Abstract

While the COVID-19 pandemic brought with it multiple challenges for families and the Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) workforce, it also highlighted the essential role of ECEC in the lives of children and families and presented unique opportunities for innovation and learning. The current study sought to explore learnings from this uniquely challenging period, including the factors and strategies that best supported educator wellbeing and family engagement in ECEC settings, from the perspectives of families, centre directors and educators. In 2021, 104 Centre Directors/Educators and 102 families completed online surveys exploring wellbeing and educator–family relationships. Correlations suggest that robust professional wellbeing and resilience are potential enabling factors for strong family engagement, and that supportive organisational structures in ECEC settings are a protective factor for both educator wellbeing and family engagement. In addition, five effective family engagement strategies were derived from the qualitative data: (1) drawing on personal and professional knowledges to enrich children’s learning at home; (2) prioritising regular and reliable communication with families; (3) maintaining familiar relationships and a sense of community; (4) providing person-centred support and a bridge to other services; and (5) nurturing mutually supportive educator–family relationships. Learnings provide important insights that may inform ongoing quality improvements across different ECEC contexts, and to help safeguard against the negative impacts of future global crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In many countries, the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have heightened the need for effective early intervention for children and families, especially for those living in disadvantaged circumstances (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2022). One way to achieve this is through sustained participation in high quality early childhood education and care (ECEC) programs and the nurturing of strong educator–family partnerships (Barnett et al., 2020; Pascoe & Brennan, 2017). These partnerships are contingent on early childhood educators having the emotional capacity to effectively engage with children and families (McWayne et al., 2022). Educators are key to lifting the quality of early learning programs through responsive educator–child interactions (Burchinal et al., 2018) and the fostering of supportive educator–family relationships that build trust and collaboration (Australian Government Department of Education [AGDE], 2022; Jeon et al., 2020). Positive educator–family partnerships can support the mutual sharing of important information about children’s early learning, promote socially and culturally inclusive practice, enhance the continuity of children’s learning and the quality of home learning environments, and facilitate family engagement with other support services (Barnett et al., 2020; Jeon et al., 2020; Niklas et al., 2016; McWayne et al., 2022; Purola & Kuusisto, 2021). As such, the value of family engagement with early childhood services lies not only in child participation (and the ensuing child learning and development outcomes), but also in the ways services can support families and communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the associated lockdown measures presented unprecedented challenges for many children and families, including reduced or restricted face-to-face contact with ECEC services (Brown et al., 2020; Evans et al., 2020). Of particular concern, research suggests that families experiencing vulnerabilities were more likely to be adversely affected by lockdown measures, with financial stressors, social isolation and limited access to support services adding strain to parent–child relationships (Morgul et al., 2022; Prime et al., 2020). Research has also highlighted the significant emotional toll borne by early childhood educators during the pandemic, many of whom were required to navigate rapid changes to policy, funding, and working conditions—while experiencing their own personal stressors and uncertainty about their future employment (Berger et al., 2022; McFarland et al., 2022).

Although the pandemic brought with it multiple challenges for families and the ECEC sector, it also highlighted the critical role of ECEC in the lives of children and families and presented unique opportunities for innovation and learning. The current study explores the perspectives and experiences of Centre Directors, educators, and families attending Australian ECEC services, to understand how educator wellbeing and family engagement—key levers of ECEC program quality—were supported and sustained during this uniquely challenging period. Learnings can provide important insights to inform ongoing quality improvements across different ECEC contexts, and to help safeguard against future global crises.

ECEC in Australia

In Australia, ECEC is defined as non-compulsory education and care for children who are preschool aged or under (i.e., children from birth to 5 years and through their transition to school) (AGDE, 2022). There are three main types of centre-based ECEC services in most states and territories: long day care, whereby for-profit or not-for-profit organisations provide full-day care and education throughout the year to children below school age; and preschools and kindergartens, which provide early childhood education for children in the year or two before they commence full-time schooling. These services must meet minimum educator qualification requirements for working with children preschool age and under in centre-based services, as set out in the National Quality Framework (NQF) (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority [ACECQA], 2017). In addition, these services are required to practice according to principles and learning outcomes established by an approved learning framework; Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (EYLF), version 2 (2022) and the National Quality Standard, (NQS) which includes seven quality areas against which services are assessed and rated (ACECQA, 2017). ‘Collaborative partnerships with families’ is one of the key quality areas in the NQS, as well as a key principle in the EYLF, with the framework stating that ‘learning outcomes are most likely to be achieved when early childhood educators work in partnership with families’ (p. 13).

Despite growing recognition of the potential benefits of quality ECEC that fosters strong-educator family partnerships, the mixed-market delivery model in Australia means there are variations in both the accessibility and quality of ECEC services serving all families (Gilley et al., 2015). Evidence indicates that, while children with additional risk factors or living in areas of greater socio-economic disadvantage stand to benefit the most from participation in high quality ECEC (Burchinal et al., 2018; de Souza Morais et al., 2021; Goldfeld et al., 2016), they are less likely to access high quality programs (Gilley et al., 2015; Pascoe & Brennan, 2017). This problem has been exacerbated by the social and economic impacts of the pandemic which has served to widen the gap between children from low- and middle-class families (O’Connor et al., 2022). In addition, high levels of emotional exhaustion and burnout in the Australian ECEC workforce were well documented prior to the pandemic (Thorpe et al., 2020) and arguably intensified during this period (Eadie et al., 2021). Poor educator wellbeing can lead to high levels of turnover, disrupting both the quality of practice and continuity of educator–family relationships (Thorpe et al., 2020). As such, efforts to support family engagement in ECEC must also account for educator wellbeing, especially in the post-pandemic context (Hine et al., 2022; Jackson, 2020).

The current study

This study aimed to explore the enablers for strong educator wellbeing and family engagement within the unique context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on prior research, we hypothesised that supportive organisational structures (i.e., supportive leadership, cooperative relationships with co-workers, flexible working environments) (Eadie et al., 2021) would be enablers for strong educator wellbeing and family engagement, particularly within the challenging setting of the pandemic. In addition, the study aimed to explore innovative and effective strategies adopted by educators during this period to maintain their connections with families, despite the changes to working conditions and restrictions to face-to-face contact. The specific research questions were:

From the perspectives of Centre Directors, educators and families:

-

(1)

To what extent were educator wellbeing, resilience and relationships impacted during the pandemic?

-

(2)

What were the enabling factors for strong educator wellbeing and family engagement during the pandemic?

-

(3)

What are the learnings to carry forward in relation to effective family engagement strategies implemented during the pandemic?

Theoretical framework

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) is well suited to help us understand the multiple influences simultaneously impacting educators’ wellbeing and their capacity to effectively build relationships with families. This theoretical approach recognises that an individual’s wellbeing is significantly influenced by a complex and interactive system of relationships in their immediate and wider environment, from the home and ECEC setting, to broader socio-cultural contexts. Within this system, it is the microsystem, which includes the immediate environmental surrounds of an individual and the proximal processes within it, that is the most influential. In this way, educators both influence and are influenced by proximal processes within their immediate environment (or microsystem). As key actors within an educator’s microsystem, children and families are involved directly in proximal processes as they engage in interactions. In this way, an educator’s wellbeing is influenced by both their personal characteristics and the reciprocal interactions they have with children, families, and co-workers (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). In these interrelated contexts, educators may encounter supports for wellbeing (e.g., supportive leadership) that in turn supports the nurturing of positive relationships with families, but also risk factors (e.g., reduced face-to-face contact with children because of the pandemic) that may negatively impact their wellbeing and relationships. To identify the enablers for strong educator wellbeing and family engagement, it is important to consider the significance of both personal and contextual factors in the experiences of educators. Understanding how educators responded to some of the unique challenges presented during the pandemic and the factors that best supported educator wellbeing and family engagement (and the relationship between these factors) can provide important lessons for future practice.

Methods

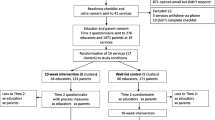

The current study is nested within a larger mixed-methods study focusing on family engagement and educator wellbeing in ECEC settings during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022). The research team represented expertise in child development and ECEC research, as well as family and community health and wellbeing experts. The overall methodology included the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data, and educational research methods (surveys and interviews) as well as participatory action research. The research design and interpretation of data were informed by a social constructivist paradigm, in that the study sought to explore knowledges and meanings that are co-created through interactions with others (Armstrong, 2019). The current paper reports on findings from the online survey component of the broader study. Ethics approval was received from the relevant institution prior to the study commencing.

Recruitment and data collection

A cross-sectional survey design was employed. Survey items were designed to elicit insights about the challenges and enablers for educator wellbeing and family engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic, from the perspectives of Centre Directors, educators and families. An online survey was used due to restrictions on social contact imposed during COVID-19, and to facilitate input from informants across Australia with minimal intrusion. A convenience sample that utilised snowball sampling methods was used to recruit Centre Directors through the head office of a large early learning provider (a partner on this project) in April 2021 via a link to an online survey. This early learning provider is a not-for-profit provider of ECEC services in Australia, including long day care, preschool and kindergarten programs. Centre Directors who had consented to participate invited educators and families at their services to take part in online surveys via email and online newsletters. Prior to completing the survey, all participants were provided with information about the study. Participation was voluntary and all participants provided informed consent online prior to completing the surveys.

Measures

Educator survey

The educator survey comprised five components: (1) demographic questions designed by the research team (e.g., role, years of experience, highest qualification); (2) study-designed questions which asked educators to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale to what extent the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their wellbeing and relationships with children, families and co-workers; (3) study-designed open-text questions about challenges and supports for family engagement and educator wellbeing during the pandemic (e.g. ‘Did you experience any specific successes to your family engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic?’); (4) study-designed family engagement scale which asked educators to rate their levels of agreement with statements relating to their confidence and beliefs about family engagement on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g,. ‘I feel confident in my ability to build effective relationships with the families of the children at this centre’); and (5) the Early Childhood Professional Wellbeing (ECPW) scale (McMullen, et al., 2020) and the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) (Smith et al., 2008).

The study-designed family engagement scale was included in the Educator, Centre Director and Family surveys (with wording adapted to capture different participant perspectives). Items were derived from the National Quality Framework (ACECQA, 2018) and aligned with Quality Area 6: Collaborative partnerships with families and communities. This scale was used to ensure relevance for the Australian cohort, and to generate information about specific indicators of family engagement that align with established benchmarks of quality in Australian ECEC settings. All respondent groups were asked to rate their levels of agreement with a series of statements on a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 = Strong disagree and 5 = Strongly agree). Items included in the Educator and Centre Director survey included questions about challenges and supports in relation to family engagement, and educators’ knowledge and confidence in building relationships with families, e.g. ‘I feel confident in my ability to build effective relationships with the families of the children at this centre’. Items in the family survey asked about family satisfaction with the communication and support provided by their ECEC service, and their relationships with educators, e.g., ‘I have a good relationship with the educators that care for my child’. Internal reliability was tested for each of the family engagement scales. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.922 for the four items in the educator survey, 0.974 for the 21 items in the Centre Director Survey, and 0.876 for the for the five items in the family survey. This suggests that items in the family engagement scales have relatively high internal consistency. Further, factor analysis revealed a one factor solution, suggesting that all of the items fit onto a single theoretical construct for each of the family engagement scales (with the first factor accounting for 81.35% of the total variance in the educator survey, 67.65% for the Centre Director survey, and 67% for the family survey).

The ECPW is a validated scale that was designed to measure EC educators’ wellbeing and risk of turnover (see McMullen et al., 2020). The framework is underpinned by sociocultural theory, with wellbeing based on nine ‘senses’ that capture Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. ECPW items load onto three factors: Collegial Relationships (e.g. ‘I feel I belong to a community in my early learning setting’), Supportive Structures (e.g., ‘The emotional climate in my early learning setting puts me at ease’), and Professional Beliefs and Values (e.g., ‘I feel free to practice according to my professional beliefs’). An overall score is calculated by adding the 27 wellbeing items (rated on a 5-point Likert scale), with higher scores indicating higher professional wellbeing. Risk of turnover is calculated as the total of three turnover items (e.g., ‘I feel satisfied with my position as an early childhood professional’), ranging from 3 to a maximum of 15, with higher scores indicating lower risk of turnover.

The Brief Resilience Scale is the most concise of the commonly used scales to measure resilience. It has good criterion validity and is used to assess an individual’s perceived ability to bounce back or recover from stress (Smith et al., 2008). The scale was developed to assess a unitary construct of resilience, including both positively and negatively worded items. The total score on the BRS is reached by adding the responses from 1 (low resilience) to 5 (high resilience) for six items, giving a range from 6 to 30.

Centre director survey

The Centre Director survey comprised four components: (1) demographic questions designed by the research team (e.g., years of experience, highest qualification, working hours); (2) study-designed questions about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Director’s relationships with children, families and their team; (3) a study-designed family engagement scale (see above) and (4) open-text items about barriers and supports for family engagement during the pandemic.

Family survey

The family survey comprised four components: (1) demographic questions designed by the research team (e.g., child age, languages spoken at home, hours attending ECEC in person); (2) a study-designed family engagement scale (see above); (3) multiple choice items about communication practices used by ECEC services during the pandemic; and (4) open-text items about barriers and supports for family engagement during the pandemic.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted in two stages. In stage 1, descriptive statistics were used to illustrate educators’ professional wellbeing and resilience scores, and the impact of the pandemic on educator wellbeing and educator–family relationships (addressing RQ1). We then examined correlations between educator characteristics (e.g., role, years of experience) and structural characteristics of the services where they worked (e.g. service size, socioeconomic location of service) and educator wellbeing and resilience scores (addressing RQ2). Cronbach's alpha was then used to determine the internal reliability of each of the study-generated family engagement scales, and correlations were calculated to examine the potential relationship between professional wellbeing and resilience and family engagement scores (also addressing RQ2). Tests for skewness and kurtosis indicated relatively normal distribution of the ECPW and BRS data. However, the family engagement data (as reported by educators, Centre Directors and families) were skewed and therefore Spearman correlations were used for correlational analyses with these data.

In Stage 2, thematic analysis of the open text survey responses in relation to effective family engagement practices was conducted (addressing RQ3). A reflexive thematic approach (Braun & Clarke, 2019) was used to analyse the qualitative data from the three surveys (Centre Director, educator and family responses). The approach was inductive (not hypothesis driven), semantic (focused on what respondents were reporting rather than determining the assumptions underpinning their responses) and critical realist (focused on reporting meanings and the lived experiences of participants). The analytic process was exploratory, flexible, and recursive in nature, involving familiarisation with the raw data in each set of survey responses, coding important features of the data in relation to the research questions, looking for patterns of meaning within and across the survey responses, generating overarching themes, reviewing and refining the themes, and, finally, defining and describing each theme.

Results

Participant characteristics

Online surveys were completed or partially completed by 104 Centre Directors/Educators and 102 parents/caregivers attending 38 ECEC services. Eleven educator respondents (17% of those who were responding to the educator facing survey) were working in dual Educator/Assistant/Centre Director roles; hence the number of respondents in this role (49) is greater than the total number of services (38). Of the 104 educator and Centre Director participants, around half had over 11 years’ experience working in ECEC, and the majority (80%) were working full-time, while 19% were working part-time and 1% on a casual basis. Around a quarter held a Bachelor (27%) or Masters (2%) qualification, 61% held a Diploma, and 10% a Certificate. Participating ECEC services were varying sizes, located across six states, and rated as ‘meeting’ (63%) or ‘exceeding’ (37%) the national Quality Standard. Services were distributed across SEIFA (Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas) quintiles (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021) with 29% in quintiles 1–2, 21% in in the middle quintile, and 50% in quintiles 4–5 (most advantaged). Of the 102 families attending the aforementioned services, 91% were mothers, 75% were degree qualified, and most were located in Victoria (32%), New South Wales (30%) or Queensland (27%). Participant and service characteristics are provided in the supplementary material.

RQ1. Impact of the pandemic on educator wellbeing and relationships

Table 1 shows that just under a third (31%) of educators reported the pandemic had a negative impact on their general wellbeing. However, close to half of educator and Centre Director respondents reported a positive impact on their relationships with children (49%), co-workers (47%) and families (54%).

Table 2 sets out the self-reports of educators on professional wellbeing items (ECPW scale) and resilience items (BRS scale). Means and standard deviations are presented for the average overall professional wellbeing score, the three factor scores and the risk of turnover score. Of the three factors of wellbeing, average scores for Professional Beliefs and Values were highest (4.08), while average scores for Supportive Structures were the lowest (3.71). Means and standard deviations are also present for the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS). The average BRS score was in the normal range for resilience (3–4.30), with 45 educators (70%) reporting scores in this range, 13 educators (20%) reporting scores in the low range (1–2.99), and 6 educators (9%) reporting scores in the high range (4.31–5).

RQ2. Enabling factors for strong educator wellbeing and family engagement

In the first instance, we examined associations between educator characteristics (work role, years of ECEC experience, highest qualification in ECEC, working hours, contact hours with children, age of children) and professional wellbeing and resilience scores. A small association was found between work role and wellbeing (ECPW), (r(64) = 0.28, p < 0.05), and between work role and resilience (BRS), (r(64) = 0.41, p < 0.01), suggesting that those working in more senior roles (e.g. Centre Directors) were slightly more likely to have stronger professional wellbeing and resilience scores. Stronger levels of resilience were also associated with higher levels of professional wellbeing (r(64) = 0.42, p < 0.01). No significant correlations were found for the other participant characteristics or between structural characteristics of services (size, location, national quality rating, SEIFA quintile) and wellbeing or resilience scores. Correlations are provided in the supplementary material.

A small but significant association was also found between ECPW scores and educators’ self-reports of the impact of the pandemic on their general wellbeing (r(64) = 0.27, p < 0.05), and their relationships with co-workers (r(64) = 0.30, p < 0.05), suggesting that stronger professional wellbeing acted as a buffer against the negative impacts of the pandemic. Of the three ECPW factors, supportive structures was the most protective against the negative impact of the pandemic on both educators’ general wellbeing (r(64) = 0.40, p < 0.01), and their relationships with co-workers (r(64) = 0.43, p < 0.01). No significant correlations were found between the other ECPW factors and the impact of the pandemic on wellbeing or relationships.

In relation to family engagement, no significant correlations were found between structural characteristics of services (size, location, national quality rating, SEIFA quintile) and average scores for family engagement, as reported by Centre Directors, families and educators. However, there was alignment of relatively high scores across most family engagement indicators in all three surveys. Findings from the educator survey indicate that most educators reported having the confidence and skills to build effective relationships with families and to provide appropriate communication and support for children’s learning progress. Further, findings from the Centre Director survey indicate that most Centre Directors believed their service was responsive to families. Family engagement scores derived from Educator and Centre Director reports are provided in Table 3.

In addition, correlational analyses indicated that higher family engagement scores were associated with stronger professional wellbeing (as reported by educators) (r(59) = 0.39, p < 0.01). Of the three ECPW factors, Supportive Structures was most strongly associated with family engagement scores (r(59) = 0.42, p < 0.01), followed by Professional Values and Beliefs (r(59) = 0.38, p < 0.01), and Collegial Relationships, (r(59) = 0.28, p < 0.01). In addition, higher resilience had a small but significant association with stronger educator reports of family engagement (r(59) = 0.28, p < 0.01).

RQ3. Effective family engagement strategies

Findings from the family survey reports show that most parent/caregiver respondents (> 90%) were satisfied with the support provided by the service and felt that they and their children had good relationships with the educators at their service. However, slightly fewer respondents (71%) agreed that they were satisfied with the support their child received during the pandemic, and by the overall support provided by their ECEC service during the pandemic (64%). Of the 19 family respondents who expressed dissatisfaction with their service’s support provided during the pandemic, approximately half were located in Victoria, where the most severe COVID-19 restrictions were in place.

Qualitative analyses of the open text survey responses provided by educators, Centre Directors and families highlighted the following effective strategies for supporting family engagement.

-

1.

Drawing on personal and professional knowledges to enrich children’s learning at home

Educators indicated that working in partnership with parents during stay-at-home orders provided opportunities for parents to contribute more directly to children’s learning experiences by drawing on their personal and/or professional skills: ‘We were able to support our dinosaur topic of 2020 with a zoom call to a real palaeontologist as parents were so engaged with our day-to-day learning’ (Ed34). Likewise, educators and Centre Directors supported parents in the provision of rich learning experiences at home by contributing their own personal or professional knowledges; ‘the centre offered Spanish sessions that were really well received (parents and children were dancing). Also offered cooking sessions for families’ (Ed4); and ‘we were able to maintain connections with families through video calls which involved parents doing a science experiment with the children’ (C35). These contributions to children’s learning were appreciated by families: ‘often they would do story readings that we could watch at home’ (F30) and ‘[we] appreciated the extra effort that [service] went to to ensure everyone still had access to the educators/some form of learning’ (F55).

-

2.

Prioritising regular and reliable communication with families

Educators and Centre Directors recognised the importance of providing regular updates for families during this period of uncertainty: ‘parents loved the constant updates that we posted to keep them informed and up to date’; (Ed32) and ‘predictable, proactive and responsive communication to families as a group and to individuals was needed to ensure families were well informed, reassured and supported’ (C18). Correspondingly, family respondents also expressed their appreciation for regular and easily accessible communication from their ECEC services: ‘I felt like I was being well communicated with and had all the information and support I needed’; (F15) and ‘the centre staff used Story Park very regularly to provide almost daily updates which were very much appreciated’ (F15).

-

3.

Maintaining familiar relationships and a sense of community

Educators and Centre Directors recognised the importance of maintaining established relationships with children and families, ‘Zoom sessions with children and families really supported the connection and continuity of relationship for families and children with the educators and the centre as a whole’ (C21); ‘We were able to support families throughout the period of uncertainty with consistency of practice and familiar interactions (C17).’ This extended to building and maintaining a sense of community for children and families who were unable to attend services in person: ‘It’s about valuing relationships and our community’ (Ed42); and ‘ANZAC Day veterans doing Zoom call with children…we got involved with the local hospital sending baskets of goodies to our front liners every week’ (C35). For families who continued to attend services, Centre Directors noted the importance of maintaining a sense of normality; ‘families who continued to attend commented on the calm environment…families commented that this was the only “normal” place other than home, that the children got to go to’ (C18). These efforts were valued by families; ‘we did appreciate that we could call in and see the educators and engage when we could’ (F10); and ‘we communicated with my daughter’s key educator during the period of leave…This was important’ (F20).

-

4.

Providing person-centred supports and a bridge to other services

Centre Directors and educators endeavoured to respond to individual families’ needs during the pandemic using mixed methods to reach different families; ‘Families were engaged in surveys to ensure we were meeting their needs’; (C29) and ‘our [educators] reimagined how they could reach their families. They dedicated providing programs on certain days of the weeks for families, pre-recorded songs and story times’ (C29). As noted by Centre Directors, taking a flexible approach was important to ensure services were meeting the varying communication preferences of families; ‘really thinking about our families and meeting their needs’ (C18); ‘we found the most useful strategy for vulnerable children was a phone call, we would call to check in often and offer support’ (Ed34); and ‘we also provide flexibility to accommodate change of attendances and payment plans to better support family needs’ (C25). This included the provision of video messages in different languages; ‘videos of educators reading stories, singing in different languages and sending these videos to families’ (C35); facilitating connections with other services such as psychologists and health programs; ‘We provided contacts for local health and support services’ (Ed37); and ‘we provided Zoom online meetings with our resident psychologist to support wellbeing and practices during the height of the pandemic’ (Ed34). In addition, Centre Directors reflected on the importance of providing technical support and support in applying for financial payments: ‘Technical support with Centrelink applications and permits for families’’ (C21) and ‘we supported families to access government supports like Temporary Financial Hardship Payments’ (C6).

-

5.

Nurturing mutually supportive educator–family relationships

Centre Directors and educators described providing responsive supports for child and family wellbeing: ‘Being supportive and responsive through holistic approaches’ (Ed29); and ‘just being able to listen and empathise with the families regarding their personal experiences’ (Ed60). In some cases, this resulted in strengthened relationships between educators and families; ‘during this time of uncertainty we really strived to support, mentor and just be present for our families’ (C28); ‘our relationships with our families and children grew really strong and we developed a deeper connection with each family;’ and ‘families seemed closer with educators’ (C21). These responsive approaches were appreciated by families: ‘[educators] were always happy to discuss issues’ (F60) and ‘they were accessible and available on phone and…also in person at the centre itself whenever needed’ (F137). Likewise, educators reflected on how families demonstrated an increased gratitude for their work during this period; ‘Our families stood by us and spread positive stories’ (Ed37) and ‘I was showed more trust and thankfulness during this period’ (Ed60). For some educators, this expressed gratitude from families appeared to bolster their own job satisfaction and sense of wellbeing: ‘families were appreciative of our services’ (Ed67) and ‘appreciation goes a long way’ (Ed48).

Discussion

This study used a mixed methods online survey approach to explore the enablers for strong family engagement and educator wellbeing, from an ecological perspective. The sample captured the perspectives of Centre Directors, educators and families attending ECEC services across Australia. Viewed from Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological lens, educators in this study responded to the challenges of the pandemic with agility, ensuring that their relationships with children and families within their immediate environment (or mesosystem) were largely maintained despite the negative impacts of the pandemic (in their macro-system) disrupting the working conditions within their mesosystem, with potential ramifications for their own general wellbeing (in their microsystem).

In terms of the impact of the pandemic, just under a third of educators reported the pandemic had negatively impacted their general wellbeing. While this is a significant percentage, it is measurably lower than the 85.9% of educators who reported a negative impact to their wellbeing in research conducted with a Victorian sample during the height of the pandemic in 2020 (Eadie et al., 2021). It is possible that this discrepancy reflects the difference in the timing of data collection as well as the difference in sample locations, as the Victorian cohort in the cited study experienced strict lockdowns and complex working conditions during the pandemic. Interestingly, close to half of respondents reported the pandemic had positively impacted their relationships with children and more than half of participants reported a positive impact on their relationships with families. This mirrors prior research conducted during the pandemic (Eadie et al., 2021) and suggests that educators felt they were able to sustain strong relationships with children and families despite the perceived negative impacts of the pandemic to their own wellbeing. This is corroborated by the family survey findings, where most parent/caregiver respondents agreed that they were satisfied with the support provided by their service during the pandemic. Of the minority of family respondents who expressed dissatisfaction with their service’s communication and support provided during the pandemic, half were located in the state of Victoria, where there were particularly long periods of pandemic-imposed restrictions.

Average scores for professional wellbeing and resilience (as measured on the ECPW and BRS scale) were in the normal range for the participants in this study (despite the reported negative impacts to their general wellbeing). The average score for professional wellbeing was comparable to ECPW scores reported by Eadie et al. (2021) and McMullen et al. (2020). Stronger professional wellbeing—and in particular, Supportive Structures—were inversely associated with the reported impact of the pandemic on educators’ relationships with co-workers and their general wellbeing, suggesting that these factors may have provided a protective buffer against the negative impact of the pandemic. In addition, Supportive Structures was most significantly associated with family engagement scores. According to McMullen et al. (2020), the indicators in the Supportive Structures factor align with aspects of the physical environment, government regulations, service policies and practices, and the emotional climate (e.g., supportive leadership, collegial relationships, job security). Notably however, there were no significant correlations between the structural service characteristics (e.g., size, SEIFA rating) and family engagement (as reported by educators, Centre Directors and families). This suggests that regardless of the service size or location, a supportive organisational climate is important for maintaining both strong educator wellbeing and family engagement. This finding aligns with prior research highlighting the importance of supportive organisational structures to foster healthy educator wellbeing (Eadie et al., 2021; Hine et al., 2022). Although only small associations were found between educator role and resilience or wellbeing, these findings align with previous research suggesting that educators in more junior roles may experience poorer wellbeing or resilience due to lower pay, inferior professional recognition, or job insecurity (Eadie et al., 2021; Logan et al., 2020; McMullen et al., 2020). Ensuring educators at all professional levels experience supportive organisational climates is essential to promote healthy wellbeing and resilience, to stem the high levels of turnover in the workforce, and to promote strong educator–family relationships (Hine et al., 2022; Thorpe et al., 2020).

Overall, indicators for family engagement were rated highly by all participant groups, demonstrating that educators responded to the pandemic-related challenges with a continued commitment to supporting children and families; efforts that were in turn appreciated by families. Specifically, five effective family engagement strategies were conceptualised from analyses of the open text survey responses: drawing on cultural, personal and professional knowledges to enrich children’s learning at home; prioritising regular and reliable communication with families; maintaining familiar relationships and a sense of community; providing person-centred supports and a bridge to other services; and nurturing mutually supportive educator–family relationships. Aligning with prior research, a person-centred approach was noted as a particularly important strategy to meet the diverse needs of families, and particularly for reaching families experiencing disadvantage (Jeon et al., 2020; Roberts, 2017). The bi-directional sharing of information between home and ECEC to enrich children’s learning was likely necessitated by the conditions of the pandemic, as was the need for both educators and families to draw on and share their own cultural, personal or professional knowledges to enrich children’s learning at home. In addition, the shared common challenges of the pandemic and disruptions to the usual educator–family power differentials in ECEC settings potentially contributed to increased empathy and the development of more trusting relationships between educators and families (McWayne et al., 2022; Purola & Kuusisto, 2021; Roberts, 2017). Nevertheless, the post-pandemic context provides an ideal opportunity to build on these practices, not least due to the increased need for effective early intervention (O’Connor et al., 2022; Prime et al., 2020), and the apparent renewed community appreciation for the important work of ECEC educators (Levickis et al., 2023).

As suggested in this study, increased community recognition of educators combined with a supportive organisational climate may contribute to an improved sense of professional wellbeing, which in turn may support educators’ capacity to build and maintain effective partnerships with families. In other words, there is a positive reinforcement cycle at play with potential reciprocal benefits for both family and educator wellbeing: the development of supportive, reciprocal relationships with families—buoyed by a supportive organisational culture and broader societal recognition of the important role of educators—can lead to improved educator wellbeing in that their role is more satisfying and valued, and this in turn can support educators’ capacity to nurture and care for families.

Sustaining trusting educator–family relationships that were strengthened during the pandemic, and continuing to embed practices that draw on a wealth of personal and cultural knowledges from both families and educators are essential to support engaging and meaningful family engagement programming. Promoting socially and culturally inclusive practices that reflect children’s everyday lives is particularly important for engaging disadvantaged or vulnerable children and families (McWayne et al., 2022; Roberts, 2017). Given the well-established disproportionately negative impacts of the pandemic on families who were already marginalised or experiencing disadvantage, effective and sustained family engagement efforts will be essential to minimising the adverse impacts of the pandemic in years to come.

Conclusion

Taken together, findings underline the importance of supportive organisational structures to support robust professional wellbeing, and relatedly, the significance of professional wellbeing and resilience as potential enablers for strong family engagement. While the effective family engagement strategies reported in this study were adopted in Australian ECEC settings within the context of a global pandemic, they are certainly transferable to other early learning settings and may offer significant potential benefits for educators, children and families in the post-pandemic context. However, if they are to be sustainable, efforts to support family engagement must also consider the burden on educators: i.e., educators at all levels must receive adequate professional recognition, resources and supports, so that they have the capacity, as well as the commitment, to continue their important work with children and families.

Limitations and directions for future research

A strength of this study is that it captures multiple perspectives from stakeholders at ECEC services across Australia, providing important insights about supports for educator wellbeing and family engagement, key levers of program quality. However, it should be acknowledged that the sample size is relatively small, and recruiting participants through an early learning provider may have resulted in both sampling and reporting bias. Nevertheless, the findings replicate prior research conducted with larger cohorts, particularly in relation to highlighting the importance of supportive organisational structures to support healthy educator wellbeing and family engagement in ECEC. In addition, findings suggest that educator wellbeing and resilience may be important enablers for family engagement, regardless of structural characteristics such as service size or location. Exploring avenues to bolster educator wellbeing may thus yield effective supports for quality practice across multiple domains. Future research might explore, with a more diverse sample, the significance of supportive organisational structures in fostering strong family engagement, as well as the effective family engagement strategies described by the participants in this study in the post-pandemic context. Professional learning for educators that focuses on the strategies that are known to be effective (i.e., drawing on families’ cultural and social knowledges to enrich children’s learning) should also be a priority.

Data Availability

Requests to access the data supporting the results presented in this paper should be made directly to the authors.

References

Armstrong, F. (2019). Social constructivism and action research: Transforming teaching and learning through collaborative practice. In F. Armstrong & D. Tsokova (Eds.), Action research for inclusive education (pp. 5–16). Routledge.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/socio-economic-indexes-areas-seifa-australia/latest-release

Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority. (2018). Guide to the National Quality Framework. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-03/Guide-to-the-NQF-web.pdf

Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority. (2017). National Quality Framework, quality area 6: Collaborative partnerships with families and communities. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/nqf/national-quality-standard/quality-area-6-collaborative-partnership-with-families-and-communities

Australian Government Department of Education. (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/EYLF-2022-V2.0.pdf

Barnett, M. A., Paschall, K. W., Mastergeorge, A. M., Cutshaw, C. A., & Warren, S. M. (2020). Influences of parent engagement in early childhood education centers and the home on kindergarten school readiness. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.05.005

Berger, E., Quinones, G., Barnes, M., & Reupert, A. (2022). Early childhood educators’ psychological distress and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 60, 298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2022.03.005

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 793–828). Wiley.

Brown, S. M., Doom, J. R., Lechuga-Peña, S., Watamura, S. E., & Koppels, T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect., 110, 104699.

Burchinal, M., Carr, R. C., Vernon-Feagans, L., Blair, C., & Cox, M. (2018). Depth, persistence, and timing of poverty and the development of school readiness skills in rural low-income regions: Results from the family life project. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 45, 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.07.002

de Souza Morais, R. L., de Castro Magalhães, L., Nobre, J. N. P., Pinto, P. F. A., da Rocha Neves, K., & Carvalho, A. M. (2021). Quality of the home, daycare and neighborhood environment and the cognitive development of economically disadvantaged children in early childhood: A mediation analysis. Infant Behavior and Development, 64, 101619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2021.101619

Eadie, P., Levickis, P., Murray, L., Page, J., Elek, C., & Church, A. (2021). Early childhood educators’ wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01203-3

Evans, S., Mikocka-Walus, A., Klas, A., Olive, L., Sciberras, E., Karantzas, G., & Westrupp, E.M. (2020). From “it has stopped our lives” to “spending more time together has strengthened bonds”: The varied experiences of Australian families during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.588667

Gilley, T., Tayler, C., Niklas, F., & Cloney, D. (2015). Too late and not enough for some children: Early childhood education and care (ECEC) program usage patterns in the years before school in Australia. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40723-015-0012-0

Goldfeld, S., O’Connor, E., O’Connor, M., Sayers, M., Moore, T., Kvalsvig, A., & Brinkman, S. (2016). The role of preschool in promoting children’s healthy development: Evidence from an Australian population cohort. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 35, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.11.001

Hine, R., Patrick, P., Berger, E., Diamond, Z., Hammer, M., Morris, Z. A., Fathers, C., & Reupert, A. (2022). From struggling to flourishing and thriving: Optimizing educator wellbeing within the Australian education context. Teaching and Teacher Education, 115, 103727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103727

Jackson, J. (2020). Every educator matters: Evidence for a new early childhood workforce strategy for Australia. Mitchell Institute, Victoria University. https://www.vu.edu.au/sites/default/files/every-educator-matters-mitchell-institute-report.pdf

Jeon, S., Kwon, K. A., Guss, S., & Horm, D. (2020). Profiles of family engagement in home-and center-based Early Head Start programs: Associations with child outcomes and parenting skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.02.004

Levickis, P., Murray, L., Lee-Pang, L., Eadie, P., Page, J., Lee, W. Y., & Hill, G. (2023). Parents’ perspectives of family engagement with early childhood education and care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(7), 1279–1289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01376-5

Logan, H., Cumming, T., & Wong, S. (2020). Sustaining the work-related wellbeing of early childhood educators: Perspectives from key stakeholders in early childhood organisations. International Journal of Early Childhood, 52, 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00264-6

McFarland, L., Cumming, T., Wong, S., & Bull, R. (2022). ‘My cup was empty’: The impact of COVID-19 on early childhood educator well-being. In Pattnaik, J., Renck Jalongo, M. (Eds) The impact of Covid-19 on early childhood education and care. Educating the young child, (vol 18). Springer.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96977-6_9

McMullen, M. B., Lee, M. S. C., McCormick, K. I., & Choi, J. (2020). Early childhood professional well-being as a predictor of the risk of turnover in childcare: A matter of quality. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 34(3), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2019.1705446

McWayne, C., Hyun, S., Diez, V., & Mistry, J. (2022). “We feel connected… and like we belong”: A parent-led, staff-supported model of family engagement in early childhood. Early Childhood Education Journal, 1–13.

Morgul, E., Kallitsoglou, A., Essau, C. A., & Castro-Kemp, S. (2022). Caregiver-reported changes in the socioemotional wellbeing and daily habits of children with special educational needs during the first COVID-19 national lockdown in the United Kingdom. Frontiers in Education, 7, 838938.

Niklas, F., Cohrssen, C., & Tayler, C. (2016). Parents supporting learning: A non-intensive intervention supporting literacy and numeracy in the home learning environment. International Journal of Early Years Education, 24, 121–142.

O'Connor, M., Greenwood, C.J., Letcher, P., Giallo, R., Priest, N., Goldfeld, S., Hope, S., Edwards, B., & Olsson, C.A. (2022). Inequalities in the distribution of COVID‐19‐related financial difficulties for Australian families with young children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 48(6), 1040–1051. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.13010

Pascoe, S., & Brennan, D. (2017). Lifting our game: Report of the review to achieve educational excellence in Australian schools through early childhood interventions. https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/research/LiftingOurGame.PDF

Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643.

Purola, K., & Kuusisto, A. (2021). Parental participation and connectedness through family social capital theory in the early childhood education community. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1923361. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1923361

Roberts, W. (2017). Trust, empathy and time: Relationship building with families experiencing vulnerability and disadvantage in early childhood education and care services. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(4), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.23965/AJEC.42.4.01

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200.

Thorpe, K., Jansen, E., Sullivan, V., Irvine, S., & McDonald, P. (2020). Identifying predictors of retention and professional wellbeing of the early childhood education workforce in a time of change. Journal of Educational Change, 21, 623–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09382-3

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2022). COVID-19 and children. https://data.unicef.org/covid-19-and-children/

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the educators, Centre Directors and families who contributed their time to take part in this project.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This project was funded by the Ian Potter Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors confirm there are no conflicts of interest, financial interests or benefits arising from the direct applications of this research.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the University of Melbourne’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Review reference: 2022-20550-28976-6).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murray, L., Eadie, P., Fong, M. et al. Educator wellbeing and family engagement in Australian early learning settings: perspectives of early childhood educators and families. Aust. Educ. Res. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00751-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00751-y