Abstract

Widening participation in higher education has led to the global expansion of universities, increased student and program diversity, and greater provision of flexible pathways into university. Critical to supporting a growing student body is helping all students develop their ability to communicate confidently and effectively in their academic communities. This research employs a collaborative benchmarking framework to explore academic literacy instruction in pathway or ‘enabling’ programs across nine Australian universities. While prevailing assumptions hold that such programs are overly diverse, the findings demonstrate that these programs have developed remarkably similar approaches; in particular, the investigation found that the programs all drew on established academic literacy models and reflected an emerging disciplinary coherence across the enabling education sector, despite the lack of a formal curriculum and standards framework.Kindly check and confirm the processed Article title is correct.This is correct

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The ability to use language to meet the complex demands of tertiary study is critical for individual student success (Wingate, 2015), yet ‘academic literacy’ is a contested term with a variety of different understandings in higher education (Baker & Irwin, 2016), underpinned by different models of instruction in academic communication. The appropriateness of these different models is subject to increasing scrutiny as universities adapt to the changing needs of students. Globally, widening participation initiatives have transformed universities from elite to mass institutions with diverse student populations (Callender et al., 2020; Trow, 2007). Demands for an increasingly professionalised workforce, along with growing expectations of wider access to education (Mandler, 2020) and government policy changes (Gale & Parker, 2013) have seen universities expand access and offer programs to support this diverse range of students.

Despite this diversity of offerings, there is broad agreement about what is expected of graduates from Australian universities. Most universities have developed university-wide graduate attributes or outcomes that describe the skills, knowledge and capabilities graduating students are expected to demonstrate. Developed independently by institutions, these graduate attributes reflect the individual university expectations and values that differentiate each from other universities. How these are interpreted, articulated, measured, and attributed is similarly determined at the individual university level, reflecting each university’s unique interpretation as there is no national agreement on such statements (Barrie, 2006). However, these graduate attributes are very similar (Osmani et al., 2015) and focus on capabilities that align with the expectations of the various levels of qualifications the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) (Australian Qualifications Framework Council, 2013) describes. Although not explicit in these descriptions, there is an understanding that to achieve success in the skills at Level 7 (undergraduate degree) a student will require academic communication skills. According to the AQF, a student graduating from an undergraduate degree (Level 7) will have the ‘cognitive, technical and communication skills’ to ‘analyse and evaluate information’, and ‘generate and transmit solutions’, knowledge and ideas to others (Australian Qualifications Framework Council, 2013, p. 13).

Similarly, most graduate attribute statements include critical thinking, communication, problem solving and information literacy skills (Osmani et al., 2015), all underpinned by academic literacy. Students’ success at university and the likelihood that they will continue in an undergraduate program is impacted by how prepared they are for the type of study they move into (Jansen & van der Meer, 2012). However, many university students come from a high school experience that is neither consistent (Pargetter, 2000) nor specifically focused on the capabilities required to succeed in all academic settings (Emerson et al., 2015) including being prepared for undergraduate academic literacy requirements. Further, non-school leavers now make up a significant proportion of new undergraduate students and come to university with varying levels of academic communication preparedness. Many of these students need support to develop additional academic literacy capabilities needed for success in tertiary study.

Despite an increased recognition of the value of academic communication development for all students, and a growing emphasis on improving access for a broad spectrum of equity groups, research into academic communication instruction in higher education has focused on programs directed toward specific student cohorts. This is the case for English language development for students from non-English speaking backgrounds, and, to a lesser extent, transition programs provided by some universities through selected first year undergraduate programs (Chanock et al., 2012; Dooey & Grellier, 2020). Further, while improving access and valuing diversity has contributed to a growing interest in the academic communication skills which underpin successful university study, there appears to remain an entrenched deficit approach to developing students’ academic communication abilities (Lea & Street, 2006; Lillis & Scott, 2007; Wingate, 2015), and an expectation that students engage with and reproduce dominant conventions of the academy (Lillis & Scott, 2007). These expectations are reflected in traditional approaches to teaching academic communication, focusing on the mechanics of writing through the provision of remedial support for students who struggle with the academic communication requirements of their discipline, or specialist courses for those from non-English speaking backgrounds. However, more contemporary approaches, such as genre-based and socialisation models, along with discipline-based approaches have moved toward a more inclusive method with instruction embedded in the wider curriculum (Wingate, 2018). Academic literacy approaches include a further and critical element, recognising the social constructedness of routinised academic discourses and calling for their transformation to incorporate more inclusive practices (Lillis et al., 2015).

Australian ‘enabling’ education programs provide a key pathway through which diverse students access and transition into undergraduate study. However, research into how these programs approach academic communication development has been limited. Although the higher education landscape includes a range of pathway, preparatory or bridging programs under these broad banners, the research presented in this paper is specifically focused on university programs which are funded through the Australian government’s enabling load funding arrangements.

Enabling programs are non-award programs and in 2020 they engaged some 32 000 students (Department of Education, 2022). Enabling programs transition into further study proportionately more students from defined equity backgrounds than other alternative pathways (Pitman et al., 2016). This includes students from low socio-economic status, regional and remote backgrounds, Indigenous Australians, and people with disabilities. Significantly, the proportion of students entering university via an Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR) pathway has declined, and students who undertake an enabling program experience more positive outcomes in undergraduate study than those entering through other alternative pathways (Li et al., 2022). The Australian Universities Accord Interim Report (O’Kane et al., 2023) proposes increasing higher education participation targets and recognises the important role of enabling programs, as these targets will only be achieved through expanding access and participation by students from priority equity groups.

Enabling programs are excluded from the AQF, having been developed separately by individual universities to meet the needs of local student groups. This has contributed to a perception that enabling programs across Australia are disparate (Pitman et al., 2016; Shah & Whannell, 2017) with little consistency in course development and teaching and learning approaches. This has resulted in a lack of sector wide recognition of consistent academic standards, quality, and learning outcomes, in some cases limiting the transferability options for students who successfully complete their enabling programs. In their 2015 audit of how academic communication development is addressed across enabling programs, Baker and Irwin concluded that there was ‘not enough cohesion and conversation amongst enabling programs to form a sector’ (p. 12). It is this contention that is challenged in this paper. Recent multi-institutional studies (Relf et al., 2017; Syme et al., 2021) suggest there are underlying commonalities across some programs (despite a lack of an external standards framework), with these programs often sharing pedagogical approaches, learning outcomes and assessment practices. Drawing on these studies, the National Association of Enabling Educators of Australia (NAEEA) (2019) proposed a set of Common Learning Outcomes for enabling education in Australia, arguing in a submission to the AQF Review that a consistent approach via common learning outcomes for enabling programs would enhance the quality and institutional transferability of qualifications (Seary, 2019). These Common Learning Outcomes provide a descriptor of the capabilities expected of students who exit an enabling education program in Australia and thus, while not formally mandated, can now provide a proxy standard for the sector. Broad based external benchmarking provides an effective mechanism for further exploring the extent of an emerging cohesion across the enabling education sector, including understanding the scope of any shared approaches to academic communication development across programs.

This examination of academic communication development in enabling programs extends on a broad benchmarking project (Davis et al., 2023) for the NAEEA which examined the comparability of standards and outcomes of enabling education programs at nine Australian universities. Each of these nine programs includes a core subject addressing academic communication requirements at a tertiary level. This academic communication study sets out to examine this core subject in each of these nine programs to answer the following questions:

-

To what extent is there a shared approach to academic communication development across these different enabling programs?

-

What models of academic communication development underpin the approaches taken in these programs?

Close examination of curriculum materials, assessment practices and student writing across nine different sites of practice allows a deep understanding of how enabling programs address academic communication requirements, providing a depth of understanding not available through broad desktop audit processes.

This academic communication study may provide a much-needed basis for ongoing work to improve academic communication outcomes for students in these programs and to support them to transition into further tertiary level study. It will help address concerns that the sector lacks comparability and transparency (Pitman et al., 2016; Shah & Whannell, 2017), and may contribute to a greater understanding of the degree to which enabling education is emerging as a coherent sector within higher education, allowing broader and more rigorous explorations of the role of the sector in widening participation efforts in Australia.

Context and background

To date there has been limited research on how enabling education programs approach the development of students’ academic communication abilities, although many studies acknowledge it is a critical component (Brett & Pitman, 2018; Davis & Green, 2023; Fudge et al., 2022; Relf et al., 2017; Syme et al., 2022). Other studies (Hunt & Baker, 2014; McNaught & Benson, 2015) focus on initiatives to enhance the outcomes of academic communication subjects in individual programs and specific contexts. In one of the few broader studies, Baker and Irwin (2015, 2016) conducted an audit of academic literacy provision across 26 universities, concluding that there was no consistent approach underpinning these programs, and that the field was ‘disparate and semi-disconnected’ (Baker & Irwin, 2015, p. 58). They argued, nevertheless, that there was a preponderance of skills and genre-based approaches, with differences between programs generally aligning with how long they had been established, including those that looked ‘backwards to mimic school’ (Baker & Irwin, 2015, p. 57) and those that, through more emphasis on disciplinary epistemologies, looked ‘forward to imitate undergraduate study’ (p. 57). However, recent studies suggest there is growing alignment across the sector and that enabling education programs are underpinned by more developmental and transformative approaches, including the provision of academic communication and literacy development. Relf et al. (2017) argue common guiding principles underpin curriculum approaches across three enabling programs, identifying the shared inclusion of explicit teaching of the often implicit ‘rules, values, knowledge and academic skills’ required of university study (p. v.). Similarly, Syme, et al. (2021) compared three enabling programs, finding a shared approach to academic communication, particularly critical reading and the use of scholarly sources to construct an academic argument.

Academic communication models

Approaches to language and literacy development are dependent on understandings of the nature of literacy and how students acquire writing expertise. Models to support academic language development have been defined and characterised in a range of ways. Carroll (2002) argues a prevailing ‘fantasy’ in academia contends that students who are adequately prepared for undergraduate study will know how to write well in any context they encounter in their studies (p. 2). This assumption is based on the notion that ‘good writing’ is an uncontested convention, a unitary skill applicable across contexts and disciplines, rather than an ideologically situated, socio-cultural construct that varies across contexts (Lillis & Scott, 2007). This approach supports what Lea and Street (2006) refer to as a skills-based knowledge transmission model, arguably the dominant approach to academic development in many university settings (Wingate, 2015) that has emerged from an emphasis on mastering the surface textual features of writing. This model supports learning of decontextualised ‘rules’ and patterns of formal academic language such as sentence structure, grammar and punctuation, which can then be transferred unproblematically to any context and discipline (Lea & Street, 2006). Students undertake study to ‘fix’ the deficits in their writing, usually through add-on learning support or English language programs that are often marginalised and on the periphery of the higher education sector (Bell, 2023; Hyland, 2009). A criticism of this approach is that it focuses on superficial transfer of learning, while literacy knowledge is highly complex and does not always lend itself to such ‘low-road’ transfer into disciplinary areas (Green, 2013). Further, it misrepresents academic literacy as a ‘naturalised, self-evident and non-contestable way of participating in academic communities’ (Hyland, 2009, p. 8), an approach which fails to appreciate the growing diversity of those same communities.

An alternative approach to academic communication instruction is an academic socialisation model (Lea & Street, 2006) that views writing in a discipline as being about both the linguistic features that form part of that discipline and an understanding of how knowledge is constructed in that discipline (Wingate &Tribble, 2012). Students become part of that discipline’s culture, and learn, then reproduce its rules as needed (Lea & Street, 2006). This academic socialisation model draws on genre and discourse theory, recognising the differences between disciplines and how they construct knowledge according to their unique genres. In a teaching and learning setting, the teacher expert is responsible for guiding the student novice to understand and become part of the culture in which they are studying. The ways in which the communicative purpose of the text, and the roles and relationships within the discourse community influence textual features is central to this approach (Flowerdew, 2020), but emphasis is still on the unproblematic reproduction of established rhetorical patterns. While specific linguistic features are more easily transportable between contexts, students can have difficulties when they move between disciplines as they grapple with the construction of discipline knowledge within their new discipline (Wingate, 2015).

Lea and Street (2006) propose a third model that adopts an academic literacy approach. This approach, drawing on socio-cultural linguistics and critical theories, regards writing and literacy as complex social activities, focused on meaning making and closely linked to identity, power and authority. Students are viewed as valued collaborators in an academic learning community, while the discursive norms of this community are recognised as dynamic and changeable, subject to disciplinary influences but also impacted by broader institutional structures, such as governments and market economies. Such an approach allows for more meaningful knowledge transfer (Green, 2013) to new contexts and, with its ethnographic focus, foregrounds why the demands of academic communication are often opaque and inaccessible for students from historically excluded groups (Lillis & Scott, 2007). Academic literacy practices become routinised, what Bourdieu labels ‘habitus’ (Hyland, 2009, p. 123), for those with access to the cultural resources to engage with ease in a university environment. This is significant in the context of widening participation and enabling education programs as it acknowledges systemic inequalities that are open to challenge and transformation, and positions students to recognise, interrogate and resist these inequalities.

These three broad models described by Lea and Street (2006) are reflected in further literature. In a review of academic literacy research, Li (2022) groups approaches to language and communication pedagogy similarly as language based, disciplinary based and sociocultural. Bhatia (2004) presents a historical perspective arguing progression of focus from the textualisation of lexico-grammar (the textual space), to the organisation of discourse (the tactical and professional space), and then to the contextualisation of discourse (social space). Flowerdew (2020) argues that an academic literacies model shifts the pedagogical focus from text to practice. It should be noted, however, that these models are not mutually exclusive, and effective literacy pedagogy draws on elements from different models (Lea & Street, 2006) through the various and often iterative stages of text and context analysis and text production (Wingate, 2015). A combination of models also allows for both ‘high-road’ and ‘low-road’ transfer to target disciplines, thus helping enabling courses to fulfil their purpose of preparing students for academic study (Green, 2013). These models are summarised in Table 1.

Benchmarking

The Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) defines benchmarking as a ‘structured, collaborative learning process for comparing practices, processes or performance outcomes’ (TEQSA, 2019, p. 7). Increasingly, higher education providers are expected to employ external referencing processes, including benchmarking, to evidence quality in the delivery of their programs and to inform ongoing improvements through collaboration with comparator institutions (Booth et al., 2016). External benchmarking of programs involves a structured process through which learning outcomes, assessment methods and student work samples are analysed to determine if they are of a comparable standard, that students are achieving comparable outcomes (Sefcik et al., 2018), and that they align with regulated standards such as the AQF in Australia. However, if benchmarking of teaching and learning in individual programs, both within and across institutions, is to generate authentic understandings that can contribute to improved practices, it must go beyond ‘tick and flick’ style methodologies (Lawson et al., 2015) and provide opportunities for open, dynamic, and rigorous dialogue (James, 2003). It is through immersion in this dialogue that academics are able to articulate the often implicit understandings and epistemologies that inform their routine practices (Reckwitz, 2002). Such a practice-focused approach can provide rich, qualitative data to supplement more quantitative based benchmarking data.

Methods

This academic communication study extends upon a broader benchmarking study (Davis et al., 2023) of nine enabling education programs across Australia. Collectively, the programs account for approximately 50% of student enrolments nationally (Department of Education, 2022) and were selected through purposive sampling from a total of 35 institutions which offer such programs (Department of Education, 2022). They are diverse in size, geography, and structure; are representative of all states and the Northern Territory; and are thus broadly representative of the sector.

The first stage of this broader benchmarking project employed a framework developed by Morgan and Taylor (2013) and refined through a pilot benchmarking project by Syme et al., (2021). Initial meetings of participating researchers from each institution established the parameters and protocols of the project and facilitated the establishment of a formal cross-institutional agreement and, consequently ethics approval was attained. These meetings also established the sense of collegiality which later supported the open and rigorous conversations (Taylor & Morgan, 2011) necessary for productive and authentic benchmarking. Consistent with Yin’s (2014) pre-planned and tightly structured approach to case study research, a benchmarking framework and templates were developed to ensure that consistent data protocols (Hyett, et al., 2014) were established to support rigour and comparability of results. A shared data repository was established, and curriculum documents, assessment tasks, marking rubrics and student samples were collated. Four student samples from three subjects, including study preparation, foundation mathematics and academic communication were blind marked by academic staff from three of the participating institutions, and results were recorded and discussed by the researchers. The curriculum documents from each subject were also compared against the Common Learning Outcomes established by the NAEEA (2019) to determine the extent of alignment. At each stage of this process, the researchers considered a series of questions relating to the benchmarking process and data collected. Notes made during these conversations provide rich evidence of the decision-making processes and epistemological understandings underpinning teaching practices.

Each of the programs included a core academic communication subject, focusing on reading academic texts and writing a formal academic research essay, and it is this subject that is the focus of this academic communication study. It must be noted that the academic communication subjects investigated in this study are not aimed at addressing English language skills for students from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. English language entry requirements are not consistent across all enabling programs (Baker & Irwin, 2015). While some universities also offer specific English language programs for CALD students, students in enabling programs may have differing levels of English language competency, which can impact on their learning success. This academic communication study aimed to construct a rich and detailed understanding of how academic communication requirements are addressed in the enabling education sector based on patterns which emerge across nine separate university programs. Curriculum and assessment documents were analysed against descriptors of the established models of academic communication (Lea & Street, 2006), including skills based, academic socialisation and academic literacy models. This aimed to determine the extent to which these models are reflected in this program documentation. Assessment tasks and rubrics were also analysed against these models. Relf et al., (2017, p. 3) argue such documents evidence the ‘intended curriculum’.

The benchmarking process provided opportunities for in-depth conversations amongst the researchers about their theoretical and practice-based approaches to academic literacy development. This evidence gathered through benchmarking is therefore supplemented by notes made during fortnightly participant meetings. Each participant contributed to these discussions as a ‘participant-as-observer’ (Cohen et al., 2017, p. 543) with insider knowledge of epistemological approaches, teaching practices, and assessment processes, providing a rich source of information about ‘enacted’ and ‘hidden’ aspects of the curriculum (Relf et al., 2017, p. 3). The participants engaged as practitioners and researchers and remained reflectively self-conscious of their role as insiders, and critically reflexive as they shared and analysed their authentic experiences (Cohen et al., 2017).

Results

Comparing curriculum outlines

The curriculum outline documents for the academic communication subjects included subject titles and codes, rationales, synopses, learning outcomes, assessment structures and expectations, and often study schedules and additional information for students regarding learning support, academic integrity and various relevant university policies. The learning outcomes, topics and assessment tasks for each subject, presented in detail in Davis et al. (2023), were compared. In all nine subjects, the topics for study and the learning outcomes included references to the elements and stages of academic essay writing, including researching, structuring, drafting, referencing, and presenting an argumentative essay. Five subjects included explicit references to understanding the university context, culture or environment, while three referred to learner identity and self-reflection.

All nine subjects adopted a remarkably similar assessment approach. In all but one subject, students selected and then engaged with a single research topic throughout the entire period of study. (In the remaining subject, students engaged in a series of specified themes rather than a single topic of study). Students then investigated this topic, developing growing expertise through their reading, and submitting a series of scaffolded assessment tasks reflecting the steps involved in developing an academic research essay. Tasks included direct responses to academic readings, such as an annotated bibliography, reading responses to set questions, journal reflections about readings, or a literature matrix, all designed to develop both information literacy and critical reading abilities, and student knowledge of the research topic. Students then submitted, in various stages of development, an evidence based and referenced paper in response to a set essay question or choice of questions. These tasks included essay proposals and plans, complete or partial drafts, and then the completed essay, with iterative feedback throughout this process (Fig. 1). Two subjects also included an end of semester examination drawing from the same essay project.

Most of the subjects offered a choice of essay topics that students could work on throughout the semester whilst the remaining programs provided one set topic. These topics were current and focused on areas that students were likely to already be familiar with or have an interest in such as media, social media, rural education, digital technology, online education, and climate concerns. These general topics allowed for a focus on the academic capabilities needed to complete the task, rather than specialised discipline knowledge. All subjects introduced the topics through academic readings at the beginning of the semester and structured the subject learning around this topic, introducing scaffolded skills development to arrive at the production of a final essay. Whilst the different subjects allowed for a range of essay types, they all required basic research skills to be incorporated into the final essays with an emphasis on writing structure, academic integrity and correct inclusion of appropriately selected source material. Carroll (2002) argues that a challenge of preparatory academic communication courses is that they do not easily afford students the opportunity to develop the disciplinary content knowledge (what to write) required to support the critical thinking underpinning academic writing processes (how to write). However, the shared adoption of this extended thematic approach, requiring students to engage with a range of theme based academic texts, lends more authenticity to the development of their academic essay.

The nine curriculum outline documents were also closely analysed for evidence of discourse relevant to each of the three academic communication teaching models. Using simple coding in NVivo 12, terms relevant to the three models of academic communication teaching were grouped to determine if there was a greater emphasis on one approach over others. Specific references to individual skills, such as punctuation and grammar, were evident throughout the documents, accounting for 30% of mentions, and matched to the skills model. References to understanding and using the features of specific academic genres, along with references to being aware of and responding to the demands of a university environment accounted for over 60% of all mentions, and were aligned to the academic socialisation model. Finally, references to developing critical approaches to university expectations, identity formation, and constructivist or collaborative meaning making were coded against the academic literacy model, and accounted for approximately 10% of mentions. While this analysis drew on quite arbitrary divisions of the content of the curriculum documents, the results reflect a strong reliance on the academic socialisation model, and an emphasis on a genre-based approach, while demonstrating a comprehensive approach that draws on elements of all three models (Wingate, 2015). While it is noted that curriculum outline documents are by their nature sparse, a simple analysis of their use of discourse reflecting terms most commonly associated with the different models of academic communication instruction gives an indication of their intention.

Analysing assessment rubrics

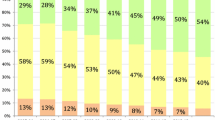

An analysis of the assessment rubrics also demonstrated a high degree of alignment across universities and a consistent reliance on a genre-based model, particularly as it applied to the formal academic research essay adopted by all nine subjects. For the purposes of comparison, the marking rubrics for the final essay assessments for each subject, each adding to a weighted result of 100%, were examined with the aim to categorise each criterion under similar overarching criterion types. For example, some rubrics assigned separate marks to an ‘introduction’ or a ‘conclusion’. These were included under the overarching criterion type ‘structure’. These overarching criterion types were added up to provide a total of the weightings out of 100% (Fig. 2).

It should be noted that the variation in criteria weightings across the universities may in part be attributed to the criteria weightings associated with previous assessment tasks which were not analysed here. These previous tasks generally required students to submit work in developmental stages as they progressed toward the completion of their final essay, such as essay plans and draft paragraphs.

Notably, the marking criteria in the rubrics were consistent across all universities. Whilst individual universities varied the weightings of the criteria, there was a strong emphasis on the essay structure and genre conventions associated with the type of essay required. The process around finding appropriate resource material and using it correctly in the essay was also given a consistently high weighting. This aligns with the overall emphasis on the higher order thinking skills required to produce the essay in line with academic expectations as seen by the relatively lower emphasis on the mechanical aspects of composing the essay with the focus on grammar, formatting, and spelling (Fig. 3).

Comparing mapping with NAEEA common learning outcomes

While benchmarking provides an opportunity for institutions to compare programs and individual subjects against those of comparator institutions (Morgan & Taylor, 2013), it also enables comparison with external standards (Booth, 2013; TEQSA, 2019). While enabling education remains unregulated as a result of exclusion from the AQF, the NAEEA Common Learning Outcomes for enabling education in Australia (NAEEA, 2019) provide a proxy standard.

The learning outcomes of the nine academic communication subjects were compared against these Common Learning Outcomes, using the following coding: ‘explicit’ indicates the outcome is articulated explicitly in curriculum documents; ‘implied’ indicates the outcome is addressed although not stated explicitly; and ‘not evident’ was used to indicate the reviewed documents provided no evidence of the outcome being addressed (Fig. 4).

Mapping of Academic Communication subjects and NAEEA Common Learning Outcomes. (Extract from Davis et al., 2023)

These results suggest there is deep congruence between approaches to academic communication across these subjects. While communication skills are an essential element of academic literacy, alignment with these common learning outcomes reflects an emphasis on the development of students’ capacities to understand and engage in university practices far beyond what would be expected from a model of academic communication which takes a predominantly skills-based approach. Further, while these Common Learning Outcomes are largely explicit in the nine academic communication subjects, they are also evident in other subjects which make up these programs and which have been explored in Davis et al. (2023).

Blind marking outcomes

Each university involved in the benchmarking study (Davis et al., 2023) submitted four student essay samples representing a range of grades. These were deidentified and blind marked by a further two universities, based on information provided in the assessment task and using the original rubric provided to the students. In total, 36 samples were marked, with 13 receiving identical grades across all three markers and 18 varying by one grade level (Fig. 5). This reflects a strong agreement about the standard of work expected of students. However, there were five samples where marking varied by more than one grade level. These outcomes generated considerable discussion amongst participants, particularly around the need to establish a shared interpretation of the context of assessment and the marking rubric (Bloxham et al., 2015). The consistent interpretation and application of criteria-based assessment rubrics is complex, often relying on tacit understandings shared by members of a knowledge community (Sadler, 2005). The high degree of alignment evident in this blind marking exercise reflects a shared understanding of the academic literacy demands required of students at this pre-tertiary level.

Alignment of grades from blind marking outcomes. (Extract from Davis et al., 2023)

Participant discussions

Throughout the benchmarking process, ‘incidental conversations’ (Syme et al., 2021, p. 581) allowed detailed comparisons of teaching practices at each institution, providing a rich opportunity for participants to clarify and articulate tacit understandings, and to reflect on and improve practices. Like the curriculum documents which reflected the ‘intended curriculum’ (Relf et al., 2017, p. 5), these discussions also revealed an emphasis on genre analysis and making explicit for students the context, purpose and rhetorical features of academic texts. Strategies for supporting student information literacy, particularly the ability to find, interpret, analyse, evaluate and reference appropriate sources, were also discussed at length. While analysis of the curriculum documents revealed a greater frequency of references to academic writing (a total of 242 references) than reading (112 references), discussions indicated that reading across a range of different academic text types and using strategies to scaffold student reading were a critical component of a shared approach to teaching.

Participant discussions also revealed a concern with supporting non-traditional students to develop confidence and capability as they learned to navigate unfamiliar and complex higher education environments. Participants consistently expressed a rejection of deficit models of disadvantaged students and valued the richness that the experiences of diverse students contributed to their classes. Some participants regarded institutional approaches to, as examples, assessment extensions and academic integrity as not adequately accounting for the challenges experienced by students from diverse or disadvantaged backgrounds, and consequently regarded explicit teaching of university discourses (Devlin & McKay, 2019) as important levelling strategies. This demonstrates an awareness of the power imbalances inherent in working in a tertiary environment with students from diverse backgrounds, and the complexities involved in ensuring that those same students are empowered to participate in a system which can disadvantage them. These discussions of the ‘hidden curriculum’ (Relf et al., 2017, p. 3) are further evidence of shared approach to academic literacy across these subjects.

Discussion

These findings demonstrate that enabling education programs across the participating universities have much in common, particularly so for the core academic communication subjects. Curriculum documents from the nine subjects reveal similar learning outcomes and content for study, aligning closely with the NAEEA Common Learning Outcomes (2019) for Australian enabling education programs. All subjects take a similar approach to assessment, with the use of scaffolded assessments leading to the completion of an academic research essay based on scholarly sources. The subjects are structured around a thematic approach which provides students with the opportunity to engage in authentic meaning making as they develop their knowledge of their selected essay topic alongside their abilities to develop and present an academic argument. There is also similar alignment across each of the rubrics against which student essays are graded. These rubrics all emphasise mastery of the specific textual features of the genre students are required to employ, but also the critical use of academic sources to inform an argument. Blind marking of student samples indicated a broad agreement of the standard expected of students. These comparisons challenge assumptions about the diverse nature of enabling education programs and reflect there is an emerging coherence in the sector. Enabling education programs, and specifically the academic literacy subjects, are closely aligned with each other. These findings support the case for portability of programs across institutions.

Findings also demonstrate these subjects adopt an academic literacy approach to teaching rather than an over reliance on a decontextualised skills-based model. All subjects culminate in the production of an academic essay which is purposeful and contextualised, engaging students in the meaningful production of knowledge. Through a common thematic approach structured around reading based tasks, students develop topic expertise, empowering them to engage in dynamic and authentic academic discussion, debate and knowledge production. Students search for and examine evidence from a range of academic texts, learning academic requirements around selecting and using resources appropriate for purpose. Within these scaffolded tasks the foundations for academic literacy are built, as the conventions of not only academic writing but of knowledge building in an academic community are introduced and practised. Students mobilise academic writing practices and conventions to build logically sound, well supported and coherently structured arguments to make and share meaning. This emphasis on authentic meaning making and context-specific patterns of discourse is evident in the range of literacy tasks demanded of students, and the dominance of content and structure related criteria in assessment marking regimes. Although some attention is given to the mechanics of writing, these skills are important only to the extent that they facilitate meaning making.

While academic communication subjects focus on the development of students’ ability to write a formal research based academic essay, this type of writing is only one of myriad literacy tasks students will encounter in higher education. It is notable that the nine universities adopted a common approach to academic literacy, particularly since the programs in the study developed independently and without policy-driven requirements for enabling programs in Australia. This suggests strong agreement among participants about the most appropriate approach to academic literacy development in this context. Roald et al. (2021) argue that students often view academic writing as rule-governed, restricted and stressful, yet it remains a preferred format for assessment tasks across many university programs. While student evaluations collected across the nine academic communication courses reflect a high degree of student satisfaction, (out of a possible ranking of five, all ranged between 4.0 and 4.8), qualitative student feedback indicates many found the task of writing an academic research essay challenging. However, it also reflects a recognition of the value of direct academic literacy instruction, as evidenced in these illustrative qualitative responses:

In the first week I was daunted but it became very clear that we are guided step by step through the course and I know that if I take advantage of the resources available and follow all the steps given to me I will do very well and learn important skills too.

Academic Writing is not like Mathematics, there is not a particular solution that you need to learn, it is a learning journey/experience. I don't think I have reached my full potential as of yet but I know as I progress through the studies, my academic writing ability will further progress.

Aware of student trepidation, enabling educators are well practised in scaffolding tasks to support students to produce high quality work, helping them prepare for further academic study by selecting this challenging and complex assessment task, the successful completion of which also supports the development of student self-efficacy and confidence. It requires students to learn, practise and demonstrate a wide range of academic literacy capabilities through a single capstone essay. It provides a scaffolded foundation for the genre awareness, knowledge building, research, critical thinking, and metacognition required in undergraduate study. A challenge for academic communication subjects in enabling programs, from which students articulate into a wide range of academic disciplines, is how to build students’ capacity to employ the features of genres which may cut across disciplines while developing an awareness of the discourse variations across genres and disciplines, along with an awareness of the rather arbitrary nature of these genres. Whilst general academic communication subjects cannot include explicit writing instruction that will account for all disciplines, they facilitate a foundational understanding, and make explicit the constructedness and, often, fluidness of academic conventions within and across disciplines. They provide students with a toolbox for analysing the requirements of a wider range of disciplinary based writing tasks. As noted by one student through a subject evaluation survey, it is ‘not just random writing’. In addition to these academic literacy subjects, each of the enabling programs in this study includes elective subjects which do include discipline content and knowledge and it is within these subjects that the basics of discipline specific language and epistemology are introduced.

Widening participation in higher education is an ongoing challenge, and pathway programs have a significant role to play in this agenda, particularly in light of new targets for higher education qualifications across the population (O’Kane et al., 2023). While enabling programs may have originally been envisaged as a remedial measure to ‘fix’ student academic deficits and provide educational opportunities for students who might otherwise lack access, they have evolved. While some commentators (e.g., Baker & Irwin, 2015) have contended that this evolution has resulted in over-diversification, this study has found that enabling programs have in fact developed a similar approach to preparatory education. The mechanisms underlying this common approach are worth further investigation and theorisation, but, based on the findings in this study, some possible explanations emerge. For example, DiMaggio and Powell (1983) contend that similarities between institutions that share an organisational field are likely, as the field matures, and these can be accounted for through institutional isomorphism. They argue that this occurs because of coercive or environmental pressures such as legislative requirements, mimetic tendencies as the practices of lead institutions are copied, and the establishment of normative standards. However, the concept of isomorphism may be inadequate to explain the common evolution. For one, the programs examined in this study developed independently and without formal external standards.

Yet experienced enabling educators across these programs have arrived at a common approach as they encountered similar challenges and issues helping diverse and often disadvantaged students participate in higher education. Through experience, they are aware that effective academic preparation extends beyond the transmission of academic skills. While an emphasis on the explicit teaching of academic skills is evident in curriculum documents, teaching approaches which help students to build their capacity to engage in often complex and tacit university practices and discourses have become central to these enabling programs. This ‘hidden curriculum’ (Relf et al., 2017, p. 5) is made explicit as programs focus on helping students develop the cultural resources to support their transition into higher education, and to position them to develop the graduate attributes expected of successful students. There is a shared recognition that providing students with the opportunity to develop cultural resources through engagement in an enabling program (Millman & McNamara, 2018) will also enhance their opportunities beyond their university experience. The provision of effective and appropriate academic literacy instruction is a critical part of this process. These understandings are, in fact, normative standards in the sector. While these similar approaches developed independently, the recent moves toward collaborative and collegial benchmarking of programs across different institutions provides the opportunity for the continued capability building of academics and the development of a sustainable community of practice aimed at informing the ongoing development of teaching practices (Sefcik et al., 2018) on a national level.

As the enabling education sector in Australia continues to grow, there is an opportunity for educators to take a critical approach to understanding and driving the factors influencing its direction, including the impacts of institutional isomorphism. The Australian Universities Accord (O’Kane et al., 2023) flags the need for an increasingly educated workforce and underscores the role of enabling programs in achieving educational targets. As the sector moves towards shared quality standards, it is important that these evolve through an ongoing and critical scrutiny of its practices, ensuring students are optimally prepared for future academic challenges. This includes grasping the drivers behind increasing alignment and discerning the extent that they signify the emergence of enabling education as a distinct subdiscipline within higher education. For now, the strong alignment evident across these programs counters comprehensively arguments that the sector is disparate, and supports more formal recognition of the comparability and portability of enabling education qualifications through a nationally recognised framework.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Australian Qualifications Framework Council. (2013). Australian Qualifications Framework: Second edition. Department of Industry Innovation Science Research and Tertiary Education. https://www.aqf.edu.au/framework/australian-qualifications-framework

Baker, S., & Irwin, E. (2015). A national audit of academic literacies provision in enabling courses in Australian Higher Education (HE) (Association for Academic Language and Learning, Issue). https://www.newcastle.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/349434/Baker-Irwin-2015-AALL-report-final.pdf

Baker, S., & Irwin, E. (2016). Core or periphery? The positioning of language and literacies in enabling programs in Australia. The Australian Educational Researcher, 43(4), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-016-0211-x

Barrie, S. C. (2006). Understanding what we mean by the generic attributes of graduates. Higher Education, 51, 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6384-7

Bell, D. E. (2023). Accounting for the troubled status of English language teachers in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(8), 1831–1846. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1935848

Bhatia, V. (2004). Worlds of written discourse: A genre-based view. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Bloxham, S., Hudson, J., den Outer, B., & Price, M. (2015). External peer review of assessment: An effective approach to verifying standards? Higher Education Research & Development, 34(6), 1069–1082. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1024629

Booth, S. (2013). Utilising benchmarking to inform decision-making at the institutional level: A research-informed process. Journal of Institutional Research, 18(1), 1–12.

Booth, S., Beckett, J., & Saunders, C. (2016). Peer review of assessment network: Supporting comparability of standards. Quality Assurance in Education, 24(2), 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-01-2015-0003

Brett, M., & Pitman, T. (2018). Positioning pathways provision within global and national contexts. In E. I. Agosti & E. Bernat (Eds.), University pathway programs: Local responses within a growing global trend (pp. 27–42). Springer.

Callender, C., Locke, W., & Marginson, S. (2020). Changing higher education for a changing world. Bloomsbury Academic.

Carroll, L. A. (2002). Rehearsing new roles: How college students develop as writers. Southern Illinois University Press.

Chanock, K., Horton, C., Reedman, M., & Stephenson, B. (2012). Collaborating to embed academic literacies and personal support in first year discipline subjects. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 9(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.9.3.3

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Taylor and Francis.

Davis, C., Syme, S., Cook, C., Dempster, S., Duffy, L., Hattam, S., Lambrinidis, G., Lawson, K., & Levy, S. (2023). Report on benchmarking of enabling programs across Australia to the National Association of Enabling Educators of Australia (NAEEA). NAEEA. https://enablingeducators.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Report-on-Benchmarking-of-Enabling-Programs-Across-Australia-2023.pdf

Davis, C., & Green, J. H. (2023). Threshold concepts and ‘troublesome’students: The uneasy application of threshold concepts to marginalised students. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(2), 286–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1799972

Department of Education. (2022). Student enrolments pivot table. https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/student-enrolments-pivot-table

Devlin, M., & McKay, J. (2019). Teaching regional students from low socioeconomic backgrounds: Key success factors in Australian higher education. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 29(3), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.47381/aijre.v29i3.244

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 8(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691229270-005

Dooey, P. M., & Grellier, J. (2020). Developing academic literacies. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 14(2), 106–119. https://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/download/631/435435479

Emerson, L., Kilpin, K., & Feekery, A. (2015). Smoothing the path to transition. http://www.tlri.org.nz/sites/default/files/projects/TLRI_Emerson_Summary%20.pdf

Flowerdew, L. (2020). The Academic Literacies approach to scholarly writing: A view through the lens of the ESP/Genre approach. Studies in Higher Education, 45(3), 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1576165

Fudge, A., Ulpen, T., Bilic, S., Picard, M., & Carter, C. (2022). Does an educative approach work? A reflective case study of how two Australian higher education enabling programs support students and staff uphold a responsible culture of academic integrity. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 18(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00099-1

Gale, T., & Parker, S. (2013). Widening participation in Australia in higher education: Report submitted to the Higher Education Funding Coucil for England (HEFCE) and the Office of Fair Access (OFFA). HEFCE. http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30064915

Green, J. H. (2013). Transfer of learning and its ascendancy in higher education: A cultural critique. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(4), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.719155

Hunt, J. W., & Baker, S. (2014). Embedding academic literacies in the enabling curriculum: Innovations to enhance successful student transitions into undergraduate study. (Proceedings of the FABENZ Challenges and Innovation Conference 2014). http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1340366

Hyett, N., Kenny, A., & Dickson-Swift, V. (2014). Methodology or method? A critical review of qualitative case study reports. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 23606. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.23606

Hyland, K. (2009). Academic discourse: English in a global context. Bloomsbury Publishing.

James, R. (2003). Academic standards and the assessment of student learning: Some current issues in Australian higher education. Tertiary Education and Management, 9(3), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2003.9967103

Jansen, E. P., & van der Meer, J. (2012). Ready for university? A cross-national study of students’ perceived preparedness for university. The Australian Educational Researcher, 39, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-011-0044-6

Lawson, R., Taylor, T., French, E., Fallshaw, E., Hall, C., Kinash, S., & Summers, J. (2015). Hunting and gathering: New imperatives in mapping and collecting student learning data to assure quality outcomes. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(3), 581–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.911249

Lea, M. R., & Street, B. V. (2006). The ‘Academic Literacies’ model: Theory and applications. Theory Into Practice, 45(4), 368–377. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/stable/40071622

Li, I. W., Carroll, D. R., & Jackson, D. (2022). Equity implications of non-ATAR pathways: Participation, academic outcomes, and student experience. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Li_UWA_Final.pdf

Li, D. (2022). A review of academic literacy research development: From 2002 to 2019. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 7(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-022-00130-z

Lillis, T., Harrington, K., Lea, M. R., & Mitchell, S. (2015). Working with academic literacies: Case studies towards transformative practice. Parlor Press LLC.

Lillis, T., & Scott, M. (2007). Defining academic literacies research: Issues of epistemology, ideology and strategy. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1558/japl.v4i1.5

Mandler, P. (2020). The crisis of the meritocracy: Britain’s transition to mass education since the Second World War. Oxford University Press.

McNaught, K., & Benson, S. (2015). Increasing student performance by changing the assessment practices within an academic writing unit in an enabling program. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 6(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v6i1.249

Millman, T., & McNamara, J. (2018). The long and winding road: Experiences of students entering university through transition programs. Student Success, 9(3), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v9i3.465

Morgan, C., & Taylor, J. A. (2013). Benchmarking as a catalyst for institutional change in student assessment. In K. Coleman & A. Flood (Eds.), Marking time: Leading and managing the development of assessment in higher education (pp. 25–39). Common Ground.

NAEEA. (2019). Common learning outcomes for enablng courses in Australia. https://enablingeducators.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/2019-Learning-Outcomes_Enabling-Courses_Australia_AB-002.pdf

O’Kane, M., Behrendt, L., Glover, B., Macklin, J., Nash, B., Rimmer, B., & Wikramanayake, S. (2023). Australian universities accord interim report. Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/australian-universities-accord/resources/accord-interim-report

Osmani, M., Weerakkody, V., Hindi, N. M., Al-Esmail, R., Eldabi, T., Kapoor, K., & Irani, Z. (2015). Identifying the trends and impact of graduate attributes on employability: A literature review. Tertiary Education and Management, 21, 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2015.1114139

Pargetter, R. (2000). Transition: From a school perspective. Journal of Institutional Research, 9(1), 14–21.

Pitman, T., Trinidad, S., Devlin, M., Harvey, A., Brett, M., & McKay, J. (2016). Pathways to higher education: The efficacy of enabling and sub-bachelor pathways for disadvantaged students National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Final-Pathways-to-Higher-EducationThe-Efficacy-of-Enabling-and-Sub-Bachelor-Pathways-for-DisadvantagedStudents.pdf

Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225

Relf, B., Crawford, N., O'Rourke, J., Sharp, S., Hodges, B., Shah, M., & Katersky Barnes, R. (2017). Lighting the path (way): Articulating curriculum design principles for open access enabling programs. Department of Education and Training. https://ltr.edu.au/resources/SD15-5063_NEWC_Relf_Final%20Report_2017.pdf

Roald, G. M., Wallin, P., Hybertsen, I. D., Stenøien, M., & J. (2021). Learning from contrasts: First-year students writing themselves into academic literacy. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(6), 758–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1813264

Sadler, D. R. (2005). Interpretations of criteria-based assessment and grading in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293042000264262

Seary, K. (2019). 134 National Association of Enabling Educators of Australia Submission 2. Australian Quality Framework review submissions. Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-reviews-and-consultations/consultations/australian-quality-framework-review-submissions/submission/9300

Sefcik, L., Bedford, S., Czech, P., Smith, J., & Yorke, J. (2018). Embedding external referencing of standards into higher education: Collaborative relationships are the key. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1278584

Shah, M., & Whannell, R. (2017). Open access enabling courses: Risking academic standards or meeting equity aspirations. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 21(2–3), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2016.1203370

Syme, S., Davis, C., & Cook, C. (2021). Benchmarking Australian enabling programmes: Assuring quality, comparability and transparency. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(4), 572–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1804825

Syme, S., Roche, T., Goode, E., & Crandon, E. (2022). Transforming lives: The power of an Australian enabling education. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(7), 2426–2440. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1990222

Taylor, J. A., & Morgan, C. (2011). Excellence in assessment project: Final report. Teaching and Learning Centre: Southern Cross University.

TEQSA. (2019). Guidance note: External referencing (including benchmarking). Australian Government. https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/default/files/guidance-note-external-referencing-v2-5.pdf?v=1555376082

Trow, M. (2007). Reflections on the transition from elite to mass to universal access: Forms and phases of higher education in modern societies since WWII. In J. J. F. & P. G. Altbach (Eds.), International handbook of higher education (pp. 243–280). Springer.

Wingate, U. (2015). Academic literacy and student diversity: The case for inclusive practice. Channel View Publications.

Wingate, U. (2018). Academic literacy across the curriculum: Towards a collaborative instructional approach. Language Teaching, 51(3), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444816000264

Wingate, U., & Tribble, C. (2012). The best of both worlds? Towards an English for academic purposes/academic literacies writing pedagogy. Studies in Higher Education, 37(4), 481–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.525630

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.

Acknowledgements

This paper extends on a benchmarking project which compared the enabling education programs across nine Australian universities, including those of the authors. The authors wish to acknowledge the work of other members of this benchmarking project including Dr Suzi Syme, Chris Cook, Dr Sarah Dempster, Dr Sarah Hattam, George Lambrinidis, and Dr Stuart Levy.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection and analysis, and manuscript drafting and revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report there are no relevant financial or non-financial interests to declare.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the University of Southern Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee: H21REA020: Benchmarking Australian Enabling Education Programs: A Comprehensive Framework. Research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, C., Lawson, K. & Duffy, L. Academic literacy in enabling education programs in Australian universities: a shared pedagogy. Aust. Educ. Res. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00729-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00729-w