Abstract

Internationally, standard observational measures of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) are used to assess the quality of provision. They are applied as research tools but, significantly, also guide policy decisions, distribution of resources and public opinion. Considerable faith is placed in such measures, yet their validity, reliability and functioning within context should all be considered in interpreting the findings they generate. We examine the case of the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) in the Australian study, Effective Early Education for Children (E4Kids). Using this measure Australian educators were identified as “low quality” in provision of instruction (average 2.1 on a scale of 1–7). When these results became public, they attracted negative press coverage and the potential for harm. We interrogate these findings asking three questions relating to sampling, contextual and empirical evidence that define quality and measurement strategies. We conclude that measurement problems, most notably a floor effect, is the most likely explanation for uniformly low CLASS-Instructional scores among Australian ECEC educators, and indeed across international studies. Using a theoretically and empirically informed rescaling strategy we show that there is a diversity of instructional quality across Australian ECEC, and that rescaling might more effectively guide improvement strategies to target those of lowest quality. Beyond, our findings call for a more critical approach in interpretation of standard measures of ECEC quality and their applications in policy and practice, internationally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Complex statistical analyses of large-scale data collections are one of the many strategies we apply in our research team as we endeavour to inform policy and practice in early childhood education and care (ECEC). Such work can provide the big picture; an overview of ECEC functioning and effectiveness at national or jurisdiction level. However, like any other research strategy, this one has limitations and should be open to question. Importantly, the contribution of this form of research is inextricably linked to the faith we can place in the measures applied to collect data at-scale.

Large scale statistical work is dependent on measurement. When applied to understand the impact of ECEC on children’s development and learning, this means that qualities of the ECEC environment and their effects (e.g., change in children’s knowledge and skills) are quantified. Some measurements of quality are straight forward. Structural qualities of the ECEC environment, such as group size or educator to child ratios, are simple counts and typically not subject to dispute. Other measurement is less certain; both subject to judgements on the part of those who develop the measurement tools and to interpretation by those who observe ECEC environments and apply these tools of quantification (Gordon et al., 2021; Mantzicopoulos et al., 2018; Styck et al., 2020).

While there is agreement that interactions between children and adults in the ECEC context are central to children’s experiences (Being and Belonging) and learning outcomes (Becoming) (Australian Government Department of Education, 2019; Mashburn et al., 2008; Stronge, 2018; Thorpe et al., 2020a), quantifying interactional qualities and naming these as representations of quality, becomes contentious (Mantzicopoulos et al., 2018; Mashburn, 2017; Thorpe et al., 2020a, 2021). There is ongoing scholarly debate about whether ECEC quality should be measured relative to context or as a standard that transcends context and is applicable to all (Campbell-Barr & Bogatić, 2017; Hunkin, 2018; Jackson, 2015; Rentzou, 2017). Contextual factors that might influence how quality is defined, or how its elements are weighted, include two key sources of variation. First, variations in the cultural and community characteristics in which a service is sited may influence quality. These may determine the resources available, influence educational priorities and determine an appropriate educator response (Jackson, 2015; Rentzou, 2017). Interactions require child inputs and ‘quality’ is seen in responsiveness to the child (Justice et al., 2013). Children’s language, cognitive abilities, and behaviours, influence interactional possibilities (Coley et al., 2019; Houts et al., 2010). Second, the pervading pedagogical philosophy (Campbell-Barr & Bogatić, 2017; Hunkin, 2018) and specific pedagogical intent (Justice et al., 2013) within a teaching moment may direct interactional strategy and inform understandings of quality. Children are active agents and highly sensitive to educator’s cues (Bonawitz, 2011; Donaldson, 1978; Siegal, 2013). For example, experimental evidence shows that when presented with a novel object, direct instruction will focus a child’s attention solely on the demonstrated function and thereby limit exploration of other possibilities. In contrast, when presented with the same novel object without direct instruction a child exhibits greater exploration to identify multiple functions of the novel object (Bonawitz, 2011). Thus, if a pedagogical goal is to inculcate specific knowledge, direct instruction may well define quality. In contrast, if the intention is to support hypothesis testing, generate motivation for learning, or encourage creativity, then a problem-based learning approach may well define quality (Kuhn, 2007).

Despite ongoing debate, across the last two decades, commercialised, standard observation measures of ECEC environments have come to dominate assessment of ECEC and definitions of ECEC quality. Measures such as the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS) (Harms et al., 1998; Sylva et al., 2003) and the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) (Pianta et al., 2008) have been increasingly reified as synonymous with ECEC quality. They have been applied not only as research tools but have been trusted as accurate representations of ECEC quality and applied in critical policy and practice judgements that direct funding actions (Mashburn, 2017; Thorpe et al., 2020a) and influence public opinion (Marriner, 2012, 2016).

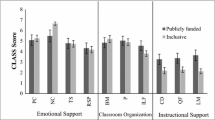

The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) (Pianta et al., 2008) has emerged as the most influential measure of ECEC quality in the last decade (Mashburn, 2017). CLASS measures three domains of quality: instructional support (CLASS-IS), classroom organisational (CLASS-CO) and emotional support (CLASS-ES). The content of each is outlined in Fig. 1. In the Australian context CLASS was the measure adopted by our research team to quantify educator-child interaction in the largest, published national study of ECEC quality, E4Kids (Tayler et al., 2016a, 2016b). E4Kids was designed to assess the effectiveness of Australia’s licensed ECEC services by tracking ongoing child development outcomes (2010–2015). In the first year of the study, a representative sample of 257 preschool, long day care and family day care rooms were observed. Of these, 225 rooms were observed for a minimum period of 80 min (4 cycles × 20 min). The findings, presented in Fig. 2, showed that while assessed emotional (CLASS-ES) and organisational (CLASS-CO) qualities of the ECEC rooms were, on average, in the satisfactory range (average scores of 5.13 and 4.6. respectively, on a 1–7 scale) instructional qualities (CLASS_IS) were in the low range (average 2.37) (Tayler et al., 2013; Tayler et al., 2016a, 2016b). When these results were first made public, newspaper headlines suggested that all Australia’s early childhood educators were “flunking the test” (Marriner, 2012). In this paper, we revisit the findings of low-quality instruction in Australian ECEC services. We commence with two stories: one of the fieldworkers undertaking CLASS observations in the E4Kids study and the other that of a researcher taking an alternative approach to understanding educator-child interactions in ECEC, applying conversation analysis (CA) methodology (Heritage, 2016; Sacks, 1995). We bring these two together to present a third story that calls into question the numbers deriving from CLASS-IS that asserted that Australian early childhood educators, on average, deliver poor quality teaching.

Story 1: what the observers saw

The assessment of interactional quality in E4Kids was an enormous task with more than 90 researchers collecting data across urban (Melbourne, Brisbane), regional (Shepparton, Victoria), and remote (Mt Isa, Queensland) Australian communities. The field work required direct observation of ECEC quality in each classroom using the CLASS measures in which there were cycles of 20-min of observation with a following 10-min coding period. Alongside, researchers spent many more hours present in the ECEC services as they undertook standard testing of each participating child’s cognition and learning. All field-researchers were trained in CLASS observation against master codes using proprietary, standard video-recorded classrooms (Teachstone Corporation, USA). All were certified as reliable by a certified trainer, and independently verified by Teachstone, USA. Across the data collections, field-researcher’s work was meticulously scrutinised to ensure fidelity with double scoring against a gold standard rater in the field. After their visits the researchers provided feedback both formally through standard report, but also informally in team meetings. A few times in their informal accounts the researchers reported observations of concern for the health or safety of children that required immediate follow-up by the study director. Sometimes they would comment on opportunities not taken (e.g., lack of discussion at mealtimes). Most times they would comment on educators doing their best under conditions of high demand. They also reported awe-inspiring moments of interactions between young children and their educators. When the summary statistics from analyses of thousands of observation cycles in early education settings were finalised, however, this variation was not captured. The results showed teaching interactions (CLASS-IS) did not reach the moderate range but, rather, were uniformly rated low. Those “awesome” moments reported by the researchers were not evident (Fig. 3). The scores suggested that even those awe-inspiring educators were, at best, rated as mediocre (low–mid range).

Story 2: what the PhD student discovered

Far from the application of standard assessment of ECEC quality, is the method of conversation analysis (CA) (Heritage, 2016; Sacks, 1995). In the ECEC context this method has been applied to undertake detailed analysis of interactions, examining unfolding moment-by-moment exchanges between educator and child. Conversation analysis is not a measure of quality but rather provides deep insight into how interactions are enacted and, in the context of ECEC, can identify strategies that engage children in ongoing conversation and opportunities for learning. In contrast to standard quantitative measurement that captures counts of pre-determined actions as indices of quality (e.g. “Teacher uses How and Why questions”—Pianta et al., 2008, p. 62), conversation analysis serves to uncover the qualities of interactions that serve to promote, or limit, learning.

In a Ph.D. study by one of the authors (Houen, 2017; Houen et al., 2016) conversation analysis was applied to understand how educators request factual information from children and how they invite children’s contributions to classroom discussions. Such dialogic interactions between educator and child have been identified in an extensive education literature as a marker of ECEC quality (e.g., Mashburn et al., 2008; OECD, 2019; Siraj‐Blatchford & Manni, 2008) and are included within the behavioural markers of quality in CLASS-IS (Pianta et al., 2008). The Ph.D. study undertook a fine-grained analysis of educator-child interactions captured within a corpus of 80 hours of teacher–child video recordings in ECEC settings. The findings challenged a long-held assertion, embedded within measures such as CLASS-IS that “open” questions (e.g. ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘why’) necessarily result in longer and deeper exchanges between educator and child (Siraj‐Blatchford & Manni, 2008), a challenge also noted in school contexts (Dillon, 2006). The analysis showed that these methods of questioning often positioned the educator as ‘knowing’ and the child as ‘tested’ with consequent closing down of conversation. In contrast, the use of phrases such as “I wonder…”, positioned the educator as ‘unknowing’ and equal partner in learning and were more likely to achieve extended interactions. However, the educator’s follow up responses were pivotal in providing children with opportunities for sustained discussions and co-constructed learning. Thus, the educators’ action of questioning (Pianta et al., 2008, p. 62) was not of itself a marker of quality but rather the ongoing contextualised response. Further, an important meta-finding was that these effective verbal moments of ‘wondering’ were only of a few minutes’ duration. Beyond, there were pauses for children to think and spaces for children to experiment, explore, discover, and act. Teacher talk, a defining element of CLASS-IS, was not of itself the essence of high-quality interaction, but only part of the picture. Important also was what happened in the spaces between.

Story 3: awesome or awful? Applying conversation-analysis to question assumptions underpinning standard measurement of instructional quality

Sometimes in quantitative research the numbers do not add up. The analyses deliver a score or a statistical finding that does not tally with expectation or logic. In these circumstances, while the finding may indeed be correct and new knowledge created, the data must be scrutinised to ensure that errors have not been made or that alternative explanations cannot be found. Given the power of numbers to influence policy and practice, such scrutiny is essential to avoid the potential of harm (Mashburn, 2017; Thorpe et al., 2020a, 2020b). The finding of uniformly low ‘instructional quality’ across the diversity of Australian ECEC provision was potentially harmful and did not add up in light of reports from the field-researchers. A focus on dialogic exchanges between child and educator, however, did fit with educational theory and empirical evidence that shows that such exchanges predict positive child outcomes (Mashburn et al., 2008; Siraj‐Blatchford & Manni, 2008). So, what was wrong? To investigate we asked three fundamental questions that interrogated the functioning of the CLASS-IS measure in context:

Question 1: were low CLASS-IS scores related to the Australian ECEC settings or the E4Kids sampling?

E4Kids was the first large-scale study of ECEC quality in Australia and the first international study to observe all forms of licensed ECEC provision, sampling across family day care, long day care and kindergarten programs. The low average CLASS-IS scores may reflect the greater diversity of settings observed in this study compared with others internationally. Yet, evidence suggests this was not the case. Looking within the Australian sample, we focussed on stand-alone Kindergarten programs as these have the most favourable conditions and should perform highest. Kindergarten programs are distinguished by having the oldest cohort of children, stable class groups attending shorter sessions, and generally more qualified staff. In these more optimal settings, as seen in Fig. 4, we still found that CLASS-IS was almost entirely in the low range.

Looking beyond the Australian context to compare our findings with those of several other nations (Fig. 5) we found low CLASS-IS scores are typical, regardless of where the data were collected, and the diversity of service types represented. In fact, an average upper range of scoring high quality, that is a score of 5–7, is not evidenced in any international context. Most notable are observations of Finnish Kindergarten settings, revered as representations of excellence in ECEC (Sahlberg, 2012, 2021; Sahlberg & Doyle, 2020; Taguma et al., 2012). In these settings, high-quality curriculum, exceptional levels of educator qualification (most with Masters degree) and older age of those attending (7 years) with commensurate higher verbal ability, all raise expectation of high CLASS-IS scores. Yet, average scores only enter the low-moderate range (mean = 3.7). The specific context of Australian ECEC, and the diversity of service types, therefore, did not explain the low scores.

Question 2: were low CLASS-IS scores related to a discrepancy in understanding of ECEC quality?

A discrepancy between the philosophical understanding of quality enacted in pedagogical practice in the Australian context and that underpinning the USA-developed CLASS-IS measure was a potential explanation as educators may be working to different goals. Yet this also seems unlikely. The three dimensions of CLASS-IS and their observational indicators (Fig. 1) have strong face validity. That is, they align with a view of instructional quality that places high levels of interaction between educator and child as central (Edwards, 2017; Mashburn et al., 2008; OECD, 2015, 2019). The content of CLASS-IS also aligns with specification of instructional quality within Australia’s National Quality Standards (Quality Area 1) (Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority, 2020) that asserts that a child should have agency in their learning.

Pedagogical intent (high levels of educational interaction) and the functioning of the CLASS-IS measure in practice might not align. Available evidence on how CLASS-IS functions in practice shows that high scores are generated in more formal instruction seen in whole group activities, literacy and numeracy content (Cabell et al., 2013; Thorpe et al., 2020a, 2020b). A measure that preferences whole group activity may not align with the predominating play-based pedagogical philosophy underpinning practice in Australian ECEC settings and explain the low scores seen in Australian ECEC. Yet this explanation does not adequately account for the findings for two reasons. First, in the school environment we still saw low scores. Over 4 years of tracking, E4Kids conducted observations in the children’s school aged classrooms (N = 2187), across Preparatory (n = 1500), Year 1 (n = 497), and Year 2 (n = 190). Comparison of the distribution of CLASS-IS observed across each grade, presented in Fig. 6, showed that while there was a slight increase in average CLASS-IS in the formal school years, where learning is typically more structured and programs are led by degree qualified teachers, the average observation score remained in the low range. Second, in Finnish classrooms where a strong play-based pedagogical approach predominates, we saw the highest scores across international comparisons. This finding suggests play-based approaches, of themselves, do not explain low scores.

Question 3: is there a measurement problem?

We asked whether the scaling of the measure was producing a floor effect, in which the possibility of obtaining a moderate CLASS-IS score was unlikely; and that of obtaining a high score infeasible. Our next step was to investigate that possibility.

The detail of conversation analysis within the ECEC setting provided a clear direction to understand why a floor effect may emerge in measurement of CLASS-IS. Like the other two domains of CLASS (CLASS-CO, CLASS-ES), scoring of CLASS-IS is based on observation cycles of 20-min following which educator behaviours across the entire observation period are scored. To obtain a high score on CLASS-IS for each cycle, therefore, requires instructional language exchanges between child and educator for the majority of each 20-min observation. Furthermore, to achieve high average CLASS-IS scores across the total observation of 4–6 cycles would require a continually high level of verbal instruction across a 2–3-h period. Using this scoring procedure there are two distinct reasons that explain the low likelihood of scores in the higher range on CLASS-IS. First, the expectations are unrealistic. Across a 2–3-h period in ECEC settings the imperative for care activities (meals, toileting) and transitions between activities reduces the possibility of continual instructional exchange. Second, the expectations may be suboptimal. Houen’s detailed analysis (Houen, 2017; Houen et al., 2016) suggests long verbal exchanges that comprise most of a 20-min observation cycle are inconsistent with a play-based pedagogical approach. Yet play-based pedagogy is recommended, both as an age-appropriate approach (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2020; Edwards, 2017; Flückiger et al., 2018; Fluckiger et al., 2017) and as a marker of high quality in early education (Sahlberg, 2021; Sahlberg & Doyle, 2020; Taguma et al., 2012). Within a play-based approach, reciprocal verbal exchanges interspersed with spaces for thinking and acting would be expected. For example, the Learning Language and Loving It program (Weitzman & Greenberg, 2002) recommends teachers engage in a minimum of four turns when interacting with children and also encourage peer to peer interaction. The teacher input in these exchanges would take a few minutes, not the majority of a 20-min cycle. Thus, the instructional domain (CLASS-IS) contrasts with the emotional (CLASS-ES) and organisational (CLASS-CO) domains in rating behaviours that are necessarily and appropriately intermittent, not continual. CLASS-IS counts content-events, with high weighting on teacher talk, (80% of behavioural indicators in CLASS-IS manual) but low weighting on child inputs (20% of behavioural indicators relate to “student” actions). Continual rating, therefore, fails to capture non-verbal educator actions (e.g., providing pauses and spaces) and does not adequately capture child inputs.

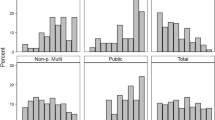

Houen’s analysis (Houen, 2017; Houen et al., 2016) suggests the problem of scaling relates to the expectation of continuous rather than interspersed exchange; of focus on the density of educator inputs rather than the dispersal of exchanges that afford child agency and encourage child input into interactions. Indeed, this is true not only in ECEC contexts. Studies of learning in more formal school settings indicate that the period of instruction and the activities in between (opportunities for reflection, self-directed application) are both necessary for deep learning (Dillon, 2006). Applying this logic, we trialled a rescaling of E4Kids data taking the highest level of exchange rather than the average across time. In so doing we removed the assumption that continual exchange was optimal. The result of the rescaling is presented in Fig. 7.

The rescaled CLASS-IS served not only to shift scores into the moderate range but also redistributed scores as those educators providing space for child actions were less likely to be penalised by the scoring system. The resulting distribution was more consistent with reports of our fieldworkers. A few rooms were indeed providing no or low levels of instructional verbal interaction across a period of 1–3 h, many were providing moderate levels of educational exchanges in that time and an “awesome’’ few were scoring at the highest levels. Taking this scaling we then compared patterns across the transition from ECEC setting through Preparatory, Year 1 and Year 2 classrooms using the same E4Kids sample. The results, presented in Fig. 8, show that most CLASS-IS scores, when rescaled were no longer low but within the moderate range. Increases in CLASS-IS occurred more distinctly beyond the ECEC year consistent with changes in staff qualification (educators are now uniformly degree qualified teachers) and increasing verbal ability of children. Most notable in the trend across school years is the increased scores at Preparatory year consistent with greater consistency of teacher qualification (all degree qualified) increased focus on intentional teaching and previously reported biases of CLASS-IS to whole group formats and literacy and numeracy content.

Discussion

Developing observation measures of ECEC practice is a difficult task that demands a valid representation of ‘quality’; that can be reliably collected in large numbers; and that can accurately capture variability of practice. In examining the case of CLASS, we acknowledge the importance of this measure, and similar such standard measures. Collectively, large scale standard measures of ECEC quality have drawn attention to the conceptualisation of ECEC quality, undertaken detailed work in measure development and facilitated large scale research endeavours. Nevertheless, our questioning of potential issues with such measures when “something does not seem right with the results” is important. Questioning contributes to refinement; both of the target behaviour being measured (validity—does CLASS-IS align with conceptualisations of ECEC quality?) and of the methods by which these behaviours are measured (reliability—is the measurement replicable and representative?). Faith in statistical findings without questioning of the underpinning principles of measurement can misdirect policy decisions and practice actions (Hunkin, 2018; Mashburn, 2017; Roberts-Holmes, 2015; Thorpe et al., 2020a) or undermine public trust (Marriner, 2012).

Internationally, considerable energy and resource has been expended in remediating the perceived deficit in early childhood educator pedagogical skills with little effect (Egert et al., 2018; Pianta et al., 2016). Our questioning of the measurement of in CLASS-IS directs attention to underpinning assumptions about instructional quality in early childhood settings. Our findings based on rescaled CLASS-IS likely delivers a more accurate understanding of the diverse enactment of instruction in Australian settings (NQS Quality area 1) and should be a catalyst for questioning in other settings internationally.

Representing ECEC quality: learning from the example of CLASS—Instructional Support

Our analysis of CLASS-IS raises critical questions about intent and values in measuring ECEC quality through use of standard measures that are applied without adjustment for context. The intent of a standard measure is to allow absolute comparison. The value of absolute comparison should be to identify inequities and redress these through policy and practice actions. The danger of absolute comparison is the possibility of misunderstanding or misuse. In the case of low CLASS-IS scores, the value has been in directing focus on instructional elements of the ECEC environment, but the cost has been a labelling of all educators as “flunking the test” (Marriner, 2012) and assuming that there is a uniform deficit in educator skill. Most importantly, the biggest risk is reification of CLASS-IS scores that directs attention to educator deficit without considering the contexts of community or child in interpretation of scores. While CLASS-IS items have strong face validity, aligning with current research that places value on educationally focussed exchanges between child and educator, in practice CLASS-IS places extremely high weighing on the content of the educator’s inputs. Thus, the possibility of scoring highly in a community where children have lower language levels (Coley et al., 2019) (or language other than those used in assessment) or higher behavioural difficulties (Houts et al., 2010) is more limited. In these circumstances a focus on generalised educator deficit may misdirect policy and practice actions to focus on standard educator professional development rather than tailored educator supports to meet contextual needs. Further, other forms of resource such as improved staff ratios and/or specialised assistance (e.g., specialised expertise in behavioural or emotional problems) for educators or families may serve to enable higher rates of interaction and educational content.

To understand the value of a measure and the various components from which it is comprised, one important test is predictive validity; that is, whether the measure maps to an intended outcome. In the case of CLASS-IS we would predict (and intend) that scores would be associated with child learning and development outcomes. Analysing E4Kids data, we have examined the association of CLASS scores with concurrent, short-term (to age 8) and long-term (to age 14) child outcomes controlling for potential confounders (e.g., family background). Consistent with other such analyses (Egert et al., 2018; Hong et al., 2019; Perlman et al., 2016), we found weak prediction of CLASS, generally, and of CLASS-IS specifically (2020b). Nevertheless, when we applied the strongest test, long-term prediction, interesting outcomes emerged. Using data linkage of CLASS domain and dimension scores at age 3–4 years to school records across ages 5–14 years showed that while the CLASS-IS domain does not reliably predict child outcomes, one of the three Instructional Support dimensions, quality of feedback, predicts achievement in numeracy, literacy, and science across time (Thorpe et al., 2020b). Alongside, the emotional domain, CLASS-ES, and its dimension, the dimension regard for student perspective emerged as a predictor. Together these findings suggest that it is not the content (concept development and language modelling) but the process of interacting with children that has enduring effect, with child inputs and educator responses a significant component of quality. This being the case, attention to the scaling of the CLASS-IS to adjust underlying assumptions of continual rather than interspersed input becomes particularly meaningful. Such an adjustment captures the affordance of space for child inputs and, thereby better captures educator-child interaction, not simply educator action.

Measuring Instructional quality: learning by questioning CLASS-Instructional Support

Our analysis of CLASS-IS raises critical questions about procedures in measuring ECEC quality that relate to reliability of the measure. The protocols for measuring ECEC quality using CLASS are well-developed. There are stringent training regimes and tests of reliability to ensure maintenance of fidelity to the observation strategy. We note some concerns have been raised about the standard reliability criterion set by the developers and about rater-bias effects (Styck et al., 2020). Reliability in CLASS does not require exact agreement between gold standard codes but rather deems an observer as reliable if they are within 1 score (plus or minus) of the master code. This procedure manifests in reduction of scale usage with an observer unlikely to use the extreme codes (1 and 7). Addressing this issue, however, is outside the remit of this paper. In E4Kids we adopted the standard training and reliability protocols. Considerable effort was expended to ensure ongoing fidelity to the codes. As data collection proceeded, reliability checks occurred against both master-coded video-recordings and a master-coder in the field. Additionally, weekly checks of codes against field notes were undertaken. Our results, therefore, are a true representation of the CLASS measure as intended by the developers (Pianta et al., 2008).

A true representation of a measure, however, may not be a true representation of ECEC quality. In the case of CLASS-IS, our analysis suggests the measure may work to under-represent some aspects of ECEC quality, namely child inputs into interactions, and fail to adequately distinguish variability. We argue that while it is pragmatic to measure all three domains of CLASS on the same scale based on a rate/time, the perverse effect is to create a floor effect, reduce variability and represent ECEC instructional quality as uniformly low. Our simple rescaling likely presents a more accurate and useful focus for exploring the associations with child outcomes and targeting interventions.

Interpreting the meaning of findings of low instructional quality for policy and practice

Our analysis of CLASS-IS has three key implications for ECEC, both in the specific context of Australia and internationally.

First and most important, our rescaling of CLASS more likely provides a more accurate picture of the quality of educational experiences provided to Australian children across the diversity of ECEC services. Our analysis refutes the claim that Australian ECEC educators are uniformly of low quality. Rather, our results suggest there is a diversity of quality and, on average, moderate levels of instruction. While there is certainly room for quality improvement, not all educators are failing our children as suggested in the headlines of 2012 (Marriner, 2012). Understanding the functioning of the measure and applying rescaling might increase precision in directing resources to those services and educators most in need of supports to improve interactional quality. Consideration of the context in which these scores were generated might direct policy and practice responses to be more effective.

Second, our analysis provides direction for improving instruction across the diversity of the ECEC day. In our analyses, Quality of Feedback has emerged as a positive predictor of long-term education outcomes (Thorpe et al., 2020b). This dimension of CLASS-IS focusses on the educator’s response to child input rather than educator-initiated input, assessing “the degree to which a teacher provides feedback that expands learning and understanding and encourages continued participation” (Pianta et al., 2008, p. 69). Consistent with Houen’s research (Houen, 2017; Houen et al., 2016), this dimension of instruction focusses on child inputs and child agency as a learner, not educator directed content (concept development) or language (language modelling) alone. A focus on engaging children as active agents in learning conversations is identified as a key focus for professional development to improve ECEC quality, and is one identified by Evidence for Learning Australia who have recently developed teacher resources based on a systematic review of Australasian evidence (Houen et al., 2019; Evidence for Learning, 2020). Importantly, the opportunity for child-led learning activity is more likely to occur outside the whole group format, yet the evidence available suggests this is where higher CLASS-IS scores are achieved. One key focus, therefore, might be activities and times of day when evidence shows that opportunities for educational exchanges are least likely to happen. For example, mealtimes score very low in instructional quality yet present important opportunities for such educational interactions (Thorpe et al. Thorpe, Rankin, et al., 2020).

Third, current studies of CLASS utilise the standard CLASS-IS measure that we originally applied in E4Kids. This is scored as a rate/time and therefore has the implicit assumption that density of educator input equates to quality. The greater variability in the rescaled measure that removes this assumption may serve to increase the predictive validity of the measure as it more finely discriminates between ECEC experiences with a range of 1–7 compared with a range of 1–5 (Styck et al., 2020). While other conceptualisations and methods of assessing instructional quality may better discriminate quality, for those studies that have already used or that choose to use CLASS applying the rescaling approach may offer a valuable additional approach in analyses.

Conclusion

We conclude that while the CLASS measure and other such measures have a place as a research instrument in assessing ECEC quality, the underlying assumptions should be rigorously examined, and potential limitations acknowledged. Questioning standard measures that quantify ECEC quality, is a key part of responsible interpretation of research results and an essential prior step before advancing to subsequent policy and practice actions.

Data availability

Data from E4Kids and KWEB are available through respective administrative Universities: E4Kids (The University of Melbourne) and KWEB (Queensland University of Technology.

Code availability

Available from authors on request.

References

Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority. (2020). Guide to the National Quality Framework. Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority.

Australian Government Department of Education, Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. (2019). Belonging, being & becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia. Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

Bonawitz, E., Shafto, P., Gweon, H., Goodman, N. D., Spelke, E., & Schulz, L. (2011). The double-edged sword of pedagogy: Instruction limits spontaneous exploration and discovery. Cognition, 120(3), 322–330.

Cabell, S. Q., DeCoster, J., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2013). Variation in the effectiveness of instructional interactions across preschool classroom settings and learning activities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(4), 820–830.

Campbell-Barr, V., & Bogatić, K. (2017). Global to local perspectives of early childhood education and care. Early Child Development and Care, 187(10), 1461–1470.

Coley, R. L., Spielvogel, B., & Kull, M. (2019). Concentrated poverty in preschools and children’s cognitive skills: The mediational role of peers and teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 76, 1–16.

Dillon, J. (2006). Effect of questions in education and other enterprises. In I. Westbury & G. Milburn (Eds.), Rethinking schooling (pp. 145–174). Routledge.

Donaldson, M. (1978). Children’s minds (Vol. 5287). Fontana London.

Edwards, S. (2017). Play-based learning and intentional teaching: Forever different? Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(2), 4–11.

Egert, F., Fukkink, R. G., & Eckhardt, A. G. (2018). Impact of in-service professional development programs for early childhood teachers on quality ratings and child outcomes: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 88(3), 401–433.

Evidence for Learning. (2020). Evidence-informed oral language resources. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/evidence-informed-educators/early-childhood-education/oral-language-resources/

Flückiger, B., Dunn, J., & Stinson, M. (2018). What supports and limits learning in the early years? Listening to the voices of 200 children. Australian Journal of Education, 62(2), 94–107.

Fluckiger, B. R., Dunn, J., Stinson, M., & Wheeley, E. (2017). Leading age-appropriate pedagogies in the early years of school. Paper presented at the Research Conference 2017—Leadership for Improving Learning—Insights from Research. https://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference/RC2017/29august/3. Accessed 2 Oct 2021.

Gordon, R. A., Peng, F., Curby, T. W., & Zinsser, K. M. (2021). An introduction to the many-facet Rasch model as a method to improve observational quality measures with an application to measuring the teaching of emotion skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 55, 149–164.

Harms, T., Clifford, R. M., & Cryer, D. (1998). Early childhood environment rating scale. ERIC.

Heritage, J. (2016). Conversation analysis: Practices and methods. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research: Theory, method, and practices (4th ed., pp. 207–224). Sage.

Hong, S. L. S., Sabol, T. J., Burchinal, M. R., Tarullo, L., Zaslow, M., & Peisner-Feinberg, E. S. (2019). ECE quality indicators and child outcomes: Analyses of six large child care studies. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 49, 202–217.

Houen, S. L. (2017). Teacher talk: “I wonder…” Request designs. Queensland University of Technology.

Houen, S., Danby, S., Farrell, A., & Thorpe, K. (2016). ‘I wonder what you know…’teachers designing requests for factual information. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 68–78.

Houen, S., Staton, S., Coles, L., Van Os, D., Westwood, E., Bayliss, O., et al. (2019). Supporting Rich Conversations with Children aged 2–5 years in Early Childhood Education and Care within Australasian Studies. Evidence for Learning.

Houts, R. M., Caspi, A., Pianta, R. C., Arseneault, L., & Moffitt, T. E. (2010). The challenging pupil in the classroom: The effect of the child on the teacher. Psychological Science, 21(12), 1802–1810.

Hunkin, E. (2018). Whose quality? The (mis) uses of quality reform in early childhood and education policy. Journal of Education Policy, 33(4), 443–456.

Jackson, J. (2015). Embracing multiple ways of knowing in regulatory assessments of quality in Australian early childhood education and care. The Australian Educational Researcher, 42(4), 515–526.

Justice, L. M., McGinty, A. S., Zucker, T., Cabell, S. Q., & Piasta, S. B. (2013). Bi-directional dynamics underlie the complexity of talk in teacher–child play-based conversations in classrooms serving at-risk pupils. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(3), 496–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.02.005

Kuhn, D. (2007). Is direct instruction an answer to the right question? Educational Psychologist, 42(2), 109–113.

Leyva, D., Weiland, C., Barata, M., Yoshikawa, H., Snow, C., Treviño, E., & Rolla, A. (2015). Teacher–child interactions in Chile and their associations with prekindergarten outcomes. Child Development, 86(3), 781–799.

Mantzicopoulos, P., French, B. F., Patrick, H., Watson, J. S., & Ahn, I. (2018). The stability of kindergarten teachers’ effectiveness: A generalizability study comparing the framework for teaching and the classroom assessment scoring system. Educational Assessment, 23(1), 24–46.

Marriner, C. (2012). Preschools flunk the test. Retrieved from https://www.illawarramercury.com.au/story/942912/preschools-flunk-the-test/. Accessed 2 Oct 2021.

Marriner, C. (2016). Children are better at maths if they don’t go to preschool: Study. Retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/national/children-are-better-at-maths-if-they-dont-go-to-preschool-study-20160129-gmgz03.html. Accessed 2 Oct 2021.

Mashburn, A. J. (2017). Evaluating the validity of classroom observations in the head start designation renewal system. Educational Psychologist, 52(1), 38–49.

Mashburn, A. J., Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., Barbarin, O. A., Bryant, D., et al. (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development, 79(3), 732–749.

OECD. (2015). Starting strong IV: Monitoring quality in early childhood education and care. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019). Providing quality early childhood education and care: Results from the starting strong survey 2018. OECD Publishing, Berlin.

Perlman, M., Falenchuk, O., Fletcher, B., McMullen, E., Beyene, J., & Shah, P. S. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of a measure of staff/child interaction quality (the classroom assessment scoring system) in early childhood education and care settings and child outcomes. PLoS ONE, 11(12), e0167660.

Pianta, R., Downer, J., & Hamre, B. (2016). Quality in early education classrooms: Definitions, gaps, and systems. The Future of Children, 26, 119–137.

Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom Assessment Scoring System™: Manual K-3. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Rentzou, K. (2017). Using rating scales to evaluate quality early childhood education and care: Reliability issues. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(5), 667–681.

Roberts-Holmes, G. (2015). The ‘datafication’of early years pedagogy: ‘If the teaching is good, the data should be good and if there’s bad teaching, there is bad data.’ Journal of Education Policy, 30(3), 302–315.

Sacks, H. (1995). Lectures on conversation (Vol. I–II). Wiley-Blackwell.

Sahlberg, P. (2012). A model lesson: Finland shows us what equal opportunity looks like. American Educator, 36(1), 20.

Sahlberg, P. (2021). Finnish lessons 3.0: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? Teachers College Press.

Sahlberg, P., & Doyle, W. (2020). Let the children play: For the learning, well-being, and life success of every child. Oxford University Press.

Salminen, J., Lerkkanen, M. K., Poikkeus, A. M., Pakarinen, E., Siekkinen, M., Hännikäinen, M., et al. (2012). Observed classroom quality profiles of kindergarten classrooms in Finland. Early Education & Development, 23(5), 654–677.

Siegal, M. (2013). Knowing children: Experiments in conversation and cognition. Psychology Press.

Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Manni, L. (2008). ‘Would you like to tidy up now? An analysis of adult questioning in the English Foundation stage. Early Years, 28(1), 5–22.

Stronge, J. H. (2018). Qualities of effective teachers. Alexandria, VA: ASCD press.

Styck, K. M., Anthony, C. J., Sandilos, L. E., & DiPerna, J. C. (2020). Examining rater effects on the Classroom Assessment Scoring System. Child Development, 92(3), 976–993. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13460

Sylva, K., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2003). Assessing quality in the early years: Early childhood environment rating scale: Extension (ECERS-E), four curricular subscales. Trentham Books.

Taguma, M., Litjens, I., & Makowiecki, K. (2012). Quality matters in early childhood education and care. Finland. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/quality-matters-in-early-childhood-and-education-finland-2012_9789264173569-en. Accessed 2 Oct 2021.

Tayler, C., Cloney, D., Adams, R., Ishimine, K., Thorpe, K., & Nguyen, T. K. C. (2016). Assessing the effectiveness of Australian early childhood education and care experiences: Study protocol. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–12.

Tayler, C., Ishimine, K., Cloney, D., Cleveland, G., & Thorpe, K. (2013). The quality of early childhood education and care services in Australia. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(2), 13–21.

Tayler, C., Thorpe, K., Nguyen, C., Adams, R., Ishimine, K., Ferguson, A., et al. (2016). The E4Kids study: Assessing the effectiveness of Australian early childhood education and care programs. Melbourne University.

Thorpe, K., Potia, A.H., Beatton, T., Rankin, P., & Staton, S (2020b). Educational outcomes of Queensland’s investment in early childhood education and care (2007–2020b). Report to Queensland Government under the Education Horizon Grantt scheme. Brisbane December 2020.

Thorpe, K., Rankin, P., Beatton, T., Houen, S., Sandi, M., Siraj, I., & Staton, S. (2020a). The when and what of measuring ECE quality: Analysis of variation in the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) across the ECE day. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 274–286.

Thorpe, K., Westwood, E., Jansen, E., Menner, R., Houen, S., & Staton, S. (2021). Working towards the Australian National Quality Standard for ECEC: What do we know? Where should we go? The Australian Educational Researcher, 48, 1–21.

Von Suchodoletz, A., Fäsche, A., Gunzenhauser, C., & Hamre, B. K. (2014). A typical morning in preschool: Observations of teacher–child interactions in German preschools. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 509–519.

Weitzman, E., & Greenberg, J. (2002). Learning language and loving it: A guide to promoting children’s social, language, and literacy development in early childhood settings (2nd ed.). The Hanen Centre.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted at the University of Queensland using data from the Effective Early Education for Children (E4Kids) study under license from the University of Melbourne. E4Kids was funded by the Australian Research Council Linkage Projects Scheme (LP0990200), in collaboration with the Victorian Government Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, and the Queensland Government Department of Education and Training. The authors thank the ECEC services, directors, teachers/staff, children and their families who participated in E4Kids. Data Linkage from E4Kids to school outcomes, cited in the discussion of this paper, was facilitated through the Queensland, Department of Education and funded through an Education Horizon Grant from the Queensland Government. We thank the department for enabling this valuable work. Dr Sandra Houen conducted her Ph.D. studies of educator-child interactions using data from the Interacting with knowledge, interacting with people: Web searching in early childhood (KWEB) at the Queensland University of Technology. KWEB was funded by the Australian Research Council under the Discovery Program (DP110104227)- to Professor Susan Danby, professor Karen Thorpe and Dr Christina Davidson. We thank the teachers, children, and families of C&K, Queensland who participated in KWEB.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This paper contains data based on funding from two projects undertaken with funding from the Australian Research Council—E4Kids (LP0990200) and KWEB (DP110104227) and work pertaining to predictive validity was funded through a Queensland Government, Department of Education, Education Horizon Grant. Analyses of data was funded through funds provided through the ARC Centre of Excellence for Children and Families across the Life Course (CE200100025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KT—conceived of the article, was a CI on the funded studies on which this article draws, undertook analysis and writing of the article. SH—undertook analyses of educator-child interactions that informed conceptualisation and data provided in this paper, supported writing of the manuscript and undertook manuscript reviews. CP—supervised the E4Kids field work team, provided data relevant to the experiences of fieldworkers and contributed to manuscript review. PR—Undertook data analysis, made contribution to the original manuscript and undertook manuscript review. SS—made contribution to the conceptualisation, original manuscript and manuscript review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

E4Kids data were collected under respective ethics approvals at the University of Melbourne (Id. No. 09-3260) and Queensland University of Technology (Id 1000000172). KWEB data were collected under approval from Queensland University of Technology (ID No.: 1100001480).

Consent to participate

All participants consented to participate within the conditions of the Australia National Ethics Agreement framework as approved through respective University Human Ethics Research Committees.

Consent for publication

None required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thorpe, K., Houen, S., Rankin, P. et al. Do the numbers add up? Questioning measurement that places Australian ECEC teaching as ‘low quality’. Aust. Educ. Res. 50, 781–800 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00525-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00525-4