Armengot, C. (2008). A fuzzy tool for classifying jobs in the company, 2nd International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Industrial Management, XII Congreso de Ingenieria de Organizacion, Burgos, September 3–5.

Chadwick, R., & Thompson, A. (2000). Professional ethics and labour disputes: Medicine and nursing in the United Kingdom. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 9(4), 483–497.

Charlo, M. J., Moya, I., & Muñoz, A. M. (2017). Sustainable development in Spanish listed companies: A strategic approach. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 24(3), 222–223.

Cheetham, G., & Chivers, G. (2001). How professionals learn in practice: An investigation of informal learning amongst people working in professions. Journal of European Industrial Training, 25(5), 247–292.

Cohen, E., & King, D. (2017). Human resource management: Developing sustainability mindsets. In P. Molthan-Hill (Ed.), The Business Student’s Guide to Sustainable Management, Chapter 9. Routledge.

Cohen, J., Ding, Y., Lesage, C., & Stolowy, H. (2010). Corporate fraud and managers’ behavior: Evidence from the press. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(2), 271–315.

Collins, D. (2009). Essentials of business ethics: Creating an organization Sydney: of Integrity and Superior Performance. Wiley, and Sons.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design. Sage Publications.

Csillag, S. (2019). Ethical dilemmas and moral muteness in the HRM profession. Society and Economy, 41(1), 125–144.

Curnow, C. K., & McGonigle, T. P. (2006). The effects of government initiatives on the professionalization of occupations. Human Resource Management Review, 16(3), 284–293.

Daft, R. L. (2021). Organization theory & design. Cengage learning.

de Gama, N., McKenna, S., & Peticca-Harris, A. (2012). Ethics and HRM: Theoretical and conceptual analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 1(11), 97–108.

Dean, K. L., Beggs, J. M., & Fomaciari, C. J. (2007). Teaching ethics and accreditation. Journal of Business Ethics Education, 4, 5–25. https://doi.org/10.5840/jbee200742

DeConinck, J. B. (2011). The effects of ethical climate on organizational identification, supervisory trust, and turnover among salespeople. Journal of Business Research, 64(6), 617–624.

Dellaportas, S., Gibson, K., Alagiah, R., Hutchinson, M., Leung, P., & Van Homrigh, D. (2005). Ethics, governance and accountability: A professional perspective. Wiley.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2018). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Dessler, G. (2015). Human resource management (14th ed.). Pearson.

Donker, H., Poff, D., & Zahir, S. (2008). Corporate values, codes of ethics, and firm performance: A look at the Canadian context. Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9579-x

Driscoll, D. N., & Hoffman, W. M. (2000). Ethics matters: How to implement values-driven management. Bentley College Center for Business Ethics.

DuBrin, A. (2022). Fundamentals of human resource management. Academic Media Solutions.

ECI. (2022). Ethics and compliance institute, at https://www.ethics.org/ accessed 12 January 2024.

Ehnert, I., Parsa, S., Roper, I., Wagner, M., & Muller-Camen, M. (2015). Reporting on sustainability and HRM: A comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world's largest companies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27, 1–21.

Eraut, M. R. (2000). Non formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(1), 113–136.

Ferrary, M. A. (2009). Stakeholder’s perspective on human resource management. Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9868-z

Ferrell, O. C., Fraedrich, J., & Ferrell, L. (2021). Business ethics: Ethical decision making and cases. Houghton Mifflin.

Flexner, A. (1910). Medical education in the United States and Canada: A report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Stanford.

Forte, A. (2004). Antecedents of managers moral reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 51(4), 313–347.

Freidson, E. (1970). The profession of medicine: A study of the sociology of applied knowledge. Harper & Row.

Fu, R., Tang, Y., & Chen, G. (2020). Chief sustainability officers and corporate social (Ir)-responsibility. Strategic Management Journal, 41(4), 656–680.

Gold, J., Rodgers, H., & Smith, V. (2002). The future of the professions: Are they up for it? Foresight, 4(2), 46–53.

Greenberg, J. (1987). Taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Academy of Management Review, 12(1), 9–22.

Greenwood, M. (2013). Ethical analyses of HRM: A review and research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics, 114, 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1354-y

Hamel, G. (2012). What matters now: How to win in a world of relentless change, ferocious competition and unstoppable innovation. Jossey-Bass.

Hellriegel, D., Jackson, S. E., & Slocum, J. W. (2008). Managing: A competency based approach (11th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Henry, G. T. (1990). Practical sampling. In Applied Social Research Methods Series 21. Sage Publications.

Hetmański, M. (2018). Expert knowledge: Its structure, functions and limits. Studia Humana, 7(3), 11–20.

Hoffman, W. M., Driscoll, D., & Painter-Morland, M. (2001). Integrating ethics. In C. Moon & C. Bonny (Eds.), Business ethics: Facing up to the issues (pp. 38–54). The Economist Books.