Abstract

The significant shortfall of staff in the early childhood education and care (ECEC) workforce identifies an imperative not only to recruit educators but to support ongoing qualifications and career advancement of those within. Indeed, Shaping Our Future, Australia’s workforce strategy for 2022–2031 identifies qualifications and career development as key focus areas. Taking this imperative, we asked Who? and How many? within the Australian workforce are committed to ongoing study? Analysing a national survey (N = 1291), we examine characteristics of those studying (20.5%) intending (52.3%) or wavering about further study (18.7%). Study and study intention were associated with being younger and at early career-stage, identifying a positive message for career growth. Those who were older or working part-time were less certain about ongoing training. Those with long tenure in ECEC had higher rates of studying for non-ECEC qualifications. Implications for qualification pipeline, career pathways and workforce strategy are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, and in the context of Australia, the need to address shortfalls in the early childhood education and care (ECEC) workforce is urgent (OECD, 2019, 2021; UNICEF, 2019). Whilst attracting new educators is important, so too is retaining those already working in the sector and supporting them to gain qualifications that ensure delivery of high-quality experiences for children (Center on the Developing Child, 2021; Siraj et al., 2022). Indeed, encouraging and supporting educators to engage in study and build their careers in ECEC is imperative to advancing the goal of a sustainable, highly skilled and professionally valued workforce (Education Services Australia, 2021). Whilst key stakeholders in the ECEC sector including governments, service providers and peak organisations continue to invest in a range of workforce initiatives to support retention and build capability (Education Services Australia, 2021), studies on educator commitment and intention to engage in further study within the ECEC sector are scarce. Mounting research documents the significance of professional standing, pay and conditions, and community perception in sustaining and growing the ECEC workforce (Nutbrown, 2021; 2020b, 2023). Yet, there has been limited focus on the pipeline through which individuals who enter the workforce obtain the necessary educational credentials and continue building their skills for the diverse roles within the sector. A stronger research and policy focus on this pipeline is needed if the intent of investment in ECEC, namely to improve children’s learning and futures, is to be realised (Jackson, 2021; Nutbrown, 2021; Thorpe et al., 2023).

In this paper, we contribute to the evidence base by strengthening understanding of the identity of educators who are currently engaging in study or intending to undertake further study towards an ECEC qualification. Such evidence is a necessary first step in directing resources to support and grow Australia’s ECEC workforce. Taking a policy analysis focus, and applying quantitative methods to a large Australian dataset, we frame our study around Australia’s ECEC workforce strategy for the next decade, Shaping our Future (SOF) (Education Services Australia, 2021),

SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021) represents a ten-year commitment to address ECEC workforce challenges and calls for the commitment of all stakeholders to join forces to advance the strategy’s goals. The strategy is structured around six interrelated focus areas (FAs): FA1—professional recognition; FA2—attraction and retention: FA3—leadership and capability; FA4—wellbeing; FA5—qualifications and career pathways and FA6—data and evidence. The current study examines those FAs pertinent to the ongoing commitment and qualification of existing staff: retention (FA2) and qualifications and career pathways (FA5) (Fig. 1). We ask Who? and How many? are committed to ongoing study and attainment of ECEC qualifications from within ECEC in Australia. Our aim is to provide data and evidence (FA6) to inform actions proposed in SOF centred on retaining staff (FA2), and supporting qualification and career pathways (FA5), recognising these actions are interlinked and will contribute to other areas such as improved recognition (FA1), growing capability and leadership (FA3) and personal wellbeing (FA4). The focus of this paper and relationship with SOF are mapped in Fig. 1.

We commence by analysing the practice actions proposed in SOF, reviewing current evidence and identifying the specific data needs to inform practice.

Retention of the Australian ECEC workforce

Australia’s National Quality Framework (NQF)Footnote 1 requires service providers to have a qualified and skilled workforce with a minimum entry qualification of Certificate III in ECEC, at least 50% of educators holding a diploma level qualification or higher and a minimum of two degree-qualified teachers in most services (Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2020). Meeting these requirements is an ongoing challenge (McKinlay et al., 2018, 2022; Thorpe et al., 2023) that has been exacerbated by the Covid19 pandemic to the point of crisis (Crome, 2022; OECD, 2020). Across Australia, current staff waivers to exempt services from meeting regulated level of qualification is 9.3% of ECEC services (Roberts, 2022). SOF proposes three strategies within FA2 Attraction and Retention. These comprise

-

1.

Targeting diverse groups of individuals, to enrol in, and complete ECEC qualifications.

-

2.

Streamlining processes for recruitment of overseas trained educators and teachers.

-

3.

Developing resources to highlight career pathways in ECEC.

These strategies place emphasis on attracting new staff (Thorpe et al., 2023). Yet attracting appropriately motivated and qualified people into the sector is only one piece of the challenge in growing the workforce. Valuing and retaining high calibre staff is critical for positive child outcomes (Center on the Developing Child, 2021), whilst staff stress and turnover is detrimental (Logan et al., 2020; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2015; 2020b).

With regard to strategic targeting the SOF focuses on diversity. For example, SOF specifically identifies the need for targeted supports to enable growth of the Indigenous ECEC workforce. Beyond growing diversity, identifying those invested in further training and targeting supports to these individuals builds capability, ensures ongoing quality improvement and a pipeline of leaders. Data identifying those motivated to study further is a critical first step in building such capacity. So too is identifying those not studying and the potential barriers to their engagement. Further, understanding of the course of careers and the point at which further education and training is undertaken is critical in delivering appropriate messaging to motivate those considering further qualification or wavering in making this decision.

With regard to career pathways, SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021) suggests development of resources highlighting career pathways, and a national communications campaign to promote careers in ECEC (FA1-4). Yet, these focus only on attracting new educators and not sustaining engagement and retaining staff to pursue a career pathway in ECEC (Thorpe et al., 2023). Not only does the ECEC sector require attractive and accessible ways for individuals to enter the workforce, but it must also accommodate educators who are committed to obtaining further qualifications whilst continuing their work in ECEC (Education Services Australia, 2021).

Improving the qualifications and career pathways of Australia’s workforce

The national workforce strategy for the next decade seeks to strengthen the qualifications and career pathways of Australia’s workforce. The success of the strategy depends not only on the availability of individuals interested in a career in ECEC but also on growing and sustaining a thriving workforce (Thorpe et al., 2023). To meet the increasing demand to deliver high-quality ECEC, SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021) proposes three strategies within FA5 Qualifications and career pathways. These comprise

-

1.

Reviewing staffing and qualification requirements.

-

2.

Reviewing early childhood teaching programme requirements.

-

3.

Focussing on the quality of vocational education.

Whilst these strategies focus on the quality and consistency of education and training programmes, there is less focus on those within the sector who are currently studying or intending to study. Strengthening our understanding about those who are studying whilst working in ECEC provides additional information to support workforce development strategies at all levels (i.e. employers, education and training providers, governments).

SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021) identifies reviewing current qualification requirements and education and training to strengthen quality, improve consistency and reduce complexity. However, the document fails to deliver on enabling flexible career progression over the lifespan of those who are in the workforce. Encouraging and enabling longer-term career aspirations is critical in attracting and retaining educators. This gap identifies the necessity to establish a clear and coherent career framework for ECEC in Australia, that includes a nested qualification framework. Nutbrown (2021) recognises the absence of clear and coherent pathways in England. With the intent to raise the importance of qualifications and highlight the professional roles within the early years workforce, Nutbrown suggests an ECEC career progression structure and qualifications framework as a priority area of work to address challenges pertaining to the recruitment, retention, and career progression of educators.

With regard to qualifications, SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021) seeks more flexible and accelerated pathways to address current workforce shortages. However, there are concerns that shorter duration of qualification, quality of education and training across the board (Vocational Education and Training (VET) and Higher Education (HE)) and insufficient attention to the NQF in preservice programmes may deliver poor quality graduates (Boyd et al., 2020). Adding complexity is the range of early childhood teacher qualifications (i.e. birth to 5 years; birth to 8 years, birth to 12 years) (Boyd & Newman, 2019), with programmes having different strengths and challenges in developing professionalism and practice, primarily linked to the age range served (Jackson, 2021).

Recognition (FA1), Attraction (FA2), Capability (FA3) and Wellbeing (FA4)

Enabling engagement in study presents workforce challenges. For the those studying there are time and cost demands whilst for employers and policy makers there are tensions between the need to have staff working in the centre and need to encourage and support engagement in study. Continuing workforce shortages and the cost of studying, including reducing hours of work to manage study, present barriers to educators pursuing higher qualification (Nolan & Molla, 2021; Nutbrown, 2021; Thorpe et al., 2020a).

Efforts to enhance ECEC and improve the professional standing of the sector through upgrading qualifications have been a prominent feature of ECEC policy internationally (Nutbrown, 2021) and in Australia (Nolan & Molla, 2021) over the last decade. Whilst the number of qualified educators has increased, this effort has failed to result in commensurate improvements in professional recognition, remuneration and work conditions (Phillips et al., 2016) to sustain those who have followed this pathway and to encourage others to do the same. Perhaps not surprisingly, there is continuing evidence of educators undertaking higher level qualifications to leave the ECEC sector to take up teaching positions in schools where wages, conditions and community perceptions are more favourable (Phillips et al., 2016; Thorpe et al., 2020a). Educators in the ECEC sector, including those with degree qualifications, remain the most poorly paid in the education workforce (McDonald et al., 2018; Phillips et al., 2016) and many leave the sector because they do not earn enough to live (Phillips et al., 2016). Others depend on financial support from partners and family to support their basic living needs and continue to work in the ECEC sector (McDonald et al., 2018).

Alongside these workforce issues, studies have shown that community understanding and appreciation of the importance of ECEC impact the supply of educators and teachers, as well as the engagement, satisfaction and wellbeing of the workforce (Logan et al., 2020; Thorpe et al., 2020a). Studies have documented that some teachers, including preservice teachers, perceive that working in the ECEC sector is not ‘real teaching’ (Boyd et al., 2020). Alongside differences in wages and conditions, community perceptions and value placed on educators’ professional work can steer those enrolled in a bachelor qualification to seek employment in the school sector rather than ECEC sector (Boyd & Newman, 2019).

To advance the shared goal of building and supporting a workforce that is engaged in ongoing qualification and knowledge advancement, our research offers unique insights regarding educators who are choosing to engage in further study, focussing on who is studying and how many are pursuing further qualifications. We also investigate educators’ intention to study as an outcome to fully capture educators’ intent to pursue a career in ECEC.

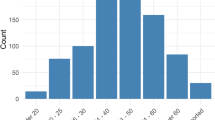

In this research, we aim to provide insight on those who are studying or intending to study to inform the development of strategies and related investment to encourage and support educator engagement in further study whilst working in ECEC. We present analyses of a large representative cross-sectional cohort of Australian ECEC educators (see Fig. 2) who are currently studying or intending to study. In analyses of the cohort data, we examine the association between educator’s demographic (age, current role, highest qualification, employment status, duration of service in both current centre and the ECEC sector) characteristics associated with their commitment and intentions to engage in further study within the ECEC sector. Recognising the complexity of the ECEC sector, including remuneration, organisational directives, characteristics of the community served and workplace ethos, we analyse two samples: (i) educators who are engaged in study (studying an ECEC qualification, studying a non-ECEC qualification, not currently studying); and (ii) educators who are intending to study (intending to study an ECEC qualification, undecided about further study, and not intending to study).

Method

Sample and procedure

We analysed data from the Early Years Workforce study (EYWS). The aim of the EYWS was to identify the personal, professional and workplace mechanisms associated with staying and training in the ECEC workforce.

In this study, we analyse data from a national online survey conducted as Phase 1 of this study between June 2015 and January 2016. Links to the online survey were disseminated through the national professional organisation (Early Childhood Australia), employing organisations and government agencies (e.g. Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority). The survey participants on whom we report were all practicing educators across the range of qualification levels and roles within an ECEC service. Survey items collected data pertaining to demographic, wage, professional and workplace characteristics and included key items on current engagement in study and intention to study. These later items were the focus of the two sub-studies detailed below.

Study 1 focussed on identifying the characteristics of those engaging in study and focussed on two key questions: Are you currently studying towards a further ECEC qualification? and Are you currently studying towards any other non-ECEC qualification? Our primary interest here was educators studying towards an ‘approved’ qualification linked to legislated roles in Australian ECEC (i.e. Certificate III in ECEC; Diploma of ECEC; Bachelor of Education (Early Childhood)). In Australian ECEC, a bachelor level teaching degree is currently the highest mandated qualification. A total of 1202 completed these questions from which three groups were derived (Studying ECEC qualification, Studying non-ECEC qualification, Not studying). The code Studying ECEC qualification included approved ACECQA qualifications under the National Quality Framework (ACECQA, 2020). Studying non-ECEC qualification includes qualifications spanning VET and HE (Australian Qualifications Framework Council, 2013). These formed the focus of statistical analyses in Study 1. The proportion of those in each group is presented in Fig. 3.

Study 2 examined intention to study, focussing on responses to the question I would like to gain further ECEC qualifications rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree though 5 = strongly agree). Responses aggregated into three groups—intending to pursue further qualification, not intending to pursue further qualification or neutral/undecided. A total of 914 completed the question I would like to gain further qualifications required for the current analyses aggregated into three groups (intending to study, wavering about study and not intending to study). Intending to study comprised participants who had indicated that they agree/strongly agree to further study. The code wavering about study comprised those who had indicated that they are neutral/unsure about further qualification. We define wavering as undecided but have not ruled out further study (as opposed to those who state they are not intending to engage in further study). Those coded as not intending to study indicated that they disagree/strongly disagree to further qualification. These groups formed the focus of statistical group comparison in Study 2. The proportion of those intending to study is presented in Fig. 4.

Data analysis and statistical procedures

All survey data were analysed using Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28.0.1.0. Descriptive data were generated using frequency counts and means. A multivariate analysis approach was incorporated to investigate the association of demographic and professional characteristics with educator current study enrolment and future study intentions. Specifically, multinominal regressions were included due to the flexibility of incorporating categorical variables as both predictors and as outcome measures.

Ethical approval

The research study was conducted in accordance with the ethical approval from the Queensland University of Technology University Human Ethics Research Committee Approval #1900000976. Data can be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Results

Study 1: Who is studying?

The aim of analysis of Study 1 was to identify who was choosing to engage in study whilst working in ECEC. Descriptive statistics and group comparisons are presented in Table 1. A multinominal regression was conducted to explore association of educator characteristics and membership of the three study groups: engaged (studying an ECEC qualification), studying to leave (studying a non-ECEC qualification) or not studying. The relationships between the engaged group and the two other groups were of most interest; therefore, the engaged group was selected as the reference group in the analysis. Predictors were entered simultaneously into analysis and included age (< 29, 30–39, 40–49, > 50), current ECEC qualifications (below minimum, VET, university), current role (educator, ECT, management), employment arrangements (casual, contract, permanent), work time (part-time, full-time), duration of service at centre (years) and in the ECEC sector (years).

The overall model was significant (χ2(24) = 145.74, p < 0.001) and results demonstrated less qualifications, the number of years in current centre as well as in the larger ECEC sector were significant predictors of study group (refer to Table 2). Those who held below minimum qualifications and VET qualifications were more likely (compared to university qualified) to be studying an ECEC qualification compared to those not studying. Educators who had spent fewer years at their centre were more likely to be studying an ECEC qualification compared to those not studying. Similarly, those who had spent fewer years in the ECEC sector were more likely to be studying an ECEC qualification compared to those not studying. Interestingly, those who had spent a longer time in the ECEC sector were more likely to be studying to leave (non-ECEC qualification) compared to studying an ECEC qualification.

Results Study 2: Who is intending to study?

Whilst Study 1 focussed on those currently studying, Study 2 examined intention to study—a step back in the workforce pipeline examined in Study 1. Amongst the sample (N = 914), we examined the characteristics of those (i) intending to study towards a further ECEC qualification, (ii) wavering or undecided about undertaking study towards a higher ECEC qualification but have not ruled out further study or (iii) not intending to undertake further study. Descriptive statistics and group comparisons are presented in Table 3. A multinominal regression was conducted to explore the characteristics of educators in the three study groups: engaged (intending to study an ECEC qualification), wavering (undecided about further study) or not intending to study. The relationships between the engaged group and the two other groups were of most interest; therefore, the engaged group was selected as the reference group in the analysis. The predictors included age (< 29, 30–39, 40–49, > 50), current ECEC qualifications (below minimum, VET, university), current role (educator, ECT, management), employment arrangements (casual, contract, permanent), work time (part-time, full-time), duration of service at centre (years) and in the ECEC sector (years).

The overall model was significant (χ2(24) = 90.00, p < 0.001) and results demonstrated that age, current role, work time and duration of service at centre were significant predictors of membership of intention to study group (refer to Table 4). Younger participants, specifically those in the < 29 and 30–39 groups, were more likely to be engaged compared to wavering or not intending to study. Additionally, those who were engaged worked fewer years in their centre compared to those not intending to study and wavering. Interestingly, ECTs (compared to managers) were more likely to be not intending to study compared to being engaged. Those who were working part-time (compared to full-time) were more likely to be wavering compared to being engaged.

Discussion

In this study, we analysed data from a national survey, conducted in 2016, to examine patterns of engagement in further study to gain qualifications in ECEC. The aim was to offer nuanced insights into educators who are studying or intending to study to inform the strategies and related investment to encourage and support educator engagement in further study. The strength of the study is in capturing the diversity of currently practising educators who engage in further study whilst working and potential ECEC leaders who enter with qualifications but may opt not to remain. The strength is also in the size and representation of the Australian population sampled. Additionally, the data are individualised and provide information on personal intent, whereas national administrative data sets (Australian Government Department of Education Skills & Employment, 2017) are collected at service level. We note, however, that the study predates the Covid19 pandemic that has further exacerbated a pre-existing national and international workforce crisis (Crome, 2022; Eadie et al., 2021; McFarland et al., 2022; OECD, 2019; Thorpe et al., 2020b). We also note that our focus was those already in the ECEC workforce and has the limitation that it does not include those in full-time training. The analyses presented are suited to identifying Who? and How many? are engaged in further study and qualification focussed on population proportions and patterns. The data remain pertinent to the key policy concern to build and sustain a high-quality ECEC workforce.

There is an urgent need to attract more teachers and educators to the sector (OECD, 2019, 2020; UNICEF, 2019); however, the challenge of workforce shortages cannot be overcome if those engaged in the workforce are not retained (Logan et al., 2020; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2015; Thorpe et al., 2020a) and supported to gain formal qualifications. Whilst the success of Australia’s ECEC workforce strategy SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021) places high emphasis on attraction of educators, our focus in the current study was retention and the pipeline to maintain and grow a thriving workforce who can deliver the quality of early education and care needed to promote children’s learning and development (Center on the Developing Child, 2021; Siraj et al., 2022). By investigating those already working in the Australian ECEC workforce, we sought to examine How many? and Who? are committed to ongoing study as indices of commitment to a career in ECEC. Building on the initiatives in SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021), our paper focuses on the pre-existing workforce across the diversity of roles and qualifications. Our data inform targets for support strategies both for those engaging (studying and intending to study) and undecided about study (wavering). By mapping our findings to SOF, we provide data and evidence (FA6) that adds to the existing areas of focus and offers more nuanced insight to inform targeted and tailored responses to support those who are already working in the sector. Three key messages emerge from our mapping:

Message 1: High levels of engagement in, and intention to study points to the need to increase study supports.

Our study found 20.5% of staff were engaged in study, 52.3% intending to do so and a further 18.7% wavering or undecided. Across all age groups, there were educators actively engaged in study; however, our analyses indicate that those most likely to study are younger and less qualified. The higher level of engagement of younger and less qualified educators is expected and reflects national policy. National legislation and minimum qualification requirements drive staff to engage in study (McKinlay et al., 2022). Australian legislation enables staff to work one-step beyond their current role without holding the minimum qualification, provided they are enrolled in the required qualification (ACECQA, 2021). At a time of workforce shortages, this provision offers an incentive and opportunity to grow a qualified workforce from within. Such provision may explain the high reported intention to study. However, identifying how intention is converted to reality should be further investigated. For example, the Australian ECEC workforce comprises 97% women. Thus, career path is complicated by reproductive life course that includes pregnancy and care duties (McDonald, 2018). We note that our findings show that amongst those working part-time, a work pattern associated with care duties, there are higher levels of wavering about further study. Prior evidence suggests birth of children, child and family care responsibilities and disruptions associated with spouse employment are important influences in ECEC workforce engagement (Thorpe et al., 2020a). Consideration of innovation in support mechanisms to enable study for women who have care responsibilities is required.

SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021) names strengthening leadership and capability (FA3) and qualifications and career pathways (FA5) as areas of focus. The key strategies put forward are induction of new entrants, professional development opportunities (FA3-1), provision of micro-credentials (FA3-2) and establishing professional networks (FA3-3). There is little focus on formal qualification and career pathways (FA5) for those already in the workforce. Our findings flag a risk of loss of educators if mechanisms to provide support for further training are not in place. Moreover, incentives for further qualification is limited for upward career paths.

Message 2: Truncated career pathways should be a catalyst for innovation

To advance a career in ECEC requires study for higher level qualifications (ACECQA, 2020; OECD, 2019). The finding that experienced educators up to the age of 39 are more engaged in study likely reflects this motivation. However, our results also present evidence of a truncated career pathway. We found that those with a degree qualification were less likely to engage in further study, whilst those who had spent many years in the ECEC sector were over-represented in the group studying towards a non-ECEC qualification. These findings may reflect a limited pathway beyond the role of Early Childhood Teacher for most, and align with the reported ‘qualifying out’ of the ECEC sector of more qualified staff, who seek better remuneration and work conditions (Thorpe et al., 2023).

SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021) acknowledges the current lack of contemporary research and publicly available information about clear, attainable career opportunities both for the current and future workforce. The document names the intention to develop resources to highlight the careers and career pathways available within the sector (FA2-3) for prospective job seekers, employers and employment services providers. Our findings underscore the importance of moving beyond a public relations campaign that highlights current opportunities to innovations in career specialisms that provide a pipeline for the current workforce and incentivise career advancement. Nutbrown (2021) has proposed a broader qualification and career framework, including specification of degree qualifications tailored to leadership roles in ECEC.

Message 3: Uncertainty or reluctance to engage in further study places a threat to a qualified workforce pipeline

Committing to study, although not a singular or direct measure is one index of career commitment and professionalism. Optimally, those with lower level qualifications would be engaging in further study, forming the ongoing pipeline of educators and teachers for the future and supporting improvements in quality of provision (Center on the Developing Child, 2021; Siraj et al., 2022).

Our data indicate that one in four (25%) of minimally qualified educators (Cert III) are not studying and do not intend to engage in further study; (50%) are already engaged in further study and the remaining 25% addition are considering study. That this, mainly young, group is so highly engaged is encouraging. The finding signifies that engagement of the majority (75%) of younger educators who provide the pipeline for the more highly qualified educators into the future.

Those educators wavering present an important strategic group to engage and support as our evidence shows reluctance to engage in further study increases with age. Without an incentive to start, and ongoing practical support to engage and complete an ECEC qualification, there is a risk that these groups will not engage in study. A broader qualification and career framework provides a roadmap to promote career aspirations and enable educators to advance their careers.

Whilst SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021) acknowledges higher qualifications are strongly associated with improved child outcomes, the detailed strategies tend to focus on attraction and provide few incentives for ongoing qualifications within the workforce. Micro-credentials (FA3-2) are being promoted as a panacea for attracting educators and building qualifications from within. Whilst micro-credentials may be one solution for those wavering, consideration needs to be given to how courses are delivered to those showing the greatest interest within the workforce, with our study highlighting the > 29 and 30–39 age group. There is need to consider the challenges and enablers to study whilst working in ECEC, such as personal and workplace supports (McKinlay et al., 2022), and for key stakeholders to work together to offer flexibility and wrap around support to enable educator engagement and ensure study completion.

Implications

This research has uncovered several important factors to be considered towards supporting ongoing qualification and career advancement in ECEC. Whilst recognising that the strong focus on attraction of new staff in SOF (Education Services Australia, 2021) reflects staffing shortfalls, we assert the equal need to support and retain those already within the workforce. Such support is not only about ‘keeping them in’ (retention) but is an investment in quality. Continuity of staff supports relationships with children (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2015), whilst ongoing qualification is a requisite of the professionalism specified in Shaping our Future (FA1) and in the professional recognition so strongly sought by those within the sector (Thorpe et al., 2020b, 2023). Encouraging, enabling and rewarding ongoing qualification is an investment in the future pipeline of educators, teachers and leaders in ECEC and essential to support and sustain the quality of provision for the benefit of all children and the nation.

Notes

The NQF is the regulation and quality assurance framework for ECEC and school age care in Australia; it comprises national legislation and regulations, a national quality standard, two Approved Learning Frameworks and an assessment and rating process.

References

Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2020). Qualifications for centre-based services with children preschool age or under. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/qualifications/requirements/children-preschool-age-or-under

Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2021). Actively working towards a qualification. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/qualifications/requirements/actively-working-towards-a-qualification

Australian Government Department of Education Skills and Employment. (2017). 2016 National Early Childhood Education and Care Workforce Census report. https://www.dese.gov.au/uncategorised/resources/2016-national-early-childhood-education-and-care-workforce-census-report

Australian Qualifications Framework Council. (2013). Australian Qualifications Framework. www.aqf.edu.au

Boyd, W., & Newman, L. (2019). Primary + Early Childhood = chalk and cheese? Tensions in undertaking an early childhood/primary education degree. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 44(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939119841456

Boyd, W., Wong, S., Fenech, M., Mahony, L., Warren, J., Lee, I., & Cheeseman, S. (2020). Employers’ perspectives of how well prepared early childhood teacher graduates are to work in early childhood education and care services. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 45(3), 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939120935997

Center on the Developing Child. (2021). Brain Architecture. Harvard University. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/brain-architecture/

Crome, J. (2022). A crisis in search of a narrative: Australia, COVID-19 and the subjectification of teachers and students in the national interest. Australian Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00550-3

Eadie, P., Levickis, P., Murray, L., Page, J., Elek, C., & Church, A. (2021). Early childhood educators’ wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01203-3

Education Services Australia. (2021). “Shaping Our Future” A ten-year strategy to ensure a sustainable, high-quality children’s education and care workforce 2022–2031. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-10/ShapingOurFutureChildrensEducationandCareNationalWorkforceStrategy-September2021.pdf

Jackson, J. (2021). Developing early childhood educators with diverse qualifications: The need for differentiated approaches. Professional Development in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1876151

Logan, H., Cumming, T., & Wong, S. (2020). Sustaining the work-related wellbeing of early childhood educators: Perspectives from key stakeholders in early childhood organisations. International Journal of Early Childhood, 52(1), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00264-6

McDonald, P. K. (2018). How ‘flexible’ are careers in the anticipated life course of young people? Human Relations (new York), 71(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717699053

McDonald, P., Thorpe, K., & Irvine, S. (2018). Low pay but still we stay: Retention in early childhood education and care. Journal of Industrial Relations, 60(5), 647–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618800351

McFarland, L., Cumming, T., Wong, S., & Bull, R. (2022). ‘My Cup Was Empty’: The impact of COVID-19 on early childhood educator well-being. In (Vol. 18, pp. 171–192). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96977-6_9

McKinlay, S., Irvine, S., Brownlee, J. L., Whiteford, C., & Farrell, A. (2022). Who is studying what in Early Childhood Education and Care? Composite narratives of Australian educators engaging in further study. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1177/18369391221118699

McKinlay, S., Irvine, S., & Farrell, A. (2018). What keeps early childhood teachers working in long day care?: Tackling the crisis for Australia’s reform agenda in early childhood education and care. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 43(2), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.23965/AJEC.43.2.04

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2015). Supportive relationships and active skillbuilding strengthen the foundations of resilience. Harvard University Center on the Developing Child, 13. Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu

Nolan, A., & Molla, T. (2021). Building teacher professional capabilities through transformative learning. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 49(4), 450–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2020.1828823

Nutbrown, C. (2021). Early childhood educators’ qualifications: A framework for change. International Journal of Early Years Education, 29(3), 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2021.1892601

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). Good practice for good jobs in early childhood education and care. OECD.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). Building a high-quality early childhood education and care workforce: Further Results from the Starting Strong Survey 2018.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2021). Building the future of education. OECD.

Phillips, D., Austin, L., & Whitebook, M. (2016). The early care and education workforce. Future of Children, 26, 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2016.0016

Roberts, J. (2022, 2022-11-06). Staffing waivers rise to new highs, quality continues to rise: Latest ACECQA snapshot. Retrieved from https://thesector.com.au/2022/11/07/staffing-waivers-rise-to-new-highs-quality-continues-to-rise-latest-acecqa-snapshot/

Siraj, I., Melhuish, E., Howard, S. J., Neilsen-Hewett, C., Kingston, D., De Rosnay, M., Huang, R., Gardiner, J., & Luu, B. (2022). Improving quality of teaching and child development: A randomised controlled trial of the leadership for learning intervention in preschools. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1092284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1092284

Thorpe, K., Jansen, E., Sullivan, V., Irvine, S., McDonald, P., The Early Years Workforce Study, t., Irvine, S., Lunn, J., Sumsion, J., Ferguson, A., Lincoln, M., Liley, K., & Spall, P. (2020a). Identifying predictors of retention and professional wellbeing of the early childhood education workforce in a time of change. Journal of Educational Change, 21(4), 623–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09382-3

Thorpe, K., Staton, S., Houen, S., & Beatton, T. (2020b). Essential yet discounted: COVID-19 and the early childhood education workforce. The Australian Educational Leader, 42(3), 18–21.

Thorpe, K., Panthi, N., Houen, S., Horwood, M., & Staton, S. (2023). Support to stay and thrive: Mapping challenges faced by Australia’s early years educators to the national workforce strategy 2022–2031. The Australian Educational Researcher, Undefined-Undefined. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00607-3

UNICEF. (2019). The state of the World’s children 2019. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-of-worlds-children-2019

Acknowledgements

The Early Years Workforce Study was funded under the ARC Linkage scheme (LP140100652) conducted by Queensland University of Technology, University of Queensland, and Charles Sturt University, in collaboration with the Queensland Department of Education and Training (now Department of Education), C&K (Childcare and Kindergarten) Queensland and Goodstart Early Learning. We gratefully thank Adjunct Professor Jo Lunn Brownlee for her support.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

None to declare.

Ethical approval

The research study was conducted in accordance with the ethical approval from the University of Human Research Ethics Committee at Queensland University of Technology (Approval Number 1900000976). Data can be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McKinlay, S., Thorpe, K., Whiteford, C. et al. Australia’s ECEC workforce pipeline: Who and how many are pursuing further qualifications?. Aust. Educ. Res. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00715-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00715-2