Abstract

This article utilises recent Australian schooling policies and associated international educational policies as a stimulus to reflect on the extent to which schooling provides genuinely ‘educational’ opportunities for students. To do so, the article draws upon Gert Biesta’s notion of the ‘risk’ of education to analyse the extent to which recent and current key federal government policies in Australia, and significant OECD and UNESCO policies, seem to enable more educationally-oriented schooling. The article reveals that while there are multiple discourses at play in relation to federal government policies, the way in which these policies have become more ‘national’ in orientation, and the attendant prescriptive attention to ‘capturing’ students’ learning in more and more ‘precise’ ways, mitigate against the possibilities for more risk-responsive schooling opportunities for students. While educational policies are always open to contestation in their enactment, more economistic and managerial foci within these texts militate against more productive, ‘risky’, learning. As a consequence, Australian schooling policy is a ‘risky proposition’—not because it places students ‘at risk’ of harm but because it does not draw sufficiently upon notions of risk as a resource to inform educational provision in preparation for living in an uncertain world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

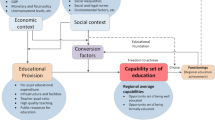

Educational provision is a challenging task for governments today. Broader, global discourses, most obviously associated with various market-oriented/neoliberal policies, challenge social practices in a range of areas as diverse as labour relations, race, gender, migration, housing and biotechnology (Springer et al., 2016). At the same time, more managerial practices, associated with organizational restructuring and a focus on breaking social practices down into specific units which can be subject to ever increased measurement and efficiencies, are also at play (Klikauer, 2015). Education provision through schooling is influenced by these more economistic and managerial factors—factors that seek to reduce the ‘risk’ of education provision.

Notions of risk can be understood in multiple ways. In more vernacular parlance, ‘risk’ is construed as a ‘problem’, something to be mitigated—something to be managed to reduce potential negative effects. However, defining risk is also a political act and can be understood as reflecting particular sets of values of those seeking to ascertain the nature of any given risk (Fischhoff et al., 1984). In this article, in the context of educational settings, and after Biesta (2016), risk is understood as a necessary aspect of any education worthy of the name. Biesta (2016) argues for greater acceptance of the ‘weakness’ of education, by which he means that ‘educational processes and practices do not work in a machine-like way’ (p. x)—that is, they are not easily subject to more managerial logics. Consequently, any educational experience always entails some element of risk. Risk is not something to be eradicated or simply ‘managed’ but instead something to be valued, anticipated and indeed, embraced. However, the extent to which schooling policies actually embrace such a conception of education, and enable the sorts of ‘risk-taking’ necessary for students of today, citizens of tomorrow, to be responsive to a constantly changing (and sometimes challenging) world, is open to question. An analysis that advocates for a ‘risky’ approach to Australian schooling policy as inherently educational is novel in recent schooling policy studies.

This paper draws upon recent schooling policies at the Australian federal government level to reflect on the extent to which current policy conditions enable the cultivation of such ‘risky’ learning on the part of students. There is a need to cultivate forms of resilience amongst children and young adults which enable them to develop the skills and dispositions to challenge their fears as they face the uncertainties and vicissitudes of life. This includes in the context of increased precarity in work and concerns about deteriorating mental health (Irvine & Rose, 2022), as well as increasing rates of anxiety amongst young people (Goodwin et al., 2020), including in the wake of COVID-19 (Meherali et al., 2021). Gert Biesta refers to the ‘beautiful risk of education’ to try to capture the open-ended nature of educational experiences and the need for institutionalised educational provision (in this case, schooling) to be open and adaptive to such risk-taking. Seeking to explore whether and how educational policy promotes the conditions for such risk-taking is crucial for attempting to cultivate risk-taking at the level of practice.

Empirically, the article draws upon key Australian schooling policy texts and related artefacts, and associated international policies, to explore whether such policies seem to cultivate the conditions for a more open-ended, ‘riskier’ approach to education. Alternatively, such policies may be associated with a narrower, more conservative conception of education. The paper begins by outlining the nature of Biesta’s argument about risk and education, and related literature, followed by an overview of dominant conceptions of accountability and increased attention to various numeric forms of data which constitute ‘anti-risk’ approaches to education. The article then provides an overview of the Australian educational context more broadly, including key policy texts and artefacts to be analysed. An analysis of these policy texts reveals multiple discourses at play. The paper concludes with a summative discussion about key findings and implications arising from this analysis.

The beautiful risk of education

Gert Biesta makes a cogent case for the need for education as something that is necessarily ‘risky’. It is not possible to ‘sanitise’ educational experiences or to mitigate the risk that something may go wrong as part of the educational experience. However, the policy conditions within which education is undertaken in schooling settings mitigate against broader educational aims through their advocacy for a narrower conception of educational attainment.

For Biesta (2016), the focus upon educational achievement and attainment has marginalized the very education required to achieve such ends. In an effort to ensure the results of education become more secure, and predictable—‘stronger’ and ‘risk-free’—Biesta argues education is at risk of being eviscerated. Furthermore, such ends have become targets to be achieved, rather than resources or tools that might be employed to provide insights into some aspects of attainment but that cannot capture the necessarily complex, nuanced and esoteric nature of learning itself. While academic results are important, there is not a clear match between the investment in education (‘inputs’ in terms of teaching practice, resources etc.) and what arises (‘outputs’):

Yes, we do educate because we want results and because we want our students to learn and achieve. But that does not mean that an educational technology, that is, a situation in which there is a perfect match between ‘input’ and ‘output’ is either possible or desirable. And the reason for this lies in the simple fact that if we take the risk out of education, there is a real chance that we take out education altogether (p. 1).

However, removing risk in relation to education is what teachers are increasingly called upon to do. This is achieved through attention to specified ‘learning outcomes’ and increased focus upon particular subjects—most notably literacy, numeracy but also science.

These circumstances exacerbate the challenges of promoting an education that necessarily accounts for the continuous interplay between the individual and the social circumstances/society in which they are located. Education entails a process of ‘becoming’ that cannot be easily captured in dualistic arguments about control and freedom—where the former entails subjection to society, whilst the latter entails freedom from such. Rather, education is a dialogic process which has as its aim the transformation of previous understandings—an interplay between individualistic desires and what may be desired when engaged with others. It is this interplay which shifts the focus from the individual desires to broader outcomes in relation to the needs of others and of a more progressive society more generally:

The educational concern rather lies in the transformation of what is desired into what is desirable… It lies in the transformation of what is de facto desired into what can justifiably be desired – a transformation that can never be driven from the perspective of the self and its desires, but always requires engagement with what or who is other (which makes the educational question also a question about democracy) (p. 3; emphasis original).

Biesta goes on to elaborate that education is therefore dialogic, and as a result, a slow process, for which the ultimate effects/outcomes cannot be predicted. This makes the educational way challenging, slow or what Biesta describes as ‘the weak way,’ (p. 3), given its outcomes are never assured. In short, education on this understanding is a ‘risky’ undertaking. It is not simply a process of ‘socialisation’ into the world but how to assist children to engage with the world, to ‘come into, the world’ (p. 5).

Biesta’s understanding of risk has also been taken up in different fora in an effort to foster more transformative and alternative approaches to educational provision. Christensen, Ekelund, Melin and Widén (2021) draw upon Biesta’s notion of beautiful risk to foster the development of collaborative and interdisciplinary research as part of an autoethnographic self-reflective approach in a university setting. While interdisciplinarity is described as inadequately recognised in relation to more traditional grant-giving institutions, and within universities more generally, interdisciplinarity is foregrounded as a more generative form of learning for research and higher education. Christensen et al. (2021) flag Biesta’s argument about the significance of ‘weak education’ as a vehicle to promote openness, complexity and unpredictability—necessary conditions to enable the very possibility of ‘thinking differently’. Loughland and Clifton (2023) similarly reflect on how the uncertainty associated with professional experience provision (work-integrated learning) for teacher education students in schools during COVID-19 could be reinterpreted as an opportunity for learning. Openness, complexity and unpredictability are necessary parts of the educational experience.

Biesta is not the only scholar who makes reference to ‘beautiful risks’ in education. In their conception of ‘beautiful risks’, Beghetto and Glăveanu (2022) refer to various ‘pedagogies of the possible’—in relation to fostering transformational giftedness education. Beghetto and Glăveanu (2022) advocate the notion of beautiful risk to foster the development of new pedagogical experiences, and how various ‘creative learning experiences’ can be cultivated in educational settings. These pedagogies of the possible are characterised by: a) open-endedness in design; b) non-linearity, enabling back and forth between ideas; c) pluri-perspectivism, involving eliciting multiple perspectives, and; d) a future orientation. An example is open-ended tasks requiring students to solve real-world problems, addressing injustices or specific issues facing them as they seek to enhance their own or other people’s circumstances. This could relate to, for example, how to better respond to homelessness in students’ local neighbourhoods, or mitigate climate change at a local level (such as by reducing electricity use in the home or school). These tasks require pedagogies that help build students’ understandings of the nature and influence of such problems/issues and involve to-and-fro with those influenced by these issues and knowledgeable ‘others’. (Such an approach may entail seeking homeless people’s perspectives about their needs and council/municipal officials about why certain strategies/approaches may not have worked in the past. It may also involve engaging with school personnel (teachers, janitors, office staff) and external experts (e.g., local electrical contractors) about how electricity is currently used in school settings, and ways this could be reduced). These pedagogies enable ‘beautiful risks’ to occur at both the level of pedagogical development to transform key educational experiences and at the level of students who are provided opportunities to take risks as a core part of their learning experiences. This work draws on Beghetto’s (2018) earlier, more descriptive volume about Beautiful risks: Having the courage to teach and learn creatively. However, unlike Biesta, Beghetto’s (2018) conception of beautiful risks is oriented towards more individualistic and psychologistic conceptions of acting. This is in contrast to Biesta’s broader philosophical conception which invites a wider understanding of risk, and which seeks to more overtly challenge established and institutionalised practices.

Nevertheless, Biesta’s work has also been critiqued, even as it has been actively supported by scholars. Yosef-Hassidim (2016) flags how the value of Biesta’s work lies in how it focuses upon education as a whole, and its potential for reform. However, he also argues a need for greater attention to various obstacles that might prevent such education, and that this could be given more attention by Biesta. Santoro and Rocha (2015) also point to tensions between Biesta’s more existential and institutional understandings of the role of the teacher; the former seems to imply an openness about teaching occurring in the absence of the person of a ‘teacher’ (but as a result of engagement in the environment, for example), while the latter seems to foreground the significance of learning occurring through engagement with the ‘other’. Santoro and Rocha (2015) also gesture towards the need to take greater account of context under circumstances in which moral judgement (as a necessary resource in Biesta’s oeuvre) is called upon.

Notions of the ‘risk’ of education have also been advocated more recently in relation to a variety of educational practices. This includes support for more ‘alternative’ educational experiences, such as those promoted by Marsden (2021) in his recent memoir and call for students to Take Risks. Indeed, such risk taking is itself exemplified through Marsden’s establishment of two schools, ‘Alice Miller’, and perhaps most famously, ‘Candlebark’, as environments in which a more holistic conception of learning can be cultivated. These are sites in which the arts are actively and strongly supported and in which more rigid authoritarianism is replaced by an environment that promotes students’ active engagement in learning and students’ emergence into the world (Miller, 2018). At ‘Candlebark’, set in 1100 acres north of Melbourne, there is a strong focus upon inquiry approaches in all aspects of the curriculum, with ongoing engagement in the local physical environment. In such settings, emphasis upon not just the natural environment but also drama, and quality literature, help to build empathy and compassion (Saunders & Ewing, 2022). Indeed, drama can be used to teach language and literature in a ‘drama-rich pedagogy’ (Saunders, 2022). This can involve reading parts of a text and using drama-based strategies to explore the gaps, silences and critical moments in the text. Such an approach involves delving deeper into the concepts informing the text, resulting in much deeper engagement than had students simply read through the text on its own. Within the paradigm of more conservative, test- and metric-focused approaches to educational provision, such approaches can be understood as inherently ‘risky’ undertakings. However, such experiences and environments serve as sites where students come to know and learn through having the confidence to participate in a range of activities—any number of which may reveal considerable difficulties, challenges, inconsistencies and hesitancies—all necessary to cultivate confidence, resilience and more long-term/embedded understanding.

Accountability, datafication and governance: ‘Anti-risk’ strategies in education

Often, rather than focusing on the potential of risk as an educative vehicle, the question of risk is rearticulated into one of trust in teachers and whether teachers can be trusted to make the judgements and decisions that necessarily guide education provision. This ‘erosion of trust’ in teachers (Daliri et al., 2021) can lead to their demoralization and devaluing—and indeed, the very ‘disappearance’ of the teacher as their work becomes increasingly micro-managed, particularly via various reified forms of student evaluation data (Daliri & Hardy, 2021).

This evisceration of risk is also the focus of the recent volume 2021 World Yearbook of Education which reflects upon just how challenging such a ‘risky’ approach to learning actually is under current, dominant policy conditions. The focus, and subtitle, of this yearbook—Accountability and Datafication in Education—reflect how education policy is currently dominated by concerns about accountability, and how increased attention to the datafication of education fosters more reductive conceptions of accountability. This focus on accountability has emerged from earlier trends towards new public management, and the rise of various kinds of high stakes standardized tests in the 1980s and 1990s. This emphasis upon standardised testing extended further since the 2000s with the development of various international comparative assessments. Such assessments, in conjunction with national testing regimes, facilitated the rise and development of myriad datafication processes (Grek et al., 2021). The increased emphasis upon data is framed as important for evidencing teachers’ decision-making, which cannot simply be left to teacher judgment. The implication is that such judgment is too ‘risk-laden’ and needs to be rearticulated to a focus upon ‘outputs’ understood as test results, so as to better ‘manage’ the ‘inputs’ into education.

Reflecting the focus on outcomes as evidence of performance, Grek et al. (2021) argue contemporary forms of accountability are more accurately described as performance based accountability (PBA), and entail a variety of processes oriented towards the attainment of specific outcomes/performances/measures. Such accountability is based on formal institutional mechanisms but also on processes of datafication, that is, various kinds of typically quantified data associated with standardized tests and other forms of indicators of comparison and evaluation (Grek et al., 2021). Such datafication has also been associated with the digitalization of information, itself emanating from the development of statistical apparatuses during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as part of the ‘machinery of government’ (Rose, 1999, p. 213). Datafication processes are further facilitated by an array of data infrastructures and devices across public and private sectors that aim to ‘capture’ evidence of learning (Williamson et al., 2020).

Under these circumstances, intensive quantification constitutes a form of ‘metric power’ which influences, arguably determines, what is construed as possible (Beer, 2016). Such data and metrics ‘set limits on what can be known and what can be knowable’ (Williamson et al., 2020, p. 352). These measurements represent a classificatory scheme which prioritises certain forms of evidence of learning, whilst diminishing others. In this calibration, those modes of learning that are more readily able to be measured become dominant, and alternative ways of understanding education become marginalised. More ‘risky’ conceptions of education that depend upon uncertainty, judgment and precarity ‘within the moment’ are less able to be recognised and valued. The result is what Williamson et al. (2020) refer to as an ‘intensification of measurement’ (p. 353). This results in a validation and reification of teaching and learning processes seen as leading to enhanced test results, and a diminution of learning associated with more ‘risky’ alternatives.

Despite its aspirations towards ‘managing’ education, governance through data as numbers is ambiguous, relying as it does on a decontextualised understanding of schooling, ‘on being removed from the complex living texture of the world’ (Piattoeva & Boden, 2020, p. 14). Such decontextualized learning is influenced by the broader policy conditions within which practice unfolds. In relation to schooling, these policy conditions have become increasingly influenced by what Savage (2021) describes as ‘alignment thinking’. Such alignment thinking involves ‘harmonising’ and ‘ordering’ educational processes through various kinds of standards reforms. Such approaches also emphasise evidence-based practices, and the generation of data and accountability infrastructures, alongside efforts to unify policy and governance processes. Local and subnational differences are glossed over, with attention given instead to standards-based reforms, evidence-based approaches, increased centralisation (particularly at the national level), ‘harmonisation’ of policy processes, and accountability systems. These accountability systems foreground national and international data and ‘common practices’ rather than context-relevant foci. On this basis, alignment thinking emphasises order, even as such order is always out of reach (Savage, 2021).

This allure of order (Mehta, 2013) results in educational processes that foreground quick-fix, ‘what works’ approaches, even as such efforts invariably fail to deliver the sorts of reforms they promise. As a ‘global form’ of technical rationality, such alignment thinking also cultivates standardized governance processes across contexts (Savage, 2021). These standardized processes are all part of a broader global policy field in which the local, national and global are intricately imbricated (Lingard, 2021).

The Data: Analysing Australian schooling policy

The research presented in this article is drawn from the principal public education authority in Australia of the previous coalition government, the federal Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment, and the current (since May 2022) Labor government’s Department of Education, and associated statutory authorities. It is important to note that in the federal government system of Australia, education is the constitutional responsibility of the individual states. However, attention is given to federal government policies and artefacts in this article because it has an important, albeit indirect, influence upon education. This includes through provision of additional funding to address what it considers to be important priorities for the country as a whole. In a broader Australian context of increasing policy alignment, there have also been increased efforts to encourage more ‘national’ reform of curriculum, teaching and assessment (Savage & O’Connor, 2019). This push for such national reform is often underpinned by concerns that the Australian federation leads to policy reforms that lack coherence and consistency, resulting in failure to deliver quality and equitable outcomes (Keating, 2009). As a result, a more ‘national’ approach to education has become evident through the development of the Australian Curriculum, and the National Assessment Program. (The latter includes a focus upon literacy and numeracy assessment through the National Assessment Program-Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN)). This more ‘national’ approach is also evident in the development of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (ASPST; supported by the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL)). Finally, the National Schools Interoperability Framework is designed to harmonise data collection across systems, and the Measurement Framework for Schooling, identifies key performance metrics against which states are required to report.

At the same time, this ‘national’ character is complex. The ‘national’ character of teaching standards hides how they are also the heterogeneous result of transnational influences (such as the OECD) as well as sub-national entities (e.g., states in the Australian context) (Savage & Lewis, 2018). In relation to curriculum, this more national character can also lead to confusing messages about whether state or federal educational authorities are responsible for reforms in particular areas. Such complexity reflects various asymmetries and polysemous relations between states and the federal government (Savage, 2016). Federal statutory authorities such as the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), which are responsible for the development of national teaching standards, and the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), responsible for the Australian Curriculum and national testing (most notably, NAPLAN), are able to exert considerable influence. This is the case even as reforms supported by such bodies may be reflective of international influences (e.g., OECD), and may be contested at the state level (Savage, 2021). The latter contestation is on display during Education Ministers’ Meetings, when federal and state Education Ministers meet together to negotiate specific schooling reforms and policies. Other bodies, such as the Productivity Commission, the Australian government’s key review and advisory board focused on economic policy and regulation (as well a range of other social and environmental issues), is another entity that influences education provision through its various reports. These reports are drawn upon heavily by governments in making decisions about policy reform.

Consequently, the data informing the analysis presented draw upon key federal websites and associated websites (of ACARA and the Productivity Commission) as authoritative public sources about public provision of federal education policy in the past two years. By way of comparison and contrast, the research also draws upon key international education policies—particularly those espoused by OECD and UNESCO—to help situate these Australian policies within a broader global context. Key international policies were selected which reflected the values of these organisations and that are most current and influential in education. Key policies and associated policy artefacts drawn upon within the research are summarised in Table 1.

Analytically, the paper adopts a broadly critical policy sociology analysis approach (Ball, 2015), involving drawing upon key theoretical concepts—particularly Biesta’s notion of ‘risk’—to critique the nature of these policy foci. Such an approach involves simultaneous processes of both induction and deduction to reveal key insights and themes (Miles et al., 2019). Processes of deduction involved drawing upon notions of risk in relation to how education is discursively framed within key Australian (and international) schooling policies. This analysis simultaneously involved inductively delineating dominant themes evident within these key policy texts. This latter process revealed considerable attention at the federal policy level to more economic and managerial issues (in terms of measurement of performance), with considerably less attention to more social and humanistic concerns. Such an approach also gestures towards interpretive and discursive analytical approaches that seek to highlight the agentic potential within these policies, as well as the broader social conditions that discursively frame and influence what can be construed as possible (Ball, 2015).

While Australian schooling remains the principal policy responsibility of the individual states, an analysis of recent federal government educational policy texts and associated artefacts reflect a variety of competing discourses at play. Arguably, these competing discourses exert influence upon state-based policy-making, particularly within an increasingly ‘nationally’ oriented policy space (Savage, 2021).

Findings: Australian schooling policy—multiple texts, multiple discourses

‘National’ policy foci

At the federal level, within the Australian context, education was explicitly portrayed by the previous Australian coalition (Liberal-National) federal government as intimately associated/connected with issues of employment and economic parameters. This was evident from the way in which education was ‘aligned’ with skills and employment within the previous Department of Education, Skills and Employment. The opening/overarching statement introducing the work of the Department reflects this link between education and the economy:

The Department of Education, Skills and Employment works to ensure Australians can experience the wellbeing and economic benefits that quality education, skills and employment provide (DESE, 2021a).

These more economically oriented discourses, with their emphasis upon specific, measurable outcomes, contrast with the forms of ‘weak’, ‘riskier’ education as a vehicle to foster openness, complexity and unpredictability (Christensen et al., 2021). Within such policies, the focus was upon adequate attention to how schooling can better ensure economic growth and productivity; these are eminently measurable entities as part of the machinery of government (Rose, 1999).

Within a broader policy and political context which drew heavily upon key economic entities, there was also more concern about how to develop immediate skills and workforce development. This was evident in the government’s attention to the work of the Productivity Commission which sought to provide advice about education provision, such as the 2021 inquiry into skills and workforce development (National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development Review: Productivity Commission Study Report (Productivity Commission, 2021)). Under these conditions, the conflation of notions of education, skills and employment gestured towards a broader neoliberal economistic discourse (Springer et al., 2016) in which education was construed as the handmaiden of skills development and employment more generally. Again, under these circumstances, the development of open-ended, ‘riskier’ inquiry experiences (cf. Saunders, 2022), were marginalised.

The current (Labor) administration has separated the former larger Department into the Department of Education, and the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations. Discursively, such separation seems to signify something of a separation between more utilitarian employment and workplace relations, and education more broadly. However, and reflecting continuity in policy provision and development as well as difference, the current government continues to draw upon the resources and perspective of more economic entities such the Productivity Commission. This includes the recently completed Review of the National School Reform Agreement: Study Report (Productivity Commission, 2023) and the ongoing Early Childhood Education and Care inquiry.

Within both the Coalition and Labor ‘schooling’ websites, a separate ‘schools’ tab includes information about an ‘Education strategy for schools’—with other tabs relating to funding, administration and reporting requirements. Such reporting requirements resonate with more measurable, accountability-oriented influences impacting upon schooling more broadly (Grek et al., 2021). This more risk-averse strategy is complemented by provision of a range of information directed at school teachers (including in relation to the Australian school curriculum), effective classroom teaching and leadership practices, and information to assist teachers working in very remote areas (DESE, 2021b; DESE, 2021c; DoE, 2022). And within this education strategy, which seems to serve as the principal information about the educative aspects of the federal government’s involvement in schooling, the list of initiatives foregrounds a very particular set of domains that are characterized as important, at the federal level. This list is almost identical across both the former and current governments. Specifically, these areas relate to:

-

School assessments in Australia (particularly the National Assessment Program);

-

School funding legislation;

-

Explore the Australian Curriculum;

-

Indigenous education targets to help Close the Gap;

-

Disability support programs;

-

Resources for schools;

-

Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration;

-

National School Reform Agreement;

-

Advancing national education priorities (DESE, 2021c).

Within the current Department of Education website, the only additional domain is ‘Engaged classrooms: supporting all students to achieve’.

This eclectic list reflects areas in which the Australian Government, of both political persuasions, has sought to exert influence upon the individual states. Many of these initiatives are regularly (at least annually) evaluated via specific measurable outcomes. Again, reflecting more performance-based accountabilities (Grek et al., 2021), and managerial practices more broadly (Klikauer, 2015), this includes an emphasis upon keeping track of national literacy and numeracy outcomes. This occurs via National Assessment Program-Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN). At the same time, there is also provision of additional funding to schools, the development of a national curriculum, as well as specific concerns about disability support, resourcing for schools more generally, arrangements between the state and federal government through various national school reform agreements, and multiple national education priorities. And the focus on Indigenous education explicitly emphasises measurable outcomes—metrics (Beer, 2016)—with its explicit ‘gap talk’ (‘help Close the Gap’). Concerns about ‘riskier’ forms of learning are unrecognisable within these resource and outcomes-oriented discourses.

Out of this list of initiatives, issues of school assessment—how to measure performance and various federal educational priorities—are given particular attention. A range of National School Reform Agreements have also been signed with states to enable this attention to measuring performance/outcomes/priorities. The Measurement Framework for Schooling in Australia 2020 (ACARA, 2023) is a key policy statement. Explicitly reflecting more managerial practices (Klikauer, 2015), the recent iteration of this initiative outlines ‘nationally agreed KPMs [Key Performance Measures] for schooling’ (p. 4) for the 2020–2023 reporting period. Within this initiative, the National Assessment Program is framed as ‘a major component of the Measurement Framework and encompasses all national assessments approved by education ministers’ (p. 6). This articulates with the Australian federal education system whereby education is the prerogative of the individual states and territories, even as the federal government seeks to exert influence (primarily through its ability to provide additional funding for education). The assessments are described as:

-

annual literacy and numeracy tests (NAPLAN) for Years 3, 5, 7 and 9;

-

sample assessments in Civics and Citizenship, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Literacy and Science Literacy for Years 6 and 10 conducted on a three year cycle;

-

Australia’s participation in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) (p. 6).

Such foci set limits on what is focused upon (Williamson et al., 2020), emphasising the valuing of standardised literacy and numeracy testing. These foci are key contributors to the increased datafication of education more broadly (Grek et al., 2021), and examples of more managerial/efficiency oriented (Klikauer, 2015) ‘anti-risk’ strategies.

There is also further explication of the National Assessment Program, with its emphasis upon Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN):

National minimum standards for literacy and numeracy are defined for assessments in Reading, Writing and Numeracy at each year level. The national minimum standard for each year level is defined and located on a common underlying NAPLAN scale. Students achieving at the minimum standard have typically demonstrated only the basic elements of literacy and numeracy for their year level (p. 6).

This is followed by elaboration of the three key international sample assessments in which Australia participates—PISA, TIMSS and PIRLS (see ‘International influences’ section below). Again, the attention to these initiatives reflect not just the interplay between national and global testing practices (Lingard, 2021) but also how such assessments occupy considerable discursive space. This dominance minimises opportunities for more open-ended applications and inquiries, including cultivating empathy and compassion (Saunders & Ewing, 2022).

In terms of other federal priorities, there is specific reference to the Education Ministers Meeting—the joint meeting of Australian, State and Territory government ministers responsible for education. National education priorities within this meeting (for 2021) included the development of National School Reform Agreement initiatives associated with the development of a unique student identifier for each student, online assessment, progressing national priorities in relation to NAPLAN results and reform of the Australian Curriculum, and access to preschool education:

-

Progressing National Policy Initiatives under the current National School Reform Agreement, including meeting 2021 milestones:

-

o

Unique Student Identifier

-

o

Online Formative Assessment

-

o

-

Progressing priority national school education initiatives, with a focus on the National Assessment Program-Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) and review of the Australian Curriculum

-

Progressing decisions about future preschool education arrangements following consideration of the review of the Universal Access National Partnership (DESE, 2021d).

Again, such foci seek to reduce the ‘risk’ of education (Biesta, 2016) and reflect very specific, technicist, efficiency-oriented approaches to educational provision. The promotion of unique student identifiers, for example, reflect a managerial technology (Klikauer, 2015) designed to ‘capture’, ‘compartmentalise’—indeed ‘manage’—education provision. The use of NAPLAN to make decisions about education provision between the states and federal government also delimits what is construed as valid and valuable education and presents as an obstacle (Yosef-Hassidim (2016) to the sorts of risky education Biesta (2016) seeks to foster. Such numbers are construed as important for their ability to reflect attainment of specific learning initiatives in which students have engaged. These numbers, reflective of the intensification of measurement (Williamson et al., 2020), seek to rationally manage educational provision, reducing education to a number (cf. Hardy, 2022).

The review of the Australian Curriculum—another national priority within the ACARA remit—further characterizes the push to manage and monitor schooling practices (Hardy, 2017). Ongoing reviews of curricula reflect the low thresholds for risk that characterize schooling in Australia. This is evident in commentary by former Education Minister, Alan Tudge, who was concerned that schools ensured they conveyed ‘a positive, optimistic view of Australian history’ and that ANZAC Day should be ‘presented as the most sacred of all days in Australia’ rather than as ‘contested’ (Visontay, & Hurst, 2021). Such a response reflects not only the politics surrounding education provision in Australia, including as a tactic to assist the coalition government’s re-election efforts at the time (Barnes, 2021), but also the broader discourse of ‘control’ and risk-mitigation that surrounds educational provision in schooling more generally. Subsequent criticisms from State Education Ministers of comments about students being taught a ‘negative view of our history’ (Visontay, & Hurst, 2021), potentially leading to an unwillingness for students to later defend Australia, also reflect something of a challenge to efforts to ‘harmonise’ educational provision more broadly in the Australian political system in relation to education (Savage, 2021).

In contrast, and also at the federal policy level, the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration (Education Council, 2019) seeks to adopt a more inclusive and risk-responsive approach. The preamble of the Mparntwe Declaration places students at the centre, reinforcing the transformative potential of education. The preamble refers to participation in the economy and educational outcomes, reflecting advocacy for ‘pedagogies of the possible’ and creative learning experiences characterised by open-endedness, non-linearity, pluri-perspectivism, and a future orientation (Beghetto & Glăveanu, 2022). At the same time, the Mparntwe Declaration also elaborates concerns about societal contribution, and broader aspects of wellbeing and transformation (cf. Saunders & Ewing, 2022):

Young Australians are at the centre of the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration.

Education has the power to transform lives. It supports young people to realise their potential by providing skills they need to participate in the economy and in society, and contributing to every aspect of their wellbeing.

This Declaration sets out our vision for education in Australia and our commitment to improving educational outcomes for young Australians (Education Council, 2019, p. 3).

The Declaration foregrounds (in bold text in the preamble) attention to students’ holistic development in an open and expansionary manner:

Our vision is for a world class education system that encourages and supports every student to be the very best they can be, no matter where they live or what kind of learning challenges they may face (Education Council, 2019, p. 3; emphasis original).

Mention is made of the importance of early learning opportunities, and that ‘To achieve excellence, and for our system to be equitable, every student must develop strong literacy and numeracy skills in their earliest years of schooling’ but also that they must ‘go on to develop broad and deep knowledge across a range of curriculum areas’ (p. 3). Again, there is evidence of what can be understood as a ‘riskier’ approach to education (Biesta, 2016). This is evident in advocacy for an approach to education beyond constrained and narrow conceptions of literacy and numeracy as captured in standardized metrics, and greater recognition of the actual circumstances of students’ lives (Beghetto & Glăveanu, 2022).

Importantly, there is explicit recognition that the ‘metric power’ (Beer, 2016) of literacy and numeracy skills and knowledge are not sufficient, and that broader social, emotional, spiritual and aesthetic development and wellbeing of young Australians are crucial. This includes developing flexibility and being responsive to societal challenges, alongside developing a more individual sense of resilience and wellbeing:

However, our education system must do more than this – it must also prepare young people to thrive in a time of rapid social and technological change, and complex environmental, social and economic challenges. Education plays a vital role in promoting the intellectual, physical, social, emotional, moral, spiritual and aesthetic development and wellbeing of young Australians, and in ensuring the nation’s ongoing economic prosperity and social cohesion. They need to deal with information abundance, and navigate questions of trust and authenticity. They need flexibility, resilience, creativity, and the ability and drive to keep on learning throughout their lives (p. 3).

However, how such a more expansionary focus, with all its attendant uncertainties, sits in relation to other policy initiatives and pressures at the federal level, is very much open for debate. An analysis that advocates for a ‘risky’ approach to Australian schooling policy as inherently educational is novel in recent schooling policy studies.

International influences

Both more ‘standardized’ and compartmentalised approaches to learning are similarly reflected in broader international policies, which simultaneously seek to influence Australian schooling policy. Reflecting the imbrication of the national with the global (Lingard, 2021), more economistic and managerial foci, alongside some consideration of more social and humanistic issues, are evident in global policies. This is evident within the OECD’s ubiquitous annual Education at a Glance reports, which seek to exert influence nationally. These reports display evidence of the metricisation of the social (Beer, 2016) in how they bring together a range of indicators to reflect the nature and status of education at present around the world. The forward to the 2021 volume reflects more economistic and neoliberal logics (Springer et al., 2016), including concerns about efficiency (cf. Klikauer, 2015), and the way such logics are intricately imbricated with education:

Governments are increasingly looking to international comparisons of education opportunities and outcomes as they develop policies to enhance individuals’ social and economic prospects, provide incentives for greater efficiency in schooling, and help to mobilise resources to meet rising demands. The OECD Directorate for Education and Skills contributes to these efforts by developing and analysing the quantitative, internationally comparable indicators that it publishes annually in Education at a Glance. Together with OECD country policy reviews, these indicators can be used to assist governments in building more effective and equitable education systems (OECD, 2021, p. 3).

Given that so many of these indicators in education are associated with standardized (PISA) tests supported by the OECD, the comparisons advocated are more in keeping with data-centric conceptions of education (Grek et al., 2021), and an ‘outcomes’ approach to education, rather than ‘riskier’ conceptions (Biesta, 2016).

However, and at the same time, the international education policy space is also characterized by support for a richer conception of educational practice. Much greater emphasis upon ‘riskier’ notions of openness and unpredictability (Christensen et al., 2021) are evident in support for sustainable learning. This is perhaps most evident in the UNESCO Sustainable Development Goals, and particularly Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all (UNESCO, 2021). The Education 2030 Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4 provides a rich conception of education, within a broader global space, and is explicitly oriented towards ensuring the provision of educational opportunities for all. Within the Declaration, a more holistic, aspirational and inclusive approach was key:

Our vision is to transform lives through education, recognizing the important role of education as a main driver of development and in achieving the other proposed SDGs. We commit with a sense of urgency to a single, renewed education agenda that is holistic, ambitious and aspirational, leaving no one behind. This new vision is fully captured by the proposed SDG 4 ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’ and its corresponding targets (UNESCO, 2015, p. 7).

Such an aspirational endeavour is inherently ‘risky’ (Biesta, 2016) and presents as an initiative seen as developing out of and extending earlier goals inspired by a broader humanistic vision of education and development:

It is transformative and universal, …. It is inspired by a humanistic vision of education and development based on human rights and dignity; social justice; inclusion; protection; cultural, linguistic and ethnic diversity; and shared responsibility and accountability (UNESCO, 2015, p. 7).

More reflective of engagement with ‘the complex living texture of the world’ (Piattoeva & Boden, 2020, p. 14), this broader plethora of concerns, including advocacy for a more socially-conscious awareness, is more in keeping with a broader conception of education. This is one that is willing to be more open—to take more risks (Biesta, 2016)—to try to effect the sorts of human rights, social justice, inclusion and protections so necessary in the wider world. This Declaration reinforced education as a public good and as crucial for fostering stability and sustainability as well as employment and poverty reduction.

Discussion and conclusion: Australian schooling policy as a ‘risky’ proposition

From the outset of the former Australian federal coalition government’s overview of education on its principal website, the conflation between the economy and education foregrounded a more economistic, managerial and transactional approach to education. While mention was made of wellbeing, it was the economic benefits that seemed most overt, alongside efforts to ‘manage’ education to ensure prescribed outcomes were being achieved. This reflects how economic and managerial discourses dominate at the federal level. While the current Labor government has sought to explicitly break this nexus between education and economy—most overtly evident in the establishment of two distinct departments (Department of Education, and Department of Employment and Workplace Relations)—continuity in policy provision has ensured continuation of more reductive approaches to education. Such continuity is most evident in relation to the range of ‘measures’ and evaluations that underpin agreements between the federal government and the states; this evaluative approach reflects a broader context characterised by a push to reform education and ensure greater ‘national’ consistency (Savage, 2021).

While the broader foci of the Mparntwe Declaration and UN SDG4 goals gesture toward a ‘riskier’ conception of education, the federal policy ecology within which such initiatives are located in the Australian schooling context suggests this work may be challenging. The overarching OECD policy framework provides a broader set of global policy conditions that have exerted strong influence and that mitigate against more localized policy concerns; this is very much evidence of the global ‘imbricating’ in relation to the national (and local) (Lingard, 2021). The high profile Education at a Glance reports serve a significant discursive purpose by overtly articulating the value and importance of various kinds of international comparisons which are construed as necessary to enhance individuals’ social and economic prospects and improve the efficiency of schooling (OECD, 2021). The foregrounding of ‘individuals’ in this context is also significant and reflective of broader neoliberal discourses (cf. Springer et al., 2016) that compete with the more humanistic aims of UNESCO. The latter are framed as inherently equitable –seeking to be ‘holistic, ambitious and aspirational, leaving no one behind’ (UNESCO, 2015, p. 7). The push for more inclusive and equitable education that supports ‘lifelong learning opportunities for all' (UNESCO, 2015, p. 7) challenges the more individualistic, ‘efficient’ and resource-intensive approaches associated with the OECD (2021). The way in which the OECD (2021) contributes to such work through its focus upon various quantitative, internationally comparable indicators also foregrounds the influence of metrics more broadly (Beer, 2016) and the way in which quantitative markers of achievement set limits upon what is construed as valid evidence of learning (Williamson et al., (2020). The decontextualisation and removal from the complexity of the actually living world (Piattoeva & Boden, 2020) is glossed over and given little consideration within a broader context of concern about Australia’s competitiveness. This competitiveness positions Australia in an international/global context in which such metrics are taken as indicators of current educational capacity and as proxies for future economic competitiveness. The reliance upon the more economistic emphases of the Productivity Commission at the national policy level represent a complementary logic to that of the OECD. As a consequence, there is reduced scope for the development of a more inclusive, socially-constructive ‘riskier’ conception of education.

Such economistic and atomistic managerial conceptions of schooling are further reinforced through attention to various ‘nationally agreed KPMs for schooling’ (p. 4) within ACARA’s The Measurement Framework for Schooling in Australia 2020 (ACARA, 2023). As a key part of the national infrastructure/architecture of schooling in Australia, the more measurement-oriented discourses within such policy artefacts serve to limit the scope for a more expansive—‘riskier’—conception of learning. Similarly, ongoing reviews of curriculum also reflect concerns to manage and monitor (Hardy, 2017) educational provision in ways that mitigate against the sorts of ‘riskier’ dialogues essential to actual educative processes (Biesta, 2016).

Various kinds of harmonisation are also evident in explicit attention given to the development of a ‘Unique Student Identifier’ for students as part of a broader architecture to manage and monitor schooling (Hardy, 2017). Advocacy for such a number, alongside such technologies as the national literacy and numeracy assessment (NAPLAN), reflect the myriad datafication processes that have characterized recent reforms in education provision more generally (Grek et al., 2021). Attention to such numbers represent the push for precision and ‘exactness’ and the importance associated with the ability to ascribe numeric evidence of learning achievement and attainment to particular students. The ongoing focus upon NAPLAN points to the continued influence of National School Reform Agreements between the states and federal government to continually monitor student outcomes in the form of such tests. Attention to these tests reflects a continued desire to ensure education provision is carefully scrutinised via standardized data as evidence of student learning, leading to similar reification and collection of associated data in schools (Daliri & Hardy, 2021). Such approaches do little to address the overall ‘erosion of trust’ in teachers more generally (Daliri et al., 2021). These metrics form part of a broader array of curriculum, teaching and assessment practices that characterize school reform within what can be construed as ‘an era of standardization’ (Hardy, 2021).

The implications of this research are that as more attention is given to more economistic influences and seeking to identify and control various technologies of governance (Rose, 1999), education will become more risk averse. Policy-makers need to engage with education in broader terms to develop the sorts of capacities necessary to be responsive to current challenges that beset education and society more broadly, including developing the resilience needed to address young people’s mental health during precarious economic times (Goodwin et al., 2020; Irvine & Rose, 2022; Meherali et al., 2021). Much greater attention needs to be given to learning contexts as necessarily open-ended and not amenable to measuring and monitoring specific outcomes of student performance as markers of achievement—to learning as ‘risky’. Various statistics and measures of performance/attainment are construed as readily ‘manipulable’, representing as they do, simplified approximations of students’ ‘learning’. However, education cannot be so readily ‘fixed’ (Biesta, 2016). As Biesta (2016) argues, while education can be made ‘to work’, such an approach fails to acknowledge the broader purposes of education, or at best, residualises such purposes to a reductive conception of learning that can typically be ‘measured’, ‘monitored’ and ‘managed’ (Hardy, 2017). Efforts to try to ‘secure’, ‘strong’ and ‘risk-free’ education is a manifestation of a desire to ensure perfect coherence between the ‘inputs’ and ‘outputs’ of education rather than recognition of the necessary instability of genuine learning; this includes learning for empathetic and compassionate ends (Saunders & Ewing, 2022).

Through institutions of government, educational policy can actively promote and materially support more open, creative, inclusive and sustainable educational practices—in short, more open-ended, ‘risky’ approaches to education (Biesta, 2016). However, whether and how current Australian federal schooling policy enables such practices is questionable, given the dominance of more economistic and managerial foci. Biesta (2016) argues that educational approaches and institutions have limited the complexity of learning. Such simplification is unlikely to foster the sorts of reform to enable genuinely educational experiences to become common-place. The challenge for institutionalized education in the form of schooling policy, particularly within a federal structure such as that in Australia, is how to promote the sorts of risk-taking that could benefit schooling. This needs to occur in ways that build upon and foster more educational opportunities within the states responsible for the actual delivery of schooling. To do otherwise can be understood as a ‘truly’ risky proposition—to fail to draw sufficiently upon notions of risk as a resource to inform educational provision. Current policy discourses indicate there is much more to be done if we are to realize ‘the beautiful risk of education’ (Biesta, 2016).

Data availability

All data are publicly available.

References

ACARA. (2023). The Measurement Framework for Schooling in Australia 2020. Australian Government.

Alice Miller (2018). Alice Miller. https://www.alicemillerschool.com/aboutus/

Australian Government (2020). Unique Student Identifier. Australian Government. https://www.usi.gov.au/

Ball, S. (2015). What is policy? 21 years later: reflections on the possibilities of policy research. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(3), 306–313.

Barnes, N. (2021). Why Alan Tudge is now on the history warpath. Downloaded 30 October 2021: https://www.aare.edu.au/blog/?p=10987

Beghetto, R. (2018). Beautiful risks: Having the courage to teach and learn creatively. Rowman & Littlefield.

Beghetto, R., & Glăveanu, V. (2022). The beautiful risk of moving toward pedagogies of the possible. In R. Sternberg, et al. (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of transformational giftedness for edcuation (pp. 23–42). Palgrave Macmillan.

Biesta, G. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Paradigm Publishers.

Biesta, G. (2016). The beautiful risk of education. Routledge.

Christensen, J., Ekelund, N., Melin, M., & Widén, P. (2021). The beautiful risk of collaborative and interdisciplinary research: A challenging collaborative and critical approach toward sustainable learning processes in academic profession. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094723

Daliri, R., & Hardy, I. (2021). The devalued, demoralized and disappearing teacher: The nature and effects of datafication and performativity in schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 30(102), 1–22.

Daliri, R., Hardy, I., & Creagh, S. (2021). Data, performativity and the erosion of trust in teachers. Cambridge Journal of Education, 52(3), 391–407.

Department of Education (DoE). (2022). Australian Government: Department of Education. https://www.education.gov.au/

Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE). (2021a). Australian Government: Department of Education, Skills and Employment. Australian Government. https://www.dese.gov.au/

Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE). (2021b). Schooling. Australian Government. https://www.dese.gov.au/schooling

Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE). (2021c). Education Strategy for Schools. Australian Government. https://www.dese.gov.au/schooling/education-strategy-schools

Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE). (2021d). Education Ministers Meeting. Australian Government. https://www.dese.gov.au/education-ministers-meeting

Education Council. (2019). Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration. Education Council.

Fishhoff, B., Watson, S., & Hope, C. (1984). Defining risk. Policy Sciences, 17, 123–139.

Goodwin, R., Weinberger, A., Kim, J., Wu, M., & Galea, S. (2020). Trends in anxiety among young adults in the United States 2008–2018: Rapid increases among young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 130, 441–446.

Grek, S., Maroy, C., & Verger, A. (2021). Introduction – Accountability and datafication in education: Historical, transnational and conceptual perspectives. In S. Grek, C. Maroy, & A. Verger (Eds.), World Yearbook of Education 2021: Accountability and Datafication in the Governance of Education (pp. 1–22). Routledge.

Hardy, I. (2017). Measuring, monitoring, and managing for productive learning? Australian insights into the enumeration of education. Revista De La Asociación De Sociología De La Educación (RASE), 10(2), 192–208.

Hardy, I. (2021). School reform in an era of standardization: Authentic accountabilities. Routledge.

Hardy, I. (2022). Affective learning for effective learning? Data, numbers and teachers’ learning. Teaching and Teacher Education. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103754

Irvine, A., & Rose, N. (2022). How does precarious employment affect mental health? A scoping review and thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence from western economies. Work Employment and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170221128

Keating, J. (2009). A new federalism in Australian education: A proposal for a national reform agenda. Education Foundation.

Klikauer, T. (2015). What is managerialism? Critical Sociology, 41(7–8), 1103–1119.

Lingard, B. (2021). Globalisation and education: Theorising and researching changing imbrications in education policy. In B. Lingard (Ed.), Globalisation and education: Theorising and researching changing imbrications in education policy (pp. 1–27). Routledge.

Loughland, T., & Clifton, J., et al. (2023). It’s a horror movie right there on my computer screen: The beautiful risk of work-integrated learning. In M. Winslade (Ed.), Work-integrated learning case studies in teacher education (pp. 365–377). Springer.

Marsden, J. (2021). Take risks: Raising kids who love the adventure of life. Macmillan.

Meherali, S., Punjani, N., Louie-Poon, S., Rahim, K., Das, J., Salam, R., & Lassi, Z. (2021). Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID-19 and past pandemics: A rapid systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073432

Mehta, J. (2013). The allure of order: High hopes, dashed expectations, and the troubled quest to remake American schooling. Oxford University Press.

Miles, M., Huberman, A., & Saldaña, J. (2019). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Sage.

OECD. (2021). Education at a glance 2021: OECD indicators. OECD.

Piattoeva, N., & Boden, R. (2020). Escaping numbers? The ambiguities of the governance of education through data. International Studies in the Sociology of Education, 29(1–2), 1–18.

Productivity Commission. (2021). National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development Review: Productivity Commission Study Report. Australian Government.

Productivity Commission. (2023). Review of the National School Reform Agreement: Study Report. Australian Government.

Rose, N. (1999). Powers of freedom: Reframing political thought. Cambridge University Press.

Santoro, D., & Rocha, S. (2015). Review of Gert J.J. Biesta, the beautiful risk of education. Studies in Philosophy of Education, 34, 413–418.

Saunders, J. (2022). Using drama-rich pedagogies with the episodic pre-text model to improve literacy. Teachers and Curriculum, 22(2), 49–61.

Saunders, J., & Ewing, R. (2022). ‘It lifts up your imagination’: Drama-rich pedagogy, literatur and literacy – The School Drama programme. In M. McAvoy & P. O’Connor (Eds.), The Routledge companion to drama in education (pp. 439–449). Routledge.

Savage, G. (2016). Who’s steering the ship? National curriculum reform and the re-shaping of Australian federalism. Journal of Education Policy, 31(6), 833–850.

Savage, G., & Lewis, S. (2018). The phantom national? Assembling national teaching standards in Australia’s federal system. Journal of Education Policy, 33(1), 118–142.

Savage, G. (2021). The quest for revolution in Australian schooling policy. Routledge.

Savage, G., & O’Connor, K. (2015). National agendas in global times: Curriculum reforms in Australia and the USA since the 1980s. Journal of Education Policy, 30(5), 609–630.

Savage, G., & O’Connor, K. (2019). What’s the problem with ‘policy alignment’? The complexities of national reform in Australia’s federal system. Journal of Education Policy, 34(6), 812–835.

Springer, S., Birch, K., & MacLeavy, J. (2016). An introduction to neoliberalism. In S. Springer, K. Birch, & J. MacLeavy (Eds.), The handbook of neoliberalism (pp. 1–14). Routledge.

Visontay, E. & Hurst, D. (2021). Ham fisted culture wars: States take Alan Tudge to task over history curriculum concerns. The Guardian. Downloaded 30 October 2021: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/oct/22/ham-fisted-culture-wars-states-take-alan-tudge-to-task-over-history-curriculum-concerns

UNESCO. (2015). The Education 2030 Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4. UNESCO.

Williamson, B., Bayne, S., & Shay, S. (2020). The datafication of teaching in higher education: Critical issues and perspectives. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(4), 351–365.

Yosef-Hassidim, D. (2016). Review of The beautiful risk of education. Philosophical Inquiry in Education, 23(2), 222–228.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

There are no competing interests associated with this article, personal, financial or otherwise.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hardy, I. Australian schooling policy: A risky proposition. Aust. Educ. Res. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00711-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00711-6