Abstract

Biogas is a combination of methane, CO2, nitrogen, H2S and traces of few other gases. Almost any organic waste can be biologically transformed into biogas and other energy-rich organic compounds through the process of anaerobic digestion (AD) and thus helping in sustainable waste management. Although microbes are involved in each step of AD, knowledge about those microbial consortia is limited due to the lack of phylogenetic and metabolic data of predominantly unculturable microorganisms. However, culture-independent methods like PCR-based ribotyping has been successfully employed to get information about the microbial consortia involved in AD. Microbes identified have been found to belong mainly to the bacterial phyla of Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. Among the archaeal population, the majority have been found to be methanogens (mainly unculturable), the remaining being thermophilic microbes. Thus, the AD process as a whole could be controlled by regulating the microbial consortia involved in it. Optimization in the feedstock, pH, temperature and other physical parameters would be beneficial for the microbial growth and viability and thus helpful for biogas production in AD. Besides, the biogas production is also dependent upon the activity of several key genes, ion-specific transporters and enzymes, like genes coding for methyl-CoM reductase, formylmethanofuran transferase, formate dehydrogenase present in the microbes. Fishing for these high-efficiency genes will ultimately increase the biogas production and sustain the production plant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Worldwide energy consumption and demand are continuously growing up. But, most of the resources used like petroleum, natural gas, coal are not sustainable sources of energy. Numbers of countries in the world including India are currently passing through the critical phase of population explosion and the growing population demands more energy inputs. Therefore, the whole world is now concerned about sustainable renewable energy. As a burning example, the European Union policies have set a fixed target of supplying 20 % of the total European energy demands by the year 2020 from renewable energy systems (Holm-Nielsen et al. 2009).

Biogas technology seems promising to attain sustainable energy yields without damaging the environment only when it is produced through anaerobic digestion (AD) and recovered properly (Qiang et al. 2012; Chojnacka et al. 2015). It is composed of 50–75 % methane, 25–50 % carbon dioxide, 0–10 % nitrogen, 0–3 % hydrogen sulfide, 0–1 % hydrogen and traces of other gases. The term “anaerobic” suggests that the process occurs in the absence of free oxygen and produces CH4 through decomposition of waste in nature and reduces environmental pollution (Ward et al. 2008; Qiang et al. 2012).

The biogas process comprises of four stages (hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, methanogenesis) which are catalyzed by different and specialized microorganisms. Although AD processes have been carried out for several decades, knowledge about the microbial consortia involved in this process is limited due to lack of phylogenetic and metabolic data of these predominantly uncultivable microorganisms (Sträuber et al. 2012; Wirth et al. 2012; Chojnacka et al. 2015). Due to the wide variety of starting products, a complex array of microbial species are involved in the AD process, including some obligatory syntrophic organisms, which have greatly limited the value of traditional microbiological methods (O’Flahert et al. 2006; Wirth et al. 2012; Chojnacka et al. 2015). The microbial biogas production is solely an enzyme-driven process involving several ion-specific transporters but the functions of the majority of genes involved in various stages of AD are yet to be explored (Narihiro and SeKiguchi 2007; Demirel and Scherer 2008; Weiland 2010).

Though there are several reviews available on different aspects of biogas production there is a dearth of knowledge related to the different microbial community involved in different steps, the different role they play in each step, key genes involved and how to control these microbial communities to get optimal production of biogas (Wirth et al. 2012). In this review we have tried to focus on the core aspect of the biogas production which is the microbial community. We have also discussed on how to control this microbial community and their key genes involved in this process. Our review might also be helpful for the researcher to focus on fishing the important genes involved in this process to develop smarter biogas production plants.

Sustainable production of biogas through anaerobic digestion (AD)

The biogas is a sustainable source of energy because, (1) it is fully energy self-sufficient (itself produce the heat and electricity to run the process); (2) independent of any fossil fuel; (3) renewable, (4) carbon neutral and (5) reduces the emission of green house gases (GSGs) to the environment. The substrates from plants and animals only emit the carbon dioxide they have accumulated during their life cycle and which they would have emitted also without the energetic utilization. On the whole, electricity produced from biogas generates much less carbon dioxide than conventional energy and thus will be helpful in reducing green house gas emission (http://www.probiopol.de/2_Why_is_biogas_sustainable.41.0.html). Keeping this in mind, at least 25 % of all bioenergy in the future may originate from biogas (Holm-Nielsen et al. 2009). Waste management, manure production, health care and employment generation are the benefits of biogas system.

Microbes involved in biogas production

Culture-independent methods including polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based ribotyping, for the identification and characterization of microbial communities involved in biogas production, have met considerable success in recent times (Wirth et al. 2012; Chojnacka et al. 2015). Chouari et al. (2005) detected the constituents of more than 20 bacterial phyla from anaerobic (mostly methanogenic) waste and wastewater sludge using the culture-independent methods, of them, Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are most prominent (Chouari et al. 2005). Besides that, in a separate study, characterization of anaerobic microbial community related to biogas production has revealed the presence of Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actonobacteria, Bacteroides, Acidobacteria, Spirochetes, Chloroflexi (Chojnacka et al. 2015). Recently Ruminococcus flavefaciens, Eubacterium cellulosolvens, Clostridium cellulosolvens, Clostridium cellulovorans, Clostridium thermocellum, Bacteroides cellulosolvens and Acetivibrio cellulolyticus have also been reported as predominant fermentative bacteria in the cattle dung-fed digesters and actively involved in the AD process (Nagamani and Ramasamy 1999). In addition to these relatively known taxa, phylotypes belonging to a variety of uncultured phyla (known as ‘clone cluster’) have also been detected in sludge (Chouari et al. 2005).

Methanogens are mostly unculturable microorganisms (Wirth et al. 2012; Chojnacka et al. 2015). Earlier studies have reported that the majority of the Archaeal community identified from anaerobic digesters are very similar to already identified methanogens such as Methanosarcina barkeri, Methanosarcina frisius, Methanobacterium formicicum while the remaining are related to thermophilic microbes such as Crenarchaea or Thermoplasma sp. (Godon et al. 1997). With respect to the uncultured archaeal lineages, archaeal 16S rRNA gene clones affiliated with the candidate taxon ArcI (a clone cluster at the subphylum (or class) level within the archaeal phylum Euryarchaeota) has been retrieved in abundance from a mesophilic methanogenic digester decomposing sewage sludge. It has been proposed that ArcI could be an acetate consumer which might play a role in acetoclastic methanogenesis (Chouari et al. 2005). Another unique, uncultured archaeal taxon that is also often found in methanogenic sludge is subphylum C2 of the archaeal phylum Crenarchaeota. Moreover, 16 % of the archaeal rRNA gene clones analyzed from a mesophilic methanogenic digester has been found to belong to members of Crenarchaeota, particularly the subphylum C2 (Chouari et al. 2005).

Biochemical mechanisms of biogas production

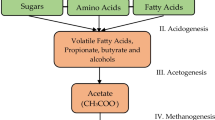

Biogas production by anaerobic digestion (AD) of wastes is a combinational activity of diverse microbial populations. According to Heeg et al. (2014), the AD chain is initiated by bacteria that are responsible for the hydrolysis of high molecular weight organic substances. Subsequently, the mono- and oligomers produced are further degraded to volatile fatty acids (VFAs) (acidogens) and then to acetic acid, as well as CO2 and H2 (acetogens). The final step (methanogenesis) is accomplished by acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic Archaea, which convert acetic acid or CO2/H2 into methane (Fig. 1).

Hydrolysis

The very first step of AD is very important as large organic molecules are not readily absorbable. In this step, several microbes secrete different enzymes, which cleave the complex macromolecules into simpler forms. Organisms that are active in a biogas process during the hydrolysis of polysaccharides include various bacterial groups such as Bacteriodes, Clostridium, and Acetivibrio (Cirne et al. 2007; Doi 2008; Heeg et al. 2014). Some of these organisms have several different enzymes combined into cellulosomes (large, stable, multi-enzyme complexes specialized in the adhesion to and degradation of cellulose that reside with protuberances visible on the cell surface) that are situated on the organism’s cell wall (Liang et al. 2014).

Acidogenesis

The diversity of the microbial consortium involved in AD reaches its peak during this stage. Most of the microbes involved in hydrolysis step are also involved in fermentation. Along with them, microbes belonging to the genera like Enterobacterium, Acetobacterium and Eubacterium also carry out the process of fermentation (Schnurer and Jarvis 2010). Through various fermentation reactions, the products from hydrolysis are converted mainly into various organic acids (acetic, propionic acid, butyric acid, succinic acid, lactic acid, etc.), alcohols, ammonia (from amino acids), carbon dioxide and hydrogen. Exactly which compounds are formed depends on the substrate and environmental process conditions, as well as on the microbes present (Schnurer and Jarvis 2010).

Acetogenesis

In this step, the fermented products are oxidized into simpler forms. According to Heeg et al. (2014), this step in the AD process requires close co-operation between the microbes that carry out oxidation and the methanogens that are active in the next stage (which actually produce methane). Substrates for acetogenesis consist of various fatty acids, alcohols, some amino acids and aromatics (Heeg et al. 2014). In addition to hydrogen gas, these compounds primarily form acetate and carbon dioxide (Heeg et al. 2014). Syntrophomonas, Syntrophus, Clostridium, and Syntrobacter are examples of genera in which there are numerous organisms that can perform acetogenesis in syntrophy with an organism that uses hydrogen gas (McInerney et al. 2008).

Methanogenesis: the key step for methane production

Methanogenesis (final step inside AD) is the methane production pathway which methanogens follow to obtain energy (Fig. 2). This process involves the fermentation of various organic compounds with methane gas as the major end product along with carbon dioxide, hydrogen and traces of other gases. Methanogenesis has six major pathways, each converting a different substrate into methane gas. The six major substrates used are carbon dioxide, formic acid, acetic acid, methanol, methylamine, and dimethyl sulfate (Slonczewski and Foster 2014). The most common pathway converts carbon dioxide into methane through the reduction of H2/CO2 (Slonczewski and Foster 2014) (Fig. 2). The other five pathways may be converged into two according to various methanogen specific-cofactors. The pathway which leads to the methane production solely depends on the methanogenic consortia and the availability of the suitable substrates that favors the digestion process. Methane is, therefore, a by-product of this anaerobic decomposition process that aims to break down organic acids and produce energy for the microbes present in the environment (Wang et al. 2011). Therefore, the main three pathways (Fig. 2) are:

Biochemical pathways to produce CH4 from different starting material during AD. a Methylotrophic methanogenesis. b Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis. c Acetotrophic methanogenesis. MF, methanofuran; CHO-MF, formylmethanofuran; Fd 2−red , reduced ferrodoxin; Fdox, oxidized ferredoxin; FDM (W/Mo-FMD), (tungsten/molybdenum-dependent) formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase; H4MPT, tetrahydromethanopterin; FTR, Formylmethanofuran: tetrahydromethanopterin formyltransferase; CHO–H4SPT, formylmethanofuran; MCH, N 5,N 10-methenyl tetrahydromethanopterin cyclohydrolases; CH≡H4SPT+, methenyl tetrahydromethanopterin; F420H2, reduced cofactor F420; MTD, coenzyme F420-dependent N 5,N 10-methylene tetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenase; CH2=H4SPT, methylene tetrahydromethanopterin; MER, N 5,N 10-methylene tetrahydromethanopterin reductase; CH3–H4SPT, methyl tetrahydromethanopterin; CoM–SH, coenzyme M; MTR, N 5-methyl tetrahydromethanopterin: Coenzyme M methyltransferase; CH3–S–CoM, methyl coenzyme M; CoB–SH, coenzyme B; MCR, methyl coenzyme M reductase; CoM–S–S–CoB, coenzyme M-HTP heterodisulfide

-

1.

Methylotrophic methanogenesis, i.e., production of methane by decarboxylation of methyl alcohols/methyl amines/methyl sulfides, etc. (Fig. 2a),

-

2.

hydrogenophilic or hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, i.e., production of methane by the reduction of H2/CO2 (Fig. 2b); and,

-

3.

acetoclastic or acetotrophic methanogenesis, i.e., production of methane by acetate decarboxylation (Fig. 2c).

It has been reported that acetoclastic methanogenesis is the major pathway of methane production in anaerobic digestion as 70 % of the total methane generated during AD of domestic sewage is via this pathway (Lettinga 1995; Merlino et al. 2013).

Although the role of methanogens and methane production have been extensively studied, the exact process and pathway of methanogenesis is not well described in most literature (Weiland 2010; Wirth et al. 2012; Chojnacka et al. 2015). It is often simply described as the conversion of organic acids or carbon dioxide into methane (Toprak 1995; Wu et al. 2009). The true process of methanogenesis is much more complex and requires specific substrates and cofactors to occur. The two most common methanogenesis substrates are carbon dioxide and acetate. In the carbon dioxide pathway (hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis), CO2 is converted into methane and water via the passing of carbon down a series of cofactors. Carbon dioxide is fixed using hydrogen into methanofuran. The carbon is then passed down three cofactors, Tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT), Coenzyme F420 or 8-hydroxy-5-deazaflavin (F420), and 2-Mercaptoethanesulfonic Acid or coenzyme M (HS-CoM), until the carbon reaches coenzyme B (HS-CoB), which serves as the terminal electron acceptor (Slonczewski and Foster 2014). This process depends on the concentration of hydrogen ions as well as the sodium potential to donate electrons from CO2 and drive the ATP synthase that ultimately produces energy for the methanogens (Slonczewski and Foster 2014). Due to this, methanogens, unlike many other microbes, require sodium ions for growth. Methanogenesis from acetate (acetoclastic methanogenesis) requires the coupling of H2 concentration and a sodium potential to occur and uses the cofactors HS-CoM (coenzyme M) and HS-CoB (coenzyme B) to produce methane (Slonczewski and Foster 2014). Unlike hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, which produces water as a waste product, acetate methanogenesis produces a molecule called coenzyme M-HTP heterodisulfide (CoM–S–S–CoB), which is a converged form of the two carbons initially entered into the system (Slonczewski and Foster 2014).

Factors affecting microbial community in AD for biogas production

The anaerobic digestion of organic material is a complex process, involving a number of different degradation steps performed by different members of the microbial consortia. Thus, a number of factors affect the microbial growth which in turn affects the process of anaerobic digestion and hence, the biogas yields (Mathew et al. 2014). As the hydrolytic/acidogenic bacteria and methanogenic Archaea differ widely in their preferred ambience, such as pH optima and nutrient requirements, the success of any process optimization effort crucially depends on the degree to which the growth, metabolism of all microorganisms involved is supported (Heeg et al. 2014). The effects of few such factors have been discussed below:

Temperature

Anaerobic digestion is applied under three different temperature ranges, i.e., the mesophilic (25–40 °C), the thermophilic (45–60 °C) and the psychrophilic (<20 °C) (Khalid et al. 2011; Mathew et al. 2014). The structures of the active microbial communities at the two temperature optima are quite different. A change from mesophilic to thermophilic temperature (or vice versa) can result in a sharp decrease in biogas production until the necessary populations have increased in number (Chae et al. 2008).

pH

pH plays a major part in anaerobic biodegradation by influencing the activity of the hydrolytic enzymes (Mathew et al. 2014). It has been reported that methanogenesis in an anaerobic digester occurs efficiently at pH 6.5–8.2, while hydrolysis and acidogenesis occurs at pH 5.5 and 6.5, respectively (Lee et al. 2009).

C/N ratio

The C/N ratio in the organic material plays a crucial role in anaerobic digestion (Mathew et al. 2014). The unbalanced nutrients are regarded as an important factor limiting anaerobic digestion of organic wastes. It has been reported that the optimal C/N ratio for anaerobic degradation of organic waste is 20–35 (Lee et al. 2009; Mathew et al. 2014). However, in reality, C/N ratios of the feedstocks are often much lower or higher than this (Zhang et al. 2008). Hence, co-digestion of feedstock is employed to improve the C/N ratio.

COD

Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) content describes the amount of oxygen needed to completely oxidize the waste under aerobic conditions, and is determined experimentally by measuring the amount of a chemical oxidizing agent needed to fully oxidize a sample of the waste. It is used as a measure of the oxygen equivalent of the organic matter content of a sample that is susceptible to oxidation by a strong chemical oxidant. Oxygen is not consumed in anaerobic digestion, and so, no reduction of COD can occur. In this situation, COD is removed by converting organic compounds to methane (CH4), a significant amount of CO2, H2 and negligible amounts of other gases like H2S (Manariotis et al. 2010; Mathew et al. 2014). So the methane potential of a waste (by microorganisms) is related to the concentration of organics (COD) in it and in the efficiency of the system.

Nutritional requirements

The nutrient requirement is a major concern for the stable operation of methane fermentation processes (Mathew et al. 2014). The growth of methanogens is dependent on many ions such as sodium, nickel, cobalt, iron, zinc, magnesium, calcium and potassium cations and molybdate or tungstate and phosphate anions. Except sodium, which is required for coupling methanogenesis with ADP phosphorylation, all the other ions are required for the synthesis of enzymes, prosthetic groups, and coenzymes (Hattori et al. 2009; Kaster et al. 2011). It has also been reported that the optimal requirements for Fe, Co, and Ni were identified as 200, 6.0, and 5.7 mg/kg COD removed for the methane fermentation of food waste (Qiang et al. 2012). Methanogenic cell concentrations in excess of 1.32, 1.13, 0.12, 4.8, and 30 g l−1 have been found to be limited by Fe at a concentration of 5 mg l−1, Zn at 1 mg l−1, Cu at 0.1 mg l−1, Ni at 1.2 mg l−1, and Co at 4.8 mg l−1, respectively (Zhang et al. 2008).

Crucial role of important ion channels in the growth of methanogenic microorganisms

Methanogenesis is one of the most metal enriched enzymatic pathways in biology. Depending on the pathway, exact metal requirements may differ, but the general trends always remain the same. Iron (Fe) is the most abundantly required metal, followed by nickel (Ni) and cobalt (Co), and trace amounts of molybdenum (and/or tungsten) and zinc (Zn). Fe remains as Fe–S clusters used for transport of electrons (Glass and Orphan 2012). Ni is either bound to Fe–S clusters or in the center of a porphyrin unique to methanogens, cofactor F430. Cobalt is present in cobamides involved in methyl group transfer; whereas Zn occurs as a single structural atom in several enzymes. Molybdenum (Mo) or tungsten (W) is attached to a ‘pterin’ cofactor to form “molybdopterin” or “tungstopterin”, respectively, and involved in catalyzing two electron redox reactions. Other alkali metals and metalloids, such as sodium (Na) and selenium (Se), are also essential for methanogenesis (David and Alm 2010; Dupont et al. 2006, 2010; Glass and Orphan 2012). All these ions, all of which are required for the synthesis of enzymes, prosthetic groups, and coenzymes, must be taken up from the growth medium.

Sodium channel

Sodium ions (Na+) are required for coupling methanogenesis with ADP phosphorylation. It is transported by four membrane-bound enzyme complexes, N 5Methyl-H4MPT:CoM methyltransferase (MTR), energy-converting [Ni–Fe]-hydrogenase complexes EHA and EHB, A1A0 ATP synthase complex AHA, and a sodium ion/proton antiporter NHA (Lang et al. 2015; Kaster et al. 2011).

The methyltransferase enzyme is a four membrane-associated integral membrane-bound complex which requires sodium ions for activity and, in addition to methyl transfer, functions to generate a sodium ion gradient across the membrane. The ATP synthase shows a conserved Na+-binding motif, and utilized four sodium ions for the phosphorylation of one ADP (Kaster et al. 2011). Reduction of ferredoxin with H2 via Eha or Ehb was driven by the sodium ion-motive force with a Na+ to e − stoichiometry of 1; however, this has not yet been established (Lang et al. 2015). The sodium/proton antiporter is most likely there for pH homeostasis (Kaster et al. 2011).

Nickel channel

Nickel ions (Ni2+) are required for the synthesis of the [Ni–Fe]-hydrogenase complexes (EhaA-T, EhbA-Q, FrhABG, and MvhADG). EHA and EHB is responsible for catalyzing the reduction of ferredoxin with H2 driven by proton-motive force; whereas, FRH catalyzes the reversible reduction of coenzyme F420 with H2 (Zhang et al. 2009; Kaster et al. 2011). They are also required for the synthesis of the two methyl-CoM reductases: McrABG and MrtABG and the carbon monoxide-acetyl-CoA synthase/decarbonylase complex involved in autotrophic CO2 fixation. Although the Ni2+ transporter is yet to be identified, one of the two Co2+ transporters predicted in two Methanobacter species has been proposed to be a Ni2+ transporter (Kaster et al. 2011).

Cobalt channel

Cobalt ions (Co2+) are required for the synthesis of cobalamin in the MTR enzyme complex (containing two cobamide cofactors and eight Fe atoms) and of coenzyme B12 in the adenosyl cobalamin-dependent ribonucleotide reductase. They are most probably taken up by the transporter CBIMNOQ (Zhang et al. 2009; Kaster et al. 2011; Glass and Orphan 2012).

Iron channel

The iron requirement for methanogenesis is vast; almost every metalloenzyme involved in the methanogenesis pathway contains multiple Fe2S2, Fe3S4, or Fe4S4 clusters (Rao et al. 2011). Ferrous ions (Fe2+) are required for the synthesis of iron–sulfur clusters in the [Ni–Fe] hydrogenases, formylmethanofuran dehydrogenases (W/Mo-FMD), heterodisulfide reductase (HDR), ferredoxins (Fd), and [Fe] hydrogenase (HMD) (Kaster et al. 2011). The Fe2+ ions are transported by the FeoAB transporter encoded by feoAB gene (Rao et al. 2011).

Zinc channel

Zinc ions (Zn2+) are required for the synthesis of the subunit B of HDR enzyme (involved in CO2 reduction with H2 to methane) and RNA polymerases. The Zn2+ ions are translocated by the high-efficiency ZnuABC/ZupT transporters in Methanothermobacter marburgensis and M. thermautotrophicus which are regulated by the nickel-responsive transcriptional regulator NikR homolog (Wang et al. 2009; Kaster et al. 2011). However, NikR from E. coli can also bind zinc ions, but without having any conformational change in the transporter (Leitch et al. 2007; Kaster et al. 2011).

Magnesium channel

The synthetase and kinase enzymes generally use complexes of ATP and ADP with Mg2+ as substrates and products. Mg2+ is predicted to be taken up by the MgtE system (Rao et al. 2011).

Calcium channel

Calcium ions (Ca2+) are required for the synthesis of Mch enzyme and a membrane-bound Ca2+ ATPase (Qiang et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2008). It is reported that methane formation in cell suspensions of microorganisms is stimulated by the gradient of Ca2+ ions which is driven by the membrane-associated Ca2+ ATPase (Kaster et al. 2011). Though the presence of Ni2+ and Co2+ in the microbial growth media has been reported to antagonize the Ca2+ transport, available evidence indicates that if a Ca2+ uptake system is present, it must be a high-affinity uptake system (Kaster et al. 2011).

Potassium channel

Potassium ions are not directly involved in methanogenesis from CO2 and H2O, but most of the methanogenic enzymes function optimally only at high concentration of K+ ions. Most methanogenic bacteria have developed K+ transporters and channels, which have enabled them to withstand different environmental stresses. Basically, K+ channels are ion-selective pores, composed of two or four subunits, which conduct selective uptake of potassium ions along the electrochemical gradient. The potassium ions are most probably taken up by the low-affinity TrkAH system (Zhang et al. 2009; Kaster et al. 2011).

Molybdate/tungstate channel

Molybdate ions (MoO4 2−) are required for the synthesis of the Mo-formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase (MO-FMD), formate dehydrogenase, and nitrogenase and are most likely taken up by the ABC transporter ModA1B1C1 (Zhang et al. 2008). Tungstate ions (WO4 2−) are required for the synthesis of the W-FMD and are most likely taken up by the ABC transporter ModA2B2C2 (Zhang et al. 2008; Kaster et al. 2011).

Phosphate channel

In methane production from CO2 and H2, phosphate ions are required in ATP formation via the A1A0 ATP synthase and for the synthesis of the coenzyme H4MPT, coenzyme B, and the FeGP-cofactor, which contain covalently bound phosphate. The phosphate ions are probably taken up by a PstABCS/PhoU system (Aguena and Spira 2009; Kaster et al. 2011).

Key genes involved in biogas production

Microbial biogas (methane) production is a genetically regulated process (Fig. 2). The key genes involved in this process are discussed below:

Formylmethanofuran transferase (FTR) catalyzes the transfer of a formyl group from formylmethanofuran (MFR) to tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT) (Fig. 2). The FTR-encoding gene from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum has been cloned, sequenced, and functionally expressed in E. coli. Formate dehydrogenase (FDH) may sometimes account for 2–3 % of the total soluble proteins in methanogenic cultures (Darcy et al. 1995). The two genes encoding the a± and a2 subunits of FDH have been cloned and sequenced from Methanobacterium formicicum. In addition, the genes encoding F420-reducing hydrogenase, ferredoxin, and ATPase have also been cloned (Darcy et al. 1995; White and Ferry 1992).

Methyl-CoM reductase (MCR) constitutes approximately 10 % of the total protein in methanogenic cultures (Klein et al. 1988). The importance and abundance of MCR inevitably focused initial attention on elucidating its structure and the mechanisms directing its synthesis and regulation. MCR-encoding genes have been cloned and sequenced from Methanococcus vanielli, Methanococcus voltae, M. barkeri, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum and Methanothermus fervidus (Cram et al. 1987; Lehmacher and Klenk 1994).

A considerable amount of information relevant to natural DNA transformations of prokaryotic bacteria has been reported, and the natural competence of methanogens has been elucidated. Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum was transformed by DNA from fluorouracil-resistant strains, resulting in the production of drug-resistant strains. In Methanococcus voltae, auxotrophic mutants requiring histidine or purine were reverted with wild-type DNA, although the genetic transformation frequencies were very low (Micheletti et al. 1991). However, Gernhardt et al. (1990) recently made a breakthrough with integration of a vector into Methanococcus voltae. Integration vector transformation techniques have been well exploited in yeasts, but not in methanogens. The hisA gene cloned from the methanogen was used as an integration site in homologous recombination. In methanococcus, a puromycin-resistant gene from Streptomyces alboniger was clearly shown to be expressed and stably maintained only under specific pressure conditions (Sandbeck and Leigh 1991). Further characterization of the integration mode revealed that the integration vector was tandemly repeated in chromosomal genes of Methanococcus maripaludis under intensive antibiotic pressure (Sandbeck and Leigh 1991). Furthermore, genomic DNA from the recipient methanogen could directly transform E. coli to ampicillin resistance, indicating that integrated plasmid vectors can be used as recoverable shuttle vectors between methanogens and E. coli (Sandbeck and Leigh 1991).

Developments in bioreactor technology for sustainable production of biogas

A bioreactor may refer to any manufactured or engineered device or system that supports a biologically active environment (Wu et al. 2009). The process of biogas production takes place in anaerobic conditions and in different temperature diapasons. There are psychrophilic (temperature diapason 10–25 °C), mesophilic (25–40 °C) and thermophilic (50–55 °C) regimes of bioconversion. Biogas production in a thermophilic regime is much higher than for the mesophilic and psychrophilic regimes. Modern thermophilic bioreactors can produce 2–6 m3 per m3 of installation, which amounts to 5–15 kg of waste on a dry mass base (or 50–150 kg of wet mass). For mesophilic biogas installations, these values are 0.2–0.4 m3 per m3 of installation and 0.5–1 kg on a dry mass base (or 5–10 kg of wet mass). Biogas reactors, working in a thermophilic regime, can be introduced in agricultural farms where the number of livestock exceeds 5. Biogas produced on such farms can be used not only for cooking and heating water, but for dairy production as well (Wu et al. 2009). Process imbalances and overloading are often accompanied by an accumulation of propionic acid (Marchaim and Krause 1993; Wang et al. 2006). It is generally accepted that the propionic acid concentration should be kept below 1.5 g l−1 for proper process operation (Ma et al. 2007), and the ratio of propionic/acetic acid was suggested to be a sufficient indicator of a digester failure (Marchaim and Krause 1993).

For biogas production, research and developmental efforts have been directed at retaining a high density of useful microorganisms, to achieve rapid and effective treatment, with the objective of improving the conventional system. To this end, considerable technological developments in microbial floe formation and in microbial adhesion onto carrier materials which retain cells in the reactor have been made. For the former purpose, the upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) (Lettinga et al. 1980) has proven useful, while for the latter, the upflow anaerobic filter process (UAFP) (Young and McCarty 1969; Rajathi 2013) and anaerobic fluidized-bed reactor (AFBR) (Jeris 1983; Buffieare et al. 2000) have been developed (Fig. 3). In all of these newly developed processes, however, acidogenesis may occur more frequently than methanogenesis, leading to the accumulation of inhibitory products such as volatile fatty acids. Two-phase anaerobic digestion processes have been developed to resolve this problem (Bowker 1983; Sharma et al. 2012) (Fig. 3).

Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB)

Successful construction of a UASB process capable of affording self-granulation (flocculation) of anaerobic microbes was first reported by Lettinga et al. (1980). In this type of bioreactor, water containing organic waste entering from the bottom of the reactor passes through a sludge bed and sludge blanket where organic materials are anaerobically decomposed. Gas produced is then separated by a gas–liquid separator and the clarified liquid is discharged over a weir, while the granular sludge naturally settles at the bottom (Krzysztof and Frac 2012) (Fig. 3a). Bench- and pilot plant-scale experiments indicate that it is possible to operate this system at a COD loading of 40 kg/m3/day at HRTs of 4–24 h (Krzysztof and Frac 2012). Full-scale UASB reactors are now operational in Europe, the US and Japan, with more than 100 recently constructed plants in Japan.

Significant parameters in the UASB operation are floe diameter, microbial density, and the structure of the gas–solid separator which effectively retains the microbial granules within the reactor. The following criteria should be observed to achieve successful UASB operation: (a) selection of a suitable waste water capable of granule self-formation; (b) operation of the reactor without mechanical agitation; (c) start up at a relatively low COD load; (d) use of waste water containing Ca2+ and Ba2+ and (e) avoidance of bulking caused by filamentous microbial growth. Granule formation in a UASB system is influenced by the growth of rod-type Methanothrix spp. which produces spherical granules (Krzysztof and Frac 2012).

Upflow anaerobic filter process (UAFP)

UAFP systems were initially developed by Young and McCarty (1969) using rocks and plastics for microbial fixation. These UAFP systems were applied to biogas production from domestic sewage and industrial waste waters containing relatively low levels of organic materials. This type of bioreactor contains a “medium”, i.e., a microbial support (Fig. 3b). Granulated microorganisms exist not only in the spaces within the medium, but are also attached to its surface; hence, a high-density microbial population is retained within the reactor, creating a hybridization of microbial floe and adhesion. To avoid short-circuiting flow through the packed column, a distributor is fitted at the bottom to provide a homogeneous upflow of waste water. At the top, treated waste water and the biogas produced are separated by a free board. Data on full-scale UAFP systems show that alcohol distillery waste water can be treated at an HRT of 7.8 days with 74 % COD removal. Application of this UAFP to domestic sewage treatment using Raschig rings (2.5 cm) as microbial supports, resulted in BOD removal of 50–60 % and suspended solids (SS) removal of 70–80 %, at an HRT ranging from 5 to 33 h (Young and McCarty 1969).

Selection of a medium in which microbial adhesion is greatly influenced both by SS, and the chemical composition of the waste water, is extremely critical in UAFP systems (Mumme et al. 2010). Entrapment of methane-producing microorganisms between semi-permeable synthetic membranes in a multi-layer membrane bioreactor (MMBR) was studied and compared to the digestion capacity of a free-cell digester, using a hydraulic retention time of 1 day and organic loading rates (OLR) of 3.08, 6.16, and 8.16 g COD/L day (Youngsukkasem et al. 2013). The effects of physical medium characteristics, such as size and shape, on COD removal have been investigated using modular corrugated blocks (porosity > 95 %), pall rings, and perforated spheres. At a COD load of 2 kg/m/day, modular corrugated blocks exhibited superior behavior, removing 88 % of COD. A comparison of COD removal for cross- and tubular-flow systems reveals that COD removal is 20–30 % greater in cross-flow systems. In addition to plastic media, baked clay and a melted slug have also proven useful in laboratory experiments on methanogenesis from formate, acetate, and methanol. Pumice was used as a microbial supporter for methanogenesis from methanol-rich waste water of the evaporate condensate from a pulp mill (COD load: 12 kg/m3/day, COD removal: 96 %) (Youngsukkasem et al. 2013).

Anaerobic fluidized-bed reactor (AFBR)

In this type of systems, the medium to which the microbes adhere is fluidized within the reactor, resulting in conversion of organic materials to CH4 and CO2 (Krzysztof and Frac 2012) (Fig. 3c). Anaerobic microbes grow on the surface of the medium, expanding the apparent volume of the medium; hence this reactor is also designated an “expanded bed reactor”. Use of artificial sewage in an AFBR, resulted in COD removal exceeding 80 % at 20 °C, and at a COD load of 2–4 kg/m3/day this system was tolerant of shock loading for step changes of temperature from 13 to 35 °C and from 35 to 13 °C. In the case of COD shock loading from 1.3 to 24 kg/m3/day, a steady state is established after 6 days (Jeris 1983; Buffieare et al. 2000).

The AFBR thus seems to be capable of performing at relatively low temperatures with both low and high COD waste waters, without significant shock loading effects. Engineering improvements which can potentially minimize the mechanical power required for fluidization include reduction of the expanded volume, selection of a low-density medium of high specific area; and avoidance of fragility. Media such as sand, quartzite, alumina, anthracite, granular activated carbon, or cristobalite with a particle size of approximately 0.5 mm are usually employed (Buffieare et al. 2000).

Two-phase methane fermentation processes

Novel bioreactors for biogas fermentation such as the UASB, UAFP, and AFBR experience inherent problems when operated at high COD loads, due to the fact that the overall growth rate of acidogenic bacteria proceeds faster (tenfold) than that of methanogenic bacteria. When this occurs, inhibitory products such as volatile fatty acids and H2 accumulate in the reactor, slowing down the entire process. To overcome this, two-phase processes consisting of acidogenic and methanogenic fermentations have been investigated (Bowker 1983; Ke and Shi 2005; Xie et al. 2012; Sharma et al. 2012; Heeg et al. 2014; Berni et al. 2014) (Fig. 3d). In addition, since SS in waste water greatly influences the performance of the UASB or UAFP, an acidogenic fermentation first phase in combination with a UASB or UAFP second phase is useful in reducing the SS which enter the second phase.

In one full-scale two-phase system 70–97 % COD removal and biogas production of 3–13 kg/m2 day with a methane content of 65–80 % was obtained when operated at COD loads of 20–60 kg/m3/day for acidogenic fermentation (1st phase) and 6–30 kg/m3/day for methanogenic fermentation (2nd phase). In another example, a two-phase system consisting of a complete stirred reactor for the first phase and a UASB for the second phase was constructed. When this system was applied in the treatment of alcohol distillery waste (COD = 10,000 mg/l) at HRTs of 16–72 h in the first phase, and 14 h in the second phase, 84 % COD removal and 92 % BOD removal were accomplished. A two-phase system consisting of a UAFP for the first phase and a horizontal AFP for the second phase has also been proposed, with which it should be possible to treat sewage waste water (COD 800–2600 mg/l) at HRTs of 2–5.5 h with a high methane content (~90 %) (Berni et al. 2014).

Conclusion

Worldwide energy consumption and demand are growing up since past 50 years. With the growth of population, demand for energy is also increasing leading to an uneven supply and distribution of resources. Therefore, the requirement of sustainable and eco-friendly energy in India to satisfy the energy demand is inevitable. Along with the source of sustainable green energy, biogas production is an alternative way to produce clean energy through solid waste management. As it is produced by the action of several microbes upon the waste products, knowledge about the eco-physiology of the microbes will help in understanding their particular roles. Bearing in mind that the higher biogas production rate of the thermophilic system must have been accompanied by intensified intermediate production, it is noteworthy that the concentration of VFA within the UAFP effluent was equally low at both temperatures. Consequently, the acetogenesis and methanogenesis steps must also have been more active and the intermediates from hydrolysis and acidogenesis were instantly converted to methane within the thermophilic UAFP reactor. For biogas production methanogenesis is often the rate-limiting step. However, when plant biomasses are used as substrate, hydrolysis is the rate-limiting step because of higher content of lignocellulosic materials. Thus, to enhance the overall production rate in such processes, it is necessary to understand the primary degradation steps, i.e., hydrolysis and acidogenesis, for the control and optimization of the whole process. As all the microbes involved in AD are not culturable, attempts could be made to design ideal media and optimize the growth conditions for the non-culturable microbes with the aid of metagenomic improvements, so that extensive research could be done in cost-effective and easier ways. The eco-physiological effect of a microbe in the consortium can also be understood properly only if it can be cultured in vitro. Several microbes detected in the AD system have been found to be methane oxidizers and sulphate reducers, which are hindrances to the yield of biogas. Thus, studies on inhibiting the growth of such microbes would be beneficial for the biogas yield. Besides, the performance of AD in terms of biogas production is dependent upon the activity of several ion-specific transporters and enzyme systems. Detailed information on structure and biosynthesis of all the enzymes, biogenesis of the prosthetic groups involved in such enzyme systems is also not readily available. Hence, further studies could be designed to explore these steps. Fishing for these high-efficiency genes that control these enzyme systems will ultimately increase the production of biogas and sustain the production plant.

References

Aguena M, Spira B (2009) Transcriptional processing of the pst operon of Escherichia coli. Curr Microbiol 58:264–267

Berni M, Dorileo I, Nathia G, Forster-Carneiro T, Lachos D, Santos BGM (2014) Anaerobic digestion and biogas production: combine effluent treatment with energy generation in UASB reactor as biorefinery annex. Int J Chem Eng. doi:10.1155/2014/543529

Bowker RPG (1983) New wastewater treatment for industrial applications. Environ Prog 2:235–242

Buffieare P, Bergeon JP, Moletta R (2000) The inverse turbulent bed: a novel bioreactor for anaerobic treatment. Water Res 34:673–677

Chae KJ, Jang A, Yim SK, Kim IS (2008) The effects of digestion temperature and temperature shock on the biogas yields from the mesophilic anaerobic digestion of swine manure. Bioresour Technol 99:1–6

Chojnacka A, Szczęsny P, Błaszczyk MK, Zielenkiewicz U, Detman A, Salamon A, Sikora A (2015) Noteworthy facts about a methane-producing microbial community processing acidic effluent from sugar beet molasses fermentation. PLoS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128008

Chouari R, Le PD, Daegelen P, Ginestet P, Weissenbach J, Sghir A (2005) Novel predominant archaeal and bacterial groups revealed by molecular analysis of an anaerobic sludge digester. Environ Microbiol 7:1104–1115

Cirne DG, Lehtomaki A, Bjornsson L, Blackhall LL (2007) Hydrolysis and microbial community analysis in two-stage anaerobic digestion of energy crops. J Appl Microbiol 103:516–527

Cram DS, Sherf BA, Libby RT, Mattalianos RJ, Ramachandran KL, Reeve JN (1987) Biochemistry Structure and expression of the genes, mcrBDCGA, which encode the subunits of component C of methyl coenzyme M reductase in Methanococcus vannielii. Proc Natl Acad Sci 84:3992–3996

Darcy TJ, Sandman K, Reeve JN (1995) Methanobacterium formicicum, a mesophilic methanogen, contains three HFo histones. Bacteriol 177:858–860

David LA, Alm EJ (2010) Rapid evolutionary innovation during an Archaean genetic expansion. Nature 469:93–96

Demirel B, Scherer P (2008) The roles of acetotrophic and hydrogenotrophic methanogens during anaerobic conversion of biomass to methane: a review. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 7:173–190

Doi RH (2008) Cellulases of mesophilic microorganisms: cellulosome and noncellulosome producers. Ann NY Acad Sci 1125:267–279

Dupont CL, Yang S, Palenik B, Bourne PE (2006) Modern proteomes contain putative imprints of ancient shifts in trace metal geochemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103:17822–17827

Dupont CL, Butcher A, Ruben RE, Bourne PE, Caetano-Anolles G (2010) History of biological metal utilization inferred through phylogenomic analysis of protein structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107:10567–10572

Gernhardt P, Possot O, Foglino M, Sibold L, Klein A (1990) Construction of an integration vector for use in the Archaebacterium Methanococcus voltae and expression of a eubacterial resistance gene. Mol Gen Genet 221:273–279

Glass JB, Orphan VJ (2012) Trace metal requirements for microbial enzymes involved in the production and consumption of methane and nitrous oxide. Front Microbiol. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00061

Godon JJ, Zumstein E, Dabert P, Habouzit F, Moletta R (1997) Molecular microbial diversity of an anaerobic digestor as determined by small-subunit rDNA sequence analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:2802–2813

Hattori M, Iwase N, Furuya N, Tanaka Y, Tsukazaki T, Ishitani R, Maguire ME, Ito K, Maturana A, Nureki O (2009) Mg2+-dependent gating of bacterial MgtE channel underlies Mg2+ homeostasis. EMBO 28:3602–3612

Heeg K, Pohl M, Mumme J, Klocke M, Nettmann E (2014) Microbial communities involved in biogas production from wheat straw as the sole substrate within a two-phase solid-state anaerobic digestion. Syst Appl Microbiol 37:590–600

Holm-Nielsen JB, Al Seadi T, Oleskowicz-Popiel P (2009) The future of anaerobic digestion and biogas utilization. Bioresour Technol 100:5478–5484

Jeris JS (1983) Industrial wastewater treatment using anaerobic fluidized bed reactors. Water Sci Technol 15:169–176

Kaster AK, Goenrich M, Seedorf H, Liesegang H, Wollherr A, Gottschalk G, Thauer RK (2011) More than 200 genes required for methane formation from H2 and CO2 and energy conservation are present in Methanothermobacter marburgensis and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus. Archaea. doi:10.1155/2011/973848

Ke S, Shi Z (2005) Applications of two-phase anaerobic degradation in industrial wastewater treatment. Environ Pollut 23:65–80

Khalid A, Arshad M, Anjum M, Mahmood T, Dawson L (2011) The anaerobic digestion of solid organic waste. Waste Manage 31:1737–1744

Klein A, Allmansberger R, Bokranz M, Knaub S, Müller B, Muth E (1988) Comparative analysis of genes encoding methyl coenzyme M reductase in methanogenic bacteria. Mol Gen Genet 213:409–420

Krzysztof Z, Frac M (2012) Methane fermentation process as anaerobic digestion of biomass: transformations, stages and microorganisms. Afr J Biotechnol 11:4127–4439

Lang K, Schuldes J, Klingl A, Poehlein A, Daniel R, Brune A (2015) New mode of energy metabolism in the seventh order of methanogens as revealed by comparative genome analysis of “Candidatus Methanoplasma termitum”. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:1338–1352

Lee DH, Behera SK, Kim J, Park HS (2009) Methane production potential of leachate generated from Korean food waste recycling facilities: a lab scale study. Waste Manag 29:876–882

Lehmacher A, Klenk HP (1994) Characterization and phylogeny of mcrII, a gene cluster encoding an isoenzyme of methyl coenzyme M reductase from hyperthermophilic Methanothermus fervidus. Mol Gen Genet 243:198–206

Leitch S, Bradley MJ, Rowe JL, Chivers PT, Maroney MJ (2007) Nickel-specific response in the transcriptional regulator, Escherichia coli NikR. J Am Chem Soc 129:5085–5095

Lettinga G (1995) Anaerobic digestion and wastewater treatment systems. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 67:3–28

Lettinga G, Van Velsen AFM, Hobma SW, de Zeeuw WJ, Klapwijk A (1980) Use of upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor concept for biological wastewater treatment especially for anaerobic treatment. Biotechnol Bioeng 22:699–734

Liang Y-L, Zhang Z, Wu M, Wu Y, Feng J-X (2014) Isolation, screening, and identification of cellulolytic bacteria from natural reserves in the subtropical region of China and optimization of cellulase production by Paenibacillus terrae ME27-1. BioMed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2014/512497

Ma J, Van Wambeke M, Carballa M, Verstraete W (2007) Improvement of the anaerobic treatment of potato processing wastewater in a UASB reactor by codigestion with glycerol. Biotechnol Lett 30:861–867

Manariotis ID, Grigoropoulos SG, Hung YT (2010) Anaerobic treatment of low-strength wastewater by a biofilm reactor. In: Wang LK, Tay JH, Tay ST, Hung YT (eds) Handbook of environmental engineering, vol 11. Humana Press, New York. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-031-1

Marchaim U, Krause C (1993) Propionic to acetic-acid ratios in overloaded anaerobic-digestion. Bioresour Technol 43:195–203

Mathew AK, Bhui I, Banerjee SN, Goswami R, Shome A, Chakraborty AK, Balachandran S, Chaudhury S (2014) Biogas production from locally available aquatic weeds of Santiniketan through anaerobic digestion. Clean Technol Environ Policy. doi:10.1007/s10098-014-0877-6

McInerney MJ, Struchtemeyer CG, Sieber J, Mouttaki H, Stams AJ, Schink B, Rohlin L, Gunsalus RP (2008) Physiology, ecology, phylogeny, and genomics of microorganisms capable of syntrophic metabolism. Ann NY Acad Sci 1125:58–72

Merlino G, Rizzi A, Schievano A, Tenca A, Scaglia B, Oberti R, Adani F, Daffonchio D (2013) Microbial community structure and dynamics in two-stage vs single-stage thermophilic anaerobic digestion of mixed swine slurry and market bio-waste. Water Res 47:1983–1995

Micheletti PA, Sment KA, Konisky J (1991) Isolation of a coenzyme M-axotrophic mutant and transformation by electroporation in Methanococcus voltae. Bacteriol 173:3414–3418

Mumme J, Linke B, Toelle R (2010) Novel upflow anaerobic solid-state (UASS) reactor. Bioresour Technol 101:592–599

Nagamani B, Ramasamy K (1999) Biogas production technology: an Indian perspective. Curr Sci 77:44–55

Narihiro T, Sekiguchi Y (2007) Microbial communities in anaerobic digestion processes for waste and wastewater treatment: a microbiological update. Curr Opin Biotechnol 18:273–278

O'Flahert V, Collins G, Mahony T (2006) The microbiology and biochemistry of anaerobic bioreactors with relevance to domestic sewage treatment. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 5:39–55

Qiang H, Langa D-L, Li Y-Y (2012) High-solid mesophilic methane fermentation of food waste with an emphasis on iron, cobalt, and nickel requirements. Bioresour Technol 103:21–27

Rajathi RP (2013) Efficiency of HUASB reactor for treatment of different types of wastewater—a review. Int J Eng Res Technol 2:465–471

Rao AG, Prakash SS, Joseph J, Reddy AR, Sarma PN (2011) Multi stage high rate biomethanation of poultry litter with self mixed anaerobic digester. Bioresour Technol 102:729–735

Sandbeck KA, Leigh JA (1991) Recovery of an integration shuttle vector from tandem repeats in Methanococcus maripaludis. Appl Environ Microbiol 57:2762–2763

Schnurer A, Jarvis A (2010) Microbiological handbook for biogas plants. Swedish Waste Management U2009:03, Swedish Gas Centre Report 207, pp 1–74

Sharma PK, Khan NA, Ayub S (2012) Modelling of COD reduction in a UASB reactor. Glob J Eng Appl Sci 2:178–182

Slonczewski JL, Foster JW (2014) Microbiology: an evolving science, 3rd edn. W.W. Norton and Company, New York

Sträuber H, Schröder M, Kleinsteuber S (2012) Metabolic and microbial community dynamics during the hydrolytic and acidogenic fermentation in a leach-bed process. Energy Sustain Soc. doi:10.1186/2192-0567-2-13

Toprak H (1995) Temperature and organic loading dependency of methane and carbon dioxide emission rates of a full-scale anaerobic waste stabilization pond. Water Res 29:1111–1119

Wang CH, Lin PJ, Chang JS (2006) Fermentative conversion of sucrose and pineapple waste into hydrogen gas in phosphate-buffered culture seeded with municipal sewage sludge. Process Biochem 41:1353–1358

Wang SC, Dias AV, Zamble DB (2009) The “metallospecific” response of proteins: a perspective based on the Escherichia coli transcriptional regulator NikR. Dalton Trans 14:2459–2466

Wang Q, Thompson E, Parsons R, Rogers G, Dunn D (2011) Economic feasibility of converting cow manure to electricity: a case study of the CVPS cow power program in Vermont. Dairy Sci 94:4937–4949

Ward AJ, Hobbs PJ, Holliman PJ, Jones DL (2008) Optimization of the anaerobic digestion of agricultural resources. Bioresour Technol 99:7928–7940

Weiland P (2010) Biogas production: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 85:849–860

White WB, Ferry JG (1992) Identification of formate dehydrogenase-specific mRNA species and nucleotide sequence of the fdhC gene of Methanobacterium formicicum. Bacteriol 174:4997–5004

Wirth R, Kovacs E, Maroti G, Bagi Z, Rakhely G, Kovacs KL (2012) Characterization of a biogas-producing microbial community by short-read next generation DNA sequencing. Biotechnol Biofuels. doi:10.1186/1754-6834-5-41

Wu B, Bibeau EL, Gebremedhin KG (2009) Three-dimensional numerical simulation model of biogas production for anaerobic digesters. Can Biosyst Eng 51:8.1–8.7

Xie S, Wu G, Lawlor PG, Frost JP, Zhan X (2012) Methane production from anaerobic co-digestion of the separated solid fraction of pig manure with dried grass silage. Bioresour Technol 104:289–297

Young JC, Mccarty PL (1969) Anaerobic filter for waste treatment. Water Pollut Control Fed 41:160–173

Youngsukkasem S, Akinbomi J, Rakshit SK, Taherzadeh MJ (2013) Biogas production by encased bacteria in synthetic membranes: protective effects in toxic media and high loading rates. Environ Technol 34:2077–2084

Zhang P, Zeng G, Zhang G, Li Y, Zhang B, Fan M (2008) Anaerobic co-digestion of biosolids and organic fraction of municipal solid waste by sequencing batch process. Fuel Process Technol 89:485–489

Zhang Y, Rodionov DA, Gelfand MS, Gladyshev VN (2009) Comparative genomic analyses of nickel, cobalt and vitamin B12 utilization. BMC Genom. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-78

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks are due to DST (DST/SEED/INDO-UK/002/2011/VBU), Government of India for financial support and research fellowships to RG, AS, SNB, AKC, and AKM. Thanks to Dr. S. Balachandran, Department of Environmental Studies, Visva-Bharati, India for helping in manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Additional information

Pritam Chattopadhyay and Arunima Shome have contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Goswami, R., Chattopadhyay, P., Shome, A. et al. An overview of physico-chemical mechanisms of biogas production by microbial communities: a step towards sustainable waste management. 3 Biotech 6, 72 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0395-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0395-9