Abstract

This article reports on original research investigating teacher wellbeing while teaching mathematics in relation to teacher identity. Using survey data from mathematics teachers (N = 402) participating in a teacher of mathematics support initiative, teacher wellbeing was operationally defined as the experience of wellbeing whilst teaching, allowing an applied understanding of wellbeing in relation to the activity of teaching. Teacher identity was construed from prior research by the authors (Willis et al., in: Math Educ Res J, 10.1007/s13394-021-00391-w, 2021) and operationalised for the current study in terms of a specific teacher of mathematics identity (ToMI) construct. The main research question for this investigation was directed at how well the ToMI construct, as a wellbeing variable, was able to predict teacher wellbeing while teaching, viewed as an ‘in situ’ or ‘active’ (applied) measure of wellbeing. Identity-Based Motivation (IBM) theory was used to frame the research, as it helps explain how the degree of congruency between identity and wellbeing may influence motivation to teach. Results indicated that although several important factors relate significantly to teacher of mathematics wellbeing, the ToMI construct predicted teacher wellbeing far above the ability of all other study factors combined, suggesting that a focus on the development of a professional identity for teachers is fundamental to the support of teacher wellbeing in schools. Suggestions for investigating this focus at the school level are also provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Wellbeing has been a topic of research for decades (Diener, 2000; Gruber et al., 2011; Markus & Nurius, 1986; Powell et al., 2018; Quoidbach et al., 2014), largely due to the impact wellbeing can have on social and professional capacity (Smylie et al., 2016; Tamir, et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). Wellbeing research encompasses multiple types and models of wellbeing. The definition of wellbeing varies in relation to the context surrounding its applied field (health, education, psychology; Camfield et al., 2009; Dodge et al., 2012).

This article reports on an investigation into the ability of identity to predict wellbeing for mathematics teachers. By doing so, the article extends prior work by the authors aimed at developing a Teacher of Mathematics Identity (ToMI) measure (Willis et al., 2021), using data from the Regional Teacher of Mathematics Network (RTMN) project. This project aims to discover ways to support wellbeing for teachers of mathematics.

Willis et al. (2021) developed a quantitative scale of ToMI based on three central tenets: Belonging to a mathematics community, self-efficacy as a teacher of mathematics, and enthusiasm to be a teacher of mathematics. Using exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis, they discovered and confirmed the three-factor solution supporting these tenets, but also found that a single underlying factor of ToMI explained a significant proportion of the variance in the teacher of mathematics responses. The ToMI scale was found to have good internal reliability, and validity was determined by assessing correlations with variables theorised to relate to ToMI, such as years teaching mathematics (experience/expertise), self-directed professional learning (professional agency) and mathematics teacher network (professional belonging). The current study investigated how well ToMI predicts teacher wellbeing while teaching mathematics after accounting for other individual, social, and contextual factors.

Defining wellbeing

The notion of wellbeing has been broadly conceptualised as occurring along a continuum that ranges from hedonic to eudemonic (Diener et al., 1985; Vittersø, 2016) and includes physical (Powell et al., 2018; Tunajek, 2019), social-emotional (Schonert-Reichl, 2017) and mental wellbeing factors (Coffey et al., 2013; Powell & Graham, 2017). Trans-cultural research has also suggested the inclusion of psychological richness as an element of wellbeing (Oishi et al., 2019), incorporating attributes such as receptiveness to new ideas and social connection as important to wellbeing.

The nature of wellbeing appears context-driven, as seen in how wellbeing has been differentially modelled in relation to its applied field. For example, Gilliver (2021) suggests a Five Ways model of wellbeing for the nursing profession. This model has been adopted by the National Health System (NHS) in England and focusses on five activities viewed as beneficial to feeling and functioning well professionally: Connecting with others, living an active lifestyle, cultivating curiosity, actively engaging in lifelong learning and providing service to the broader community.

Psychological wellbeing has generally been conceived in more introspective terms, such as Ryff’s six-criteria for wellbeing (Ryff & Singer, 2006), which emphasises ‘virtuous living’ via self-acceptance, personal growth, creating self-purpose, establishing positive relationships with others, understanding one’s ability to master their environment and positioning one’s ability to self-determine.

The Alliance for Healthier Communities has developed a model for the delivery of primary health care (https://www.allianceon.org/model-health-and-wellbeing). In alignment with the World Health Organization, this model defines health and wellbeing in fairly generalised terms as representing a “state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.

Common denominators across wellbeing constructs are that they link wellbeing to performance, integrate physical, cognitive and social-emotional functioning, and emphasise the ability to navigate psychosocial and environmental complications. They also highlight the subjectivity of wellbeing and suggest that context influences how wellbeing is defined and experienced for individuals (Fraillon, 2014; La Placa et al., 2013).

With respect to education, Noble et al. (2008) define wellbeing in terms of positive emotions and attitudes that produce satisfaction with one’s sense of self and provide an increase in workplace commitment. This aligns with Seligman’s (2011) PERMA (Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning and Accomplishment) framework, another generalised model for wellbeing that has also been endorsed as a viable framework for teacher wellbeing (Cann, 2019; Gregersen et al., 2020; Hollweck, 2019; Kern et al., 2015). We refer to this framework because of its focus on the positive emotions that come from social contact and the development of personal meaning, which suggests the need for a positive professional identity. The aims of the PERMA framework also coincide with those of the current investigation, to create a supportive and productive working environment, wherein teachers can identify with their professional roles in ways that produce increased satisfaction and professional commitment.

The research being reported here adds to the educational understanding of wellbeing by its investigation of the ability of teacher identity to predict the experience of wellbeing for mathematics teachers whilst teaching. This addresses a gap in our understanding of teacher wellbeing, wherein specific research into a possible relationship between teacher identity and the experience of wellbeing whilst teaching remains absent from the current research literature, although Kiltz et al. (2020) and McCallum and Price (2015) have implied the importance of such a relationship. The focus of the current investigation seeks to fill this gap. It also represents an understanding of wellbeing that may help to mediate the teacher’s impact on student outcomes (Benevene et al., 2019; Glazzard & Rose, 2019) and which involves quite distinct elements and characteristics of wellbeing in relation to teaching that require specific examination (O’Connor & Thomas, 2019; Willis & Grainger, 2020).

Investigating the relationship between teacher identity and teacher wellbeing also provides an opportunity to operationalise wellbeing in a way that is relevant to classroom teaching, allowing the current research to investigate teacher wellbeing within a framework that has applied value to the field of education. In this respect, teacher wellbeing is defined for the current research as the experience of wellbeing whilst teaching. This form of wellbeing can be seen as an outcome of various support factors that influence the experience of wellbeing whilst working within a specific context.

Theoretical framework

Identity-Based Motivation (IBM) theory, a social psychological theory concerning the relationship between human motivation and goal pursuit (Oyserman & Destin, 2010), was used to frame the current investigation. IBM theory seeks to explain how context influences the degree to which a person’s identity motivates them to work towards their goals by focussing on ways in which identity-congruent versus identity-incongruent actions affect engagement motivation. The gist of this theory is that when actions feel identity-congruent, the difficulty of performing an action conveys a message that the action is important and meaningful. When an action feels identity-incongruent, however, the same level of difficulty suggests that it is pointless and not for people like me.

IBM relates to the focus on teacher wellbeing for the current study because it suggests that when the teaching behaviours of mathematics teachers are more congruent with their ToMI, they will perceive these behaviours as important and experience positive wellbeing in relation to their mathematics teaching. Conversely, when the teaching behaviours of these teachers are less congruent with their ToMI, they will perceive these behaviours as unimportant and experience negative wellbeing in relation to their mathematics teaching. We discuss the implications relating to IBM/ToMI congruency further in the discussion section of this report.

Prior teacher wellbeing research

Prior research in the area of teacher wellbeing has indicated that mathematics teaching is influenced by teacher identity (Ingram et al., 2018), that pedagogical competence is closely linked to teacher wellbeing (Fernandes et al., 2019), that access to high-quality professional learning (PL) has an impact on teacher retention (Broadley, 2010) and serves to increase teacher wellbeing (Mansfield & Gu, 2019), and that an increased sense of social support and belonging provide support for teacher wellbeing (Granziera et al., 2020; McCallum & Price, 2015; Renshaw, 2002; Rowe & Stewart, 2009).

The gist of prior teacher wellbeing research is that a close relationship exists between teacher identity and teacher wellbeing, that teacher wellbeing is connected to a sense of social contact, and that the confidence and competence provided by appropriate PL contribute to teacher wellbeing. These relationships suggest that teacher wellbeing needs to be investigated in relation to professional identity, as this identity interacts with the available social support mechanisms and individual teacher differences that can empower and disempower teacher wellbeing within a particular context. It also suggests that the important goals of teacher wellbeing research need to include a PL approach for teachers that emphasises the relationship between identity and wellbeing.

The investigation

As noted, the current investigation focussed on the relationship between identity and wellbeing for teachers of mathematics involved in an ongoing teacher of mathematics support initiative, the RTMN Project. This project is currently being undertaken by the Mathematical Association of NSW (MANSW) in conjunction with a university partner the authors are associated. The larger purpose of this project is to provide innovative, effective and sustainable solutions to support the challenges that teachers of mathematics face (Lynch et al., 2020). The approach to this provision is to afford an overarching ToMI framework (Lynch et al., 2020) as an adaptive solution designed to lay supportive foundations for mathematics teachers that are capable of attracting, retaining, and professionally developing quality teachers in this area (Bui et al., 2020). To date, outcomes of this project have included the creation of a transformational ToMI framework that is driven by professional affiliation (Lynch et al., 2020), an associated Communities of Practice (CoP) wherein this identity can be developed and progressed (Bui et al., 2020), and the institution of socially supportive PL strategies by which the competence and confidence of mathematics teachers can be mentored and encouraged (Woolcott et al., 2021).

The current report extends these outcomes by its investigation of the impact of teacher identity (ToMI) on teacher wellbeing across the range of individual teacher differences, school contexts and social contact that occur within the RTMN project. The purpose of this positioning was to investigate how teacher of mathematics wellbeing might be influenced by the distinctive elements and characteristics of professional identity in ways that are able to provide insights concerning how to support mathematics teachers in relation to the issues they face as teachers of mathematics working within the participating RTMN schools.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the factors of interest for the investigation. We provide this overview because it acknowledges that multiple factors can influence teacher wellbeing and because it positions wellbeing within the specific study context of the RTMN project.

Working from the factors proposed in Fig. 1, the main research question addressed by the current investigation was: How well does ToMI predict teacher wellbeing while teaching mathematics, after accounting for individual, social, and contextual factors?

Related sub-questions were also addressed, including:

-

1.

To what degree do teacher individual factors influence teacher wellbeing while teaching mathematics?

-

2.

To what degree does context influence teacher wellbeing while teaching mathematics after accounting for individual factors?

-

3.

To what degree does social support influence teacher wellbeing while teaching mathematics after accounting for individual and contextual factors?

In relation to these research questions, please note the following:

-

The main research question involving ToMI was designed to focus our investigation on the predictive value of teacher identity in relation to teacher wellbeing.

-

The sub-question about context refers to overall years teaching, years teaching mathematics, grades taught, years teaching at current school, and whether the school was urban/regional/rural/remote.

-

Social contact involves activities around networking and collaboration, measured in terms of contact with others for the purpose of mathematics teaching support. An assumption for this variable is that higher-versus-lower contact frequency over time provides some indication of the amount of social support that is taking place, with the amount of social support also influencing sense of belonging.

-

Teacher individual factors refer to age and gender for the study.

Methods

Participants

Participants consisted of members of a state-level professional association for teachers of mathematics in Australia who currently teach mathematics (N = 402; Female = 265; Male = 137). Teachers had a mean age of 47.65 (SD = 11.59). Participants varied in location type (rural/remote = 14.2%; regional = 29.0%; major city = 56.7%) and grades taught (primary school = 10.7%; secondary school = 89.3%). The mean number of years teaching mathematics was 16.88 (SD = 12.11) and the mean number of years teaching at their current school was 8.49 (SD = 8.03). The research was approved by the Southern Cross University human ethics committee, with participation being voluntary, withdrawal permitted without penalty, and anonymity fully maintained.

Materials

Teacher of Mathematics Identity (ToMI)

As noted, Teacher of Mathematics Identity (ToMI) was measured via a scale developed using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis by Willis et al. (2021). For the current study, the 15-item single-factor solution was used, which revealed good internal reliability (α = 0.86). This score tapped into teacher perceptions of their belonging to a mathematics community, their self-efficacy as a teacher of mathematics and their enthusiasm to be a teacher of mathematics. Responses were made on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

Belonging to school

Belonging to School, which is not to be confused with the Belonging to a Mathematics Community subscale in the ToMI scale, measures how much a teacher feels they belong within the current school in which they teach. Belonging to School was measured using four items developed for this research: I have good relations with the other teachers at my school; I fit in with the other teachers at my school; I feel alone at the school where I teach (reverse scored); and I feel unsupported by the other teachers at my school (reverse scored). This scale was found to have satisfactory internal reliability (α = 0.71). Responses were made on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). The small correlation between the ToMI mean score and Belonging to School (see Table 2), as well as a small correlation between the ToMI Belonging to a mathematics community subscale mean score and Belonging to School (Kendall’s tau-b, τb(402) = 0.19) reveals a clear distinction between these constructs.

Network member communication frequency

Assessment of the frequency of communications made with certain network members (other teachers of mathematics, other teachers who did not teach mathematics, professional associations, and school leadership) was made using the question: How frequently do you typically communicate with the following “people/organisations” regarding your teaching of mathematics? Responses available were rarely/never (1), once every few months (2), monthly (3), fortnightly (4), weekly (5), several times per week (6) and daily (7).

Wellbeing while teaching mathematics

Wellbeing while teaching mathematics was measured using six items adapted from Topp et al. (2015). One item was removed due to irrelevance (I woke up feeling fresh and rested) and two reverse coded items were added. Respondents were asked to respond to the statements: In general, while teaching mathematics: … I feel cheerful and in good spirits; … I feel calm and relaxed; … I feel active and vigorous; … I find my classes interesting; …I feel frustrated (reverse scored); and …I get annoyed (reverse scored). Responses available were never (1), sometimes (2), about half the time (3), most of the time (4) and always (5). Good internal reliability was found for these items (α = 0.824).

Design and analysis

A cross-sectional design was used in this study. Mean scores were calculated for individual participants for each of the scales used and reported as descriptive statistics. These were then used in the initial correlational analysis and in subsequent hierarchical multiple regression to assess how well the included variables predicted wellbeing while teaching mathematics. This analysis was chosen for its functionality to build models while controlling for previous models included. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 26.

Results

Descriptive statistics for all continuous variables used are shown in Table 1, and Kendall’s tau-b correlations for the same variables can be seen in Table 2. Kendall’s tau-b is a non-parametric form of correlation that overcomes issues with normality in some of the variables, namely frequency data, which are positively skewed. Although there are a number of significant correlations, we will highlight only those with medium and large effect sizes according to Cohen’s (1988) suggestions. As might be expected, there are positive relationships between years teaching mathematics, years teaching in current school and age. ToMI was positively correlated with wellbeing while teaching mathematics. Frequency of contact with school leadership was also positively correlated with frequency of contact with teachers who do not teach mathematics.

Hierarchical multiple regression results are shown in Table 3, where model 1 includes the individual characteristics of gender and age; model 2 then adds contextual variables (school location, teaching experience, and sense of belong to school) while controlling for variables in model 1; model 3 then adds social support elements in the form of frequency of contact with other teachers and staff, and professional association, while controlling for the variables included in models 1 and 2; and finally, model 4 adds ToMI, while controlling for all the variables previously included. To clarify, controlling for the previous variables included in each model allowed the predictive value of the newly added variable(s) to be revealed after taking into account the variation in scores due to these previous variables. Thus, after we factored in the variation from all prior variables, model 4 revealed how much ToMI predicts wellbeing while teaching mathematics after controlling for this prior variance.

Table 3 shows the unstandardised and standardised regression coefficients of the models predicting wellbeing while teaching mathematics. Each model predicted a significant amount of the variance in wellbeing while teaching mathematics: model 1, F(2, 399) = 4.64, p = 0.010; model 2, F(8, 393) = 4.07, p < 0.001; model 3, F(12, 389) = 3.68, p < 0.001; model 4, F(13, 388) = 13.88, p < 0.001. Of note, the grade levels being taught negatively predicted a significant amount of the variance in wellbeing while teaching mathematics, indicating that primary teachers experienced higher levels of wellbeing than secondary teachers. This experience reaches significance in models 2 and 4 and suggests that primary teachers enjoyed higher levels of wellbeing while teaching mathematics than secondary teachers in general.

Sense of belonging to the school predicted wellbeing while teaching mathematics in models 2 and 3 but is not significant in model 4. This suggests that a sense of belonging to the school was important for wellbeing while teaching mathematics, but ToMI explains much of the same variance and more unique variance on top of this. Thus, it may be that although a sense of belonging to the school was more important in promoting higher levels of wellbeing while teaching mathematics for teachers with lower levels of ToMI; those higher in ToMI relied less on a sense of belonging to the school for their wellbeing.

Social contact with other teachers of mathematics and the school leadership also predicted higher levels of wellbeing while teaching mathematics in model 4. That is, after controlling for individual and contextual variables included in models 1 and 2, the more a teacher had contact with other teachers of mathematics and school leadership, the more wellbeing while teaching mathematics they had.

Finally, after controlling for the individual, contextual, and social contact variables included in models 1, 2, and 3, ToMI significantly predicted wellbeing while teaching mathematics. As shown in Table 3, using the standardised regression coefficients (which can be directly compared), and the jump in the R2 effect size for model 4, it is clear that ToMI had substantially more impact on wellbeing while teaching mathematics than all other variables included in the regression analysis. This effect is perhaps more clearly seen by converting R2 to a percentage, which reveals that whereas individual, contextual and social contact variables account for approximately 10% of the variance in wellbeing while teaching mathematics, by adding ToMI, the model explains approximately 30% of this variance.

Table 4 includes a regression model with only the significant predictors from model 4 of the hierarchical regression analysis. Here, we also report semi-partial squared correlations for the predictors, which indicate the unique variance explained by each predictor. This reveals that teaching grades (primary versus high school, with high school predicting lower wellbeing) and frequency of contact with other ToMs and leadership each explain about 1% of the variance in wellbeing while teaching maths. ToMI, on the other hand, explains 25% of the variance in wellbeing while teaching maths. This model thus explained a significant amount of the variance in wellbeing while teaching mathematics, F(4, 397) = 39.87, p < 0.001.

Discussion

These findings extend our understanding of teacher wellbeing by identifying the influence that professional identity can have on wellbeing of teachers while teaching mathematics, thus supporting research claiming that mathematics teaching is influenced by teacher identity (Ingram et al., 2018). They also support prior research suggesting that pedagogical competence is closely linked to teacher wellbeing (Fernandes et al., 2019), that teacher wellbeing has an impact on teacher retention (Broadley, 2010), and that a sense of social support and belonging increases teacher wellbeing (Renshaw, 2002). In addition, they offer support to the PERMA framework (Hollweck, 2019; Seligman, 2011) by implying that the positive emotions which stem from social support and a sense of belonging are important to teacher wellbeing.

In accordance with the current findings, core teacher of mathematics wellbeing issues can be identified as teachers needing supportive collegial and leadership contact, being encouraged to work collaboratively and being provided a sense of identity and belonging via connection to one another and to a relevant professional association (Cann, 2019; Gregersen et al., 2020). According to prior research by the authors (Bui et al., 2020), it is additionally suggested that initiating an appropriate CoP within and across schools is helpful in addressing such issues in schools. This is also in-line with prior research by others, which has proposed that for wellbeing to flourish, there needs to be an intentional approach to promoting strong teacher identity, which can be supported by such a community (Butler & Kern, 2016; Cann, 2019). We offer suggestions for providing this type of support in the Future Research section.

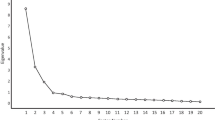

Importantly, the ToMI outcome extends the findings from prior research to include the particular relationship between teacher identity and the experience of wellbeing whilst teaching. This indicates that ToMI subsumes core aspects of teacher wellbeing such as sense of belonging, teacher self-efficacy, and enthusiasm for teaching. This finding can also be interpreted from the perspective of IBM theory, wherein ToMI can be used to represent the degree of congruency between identity and wellbeing, thereby implying that ToMI may be used as a proxy indicator for teacher motivation. This interpretation is presented in Fig. 2, which depicts motivation occurring along a continuum that is controlled by ToMI level. From this perspective the ToMI finding highlights a need for schools to create identity-forming pathways to support positive teacher wellbeing, as also discussed in the future research section.

Future research

Because of the close relationship between teacher identity and teacher wellbeing, we suggest that future research focus on investigating how to support teacher identity at a school-based level. The aim of this research would be to support identity-creation/identity-strengthening for the participating teachers.

Self-analysis of identity as a professional teacher would be the core focus for this research, involving teachers analysing and reflecting on who they are as a teacher, how they experience teaching, the degree to which they are motivated to engage in their teaching and the level at which their teaching reflects an authentic inner sense of purpose as a teacher. Motivational data, in particular, can be used to ascertain teacher congruency for IBM/ToMI as part of this research, seeking to provide further evidence of ToMI as a possible proxy for teacher motivation.

Stimulus questions could be used to assist in a self-reflective process as part of the investigation, aimed at getting teachers to reflect on (for example), how confident they feel when teaching, how much self-esteem they experience in relation to their teaching, the degree to which they experience spontaneity and creativity as part of their teaching and what role personal learning and curiosity play as an ongoing basis for their teaching. An initial stimulus question might be, “As you are teaching, does this make you feel more authentic and genuine, or less authentic and genuine?”.

To action this approach, future research could implement a PL initiative that encourages self-analysis of identity as a professional teacher. Research for this initiative would best occur within a mixed-methods data collection approach designed to collect pre-and-post data on identity and confidence changes, coupled to ongoing interview and focus group discussions concerning the wellbeing experiences of teachers. To include curriculum areas beyond mathematics, the reflective process could also be coupled to a competency check list designed to guide teachers in relation to specific curriculum area competencies, and possibly scaffolded by collaborative peer-to-peer mentoring and input from a relevant professional association. This would allow triangulation from multiple data sources for the research and suit research within a CoP or whole-school improvement initiative. We believe this type of research would add worthwhile knowledge to our understanding of how to design for the support of teacher wellbeing in a systematic and applied manner.

Data availability

The raw data, and analyses of this data by the authors, can be made available upon request. This material is voluminous, however, and therefore cannot be included within the word limits of the article itself.

Code availability

FOR: 130303—Education Assessment and Evaluation. SOE (either): 930403—School/Institution Policies and Development; 930501—Education and Training Systems Policies and Development.

Change history

28 November 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00586-5

References

Benevene, P., De Stasio, S., Fiorilli, C., Buonomo, I., Ragni, B., Briegas, J. J. M., & Barni, D. (2019). Effect of teachers’ happiness on teachers’ health. The mediating role of happiness at work. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2449. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02449

Broadley, T. (2010). Digital revolution or digital divide: Will rural teachers get a piece of the professional development pie? Education in Rural Australia, 20(2), 63–76.

Bui, V., Woolcott, G., Peddell, L., Yeigh, T., Lynch, D., Ellis, D., Markopolous, C., Willis, R., & Samojlowicz, D. (2020). An online support system for teachers of mathematics in regional, rural and remote Australia. Australian & International Journal of Rural Education, 30(3), 69–88.

Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(3), 2016. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

Camfield, L., Streuli, N., & Woodhead, M. (2009). What’s the use of ‘wellbeing’ in contexts of child poverty? Approaches to research, monitoring and children’s participation. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 17, 65–109.

Cann, R. F. (2019). Positive school leadership for flourishing teachers. The University of Auckland. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/2292/49322/whole.pdf?sequence=2

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Coffey, M., Dugdill, L., & Tattersall, A. (2013). Stress in social services: Mental wellbeing, constraints and job satisfaction. The British Journal of Social Work, 34(5), 735–746. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch088

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective wellbeing: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Dodge, R., Daly, A. P., Huyton, J., & Sanders, L. D. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v.2i3.4

Fernandes, L., Peixoto, F., Gouveia, M. J., Silva, J. C., & Wosnitza, M. (2019). Fostering teachers’ resilience and wellbeing through professional learning: Effects from a training programme. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(4), 681–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00344-0

Gilliver, C. (2021). The Five Ways to Wellbeing model: A framework for nurses and patients. Nursing times, 117(5), 48–52.

Glazzard, J., & Rose, A. (2019). The impact of teacher wellbeing and mental health on pupil progress in primary schools. Journal of Public Mental Health, 19(4), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-02-2019-0023

Granziera, H., Collie, R., & Martin, A. (2020). Understanding teacher wellbeing through job demands-resources theory, In C. F. Mansfield (Ed.). Cultivating teacher resilience (pp. 229–244). Springer. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/41720/2021_Book_CultivatingTeacherResilience.pdf?sequence=1#page=233

Gregersen, T., Mercer, S., MacIntyre, P., Talbot, K., & Banga, C. A. (2020). Understanding language teacher wellbeing: An ESM study of daily stressors and uplifts. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820965897

Gruber, J., Mauss, I. B., & Tamir, M. (2011). A dark side of happiness? How, when, and why happiness is not always good. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(3), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611406927

Hollweck, T. (2019). “I love this stuff!”: A Canadian case study of mentor–coach wellbeing. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 8(4), 325–344. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-02-2019-0036

Ingram, N., Offen, B., & Linsell, C. (2018). Growing mathematics teachers: Pre-service primary teachers’ relationships with mathematics. Mathematics Teacher Education and Development, 20(3), 41–60.

Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2015). A multidimensional approach to measuring wellbeing in students: Application of the PERMA framework. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.936962

Kiltz, L., Rinas, R., Daumiller, M., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & Jansen, E. P. W. A. (2020). ‘When they struggle, I cannot sleep well either’: Perceptions and interactions surrounding university student and teacher wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.578378

Lynch, D., Yeigh, T., Woolcott, G., Peddell, L., Hudson, S., Samojlowicz, D., Markopolous, C., Bui, V., & Willis, R. (2020). An innovative teacher of mathematics identity framework: An adaptive solution to systematic challenges facing teachers in regional, rural and remote Australia. Australian Mathematics Education Journal, 2(3), 16–22.

Mansfield, C., & Gu, Q. (2019). “I’m finally getting that help that I needed”: Early career teacher induction and professional learning. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(4), 639–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00338-y

Markus, H. R., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41, 954–969. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954

McCallum, F., & Price, D. (2015). Teacher wellbeing. Nurturing wellbeing development in education: From little things, big things grow. (pp. 122–142). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315760834

Noble, T., McGrath, H., Roffey, S., & Rowling, L. (2008). Scoping study into approaches to student wellbeing. Australian Catholic University and Erebus International. https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/scoping_study_into_approaches

O’Connor, M., & Thomas, J. (2019). Australian secondary mathematics teacher shortfalls: A deepening crisis. AMSI. https://amsi.org.au/?publications=amsi-occasional-paper-2-australian-secondary-mathematics-teacher-shortfalls-a-deepening-crisis

Oishi, S., Choi, H., Buttrick, N., Heintzelman, S. J., Kushlev, K., Westgate, E. C., Tucker, J., Ebersole, C. R., Axt, J., Gilbert, E., Ng, B. W., & Besser, L. L. (2019). The psychologically rich life questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 81, 257–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.06.010

Oyserman, D., & Destin, M. (2010). Identity-based motivation: Implications for intervention. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(7), 1001–1043. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000010374775

Powell, M. A., & Graham, A. (2017). Wellbeing in schools: Examining the policy-practice nexus. The Australian Educational Researcher, 44(2), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-016-0222-7

Powell, M. A., Graham, A., Fitzgerald, R., Thomas, N., & White, N. E. (2018). Wellbeing in schools: What do students tell us? The Australian Educational Researcher, 45, 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0273-z

Quoidbach, J., Gruber, J., Mikolajczak, M., Kogan, A., Kotsou, I., & Norton, M. I. (2014). Emodiversity and the emotional ecosystem. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143, 2057–2066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.037

Renshaw, P. (2002). Learning and community. The Australian Educational Researcher, 29(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216761

Rowe, F., & Stewart, D. (2009). Promoting school connectedness: Using a whole-school approach. Health Education, 109(5), 396–413. https://doi.org/10.1108/09654280910984816

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2006). Best news yet on the six-factor model of wellbeing. Social Science Research, 35, 1103–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.01.002

Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning and teachers. The Future of Children, 27(1), 137–155.

Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press. https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=YVAQVa0dAE8C&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Flourish:+A+visionary+new+understanding+of+happiness+and+well-being&ots=de8LAhFU3V&sig=Fzf59Gf3aGTPiZjbowelnqQkLDg#v=onepage&q=Flourish%3A%20A%20visionary%20new%20understanding%20of%20happiness%20and%20well-being&f=false

Smylie, M. A., Murphy, J., & Louis, K. S. (2016). Caring school leadership: A multi-disciplinary, cross-occupational model. American Journal of Education. https://doi.org/10.1086/688166

Tamir, M., Schwartz, S. H., Oishi, S., & Kim, M. Y. (2017). The secret to happiness: Feeling good or feeling right? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146(10), 1448–1459. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000303

Topp, C. W., Østergaard, S. D., Søndergaard, S., & Bech, P. (2015). The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1159/000376585

Tunajek, S. (2019). Building wellness wealth. https://www.aana.com/docs/default-source/wellness-aana.com-web-documents-(all)/building-wellness-wealth.pdf?sfvrsn=ac2c4bb1_2

Vittersø, J. (2016). Handbook of eudaimonic wellbeing. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-42445-3.pdf

Wang, Z., Liu, H., Yu, H., Wu, Y., Chang, S., & Wang, L. (2017). Associations between occupational stress, burnout and wellbeing among manufacturing workers: Mediating roles of psychological capital and self-esteem. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 17(364), 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1533-6

Willis, A. S., & Grainger, P. R. (2020). Teacher wellbeing in remote Australian communities. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 45(5), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2020v45n5.2

Willis, R., Lynch, D., Peddell, L., Yeigh, T., Woolcott, G., Bui, V., Boyd, W., Ellis, D., Markopoulos, C., & James, S. (2021). Development of a teacher of mathematics identity (ToMI) scale. Mathematics Education Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-021-00391-w

Woolcott, G., Peddell, L., Yeigh, T., Willis, R., Markopoulos, C., Ellis, D., Lynch, D., & Bui, V. (2021). School reform in rural Australia: Developing adaptive solutions to systemic challenges for teachers of mathematics. In C. V. Meyers (Ed.), Rural school turnaround and reform: It’s hard work! (pp. 195–219). Information Age Publishing. https://www.infoagepub.com/products/Rural-School-Turnaround-and-Reform

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Funding was received from the Mathematical Association of New South Wales (MANSW) for the overall research project. MANSW did not influence what is reported herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and analysis were performed by Royce Willis, Tony Yeigh and David Lynch. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Tony Yeigh and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics statement

The research was approved by the Southern Cross University Human Research Ethics Committee #2021/092.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The figures 1 and 2 are corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yeigh, T., Willis, R., James, S. et al. Teacher of mathematics identity as a predictor of teacher wellbeing. Aust. Educ. Res. 50, 1403–1420 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00553-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00553-0