Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to evaluate if positron emission tomography (PET)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with just one gradient echo sequence using the body coil is diagnostically sufficient compared with a standard, low-dose non-contrast-enhanced PET/computed tomography (CT) concerning overall diagnostic accuracy, lesion detectability, size and conspicuity evaluation.

Methods and materials

Sixty-three patients (mean age 58 years, range 19–86 years; 23 women, 40 men) referred for either staging or restaging/follow-up of various malignant tumours (malignant melanoma, lung cancer, breast cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, CUP, gynaecology tumours, pleural mesothelioma, oesophageal cancer, colorectal cancer, stomach cancer) were prospectively included. Imaging was conducted using a tri-modality PET/CT-MR set-up (full ring, time-of-flight Discovery PET/CT 690, 3 T Discovery MR 750, both GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). All patients were positioned on a dedicated PET/CT- and MR-compatible examination table, allowing for patient transport from the MR system to the PET/CT without patient movement. In accordance with RECIST 1.1 criteria, measurements of the maximum lesion diameters on CT and MR images were obtained. In lymph nodes, the short axis was measured. A four-point scale was used for assessment of lesion conspicuity: 1 (>25 % of lesion borders definable), 2 (25–50 %), 3 (50–75 %) and 4 (>75 %). For each lesion the corresponding anatomical structure was noted based on anatomical information of the spatially co-registered PET/CT and PET/MRI image sections. Additionally, lesions were divided into three categories: “tumour mass”, “lymph nodes” and “lesions”. Differences in overall lesion detectability and conspicuity in PET/CT and PET/MRI, as well as differences in detectability based on the localisation and lesion type, were analysed by Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Results

A total of 126 PET-positive lesions were evaluated. Overall, no statistically significant superiority of PET/CT over PET/MRI or vice versa in terms of lesion conspicuity was found (p = 0.095; mean score CT 2.93, mean score MRI 2.75). A statistically significant superiority concerning conspicuity of PET/CT over PET/MRI was found in pulmonary lesions (p = 0.016). Additionally, a statistically significant superiority of PET/CT over PET/MRI in “lymph nodes” regarding lesion conspicuity was also found (p = 0.033). A higher mean score concerning bone lesions were found for PET/CT compared with PET/MRI; however, these differences did not achieve statistical significance.

Conclusion

Overall, PET/MRI with body coil acquisition does not match entirely the diagnostic accuracy of standard low-dose PET/CT. Thus, it might only serve as a back-up solution in very few patients. Overall, more time needs to be invested on the MR imaging part (higher matrix, more breath-holds, additional surface coil acquired sequences) to match up with the standard low-dose PET/CT.

Main Messages

• Evaluation of whether PET/MRI with one sequence using body coil is diagnostically sufficient compared with PET/CT

• PET/MRI with body coil does not match entirely the diagnostic accuracy of standard low-dose PET/CT

• PET/MRI might only serve as a backup solution in patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Integrated positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) has evolved into a mainstay of oncological imaging over the last decade [1–5]. The interest to integrate PET with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a similar way has increased recently and simultaneous PET/MRI or sequential PET/CT-MR systems potentially open new perspectives in clinical molecular imaging [6–13]. Superior soft tissue contrast of MRI compared with CT and less radiation exposure are the most obvious advantages of a simultaneous system. Other potential improvements—not yet proven in clinical trials—of PET/MRI over co-registered PET/CT includes the detection and localisation of liver metastases, detection and characterisation of gynaecological tumours as well as head and neck cancers [6, 7, 14]. Vice versa, PET/CT still have advantages in lesion detection and characterisation, for example, in bone lesions and lung tumours [15–17]. Several technical and clinical issues (e.g. sequence selection, clinical indications and workflow considerations, to name a few) have to be addressed before PET/CT can potentially be replaced by PET/MRI. Clinical MR imaging in oncology indications is mainly focused on one body region, while PET/CT imaging is usually performed as whole-body imaging. However, since PET/MRI should measure up to PET/CT, several controversies are currently being debated in the literature concerning the clinical imaging protocol [14, 18, 19]. In clinical routine, MRI is usually done with surface coils to achieve sufficient resolution as well as signal intensity. Also, CT imaging is usually done with sufficient dose and contrast media. However, those rules partly do not apply for PET/CT imaging, since the PET component already provides the main characteristics of the evaluated lesion. Therefore, even if in normal clinical routine body-coil imaging alone is certainly not adequate to achieve sufficient image quality, there might be a clinical situation in multi-modality imaging where it might be desirable to have a quick whole-body PET/MRI—e.g. in patients with severe claustrophobia, in patients who had to be imaged as quickly as possible based on medical conditions or in cases of technical (surface-coil) failure. In those situations, it might be enough to have PET/MRI—even only with a body coil—to achieve a sufficient diagnosis.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to evaluate if PET/MRI imaging with just one sequence using a body coil—which is the minimum acquired sequence because it is needed for MRAC—can measure up to a standard, low-dose non-contrast-enhanced PET/CT in the above-mentioned clinical scenarios.

Materials and methods

Patient population

A total of 63 adult patients (mean age 58 years, range 19–86 years; 23 women, 40 men) referred for either staging or restaging/follow-up of various malignant tumours participated in this prospective study (Table 1). Inclusion criteria were a clinically indicated whole-body 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG)-PET/CT and willingness to participate in the additional MRI with subsequent shuttle procedure. Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to undergo an additional MR exam, claustrophobia, MR incompatible implanted medical devices (e.g. cardiac pacemakers, insulin pumps, neurostimulators, cochlear implants), possible metallic fragments in the body or a body habitus that did not fit into the MR gantry together with the mounted shuttle board. This study was approved by the local ethical committee and written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to the investigation.

Imaging modalities

Sequential PET/CT and MR imaging were performed on a tri-modality PET/CT + MR setup (full ring, time-of-flight Discovery PET/CT 690, 3 T Discovery MR 750; both GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). All patients were positioned on a dedicated PET/CT- and MR-compatible examination table, allowing for patient transport from the MR system to the PET/CT and placement/removal of dedicated radiofrequency (RF) coils without repositioning/movement of the patient [20].

PET/CT

Patients fasted for at least 4 h prior to injection of a standard dose with a mean activity of 334 MBq of 18F-FDG. After a standardised uptake time of 60 min (range 52–74 min) unenhanced low dose CT and PET emission data were acquired from the mid-thigh to the vertex of the skull. CT data were acquired with automated dose modulation (maximal 100 mA) 120 kVp, a collimation of 64 × 0.625 mm, a measured field of view (FOV) of 50 cm, a noise index of 20 %, reconstructed to images of 0.625-mm transverse pixel size and 3.75-mm slice thickness. PET data was acquired in 3D mode with scan duration of 2 min per bed position and an axial FOV of 153 mm. The emission data was corrected in a standardised way (random, scatter and attenuation) and iteratively reconstructed (matrix size, 256 × 256, Fourier rebinning [VIP mode], VUE Point FX [3D] with 3 iterations, 18 subsets). Patients were already positioned on the dedicated shuttle board within the PET/CT-system.

MR imaging

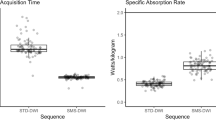

After the PET/CT, patients were transferred via a dedicated shuttle system to the MRI while remaining on the shuttle board. A whole-body multi-section MR scan was acquired. An axial two-point Dixon-based T1-weighted 3D gradient echo sequence (LAVA flex) was acquired and fat-suppressed images were reconstructed for all stations. Additionally, images without fat suppression as well as in-phase and opposed-phase images were reconstructed. All FOVs were acquired axially for routine clinical evaluation (TE/TR 1.8/3.9 ms, slice thickness 6.8 mm, total MR acquisition time 128–144 s). Coverage was 25 cm, imaging was done in breath-hold for breathing-sensitive areas (thorax/abdomen). No other planes of orientation or sequences were acquired for this study. No contrast medium was applied during MRI. No dedicated RF coils were positioned on the patient to perform body coil imaging only.

Image processing

The acquired PET, CT and MR images were sent to a dedicated review workstation (Advantage Workstation, Version 4.6; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI), which allows for simultaneous review of the PET, CT, MRI as well as PET/CT and PET/MRI images. The workstation layout allows for dedicated fused views of all modalities side-by-side.

Image analysis

Images were analysed by one dual-board-certified radiologist/nuclear medicine physician with 6 years of experience and one board-certified radiologist with 7 years of experience. Reading of PET/CT and PET/MRI scans were done independently and blinded to the results of the other reader. First, the PET/CT exams and the PET/MRI exams were evaluated for the presence of PET-positive and PET-negative (suspicious for tumour) lesions. Lesions were considered PET-positive if their standardised uptake value (SUV; corrected for body weight and height) was distinctively higher than the surrounding background activity. The threshold value of the maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) was manually adjusted for each lesion. By this adjustment, the volume of interest (VOI) delineates only the borders of the tumour based on its PET-activity. Up to 11 PET-positive lesions were evaluated per patient with a maximum of two lesions per single organ/compartment (see below). In patients with multiple lesions in the same organ (e.g. disseminated liver metastases) the largest lesions and lesions that were clearly distinguishable from each other were selected for analysis. Lesion detection and evaluation were done independently by each reviewer. After full and independent evaluation of all lesions in PET/CT and in PET/MRI, lesion selection was compared between both readers. In case of differently chosen lesions on PET/CT or PET/MRI, both readers agreed upon which lesion finally were taken into the analysis.

The scanned volume (vertex of the skull to mid-thigh) was divided into eight different compartments or regions (cervical, axillary, mediastinum, pulmonary, liver, other gastrointestinal organs, retroperitoneal space and bone).

In accordance with RECIST 1.1 criteria, measurements of the maximum lesion diameters on PET/CT and PET/MR images were obtained. In lymph nodes, the short axis was measured. PET-positive lesions that were morphologically invisible on CT or MRI could not be measured in that particular modality and were noted as “not measurable”. A four-point scale was used for assessment of lesion conspicuity: 1 (less than 25 % of lesion borders definable) = not detectable or poorly delimitable, 2 (25–50 % of borders definable) = moderately delimitable, 3 (50–75 % of borders definable) = well delimitable, 4 (more than 75 % of lesion borders definable) = excellently delimitable. For each lesion the corresponding anatomical structure was noted based on anatomical information of the spatially co-registered PET/CT and PET/MR image sections. Additionally, lesions were divided into three categories: “tumour mass”, “lymph nodes” and “lesions”. The first category was used if a mass was found within an organ (e.g. hypodense mass within the liver) exhibiting space-occupying characteristics like exceeding the organ surface/capsule or which exceeded organ specific boundaries within the organ itself (e.g. liver segments). The second category was used for lumps/tumours which were located in the lymphatic network of the evaluated compartment (e.g. retroperitoneal lymph nodes). The last category was used for all other lesions without mass characteristics, e.g. sclerotic or lytic bone lesions.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Differences between lesion size and conspicuity in PET/CT and PET/MRI were analysed by Wilcoxon signed ranks test. Analyses were performed for the above-mentioned three categories of lesions as well as for the above-mentioned eight body portions. A minimum of seven lesions per body portion/compartment was required for statistical analysis to achieve equal distributions for all categories analysed.

Results

The primary malignancy of 63 examined patients were malignant melanoma (n = 11; 17 %), lung cancer (n = 9; 14 %), breast cancer (n = 7; 11 %), Hodgkin’s lymphoma (n = 6; 9 %), cancer of unknown origin “cup” (n = 5; 8 %), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (n = 4; 6 %), gynaecology tumours (n = 4; 6 %), pleural mesothelioma (n = 3; 5 %), oesophageal cancer (n = 3; 5 %), colorectal cancer (n = 2; 3 %), stomach cancer (n = 2; 3 %) as well as seven individual cases of primary tumours located in the thymus, oral cavity, tongue, hypopharynx, larynx, thyroid gland and retroperitoneum (each 1.8 %). A total of 17 patients were excluded from further evaluation due to the absence of suspicious, tumorous lesions. Forty-six of the 63 patients examined with sequential PET/CT and MRI presented at least one lesion. A total of 126 lesions were evaluated (Table 1).

Overall lesion detection, conspicuity and lesion size

Wilcoxon signed ranks test yielded overall no statistically significant superiority of PET/CT over PET/MR or vice versa in terms of lesion conspicuity (p = 0.095; mean score PET/CT 2.93, mean score PET/MRI 2.75) (Table 2).

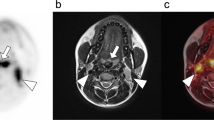

A total of 101 lesions were visible and measurable both on PET/CT and PET/MRI. Seventeen (16.8 %) lesions were visible only on PET/CT, six (6 %) were visible only on PET/MRI and two (1.9 %) were visible neither on CT nor on MRI (only PET-positive without a morphological correlate) (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). Seven of the 17 lesions visible only on PET/CT were lymph nodes (two perigastic, two cervical, two in the mediastinum and one single lymph node adjacent to the internal mammary artery), five were bone lesions, four were located in the lungs, and one lesion each in the thyroid and in the vagina were missed on PET/MRI. Three of the six lesions visible only on PET/MRI were mediastinal lymph nodes as well as one liver lesion, one thyroid lesion and one chest wall lesion. One PET-positive lesion in the breast and one in the colon were only visible on PET images without a morphological correlate on PET/CT and PET/MRI. Wilcoxon signed ranks test of the 101 visible lesions yielded no statistically relevant difference in terms of lesion size between CT and MRI (p = 0.251). The mean diameter was 20.21 mm (range 4–80 mm) for CT and 19.94 mm (range 4–82 mm) for MRI.

Comparison of PET/CT and PET/MRI of a patient with diffuse metastasis of malignant melanoma. Axial CT (a) and MRI (b) images show a large lymph node metastasis in the right groin (arrowhead) with corresponding 18F-FDG activity in axial PET/CT (c) and PET/MRI (d). In this patient, lesion conspicuity was rated as “excellently delimitable” (score 4) for both CT and MRI, no difference in image quality was observed. Note the non-avid seroma in the left groin (*)

Comparison of PET/CT and PET/MRI of a patient with lung cancer with intrapulmonary metastasis showing partial superiority of CT versus MRI. CT (a) and PET/CT (c) show two small, FDG-avid lung metastases (arrows), a large, left-sided, polylobular pleural metastatic tumour (*) and a partially/centrally necrotic metastatic tumour within the right lung (arrowhead). The right-sided necrotic lesion is only partly visible on the MRI (b) and PET/MRI (d)

Comparison of PET/CT and PET/MRI of a patient showing superiority of MRI versus CT. Axial MRI (b) and axial PET/MRI (d) images show a small FDG-avid liver metastasis in segment VII (arrowhead) adjacent to the liver vein. The lesion is only detectable in co-registered PET/CT images (c) but undetectable on unenhanced low-dose CT axial images (a)

Location (organ) based comparison of conspicuity and size

Regarding lesion conspicuity, Wilcoxon signed ranks test yielded a statistically significant superiority of PET/CT over PET/MRI in pulmonary lesions (p = 0.016). For all other organs/anatomical structures, no significant differences were found between PET/CT and PET/MRI concerning both lesion conspicuity and lesion size (Table 3).

Comparison of lesion conspicuity and size regarding lesion type

Thirty-seven out if the 126 PET-positive findings were characterised as “tumour mass”, 57 as “lymph node” and 17 as “lesion” (overall 111 PET-positive findings evaluated, not all PET-positive findings visible on PET/CT and/or PET/MRI, see above). The remaining findings (15 lesions, focal FDG-uptake without morphological correlate [see above], pulmonary nodules, abscess) did not fit in the here evaluated categories. Furthermore, the quantity of those lesions were below seven (see “Materials and methods”) and were therefore not further considered in this evaluation (Table 4).

Wilcoxon signed ranks test yielded a statistically significant superiority of PET/CT over PET/MRI for “lymph nodes” regarding lesion conspicuity (p = 0.033). No statistically significant difference was found in lesion conspicuity for “tumour mass” (p = 0.176) and for “lesion” (p = 0.700). Also no statistically significant difference was found in lesion diameter regarding all three lesion types (p = 0.124 for “tumour mass”; p = 0.213 for “lymph node”; p = 0.234 for “lesion”). One noticeable difference was found for bone lesions (see also Table 3). There was a higher mean score in PET/CT detected for bone lesions compared with PET/MRI. However, despite this demonstrative finding, no statistical significance could be established for this sub-category of “lesions”.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the diagnostic utility of a PET/MRI with only an axial T1-weighted fast gradient echo sequence using a body coil (which is the basic sequence needed for MR-based attenuation correction [MRAC]) compared with standard low-dose PET/CT. Generally, no significant differences were found concerning lesion size and conspicuity. However, there was an advantage of PET/CT over PET/MRI concerning detection of lung lesions and bone lesions, as well as in lymph node conspicuity. Overall, PET/MRI with just one sequence using a body coil does not match entirely the diagnostic accuracy of standard low-dose PET/CT and thus, might only serve as a back-up solution in very limited cases.

For our study, we used a tri-modality PET/CT-MRI system. In such a setting, the PET/CT or the MRI examination is done first and the other imaging modality follows directly after using the described dedicated shuttle solution [20]. This approach certainly is—like in PET/CT—a sequential approach but all acquired imaging modalities can be exactly co-registered based on the explained shuttle procedure. The goal of this study was to compare PET/CT and PET/MRI, and thus simultaneity of PET/MRI was not needed. Several controversies in MRI-based attenuation still have to be considered—e.g. segmentation of bone, air and soft tissue, as well as truncation artefacts [2, 21]. Therefore, since CT-based attenuation correction (CTAC) compared with MRI-based attenuation correction in simultaneous approaches is still considered the “gold standard”, it might be helpful to have such data still available as a back-up, especially in initial trial periods. During clinical routine, we still use the CTAC. The MRAC is evaluated for study purposes in our setting as well, however, those evaluations were beyond the scope of this manuscript. Furthermore, there are studies now indicating that, at least for routine diagnostic purposes (except for bone lesions), diagnostic differences are minor [22].

Comparison with current literature

Regarding the quantitative analysis of tracer uptake by SUV-based analysis, partly different SUVs have been observed for data acquired on the simultaneous PET/MRI compared with the PET/CT scanner for suspected lesions in other studies [10, 11, 16]. In general, the difference of mean SUVs between PET/CT and simultaneous PET/MRI can be explained by a delayed acquisition times after i.v. injection of the 18F-FDG, partly by tumour biology, by differences in the technological specifications and data-processing algorithms of the two hybrid scanners. Even initially missed lesions on PET/MRI have been reported; however, those were special cases in tumours which were not well suited for FDG-based imaging anyway [10]. In our described sequential set-up, we only have one measurement of SUV within the PET/CT examination, and thus no differences in SUV uptake and lesion-to-background contrast can occur. This way, constant PET volumes can be achieved for initial measurement and for therapy follow-up and no different tracer kinetics between the two examinations have to be considered.

Overall, lesion conspicuity was not statistically significant different in both PET/CT and PET/MRI. However, lung lesions and bone lesions were significantly better detectable and definable on PET/CT. This is in line with previous results from Eiber et al. [11], where PET/CT tended to be superior concerning delineation in lung lesions. The reasons for those results in PET/CT are certainly the higher speed and resolution of CT within the lungs. Lungs are known to be one of the most challenging organs in MRI. The reason why our results in PET/MRI were significantly lower might be the use of a body coil (the purpose of the study), which inherently has a lower image quality. In another study it was indicated that the CT component of the PET/CT actually detects more lesions as well [17]. However, no evaluation concerning differences in potentially treatable lung lesions was made. In the studies of Eiber et al. [11] and Drzezga et al. [10], no significant difference was found between water-only images and fat-only images as well as compared with in/opposed-phase images, which we can confirm in our study. In fact, reconstructed fat-weighted images were shown to be inferior compared to the other images. Initial results on PET/MRI in bronchial carcinoma showed that PET/MRI is feasible and provides in most patients similar lesion characterisation and tumour stage. However, the study included only a very small number of patients, only large tumours and PET/CT still showed better results concerning the TNM staging in almost one-third of the patients [16]. Overall there was no statistically significant difference when evaluating PET-positive lesions based on the lesion’s type in our study. However, we found significant differences when evaluation lymph nodes. This is in line with the previously mentioned studies where PET/CT tended to be superior in lymph node evaluation as well [11]. One reason might be that lymph nodes in the axilla and in areas with sufficient surrounding fatty tissue are easier to detect than lymph nodes close to vessels like in the retroperitoneal space or in the periportal region. However, it is slightly surprising that we found a statistically significant difference, although we used a higher matrix in PET/MRI (320 × 256 vs 79 × 192). Reasons for that finding might be a different distribution of lymph in the evaluated compartments and the somewhat low number of patients and lesions in our as well as in the aforementioned studies.

Other studies also reported that PET/CT tended to be superior to PET/MRI in the detection and conspicuity of bone lesions. Also in our study, there was a higher mean score found for PET/CT compared with PET/MRI for bone lesions, but those results did not yield any statistical difference. However, five bone lesions were detected on PET/CT but not on PET/MRI. It has already been shown in other studies that the detection and characterisation of bone lesions by PET/MRI is challenging, especially in therapy follow-up [15].

One limitation of our study is that histological results as the “gold standard” of reference were not available for all lesions evaluated. All patients underwent biopsy during the time course of their disease for establishment of the primary diagnosis, though. Another limitation is the different slice thickness of PET/MRI and PET/CT. But this inherent drawback was actually part of the study, since the body coil imaging was specifically evaluated. Basic body coil sequences are needed for the MRAC in PET/MRI. We investigated an inhomogeneous patient population, which can be considered as a drawback when drawing conclusions on specific tumour indications. However, in this way a general overview of such an evaluation can be provided.

Conclusions

Overall, when comparing standard PET/CT and basic PET/MRI with body coil acquisition—the basic sequence needed for the MRAC—PET/MRI does not entirely match the diagnostic accuracy of standard low-dose PET/CT. Thus, it might only serve as a back-up solution in very few patients. One task for the future of PET/MRI therefore might be the evaluation of how many MRI sequences and how much information from the MRI is needed (matrix, breath-holds, different weightings) to match up to a standard low-dose PET/CT, ideally within the same acquisition time.

References

Antoch G, Vogt FM, Freudenberg LS et al (2003) Whole-body dual-modality PET/CT and whole-body MRI for tumor staging in oncology. JAMA 290:3199–3206

Beyer T, Weigert M, Quick HH et al (2008) MR-based attenuation correction for torso-PET/MR imaging: pitfalls in mapping MR to CT data. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 35:1142–1146

Langer A (2010) A systematic review of PET and PET/CT in oncology: a way to personalize cancer treatment in a cost-effective manner? BMC Health Serv Res 10:283

Veit-Haibach P, Kuehle CA, Beyer T et al (2006) Diagnostic accuracy of colorectal cancer staging with whole-body PET/CT colonography. JAMA 296:2590–2600

Lonsdale MN, Beyer T (2010) Dual-modality PET/CT instrumentation-today and tomorrow. Eur J Radiol 73:452–460

Buchbender C, Heusner TA, Lauenstein TC et al (2012) Oncologic PET/MRI, part 2: bone tumors, soft-tissue tumors, melanoma, and lymphoma. J Nucl Med 53:1244–1252

Buchbender C, Heusner TA, Lauenstein TC et al (2012) Oncologic PET/MRI, part 1: tumors of the brain, head and neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis. J Nucl Med 53:928–938

Delso G, Furst S, Jakoby B et al (2011) Performance measurements of the Siemens mMR integrated whole-body PET/MR scanner. J Nucl Med 52:1914–1922

Delso G, Martinez-Moller A, Bundschuh RA et al (2010) Evaluation of the attenuation properties of MR equipment for its use in a whole-body PET/MR scanner. Phys Med Biol 55:4361–4374

Drzezga A, Souvatzoglou M, Eiber M et al (2012) First clinical experience with integrated whole-body PET/MR: comparison to PET/CT in patients with oncologic diagnoses. J Nucl Med 53:845–855

Eiber M, Martinez-Moller A, Souvatzoglou M et al (2011) Value of a Dixon-based MR/PET attenuation correction sequence for the localization and evaluation of PET-positive lesions. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 38:1691–1701

Ratib O, Beyer T (2011) Whole-body hybrid PET/MRI: ready for clinical use? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 38(6):992–995

Wehrl HF, Judenhofer MS, Wiehr S et al (2009) Pre-clinical PET/MR: technological advances and new perspectives in biomedical research. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 36(Suppl 1):S56–S68

Schwenzer NF, Schmidt H, Claussen CD (2012) Whole-body MR/PET: applications in abdominal imaging. Abdom Imaging 37:20–28

Samarin A, Burger C, Wollenweber SD et al (2012) PET/MR imaging of bone lesions–implications for PET quantification from imperfect attenuation correction. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 39:1154–1160

Schwenzer NF, Schraml C, Muller M et al (2012) Pulmonary lesion assessment: comparison of whole-body hybrid MR/PET and PET/CT imaging–pilot study. Radiology 264:551–558

Stolzmann P, Veit-Haibach P, Chuck N et al (2013) Detection rate, location, and size of pulmonary nodules in three-modality MR-PET/CT: comparison of low-dose CT and Dixon-based MR imaging. Invest Radiol 48:241-246

Mantlik F, Hofmann M, Werner MK et al (2011) The effect of patient positioning aids on PET quantification in PET/MR imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 38:920–929

Paulus DH, Braun H, Aklan B et al (2012) Simultaneous PET/MR imaging: MR-based attenuation correction of local radiofrequency surface coils. Med Phys 39:4306–4315

Samarin A, Kuhn F, Crook D et al (2011) Image registration accuracy of a sequential, trimodality PET/CT + MR imaging setup using dedicated patient transporter systems. Proceedings 97th Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, Chicago

Martinez-Moller A, Souvatzoglou M, Delso G et al (2009) Tissue classification as a potential approach for attenuation correction in whole-body PET/MRI: evaluation with PET/CT data. J Nucl Med 50:520–526

Wiesmüller M, Quick HH, Navalpakkam B et al (2013) Comparison of lesion detection and quantitation of tracer uptake between PET from a simultaneously acquiring whole-body PET/MR hybrid scanner and PET from PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 40(1):12–21

Disclosure

This work was financially supported by General Electric, Waukesha, IL, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Appenzeller, P., Mader, C., Huellner, M.W. et al. PET/CT versus body coil PET/MRI: how low can you go?. Insights Imaging 4, 481–490 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-013-0247-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-013-0247-7