Abstract

International literature has recognised the importance of education research with Pacific learners. In an Australian context, the early years learning framework for Australia and the Australian curriculum emphasise that education sectors should work towards cultivating respect for cultural diversity and to develop intercultural understanding and intercultural capabilities. As such, the call to better understand the cultural complexities that underpins Pacific learners and their interactions with educational processes remains pertinent. This scoping review offers an important synthesis of empirical research on the educational successes and challenges of Pacific learners in Australian educational settings from 2010 to 2021. While this study offers critical insights for teacher education and research, the findings also revealed paucities in education research with Pacific learners. Thereby, propositions for future and ongoing education research with Pacific learners in Australia are offered in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term ‘Pacific’ (peoples) is a common generalist term that is used to refer to people of Melanesian, and/or Micronesian, and/or Polynesian ancestry (Ministry of Education, 2013). In an Australian context, Kearney and Glen (2017) stated that “individuals representing or seen as representing Pacific peoples have multiple world views and are defined by personal layers of identity influenced by social, cultural, linguistic, spiritual, geographic and economic forces…” (p. 278). While there is a historical contention in literature that examines the use of generalist terms (see Smith, 1998; Grainger, 2006; Enari & Haua, 2021), the authors refer to ‘Pacific learners’ in this article to identify the populations of interest for the purposes of this scoping review. However, the authors do not intend to homogenise the multiple ethnicities, nationalities, genders, languages or cultures that exist within these populations.

Australia is located within the Oceania region which includes the countries and territories of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. In 2016, Australia’s population was at 24 million people (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2016) which included over 300 cultural groups, and over 300 languages that were spoken in the country (ABS, 2017a). The nation’s population that claimed Pacific ancestry were identified via 23 Pacific ancestries across the region (Ravulo, 2015) and they are among the fastest growing populations in Australia. For example, the Australian population increased by 8.8% between 2011 and 2016 (ABS, 2017b), whereas the population of those claiming Pacific ancestry grew by 20.4% between 2011 and 2016, which is on par with the rate of increase in people claiming Chinese ancestry (Batley, 2017). The growth in the Pacific population can be attributed to migration and to those who were born in Australia (Batley, 2017; Faleolo, 2019). However, it is important to note that when reviewing individual ancestries, the count of responses is also the count of people, but the total number of responses does not represent the actual Pacific population in Australia because each person can provide up to two ancestries and multiple responses are encouraged. This measurement issue is explained and documented by the ABS (2021). As shown in Fig. 1, the growth in the number of responses claiming Pacific ancestry continued from 2016 to 2021.

While the Maori population is not included in Fig. 1, it is noted that there was a 19.67% growth in the number of responses claim Maori ancestry from 2016 to 2021. Furthermore, 54.48% of the responses claiming Pacific ancestry in the 2021 Australian census were aged 30 years and younger. This suggests that many from this cohort would either be enrolled within an education sector as a student and/or they might have entered the workforce for the first time. The implications of having a very youthful population profile on the labour market as well as other relevant factors supports the need for more education research with Pacific learners in Australia.

In Australian educational contexts, it is emphasised in the Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (EYLF) and the Australian Curriculum that learners are to be supported to value their own cultures, languages and beliefs, and those of others, as well as to develop an appreciation and respect for the diversity of cultures, races and ethnicities (Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority [ACEQA], 2021; Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2014; Pettitt & Tierney, 2016). Thereby, educators, teachers and school leaders should receive professional training for intercultural education (ICE) and intercultural capabilities (ICC) to support learners to embrace their identity and to develop a sense of belonging in relation to place, ways of knowing and relating to each other and their educators and/or teachers (Comber & Woods, 2018; Ohi et al., 2019; Ponton, 2017). The alternative would be the academic, social and psychological long-term consequences of not belonging and of exclusion (Comber, 2015; Dorling, 2016; Halse, 2018; Rogers, 2011). Conversely, Cloonan et al., (2017) asserted that such curriculum decrees pose challenges for teachers and including ICE in school curriculum documents does not equip teachers with the intercultural knowledge or skills to effectively build students’ intercultural capabilities.

International research has also found that many teachers and school leaders lack the knowledge, skills and confidence to engage with ICE to ensure meaningful intercultural learning among students (Faas et al., 2014; Leeman, 2008; Niemi et al., 2014). However, there is a growing body of international research that recognises and advocates the importance of reducing disparities for Pacific learners in predominantly Western educational settings, which might also support ICE and ICC (e.g. Amituanai-Toloa & McNaughton, 2008; Amituanai-Toloa et al., 2009; Au, 2002; Coxon et al., 2002; Crossley et al., 2017; Fa’avae, 2018; Froiland et al., 2016; Helu-Thaman, 1997; Keehne et al., 2018; Kepa & Manu’atu, 2006; MacDonald & Lipine, 2012; Maebuta, 2011; Manu’atu, 2000; ‘Ofamo’oni & Rowe, 2020; ‘Otunuku et al., 2013; Raturi et al., 2011; Samu, 2010; Smith & Wolfgramm-Foliaki, 2021; Tharp, 1982). Findings have suggested various approaches to support Pacific learners which included an evaluation of teacher education in relation to its contributions to the achievement of Pacific learners (e.g. Airini et al., 2009; Helu-Thaman, 2001); the consideration and the use of Pacific and ethnic specific tools, models, guidelines, and competencies in education, research and in other fields (e.g. Airini et al., 2010; Amituanai-Toloa, 2009; Anae, 2019; Fa’avae, 2019; Kepa & Manu’atu, 2008; Ponton, 2018; Reynolds, 2018; Samu, 2011; Te Ava & Page, 2018; Tualaulelei & McFall-McCaffery, 2019; Vaioleti, 2006); and the development and use of strengths-based approaches in education and research with Pacific learners (e.g. Anae, 2016; Airini et al., 2010; Helu-Thaman, 2007; Pale, 2019; Si’ilata et al., 2019; Te Ava & Rubie-Davies, 2011; Wolfgramm-Foliaki & Smith, 2020). Notably, most of the international education research with Pacific learners are based in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) because historically more research has been conducted there over an extended period of time. For example, Samu (2020) highlights the origins, current status and new directions within Pacific education in NZ. Evidently, international research also supports the need for more education research with Pacific learners in Australia.

The Tongan proverb—takanga ‘enau fohe (used within the title of this article) refers to people working collaboratively and collectively to achieve a task, which is reflective of this scoping review. The authors acknowledge that the work towards understanding Pacific learners in Australian educational settings is ongoing, and that it can be strengthened based on what is known, and what is yet to be explored. Education research with Pacific learners matters in Australia, particularly when there is evidence of growing populations of Pacific communities who reside in states across Australia. It also matters within the field of Pacific education research and its development and progress within Australia and transnationally. For example, the Australian Pasifika Educators Network was recently formed and, among its priorities, they are working towards curriculum and educational policy reform that includes equity, culturally responsive and culturally sustaining pedagogy for Pacific learners in Australia. Therefore, this study is pertinent as it addresses what is known about the educational successes and challenges of Pacific learners in Australia educational settings. This is critical as it contributes to an understanding of what is required to achieve and sustain better educational outcomes for Pacific learners.

Method

For this study, Arksey and O'Malley’s (2005) methodological framework for scoping reviews was adopted to enable replication and to strengthen the rigour of the research. The methodological framework for scoping reviews is organised into five steps which are (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). The process is not linear but iterative, requiring researchers to engage with each stage in a reflexive way and, where necessary, repeat steps to ensure that the literature is covered in a comprehensive way (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

While systematic reviews are designed to answer a specific question about a population, the aim of a scoping review is to map relevant studies, identify how they have been conducted and what they have found. A scoping review therefore provides a “snapshot of a particular topic area” (Booth et al., 2012, p.19) and aims to chart the studies rather than to evaluate (Gore et al., 2017). Grant and Booth (2009) have defined scoping reviews as a “preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature that aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research)” (p. 95). In the field of education, scoping studies have previously been used to better understand what is known and where the research gaps are (e.g. Daza et al., 2021; Fray & Gore, 2018; Gore et al., 2017; Turner & Stough, 2019).

As the first step for conducting this scoping review, the following research question was formulated:

What is known from existing literature about the educational successes and/or challenges of Pacific learners within Australian educational settings?

The second step was to identify relevant studies. The key terms that were used to locate the existing literature were as follows: (Pasifika* OR “Pacific People*” OR “Pacific Islander*” OR Polynesian* OR Melanesian* OR Micronesian*) AND (Education* OR School*) AND (Australia*). Quotation marks were included around “Pacific People*” and “Pacific Islander*” to stop the search returning results with just “people” or “islander”. The inclusion criteria were set prior to the review process and this was based on extant literature that provided empirical evidence on the educational successes and/or challenges of Pacific learners in Australia. The context of the inclusion criteria consisted of extant literature from four (4) education sectors: 1) early childhood, 2) primary, 3) secondary and 4) tertiary; full text available and written in the English language. The literature search was focussed within Australia only and it was conducted through the following electronic databases: A + education (Informit), Education research complete (EBSCOhost), ERIC (EBSCOhost): Education Resource Information Center, ERIC (Proquest) and NCVER research database. These databases had returned relevant extant literature which will be presented in the results section. Next, a screening took place using the abstracts of the extant literature that were deemed relevant to the inclusion criteria. Then, the reference lists and citations from all relevant literature were scanned for any further relevant literature.

The third step involved the study selection explained in the results section. The fourth step consisted of charting the data as shown in Table 1 (see Appendix).

The final step was to collate, summarise and report the data and this will be presented in the results and discussion sections. The following information was extracted from the extant literature: author(s), study location, title and journal/publisher, participants and sample size, data collection method, and a summary of the findings that were relevant to the inclusion criteria. The findings from the extant literature that were considered irrelevant to the inclusion criteria were omitted.

The scoping review methodological approach proposes an optional stage which is a consultation process, and we opted to conduct it. Contributors to the consultation process consisted of two (2) Australian academics who are experts in the fields of teacher education and education research with Pacific learners. The first academic is based in Queensland and the second academic is based in Victoria, Australia. The experts helped to determine if the extant literature identified in this scoping review were relevant to the inclusion criteria and provided recommendations for any additional literature to be included in the scoping review. This consultation process added invaluable insights and context for the scoping review.

Results

A descriptive overview

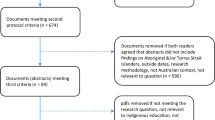

A key step in the scoping review process is ‘charting’ the data (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). The results of the database search are depicted in Fig. 2. Table 1 (see Appendix) presents an overview of the 20 extant literature from 2010 to 2021 that were located from the initial database search for this scoping review and the consultation with the experts. It includes details on the name of the author(s), year of publication, study location, title and journal/publisher, sample size, data collection method, an indication of whether the literature identified educational successes and challenges of Pacific learners in Australia, and the education sector(s) that the studies were conducted in.

As shown in Fig. 2, the initial database search returned 503 results; however, 191 were duplicates, which were subsequently removed. A further 113 were removed as they were older than 2010. A further 127 were removed as the focus was not on Pacific learners in Australia. This left 72 papers for the abstract screening.

At the abstract screening stage, 58 out of 72 results were identified as irrelevant for the purposes of this scoping review and were removed. This left 14 results for the next screening stage. Using the 14 results, the reference lists were scanned, and an additional seven (7) results were identified that might be of relevance, which increased the total to 21 results.

At the next screening stage, three (3) out of the 21 results were identified as irrelevant for this scoping review and were removed. The results that were aligned to the aims of this scoping review was 18 extant literature.

At the final screening stage in consultation with the experts within this field in Australia, a further four (4) out of 18 were removed, which then left 14 relevant extant literature. Then, an additional six (6) were suggested by the contributors to the consultation process. The research team scanned through the six (6) literature and agreed that they were relevant. Therefore, the search and consultation yielded a total number of 20 extant literature that were identified as relevant to the inclusion criteria for this scoping review.

The results as shown in Table 1 (see Appendix) indicate that there were six (6) studies that were co-authored by Judith Kearney; four (4) by Irene Kmudu Paulsen; three (3) were either authored or co-authored by Glenda Stanley; three (3) by Eseta Tualaulelei; two (2) were co-authored by Sue Scull and Michael Cuthill; two (2) by Jioji Ravulo; and two (2) were authored or co-authored by Andrew Fa’avale. The remaining authors had appeared once as an author or co-author.

Interestingly, from 2010 to 2015 there were four (4) extant literature that met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review, and from 2016 to 2021 there were 16. This indicates that in more recent years, there has been an increase in research inquiry into the education of Pacific learners in Australia.

Across Australia, the results also indicate that there were 14 relevant studies that were conducted in Queensland; four (4) in Victoria; and two (2) in New South Wales. It appears that the State of Queensland has led the inquiry into education research with Pacific learners over the past decade in Australia.

Furthermore, the results revealed that 14 extant literature were published in academic peer reviewed journals; three (3) were doctoral theses; two (2) were conference papers; and one (1) was a master’s thesis.

Also shown in Table 1 (see Appendix), most of the studies had implemented a Western qualitative research approach. These included in-depth interviews, semi-structured interviews, informal ethnographic interviews, participant surveys, participant observations, collection of artefacts, field notes, research journals and case studies (e.g. Kearney & Donaghy, 2010; Paulsen, 2018a; Ravulo, 2018; Scull & Cuthill, 2010). The qualitative data analyses included an interpretative phenomenological analysis, underpinned by the principles of phenomenology and hermeneutics, critical ethnography and a thematic analysis (e.g. Fa’avale et al., 2016; Kearney et. al., 2018; Stanley, 2019). Evidently, the results highlighted that there is a development in the consideration and use of Pacific qualitative research approaches that were implemented in a few of the studies (e.g. Fa’avale, 2020; Stanley, 2019; Tualaulelei, 2017).

All the studies (20) that were relevant to this scoping review had identified and/or demonstrated contributing factors for educational successes and/or challenges of Pacific learners in Australian educational settings. This finding will be extrapolated in a thematic overview in the following section.

Lastly, the results indicated that there were 12 studies that had participants from the tertiary sector; 11 from the secondary sector; three (3) from the primary sector; and zero (0) studies that had participants from the early childhood sector. It is important to note that some of these studies had participants from more than one education sector, hence the above figures do not add up to 20 (e.g. Kearney & Glen, 2017; Scull & Cuthill, 2010; Stanley & Kearney, 2017; Ravulo, 2018, 2019; Tualaulelei & Kavanagh, 2015).

A thematic overview

This section is organised thematically by the ‘primary units of analysis’ that underpinned this scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley). This included identifying and extrapolating the contributing factors for educational successes and/or challenges of Pacific learners in Australian educational settings. The thematic overview is presented as follows.

Educational successes

The results of this scoping review revealed the following as contributing factors for educational success for Pacific learners: 1) family support and positive expectations; 2) positive relational connections between learners and teachers; 3) effective collaborative partnerships between the education sector and Pacific communities in Australia. Each of these will be addressed below.

1) Family support and positive expectations.

The results revealed that Pacific learners who have experienced educational success have received support from their families and they also had close and connected relationships (e.g. Kearney & Donaghy, 2010; Paulsen, 2018b). Similarly, learners with high aspirations, a positive self-concept and sufficient in-home and at-school support had more positive educational experiences (e.g. Paulsen, 2016). Research also showed that Pacific peoples have a high regard for education, and they hold high expectations of the education systems to provide the learning experiences required for their children to achieve successful outcomes (see Fa’avale, 2020; Paulsen, 2016; Ravulo, 2018; Stanley & Kearney, 2017).

2) Positive relational connections between learners and teachers/schools.

Relational connections between Pacific learners and their educators, teachers and/or schools were recognised to be contributing factors to educational success (Blackberry & Kearney, 2020). For example, Paulsen (2016) found that secondary schools supported and recognised the unique needs of Pacific learners, and their commitment to addressing their academic and social needs of these learners were deemed critical. Similarly, Ravulo (2019) identified that learners also experienced educational success when staff: exercised culturally appropriate support and understanding; provided opportunities for learners to develop a greater sense of belonging and connection; and created opportunities for learners to engage within a cultural context and offered support to manage conflicting expectations and priorities.

3) Effective collaborative partnerships between the education sector and Pacific communities in Australia.

The results also showed that effective collaborative partnerships between universities, their local communities and other stakeholders can lead to educational success for Pacific learners in Australia (e.g. Cuthill & Scull, 2011). Equity outreach initiatives in schools and transition programs that involved Pacific mentors have contributed to positive educational outcomes as well as supported successful transitions of Pacific learners into tertiary education (see Kearney & Donaghy, 2010; Ravulo, 2018; Tualaulelei & Kavanagh, 2015). Such effective collaborative partnerships between the education sector and Pacific communities are also supported by drawing on Pacific cultural perspectives. For example, the Niu Framework was developed by Fa’avale et al. (2016) to support outreach, student success and retention at the university level in Queensland. This model had implications for how universities can use cultural knowledge systems to support students’ academic identities, performance and success. Moreover, Tualaulelei (2017) theorised that transforming education for Samoan students might involve the consideration of the Pacific concept of vā (relational space) as a ‘structured and structuring’ space that exists between educational stakeholders and communities.

Challenges to achieving educational success

The results from this scoping review also revealed some challenges to achieving educational success for Pacific learners which included 1) lack of access to permanent residency and/or Australian citizenship; 2) other constraints on post-compulsory educational opportunities for the learner; 3) lack of professional learning and development for intercultural understanding (ICU) and intercultural capabilities (ICC). Each of these will be addressed below.

1) Lack of access to permanent residency and/or Australian citizenship.

The results revealed that Pacific learners who lived in Australia without permanent residency and/or Australian citizenship had limited opportunities to pursue tertiary education. Learners from low-income homes whose families had insecure or intermittent employment and who were also not eligible for Government educational assistance such as HECS-HELP might have had to forgo their aspirations to pursue tertiary studies to focus on their family livelihood needs. Furthermore, learners who pursued tertiary study relied on their families, or their own resources, to fund their tertiary education fees upfront which was a challenge (Kearney & Glen, 2017; Paulsen, 2018c). These findings suggest that Pacific learners are marginalised and in turn might experience long-term consequences for themselves, their families and their communities (see Cuthill & Scull, 2011; Kearney & Glen, 2017; Paulsen, 2018a, 2018c).

2) Other constraints on post-compulsory educational opportunities for the learner.

Other constraints on post-compulsory educational opportunities for Pacific learners included Scull and Cuthill’s (2010) study which found that contextual factors such as structural issues, settlement issues and social issues had impacted on higher education access for this cohort. Similarly, Cuthill and Scull (2011) highlighted that the constraints had interrelated factors which included school engagement and achievement, migration status, financial pressures and cultural differences. Other examples of constraints included contrasting expectations of parents and teachers (Kearney et. al., 2014); acquiring employment immediately after leaving school (Kearney & Glen, 2017; Paulsen, 2018a); upholding responsibilities to family and community which outweighed fulfilling personal aspirations (Stanley, 2019); inappropriate choice of pathways, inadequate in-home and at-school support, personal distractions, negative peer association, anti-social behaviour and non-supportive family and teachers (Ravulo, 2018).

3) Lack of professional learning and development for intercultural understanding (ICU) and intercultural capabilities (ICC).

The results also revealed that there is a lack of professional learning and development for ICU and ICC. For example, Kearney & Glen (2010) found that limited aspirations on the part of students and a lack of high expectations on the part of teachers result from a lack of ICU on the part of both students and teachers. Similarly, Paulsen (2018b) identified cultural distance as a barrier for Pacific learners, especially where the social and cultural requirements of schooling were antithetical to Pacific lived experiences and cultural forms of learning. Tualaulelei (2021) found that teachers had experienced a culture shock in highly multicultural classrooms and suggested that it might be due to the lack of opportunities for professional learning about teaching culturally and linguistically diverse students. Similarly, other studies highlighted that education has the transformative potential to be a social equaliser for culturally and linguistically diverse students (see Tualaulelei, 2017), and that there is a need for researchers and practitioners to adopt an interpretative stance that accommodates a collectivist perspective to recognise that some student behaviours may be misinterpreted and their circumstances may be unfairly undervalued (see Kearney et al., 2018). In New Zealand, for example, the Tapasā Cultural Competency Framework was developed as a tool that can be used to build the capabilities of educators and teachers of Pacific learners (Ministry of Education, 2018). This aligns with Blackberry & Kearney’s (2020) suggestion that the implications for an edu-cultural pedagogy in Australia should be considered in teacher education courses and for in-service professional learning for teachers because Pacific learners benefit from strong relational connections with their educators and teachers.

Discussion

This study is a first to map out the Australia-based research on the education of Pacific learners thus offering significant contributions. Firstly, the study serves as a guide for Pacific education research in Australian educational settings. Secondly, in mapping Pacific education research in Australia, we have extended Pacific education research and practice (particularly in relation to the Pacific diaspora) beyond New Zealand where much of the international research was developed over the past few decades.

The results from this study yielded 20 extant literature that were relevant to this scoping review. As such, a wide range of individual and societal factors appear to have influenced and impacted the successes and/or challenges of Pacific learners in Australia. For example, the contributing factors that have led to educational success for this cohort included having family support; positive expectations; developing positive relational connections between learners and teachers; and establishing effective collaborative partnerships between the education sector and Pacific communities in Australia. In contrast, the challenges to educational success for Pacific learners included a lack of access to permanent residency and/or Australian citizenship; other constraints on opportunities for the learner; and a lack of professional learning and development of ICU, ICC and ICE. The findings from this study are aligned with international research that has sought to develop and implement strengths-based approaches in education research with Pacific learners (e.g. Anae, 2016; Airini et al., 2010; Helu-Thaman, 2007; Pale, 2019; Si’ilata et al., 2019; Te Ava & Rubie-Davies, 2011; Wolfgramm-Foliaki & Smith, 2020). However, the lack of access to permanent residency and/or Australian citizenship for Pacific learners living in Australia could be a potential area of research to explore further.

Furthermore, the findings revealed that there were paucities in education research with Pacific learners particularly in the early childhood sector and in the primary sector in Australia. Kearney et al., (2014) suggested that an early intervention is necessary to help establish connections between the home and school as it may be too late to address challenges to achieving educational success for this cohort in the post-compulsory years of education. Therefore, future research within early childhood and primary sectors might help to address and support the aims of the EYLF for Australia and the Australian Curriculum through developing an understanding and respect for cultural diversity, to strengthen centre/home and school partnerships, and to develop a strong sense of identity and belonging (ACARA, 2014; ACEQA, 2021; Ohi et al., 2019; Pettitt & Tierney, 2016).

Another paucity in education research that was revealed centres on the professional development of educators, teacher, education leaders for ICU, ICE and ICC in Australia. This finding is pertinent as ICE is considered a priority for schools and schooling systems both nationally and internationally. Hence, another area for future research could focus on building capacities in ICU, ICE and ICC for educators, teachers and education leaders in relation to the education of Pacific learners. In addition, the development of pedagogical practices that are culturally and linguistically responsive for Pacific learners in Australia could be another area worthy to investigate (e.g. Airini et al., 2009; Helu-Thaman, 2001; Ponton, 2017; Tualaulelei & McFall-McCaffery, 2019; Vaioleti, 2006).

The findings also highlighted a paucity in education research that is based on how and why research involving Pacific peoples, families and communities is conducted in Australia. As noted earlier, existing international literature has emphasised the importance of education sectors working towards reducing disparities for Pacific learners in predominantly Western educational settings. However, most of the extant literature from this scoping review had implemented a Western qualitative research approach, with the exception of a few studies that had considered and/or used Pacific qualitative research approaches (e.g. Fa’avale, 2020; Stanley, 2019; Tualaulelei, 2017). Anae (2019) suggested that when Pacific research adheres to traditional Western theories and research methods this could undermine and overshadow the vā—the sacred, spiritual, and social spaces of human relationships between researcher and researched that Pacific peoples place at the centre of all interactions. The notion of vā has been applied in international research with Pacific learners (see Airini et. al., 2010; Anae et al., 2001; Fa’avae, 2019; Pale, 2019; Samu, 2011; Te Ava & Page, 2018; Reynolds, 2018; Tualaulelei & McFall-McCaffery, 2019; Vaioleti, 2006). Hence, the use or development of alternative theoretical lenses and research methods could be explored in future research by drawing on Indigenous Pacific epistemologies, and more importantly through the practice of consultation with the Pacific families and communities in Australia.

Conclusion

This scoping review offers an important synthesis of empirical research on the educational successes and challenges of Pacific learners in Australian educational settings. It contributes a strong evidence base to the critical discourse on how education sectors can work towards understanding and supporting Pacific learners. Furthermore, the paucities in education research that were revealed in this study offer propositions for future and ongoing education research with Pacific learners in Australia.

As addressed earlier, education research with Pacific learners matters in Australia as it is critical to understand what is required to achieve and sustain better educational outcomes for this cohort. This scoping review contributes to the emergence of an international or at least transnational, literature base. This study has brought into view via a robust, rigorous, authentic scholarly process, of what is known in Australia. Hence, future research in this field can expand and build upon the existing evidence base.

Data availability

All data are cited in the article which can be sought and accessed by the readers.

References

Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority [ACEQA]. (2021). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia (EYLF). Retrieved from https://www.acecqa.gov.au/nqf/national-law-regulations/approved-learning-frameworks

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA]. (2014). Intercultural understanding. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/intercultural-understanding/

Airini, B. D., Curtis, E., Johnson, O., Luatua, F., O’Shea, M., Ulugia-Pua., M. (2009). Success for all: Improving Māori and Pasifika student success in degree-level studies. Milestone report 8. Final Report. December 2009. Uniservices.

Airini, Anae, M., Mila-Schaaf, K. Coxon, E., Mara, D., & Sanga, K. (2010). Teu Le Va — Relationships across research and policy in Pasifika education: A collective approach to knowledge generation and policy development for action towards Pasifika education success. UniServices.

Amituanai-Toloa, M., & McNaughton, S. (2008). A profile of reading comprehension in English for Samoan bilingual students in Samoan bilingual classes. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 33(1), 5–20.

Amituanai-Toloa, M. (2009). What is a Pasifika research methodology? The ‘tupua’ in the winds of change. Pacific-Asian Education, 21(2), 45–53.

Amituanai-Toloa, M., McNaughton, S., & Lai, M. (2009). Biliteracy and language development in Samoan bilingual classrooms: The effects of increasing English reading comprehension. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 12(5), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050802366465

Anae, M., Coxon, E., Mara, D., Samu, T. W., & Finau, C. (2001). Pasifika education research guidelines: Final report. UniServices.

Anae, M. (2016). Teu le va: Samoan relational ethics. Knowledge Cultures, 4(3), 117–130.

Anae, M. (2019). Pacific research methodologies and relational ethics. https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-529

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Au, K. H. (2002). Communities of practice: Engagement, imagination, and alignment in research on teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(3), 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102053003005

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Australian demographic statistics, Jun 2016. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/7d12b0f6763c78caca257061001cc588/2d2860dfa430d432ca2580eb001335bb!OpenDocument

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017a). Census of population and housing: Reflecting Australia - Stories from the census, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features-Cultural%20Diversity%20Data%20Summary-30

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017b). Census of population and housing: Reflecting Australia - Stories from the census, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2071.0main+features22016

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). ANCP ancestry multi response by STATE (UR). Census TableBuilder. Retrieved from November 30, 2021.

Batley, J. (2017). What does the 2016 census reveal about Pacific Islands communities in Australia? The state, society & governance in Melanesia program (SSGM) in the ANU College of Asia & the Pacific. Australian National University.

Blackberry, G., & Kearney, J. (2020). Lessons for teachers: Maori and Pacific Islander students’ reflections on educational experiences. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 49(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2020.1793905

Cloonan, A., Fox, B., Ohi, S., & Halse, C. (2017). An analysis of the use of autobiographical narrative for me teachers’ intercultural learning. Teaching Education, 28(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1212005

Comber, B. (2015). School literate repertoires: That was then, this is now. In J. Rowsell & J. Sefton-Green (Eds.), Revisiting learning lives—Longitudinal perspectives on researching learning and literacy (pp. 16–31). Routledge.

Comber, B., & Woods, A. (2018). Pedagogies of belonging in literacy classrooms and beyond: What’s holding us back? In C. Halse (Ed.), Interrogating belonging for young people in schools (pp. 263–283). Palgrave Macmillan.

Coxon, E., Anae, M., Mara, D., Samu, T. W., & Finau, C. (2002). Literature review on Pacific education issues. University of Auckland.

Crossley, M., Vaka’uta, C. F. K., Lagi, R., McGrath, S., Helu-Thaman, K., & Waqailiti, L. (2017). Quality education and the role of the teacher in Fiji: Mobilising global and local values. Compare A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(6), 872–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2017.1338938

Cuthill, M., & Scull, S. (2011). Going to university: Pacific Island migrant perspectives. Australian Universities Review, 53(1), 5–13.

Daza, V., Gudmundsdottir, G., & Andreas Lund, A. (2021). Partnerships as third spaces for professional practice in initial teacher education: A scoping review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 102, 103338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103338

Dorling, D. (2016). A better politics: How government can make us happier. London Publishing Partnership.

Dun, O., & Klocker, N. (2017). The Migration of Horticultural Knowledge: Pacific Island seasonal workers in rural Australia—a missed opportunity? Australian Geographer, 48(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2017.1272528

Enari, D., & Haua, I. (2021). A Maori and Pasifika label: an old history, new context. Genealogy, 5(70), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030070

Faas, D. (2008). From foreigner pedagogy to intercultural education: An analysis of the German responses to diversity and its impact on schools and students. European Education Research Journal, 7(1), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2008.7.1.108

Fa’avae, D. (2018). Giving voice to the unheard in higher education: Critical autoethnography, Tongan males, and educational research. MAI Journal, 8(2), 126–138.

Fa’avae, D. (2019). Tatala ‘a e koloa ‘oe to’utangata Tonga: A way to disrupt and decolonise doctoral research. MAI Journal: New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship, 8(1), 3–15.

Fa’avale, A., O’Brien, G., Green, A., & McLaughlin, J. (2016). May the coconut tree bear much fruit – QUT’s ‘niu’ framework for outreach and retention with Pasifika students In Field, R & Nelson, K. (Eds.). Proceedings of the 2016 Students, Transitions, Achievement and Retention and Success (STARS) Conference. Office for Learning and Teaching, Australia (pp. 1–6).

Fa’avale, A. (2020). Pasifika student self-efficacy: Minding the mindset of success. [Unpublished master's thesis]. Griffith University.

Faleolo, R. (2019). Wellbeing perspectives, conceptualisations of work and labour migration experiences of Pasifika trans-Tasman migrants in Brisbane. In V. Stead & J. Altman (Eds.), The labour lines and colonial power (pp. 185–206). ANU Press.

Fray, L., & Gore, J. (2018). Why people choose teaching: A scoping review of empirical studies, 2007–2016. Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.009

Froiland, J. M., Davison, M. L., & Worrell, F. C. (2016). Aloha teachers: Teacher autonomy support promotes Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander students’ motivation, school belonging, course-taking and math achievement. Social Psychology of Education, 19(4), 879–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9355-9

Gore, J., Patfield, S., Fray, L., Holmes, K., Gruppetta, M., Lloyd, A., Smith, M., & Heath, T. (2017). The participation of Australian Indigenous students in higher education: A scoping review of empirical research, 2000–2016. Australian Educational Researcher, 44, 323–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0236-9

Grainger, A. (2006). From immigrant to overstayer Samoan identity, rugby, and cultural politics of race and nation in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 3(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723505284277

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26, 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Halse, C. (2018). Theories and theorising of belonging. In C. Halse (Ed.), Interrogating belonging for young people in schools (pp. 1–28). Palgrave Macmillan.

Helu-Thaman, K. (1992). Looking towards the source: A consideration of (cultural) context in teacher education. In C. Benson & N. Taylor (Eds.), Pacific teacher education forward planning meeting: Proceedings (pp. 3–13). Institute of Education.

Helu-Thaman, K. (1997). Reclaiming a place: Towards a Pacific concept of education for cultural development. The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 106(2), 119–130.

Helu-Thaman, K. (2001). Towards culturally inclusive teacher education with specific reference to Oceania. International Education Journal, 2(5), 1–8.

Helu-Thaman, K. (2007, September 28-October 1). Kakala: A Pacific concept of teaching and learning [Conference Paper]. The Australian College of Educators National Conference, Cairns, Queensland.

Kearney, J., & Donaghy, M. (2010, June 27–30). Bridges and barriers to success for Pacific Islanders completing their first year at an Australian university [Conference Paper]. The 13th Pacific Rim First Year in Higher Education Conference, Adelaide. https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au/handle/10072/38990

Kearney, J., Fletcher, M., & Dobrenov-Major, M. (2014). Non-aligned worlds of home and school: A case study of second- generation Samoan children. Journal of Family Studies, 17(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2011.17.2.146

Kearney, J., & Glen, M. (2017). The effects of citizenship and ethnicity on the education pathways of Pacific youth in Australia. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 12(3), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197916684644

Kearney, J., Stanley, G., & Blackberry, G. (2018). Interpreting the first-year experience of a non-traditional student: A case study. Student Success, 9(3), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v9i3.463

Keehne, C. K., Sarsona, M. W., Kawakami, A. J., & Au, K. H. (2018). Culturally responsive instruction and literacy learning. Journal of Literacy Research, 50(2), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X18767226

Kepa, M., & Manu’atu, L. (2006). ‘Fetuiakimalie, talking together’: Pasifika in mainstream education. Waikato Journal of Education, 12, 51–56.

Kepa, M., & Manu’atu, L. (2008). Pedagogical decolonization: Impacts of European/Pakeha society on the education of Tongan people in Aotearoa, New Zealand. The American Behavioral Scientist, 51(12), 1801–1816. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764208318932

Leeman, Y. (2008). Education and diversity in the Netherlands. European Educational Research Journal, 7(1), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2008.7.1.50

MacDonald, L., & Lipine, T. (2012). Pasifika education policy, research and voices: Students on the road to tertiary success. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 21, 143–164.

Maebuta, J. (2011). The education Pacific Islands children deserve: The learn and play project in the Solomon Islands. Australian and New Zealand Comparative and International Education Society, 10(2), 99–112.

Manu’atu, L. (2000). Katoanga Faiva: a pedagogical site for Tongan students. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 32(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2000.tb00434.x

Ministry of Education. (2013). Pasifika education plan 2013–2017. Ministry of Education, New Zealand.

Ministry of Education. (2018). Tapasā: Cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pacific learners. Ministry of Education, New Zealand.

Niemi, P., Kuusisto, A., & Kallioniemi, A. (2014). Discussing school celebrations from an intercultural perspective – a study in the Finnish context. Intercultural Education, 25(4), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2014.926143

Ofamo’oni, J., & Rowe, N. (2020). The Mafana framework: How Pacific students are using collaborative tasks to decolonize their learning. Higher Education Research and Development, 41(2), 496–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1852392

Otunuku, M., Brown, G., & Airini, L. (2013). Tongan secondary students’ conceptions of schooling in New Zealand relative to their academic achievement. Asia Pacific Education Review, 14(3), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-013-9264-y

Ohi, S., O’Mara, J., Arber, R., Hartung, C., Shaw, G., & Halse, C. (2019). Interrogating the promise of a whole-school approach to intercultural education: An Australian investigation. European Educational Research Journal, 18(2), 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904118796908

Pale, M. (2019). The Ako Conceptual Framework: Toward a culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 47(5), 539–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2019.1575945

Paulsen, I. (2016). Negotiating pathways: rethinking collaborative partnerships to improve the educational outcomes of Pacific Islander young people in Melbourne’s Western region. Unpublished PhD thesis, College of Education, Victoria University.

Paulsen, I. (2018a). Predictable pathways: Pacific Islander learners and school transitions in Melbourne’s western region. The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 17(2), 77–87.

Paulsen, I. (2018b). Relationships, relationality and schooling: Opportunities and challenges for Pacific Islander learners in Melbourne’s western suburbs. The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 17(3), 39–54.

Paulsen, I. (2018c). Migration background and educational affordability amongst Pacific Islander migrant learners in Melbourne’s western region. Journal of Social Inclusion, 9(2), 51–72.

Ponton, V. (2017). An investigation of Samoan student experiences in two homework study groups in Melbourne. Sociology Study, 7(7), 349–363.

Ponton, V. (2018). Utilizing Pacific methodologies as inclusive practice. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018792962

Pettitt, A., & Tierney, S. (2016). Building belonging: A toolkit for early childhood educators on cultural diversity and responding to prejudice. Australian Human Rights Commission.

Raturi, S., Hogan, R., & Helu-Thaman, K. (2011). Learners’ access to tools and experience with technology at the University of the South Pacific: Readiness for e-learning. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(3), 411–427.

Ravulo, J. (2015). Pacific communities in Australia. Western Sydney University.

Ravulo, J. (2018). Risk and protective factors for Pacific communities around accessing and aspiring towards further education and training in Australia. Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 20(1), 8–38. https://doi.org/10.5456/WPLL.20.1.8

Ravulo, J. (2019). Raising retention rates towards achieving vocational and career aspirations in Pacific communities. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 38(2), 214–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2019.1585393

Reynolds, M. (2018). Caring for classroom relationality in Pasifika education: A space-based understanding. Waikato Journal of Education, 23(1), 71–84.

Rogers, R. (2011). The sounds of silence in educational tracking: A longitudinal, ethnographic case study. Critical Discourse Studies, 8(4), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2011.601632

Samu, T. W. (2010). Pacific education: An Oceanic perspective. MAI Review, 1, 1–14.

Samu, T. W. (2011). Understanding the lines in the sand: Diversity, its discourses and building a responsive education system. Curriculum Matters, 7, 175–194.

Samu, T. W. (2020). Charting the origins, current status and new directions within Pacific/Pasifika education in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 26, 197–207.

Scull, S., & Cuthill, M. (2010). Engaged outreach: Using community engagement to facilitate access to higher education for people from low socio-economic backgrounds. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903421368

Si’ilata, R., Samu, T.W., & Siteine, A. (2019). The Va’atele framework: redefining and transforming Pasifika education. In E. A. McKinley & L. T. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of indigenous education (pp. 907–936). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3899-0_34

Smith, H., & Wolfgramm-Foliaki, E. (2021). ‘We don’t talk enough’: Voices from a Māori and Pasifika lead research fellowship in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1856791

Stanley, G. (2019). Aspirations of Pacific Island high school students for university study in Southeast Queensland. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Griffith University.

Stanley, G., & Kearney, J. (2017). The experiences of second generation Samoans in Australia. Journal of Social Inclusion, 8(2), 54–65.

Tharp, R. G. (1982). The effective instruction of comprehension: Results and description of the Kamehameha Earl Education Program. Reading Research Quarterly, 17(4), 503–527.

Te Ava, A., & Page, A. (2018). How the Tivaevae model can be used as an indigenous methodology in Cook Islands education settings. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2018.9

Te Ava, A., & Rubie-Davies, C. (2011). Akarakara akaouanga i te kite pakari o te kuki airani: Culturally responsive pedagogy. Pacific-Asian Education Journal, 23(2), 117–127.

Tualaulelei, E., & Kavanagh, M. (2015). University-community engagement: Mentoring in the Pasifika space. Australasian Journal of University-Community Engagement, 10(1), 87–106.

Tualaulelei, E. (2017). Exploring the academic (under)achievement of Samoan students in a Queensland primary school: Perspectives and potentialities. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of Southern Queensland, Australia.

Tualaulelei, E. (2021). Professional development of intercultural education: Learning on the run. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 49(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2020.1753168

Tualaulelei, E., & McFall-McCaffery, J. (2019). The Pacific research paradigm: Opportunities and challenges. MAI Journal, 8(2), 188–204.

Turner, K., & Stough, C. (2019). Pre-service teachers and emotional intelligence: A scoping review. The Australian Educational Researcher, 47, 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00352-0

Vaioleti, T. M. (2006). Talanoa research methodology: A developing position on Pacific research. Waikato Journal of Education, 12, 21–34.

Wolfgramm-Foliaki, E., & Smith, H. (2020). Navigating Maori and Pasifika student success through a collaborative research fellowship. MAI Journal, 9(1), 5–14.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Adjunct Associate Professor Judith Kearney at Griffith University, and Dr. Sarah Ohi at Deakin University, for accepting the invitation to participate in the consultation process for this scoping review as two experts in the education field. Their time, invaluable feedback and academic guidance are much appreciated.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the Open Access funding that was enabled and organised by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The lead author would also like to acknowledge the Swinburne Women Academic Network at Swinburne University of Technology for the grant received in support of the completion of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The lead author decided to conduct a scoping review for the article and acquired funding from Swinburne University of Technology to help complete the work. The second author worked with the lead author to determine search terminologies, then populated the relevant statistics from the Australian census data, performed the literature search and produced the preliminary results. In following, the lead author consulted with two experts in the education field regarding the preliminary results. Next, the lead author completed the first draft of the article and worked closely with all co-authors to critically revise the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest and there are no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pale, M., Kee, L., Wu, B. et al. Takanga ‘enau fohe: a scoping review of the educational successes and challenges of Pacific learners in Australia 2010–2021. Aust. Educ. Res. 51, 515–546 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00611-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00611-1