Abstract

Urban organic wastes (UOW) strain the infrastructures for solid waste treatment (SWT) in emerging economies. This study investigated biochar gained from three major UOW sources in India—banana peduncles (BP), a fibrous waste, from fruit markets; sewage sludge (SS) from wastewater treatment plants; and anaerobic digestate (AD) from food and market waste processing facilities—in terms of its potential to sequester and become long-term carbon sink in soils. Herein, the chemical properties (using ATR-FTIR) and thermal oxidative stability (using TGA) of biochars derived from these UOW and their three blends were examined. Biochar from SS and AD and the blends were found to possess more ash content, Cl, and alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEM) than that from BP. The conventional recalcitrance index (R50) could not quantify and compare the stability of these mineral- and ash-rich biochars. Hence, a modified thermal oxidative recalcitrance index (TORi) is proposed. All the biochar from blends prepared at highest treatment temperature of 650 °C shows similar aromaticity. However, biochar from blend of 50% SS, 30%BP, and 20% AD exhibits the highest recalcitrance (TORi = 0.193) to become a long-term carbon sink in soil. More than aromaticity, the influence of Si, Fe, and AAEM on the biochar matrix affects its recalcitrance. Variations in the structural properties and recalcitrance of biochars from blends are attributable to the synergy among their constituents SS, AD, and BP. The determined TORi confirms the potential of biochar from the blends of UOW as a long-term carbon sink.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nearly 1.6 billion tonnes (CO2-equivalent) of global greenhouse gas emissions arise from solid waste management [1]. Rapidly increasing amounts of urban organic wastes (UOW) exert growing pressure on solid waste treatment (SWT) systems in emerging economies. Fibrous organic wastes (FOW) from vegetables and fruits, sewage sludge from wastewater treatment plants (WWTP), and anaerobic digestate from food waste treatment constitute a major proportion of these UOW. The urban areas of such emerging countries in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are also hotspots of industrialization and economic growth. These regions are expected to see a doubling of their solid waste generation by 2050. A combined treatment of UOW and its uptake as resources, besides volume reduction, can unlock an economic, sustainable, and eco-friendly SWT approach. Considering their high projected growth rate and the coupled environmental pollution, such sustainable combined treatment options become an existential need in their waste processing infrastructure [2]. Moreover, soil in these countries is getting degraded [3].

Slow pyrolysis is a thermochemical process that devolatilizes biomass and converts them into a carbonized product. If this carbonized product has < 0.7 H/C and < 0.4 O/C, they are considered “biochar.” This recalcitrant aromatic carbon in biochar becomes a stable long-term sink for atmospheric CO2 [4]. The thermal oxidative stability of this recalcitrant carbon in the soil system depends on the pyrolysis temperature and type of input feedstocks. The thermally recalcitrant pyrogenic material is also proven to be resistant to abiotic and microbial degradation [5], resulting in longer stability as carbon sink in soils. Being also porous and nutrient-enriched, biochar has further applications in agriculture, catalysis, water treatment, fuel cells, and hydrogen storage [6, 7].

FOW like vegetable and fruit market wastes (VFW) have the highest availability and lowest procurement costs among all biomass worldwide. Banana peduncle is the stalk supporting fruits and inflorescence of banana trees. It is also an abundantly available feedstock. Places like the Koyambedu Vegetable Market (Chennai, India) produce about 150 tons/day of VFW, of which peduncle is a major constituent [8]. However, only a handful of studies explored them as a feedstock for producing biochar [9,10,11]—most of them investigate a thermal plasma process, not the conventional slow pyrolysis.

Biochar from sewage sludge can have higher concentrations of potentially toxic elements (i.e., As, Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn) and polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) [12], whose bioaccumulation in plants depends on pyrolysis conditions [13]. Such biochars can also be designed to showcase high sorption potential for organic pollutants [14], neutralize alkaline soils [15], and provide a direct nutrient source for flora [16]. Meanwhile, existing research has also shown that biochar derived from anaerobic digestates has soil remediation attributes and a larger potential for heavy metal sorption (especially lead) in aqueous solutions [17,18,19,20]. Thus, biochar produced from co-pyrolysis of banana peduncle, sewage sludge, and anaerobic digestate can have a prospective for carbon sequestration and soil amelioration while also serving as a cost-effective and less-polluting combined conversion strategy for UOW in developing countries. Yet, to the extent of authors’ knowledge, studies in this direction are lacking.

Biomass pyrolysis and its influence on the ensuing biochar characteristics are widely studied, yet poorly understood [21, 22]. This is because the pyrolysis of biomass consists of parallel interdependent reaction pathways of lignocellulose and amino acids with catalytic effects by minerals [23]. Biochar properties—yield, pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC), stability, oxidative stability in the soils [4, 24, 25], pore volume, etc.—are influenced by feedstock and process variables like heating rate, residence time, particle size, feed rate, and flowrate of purge gas [26, 27]. Infrared (IR) spectroscopy and temperature programmed oxidation (TPO) tests in thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) are among the widely used techniques for biochar assay [28].

Mid-infrared FTIR spectroscopy using attenuated total reflection (ATR) is used to compare biochars produced from different feedstocks and process conditions based on the transitions of their functional groups and aromatization [29, 30]. It is an economic method that enables a quick, qualitative, and/or semiquantitative investigation and comparison of biochars. TPO measures the recalcitrance of biochars during thermal decomposition inside TGA in the presence of oxygen. This provides a key assessment of the environmental recalcitrance of biochar over time during soil amendment and carbon sequestration [31].

This study investigates the biochars from UOW blends in terms of its potential to sequester and become long-term carbon sink in soils. Herein, biochar samples were prepared from banana peduncles, sewage sludge, anaerobic digestate, and their blends. The study aims to (a) investigate and compare the prepared biochars samples in terms of structure, functional groups, and extent of transformation using ATR-FTIR and (b) determine and compare the thermal oxidative recalcitrance of these biochars. The study also proposes a modified approach to quantify the thermal recalcitrance of biochars derived when fibrous biomass is co-pyrolyzed with ash- and mineral-rich UOW biomasses.

2 Materials and method

2.1 Materials

The biomass substrates were collected from the city of Chennai, India. They included banana peduncles (BP) from Koyambedu Veg. Market (13°04′05.2″ N, 80°11′55.5″ E), post-fermentation sewage sludge (SS) from Perungudi WWTP (12°57′23.7″ N, 80°14′02.0″ E), and digestate (AD) from two anaerobic digestion plants that process food and market wastes (13°00′38.1″ N, 80°14′12.4″ E and 13°03′56.8″ N, 80°11′25.1″ E). To ensure representativeness, each substrate (on wet basis) was collected in triplicates during three different days of the week from their respective sources. All samples were then oven-dried (at 105 °C for 24 h). Composite samples of SS and AD were prepared by coning and quartering to ensure representativeness according to German Standard LAGa PN 98. These representative samples were shredded to an average particle size of 0.2 mm with Retsch ZM 200. For BP, a composite representative sample was obtained by shredding (particle size 0.2 mm) the dried peduncles and mixing them.

For UOW blend preparation, a microbalance (Denver Instrument Company AA 2000DS) and handheld vibrational sample mixer (to ensure homogeneity in mixing) were used. Biomass blends with three different ratios of SS:BP:AD were prepared on a dry weight basis. The individual unmixed substrates and the three prepared blends are shown in Table 1. Unblended substrates serve as control group. The blends Ms, Mp, and Md have SS, BP, and AD in the ratio 5:3:2, 2:5:3, and 2:3:5, respectively. The blending ratios are selected based on the following: (a) In two blends, SS is kept constant to check the influence of BP and AD, while in two blends, BP is constant to study the influence of AD and SS; (b) the maximum representative sample size that fits the available 70 μl TGA crucible (sec 2.3) is 10 mg due to varying densities of dried BP, SS, and AD; (c) the upper limit of the three UOW in the blends is kept at 50% in purview of the pilot-scale pyrolysis (capacity of 500 kg/day) research this study is part of. Here, high concentrations, say 80%, of SS and AD can result in biochars with high heavy metal and ash concentration, while high values of BP can reduce the conversion potential of SS and AD feedstock lowering the effectiveness of a combined treatment system for UOW; and (d) blending proportions should be able to highlight the existence of synergy, if any, among the three UOW during pyrolysis. The study does not aim to quantify this synergy and interrelationships.

2.2 Elemental, crude fiber, and proximate analysis

The elemental analysis of SS, BP, and AD was done as per German and European standards. The nutrients in plants—P, Ca, K, Mg, Na, and S; silica; iron; and heavy metals, Pb, Cd, Cr, Ni, Cu, and Zn—were determined following DIN EN ISO 11885 (E 22); 2009-09 of German Institute for Standardization (DIN). Mercury and arsenic were obtained from tests according to DIN EN 1483; 2007-07 and DIN EN ISO 17294-2 (E 29); 2005-02, respectively. Chlorine was measured according to DIN 38405-D 1; 1985–12. The CHNO analysis used DIN 51732; 2014–07. For crude fiber and proximate analysis, lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose were determined following the standard VDLUFA III 6.5 of Association of German Agricultural Research Institutes (VDLUFA); mineral matter was determined using DIN EN 12880-S 2a; 2001–02 and volatile matter through DIN 51720:2001-03. The corresponding values of the substrate blends were calculated on a proportionate basis.

2.3 Biochar preparation

Here, biochars were prepared using a thermogravimetric analyzer (Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC 3+ LF) from (a) individual unmixed biomass substrates (SS, BP, and AD) at the highest treatment temperatures (HTT) of 450 °C and 650 °C and (b) their blends Mp, Ms, and Md at HTT of 650 °C. For this, 10 mg of each sample was subjected to slow pyrolysis in a 70-μl Alumina crucible. After pre-purge with nitrogen (99.99% purity, product code—nitrogen 5.0 from Linde GmbH) at 100 ml/min for 10 min, a linear heating program of 20 °C/min raised the sample temperature to their HTT where it was kept constant for 5 min. During pyrolysis, a nitrogen purge was maintained at 50 ml/min. The pre-purge was repeated before each trial. Duplicate trials were performed for each preparation run.

2.4 ATR-FTIR

The ATR spectra were collected for (a) individual unmixed substrates, (b) biochar derived from unmixed substrates at 450 °C and 650 °C, and (c) biochar from substrate blends prepared at 650 °C. A Thermo Fisher Nicolet is50 spectrometer (KBr beamsplitter) was used to collect spectra in the mid-infrared region between 400 and 4000 cm−1. Each spectral image was collected with a method of 16 scans having a resolution and a gain factor of 8 and 2, respectively. With these settings, the mid-IR profile of polyethylene and polyamide-6 was collected and verified against the literature and Thermo Fisher spectral database. The background was collected before each measurement. Spectral data was collected three times for each sample [32] and averaged. Then, it was baseline corrected (in Omnic Ver.9.7) and analyzed in OriginPro® (ver. 2020).

2.5 Temperature programmed oxidation (TPO)

The TPO tests were performed with the abovementioned TGA. Before these experiments, a standard microbalance calibration procedure was completed using an aluminum reference sample (99.999% purity, product code—ME 51119701 from Mettler Toledo). The biochars obtained from the unmixed substrates and their blends (at HTT 650 °C) were combusted in an oxygen atmosphere to an HTT of 1050 °C at a ramp rate of 10 °C/min. The oxidation was sustained through a synthetic air atmosphere (20% O2 and rest N2, from Linde Gases GmbH) with a flow rate of 70 ml/min. The default cell gas flow (protective gas used to protect the measuring cell from corrosive gases) of the instrument was maintained at 20 ml/min of pure nitrogen. Thus, the net oxygen concentration in the reactor was 15.5%. The HTT of 1050 °C was selected as its maximum safely attainable temperature by the reactor. Duplicate trials for each sample were performed, and the average of the TGA data was taken. The differential thermogravimetry (DTG) curves—rate of mass loss vs sample temperature—for the TPO were calculated in OriginPro® (ver. 2020) with 60-point smoothing. The peaks in DTG were assigned using Savitzky Golay second-order smoothing with a 50-point window.

2.5.1 Recalcitrance index (R50)

In the literature, there are few existing methods for quantifying thermal oxidative stability during a TPO. Among them, the first common approach utilizes the DTG curve parameters—peak, onset, and end-set temperatures. The second approach includes the thermal stability indices developed for studying soil organic fraction. Both approaches, on a fundamental level, revolve around the position of peaks in the TGA thermograms. This becomes the inherent demerit as biochar oxidation does not have well-defined peaks. They depend on the conditions of TPO and, most importantly, the feedstock characteristics.

To overcome this shortcoming, the recalcitrance index (R50) was proposed as a measure of biochar stability [33]. It is an energy-based approach where the energy required for breaking the carbon–carbon bonds during 50% oxidative mass loss in biochar is compared with that of a graphite reference. It utilizes temperature as a measure of the required energy input. It is calculated as:

where T50,b and T50,g are temperatures (in °C) corresponding to 50% mass loss of biochar and graphite in a thermal oxidative environment. T50,b, is obtained from the weight loss data of the TGA. If biochar has more stable aromatic structures, it would possess more C=C aromatic bonds and would need a higher temperature to reach a 50% mass loss. Based on R50, biochars are classified as highly recalcitrant class A (R50 ≥ 0.70), stable class B (0.50 ≤ R50 ≤ 0.70), and easily degradable class C (R50 ≤ 0.50). As we reach higher R50 values in class A, biochar stability in soils would be comparable with that of graphite.

3 Result and discussion

3.1 Proximate, crude fiber, and elemental analysis

The elemental, crude fiber, and ultimate analysis of the unmixed UOW substrates SS, BP, and AD are shown in Table 2. The corresponding values for their blends are shown in Fig. 1. For BP, the concentration of macronutrients (P, K, Ca, Mg), with K being the highest, 6.53 wt.-%, and C, H, O, and S content are similar to the reports elsewhere [9, 10]. However, BP has a relatively low nitrogen content (0.98 wt.-%). This N content originates from proteins/amino acids, which can integrate into the parallel reaction pathways of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin during pyrolysis. A C/N ratio of 49.85 for BP does not make them suitable for direct biological treatment processes. Similarly, most organic fraction of municipal solid wastes in countries like India has unfavorable C/N ratios [34]. Among the three substrates here, BP has the highest holocellulose (cellulose + hemicellulose) content [35] and the lowest amount of ash. Its lignin content (7.7 wt.-%) is near to that of hybrid plantain peduncles [36].

SS and AD are complex heterogeneous substrates with a larger amount of inorganics. Similar to AD, the SS also has a low concentration of holocellulose as it is collected from a post-fermentation process, which mainly degrades the acid detergent fiber, starch, carbohydrates, proteins, etc. Digestion usually leaves behind only the resilient lignin structures and increases mineralization [37]. Figure 2 shows the relation between the atomic H/C vs O/C ratio (Van Krevelen diagram) [38] of the unmixed and mixed substrates before pyrolysis. Except for SS, the unmixed substrates show lower oxygenated functional groups as compared with the conventional biomass [39]. SS also has the lowest fixed carbon among the three substrates. Pyrolysis temperature above 600 °C is required to reduce the high H/C ratio in these unmixed substrates and carbonize them [40].

Mp has the lowest O/C among the blends, and this should lead to more stacked polyaromatic hydrocarbons with fewer cross-links during carbonization of its organic fraction [40]. All blends retain a similar H/C ratio that is representative of the aliphatic -CH content. As seen Fig. 1, lead and silica are most prominent in Ms (with 50 wt.-% SS). Sodium and chlorine concentrations are directly proportional to the amount of AD in the mixture. The three biomass blends have more than 2.5 wt.-% of Ca and K. Total and fixed carbon of all the mixtures are similar but lower than 35 and 9 wt.-%, respectively.

3.2 ATR-FTIR spectra

Figure 3 shows the mid-IR ATR spectra of the individual unmixed substrates—SS, BP, and AD—before pyrolysis. BP has lignocellulosic material as indicated by the phenol and amine vibrations between 3500 and 3000 cm−1 and the C-H symmetric stretching between 3000 and 2800 cm−1 (Fig. 3). The fingerprint region (1800 to 400−1 cm) provides more insights. The peak at 1031 cm−1 represents the stretching vibrations of cellulose and its derivatives [41]. The CH2 wagging vibrations at 1312 cm−1; and the shoulder peak near 1730 cm−1 [42] are strong indications of cellulose and hemicellulose (salt or ester form), respectively. The signal at 1604 cm−1 is assigned to the aromatic skeletal vibration mode of lignin [43] and the C=O vibration of lignin and hemicellulose [44]. Other band assignments include the weak 1371 cm−1 as aliphatic CH3 deformation and 1243 cm−1 as C–O stretching of cellulose and hemicellulose [45], which will disappear in biochars prepared above the cellulose devolatilization temperature. BP is not a woody (lignin-rich) biomass. Hence, specificities like hardwood lignin’s syringyl absorption [46], at 1315 cm−1, or the C–O deformation (1081 cm−1) due to secondary alcohols [47] in softwood lignin are obscured by the majority holocellulose content. The spectral features of BP are in agreement with literature values [11, 48], with the main difference being the peaks in the sub 600 cm−1 region that stems from Si–O bonds in the gravel and sand retained in unwashed BP.

In ATR spectra of both AD and SS, the broad NH and phenol region are visible in the range 3800–3000 cm−1. The aliphatic symmetric C–H stretching (2918 cm−1) is sharper, giving them a higher H/C ratio compared with BP. The ensuing vibration in the region of 2850 cm−1 is assigned as the fermi resonance from the aromatic C=C bond vibration of lignin around 1425 cm−1. There is a stronger relative concentration of lignin in them. The signal near 1631 cm−1 is attributed to amides-I [49, 50] from proteins [51] and the aromatic ring stretching. Peaks between 1540 and 1460 cm−1 represent the stretching associated with the carboxylate groups [37]; short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) are the usual byproducts of fermentation. The peaks at 1417 cm−1 for SS and 1407 cm−1 for AD are phenols [51, 52]. Compared with BP, both have sharper spectral features in the sub 600 cm−1 region because of bending vibrations of inorganics like phosphorous, silica, and chlorine [53, 54]. With the reduction of lignocellulose derivatives in biochars, the definition of these inorganic bands becomes more prominent.

The aromatic substitution and/or ring fusion depends on the available adjacent hydrogen atoms in a ring. The less the adjacent hydrogen atoms, the more the fusion and/or substitution. Here, the assignment of aromatic components are made in two regions: (a) 2800–3100 cm−1 for aromatic C–H stretching [55] and (b) 900–700 cm−1 as follows—single aromatic hydrogen with 3–4 ring condensation/substitutions at 870 ± 20 cm−1; ring with two adjacent hydrogen at 815 ± 20 cm−1; ring with three adjacent hydrogen 790 ± 10 cm−1; and aromatic ring with four adjacent hydrogen at 750 ± 20 cm−1 [56,57,58].

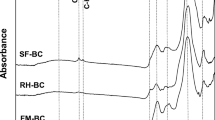

3.2.1 Biochar from the individual unmixed substrates

At 450 °C HTT, the biochar from BP, SS, and AD are labeled 450P, 450S, and 450D, respectively, while the biochars prepared at 650 °C are labeled as 650P, 650S, and 650D. Figure 4 and Fig. 5 show the ATR-FTIR spectra of biochar of unmixed substrates—SS, BP, and AD—prepared at HTT 450 °C and 650 °C, respectively. Comparable trends are observed in their spectral profiles.

At 450 °C

In the spectrum of 450P (Fig. 4), the presence of -OH/-NH groups (3600–3100), aliphatic C–H (3000–2800), and cellulose derivatives (peak near 1026 in the fingerprint region) [59] has reduced. The shift in baseline towards the right denotes increased loss of functional groups and graphitization [60, 61]. Holocellulose content (region around 1031 cm−1) lost most of its spectral features. The other bands are aromatic ring vibrations at 1565 cm−1; C–C stretches in aromatic ring at 1398 cm−1 [60]; CH2 wags of cellulose-hemicellulose remnants at 1308 cm−1 [42]; remaining C–O, C–C, and C–O–H vibrations in polysaccharides at 1034 cm−1 [62]; and substituted aromatic C–H out-of-plane wags between 871 and 756 cm−1 [43, 63, 64]. This biochar still retains aliphatic C. Poly-substituted aromatics have also started forming in 450P.

In the spectra of 450D and 450S, existence of phenols and amides, aliphatic C–H, and cellulose reduces. However, compared with 450P, there is flattening of spectral features between 3600 and 2500 cm−1 at 450 °C due to more prominent loss in functional groups. Carboxylate groups are not visible anymore. As noted by other authors [50, 65], the amide peaks have changed position due to interaction with heavy metals and shifted to lower wavenumbers—shoulder peak near 1600 cm−1. Substituted aromatic signals (near 774 cm−1) have formed in both 450S and 450D. In short, at 450 °C, biochar from BP retains more volatiles than 450D and 450S. The 450D and 450S profiles seem to have an almost complete decomposition of aliphatic C–H bonds, but they retain recalcitrant phenols and lignin. The existence of aliphatic C–H and cellulose derivatives subsides in all biochars at 450 °C, thereby revealing the transformation of biomass with temperature.

At 650 °C

In the IR spectrum of biochar from BP at 650 °C (650P), in Fig. 5, there is an aromatic C–H stretch between 2800 and 3100 cm−1 [55]. The relatively indistinct spectral line in the 4000–2200 cm−1 region confirms a larger loss in aliphatic functional groups (lower O–C and H–C ratio) [61] compared with the spectrum of 450P. The lignin transformational products, ketones (C=O) and phenols (O-H bending), are seen at 1449 and 1359 cm−1, respectively [41]. The stretching of polysaccharides at 1030 cm−1 has considerably reduced. The 870 cm−1 peak is from fused/substituted aromatic rings. The peak at 706 cm−1 is assigned to C–H alkyl bending vibration, showing trace presence of aliphatic volatile structures. The ratio of aromatic compounds (C=C ring stretching at 1650 to 1450 cm−1) to aliphatic compounds (CH stretching at 3000 to 2800 cm−1) [64, 66] is also higher in 650P compared with 450P. The spectral profile of 650P becomes more similar to that of graphite [67, 68], confirming more transformation as compared to 450P.

In the 650D spectrum, due to onset of lignin degradation and higher aromatization, the aromatic skeletal vibration combined with C–H in-plane deformation gets shifted to 1428 cm−1. Silicates and phosphates remain unchanged at temperatures below 700 °C. The wideband around 1000 cm−1 in 650D is from Si–O [16, 53], and phosphates [41]. Aromatic ring substitution is seen at 879 and 776 cm−1 [57, 58]. In 650S spectrum, there is a strong presence of Si–O (1012 cm−1), metal-halogen compounds (sub 600 cm−1) [69], and Si–Ph (1300–1090 cm−1). It undergoes less aromatization as compared with 650P and 650D. Strong peaks between 2280 and 2000 cm−1 are usually assigned to Si–H stretching vibrations [70,71,72] or C ≡ N. But, here, the weak signal in this region is due to the atmospheric background.

A comparison of biochars prepared at 450 °C and 650 °C provides more insights into their composition. The bands at 877 cm−1 (for SS) and 872 cm−1 (for AD) are visible as a sharp peak in their biochars prepared at 450 °C. While they have completely disappeared in 650S, they are only fractionally visible in 650D and shifts to a higher wavelength of 879 cm−1. This represents the changes in their bond energy. In some literature [73], these bands are ascribed to inorganic carbonates. Carbonate decomposition starts above 620 °C and continues till 800 °C. This, as seen here, cannot result in a complete signal loss in its IR spectra in the biochar derived at 650 °C. Carbonates of magnesium have lower thermal degradation temperature. However, Mg has only a trace presence in SS and AD. Here, these bands are assigned as resistant aromatics remaining after anaerobic digestion [45]. In biochar from SS, this band may also arise from oxygen substituted aromatic compounds present in the wastewater [12, 50]. Silicates, phosphates, and iron minerals are thermally stable at higher temperatures. In 450S and 650S, the twin peaks near 428 and 444 cm−1 [74, 75] are from Si–O bending; the peak near 674 cm−1 is Si–O–Si bending [75]. Even in 650S and 650D spectra, the region between 1000 and 1022 cm−1 has a signal due to a combination of thermally stable silicates and phosphates [76]. The 590 cm−1 peak in the IR profiles of 450S and 650S can be from iron oxides [77] or Fe–O–Si bond [78, 79] that forms in presence of iron minerals and silicates at higher temperatures.

The spectral profile of 650P still retains a relatively small signal of volatiles, while 650D and 650S do not. The 650P and 650D have more aromatic ring substitution/fusion, while 650S has the least [12] and retains more Si–O bonds. Compared with biochars at 450 °C, the general pattern is that all the three biochars from unmixed substrates at 650 °C are more stabilized and have more polyaromatic and graphite-like structure. This is comparable with similar multi-HTT pyrolysis results in the literature [15, 16]. Hence, the biochar from biomass blends is investigated at 650 °C.

3.2.2 Biochar from SS, BP, and AD blends

Biochars from pyrolysis (Fig. 6) of blends Mp, Ms, and Md at HTT of 650 °C are labeled as 650Mp, 650Ms, and 650Md, respectively. They have differentiating features mainly in the fingerprint region. Other than the weak peaks between 2200 and 2000 cm−1, the characteristics region is relatively featureless. The broad signal in the region between 1410 and 1425 cm−1 region includes C stretching of heteroaromatic structures [13], OH deformation of recalcitrant phenols [49], and CO32− ions [76, 80]. The lignin transformational products from 650P are not visible in 650Mp due to the catalytic effect of alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEM) incorporated by AD and SS. In 650Ms, absorption by Fe–O bonds of iron oxides is present.

Inorganic spectral signals in the sub 600 cm−1 region persist in these biochars. In the spectra of 650Ms and 650Md, the signals at 438 and 428 cm−1 are from Si–O bending vibration from the silicates in SS, which is also seen in 650S spectra. The concentration of Pb, Zn, Cd, and Cu will be higher in the biochar as they are unaffected during pyrolysis [15]. However, investigation regarding their mobilization is required to understand the bioavailability in soils [13, 81]. The fingerprint region of 650Mp and 650Md features similar contours. It has lost more features as compared with 650P and 650D. More signals are seen for 650Ms in the region 1000–600 cm−1, which are attributed to minerals incorporated from SS. After devolatilization at 650 °C, these biochars are left with amplified concentrations of ash [82] and minerals. This can reduce their higher heating value (HHV) [83] and influence the oxidation mass loss. 650Mp, 650Ms, and 650Md have similar aromaticity. The spectral changes in 650Mp, 650Ms, and 650Md compared with SS, BP, and AD cannot be explained by the proportionate changes of substrates in the blends. Rather, it is evidence of the synergy between SS and AD, and its effects on BP during pyrolysis.

3.3 Biochar stability during TPO

Figure 7 represents the DTG thermograms of the biochars prepared at 650 °C from the individual unmixed substrates, labeled as 650S, 650P, and 650D. And Fig. 8 shows the DTG curves of biochars from blends Ms, Mp, and Md, labeled as 650Ms, 650Mp, and 650Md, respectively.

3.3.1 Biochar from the individual unmixed substrates

During TPO of 650S, 650P, and 650D, four stages are visible: (1) dehydration of physically adsorbed and bound moisture, under 200 °C [37]; (2) oxidation of remaining lignin, substituted aromatics, and polycondensed aromatic structures, 400 to 600 °C; (3) mass loss of carbonates, 600 to 800 °C [84,85,86]; and (4) mainly mass loss due to fixed carbon [87] and residual ash decomposition—heavy metal volatilization and metals reduction—above 800 °C [88, 89].

In DTG of 650P (Fig. 7), there is a small broad peak between 200 and 300 °C. This is the release of remaining volatiles (aliphatic C) left after pyrolysis as seen in its IR profile (sec 3.2.1). In stage 2, reactivity or max peak temperature in their decreasing orders is 650D > 650P > 650S. Despite more aromatization during pyrolysis, reactivity of 650P is lower than 650D due to catalytic effect of K [90] in 650P. Though AD also possesses a higher concentration of AAEM, it also has 7.6 wt.-% of chlorine, which vaporizes a large portion of AAEM as metal chlorides above 500 °C during 650D formation [91, 92]. AD has the highest amount of phosphorus (stable during pyrolysis), which can increase the oxidative stability of 650D [93]. In this stage, 650S has the highest reactivity (lowest max peak temperature—417.11 °C) owing to (a) its comparatively lower aromatic condensation as seen in its IR profile and (b) possible catalytic effect of AAEMs, mainly calcium. During stage 3, 650P has the least mass loss, while 650S and 650D, with higher fixed carbonates, undergoes more oxidation [94, 95].

During stage 4, 650D has the highest rate of mass loss, 650P exhibits a twin peak, and 650S possesses negligible reactivity. Despite similar ash content in SS and AD, the reasons behind inertness of 650S in this region are (a) lowest fixed C in SS (as seen in sec 3.1) and (b) its relatively high silica (SiO2) content that is a major ashing factor during combustion. The AAEM also form silicates in the presence of high amounts of silicate minerals [96]. This ash prevents further diffusion of gases into the biochar at higher temperatures where the reaction is mainly driven by diffusion or mass transfer [97, 98]. Inherited from AD, 650D can retain higher chlorine concentration in it. Heavy metals—Cu, Zn, and Pb—volatilization increases in the presence of chlorine, as reduced metals form metal chlorides that are more volatile than their oxides [88, 99]. Under sub-stoichiometric O2 flow, unburnt C from stage 3 can also get oxidized here.

3.3.2 Biochar from BP, SS, and AD blends

The DTG curves of biochar derived from biomass blends (Fig. 8) also possess four stages as seen earlier. Initially, there is an increase in mass of 650Mp due to surface oxidation. After dehydration, during stage 2, all biochars undergo oxidation of refractory and recalcitrant carbon. 650Mp has the highest reactivity in this stage. 650Ms has the lowest reactivity here due to its high ash and Si concentration, which improves thermal stability owing to the formation of Si-aromatic structure [25, 100] and phosphorus content in Ms. The max peak temperatures during stage 2 lowered from 475.8 °C in 650D to 456.2 °C in 650Md; lowered from 471 °C in 650P to 433 °C in 650Mp; and increased from 417.1 °C in 650S to 463.4 °C in 650Ms. These variations are not proportional to the changes in SS, BP, and AD in substrate blends.

In stage 3, 650Ms and 650Md show similar reactivity due to similar amounts of carbonates. Stage 3 of Mp is spread out over a broader temperature range. During stage 4, (a) the 650Ms has the smallest mass loss like that of 650S, and (b) 650Mp and 650Md have similar mass loss rate and peak temperatures due to similar fixed C.

3.3.3 Thermal oxidative recalcitrance

With an R50 of 0.951, 650P falls in the upper echelons of class A biochar. This is higher than the R50 values of most other biomass-derived biochars prepared at HTT of 650 °C as reported in the literature [101,102,103]. This shows that the stability of 650P is almost like that of graphite with a good amount of condensed/fused aromatic structures. R50 of other biochars is not measurable as they undergo less than 50% mass loss during oxidation. This is due to their higher recalcitrance than graphite.

Similarly, the gained stability index [104], a sub-scale of R50, also cannot be used here. The recently proposed c-based recalcitrance index also suffers the same limitation in addition to the fact that it demands additional equipment for multi-element scanning thermal analysis (MESTA) [105, 106]. These two techniques also isolate the catalytic and/or inhibiting behavior of minerals in the biochar, which plays a major role in total oxidative stability of ash- and mineral-rich biochar. Besides, the value of T50,g depends on the mesh-size of graphite [107], conditions of the oxidative environment—oxygen concentration, sample mass, and heating rate—and intrinsic thermal lag in the TGA equipment. Therefore, T50,g is not a constant that can be used across experiments; it must be measured under each study condition as well—an extra mandatory step. While some authors [108,109,110] have followed this, others [102, 104, 111] have used T50,g value of 886 °C from the original work of [33].

The existing methods cannot quantify and compare the relative changes in overall thermal oxidative stability of biochar from a FOW like BP when it is co-pyrolyzed with multiple ash- and mineral-rich biomasses like SS and AD. In such cases, aromaticity, ashing, mineral types, and phases play equally important roles in oxidation recalcitrance [25]. For such a comparison, suitable reference material is the biochar from unmixed FOW itself.

The thermal oxidative recalcitrance index (TORi) can be defined as the moisture-corrected total mass loss of biochar relative to the temperature at which 50% oxidation of reference material occurs under the same oxidative environment—heating rate, oxygen concentration, and flow rate. It is calculated as

where Δm50, i is the moisture-corrected mass loss of the biochar, i, at the reference temperature Tr (in °C) where 50% mass loss of reference biochars occurs. Equation (3) shows the limiting values: (a) when TORi = +0.5, the biochar i is inert compared with the reference biochar; (b) at TORi = 0, i has the same stability as the reference; and (c) when − 0.5 ≤ TORi < 0, i is more reactive than the reference, undergoing complete oxidation at − 0.5. It can be seen that TORi is based on the R50 concept but only modified to be relativistic. Its values are relative to the biochar whose changes in oxidation stability/reactivity need to be compared during co-pyrolysis of its parent substrate with other mineral-rich biomasses. TORi encompasses the oxidation of volatiles, labile organics, aromatic carbon, and influence of inorganics.

In Table 3, the R50, total oxidative mass loss (moisture-corrected), maximum peak temperatures (during stage 2 of TPO), and TORi of the biochars are shown. Here, 650P is taken as the reference biochar. Its Tr is 842.59 °C. In descending order of stability, TORi of the biochars is 650D (0.294) > 650S (0.278) > 650Ms (0.193) > 650Md (0.142) > 650Mp (0.134) > 650P. The recalcitrance of 650D is the highest among the biochar from unmixed substrates. Despite high recalcitrance, the biochars 650D and 650S can pose difficulties as a carbon sink in soil due to their potentially lower carbon [112] and higher ash and heavy metal content.

While among the biochar from UOW blends, 650Ms has the highest recalcitrance despite lower graphitization compared to 650P as seen in its FTIR spectrum. 650Ms has more silica inherited from Ms (sec 3.1), which increases the recalcitrance through Si encapsulation of carbon [113]. In addition, the higher Fe content in 650Ms (sec 3.2.2) also promotes graphitization [114] and higher recalcitrance [115]. Thus, more than aromaticity, these factors make 650Ms most recalcitrant as a carbon sink in soil. The water extractable organic carbon from 650Ms will also be lowest among the biochar from blends [115]. 650Mp has the lowest TORi despite signals of good aromaticity in its IR spectra. This is due to the catalytic activity of AAEM species during its oxidation reaction [116] and the comparatively lower amount of Si and Fe in it.

Between 650Ms and 650Md, oxidative stability is higher for blend with a higher concentration of SS. While between 650Mp and 650Md, recalcitrance is higher for the blend with higher AD content. The blends 650MS and 650Md, which were prepared from a total of 70% ash and mineral-rich AD and SS, have stabilities far lower than 650D and 650S. These TORi variations of biochar from blends are not proportional to their component concentration, but rather due to synergistic influence of the SS and AD among themselves and on the BP. Non-negative values of TORi of 650Ms, 650Mp, and 650Md indicate that biochars from blends of BP with SS and AD have recalcitrance higher than conventional biomass-derived biochar at HTT of 650 °C. This is due to the interaction of ash and mineral content on the carbon matrix of 650Ms, 650Mp, and 650Md.

4 Conclusion

The biochar from the slow pyrolysis of three biomass, BP, SS, AD, and their blends, Ms, Mp, and Md, were prepared and investigated using ATR-FTIR and temperature programmed oxidation to determine their potential as a long-term carbon sink in soils. Biochars from SS and AD and the blends are richer in AAEM and ash content than that from BP. The conventional R50 index is found insufficient to measure and compare the recalcitrance of such mineral- and ash-rich biochars. A modified thermal oxidative recalcitrance index (TORi) is proposed for this purpose.

For the biochars derived from these three UOW blends at HTT of 650 °C, aromaticity is similar. But, the Si, Fe, and AAEM content influence their recalcitrance more. Biochar gained from UOW blend of 50% SS, 30% BP, and 20% AD exhibits the highest TORi. The relative differences in FTIR spectra and TORi among these biochars are found to be due to the synergy between the constituent SS and AD, and their effect on BP during co-pyrolysis process. The study confirms the potential for biochar derived from the UOW blends of BP, SS, and AD to become stable carbon sink in soils. They possess recalcitrance higher than conventional biochar prepared from biomass at 650 °C. Further investigations are required to quantify the carbon sequestrated per unit weight of these biochars, their PAH content, and bioavailability of heavy metals. The authors recommend future studies in this direction.

Abbreviations

- AAEM:

-

alkali and alkaline earth metals

- AD:

-

anaerobic digestate

- ATR-FTIR:

-

attenuated total reflection-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- BP:

-

banana peduncles

- DIN:

-

Deutsches Institut für Normung (German Institute for Standardization)

- DTG:

-

differential thermogravimetry

- FOW:

-

fibrous organic wastes

- HHV:

-

higher heating value

- HTT:

-

highest treatment temperature

- IR:

-

infrared

- Md :

-

biomass blend prepared from 20%SS, 30%BP, and 50%AD

- Mp :

-

biomass blend prepared from 20%SS, 50%BP, and 30%AD

- Ms :

-

biomass blend prepared from 50%SS, 30%BP, and 20%AD

- PAH:

-

polyaromatic hydrocarbons

- SCFA:

-

short-chain fatty acids

- SS:

-

sewage sludge

- SWT:

-

solid waste treatment

- TGA:

-

thermogravimetry analysis

- TPO:

-

temperature programmed oxidation

- UOW:

-

urban organic wastes

- VFW:

-

vegetable and fruit market wastes

- WWTP:

-

wastewater treatment plant

References

Kaza S, Yao L, Bhada-Tata P, Van Woerden F (2018) What a waste 2.0: a global snapshot of solid waste management to 2050. Urban Development Series. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1329-0

World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420) (2019) (Trans: Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD). United Nations,

Bhattacharyya R, Ghosh B, Mishra P, Mandal B, Rao C, Sarkar D, Das K, Anil K, Lalitha M, Hati K, Franzluebbers A (2015) Soil degradation in India: challenges and potential solutions. Sustainability 7(4):3528–3570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7043528

Lehmann J, Gaunt J, Rondon M (2006) Bio-char sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems – a review. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 11(2):403–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-005-9006-5

Santin C, Doerr SH, Merino A, Bucheli TD, Bryant R, Ascough P, Gao X, Masiello CA (2017) Carbon sequestration potential and physicochemical properties differ between wildfire charcoals and slow-pyrolysis biochars. Sci Rep 7(1):11233. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10455-2

Cha JS, Park SH, Jung S-C, Ryu C, Jeon J-K, Shin M-C, Park Y-K (2016) Production and utilization of biochar: a review. J Ind Eng Chem 40:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2016.06.002

Lehmann J, Rillig MC, Thies J, Masiello CA, Hockaday WC, Crowley D (2011) Biochar effects on soil biota – a review. Soil Biol Biochem 43(9):1812–1836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.04.022

Mozhiarasi V, Speier CJ, Rose PMB, Mondal MM, Pragadeesh S, Weichgrebe D, Srinivasan SV (2019) Variations in generation of vegetable, fruit and flower market waste and effects on biogas production, exergy and energy contents. J Mater Cycles Waste Manage 21(3):713–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-019-00828-2

Karim AA, Kumar M, Mohapatra S, Singh SK, Panda CR (2018) Co-plasma processing of banana peduncle with phosphogypsum waste for production of lesser toxic potassium–sulfur rich biochar. J Mater Cycles Waste Manage 21(1):107–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-018-0769-7

Karim AA, Kumar M, Mohapatra S, Singh SK (2019) Nutrient rich biomass and effluent sludge wastes co-utilization for production of biochar fertilizer through different thermal treatments. J Clean Prod 228:570–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.330

Karim AA, Kumar M, Singh SK, Panda CR, Mishra BK (2017) Potassium enriched biochar production by thermal plasma processing of banana peduncle for soil application. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 123:165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2016.12.009

Waqas M, Khan S, Qing H, Reid BJ, Chao C (2014) The effects of sewage sludge and sewage sludge biochar on PAHs and potentially toxic element bioaccumulation in Cucumis sativa L. Chemosphere 105:53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.11.064

Song XD, Xue XY, Chen DZ, He PJ, Dai XH (2014) Application of biochar from sewage sludge to plant cultivation: influence of pyrolysis temperature and biochar-to-soil ratio on yield and heavy metal accumulation. Chemosphere 109:213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.01.070

Liu XQ, Ding HS, Wang YY, Liu WJ, Jiang H (2016) Pyrolytic temperature dependent and ash catalyzed formation of sludge char with ultra-high adsorption to 1-naphthol. Environ Sci Technol 50(5):2602–2609. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b04536

Hossain MK, Strezov V, Chan KY, Ziolkowski A, Nelson PF (2011) Influence of pyrolysis temperature on production and nutrient properties of wastewater sludge biochar. J Environ Manag 92(1):223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.09.008

Zhang J, Lu F, Zhang H, Shao L, Chen D, He P (2015) Multiscale visualization of the structural and characteristic changes of sewage sludge biochar oriented towards potential agronomic and environmental implication. Sci Rep 5:9406. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09406

Inyang M, Gao B, Pullammanappallil P, Ding W, Zimmerman AR (2010) Biochar from anaerobically digested sugarcane bagasse. Bioresour Technol 101(22):8868–8872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2010.06.088

Inyang M, Gao B, Ding W, Pullammanappallil P, Zimmerman AR, Cao X (2011) Enhanced lead sorption by biochar derived from anaerobically digested sugarcane bagasse. Sep Sci Technol 46(12):1950–1956. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496395.2011.584604

Ho SH, Chen YD, Yang ZK, Nagarajan D, Chang JS, Ren NQ (2017) High-efficiency removal of lead from wastewater by biochar derived from anaerobic digestion sludge. Bioresour Technol 246:142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.08.025

Inyang M, Gao B, Yao Y, Xue Y, Zimmerman AR, Pullammanappallil P, Cao X (2012) Removal of heavy metals from aqueous solution by biochars derived from anaerobically digested biomass. Bioresour Technol 110:50–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.01.072

Song F, Li T, Zhang J, Wang X, Bai Y, Giesy JP, Xing B, Wu F (2019) Novel insights into the kinetics, evolved gases, and mechanisms for biomass (sugar cane residue) pyrolysis. Environ Sci Technol 53(22):13495–13505. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b04595

Özsin G, Pütün AE (2017) Insights into pyrolysis and co-pyrolysis of biomass and polystyrene: thermochemical behaviors, kinetics and evolved gas analysis. Energy Convers Manag 149:675–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.07.059

Kan T, Strezov V, Evans TJ (2016) Lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis: a review of product properties and effects of pyrolysis parameters. Renew Sust Energ Rev 57:1126–1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.185

Sohi S, Lopez-Capel E, Krull E, Bol R (2009) Biochar, climate change and soil: a review to guide future research. Land and water science report, vol 05/09. CSIRO

Han L, Ro KS, Wang Y, Sun K, Sun H, Libra JA, Xing B (2018) Oxidation resistance of biochars as a function of feedstock and pyrolysis condition. Sci Total Environ 616-617:335–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.014

Zhao B, O'Connor D, Zhang J, Peng T, Shen Z, Tsang DCW, Hou D (2018) Effect of pyrolysis temperature, heating rate, and residence time on rapeseed stem derived biochar. J Clean Prod 174:977–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.013

Aysu T, Küçük MM (2014) Biomass pyrolysis in a fixed-bed reactor: effects of pyrolysis parameters on product yields and characterization of products. Energy 64:1002–1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2013.11.053

Amin FR, Huang Y, He Y, Zhang R, Liu G, Chen C (2016) Biochar applications and modern techniques for characterization. Clean Techn Environ Policy 18(5):1457–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-016-1218-8

Chia CH, Gong B, Joseph SD, Marjo CE, Munroe P, Rich AM (2012) Imaging of mineral-enriched biochar by FTIR, Raman and SEM–EDX. Vib Spectrosc 62:248–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vibspec.2012.06.006

Mašek O, Budarin V, Gronnow M, Crombie K, Brownsort P, Fitzpatrick E, Hurst P (2013) Microwave and slow pyrolysis biochar—comparison of physical and functional properties. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 100:41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2012.11.015

Ndirangu SM, Liu Y, Xu K, Song S (2019) Risk evaluation of pyrolyzed biochar from multiple wastes. J Chem 2019:1–28. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4506314

Mukome FN, Zhang X, Silva LC, Six J, Parikh SJ (2013) Use of chemical and physical characteristics to investigate trends in biochar feedstocks. J Agric Food Chem 61(9):2196–2204. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf3049142

Harvey OR, Kuo LJ, Zimmerman AR, Louchouarn P, Amonette JE, Herbert BE (2012) An index-based approach to assessing recalcitrance and soil carbon sequestration potential of engineered black carbons (biochars). Environ Sci Technol 46(3):1415–1421. https://doi.org/10.1021/es2040398

Speier CJ, Nair RR, Mondal MM, Weichgrebe D (2019) Multi-sector evaluation of generation, composition and sustainable treatment systems for commercial waste streams in India. J Mater Cycles Waste Manage 21(5):1155–1166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-019-00869-7

Rahman MM, Islam T, Nayeem J, Jahan M (2014) Variation of chemical and morphological properties of different parts of banana plant (Musa paradisica) and their effects on pulping. Int J Lignocellul Prod 1(2):93–103

Awedem Wobiwo F, Alleluya VK, Emaga TH, Boda M, Fokou E, Gillet S, Deleu M, Gerin PA (2017) Recovery of fibers and biomethane from banana peduncles biomass through anaerobic digestion. Energy Sustain Dev 37:60–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2017.01.005

Zielińska A, Oleszczuk P, Charmas B, Skubiszewska-Zięba J, Pasieczna-Patkowska S (2015) Effect of sewage sludge properties on the biochar characteristic. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 112:201–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2015.01.025

Van Krevelen DW, van Krevelen DW, Schuyer J, van Krevelen DW, van Krevelen DW (1957) Coal science: aspects of coal constitution. Elsevier

Ghassemi H, Shahsavan-Markadeh R (2014) Effects of various operational parameters on biomass gasification process; a modified equilibrium model. Energy Convers Manag 79:18–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2013.12.007

Ishimaru K, Hata T, Bronsveld P, Meier D, Imamura Y (2006) Spectroscopic analysis of carbonization behavior of wood, cellulose and lignin. J Mater Sci 42(1):122–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-006-1042-3

Cantrell KB, Hunt PG, Uchimiya M, Novak JM, Ro KS (2012) Impact of pyrolysis temperature and manure source on physicochemical characteristics of biochar. Bioresour Technol 107:419–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.11.084

Xu F, Wang D (2015) Analysis of lignocellulosic biomass using infrared methodology. In: Pretreatment of Biomass, pp 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-800080-9.00002-5

Faix O (1991) Classification of lignins from different botanical origins by FT-IR spectroscopy. Holzforschung 45(s1):21–27

Chen Z, Hu TQ, Jang HF, Grant E (2015) Modification of xylan in alkaline treated bleached hardwood Kraft pulps as classified by attenuated total-internal-reflection (ATR) FTIR spectroscopy. Carbohydr Polym 127:418–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.03.084

Mulat DG, Dibdiakova J, Horn SJ (2018) Microbial biogas production from hydrolysis lignin: insight into lignin structural changes. Biotechnol Biofuels 11:61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-018-1054-7

Pandey KK (1999) A study of chemical structure of soft and hardwood and wood polymers by FTIR spectroscopy. J Appl Polym Sci 71(12):1969–1975. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19990321)71:12%3C1969::AID-APP6%3E3.0.CO;2-D

Kubo S, Kadla JF (2005) Hydrogen bonding in lignin: a Fourier transform infrared model compound study. Biomacromolecules 6(5):2815–2821. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm050288q

Balajii M, Niju S (2020) Banana peduncle – a green and renewable heterogeneous base catalyst for biodiesel production from Ceiba pentandra oil. Renew Energy 146:2255–2269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.08.062

Coates J (2006) Interpretation of infrared spectra, a practical approach. In: Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry: Applications, Theory and Instrumentation. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470027318.a5606

Jin J, Li Y, Zhang J, Wu S, Cao Y, Liang P, Zhang J, Wong MH, Wang M, Shan S, Christie P (2016) Influence of pyrolysis temperature on properties and environmental safety of heavy metals in biochars derived from municipal sewage sludge. J Hazard Mater 320:417–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.08.050

Provenzano MR, Iannuzzi G, Fabbri C, Senesi N (2011) Qualitative characterization and differentiation of digestates from different biowastes using FTIR and fluorescence spectroscopies. J Environ Prot 02(01):83–89. https://doi.org/10.4236/jep.2011.21009

Provenzano MR, Malerba AD, Pezzolla D, Gigliotti G (2014) Chemical and spectroscopic characterization of organic matter during the anaerobic digestion and successive composting of pig slurry. Waste Manag 34(3):653–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2013.12.001

Snyder RLE (1985) Advances in materials characterization II

Lee M, Kim D-J (2017) Identification of phosphorus forms in sewage sludge ash during acid pre-treatment for phosphorus recovery by chemical fractionation and spectroscopy. J Ind Eng Chem 51:64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2017.02.013

Wiberley SE, Gonzalez RD (1961) Infrared spectra of polynuclear aromatic compounds in the C-H stretching and out-of-plane bending region. Appl Spectrosc 15(6):174–177

Yen TF, Wu WH, Chilingar GV (2010) A study of the structure of petroleum asphaltenes and related substances by infrared spectroscopy. Energy Sources 7(3):203–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00908318408908084

Zhao Y, Feng D, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Sun S (2016) Effect of pyrolysis temperature on char structure and chemical speciation of alkali and alkaline earth metallic species in biochar. Fuel Process Technol 141:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2015.06.029

Budai A, Calucci L, Rasse DP, Strand LT, Pengerud A, Wiedemeier D, Abiven S, Forte C (2017) Effects of pyrolysis conditions on Miscanthus and corncob chars: characterization by IR, solid state NMR and BPCA analysis. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 128:335–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2017.09.017

Xu F, Yu JM, Tesso T, Dowell F, Wang DH (2013) Qualitative and quantitative analysis of lignocellulosic biomass using infrared techniques: a mini-review. Appl Energy 104:801–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.12.019

Liu Y, He Z, Uchimiya M (2015) Comparison of biochar formation from various agricultural by-products using FTIR spectroscopy. Mod Appl Sci 9(4). https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v9n4p246

Keiluweit M, Nico PS, Johnson MG, Kleber M (2009) Dynamic molecular structure of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar). Environ Sci Technol 44:1247–1253

Boeriu CG, Bravo D, Gosselink RJA, van Dam JEG (2004) Characterisation of structure-dependent functional properties of lignin with infrared spectroscopy. Ind Crop Prod 20(2):205–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2004.04.022

Guo Y, Bustin RM (1998) FTIR spectroscopy and reflectance of modern charcoals and fungal decayed woods: implications for studies of inertinite in coals. Int J Coal Geol 37(1–2):29–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-5162(98)00019-6

Van der Marel HW, Beutelspacher H (1976) Atlas of infrared spectroscopy of clay minerals and their admixtures. Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, pp 396

Lu H, Zhang W, Wang S, Zhuang L, Yang Y, Qiu R (2013) Characterization of sewage sludge-derived biochars from different feedstocks and pyrolysis temperatures. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 102:137–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2013.03.004

Bustin RM, Guo Y (1999) Abrupt changes (jumps) in reflectance values and chemical compositions of artificial charcoals and inertinite in coals. Int J Coal Geol 38(3–4):237–260

Mochidzuki K, Soutric F, Tadokoro K, Antal MJ, Tóth M, Zelei B, Várhegyi G (2003) Electrical and physical properties of carbonized charcoals. Ind Eng Chem Res 42(21):5140–5151. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie030358e

Nemanich RJ, Lucovsky G, Solin SA (1977) Infrared active optical vibrations of graphite. Solid State Commun 23(2):117–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-1098(77)90663-9

Fonts I, Azuara M, Gea G, Murillo MB (2009) Study of the pyrolysis liquids obtained from different sewage sludge. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 85(1–2):184–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2008.11.003

Meng XT (1991) The Si-H IR absorption bands in NTD FZ (H2) Si and their identification. Phys B Condens Matter 170(1–4):249–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-4526(91)90132-x

Shi TS, Sahu SN, Oehrlein GS, Hiraki A, Corbett JW (1982) Models for the hydrogen-related defect—impurity complexes and Si—H infrared bands in crystalline silicon. Phys Status Solidi 74(1):329–341

Shi TS, Xie LM, Bai GR, Qi MW (1985) The nature of two intense Si–H IR stretching bands in FZ-Si:H. Phys Status Solidi B 131(2):511–517. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.2221310212

Fu M-M, Mo C-H, Li H, Zhang Y-N, Huang W-X, Wong MH (2019) Comparison of physicochemical properties of biochars and hydrochars produced from food wastes. J Clean Prod 236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117637

Zou J, Dai Y, Wang X, Ren Z, Tian C, Pan K, Li S, Abuobeidah M, Fu H (2013) Structure and adsorption properties of sewage sludge-derived carbon with removal of inorganic impurities and high porosity. Bioresour Technol 142:209–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.04.064

Moradpour R, Taheri-Nassaj E, Parhizkar T, Ghodsian M (2013) The effects of nanoscale expansive agents on the mechanical properties of non-shrink cement-based composites: the influence of nano-MgO addition. Compos Part B 55:193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.06.033

Rajapaksha AU, Vithanage M, Zhang M, Ahmad M, Mohan D, Chang SX, Ok YS (2014) Pyrolysis condition affected sulfamethazine sorption by tea waste biochars. Bioresour Technol 166:303–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.05.029

Gotić M, Musić S (2007) Mössbauer, FT-IR and FE SEM investigation of iron oxides precipitated from FeSO4 solutions. J Mol Struct 834-836:445–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2006.10.059

Bruni S, Cariati F, Casu M, Lai A, Musinu A, Piccaluga G, Solinas S (1999) IR and NMR study of nanoparticle-support interactions in a Fe2O3-SiO2 nanocomposite prepared by a sol-gel method. Nanostruct Mater 11(5):573–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0965-9773(99)00335-9

Predoi D, Crisan O, Jitianu A, Valsangiacom MC, Raileanu M, Crisan M, Zaharescu M (2007) Iron oxide in a silica matrix prepared by the sol–gel method. Thin Solid Films 515(16):6319–6323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2006.11.148

Li Y, Wei Y, Huang S, Liu X, Jin Z, Zhang M, Qu J, Jin Y (2018) Biosorption of Cr(VI) onto Auricularia auricula dreg biochar modified by cationic surfactant: characteristics and mechanism. J Mol Liq 269:824–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2018.08.060

Devi P, Saroha AK (2014) Risk analysis of pyrolyzed biochar made from paper mill effluent treatment plant sludge for bioavailability and eco-toxicity of heavy metals. Bioresour Technol 162:308–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.03.093

Méndez A, Terradillos M, Gascó G (2013) Physicochemical and agronomic properties of biochar from sewage sludge pyrolysed at different temperatures. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 102:124–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2013.03.006

Hung CY, Tsai WT, Chen JW, Lin YQ, Chang YM (2017) Characterization of biochar prepared from biogas digestate. Waste Manag 66:53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.04.034

Leng L, Huang H, Li H, Li J, Zhou W (2019) Biochar stability assessment methods: a review. Sci Total Environ 647:210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.402

Zornoza R, Moreno-Barriga F, Acosta JA, Munoz MA, Faz A (2016) Stability, nutrient availability and hydrophobicity of biochars derived from manure, crop residues, and municipal solid waste for their use as soil amendments. Chemosphere 144:122–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.08.046

Kasozi GN, Nkedi-Kizza P, Harris WG (2009) Varied carbon content of organic matter in Histosols, Spodosols, and Carbonatic soils. Soil Sci Soc Am J 73(4):1313–1318. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2008.0070

Jayaraman K, Kok MV, Gokalp I (2017) Pyrolysis, combustion and gasification studies of different sized coal particles using TGA-MS. Appl Therm Eng 125:1446–1455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.07.128

Zheng G (2000) Thermal events occurring during the combustion of biomass residue. Fuel 79(2):181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-2361(99)00130-1

Deng S, Lu X, Tan H, Wang X, Xiong X (2020) Effects of a combination of biomass addition and atmosphere on combustion characteristics and kinetics of oily sludge. Biomass Convers Biorefin. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-00697-y

Liu Z, Han G (2015) Production of solid fuel biochar from waste biomass by low temperature pyrolysis. Fuel 158:159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2015.05.032

Baxter LL, Miles TR, Miles TR Jr, Jenkins BM, Milne T, Dayton D, Oden LL (1998) The behavior of inorganic material in biomass-fired power boilers: field and laboratory experiences. Fuel Process Technol 54(1–3):47–48

Olsson JG, Jäglid U, Pettersson JB, Hald P (1997) Alkali metal emission during pyrolysis of biomass. Energy Fuel 11(4):779–784

Zhao L, Cao X, Zheng W, Kan Y (2014) Phosphorus-assisted biomass thermal conversion: reducing carbon loss and improving biochar stability. PLoS One 9(12):e115373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115373

Ma B-G, Li X-G, Xu L, Wang K, Wang X-G (2006) Investigation on catalyzed combustion of high ash coal by thermogravimetric analysis. Thermochim Acta 445(1):19–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tca.2006.03.021

Wang C, Zhang X, Liu Y, Che D (2012) Pyrolysis and combustion characteristics of coals in oxyfuel combustion. Appl Energy 97:264–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.02.011

Pohl JH (1986) Influence of mineral matter on the rate of coal char combustion. In: Mineral Matter and Ash in Coal. ACS Symposium Series, vol 301. American Chemical Society, pp 430–436. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-1986-0301.ch030

Shim H-S, Hajaligol MR, Baliga VL (2004) Oxidation behavior of biomass chars: pectin and Populus deltoides. Fuel 83(11–12):1495–1503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2003.11.017

Wang X, Hu Z, Deng S, Wang Y, Tan H (2015) Kinetics investigation on the combustion of biochar in O2/CO2atmosphere. Environ Prog Sustain Energy 34(3):923–932. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep.12063

Yu S, Zhang B, Wei J, Zhang T, Yu Q, Zhang W (2017) Effects of chlorine on the volatilization of heavy metals during the co-combustion of sewage sludge. Waste Manag 62:204–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.02.029

Jindo K, Mizumoto H, Sawada Y, Sanchez-Monedero MA, Sonoki T (2014) Physical and chemical characterization of biochars derived from different agricultural residues. Biogeosciences 11(23):6613–6621. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-6613-2014

Harvey OR, Herbert BE, Kuo LJ, Louchouarn P (2012) Generalized two-dimensional perturbation correlation infrared spectroscopy reveals mechanisms for the development of surface charge and recalcitrance in plant-derived biochars. Environ Sci Technol 46(19):10641–10650. https://doi.org/10.1021/es302971d

Windeatt JH, Ross AB, Williams PT, Forster PM, Nahil MA, Singh S (2014) Characteristics of biochars from crop residues: potential for carbon sequestration and soil amendment. J Environ Manag 146:189–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.08.003

Narzari R, Bordoloi N, Sarma B, Gogoi L, Gogoi N, Borkotoki B, Kataki R (2017) Fabrication of biochars obtained from valorization of biowaste and evaluation of its physicochemical properties. Bioresour Technol 242:324–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.04.050

Gómez N, Rosas JG, Singh S, Ross AB, Sánchez ME, Cara J (2016) Development of a gained stability index for describing biochar stability: relation of high recalcitrance index (R50) with accelerated ageing tests. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 120:37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2016.04.007

Hsieh YP (2007) A novel multielemental scanning thermal analysis (MESTA) method for the identification and characterization of solid substances. J AOAC Int 90(1):54–59

Li S, Chen G (2018) Thermogravimetric, thermochemical, and infrared spectral characterization of feedstocks and biochar derived at different pyrolysis temperatures. Waste Manag 78:198–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.05.048

Jiang W, Nadeau G, Zaghib K, Kinoshita K (2000) Thermal analysis of the oxidation of natural graphite — effect of particle size. Thermochim Acta 351(1–2):85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0040-6031(00)00416-0

Lu J, Yang Y, Liu P, Li Y, Huang F, Zeng L, Liang Y, Li S, Hou B (2020) Iron-montmorillonite treated corn straw biochar: interfacial chemical behavior and stability. Sci Total Environ 708:134773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134773

Yang F, Zhao L, Gao B, Xu X, Cao X (2016) The interfacial behavior between biochar and soil minerals and its effect on biochar stability. Environ Sci Technol 50(5):2264–2271. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b03656

Zhao L, Cao X, Masek O, Zimmerman A (2013) Heterogeneity of biochar properties as a function of feedstock sources and production temperatures. J Hazard Mater 256-257:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.04.015

Cui X, Hao H, He Z, Stoffella PJ, Yang X (2016) Pyrolysis of wetland biomass waste: potential for carbon sequestration and water remediation. J Environ Manag 173:95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.02.049

Agrafioti E, Bouras G, Kalderis D, Diamadopoulos E (2013) Biochar production by sewage sludge pyrolysis. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 101:72–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2013.02.010

Ahmad M, Ahmad M, Usman ARA, Al-Faraj AS, Abduljabbar A, Ok YS, Al-Wabel MI (2019) Date palm waste-derived biochar composites with silica and zeolite: synthesis, characterization and implication for carbon stability and recalcitrant potential. Environ Geochem Health 41(4):1687–1704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-017-9947-0

Xiao X, Chen B, Chen Z, Zhu L, Schnoor JL (2018) Insight into multiple and multilevel structures of biochars and their potential environmental applications: a critical review. Environ Sci Technol 52(9):5027–5047. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b06487

Xiao R, Wang JJ, Gaston LA, Zhou B, Park JH, Li R, Dodla SK, Zhang Z (2018) Biochar produced from mineral salt-impregnated chicken manure: fertility properties and potential for carbon sequestration. Waste Manag 78:802–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.06.047

Dieguez-Alonso A, Funke A, Anca-Couce A, Rombolà A, Ojeda G, Bachmann J, Behrendt F (2018) Towards biochar and hydrochar engineering—influence of process conditions on surface physical and chemical properties, thermal stability, nutrient availability, toxicity and wettability. Energies 11(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/en11030496

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Central Leather Research Institute (CLRI) in Chennai, India, for their onsite support, substrate procurement, and shipment.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was funded by the Indo-German Science & Technology Centre (IGSTC) through the project PYRASOL (No. 60451530) under the 2 + 2 scheme, Ministry of Education and Research Germany (BMBF), and German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Any financial, personal, and/or other relationships with people, organizations, or entities that could be perceived to influence this submitted work have been duly disclosed and acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nair, R.R., Mondal, M.M. & Weichgrebe, D. Biochar from co-pyrolysis of urban organic wastes—investigation of carbon sink potential using ATR-FTIR and TGA. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 12, 4729–4743 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-01000-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-01000-9