Abstract

This study was designed to investigate the factors affecting ethical practices of public relations professionals in public relations firms. In particular, the following organizational ethics factors were examined: (1) presence of ethics code, (2) top management support for ethical practice, (3) ethical climate, and (4) perception of the association between career success and ethical practice. Analysis revealed that the presence of an ethics code along with top management support and a non-egoistic ethical climate within public relations firms significantly influenced public relations professionals' ethical practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Given the ethical turbulence of public relations practices, ethics has recently been a key issue of consideration among scholars as well as practitioners (Edelman 1992; Huang 2001; Kim 2003; Tilley 2005). Bowen (2004) claimed that “public relations is a field fraught with ethical dilemmas” (p. 65). This statement reflects the fact that unethical public relations practices have been gradually tarnishing the image, reputation, and professionalism of the field. Thus far, the field has primarily turned to ethics codes of associations in its efforts to curb such unethical practices (Bowen 2007).

Recently, a few scholars have jumped into the ring to fight the battle against unethical practices by employing a new perspective. They have claimed that individual public relations firms' ethics codes may represent a more effective mechanism for fighting unethical practices than associations' ethics codes, and they cite a couple of specific reasons. First, an individual firm's code of ethics can be enforced among its employees, public relations practitioners (Ki and Kim 2010). Second, a firm's code communicates the core ethical values that firm promises to adhere to in its practices.

Claiming the advantages of individual firm codes, Ki and Kim (2010) investigated the current status of ethics codes in public relations firms in the USA and discovered that about 60% of the firms possessed ethics codes. Following the aforementioned study, Ki, Choi and Lee (2011) empirically examined the effectiveness of ethics code in public relations firms and discovered that public relations practitioners working in firms with ethics codes tended to display more negative attitudes towards unethical public relations practices than their counterparts at firms without ethics codes.

While the establishment of ethics codes by individual public relations firms represents a good start, these codes cannot be fully effective by themselves. Instead, to increase efficacy, public relations firms should reinforce their ethics codes through organizational ethics factors, such as top management support, ethical climate, and the association between ethical behavior and career success in the organization. While some evidence exists on a relationship between organizational ethics factors and ethical decision-making behavior of employees in ethics literature, no previous studies have empirically applied this relationship to public relations firms.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to empirically investigate the determinants of ethical practices of public relations practitioners within public relations firms. In particular, this study focuses on four specific organizational ethics factors—the existence of an ethics code, a favorable ethical climate, top management support for ethical practices, and a strong association between ethical practice and career success in the firm. These factors are assessed in terms of their influence on ethical practices of public relations professionals and the extent to which they successfully promote ethical behavior.

The outcome of this study will contribute to both scholarship and practice within the public relations field. Investigating the determinants of ethical practice of public relations is important as it increases scholars' and practitioners' understanding of the factors associated with ethical public relations practices. Additionally, considering the consequences of ethics in public relations practices is a fruitful avenue for continued public relations ethics research.

Background and theoretical framework

Efficacy of ethics codes

Scholars have continually added to the empirical evidence supporting the efficacy of ethics codes in discouraging unethical practices (Bennett 1988; Ferrell and Skinner 1988; Hegarty and Sims 1979; McCabe et al. 1996; Pierce and Henry 1996; Purcell 1975; Singhapakdi and Vitell 1990; Weaver and Ferrell 1977; White and Montgomery 1980). Moreover, scholars have claimed several direct and indirect benefits of ethics codes for companies, such as: (1) improvement of the company's bottom line (Leeper 1996; Werner 1992), (2) protection during litigation or regulatory actions (White and Montgomery 1980), (3) promotion of corporate social responsibility, positive employee behavior, management, and corporate culture (Robin et al. 1989), and (4) creation of a positive impression of a firm among its stakeholders (Berenbein 1988; Brooks 1989; Cressey and Moore 1983).

Since the mere existence of ethics codes in firms may correspond with only a limited impact on ethical practices, scholars conducting ethics studies have made an attempt to pinpoint the determinants of the codes' efficacy. In a meta-analytic review of key efficacy factors of ethics codes in ethics literature, Ford and Richardson (1994) broadly divided the determinants into two groups—individual factors and situational factors (e.g., peer group influence, top management influence, organization size, and industry type). Individual factors include variables that are a result of birth (e.g., age, sex, nationality, etc.) and those that are outcomes of the human development and socialization process (e.g., personality, attitudes, values, education, religion, employment, etc.). These variables embody the sum of one's life experiences and circumstances of birth that an individual brings to the ethical decision-making process (Ford and Richardson 1994). As these individual factors are predetermined and cannot be controlled by public relations firms, this study focuses primarily on situational factors. In particular, this study assesses three organizational ethics factors—ethical climate, top management support for ethical behavior, and the association between career success in the organization and ethical practices—in addition to the existence of an ethics code.

Organizational ethics factors

In ethics studies, organizationalFootnote 1 culture has gained attention as a primary influential factor of ethical behavior. To emphasize the importance of organizational culture, Cassel et al. (1997) claimed, “design and implementation of a code of ethics does not take place in a social vacuum. Therefore it is important to realize that certain contextual phenomena will have a bearing upon how people respond to any code of ethics” (p. 1,080). Organizational culture is the common set of assumptions, beliefs, and values that develops within an organization to cope with the external and internal environment and that is passed on to new members to guide their actions with respect to these environments (Schein 1984).

The presence of ethics codes in public relations firms represents one way of communicating ethical standards to public relations professionals in those firms. As such, favorable organizational factors, such as top management support for ethical behavior, a favorable ethical climate, and a strong association between ethical practice and career success in the public relations firms, can boost the impact of ethics codes on public relations professionals' behavior. For ease of reference, these factors are termed organizational ethics variables.

Ethical climate

Since Victor and Cullen (1987, 1988) introduced the concept of ethical climate to predict ethical conduct in organizations, and it has served as a key conceptual foundation in ethics studies (Martin and Cullen 2006). Ethical climate is defined as “the shared perception of how ethical issues should be addressed and what ethically correct behavior is” (Deshpande 1996, p. 655). Adopting the aforementioned definition, this study conceptualizes ethical climate as “the shared perceptions among public relations practitioners in a firm of the nature of ethically correct practice and how ethical issues should be handled within the firm.”

An organization's ethical climate can result in four main outcomes for the employees—organizational commitment, job satisfaction, psychological well-being, and preventing unethical behavior. For example, several studies have confirmed that a favorable ethical climate positively influences employee job satisfaction, potential promotion, and supervisors (e.g., Deshpande 1996; Okpara 2004). More importantly, findings from multiple studies emphasized the importance of a firm's ethical climate as a leading factor in influencing ethical behavior (Deshpande 1996; Deshpande et al. 2000; Fritzsche 1991; Wimbush and Shepard 1994) and preventing dysfunctional behaviors among employees within the firm (Barnett and Vaicys 2000; Elm and Nichols 1993; Martin and Cullen 2006.

It has been suggested that there are multiple dimensions of ethical climate, and these different dimensions tend to convey varied indications to employees regarding what is acceptable behavior (Cullen et al. 1989; Wimbush and Shepard 1994). While there is some variation among the underlying dimensions of ethical climate, the three dimensions—egoism, principle, and benevolence—as framed by Victor and Cullen (1987), are most commonly accepted (Fritzsche 1991). Egoism is the application of behavior for maximizing self-interest. Principle is the same concept of deontology, which is the application of universal standards, rules, codes, and procedures to behavior. Benevolence is similar to the concept of utilitarianism in classical ethical theories. This construct entails behavior that maximizes the well-being of as many people as possible. The measure of three typologies of ethical climate has been applied to various disciplines, including education (e.g., Rosenblatt and Peled 2002) and management (e.g., Neubaum et al. 2004; Weaver 1995).

Studies assessing how ethical climate affects ethical decision making in firms have proliferated in business and organizational literature (e.g., Barnett and Vaicys 2000; Deshpande 1996; Deshpande et al. 2000; Elm and Nichols 1993; Fritzsche 1991; Martin and Cullen 2006; Wimbush and Shepard 1994). However, to the researchers' knowledge, none of the studies in the public relations field have specifically examined whether the ethical climate within public relations firms affects public relations professionals' ethical decision making in their practices. Since the ethical climate in a firm tends to shape the firm's collective norms for ethical behavior (Trevino 1986), this research suggests in accordance with organizational ethics studies that ethical climate may also play an important role in influencing ethical behavior of practitioners in public relations firms (e.g., Sinclair 1993).

Top management support for ethical behavior

Top management support for ethical practice has been found to be another key ingredient in encouraging employees' ethical behavior. Hunt et al. (1984) originally developed a measure of “top management support for ethical practices” and summarized the following three actions that top management can take to ameliorate employees' ethical dilemmas: (1) serve as role models by performing their own practices faultlessly, (2) promote ethical practices by promptly reprimanding unethical conduct, and (3) develop and promote ethics codes of both their company and the industry. Hunt et al. (1984) determined that top management action is the single best predictor of ethical problems of marketing researchers. Trevino et al. (1999) noted that although a firm's ethics code rarely influenced practitioners' ethical behavior, a value-based cultural approach—leaders' commitment to ethical behavior, rewards for ethical practice, and congruency between policies and actions—positively influenced ethical behavior among employees. Consequently, a firm's ethics code can be more effective when firm management and the board of directors support it (Raiborn and Payne 1990). Moreover, top management has been found to positively influence other important outcomes within organizations, such as organizational performance, productivity, success, and job satisfaction (Boo and Koh 2001; Vitell and Davis 1990). In general, top management support is influential for the overall effectiveness of an organization.

In public relations, top management support has been discussed as a key factor in influencing public relations practices (e.g., Dozier 1992; Grunig and Grunig 1989; Lauzen 1992a, b; Ryan and Martinson 1984; Schneider 1985). Top managers represent an essential link between ethics codes and practitioners' ethical practices. If managers fail to discuss the importance of ethical practices with their employees, these practitioners will likely believe that ethical behavior is not significant or necessary. Thus far, none of the studies in this area have empirically tested the effect of top management support on ethical practices in public relations firms. This study considers top management support in the following way: “top management in public relations firms understands the importance of ethical practice among employee practitioners and is dedicated to developing more ethically oriented work settings.”

The association between ethical behavior and career success

Luthans and Stajkovic (1999) demonstrated that a person's behavior tends to be encouraged by three types of reinforcers—feedback, money, and social recognition. Several empirical studies tested this variable in terms of job satisfaction and confirmed that employees demonstrate higher levels of satisfaction when they can perceive a clear relationship between ethical behavior and career success (Vitell and Davis 1990).

Compared to the other two variables, “the association between ethical behavior and career success” has rarely been tested in terms of ethical decision making with the exception of one study. Boo and Koh (2001) investigated if employees' perceptions of the positive association between ethical behavior and career success encourage more ethical practices. They added empirical evidence confirming that employees tended to behave more ethically when they perceived a positive relationship between ethical behavior and career success. Based on the empirical evidence, it is assumed that in a public relations firm where ethical practice is closely tied with career success, ethical practice of public relations practitioners would be reinforced. On the other hand, when public relations professionals believe unethical practices are necessary for success in their careers, such perceptions would motivate unethical practice.

This study aims to evaluate the following four variables that could contribute to more ethical public relations practices: whether public relations firms explicitly develop a code of ethics for guiding public relations professionals, whether public relations professionals perceive a favorable ethical climate within their firms, whether strong top management support for ethical practices exists within firms, and whether there is a clear association between ethical practices and career success in public relations firms. Figure 1 represents the proposed research framework for this study.

Based on the exploratory nature of this study, the following research question was proposed:

Research question: To what extent do the organizational ethics factors affect the ethical practices of public relations professionals in public relations firms?

Methodology

Population and samples

The present study focuses on the factors affecting ethical practices of public relations professionals in public relations firms. In this study, practitioners working at public relations firms in Korea were selected for the survey. In-house practitioners were excluded because corporations are likely to possess ethical standards that generally apply to all employees rather than providing public relations specific guidelines.

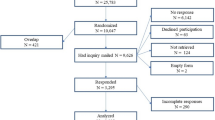

There was no complete directory of Korean public relations practitioners available at the time this study was conducted. Therefore, this study used the list of public relations firms cited by the Korea Public Relations Consultancy Association, which included 31 firms. CEOs of the firms on the list were contacted to request their cooperation for this research. The researchers contacted the CEOs via emails or phone calls to provide them with information regarding the purposes of the study and a brief description of the procedure that would be employed. Among the 31 CEOs contacted, 19 indicated their intention to encourage their employees to participate in the survey. Public relations professionals from the firms where the CEOs encouraged participation were chosen for the survey. While all public relations professionals at these firms received the questionnaire, participation was completely voluntary.

The only necessary qualification for participation in this study was employment in the selected public relations firms at the time the survey was conducted. Public relations professionals holding various positions and demonstrating different levels of professional experience provided meaningful perspectives for the current research.

Research procedure

To answer the research question, this study conducted a survey with public relations professionals in public relations firms in Korea. The survey including two preliminary tests, were performed in Korea between September and October 2008.

Two pretests and questionnaire development

Two pilot tests were conducted to improve the quality of the questionnaire for the main survey. In the first test, eight senior level public relations professionals, all of whom possessed a minimum of 5 years professional experience and held a position higher than general manager, were invited to comment on the original questionnaire. The questionnaire was then revised based on their feedback. Another 30 public relations professionals participated in the second pretest to assess the clarity and face validity of the revised questionnaire.

Main survey and data collection

The method of personal delivery and collection of a self-administered questionnaire was used to increase the survey response rate. Lovelock et al. (1976) suggested that personal delivery of surveys by trained researchers appears to yield higher response rates than mail surveys at competitive costs.

The researchers visited CEOs and asked them to distribute questionnaires to their employees. Three days after their initial visits, the researchers followed up to collect the questionnaires from the CEOs. Of the 470 questionnaires distributed, 249 were completed. The response rate was 53%. Thirty questionnaires that showed response set were excluded. For data analysis, this study used listwise deletion yielding a final sample of 203.

Measures

Dependent variables

The dependent variable, public relations practitioners' ethical behavior, was measured using four ethically suspicious vignettes that are intended to ascertain the respondents' “likely behavior.” This study adapted the four ethical dilemma scenarios developed by Pratt et al. (1994), translated and reproduced as shown in Appendix 1. The four scenarios present ethical dilemmas involving “disguising information” and “conflict of interest.” The professionals were asked to indicate their likelihood of performing a particular action on a scale ranging from “1” (definitely yes) to “4” (definitely no). A higher score corresponds with a higher level of ethical practice.

Independent variables

This study is comprised of four independent variables, which are referred to as organizational ethics factors—the presence of an ethics code, top management support for ethical practice, ethical climate, and the association between career success and ethical practices. These factors were measured as follows (See Appendix 2 for the measurement items):

Existence of ethics code

The existence of a public relations firm's code of ethics was measured directly as a dichotomous-response (i.e., “yes” or “no”) question. In the analysis, this variable was treated as a dummy variable (yes = 1, no = 0).

Top management support for ethical behavior

The three items developed by Hunt et al. (1984) to measure top management action were adapted for the present study. An additional item was added to provide a four-item measure. A 9-point scale, with “1” representing “strongly disagree” and “9” representing “strongly agree,” was used. A high mean score represents strong top management support for ethical behavior.

Ethical climate

To measure ethical climate in public relations firms, the ethical climate questionnaire developed by Cullen et al. (1993) was adapted. The following three dimensions of ethical climate were assessed: (1) egoistic, which highlights firms' profits; (2) benevolent, which emphasizes team interest; and (3) principled, which focuses on roles and standard operating procedures. Additional items were added so that each of the three categories was measured by four items on a 9-point scale. Similar to the other variable, “1” represents “strongly disagree” and “9” represents “strongly agree.”

The association between ethical behavior and career success

To measure the perception of the association between ethical behavior and career success in public relations firms, the 7-item scale developed by Hunt et al. (1984) was used with an additional item added to provide a 7-item instrument. Each item was measured on a 9-point scale (where “1” = “strongly disagree” and “9” = “strongly agree”). A high mean score indicates a strong association between ethical behavior and career success in public relations firms.

Reliabilities of the measures

Measurement items for each variable were deleted if they (1) were extracted as the second factor of the intended factor, (2) included opposite signs of factor loading coefficients among the other items in the intended factors, and (3) had factor loading values of less than .65 with the other items of their respective subscales based on the suggestion (Hair et al. 1998). Cronbach's alphas for the variables were as follows: ethical practices (four items) = .85, top management support (three items) = .80, egoism (two items) = .69, principle (three items) = .73, benevolence (three items) = .88, and the association between career success and ethical behavior (four items) = .94. With the exception of the variable egoism, all variables satisfy the acceptable minimal reliability score of α = .70 for a scale to demonstrate good internal consistency (Nunnally 1978; Hair et al. 1998). Nevertheless, the reliability of the measurement items for egoism is very close to the acceptable limit and is kept for subsequent analysis.

Demographic profiles

The questionnaire concluded with several demographic questions. Items solicited information regarding respondents' gender, age, years of public relations experience, and rank of current position. Of the 202 participants, female respondents made up the majority (n = 150, 74% female, vs. n = 52, 26% male). These statistics suggest that the gender of the sample was reasonably reflective of the overall public relations professional population in Korea. The mean age of the participants was 31 (SD = 5.73) with a range from 23 to 56. More than 80% of the respondents reported having had less than 5 years' experience in public relations, with the sample average having 1.8 years of experience in the field. The education levels of the participants were as follows: high school diploma (n = 4, 2.3%), college degree (n = 137, 78.7%), and a graduate degree (n = 33, 19%). Approximately 40% responded that they worked in either upper-middle management or top management.

Statistical procedures for data analysis

To answer the research question, multiple regression analysis was used. Multiple regression analysis is useful for identifying which of the organizational ethics factors—the presence of an ethics code, top management support, egoism, benevolence, principle, the association between career success and ethical practice—are significantly associated with ethical public relations practices.

Results

Correlation analysis

This study used composite variables, which are useful for enhancing the parsimony and ease of convergence for the proposed model. The composite scores obtained from principal component analysis for each of the six variables were employed for correlation analysis. A correlation analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between independent and dependent variables. Table 1 presents the results of the correlation analysis. Overall, top management support for ethical practices, benevolence of the ethical climate, and code existence were positively associated with ethical practice while egoism was negatively associated with ethical practice.

Multiple regression analysis

Due to the correlation among variables, stepwise regression analysis was conducted. The research question asked to what extent the organizational ethics factors affect the ethical practices of public relations professionals in public relations firms. With reference to the relative influence of the organizational ethics factors on ethical practices of public relations professionals, ethical practices were regressed on the organizational ethics factors using stepwise regression analysis. The organizational ethics factors are independent variables, while ethical practice is the dependent variable for the regression analysis.

As shown in Table 2, the analysis revealed several findings. The stepwise regression analysis produced significant results. First, the existence of an ethics code within a public relations firm was the primary predictor of ethical practice of the public relations professionals in that firm. Second, an egoistic ethical climate in a public relations firm negatively influenced the ethical practices of the firm's public relations practitioners. Third, top management support for ethical practices is a significant predictor of ethical practice among public relations professionals in their firms. The amount of explained variance was 15%.

Discussion and conclusion

This study was designed to investigate what organizational ethics factors in public relations firms can more effectively influence practitioners' ethical practice in the firms. Among the tested organizational ethics variables, the presence of an ethics code, top management support for ethical practices, and a non-egoistic ethical climate significantly influenced the ethical practices of public relations professionals in the firms (see Fig. 2). Of these significant variables, the presence of an ethics code in a public relations firm had the strongest impact on the ethical practices of the public relations professionals in that firm. In particular, the findings indicate that practitioners working in public relations firms with ethics codes are more likely to demonstrate higher ethical standards than their counterparts who practice at firms without codes. Regression analysis indicated that the ethical practice of public relations professionals is influenced by firms' ethics variables, particularly top management support for ethical practice, which has a positive influence, as well as egoism in the ethical climate, which negative influences practitioners' ethical behavior, though the effect size is moderate. These findings support previous studies assessing the impact of organizational ethics variables on the ethical behavior of employees (see, for example, Bowman 1981; Ford and Richardson 1994). The favorable association between public relations firms' ethics and practitioners' ethical practice has important implications and suggests further questions for future scholarship within the field.

This study found that the presence of ethics codes within public relations firms tends to encourage practitioners to apply the codes to their own practices. Like other studies that have confirmed the effects of ethics code on ethical practices (e.g., Bennett 1988; Ferrell and Skinner 1988; Hegarty and Sims 1979; McCabe et al. 1996; Pierce and Henry 1996; Purcell 1975; Singhapakdi and Vitell 1990; Weaver and Ferrell 1977; White and Montgomery 1980), this study added additional empirical evidence supporting the efficacy of ethics codes in discouraging unethical practices. Given the obvious evidence indicating the benefits of establishing ethics codes, more public relations firms should develop codes of ethics to guide their practitioners' ethical practices.

This study found that when top management in public relations firms was perceived as strongly supporting ethical practices, public relations professionals were much more likely to practice ethically themselves, which is a trend supported by other ethics studies (Hunt et al. 1984; Raiborn and Payne 1990; Trevino et al. 1999). This finding implies that top management support for ethical practices in public relations makes a difference. When top management expresses that unethical practice will not be tolerated, public relations professionals exhibit less ethically problematic behavior. If members of top management plan to reprimand practitioners for unethical behavior, they have an obligation to firm employees to clearly state the guidelines for acceptable and unacceptable behavior. Therefore, though public relations firms' ethics codes are useful starting points for discouraging unethical practice among public relations professionals, top management in these firms can significantly boost the ethical practices of their employees by taking a positive stance against unethical behavior and rewarding ethical practices.

To emphasize the importance of ethical practice among professionals in public relations firms, top management must effectively communicate their firms' ethical values to their employees. Public relations firms should establish a workshop program for top managers that could offer advice regarding ethical dilemmas, convey expectations, and provide tips for solving ethical problems. As indicated by Stevens (1999), training programs are the best method for conveying ethical expectations. In addition, top managers need to develop dialogs with their teams about ethics, so that they can explore situations unique to each work team. Public relations firms could improve the efficacy of ethical standards by establishing communication programs such as web-based learning sessions, a web site, and easily employed meeting tools and techniques that allow top managers and their teams to communicate about ethical issues in public relations.

This study found that an egoistic ethical climate within a public relations firm negatively affects employees' ethical practices within the firms. This finding confirms Wimbush and Shepard's (1994) study, which found that high egoism within an organization's ethical climate tends to be associated with unethical behavior among its employees. The current study's findings imply that when professionals perceive that their firms emphasize self-interest and profits, they are then apt to lower their own ethical standards and practice unethically. This finding may derive from the characteristics and role of public relations practices, which are far from egoistic. When practicing public relations, professionals need to consider not only their firms and clients but also other strategic publics. In addition, public relations professionals should not simply serve the client, but should also inform necessary diverse publics. A public relations firm demonstrating high egoism climate might be successful in the short term. However, such a firm would likely lose professionals with high ethical standards who were not satisfied with their jobs due to conflicts between the firm's code of ethics and their own. Consequently, these kinds of firms would not likely be successful in the long term.

Although the analysis identified several significant variables, some of the variables tested were found not to be significant factors of ethical practices. For example, benevolent and principled ethical climates as well as perceptions of the association between career success and ethical behavior had no significant effects on the ethical practices of public relations practitioners. These results are somewhat surprising, especially for the benevolent and principled ethical climate variables, given the significance placed on these variables in ethics literature in terms of influence on ethical practices (e.g., VanSandt et al. 2006; Victor and Cullen 1988).

Since the findings related to benevolence and principled ethical climate seem counterintuitive, measurement problems may have been a factor. Perhaps the items measuring benevolence and principled ethical climate do not accurately reflect the ethical climate of public relations firms because these measures were originally developed in the business field and had never previously been applied to a public relations context. This may be true for “principled ethical climate” measures. Originally, four items were used to tap a principled ethical climate. However, during the factor analysis, only two items were successfully loaded into a factor. The other two items had a low factor score and the opposite sign of the coefficient. Therefore, it would be necessary for future research to include additional measurement items to more appropriately evaluate ethical climate in a public relations environment.

Another explanation for the insignificant effect of ethical climate could be due to the indirect relationship between the two ethical climates and ethical practices. Public relations professionals' perceptions of the ethical climate in their firms may not directly influence their ethical practices. That is, efforts to change public relations professionals' perceptions of the ethical climate may not result in dramatic shifts in their ethical decision making. Perceptions of these ethical climates may instead have a more indirect effect on professionals' ethical practice.

This study did not find that the perception of the association between career success and ethical practice in the firm had a significant influence on practitioners' ethical behavior. This lack of relationship may be due to the nature of public relations practices and the size of public relations firms. Public relations firms are likely to be smaller and have fewer hierarchical levels than corporations. Thus, specific unethical practices are less likely to lead to success in less bureaucratically oriented agencies. Another possible explanation for this insignificant relationship may be that practitioners perceived the ethical dilemma scenarios presented in this study to be only moderately unethical. That is, when professionals responded to the first and third scenarios, they may have perceived more serious breaches of ethics than the types of unethical practices specifically identified in the second and the last scenarios. Thus, if the unethical practices described in the scenarios had spanned a wider range of severity, the results might have been different. Finally, the insignificant findings could be a result of the way the questions were constructed and translated. For example, one measurement item—“in order to succeed in my firm, it is often not necessary to compromise one's ethics”—has the qualifier “often,” and the remaining items do not have such qualifiers. Participants may have interpreted the items differently based on the existence of a qualifier.

Limitation and future research agenda

Like other studies, this study has several limitations that can be translated into fertile opportunities for future research. First, this study excluded in-house public relations professionals because it specifically focused on the ethical practices of professionals working at public relations firms. In future research, it could be meaningful to compare the similarities or differences between professionals in public relations firms and those practicing at in-house public relations departments. Second, this study surveyed public relations professionals in Korea. One country's professionals do not necessarily represent the perspectives of public relations practitioners worldwide. Therefore, the findings of this study should be interpreted with this limitation in mind. Third, this study did not consider the demographic variables as an influential factor as this study is more interested in organizational factors as influential factor of ethical practices. Future studies may want to consider testing the predictive influences of demographic variables such as gender, age, level of education, level of employment, etc. to ethical practices in public relations. These variables may provide more insights into the ethical practices between different public relations personnel in public relations firms. Additionally, future research should consider the application of this study's framework to other countries so that more generalizable findings can be obtained.

Documenting the linkages among organizational ethics factors and ethical practices of public relations professionals has important implications. The authors believe that this study offers important, though tentative, insight into understanding factors that influence ethical practices, and they hope that these findings will help the public relations field move another step forward in its promotion of ethical practice among its practitioners.

Notes

Here “organization” refers to public relations firms. As this study focuses on public relations firms' ethics, in-house public relations departments were excluded from the study.

References

Barnett, T., & Vaicys, C. (2000). The moderating effect of individuals' perceptions of ethical work climate on ethical judgments and behavioral intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(4), 351–362.

Bennett, A. (1988). Ethics codes spread despite skepticism. Wall Street Journal, p. 15.

Berenbein, R. E. (1988). Ethics codes and educational programs. Security, October, 91–97.

Boo, E. H. Y., & Koh, H. C. (2001). The influence of organizational and code-supporting variables on the effectiveness of a code of ethics. Teaching Business Ethics, 5, 357–373.

Brooks, L. J. (1989). Corporate codes of ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 8 (February/March), 117–129.

Bowen, S. A. (2004). Expansion of ethics as the tenth generic principle of public relations excellence: a Kantian theory and model for managing ethical issues. Journal of Public Relations Research, 16, 65–92.

Bowen, S. A. (2007). Ethics and public relations. Gainesville: Institute for Public Relations.

Bowman, J. (1981). The management of ethics: codes of conduct in organizations. Public Personnel Management Journal, 10, 59–64.

Cassel, C., Johnson, P., & Smith, K. (1997). Opening the black box: corporate codes of ethics in their organizational context. Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 1077–1093.

Cressey, D., & Moore, C. (1983). Managerial values and corporate codes of ethics. California Management Review, 25, 53–77.

Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Stephens, C. (1989). An ethical weather report: assessing the organization's ethical climate. Organizational Dynamics, 50–62.

Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Bronson, W. J. (1993). The ethical climate questionnaire: an assessment of its development and validity. Psychological Reports, 73, 667–674.

Deshpande, S. P. (1996). The impact of ethical climate types on facets of job satisfaction: an empirical investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 15, 655–660.

Deshpande, S. P., George, E., & Joseph, J. (2000). Ethical Climates and Managerial Success in Russian Organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 23(2), 211–217.

Dozier, D. M. (1992). The organizational roles of communications and public relations practitioners. In J. E. Grunig (Ed.), Excellence in public relations and communication management (pp. 327–356). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Edelman, D. J. (1992). Ethical behavior is key to field's future. The Public Relations Journal, 48(11), 32.

Elm, D. R., & Nichols, M. L. (1993). An investigation of the moral reasoning of managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 12(11), 817–833.

Ferrell, O. C. & Skinner, S. J. (1988). Ethical behavior and bureaucratic structure in marketing research organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 25 (February), 103–109

Ford, R. C., & Richardson, W. D. (1994). Ethical decision making: a review of the empirical literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 205–221.

Fritzsche, D. J. (1991). A model of decision-making incorporating ethical values. Journal of Business Ethics, 2, 291–299.

Grunig, J. E., & Grunig, L. A. (1989). Toward a theory of the public relations behavior of organizations: review of a program of research. In J. E. Grunig & L. A. Grunig (Eds.), Public relations research annual (Vol. 1, pp. 27–63). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Hegarty, W. H., & Sims, H. P. (1979). Organizational philosophy, politics, and objectives related to unethical decision behavior: A laboratory experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(3), 331–338.

Huang, Y.-H. (2001). Should a public relations code of ethics be enforced? Journal of Business Ethics, 31, 259–270.

Hunt, S. D., Chonko, L. B., & Wilcox, J. B. (1984). Ethical problems of marketing researchers. Journal of Marketing Research, 21(August), 309–324.

Ki, E.-J., & Kim, S.-Y. (2010). Ethics statements of public relations firms: what do they say? Journal of Business Ethics, 91, 223–236.

Ki, E.-J., Choi, H. L., Lee, J. (2011). Does ethics statement of a public relations firm make a difference? Yes it does!! Journal of Business Ethics, pp. 1–10. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-0971-1.

Kim, Y. (2003). Ethical standards and ideology among Korean public relations practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 42, 209–223.

Lauzen, M. M. (1992a). Public relations roles, intraorganizational power, and encroachment. Journal of Public Relations Research, 4, 61–80.

Lauzen, M. M. (1992b). Supervisor versus practitioner perceptions: when expectations and reality meet. Management Communication Quarterly, 85–102.

Leeper, K. A. (1996). Public relations ethics and communitarianism: A preliminary investigation. Public Relations Review, 22, 163–179.

Lovelock, C. H., Stiff, R., Cullwick, D., & Kaufman, I. M. (1976). An evaluation of the effectiveness of drop-off questionnaire delivery. Journal of Marketing Research, 13(4), 358–364.

Luthans, F., & Stajkovic, A. D. (1999). Reinforce for Performance: The Need to Go beyond Pay and Even Rewards. The Academy of Management Executive, 13(2), 49–57

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (1996). The influence of collegiate and corporate codes of conduct on ethics-related behavior in the workplace. Business Ethics Quarterly, 6(4), 461–476.

Martin, K. D., & Cullen, J. B. (2006). Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(2), 175–194.

Neubaum, D. O., Mitchell, M. S., & Schminke, M. (2004). Firm newness, entrepreneurial orientation, and ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(4), 335–347.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Okpara, J. O. (2004). Personal characteristics as predictors of job satisfaction: an exploratory study of IT managers in a developing country. Information Technology and People, 17(3), 327–338.

Pierce, M. A., & Henry, J. W. (1996). Computer ethics: The role of personal, informal, and formal codes. Journal of Business Ethics, 15, 425–437.

Purcell, T. V. (1975). A practical guide to ethics in business. Business & Society Review, 13(Spring), 43–50.

Pratt, C. B., Im, S., & Montague, S. N. (1994). Investigating the application of deontology among U.S. public relations practitioners. Journal of Public Relations Research, 6(4), 241–266.

Raiborn, C. A., & Payne, D. (1990). Corporate codes of conduct: a collective conscience and continuum. Journal of Business Ethics, 9, 879–889.

Robin, D., Giallourakis, M., David, F., & Moritz, T. (1989). A different look at codes of ethics. Business Horizons, 66–73.

Rosenblatt, Z., & Peled, D. (2002). School ethical climate and parental involvement. Journal of Educational Administration, 40(4/5), 349–367.

Ryan, M., & Martinson, D. L. (1984). Ethical values, the flow of journalistic information and public relations persons. Journalism Quarterly, 61(1), 27–34.

Schein, E. H. (1984). Coming to a New Awareness of Organizational Culture – The Magazine - MIT. Sloan Management Review, 25(2), 2–15.

Schneider, L. A. (1985). The role of public relations in four organizational types. Journalism Quarterly, 62, 567–576.

Sinclair, A. (1993). Approaches to organizational culture and ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 12, 63–73.

Singhapakdi, A., & Vitell, S. J. (1990). Marketing ethics: Factors influencing perceptions of ethical problems and alternatives. Journal of Macromarketing (Spring), 4–18.

Stevens, B. (1999). Communicating ethical values: a study of employee perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics, 20(2), 113–120.

Tilley, E. (2005). The ethics pyramid: making ethics unavoidable in the public relations process. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 20(4), 305–320.

Trevino, L. K. (1986). Ethical Decision Making in Organizations: A Person-Situation Interactionist Model. The Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 601–617.

Trevino, L. K., Weaver, G. R., Gibson, D. G., & Toffler, B. L. (1999). Managing ethics and legal compliance: what works and what hurts. California Management Review, 41(2), 131–151.

VanSandt, C. V., Shepard, J. M., & Zappe, S. M. (2006). An examination of the relationship between ethical work climate and moral awareness. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(4), 409–432.

Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1987). A theory and measure of ethical climate in organization. Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy, 9, 51–71.

Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33, 101–125.

Vitell, S. J., & Davis, D. L. (1990). The relationship between ethics and job satisfaction: an empirical investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(6), 489–494.

Weaver, G. R. (1995). Does ethics code design matter? Effects of ethics code rationales and sanctions on recipients' justice perceptions and content recall. Journal of Business Ethics, 14, 367–385.

Weaver, K. M., & Ferrell, O. C. (1977). The impact of corporate policy on reported ethical beliefs and behavior of marketing practitioners. Paper presented at the Contemporary Marketing Thought: American Marketing Association, Chicago.

Werner, S. B. (1992). The movement for reforming American business ethics: A twenty-year perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 11, 61–70.

Wimbush, J. C., & Shepard, J. M. (1994). Toward an understanding of ethical climate: its relationship to ethical behavior and supervisory influence. Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 637–647.

White, B. J., & Montgomery, B. R. (1980). Corporate codes of conduct. California Management Review, 23(2), 80–87.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A. Scenarios of ethical dilemmas

Scenario 1

John is developing a promotion for a housing development his company is about to start. The development is located in a low area that was flooded recently. Consequently, John's company did some work to reduce the danger of flooding. However, if flooding occurs, some of the homes may have some water in their yards. John's company has no plans for additional work to reduce the possibility of flooding. John did not include in his promotion any information on the possibility of flooding.

Question: I would do just what John did.

Scenario 2

Laura is a senior account executive in the Public Relations Division of a leading advertising agency. Several months ago, her division signed a major account. Recently the client called to request an update on the account. Laura informed the client that the execution of the account had been delayed because the production department had been “bogged down.”

Fact: The account had been set aside in the meantime in preference for a newer, higher billing, higher profile account. Laura believes that telling the client the truth could place her agency in an awkward position with the client—and perhaps jeopardize all future business.

Question: I would do just what Laura did.

Scenario 3

Bob recently completed multi-thousand-dollar evaluation research on a corporate image promotion he had completed recently. Results indicated that the promotion did not produce the expected gains in corporate image. Bob's agency had been counting on those results for a continuation of its business relationship with the client.

Your research department said that the statistics “tell the truth” and that Bob was obligated to use them in his executive summary. Bob said, “No way. The numbers could be self-destructive.” He said that the numbers were only known in-house, and to use them now would “cost the agency big bucks and put us in an awkward position with our client.” In his report to the client, Bob used older, more flattering statistics from a previous survey, while awaiting the results of the next evaluation study.

Question: I would do just what Bob did.

Scenario 4

Frank, a senior public relations manager, was staying overnight on a business trip. He went into the hotel lounge to have a drink. He found himself seated next to another public relations manager from his leading competitor. The public relations manager, who appeared to have had several drinks, was in a talkative mood. He talked about his clients and divulged confidential information to Frank. Frank happened to handle the account of a competitive brand.

Frank did not identify himself and instead bought the other executive several more drinks, thinking that if he could not hold his liquor it was his problem. Frank received valuable confidential information about the competitor's new advertising campaign, marketing strategies, and other information that could sharply increase the profits of his own client.

Question: I would do just what Frank did.

Appendix B. Measurement items for each variable

Top management support for ethical behavior

-

1.

Top management in my public relations firm has clearly conveyed that unethical public relations practices will not be tolerated.

-

2.

Top management in my firm should have higher ethical standards for public relations practices than they currently have. (Reversed)

-

3.

If a manager in my firm is discovered to have engaged in unethical PR practices that result primarily in personal gain rather than corporate gain, he/she will be promptly reprimanded.

-

4.

If a manager in my firm is discovered to have engaged in unethical public relations practice, he/she will be promptly reprimanded even if the practice results primarily in the company's gain.

Ethical climate

Egoism

-

1.

My firm emphasizes the importance of furthering its interests.

-

2.

Public relations practitioners in my firm are expected to be concerned with the firm's interests all the time.

-

3.

All decisions and actions in my firm are expected to contribute to the firm's interests.

-

4.

Public relations practice that hurts my firm's interests may be acceptable. (Reversed)

Principle

-

1.

Compliance with the firm's ethics policy and procedures is very important in my firm.

-

2.

Public relations professionals in my firm are expected to strictly adhere to the organization's ethics policy.

-

3.

Public relations practitioners who do not follow the organization's ethics policy for their practices are viewed favorably in my organization. (Reversed)

-

4.

My firm does not emphasize the importance of ethics code, procedures, and policies for public relations practices. (Reversed)

Benevolence

-

1.

Concern for employees is prevalent in my firm.

-

2.

My firm emphasizes employee welfare.

-

3.

All decisions and actions in my firm are expected to result in what is generally best for everyone.

-

4.

My firm considers the well-being of all employees.

Association between ethical behavior and career success in the public relations firm

-

1.

Successful public relations professionals in my firm are more ethical than unsuccessful ones.

-

2.

In order to succeed in my firm, it is often not necessary to compromise one's ethics.

-

3.

Successful public relations professionals in my firm do not withhold information that is detrimental to their self-interest.

-

4.

Successful public relations professionals in my firm do not make their rivals look bad in the eyes of important people.

-

5.

Successful public relations professionals in my firm do not look for a “scapegoat” when they fear they may be associated with failure.

-

6.

Successful public relations professionals in my firm do not take credit for the ideas and accomplishments of others.

-

7.

Ethical public relations practices and behavior are important for success in my firm.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ki, EJ., Lee, J. & Choi, HL. Factors affecting ethical practice of public relations professionals within public relations firms. Asian J Bus Ethics 1, 123–141 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-011-0013-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-011-0013-1