Abstract

The environment and natural resource fields have traditionally centered western science, the scholarship of white men, and land conservation strategies that neglect historical inhabitants. These tenets have led to a narrow view of how conservation is defined and created challenges for BIPOC students and professionals to see themselves as full and equal participants in the environmental sciences. The Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources has worked to address these shortcomings through courses designed to address issues of systemic racism and exclusion in the environmental field. In our student’s first year, we pair a fall course focused on communication skills with a spring course that addresses issues of racism and social justice in the environmental fields. We use the fall semester to create a learning community where students build relationships of trust, mutual regard, and care and develop a deeper understanding of their relationship with the environment. In the spring, we present students with a variety of frameworks to think critically about equity, inclusion, positionality, privilege, racism, and diversity. A key learning outcome is to help students consider how historical and present-day dynamics of race and racism have shaped the environmental field. Importantly, we focus on the voices and messages of environmental leaders who have historically been left out of popular environmental narratives. We outline lessons learned in the integration of diversity, equity, and inclusion into our environment and natural resources curriculum and ways to further enhance our centering of equity and inclusion in the curriculum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the USA, the mainstream environmental field is dominated by the histories, voices, research, and perspectives of white people, which has shaped both the agenda of environmental organizations, agencies, and their boards (Taylor 2014; Hadella et al. 2023), as well as the way in which environmental and natural resource curricula are delivered (Taylor 1996, Stapleton 2020, Cronin et al. 2021). Environmental curricula typically focus on western science (Kimmerer 2002), celebrate the accomplishments of white men (Dorsey 2001), and tend to focus on environmental conservation rather than issues of environmental justice (Gould et al. 2018, Rudd et al. 2021). These perspectives preference a single way of understanding “environment” (Stapleton 2020) and disenfranchise students from non-white identities who do not see themselves included in the environmental field (Taylor 2014). The lack of diverse voices and perspectives in the environmental field leads to a narrow view of how environmental issues are framed and prioritized (Gould et al. 2020).

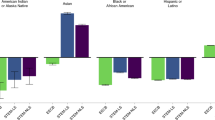

Over the last 30 years, more students who identify as BIPOC have pursued higher education but are not enrolling in environmental majors proportional to this increase (Sharik et al. 2015). Academics and professionals in the environmental fields have sounded alarm bells over the small populations of BIPOC students (Taylor 2014) and many recommend best practices to attract diverse students. These initiatives often fall short as they rarely take into account the lived experiences and perspectives of BIPOC students with regard to the environment and natural world. The changing demographics of the population of college-aged students, racial composition of this population of students, and their actual college experience are some of factors that influence the enrollment and retention of BIPOC students. The low enrollments of BIPOC in natural resource programs pose a few problems: an absence of diverse experiences and perspectives within the classroom as well as a workforce that does not represent the demographics of the USA or globally. From fall 1976 to fall 2015, the percentage of American college students who were Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Black increased (ranging from 2 to 17% among these racial groups but only 0.7% among Native American students). At the same time, the general population of the USA is experiencing a shift from majority white to majority Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (Frey 2018; Vespa et al. 2020). There are and will be more BIPOC students attending college, but they do not appear to be enrolling in natural resources programs proportional to the increase in population. As current professionals age out of their careers, there will not be a diverse workforce that reflects the general population to replace them.

BIPOC students experience university quite differently from white students and they are treated differently than their white peers (Eimers and Pike 1997; Suarez-Balcazar et al. 2003; Chang et al. 2014). The observed bias of mainstream identity students toward certain issues as named above rather than issues that disproportionately affect BIPOC communities renders the classroom a site for exclusion rather than inclusion. Geographer David Delaney (2002) suggests that places like urban environments and National Parks are racialized geographies that serve to maintain structures of domination, subordination, and inequality. Race and space have “longstanding historical roots in the process of imperialism – racializing bodies and groups has always been linked to the theft of land and the control of space” (Winant as cited in Neely and Samura 2011). These troubled spaces exist in learning environments and university spaces. A study conducted by Harwood et al. (2018) explored the lived experiences of BIPOC students in university “representational spaces” described as fortified: a space of white dominance where People of Color often experience explicit racism; contradictory: a space of covert racial dominance where People of Color regularly experience being treated as second-class citizens; and counter: a space created as an act of resistance or survival for People of Color but one that also faces opposition. The fortified and contradictory spaces echo the experiences of BIPOC students as they navigate the environment and natural resources curriculum and University of Vermont.

As educators, we have a responsibility and the opportunity to change our curriculum and pedagogy in response to the long-standing and increasing body of evidence highlighting inequities in our field (Cronin et al. 2021), and the moral and instrumental challenges raised by these inequities. We have a moral responsibility to recognize, account for, and counter the unequal treatment of people based on societal and demographic divisions. In addition, we meet an instrumental challenge of making our curriculum and school relevant to a broader array of people by understanding diverse relationships to nature and reckoning with the racist history of the environmental field and the scientific method. We hope to contribute in a meaningful way to the capacity of all students to work effectively in a multicultural world and create an inclusive environment for BIPOC students.

In the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources (RSENR) at the University of Vermont (UVM), we have worked to address these issues in our environment and natural resource curriculum by centering inclusion and equity as frameworks to address environmental challenges. We begin with the premise that issues of equity are inherent in all environmental and natural resources challenges (Halpern et al. 2013). In cases of blatant environmental racism, distribution of toxic wastes and pollution have direct impacts on quality of life and lifespan of BIPOC community members (Bullard et al. 2007). Other equity issues are more subtle and may involve access to green spaces (Pelletier 2010), access to decision-makers (Hillier 1998), funding for community projects (Larson and Ribot 2007), and the ways in which environmental issues are prioritized (Potapchuk et al. 2005; Bonta and Jordan 2007). We argue that without centering equity as the key tenet of environmental problem solving, we will not be able to address holistically our most pressing environmental issues.

In this paper, we describe the goals and learning outcomes of our two first-year courses and to put these goals in the context of delivering content on systemic and environmental racism within a predominately white institution. We highlight some of the lessons that we have learned in developing and delivering these courses. We still have challenges to address, and we explore some unresolved issues in the discussion. We hope by describing our approach to integrating diversity, equity, and social justice into our program, we can provide a framework for other environment and natural resource programs seeking to change their curricula by describing our successes and missteps.

Background

UVM is a predominately white institution, with roughly 88% of the undergraduate population being white and the RSENR being whiter than the rest of campus (92%). Vermont is also a predominately white state (89.7%), and although 73% of undergraduate students come from out-of-state, 62% are from the New England region (including Vermont), which is also majority white (U.S. Census Bureau 2022).

Over the last 30 years, the faculty in RSENR have been working to incorporate issues of diversity and social justice into the school’s environment and natural resources curriculum. These efforts are grounded in a model of shared faculty, staff, and student learning. Our knowledge and understanding changes over time as our lived experiences and the social and cultural context change. We build on these changes in the courses we teach, and the curriculum more generally. Over time, we have drawn on relationships with people inside and outside of the university that have been critical to our learning and capacity to meet our curricular goals. Additional changes to our curriculum have been influenced by student activism. Student protests have centered on curricular reforms, recruitment and retention of students and faculty of color, and increased resources for student clubs and affinity centers. New faculty hires with new perspectives as well as events internal and external to campus have also shaped our curriculum.

In 1993, we created a 1-credit course for incoming first-year students (Race and Culture in Natural Resources) in the RSENR core curriculum which was required for students in all majors in the school (environmental science; forestry; parks, recreation, and tourism; sustainability, ecology, and policy; and wildlife and fisheries biology). The format of the course was tied to first-year advising: faculty facilitated discussion sections with their own advisees focused on course content. This has evolved to two courses required during the first year, and the infusion of diversity and environmental justice throughout our core curriculum, which consists of eight courses in total. In addition, diversity and environmental justice issues have been integrated into some of the major-specific curricula. In this paper, we describe our experiences, practices, challenges, and lessons learned related to the two first-year courses: a 1-credit course in the fall semester to develop relationships in small discussion groups and build critical reflection and dialogue skills (Critical Reflection and Dialogue), and a 3-credit course in the spring semester to raise and address dimensions of power, privilege, and systemic racism as they relate to environment and natural resources (Race and Culture in Natural Resources). Students simultaneously take a sequenced two-semester 4-credit course in the fall and spring of their first year (Natural History and Human Ecology 1 and 2). These courses include content formerly covered in Race and Culture in Natural Resources about the history of the conservation movement (Powell 2016). This includes aspects of identity, power, and privilege in dominant narratives about the movement (Rudd et al. 2021), and connections between leaders of the conservation movement and the eugenics movement (Burton and Ruppertt 1999, Kantor 2007, Allen 2013).

Course structure

Critical reflection and dialogue

The introductory course, “critical reflection and dialogue,” focuses on community-building and two specific skills: writing (critical reflection) and speaking/listening (dialogue). Students meet for 1 h per week in small groups (typically 20 students) with a faculty member who has skills in facilitating dialogue. We use the topics of place, screens, and stuff (material goods) to develop competence in students’ skills for critical reflection and dialogue. These topics are relevant for our students and connect to some of their interests in the environmental field.

The learning objectives for the course are for students to:

-

1.

build relationships of trust, mutual regard, and care with each other and a RSENR faculty member through conversations and group activities.

-

2.

use critical reflection to develop a deeper understanding of themselves, their communities, and social-ecological systems.

-

3.

develop dialogue skills as a means to listen to and empathize with diverse perspectives.

-

4.

develop a deeper understanding of their unique perspective, including past and present influences on their knowledge, reactions, and assumptions.

Our goal is to prepare students for more challenging conversations in the spring semester course. As such, we do not address issues of equity and diversity in the environmental field specifically. We use a cohort model in which students remain in the same groups in the spring semester as they transition into “race and culture in natural resources.” This allows students to gain trust and build community around environmental topics of interest and use that as a foundation to generate a space in which they can talk more openly about environmental racism, as well as issues of equity and identity in the environmental field.

We emphasize the difference between dialogue and debate (Ellinor and Gerard 1998) and expect students to focus on dialogue as an opportunity to learn, rather than to convert others to one’s own point of view. For example, we work with students to develop probing questions that take conversations deeper, not necessarily to develop solutions, but to come to a greater understanding of diverse perspectives.

We use a similar approach in directing student writing. We contrast a journalistic approach of recounting the facts with a reflective approach of exploring what is relevant and important to each student and their experiences. Our critical reflection approach uses the “what, so what, now what?” framework of critical reflection (Rolfe et al. 2001) to think more deeply about the relevance of the course content in their own lives. We leverage these practices of dialogue and critical reflection in the spring semester as we turn our focus to race and racism in the environmental field.

Race and culture in natural resources

In the spring semester, students enroll in “race and culture in natural resources.” The class meets twice weekly, with one session for a plenary lecture, and one session to debrief about the content from the lecture in the same discussion group with the same facilitator as in the fall semester. By maintaining the same discussion groups and facilitators, we seek to create continuity and a sense of community in which students can be comfortable and open in addressing the course content. The learning outcomes for the course are to:

-

1.

use a variety of frameworks to think critically about equity, inclusion, positionality, privilege, racism, and diversity.

-

2.

use critical reflection and dialogue to better understand and empathize with diverse perspectives on environment and natural resource issues.

-

3.

evaluate to what extent solutions to environmental issues are equitable with respect to race, gender, socioeconomic class, and other dimensions of difference.

-

4.

describe some dynamics of race, racism, and anti-racism in historical and present-day environmentalism.

-

5.

learn from the stories and voices of environmental leaders who have historically been marginalized from popular environmental narratives.

The course builds on the foundations of communication from the fall semester and introduces students to a variety of frameworks that help them understand issues of identity, power, and in particular, race and racism in the environmental field. The arc of the course includes three units that build upon one another.

-

1.

Foundations and Frameworks, in which we introduce students to (for example) social identities, the 4 I’s of oppression (Bell 2013), the cultural iceberg (Hall 1976), and the mythical norm (Lorde 1984). Additionally, we define key terms to ensure students share a common language around issues of race, racism, culture, and equity, and highlight the origins of the construct of race.

-

2.

Environmental Justice, in which we define environmental racism/injustice and justice, concepts of power, and the institutional settings in which environmental racism and justice have been defined in the USA. We consider connections among racism, appropriation of land, labor, and liberty, redlining, and how these histories show up in approaches to nature and environmental work today, including the disproportionate distribution of environmental burdens and benefits. We also highlight the procedural aspects of environmental justice issues, and how these are tied into policy responses.

-

3.

Vision and Change, in which students consider theories of change, privilege as practice (Kolan and TwoTrees 2014), how various individuals and organizations are approaching change in work where environment and equity intersect; students also develop their own personal vision and theory of change in the realm of environmental endeavors.

Both instructors and students must be able to describe their own identity and their relative levels of privilege and power. When we have conversations about systemic and environmental racism, it is easy for students to become overwhelmed with the enormity of the challenges and develop feelings of anxiety when coming to a deeper understanding of their own privilege. By creating an opportunity for students to consider their own identity and the ways in which they can interrogate their own biases and actions, students can begin to see self-transformation as a way to enact change.

One of the key frameworks that we introduce is an equity lens (McDermott et al. 2013). We believe that sustainable solutions to environmental challenges must incorporate equity in a holistic and meaningful way. Understanding the inequities in the distribution of environmental costs and benefits is a central component of the course. Our lens asks students to address people (who is impacted), place (spatial distribution of public resources), process (policies, relationships, and systems contributing to inequities), and power (who makes decisions and who is accountable) when considering solutions to environmental issues. The equity lens can be a powerful tool for students to be able to think through the ways in which groups disproportionately lose or gain depending on a particular intervention. This framework also serves as a means by which students can deepen their critical reflection skills.

In a predominately white institution, white authors and viewpoints are most likely to be privileged (Harper and Hurtado 2007). We have adopted the book The Colors of Nature: Culture, Identity, and the Natural World (Deming and Savoy 2011) to expose students to environmental writing that interrogates historical and contemporary places and issues from a BIPOC lens. The book delves into the interrelationships between humans and the environment that can be painful, but also shows connections that are different and often deeper than those of white colonizers. The essays provide students with a diversity of perspectives on relationships with nature, enabling them to delve deeply into how their identity and past experiences shape the ways in which they think about nature. Many of the essays also use poetry and metaphor, meaning they tap into a richer landscape of relationships and also multiple ways of knowing about nature. The book introduces students to a wide array of perspectives on racial, ethnic, and cultural connections to the environment. Consequently, the essays in this book enable us to highlight BIPOC experiences without environmental leaders of color serving as the curriculum.

Keys to improving learning outcomes

As we developed learning outcomes for the RSENR core curriculum, we assessed our signature assignment in Race and Culture in Natural Resources against our working across difference rubric (Burke et al. 2018). We found poor alignment and reorganized the course structure such that learning outcomes could be assessed multiple times throughout the semester. We currently assess course learning outcomes through mapping exercises, poster presentations, writing logs, and critical reflections, with each having direct ties to the learning outcomes. Some example questions we ask students to address in these assignments include:

-

How does the emphasis on the conservation of wilderness affect how the “environmental movement” and “nature” are defined and framed? (Learning outcome 2)

-

How has/will the connection between historical redlining and links to current and past environmental racism in the USA changed the way you prioritize environmental issues? (Learning outcome 3)

-

What stories are missing from the “mainstream” or “traditional” environmental movement that are included in the environmental justice movement? (Learning outcome 5)

Perhaps the most important step we have taken in course design is to move from a single course on race and culture in natural resources taken during the first semester to a two-semester sequence in which we separate building relationships and communication skills from learning about environmental racism and justice. This change has helped us to achieve the learning objectives for both courses. It also follows a developmental model in which students have time to become accustomed to college life before engaging with more challenging topics. Enabling students to form a community and build their communication skills in a relatively low-risk environment has enhanced their ability to take on the more challenging issues of race and racism in their second semester. By seeding the fall semester with skill building centered on critical reflection and dialogue, the students have tools to better navigate the complex interactions of race and environmental equity.

Another important shift has been a transition away from a single lead instructor to one in which each of the ten co-facilitators take responsibility for delivering content in our large lecture classes. This shift has led to several important improvements in the course. First, students see their own facilitator as being an important part of the teaching team, rather than just the facilitator of their small group discussions. Second, this has led to greater buy-in among the co-facilitators as they are responsible for creating connections to past course content as well as providing a foundation for subsequent facilitators to build from. Additionally, this approach has lessened the burden on a single instructor for “carrying the course.” While one faculty still oversees the logistics of the course, they are not responsible for content creation and delivery on a weekly basis.

In addition to a shift in workload for co-instructors, in the most recent offering of the course, three of the ten co-instructors identified as BIPOC as well as many of our guest speakers, most of whom reside in Vermont and are themselves leaders in the environmental movement. Again, this widens the field of perception for majority white students and perhaps more importantly, BIPOC students see themselves reflected among the teachers and practitioners (Taylor et al. 2022).

Finally, for both courses, the facilitators meet weekly to provide general consistency in small group activities from week to week. Facilitators still have agency to create their own lesson plans, but sharing ideas for activities and resources to use in the small group sessions has allowed us to memorialize the most impactful activities as well as provide a support network for faculty who are teaching the course for the first time. These weekly meetings have enabled the facilitators to create a space for sharing best practices around engaging students and facilitating dialogue.

Ongoing challenges

Although we believe these courses have created a foundation for students to better understand the legacy of racism and inequities in the environmental field, we still have several challenges to address.

Dialogue

We have found that our students gain competence with critical reflection relatively quickly. They are able to assimilate new information, synthesize it, assess its relevance, and consider how they might integrate this new understanding moving forward. However, parallel gains in competency with dialogue are not as strong. Our learning outcome around dialogue states that students will use this opportunity to form probing questions that can create a foundation to deeper learning and understanding multiple perspectives. Here we have found several issues that continue to be challenging. First, students are not well disciplined in monitoring their contributions to the conversations, resulting in dominant voices overshadowing others who are reluctant to engage in the dialogue. Second, students continue to be challenged to avoid a debate-type format, or to simply use dialogue to reiterate good ideas to which they have been exposed. We have tried to address these issues in several ways. We have created “dialogue plays” in which students take roles in a conversation about one of their assigned readings with the goal of helping them find their voice in their small groups. Additionally, we have used free writes and pair shares to allow students an opportunity to gather their thoughts prior to engaging in dialogue. Additionally, we have used the first semester to build community agreements. If not brought up by the students, we suggest including “accept and expect non-closure,” which has been a helpful guiding principle; nevertheless, many students continue to want a more concrete endpoint to their conversation. Finally, we have purposefully delivered this course to first-year students so that they have the subsequent 3 years to consider how the issues of race and racism impact the environmental field. However, first-year students are still building their social networks and as a result, there is some reluctance to challenge the perspectives of their peers for fear it may impact relationships outside of the classroom.

Infusion throughout the curricula

The simple presence of these two courses in our curriculum has allowed faculty to integrate the pedagogy, content, and experiences into classes they teach in their respective disciplines. However, we are only beginning to see this content infused into upper-level classes. We have developed a rubric for the RSENR core curriculum called “working across difference,” (Burke et al. 2018) which includes learning outcomes that address identity development, intercultural competence, power, and privilege, and engaging with tension. Although these learning outcomes are all addressed in these two first-year courses, they are not addressed evenly across the RSENR’s five majors. This has led to variability in the level of competence of our graduates, with students in majors more focused on natural sciences having less exposure to topics of diversity, equity, and inclusion. This is despite the fact that all the majors in RSENR have program-level learning outcomes that address social justice and equity. We know that if we do not integrate issues of racism, white supremacy, and equity with environmental issues, we will continue to be challenged to make the environmental field more inclusive.

Racism in altruism

Many students arrive in RSENR with a “save the world” mentality. We do not want to diminish this spirit, but we do want students to understand that the way in which they define “saving the world” can have consequences for how they define their careers. In particular, we want students to be able to apply an equity lens to saving the world so that they are considering the people, places, processes, and power dynamics inherent in how environmental issues are framed and prioritized. Despite asking students to interrogate the ways in which their identities and experiences affect their biases around conservation and environmentalism, we still see students preferencing, for example, wilderness conservation and endangered species over safe drinking water, or issues with air quality around industrial facilities. Reconciling the fact that “saving the world” can still be linked to systemic racism continues to be a challenging notion for our students (Bratman and DeLince 2021). Mainstream white environmentalism does not “see” or make space for different experiences of place and relationship to land. As Dr. Dorceta Taylor observes, the truth is that majority identity environmentalists speak from lived experience of nature with a “focus on the birds, trees, plants, and animals, because they don’t have the experience of being barred from parks and beaches” (Taylor as quoted in Mock 2014).

BIPOC student experience

When interviewed about their experiences in the Rubenstein School diversity curriculum, a small group of BIPOC RSENR alumni identified several dynamics. For instance, the predominant stories we tell about “what is environmentalism” or “who is an environmentalist” preferences certain landscapes and experiences. Furthermore, inherent in these stories are assumptions of what outdoor knowledge and codes of conduct are acceptable or admired. These stories often erase or marginalize the experiences of BIPOC students. Language, cultural messages, and visual cues act as boundaries. Learning to traverse these boundaries requires its own field guides and maps that are not readily apparent or accessible to everyone. Alumni expressed a sense that there is a set of “instructions” regarding how to be in the outdoors. While many of their college peers knew the landscapes, the outdoor lingo, the codes of behavior, and the attire, BIPOC students felt ostracized for not knowing. Power dynamics manifest at university as preferred experience, bodies of knowledge, language, and gear that make the journey easier for some but may create undue burdens on others. Mainstream environmentalism places a higher value on certain ideas of nature; BIPOC students must learn the content and skills to navigate the dominant culture, like learning another language and modes of travel (Vea 2020).

As a predominately white school in a predominately white campus, the narrative of the course can feel like we are only trying to get white students to recognize their privilege and to broaden what is often a narrow view of the environmental field. To counter this narrative, we have tried to construct the class in a way that enables all students to evaluate their own relative degrees of privilege and apply this analysis to their own systems (friends, family, dormitory, clubs, etc.) to understand where they have agency (Kolan and TwoTrees 2014). Despite this central premise, we still see the course creating challenges for BIPOC students including feeling othered, victimized, or that they need to speak for their identity group. This lived experience of BIPOC students in Race and Culture in Natural Resources reflects the experience of the larger population, that is, whiteness pervades all, is centered in spaces, in curricula, and in activities. The intention of a course like Race and Culture in Natural Resources is to make visible and to dismantle these dynamics although the impact upon all our students can be uneven and difficult to measure.

We have taken several steps to try to address these issues. First, when we have students consider potential career paths in the environmental field, we have asked them to reflect on what it means to be an inclusive environmentalist. Our goal is for students to realize that the first step in creating a more inclusive and welcoming field is to examine our own biases and stereotypes. Second, when (white) students learn about environmental racism (e.g., hazardous waste disposal, inequitable distribution of green spaces), they may create assumptions about the background of BIPOC students in the class. We have tried to counter this narrative by helping students see the diverse ways that people interact with the environment such that particular ways of knowing and being are not tied to racial identity. Finally, through readings, videos, and guest speakers, we use resources that amplify the voices of BIPOC environmental leaders so students in the class do not feel as though they need to be a spokesperson for their race, culture, or ethnicity. Recent advances in the capacity of remote access to a wider range of instructors can be used to expand the voices to whom students are exposed. To this end, we have also set aside funds for honoraria to ensure that BIPOC professionals are fairly compensated for their time.

A similar issue has been brought up by students with respect to the facilitators in the course, who are also majority white. Students feel that our BIPOC faculty should be the ones who are telling students about their lived experiences; an outgrowth of white privilege in which students feel empowered to hear these stories from faculty. We have grappled with this challenge at a variety of levels. First, we do not want to put BIPOC faculty in a position where they are the ones who are required to teach classes about the intersection between race and the environment. For some, this may be their scholarly discipline, but for other faculty this is simply perpetuating a stereotype. All facilitators address their positionality, their identities, and how that influences their biases and stereotypes. And we are cognizant that if we do not show students that despite our roles as faculty, we still need to learn and continue to be open to honest critiques from students and our peers. Critiques from both students and colleagues have been invaluable to course facilitators as we have been able to continually improve upon course content and the student experience.

A final challenge in each offering of the class revolves around the question of “what can I do?” In the final section of the course, we focus on change. As noted above, we start with the individual student: ensuring that students understand their own privileges and biases and can think critically about integrating equity into environmental problem solving. For white students, we want them to understand that although they are not responsible for systemic racism in the country, they are privileged through the structures that continue to be entrenched in US society. For BIPOC students, we want to create learning conditions that do not harm, that demonstrate our intention to interrogate the conventional narratives related to the environment and in turn lift up the stories that have historically erased BIPOC so that they might begin to see their own agency and privilege across a variety of systems. At a broader level, we emphasize the importance of working collectively to learn about and take steps to contribute to change over time. In so doing, we challenge a myth of individualism, and instrumentalism, that is, “I can do this on my own” and “I expect to see results immediately.” In addition, we identify varied paths for contributing to change, where students can bring their own strengths and passions to the table.

Conclusion

Through our redesign of these two courses, we have been successful in creating learning communities where students can undertake engaged dialogue around the racist history of the environmental movement and the legacy of redlining on the distribution of environmental benefits and burdens. The fall course has provided a foundation for students to consider past and present influences on their knowledge and assumptions to develop a deeper understanding of their unique perspectives. Combined with better developed skills around critical reflection and dialogue, students can interrogate structures that perpetuate systemic racism in the environmental arena. As we move into the spring semester, students receive an introduction to a breadth of issues that are central to the environmental justice field, but are marginalized in the field of environmental conservation. By asking students to examine their assumptions about what “counts” as environmentalism, students take a more holistic approach to environmental problem-solving by centering equity when addressing environmental challenges. We know that emphasizing the work of environmentalists of color alone will not lead to a more diverse student body. However, by broadening the conservation narrative, students can see how prioritization of financial resources, priorities, places, and populations can negatively impact BIPOC communities.

The last several years have seen a substantial increase in papers and books outlining anti-racist practices that can be implemented in higher education, including the geosciences (Hall et al. 2022), ecology and evolution departments (Cronin et al. 2021), STEM education (Goldberg et al. 2023), research labs (Chaudhary and Behre 2020) and mentoring practices (Marshall et al. 2022). Although we implemented many of the structural changes in these courses prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, our work follows many of the same anti-racist practices that others have suggested. These include normalizing dialogue about racism, amplifying voices of BIPOC environmental leaders, intentional recruitment of BIPOC faculty, staff, and students, and ensuring leadership is accountable for operationalizing anti-racist policies and decisions. In the classroom, regardless of student racial and ethnic identity, we implement a growth mindset, knowing that discovery of the racist history of the environmental movement is challenging for students. Aligned with best practices for inclusive teaching (Hogan and Sathy 2022), we have diversified the ways in which students can demonstrate mastery of course content, and have incorporated active learning (dialogue, in particular) to enhance student’s ability to internalize readings and lecture material.

When we implemented changes to these courses, one important, yet unanticipated improvement in the course was the buy-in from course facilitators around shared responsibility for content delivery. The community of practice that has emerged among co-facilitators has improved the arc of the course content, assignment design, and dialogue facilitation, while minimizing the burden on any individual instructor. The many instructors and students who have been involved in these courses over the last several decades have spent considerable time and collective reflection to evolve learning outcomes, pedagogy, skills-development, the application of frameworks, and teaching technologies to arrive at the current iteration of these courses. This is still a work in progress. The version presented here marks one specific point in time; however, classes and curricula are never truly “finished,” but continual works in progress. The addition of many more BIPOC voices and stories is an important and meaningful addition—representation means something—and it is one of many necessary and intentional actions to create a more inclusive learning experience.

References

Allen GE (2013) Culling the herd: Eugenics and the conservation movement in the Unites States, 1900-1940. J Hist Biol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-011-9317-1

Bell J (2013) The Four “I’s” of Oppression. https://www.beginwithin.info/articles-2/. Accessed 16 Jun 2024

Bonta M, Jordan C (2007) Diversifying the American environmental movement. Pages 13–33 in Enderle E (ed). Diversity and the Future of the U.S. Environmental Movement. Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, New Haven, CT. https://www.elischolar.library.yale.edu/fes-pubs/1/. Accessed 16 Jun 2024

Bratman EZ, Delince WP (2021) Dismantling white supremacy in environmental studies and sciences: an argument for anti-racist and decolonizing pedagogies. J Environ Stud Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-021-00739-5

Bullard RD, Mohai P, Saha R, Wright B (2007) Toxic wastes and race at twenty 1987–2007: grassroots struggles to dismantle environmental racism in the United States. United Church of Christ Justice and Witness Ministry, Cleveland OH. https://www.ucc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/toxic-wastes-and-race-at-twenty-1987-2007.pdf. Accessed 16 Jun 2024

Burke M, Poleman W, Strong A (2018) Core curriculum revitalization report: rubric for working across difference. https://www.uvm.edu/sites/default/files/Rubenstein-School-of-Environment-and-Natural-Resources/Rubric_2Rev.2.6.18.pdf. Accessed 27 Apr 2024

Burton L, Ruppertt D (1999) Bear’s lodge or devils tower: intercultural relations, legal pluralism, and the management of sacred sites on public lands. Cornell J Law Public Policy 8:201–247

Chang MJ, Sharkness J, Hurtado S, Newman CB (2014) What matters in college for retaining aspiring scientists and engineers from underrepresented racial groups. J Res Sci Teach 51(5):555–580. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21146

Chaudhary VB, Berhe AA (2020) Ten simple rules for building an antiracist lab. PLOS J Comp Biol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008210

Cronin MR, Alonzo SH, Adamczak SK et al (2021) Anti-racist interventions to transform ecology, evolution and conservation biology departments. Nat Ecol Evol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01522-z

Delaney D (2002) The space that race makes. Prof Geog. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00309

Deming AH, Savoy LE (2011) The colors of nature: culture, identity, and the natural world. Milkweed Editions, Minneapolis, MN

Dorsey JW (2001) The presence of African American men in the environmental movement (or lack thereof). J African Amer Men. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-001-1003-5

Eimers MT, Pike GR (1997) Minority and nonminority adjustment to college: differences or similarities? Res Higher Ed. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024900812863

Ellinor L, Gerard G (1998) Dialogue: rediscover the transforming power of conversation. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, NY

Fairhead J, Leach M, Scoones I (2012) Green grabbing: a new appropriation of nature? J Peasant Stud 39:237–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.671770

Frey WH (2018) The U.S. will become ‘minority White’ in 2045, Census projects. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/03/14/the-us-will-become-minority-white-in-2045-census-projects/. Accessed 19 Apr 2023

Goldberg ER, Darwin TK, Esquibel JS, Noble S et al (2023) Contemporary debates on equity in STEM education: takeaways from a doctoral seminar in equity in STEM education. J Res in Sci Math Tech Ed. https://doi.org/10.31756/jrsmte.214SI

Gould RK, Phukan I, Mendoza M, Ardoin NM, Panikkar B (2018) Seizing opportunities to diversify conservation. Cons Lett. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12431

Gould RK, Bremer LL, Pascua P, Meza-Prado K (2020) Frontiers in cultural ecosystem services: toward greater equity and justice in ecosystem services research and practice. Biosci. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biaa112

Hadella L, Rapp C, Arismendi I et al (2023) An examination of race/ethnicity, gender, and employer affiliations on university natural resource program advisory boards. J Environ Stud Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-023-00852-7

Hall ET (1976) Beyond culture. Anchor Books, New York, NY

Hall CA, Illingworth S, Mohadjer S, Roxy MK et al (2022) Diversifying the geosciences in higher education: a manifesto for change. Geosci Comm. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2022-116

Halpern BS, Klein CJ, Brown CJ et al (2013) Achieving the triple bottom line in the face of inherent trade-offs among social equity, economic return, and conservation. Proc Nat Acad Sci. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1217689110

Harper SR, Hurtado S (2007) Nine themes in campus racial climates and implications for institutional transformation. New Direct Student Serv. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.254

Harwood SA, Mendenhall R, Lee SS et al (2018) Everyday racism in integrated spaces: mapping the experiences of students of color at a diversifying predominantly White institution. Ann Am Assoc Geog. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1419122

Hillier J (1998) Beyond confused noise: ideas toward communicative procedural justice. J Planning Educ Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9801800102

Hogan KA, Sathy V (2022) Inclusive teaching: strategies for promoting equity in the college classroom. West Virginia University Press, Morgantown, WV

Kantor I (2007) Ethnic cleansing and America’s creation of national parks. Public Land Res Law Rev 28:42–64

Kimmerer RW (2002) Weaving traditional ecological knowledge into biological education: a call to action. BioSci. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0432:WTEKIB]2.0.CO;2

Kolan M, TwoTrees KS (2014) Privilege as practice: a framework for engaging with sustainability, diversity, privilege, and power. J Sust Ed 7:1–14

Larson AM, Ribot JC (2007) The poverty of forestry policy: double standards on an uneven playing field. Sust Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-007-0030-0

Lorde A (1984) Sister outsider. Crossing Press, Berkeley, CA

Marshall AG, Vue Z, Palavicino-Maggio CB et al (2022) The role of mentoring in promoting diversity equity and inclusion in STEM Education and Research. Pathog Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/femspd/ftac019

McDermott M, Mahanty S, Schreckenberg K (2013) Examining equity: a multidimensional framework for assessing equity in payments for ecosystem services. Environ Sci Pol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.10.006

Mock B (2014) Are there two different versions of environmentalism, one “white,” one “black”? Grist. https://grist.org/climate-energy/are-there-two-different-versions-of-environmentalism-one-white-one-black/ Accessed 19 April 2023

Neely B, Samura M (2011) Social geographies of race: connecting race and space. Ethnic Racial Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.559262

Pelletier N (2010) Environmental sustainability as the first principle of distributive justice: towards an ecological communitarian normative foundation for ecological economics. Ecol Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.04.001

Potapchuk M, Leiderman S, Bivens D, Major B (2005) Flipping the script: white privilege and community building. Center for Assessment and Policy Development. https://www.mpassociates.us/uploads/3/7/1/0/37103967/flippingthescriptmostupdated.pdf. Accessed 17 Jun 2024

Powell MA (2016) Vanishing America: Species extinction, racial peril, and the origins of conservation. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Rolfe G, Freshwater D, Jasper M (2001) Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke UK

Rudd LF, Allred S, Ross JGB et al (2021) Overcoming racism in the twin spheres of conservation science and practice. Proc Royal So B. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.1871

Sharik TL, Lilieholm RJ, Lindquist W, Richardson WW (2015) Undergraduate enrollment in natural resource programs in the United States: trends, drivers, and implications for the future of natural resource professions. J Forestry. https://doi.org/10.5849/jof.14-146

Stapleton SR (2020) Toward critical environmental education: a standpoint analysis of race in the American environmental context. Environ Ed Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1648768

Suarez-Balcazar Y, Orellana-Damacela L, Portillo N et al (2003) Experiences of differential treatment among college students of color. J High Educ 74(4):428–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2003.11780855

Taylor DE (1996) Making multicultural environmental education a reality. Race Poverty Environ 6:3–6

Taylor AM, Hernandez AJ, Peterson AK et al (2022) Faculty diversity in California environmental studies departments: implications for student learning. J Environ Stud Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-022-00755-z

Taylor DE (2014) The state of diversity in environmental organizations. Green 2.0 working group. https://www.diversegreen.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/FullReport_Green2.0_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 40 Apr 2023

U.S. Census Bureau (2022) 2020 census results. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade/2020/2020-census-main.html Accessed 19 April 2023

Vea MC (2020) Sense of place and ways of knowing: the landscape of experience for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in natural resources, environmental education, and place based learning. (Dissertation), The University of Vermont and State Agricultural College

Vespa J, Armstrong DM, Medina L (2020) Demographic turning points for the United States. US Census Bureau https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.html Accessed 28 May 2020

Acknowledgements

Over the last 30 years, we have received inspirational assistance from numerous colleagues and friends. Don DeHayes and Deane Wang initiated the original course and helped shepherd it through its early phases. Sherwood Smith, Anna Smiles-Becker, Emilie Riddle, and Dot Brauer have been instrumental in improving many aspects of the course. TwoTrees, Shadiin Garcia, Brian Hsiang, Mohamad Chakaki, Bindu Panikkar, and Rachelle Gould have served as important mentors and co-facilitators. Student voices and activists have been important in shaping our DEI work, including Sonya Buglion Gluck, Kirsti Carr, Kunal Palawat, Sumana Serchan, Nichole Henderson, Nathaly Agosto Filion, Joshua Carrera, Alejandro Vinueza, Flore Costume, Jennifer Gil, and Rebecca Gonzalez. Mickey Finn, Carolyn Finney, and Matt Kolan have been invaluable leaders in integrating diversity, equity, and inclusion work into our environmental curriculum. Finally, we thank the Rubenstein community for their openness and willingness to embrace challenging conversations.

Land acknowledgement

The campus of the University of Vermont sits within a place of gathering and exchange, shaped by water and stewarded by ongoing generations of Indigenous peoples, in particular the Western Abenaki. Acknowledging the relations between water, land, and people is in harmony with the mission of the university. Acknowledging the serious and significant impacts of our histories on Indigenous peoples and their homelands is a part of the university’s ongoing work of teaching, research, and engagement and an essential reminder of our past and our interconnected futures for the many of us gathered on this land. UVM respects the Indigenous knowledge interwoven in this place and commits to uplifting the Indigenous peoples and cultures present on this land and within our community.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Marie Vea’s doctoral research referenced in this manuscript was reviewed and approved by the University of Vermont’s Research Protection Office (IRB number 00000485).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Strong, A.M., Vea, M.C., Ginger, C. et al. Teaching and learning about race, culture, and environment in a predominately white institution. J Environ Stud Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-024-00948-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-024-00948-8