Abstract

Laboratory-based nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements from cores and the distribution of transversal T2 relaxations are usually employed for modelling petrophysical properties of reservoir rocks, due to their sensitivity to pore-size distribution, which invariably controls capillary pressures and permeabilities. Several methods have been proposed to derive synthetic drainage capillary pressures directly from NMR data. However, most approaches lack geologic calibration of the dataset and empirical correction factors are usually introduced in the scaling factor to improve the capillary pressure prediction at low wetting phase saturation. Volokitin et al. (A practical approach to obtain primary drainage capillary pressure curves from NMR core and log data, SCA-9924, 2001) proposed an approach for NMR T2 capillary pressure modelling based on a relationship between the NMR T2 and pore-throat distribution embedded within a single universal proportionality parameter termed kappa, κ; where: they concluded that the universal scaling factor, κ = 3 psi Hg s seems to work for all clastic reservoirs. In this present work, analysis aimed at validating the existence of the proposed relationship between measured capillary pressures and inverse NMR T2 distribution after Volokitin et al. indicate a nonlinear relationship. Pore throat distribution and accessible pore volumes analysis using a full-bore core mercury injection capillary pressure data from the Niger Delta Deep Water canyon reservoir demonstrates a single kappa factor is insufficient in characterizing pore throat distribution for reservoir with complex lithologies. Measured capillary pressures were compared with NMR derived ones for calibration with emphasis on various genetic reservoir units (lithofacies association). It suffices then to conclude that there exists no direct linear relationship between the NMR T2 distributions and pore throat distributions. In addition, a constant scaling factor for kappa is insufficient in modelling subsurface capillary pressures/pore throat distribution from NMR T2 data. An improved approach for NMR capillary pressure modelling can be obtained through local calibration, possibly allowing the kappa, κ scaling factor to vary as a function of rock types (pore size/grain sorting) and influence of clay diagenesis within the clastic system. The method has been applied successfully to a number of core samples from the clastic turbidites with a wide range of permeabilities. The NMR derived and primary drainage mercury injection capillary pressure curves show a very good agreement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An alternative approach to derive primary drainage capillary pressures from core NMR measurements and their associated distribution of transversal (cross-sectional) relaxation T2 times from well data was developed by Volokitin et al. (2001). The approach relies on an underlying assumption that a relationship exists between pore-body radius (as represented by the NMR T2 distribution) and pore-throat radius (which drives capillary behavior). The hypothesis is the resulting relationship (between the NMR T2 distribution and pore-throat distribution) embedded within a single universal proportionality parameter termed kappa, κ; where:

where σ is the interfacial tension; θ is the contact angle between the fluid interface, and the pore wall, and rneck is the pore-throat radius.

They concluded that the universal scaling factor, κ = 3 psi Hg s seems to work for all clastic reservoirs, and as such making their technique very valuable in exploration wells.

Arogun and Nwosu (2011) tested the Volokitin et al. hypothesis in one of the deep water turbidite reservoirs in Niger Delta, composed of four genetic reservoir units: channel storey axis (CSA), channel storey margins (CSM), inter-channel (ICTB) and mud-rich thin beds (MRTB) units. The genetic reservoir units (simply lithofacies associations) are the result of a practical subdivision of a reservoir into components which have a consistent range of reservoir properties, a consistent external geometry, and a set of log responses (electrofacies) by which they can be consistently recognized. This up-scaling step from lithofacies to genetic reservoir unit (micro to meso-scale) is a key stage in the reservoir geological modelling process. They proposed a scaling factor, κ = 10 psi Hg s as suitable for estimating realistic capillary pressures from T2 distribution against earlier works by Volokitin et al. which postulated a universal scaling factor, κ = 3 psi Hg s. This depicts that the Volokitin “universal” conversion factor was not universal and varies with depositional environments.

In an effort to estimate pore throat radius in uncored reservoir intervals using same deep water dataset from earlier works for the clastic turbidite sequence, various kappa scaling factors within acceptable minimum and maximum limits were evaluated.

Data analysis and model formulation

Figures 1 and 2 present dataset obtained from well logs and laboratory special core analysis (at a net confining stress of 1850–1950 psi) and routine core analysis from 11 core samples at depths between 9000 and 10,000 feet, from the Deep Water Canyon reservoirs within the Tertiary Niger Delta Province. This depicts log motifs for low resistive and low contrast pay. Pore throat distribution were computed using kappa values within acceptable limits to demonstrate their relationship with laboratory mercury injection capillary pressure (MICP) data from a full-bore core. Figure 3 presents the pore throat distribution obtained from laboratory special core analysis employed as reference to the kappa predicted capillary pressure curves expressing the sample unimodality and rock fabric. This indicates a maximum of 24% pore volume accessible to the channel storey axis unit.

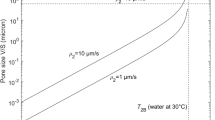

Figures 4, 5, and 6 present pore throat distribution plots obtained from kappa-derived NMR capillary pressures using dataset from same well with mercury injection capillary pressures from the deep water canyon reservoir. The analysis incorporated the Volokitin et al’s algorithm using a multiple regression analysis for kappa values of 2, 3, 5, 7 and 10 psi Hg s. A scaling factor of 2 psi Hg s (see the bottom plot of Fig. 6) indicates appreciable correlation with the measured pore throat radius from MICP dataset compared to existing works for pore body/pore throat definition. Haruna and Ogbe (2017) evaluated these units using different approaches and cross plots for RQI and FZI to ascertain geologic calibration and their impact on 3D reservoir characterization.

Varying the kappa scaling factor demonstrates the inadequacies of using a single proportionality constant in modelling pore throat distribution greater than 10 microns, and thereby questions the proposed existence of a linear relationship between the NMR T2 distributions and measured capillary pressures. As such a single kappa factor is insufficient in characterizing pore throat distribution for reservoir with complex lithologies.

In addition, the existing kappa-based algorithm for transforming NMR T2 distribution to capillary pressures under-predicts the pore volume accessible to pore throat distribution for all Kappa values tested for all cases tested using the Deepwater Clastic Niger Delta dataset.

For all cases of kappa tested as presented in Figs. 4, 5, and 6, a maximum of 6.4% pore volume is accessible to the pore throat distribution for same reservoir unit. This denotes a 73% reduction in accessible pore volume compared to the laboratory-measured dataset.

In this present work, the laboratory-measured capillary pressures are compared with NMR derived ones for calibration with emphasis on various genetic units. Preliminary analysis aimed at validating the existence of the proposed relationship (Eq. 1) between measured capillary pressures and inverse NMR T2 distribution after Volokitin et al. indicate a nonlinear relationship as demonstrated in Fig. 7.

If Volokitin assumption as shown in Eq. 1 is valid, the plot in Fig. 7 should have yielded a straight line.

A possible averaging for the kappa proportionality constant for the range of capillary pressures as described above for all dataset shows a negative exponential relationship between measured capillary pressures and inverse of NMR T2 distribution (Fig. 7).

The least squares best fit exponential model to the data as shown using Fig. 7 is then:

where kappa, κ is the shift factor for modelling the individual sample dataset.

Analysis indicate that the linear relationship as embedded within the kappa scaling factor as defined by Eq. 1, only exist beyond certain pressure threshold values.

Application of capillary pressure cutoff delineating the entry pressures for all samples as presented in Fig. 8 demonstrates the aforementioned assertion (Eq. 2).

This implies that Volokitin et al. proposal is not valid for (Pc)cutoff equals zero or negligible; typical in homogeneous and well sorted formations. This is one of the motivations for the current study. A quick look analysis of Fig. 8 also indicates the possible presence of four (4) reservoir zones within the system.

The various values of kappa from Fig. 8 at NMR T2 inverse of 1 are 110, 60, 15 and 3 corresponding to the CSA, CSM, ICTB and MRTB genetic reservoir units respectively. NMR capillary pressures were estimated from the relationship in Eq. 3 above and compared with laboratory-measured dataset.

Figure 9 presents a plot of mercury injection capillary pressures versus NMR predicted pressures using the relationship in Eq. 3. This indicates a good correlation between both parameters at pressures beyond the imposed cut-off pressures.

The results demonstrate the weaknesses of existing methodology in relating pore-body radius (as represented by the NMR T2 distribution) to pore-throat radius (which drives capillary behavior). It suffices then to conclude that there exist no direct linear relationship between the NMR T2 distribution and capillary parameters as proposed by Volokitin et al.

In addition, the constant scaling factor for kappa is insufficient in modelling subsurface capillary pressures/pore throat distribution from NMR T2 logs. This presents a need for improved predictions through local calibration, possibly allowing the scaling factor to vary as a function of rock types (pore size/grain sorting) and influence of clay diagenesis within the clastic system.

The following sub-section presents an analytical methodology for improved capillary pressures and pore throat radius estimation from NMR measurements based on genetic reservoir units’ averages of Kappa for the Niger Delta clastic reservoir as case study.

Flow unit based analytical methodology for NMR-Pc calibration

The following steps were adopted for calibrating capillary pressures obtained from mercury injection pressures (Pc) to NMR T2 values:

-

1.

Reservoir characterization: to integrate the distribution of depositional facies defined by geologic study with the vertical sequence of rock types determined from reservoir quality studies. In principle, the focus is to delineate zones composed of similar rock types that are in hydrodynamic communication. Each flow unit possesses stratigraphic continuity with a strong relationship to pore geometries and capillary characteristics (entry pressures and irreducible water saturation).

-

2.

Invert the NMR T2-distribution in porosity units (v/v)/time-domain Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) pulse echo decay to a standard T2-parameter-domain distribution (ms). Coates et al. (1999) presented how the processed T2 distribution with T2-bins ranging on a logarithmic scale depending on the NMR tool type and acquisition type that generates the T2 distribution data.

-

3.

Generate the cumulative T2 distribution (sum of amplitudes) curve. Altunbay et al. (2001) and Chen et al. (1998) demonstrated the relationship between core NMR measurements and NMR log data as presented in Fig. 10.

Illustration of T2 cutoff estimation process with NMR core measurements. a Incremental distribution and b cumulative distribution (after Chen et al. 1998)

Usually the T2 cutoff or SBVI methods are typically used to partition the BVI of the T2 distribution. As demonstrated in the cumulative porosity distribution plot, the partitioning presents estimates for T2 cutoff and bulk volume irreducible (BVI). As illustrated, this corresponds to the maximum cumulative porosity where irreducible water saturation from the core NMR measurement intercepts the NMR T2 log.

-

4.

Calibrating NMR T2 distribution to laboratory-measured MICP dataset.

Equation 4 indicates an inverse proportionality between capillary pressures and pore throat radius r; and recall that the T2 distribution is directly proportional to pore-body radius, Rb. It suffices to infer that T2 distribution and capillary pressures are associated through the pore geometry provided there exist a correlation between pore-body and pore-throat size. For the clastic system, the grain size determines both the pore body and the pore throat radius, and as such a relationship between Rb and r can be expected.

Combining Eqs. 2 and 4, we obtain:

where β relates the pore-throat radius to the pore-body radius.

Note: beta (β) and rho (ρ) are obtained from the spherical pore assumption with the inclusion of surface relaxivity (rho) in the T2 equation. See Table 1 for typical clastic pore geometry and surface to volume analysis employed for the analysis.

The expression in Eq. 5 can also be summarized as:

where κ is defined as:

The terms \(\rho\) and β vary with the mineral composition of the rock, and in a brine-wet rock, T2 in smaller pores will be less than T2 in large pores; consequently, identical pore water in different rocks can have a wide range of relaxation times because of variations in \(\rho\).

Sørland et al. (2007) proposed the average surface relaxivity \((\bar {\rho })~\) based on laboratory CPMG measurement for transforming the T2 to pore body distribution. The \(\bar {\rho }\) is expressed as:

with εi being the volume fraction of pores with (S/V)i, and n is the number of bins for the NMR measurement.

Based on classification from the various units, average Kappa values were estimated using the proposed relationships shown in Eqs. 7 and 8 above.

The calibrated kappa functions were further used to generate capillary pressures from the NMR T2 distribution.

Jin et al. (2012) proposed a methodology for computing the wetting-phase saturation (Sw) corresponding to the NMR-derived capillary pressures from the NMR T2 distribution as:

where \({\varphi _T}\) is the total porosity; \(\varphi ({T_2})\) is the T2 distribution in porosity units, and T2min is the minimum T2 of the distribution.

Applying NMR T2 cutoff to delineate the bulk volume irreducible (BVI) from the bulk volume moveable (BVM) presents an improved calibration of NMR-derived saturation to measured data, over existing works by Jin et al. (2012). This approach is based on the assumption that the smaller pore spaces are occupied by the wetting phase alone, and the irreducible water (Swirr) saturates the pores with T2 less than a threshold relaxation time (T2cutoff), whereas the fluids in pores with T2 > T2cutoff are movable.

Hence, the saturation of water at a height above FWL can be given by:

where \(\alpha ~=~\frac{{2\sigma \cos \theta }}{{3\rho {T_2}h({\rho _{\text{w}}} - {\rho _{{\text{HC}}}})g}}\); and \(\kappa\) is the genetic units averages of kappa.

NOTE: Due to the shallow depth of investigation of the NMR logging tool, the water saturation is the flushed (invaded) zone.

-

5.

NMR derived capillary pressure curve does not necessarily match the measured curve. Altunbay et al. (2001) demonstrated that the results differ in the entry capillary pressures and irreducible water saturation. This is due to the fact that the capillary pressure curves goes down to the irreducible water saturation (Swirr) on the abscissa while the NMR derived curve goes almost to zero water saturation. The Swirr contains up to the BVI fluid volume. To achieve a match between the NMR derived versus the laboratory-measured capillary pressure curve, it is necessary to rescale the NMR saturation. As a measure of the fit quality for a given value of kappa, we introduced the average saturation error between the constructed NMR capillary pressure curve and the corresponding MICP. This saturation is the root mean square (RMS) average of saturation differences: \({S_{\text{w}}}({P_{\text{c}}}) - {S_{\text{w}}}({\text{Kappa}} \cdot T_{2}^{{ - 1}})\). A plot of the measured water saturation (\(S_{{\text{w}}}^{\prime }\)) versus NMR saturation (Sw-NMR) demonstrates a possible linear relationship between the response and predictor variable with a constant shifting parameter for the various genetic reservoir units. The shift parameters were calibrated for specific reservoir units, resulting in a master equation or averaged curve. Therefore, the calibrated NMR saturation (\(S_{{\text{w}}}^{\prime }\)) can be expressed in the form of a linear relationship as follows:

$$S_{{\text{w}}}^{\prime }=A+B({S_{{\text{w-NMR}}}}+C),$$(11)where “A” and “B” are constants, while “C” is a genetic unit based shifting scaling parameter.

However, the modification of Swi results in altered initial T2 cut-off, and hence \(S_{{\text{w}}}^{\prime }\) increases beyond 100%, which requires further recalibration to measured saturation.

NMR-Pc calibration: application to reservoir characterization using the Niger Delta deepwater turbidites as case study

Data gathering and reservoir quality characterization

Figures 1, 11 and 12 present dataset from the Deep Water Canyon reservoirs within the Tertiary Niger Delta Province. Detailed laboratory core analysis and description for lithofacies definition, understanding the environment of deposition, and petrographic studies were made possible with assistance from Shell Nigeria. Conventional as well as NMR T2 spectrum logs were also obtained from same cored interval.

In this present work, the laboratory-measured capillary curves are compared with NMR derived ones for calibration with emphasis on various genetic units.

Petrographic data gives focus to pore bodies—their size, shape and relationship to rock fabric. MICP data on the other hand provides data on pore throats. The two data types are complementary and comparisons between the data types give extra insights into the pore system. A comparison of petrographic analysis, T2 distribution and MICP data together provides answers to following questions: (i) which pore type(s) provides the main pore connectivity and hence mostly impacts permeability? (ii) What is typical about pore throat size signatures for a particular genetic reservoir? (iii) What is the spatial architecture of the pore systems in various distributions? and (iv) How can we quantify the porosity composition per pore system? Table 2 presents the rock quality/petrofacies classification based on pore throat ranges identified from petrographic and sieve analysis as well as pore throat radius distribution from mercury injection capillary pressures. The 2 µm cutoff criteria (Onuh et al. 2015) for delineating micropores from macropores for the clastic system is also applicable to the dataset. This serves as a basis for preliminary definition of rock fabric and genetic units for all samples; and for classification of the dataset into groups of different porosity ranges.

Figures 11 and 12 demonstrates that for a given T2 distribution at any given depth, a corresponding pore-body can be estimated as illustrated in Eq. 5. For the clastic system, the grain size of a given distribution also has a closely linked pore-size distribution. This in turn implies that NMR relaxation times will follow a distribution controlled by grain size distribution as demonstrated in Figs. 11 and 12. This presents the relationship between pore bodies as defined by the NMR T2 distribution, petrographic grain size distribution and pore throat embedded in capillary pressures from mercury injection.

Multiple pore types will have their individual size distribution and each distribution will translate into individual T2 distributions controlled by the pore sizes and their surface to volume ratio. Under this hypothesis, the observed T2 distribution will be the sum of multiple distributions, each corresponding to the size distributions of individual pore types. Identifying these individual distributions reveals information on pore types.

Detailed core analysis for lithofacies association from the available dataset depicts the four (4) prevailing genetic reservoir units within the deep water asset. Table 3 below presents the classification adopted for this study.

It is critical to understand that flow units may or may not correspond exactly with the depositional facies/genetic reservoir units defined in the geologic study. Figure 13 presents a plot of the normalized cumulative reservoir quality index (RQInc) versus depth employed for delineating the reservoir into several zones by observing changes in the slope. Consistent zones are characterized by straight lines with the slope of the line indicating the overall reservoir quality within a particular depth interval. A lower slope indicates a higher reservoir quality and vice versa. Hydraulic units delineation based on the normalized reservoir quality index shows a strong correlation with the genetic reservoir units’ classification and geologic core description.

The total dataset was subdivided into four flow units. The integration of reservoir quality information, engineering data, and field performance history into the detailed geologic description of the reservoir is essential for any successful reservoir characterization study. Figure 14 presents a plot of mercury injection capillary curves delineating the various reservoir units. This shows a strong correlation between the genetic units association, rock quality and capillary parameters. This is evident of clay mineral diagenesis and its influence on grain size distribution/sorting. As such a relationship between pore bodies and pore throats will bear practical significance and relevance when constrained to the various genetic reservoir units.

Measured capillary pressure curves indicating a relationship between the various hydraulic flow units and capillary parameters. Reservoir quality properties increase from the black curve (HFU 1—mud rich thin bed units) with high irreducible water saturation and entry pressures to the green curve (HFU 4—channel storey axis units) with low Swirr and Pentry

Calibrating NMR T 2 distribution to MICP dataset

Equation 6 depicts a relationship between measured capillary pressures and the NMR T2 distribution. A semilog plot of laboratory-measured capillary pressure data and the inverse NMR T2 array data as presented in Fig. 15 for the channel storey axis reservoir unit, demonstrates an existing relationship with need for recalibration. Key emphasis is the relationship between end point capillary parameters (entry pressures and irreducible water saturation).

In an attempt to calibrate the NMR T2 log to measured capillary dataset, cumulative T2 distribution curves were generated for individual dataset belonging to the four (4) reservoir units. The emphasis is to establish key parameters relating capillary pressures to NMR T2 distribution, and the cut-offs for estimating the FFI, BVI, corresponding Swirr and total porosity. Figure 16 presents plots of NMR T2 distribution indicating cumulative and incremental porosity using dataset from HFU 4. The figure estimates the bulk volume irreducible (BVI) for Swirr modelling and total porosity available to the free and bound fluid volumes. The figure depicts a BVI and total porosity of 0.06 and 31%, respectively.

This confirms a good correlation between the NMR derived Swirr and total porosity with the laboratory-measured parameters. This was applicable to all dataset available for the study.

Based on classification from the various HFUs, average kappa values were estimated using the proposed relationships shown in Eqs. 7 and 8 above. Nonlinear regression analysis for confidence interval and limits for kappa applicability for the various genetic reservoir units were performed. Table 4 presents averages of kappa values for the various genetic reservoir units defined for the deep water turbidite system. The calibrated kappa functions were used as input to generate capillary pressures from the NMR T2 distribution.

The modified relationship (Eq. 10) after Jin et al. (2012) was used to compute the wetting-phase saturation (Sw) corresponding to the NMR derived capillary pressures. Figure 17, 18, 19, and 20 display plots of capillary pressures from NMR T2 distribution and MICP.

As demonstrated for all dataset; NMR derived capillary pressure curve does not necessarily match the measured curve. The results differ in the initial entry capillary pressures and irreducible water saturation. This is due to the fact that the capillary pressure curves goes down to the irreducible water saturation (Swirr) on the abscissa while the NMR derived curve goes almost to zero water saturation. The Swirr contains up to the BVI fluid volume.

To achieve a match between the NMR derived capillary pressure curve and the laboratory-measured curve, it is necessary to rescale the NMR saturation. This involves correction for root mean square (RMS) average of saturation differences between the NMR derived and laboratory-measured saturation. As a measure of the fit quality for a given value of kappa, we introduced the average saturation error between the constructed NMR capillary pressure curve and the corresponding MICP.

This saturation is the root mean square (RMS) average of saturation differences: \({S_{\text{w}}}({P_{\text{c}}}) - {S_{\text{w}}}({\text{Kappa}} \cdot T_{2}^{{ - 1}})\).

Figure 21 present a plot of the measured water saturation (\(S_{w}^{\prime }\)) versus NMR saturation (Sw-NMR) for the inter-channel thin bed reservoir unit demonstrating a possible linear relationship between the response and predictor variable with a constant shifting parameter for the various genetic reservoir units.

The shift parameters for the predictor variable were calibrated for the specific genetic reservoir units within the deep water turbiditic environment. For this reason, the procedure is applied to several samples from which an average value for each coefficient can be obtained as shown in Fig. 22 for \(S_{w}^{\prime }\) versus Sw-NMR plot. This is equivalent to delivering a master equation or averaged curve.

Therefore, the calibrated NMR saturation (\(S_{w}^{\prime }\)) can be expressed in the form of a linear relationship as follows:

where A = − 0.2023, B = 0.9893, and; C = genetic unit based shifting scaling parameter (see Table 5).

Figures 23 and 24 present plots of predicted capillary pressures obtained from NMR log data and measured MICP. This demonstrates appreciable match with the measured core analysis dataset for all genetic reservoir units analyzed within the depositional environment. This was applicable to all dataset available for the study.

Conclusions

-

1.

A constant scaling factor for kappa is insufficient in modelling subsurface capillary pressures from NMR T2 logs.

-

2.

An improved approach for estimating primary drainage capillary pressure curves from NMR T2 transversal distribution using a genetic unit based kappa scaling factor is developed using dataset from clastic origin.

-

3.

Kappa scaling factor for capillary pressure and NMR logs calibration vary as a function of pore size/grain sorting, rock types (petro-facies) and influence of thermal gradient on clay diagenesis within the clastic system.

-

4.

NMR derived capillary pressure curve does not necessarily match the measured curve due to the RMS averages of saturation differences. Additional curve fitting procedure is required for accurate capillary pressure modelling. This can be obtained by either using a fitting procedure that gives an average scaling factor for matching with measured data or the proposed modification after Jin et al. (2012).

-

5.

The genetic unit averages of pseudo normalized pore-throat radius as input parameter has been developed for applications in the absence of core and NMR log dataset.

References

Altunbay M, Martain R, Robinson M (2001) Capillary pressure data from NMR logs and its implications on field economics. SPE 71703. Society of Petroleum Engineers, New Orleans

Arogun O, Nwosu C (2011) Capillary pressure curves from nuclear magnetic resonance log data in a deepwater turbidite Nigeria field—a comparison to saturation models from SCAL drainage capillary pressure curves. Society of Petroleum Engineers. Abuja

Chen S, Ostroff G, Georgi DT (1998) Improving estimation of NMR Log T 2 cutoff value with core NMR and capillary pressure measurements. In: SCA international symposium, The Hague, SCA-9822

Coates G, Xiao L, Prammer M (1999) NMR logging: principles and applications. Halliburton Energy Services, Houston

Haruna OM, Ogbe DO (2017) Modified reservoir quality indicator methodology for improved 2017 hydraulic flow unit characterization using the normalized pore throat methodology (Niger Delta field as Case Study). JPEPT 7(2):409–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-016-0297-8 (Springer Publishers)

Jin G, Manakov A, Chen J, Zhang J (2012) Capillary pressure prediction from rock models reconstructed using well log data. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, Texas, USA. SPE 159761

Onuh HM, David OO, Nwosu C (2015) Genetic units based permeability prediction for clastic reservoirs using normalized pore throat radius (Niger Delta as Case Study). IJPE, Inderscience Publishers, vol 1, pp 245–270

Sørland GH, Djurhuus K, Widerøe HC, Lien JR, Skauge A (2007) Absolute pore size distributions from NMR. J Basic Princ Diffus Theory Exp Appl Diffus Fundam 5:4.1–4.15

Volokitin Y, Looyestijn W, Slijkerman WFT, Hofman JP (2001) A practical approach to obtain primary drainage capillary pressure curves from NMR core and log data. Petrophysics 42:SCA-9924

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the management of Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC), Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR), and the Petroleum Technology Development Fund (PTDF), Nigeria for their support and permission to publish this article. Special thanks to the SPDC petrophysics and geosolution team who were involved in discussions that made this possible. We would also like to show our appreciation to our colleagues who reviewed this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Onuh, H.M., Ogbe, D.O. Genetic units averages of kappa for capillary pressure estimation from NMR transversal T2 distributions (Niger Delta as field case study). J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 9, 1161–1174 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-018-0544-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-018-0544-2