Abstract

In the present study, 20 sandalwood (Santalum album L.) genotypes were characterized using RAPD, ISSR and SSR markers. Twenty-five RAPD and twenty-one ISSR primers that generated clear and reproducible banding patterns amplified 225 and 208 bands, respectively, among 20 sandalwood genotypes. Out of 225, 181 (83.13 %) RAPD bands were polymorphic while out of 208, 156 (75.77 %) ISSR bands were polymorphic. The average polymorphism information content (PIC) for RAPD and ISSR was 0.84 and 0.86, respectively. A good correlation (0.96) was observed between the matrices produced by RAPD and ISSR primers. Though, there was high similarity among genotypes (0.79 for RAPD and 0.70 for ISSR), the observed genetic diversity was found good enough for the characterization of sandalwood genotypes. Cross-species transferability SSR markers developed in S. austrocaledonicum and S. insulare were found to be monomorphic. The results of the present investigation would provide valid guidelines for collection, conservation and characterization of sandalwood genetic resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sandalwood (Santalum album L; 2n = 20) is one of the important tropical trees which is commercially known for its fragrance (Shashidhara et al. 2003). It is member of family Santalaceae and being as perfumery material it is commonly known as chandan. It is a small- to medium-sized hemiparasitic tree, distributed rather widely in India. Sandalwood is mostly confined to the South Indian states, especially Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, and is indigenous to Peninsular India (Srinivasan et al. 1992).

S. album or Indian sandalwood is of great commercial value due to its fragrant heartwood which yields unique oil preferred for perfumeries, cosmetics, medicines and also in incense sticks industries. Sandalwood oil has antipyretic, antiseptic, antiscabietic, and diuretic properties and is also effective in the treatment of bronchitis, cystitis, dysuria, and diseases of the urinary tract. The seeds are used as diuretic, hypotensive, antitumorigenic, antiviral agents, and for treating a number of skin diseases (Kirthikar and Basu 1987; Desai and Shankaranarayana 1990).

Globally, with high economic value of sandalwood and its oil, sandalwood wealth in forests are declining due to overharvesting and illegal poaching in natural habitats (Naseer et al. 2012). This alarming genetic erosion condition indicates that there is need to conserve this commercially important tree species. To protect the species, efforts have been made to establish ex situ conservation gardens for sandalwood in India (Rao et al. 2011). But the conservation efforts and planning suffer from lack of information on the level and structure of natural genetic variability of sandalwood populations (Rao 2004). Hence, to examine the existing genetic variability, there is urgent need for systematic variability study in sandalwood.

Initially, isozymes served as reliable markers for genetic analysis in sandalwood (Rao et al. 1998, 2007a; Angadi et al. 2003) but this biochemical based marker was relatively low in abundance hence revealed low polymorphism. Moreover, like phenotypic markers, isozymes may also be affected by environmental conditions depending on the type of tissue used for the analysis. On the contrary, PCR-based molecular/DNA markers like RAPD, ISSR and SSR are dispersed throughout the genomes, more polymorphic due to its abundance, environmentally independent and are easier to analyse. A number of studies have been conducted to understand the genetic diversity of sandal using random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) (Shashidhara et al. 2003; Suma and Balasundaran 2004; Azeez et al. 2009), simple sequence repeat markers (SSRs) (Mohammed et al. 2012) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (Byrne et al. 2003). Due to unavailability of native SSR, most of the diversity analysis studies in sandalwood were conducted independently with RAPD, ISSR and cross-species transferable SSR markers. However, none has tried to assess the comparative accuracy and reproducibility of different markers for the characterization of sandalwood for better depiction of genetic diversity of sandalwood. The present investigation was initiated with the objective to assess and compare the efficiency of RAPD, ISSR and SSR markers in assessment of genetic diversity prevalent in Indian sandalwood collection.

Materials and methods

Plant material and DNA extraction

Leaf samples of a total of 20 sandalwood (Table 1) trees were collected from different places of Gujarat (Fig. 1). DNA from leaves was isolated using CTAB technique (Doyle and Doyle 1990), purified, and quantified using Nanodrop (Thermo scientific, USA). Finally, DNA was diluted to 20 ng/μl with TE buffer for PCR amplification.

PCR parameters and gel analysis

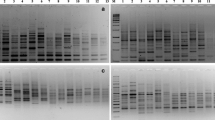

A total of 57 primers (25 RAPD, 21 ISSR and 11 SSR) were used for PCR amplification. PCR amplification was carried out in Biometra thermalcyclers (Germany). For PCR amplification, 25 µl reaction volume containing 2.5 µl template DNA (50 ng), 1× Dream Taq PCR buffer with MgCl2 (Fermentas, USA), 0.4 µl (5 U/µl) Taq polymerase (Fermentas, USA), 0.5 µl (2.5 mM each) dNTPs (Fermentas, USA) and 1 µl (10 pmol/µL) primer (MWG biotech, Germany) was used. RAPD amplification was performed according to Shashidhara et al. (2003) using decamer primers (Operon technologies Inc, USA; SIGMA-D, USA). RAPD-PCR was performed at an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 38 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 38 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1.2 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The optimal annealing temperature for ISSR primers was found to vary according to the base composition of the primers. Therefore, ISSR-PCR was performed at an initial denaturation temperature of 94 °C for 5 min, 38 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 48–58 °C (depending on primer sequence) for 40 s and 72 °C for 1 min and a final extension of 72 °C for 10 min.

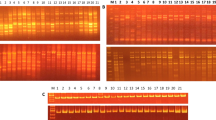

In the present study, SSRs developed in S. austrocaledonicum (Bottin et al. 2005) and S. Insulare (Emeline et al. 2006) were exploited for diversity analysis in sandalwood. PCRs for SSR were carried out in a final of volume of 10 μl containing 20 ng template DNA, 1× PCR buffer, 0.2 mMdNTPs, 0.5 pM of each primer, and 0.1 U Taq polymerase (Dream Taq, Thermo Scientific, USA). PCR was carried out with following programming: 94 °C for 3 min (denaturation), followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 48–58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min.

Amplified products were electrophoresed in 1.5 % agarose for (RAPD and ISSR) and 2.5 % for SSR in 1× TBE buffer. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and documented using gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California). Each experiment was repeated two times with each primer and those primers which gave reproducible fingerprints (DNA bands) were only considered for further experimentation and data analysis.

Data analysis

For each genotype, each fragment/band that was amplified using primers was treated as unit character. Unequivocally reproducible bands were scored and entered into a binary character matrix (1 for presence and 0 for absence). The pairwise genetic similarity coefficient (GS) was calculated using Jaccard coefficient (Jaccard 1908) by the SIMQUAL program of NTSYS-pc software version 2.02 (Rohlf 1998). A dendrogram was constructed based on the matrix of distance using Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic averages (UPGMA).

To compare the efficiency of primers, polymorphic information content (PIC), as a marker discrimination power, was computed using the formula PIC = 1−∑P 2 i , where pi is the frequency of the ith allele at a given locus (Anderson et al. 1993). The PIC values are commonly used in genetics as a measure of polymorphism for a marker locus using linkage analysis. Correlation between the matrices obtained by marker types was estimated by means of Mantel test using MxComp module of NTSYSpc.

Results and discussion

Forest and trees are renewable resources and contribute substantially to economic development. Overexploitation of forests for commercial purposes and other developmental activities have resulted in serious threat to tree species including sandal wood. In four decades, sandalwood production slumped from 4000 to 400 tonne a year (Times of India 2012). Overexploitation and poaching pushed this commercial forest tree in vulnerable category of the IUCN Red List (Kumar et al. 2012). Prohibition on export caused smuggling of sandalwood. The government of India’s Godowns have 15,000 tonnes of seized stock of sandalwood worth 5000 crore Indian rupees value in 2013 (Mahammadh 2014). Sandalwood grows naturally in the forest and since there is no systematic cultivation, this tree is at the face of increased exploitation. Therefore, genetic diversity analysis is essential for both the long-term stability and short-term productivity of trees as diversity provides clues to the factors that direct the variation, inbreeding and gene flow. The efforts to conserve decreasing genetic resources suffer from lack of precise information on genetic diversity (Naseer et al. 2012).

RAPD-based diversity analysis

The data collected from 25 RAPD primers produced 225 total bands, of which 181 (83.13 %) were polymorphic (Table 2). Dani et al. (2011) obtained only 65.99 % polymorphism, which indicated that presently studied genotypes are more diverse. High polymorphic bands have been observed in many woody tree species with similar life cycles (Lacerda et al. 2001; Shrestha et al. 2002). However, the polymorphism level was low than stated by Suma and Balasundaran (2004) where 91.67 % of the RAPD loci were polymorphic. Previously, it has been reported that genetic diversity was higher among states of South India. The molecular size of the amplified PCR products ranged from 109 (OPP 14) to 2251 bp (OPF 05). Average numbers of loci per primer were nine and average numbers of polymorphic loci obtained per primer were found to be 7.12. The PIC values ranged from 0.70 (OPP 04) to 0.92 (OPA 02) with an average of 0.84. Primer OPA 02 generated maximum 15 loci.

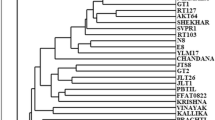

Jaccard’s similarity coefficients based on RAPD markers among the all pairwise combinations of genotypes ranged from 0.42 (GSA10/GSA15) to 0.87 (GSA1/GSA2) with a mean of 0.79 (Table 3). The results are in agreement with Suma and Balasundaran (2004) where relative magnitude of genetic similarity within populations was 0.77. The UPGMA clustering algorithm based on RAPD data grouped 20 genotypes into five clusters at cutoff value of 0.71 (Fig. 2). The RAPD-based dendrogram showed that cluster I consisted of maximum 16 genotypes of sandalwood and genotypes GSA 1 and GSA 2 (from Anand region) and GSA12 and GSA13 (from Vadodara region) clustered together. However, clusters II, III, IV and V each comprised of only one genotype. The results obtained in the present investigation are almost in agreement with the results of Azeez et al. (2009) and Dani et al. (2011).

High variation in sandalwood is usually related with geographic occurrence, habitat fragmentation and vegetative reproduction (Dani et al. 2011). The genetic diversity detected in the present study could be due to distance factor as the genotypes studied were widely distributed in different regions. Moreover, the heterozygous and heterogeneous structure of sandalwood population driven by its out breeding behaviour might be reason for high degree of polymorphism variability (Shashidhara et al. 2003).

ISSR profile and diversity analysis

The data collected from ISSR markers with 21 arbitrary primers produced 208 total loci, of which 156 (75.77 %) were polymorphic (Table 4). Average numbers of loci per primer were found to be 9.90 and average numbers of polymorphic loci obtained per primer were found to be 7.42. The molecular size of the amplified PCR products ranged from 66 (ISD 21) to 1980 bp (UBC 815). The PIC values ranged from 0.79 (ISD 7 and UBC 890) to 0.91 (ISD 4, UBC 811, UBC 818, and UBC 834) with an average of 0.86. The values of observed PIC were in congruence with PIC (0.76–0.95) in 30 Jatropha accessions (Tanya et al. 2011). Marker UBC 858 generated maximum 14 loci.

The similarity coefficient value ranged from 0.57 (GSA 1 and GSA19) to 0.81 (GSA 11 and GSA 15) indicating that the distribution of variation was diverse (Table 3). The average coefficient similarity for all the genotypes was found to be 0.70 (Fig. 3). Arif et al. (2009) obtained 0.56 to 0.93 similarity coefficient value in tree Dualbergia sissoo. The ISSR-based UPGMA clustering algorithm grouped genotypes in nine clusters at a cutoff value of 0.70. Maximum eight genotypes were grouped into cluster II. Cluster III harboured two genotypes (GSA 16 and GSA 17) at 100 % similarity coefficient. The results obtained in the present study portray slightly less polymorphism level compared to Basha and Sujatha (2007) but higher than Tanya et al. (2011), Gautan et al. (2013) in Jatropha.

SSR analysis

During cross-species amplification in sandalwood, out of 16 SSR of S. austrocaledonicum and S. insulare, 11 primers gave successful amplification thus revealing transferability of SSR markers (Table 5). The cross species transferability results indicated that the sequences flanking the microsatellite regions in Santalum are highly conserved across species. The success rate is in agreement with Naseer et al. (2012) where out of 16, 12 primers amplified SSR loci in 20 genotypes of S. album. Further, examination of the polymorphism for the microsatellite primer pairs within sandalwood showed lack of genetic variation indicating the highly conserved nature of these loci in genus Santalum. Naseer et al. (2012) also found single and monomorphic locus for six SSRs. Similar results have been also reported in tree species by many researchers. While assessing cross-species amplification of SSRs from eucalyptus to Casuarina equisetifolia, Yasodha et al. (2005) found monomorphism for all the locus-specific products. Similarly, no genetic variation was observed by Rao et al. (2007b) during cross-species amplification of coconut SSRs in rattans. Recently, efforts were made to elucidate information from monomorphic markers (Holla et al. 2014) through nucleotide variations in monomorphic amplicons of SSR. Thus, monomorphic markers which are usually eliminated from the further study could be the ones that are associated with the trait of interest. In addition, the monomorphic primers need to be tested in a larger set of isolates.

Correlation between RAPD and ISSR markers and pooled clustering analysis

Similarity was observed to be high among genotypes on the basis of RAPD (0.79) and ISSRs (0.70) with average genetic variation up to 21 and 30 %, respectively. This was also reflected by high correlation (r = 0.96) between RAPD and ISSR analysis. High correlation values between two marker systems have been reported earlier in many plants species (Abdelhamid et al. 2014). High correlation might be due to the fact that both molecular types are dominant markers and that each marker system samples a very small fraction of the genome that was arbitrarily amplified (Table 6).

Due to high correlation, UPGMA cluster analysis was also carried out using pooled RAPD and ISSR data. Jaccard’s similarity coefficient in pooled analysis ranged from 0.52 to 0.81 with a mean of 0.67. During pooled RAPD and ISSR analysis, Desai et al. (2015) also observed similar similarity coefficient range in bamboo. The UPGMA clustering algorithm based on pooled data grouped 20 genotypes into three clusters at cutoff value of 0.66 (Fig. 4). Clustering pattern derived using both the markers were found more or less similar when compared to the pooled RAPD and ISSR dendrogram. Desai et al. (2015) have also observed similar results in bamboo.

Conclusion

The present study using RAPD and ISSR presented some valuable information about sandalwood diversity. Cross-species transferability of SSR indicated the conservation of primer binding site across the genera. However, compared to less reproducible marker, there is necessity to develop suitable and highly reproducible genomic resources viz. SSR or SNP in S. album for better genome coverage and for unravelling its variability to understand species relationships and for germplasm conservation.

References

Abdelhamid S, Cong-Linh LÊ, Conedera M, Küpfer P (2014) The assessment of genetic diversity of Castanea species by RAPD, AFLP, ISSR, and SSR markers. Turk J Bot 38:835–850

Anderson JA, Churchill GA, Autrique JE, Tanksley SD, Sorrells ME (1993) Optimizing parental selection for genetic linkage maps. Genome 36:181–186

Angadi VG, Jain SH, Shankaranarayana KH (2003) Genetic diversity between sandal populations of different provenances in India. Sandalwood Res Newslett 17:4–5

Arif M, Zaidi NW, Singh YP, Haq QMR, Singh US (2009) A comparative analysis of ISSR and RAPD markers for study of genetic diversity in shisham (Dalbergiasissoo). Plant Mol Biol Rep 27:488–495

Azeez SA, Nelson R, Prasadbabu A, Rao MS (2009) Genetic diversity of Santalum album using random amplified polymorphic DNAs. Afr J Biotech 8(13):2943–2947

Basha SD, Sujatha M (2007) Inter and intra-population variability of Jatrophacurcas (L.) characterized by RAPD and ISSR markers and development of population-specific SCAR markers. Euphytica 156:375–386

Bottin L, Vaillant A, Sire P, Cardi C, Bouvet JM (2005) Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci in Santalumaustro caledonicum, Santalaceae. Mol Ecol Notes 5:800–802

Byrne M, MacDonald B, Broadhurst L, Brand JE (2003) Regional genetic differentiation in western Australian sandalwood (Santalumspicatum) as revealed by nuclear RFLP analysis. Theor Appl Genet 107:1208–1214

Dani KGS, Ravikumar P, Pravinkumar R, Kush A (2011) Genetic variation within and among small isolated populations of Santalum album. Biol Plant 55:323–326

Desai VB, Shankaranarayana KH (1990) On the utilization aspects of sandal seed oil. Res Ind 35:232–233

Desai P, Gajera B, Mankad M, Shah S, Patel A, Patil G, Subhash N, Kumar N (2015) Comparative assessment of genetic diversity among Indian bamboo genotypes using RAPD and ISSR markers. Mol Biol Rep 42(8):1265–1273

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL (1990) Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12:13–14

Emeline L, Alexandre V, Francoist BJ, Marc BJ (2006) Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci in Santaluminsulare, Santalaceae. Mol Ecol Notes 6(3):653–655

Gautan MSG, Patel F, Punwar BS, Patel M, Singh AS, Fougat RS (2013) Comparison of RAPD, ISSR, and DAMD markers for genetic diversity assessment between accessions of Jatrophacurcas L. and its related species. J Agri Sci Tech 15:1007–1022

Holla KMS, Khan JA, Sowjanya MS, Shashidhar HE (2014) Monomorphic molecular markers are as informative as polymorphic molecular markers. Indian J Genet 74(4):596–601

Jaccard P (1908) Nouvellesrecherchessur la distribution florale. Bull Soc Vaud Sci Nat 44:223–270

Kirthikar KR, Basu BD (1987) Indian medicinal plants. International Book Distributors, Dehradun

Kumar ANA, Joshi G, MohanRam HY (2012) Sandalwood: history, uses, present status and the future. Curr Sci 103(12):1408–1416

Lacerda DR, Acedo MDP, LemnosFilho JP, Lovato MB (2001) Genetic diversity and structure of natural populations of Plathymenia reticulate (Mimosoideae), a tropical tree from Brazilian cerrado. Mol Ecol 9:1843–1853

Mahammadh VR (2014) Smuggling of red sandal wood in India: a review study. EPRA Int J Econ Bus Rev 2(10):55–63

Naseer M, Shashank M, Kumar P, Ansari SA (2012) Genotyping of Santalum album L. accessions through cross-species transferability of SSR markers of Santalum austrocaledonicum and Santalum insulare. Sandalwood Res Newslett 27:1–5

Rao MN (2004) Mapping genetic diversity of Sandal (Santalum album L.) genetic resources in peninsular India using biochemical and molecular markers: lessons for in situ conservation. PhD thesis, Forest Research Institute (FRI), ICFRE

Rao MN, Ganeshaiah KN, Uma Shaanker R (2007a) Assessing threats and mapping sandal (Santalum album L.) resources in peninsular India: identification of genetic hot-spot for in situ conservation. Conserv Genet 8:925–935

Rao MN, Ramesha BT, Ravikanth G, Ganeshaiah KN, Uma SR (2007b) Cross-species amplification of coconut microsatellite markers in rattans. Silvae Genet 56(6):282–286

Rao MN, Soneji JR, Sudarshana P (2011) Santalum. In: Kole C (ed) Wild crop relatives: genomic and breeding resources forest trees. Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin, pp 131–144

Rao MN, Anuradha M, Deepali SBS, Uma SR, Ganeshaiah KN (1998) Sandal genetic resources: how safe are they? In: Interaction meeting on biodiversity and conservation in B.R. Hills. Institute of Wood Science and Technology, Bangalore

Rohlf FJ (1998) NTSys-pc. Numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system, version 2.02.Exter Software, Setauket

Shashidhara G, Hema MV, Koshy B, Farooqi AA (2003) Assessment of genetic diversity and identification of core collection in sandalwood germplasm using RAPDs. J Hort Sci Biotech 78:528–536

Shrestha MK, Golan-Goldhrish A, Ward D (2002) Population genetic structure and conservation of isolated populations of Acacia raddiana in Negev desert. Biol Conserv 108:119–127

Srinivasan VV, Shivaramakrishnana VR, Rangaswamy CR, Anathapadmanabha HS, Shankaranarayan KH (1992) Sandal. Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education, Dehradun

Suma TB, Balasundaran M (2004) Genetic diversity of eight Santalum album provenances of India based on RAPD analysis. Indian J Genet Plant Breed 64:167–168

Tanya P, Taeprayoon P, Hadkam Y, Srinives P (2011) Genetic diversity among Jatropha and Jatropha-related species based on ISSR markers. Plant Mol Biol Rep 29(1):252–264

Times of India (2012) Demise of sandalwood. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/Demise-of-sandalwood/articleshow/12078008.cms

Yasodha MG, Ramasam S, Krish G (2005) Cross-species amplification of eucalyptus SSR markers in Casuarinaceae. J Acta Bot Croat 64:115–120

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Department of Agricultural Biotechnology, AAU, Anand for providing the necessary facilities to successfully complete this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, D.M., Fougat, R.S., Sakure, A.A. et al. Detection of genetic variation in sandalwood using various DNA markers. 3 Biotech 6, 55 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0391-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0391-0