Abstract

Do conceivability arguments work against physicalism if properties are causal powers? By considering three different ways of understanding causal powers and the modality associated with them, I will argue that most, if not all, physicalist powers theorists should not be concerned about the conceivability argument because its conclusion that physicalism is false does not hold in their favoured ontology. I also defend specific powers theories against some recent objections to this strategy, arguing that the conception of properties as powerful blocks conceivability arguments unless a rather implausible form of emergence is true.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Do conceivability arguments work against physicalism if properties are causal powers? A negative answer to this question would be extremely significant, not simply from a metaphysical point of view, but also because the conceivability argument has implications for the scientific methodology required to explain consciousness, the ontology one might postulate to do so, and even whether consciousness can be explained at all. If philosophical zombies are possible, such that there could be a being physically identical to a conscious human subject which lacked conscious experience, then not only are most forms of physicalism false but we are faced with a hard problem of explaining consciousness which cannot be tackled by neurophysiology or cognitive psychology in their current forms. Even if one takes an optimistic view that the hard problem can be solved, a paradigm shift would be needed in order to explain consciousness which radically altered either the entities and structures these sciences postulate, physical theory more broadly, or the experimental methods which they use.

Powers theorists have suggested several reasons why, given their favoured ontology, this paradigm shift will not be necessary, either because the conceivability argument does not apply to certain metaphysical accounts of the world which arise in virtue of a commitment to properties having their causal powers essentially or necessarily, or because some such accounts have in effect achieved such a paradigm shift already by clarifying how phenomenal properties are essentially incorporated in the natural world. If they are right, the conceivability argument presents no a priori obstacle to the empirical explanation of consciousness in physicalist or naturalistic terms. By considering three different ways of understanding causal powers and the modality associated with them, I aim to generalise these conclusions about specific versions of powers theory to argue that most, if not all, physicalist powers theorists should not be concerned about the possibility of philosophical zombies, nor more generally about the possibility of zombie worlds, physically indiscernible worlds which lack conscious properties entirely. In doing so, I will examine some of the recent claims about powers theory and objections to them, as well as considering novel ways in which powers theories may be thought to resist the conclusion of the conceivability argument that physicalism is false.

I will not be arguing for any version of powers theory in this article; rather, I will investigate the implications of powers theory should one accept it.Footnote 1 It should also go without saying that by investigating whether powers theories can avoid conceivability arguments against physicalism, I am not suggesting that all powers theorists are, or should be, physicalists, nor does the success of my argument entail that powers theories are inconsistent with dualism. I presume that powers theorists will have the same range of commitments to dualism or monism in the philosophy of mind as any other group of philosophers, and there may be other arguments against physicalism which do apply to powers theories and are unaffected by what I have to say.

1 A note about ontology and terminology

Under the umbrella term ‘powers theory’, I will include any theory that regards properties as having their causal or nomic roles essentially or necessarily and as not being reducible to entities which do not. (One could distinguish necessarily and essentially (Fine, 1994) but this distinction is not important to my argument, so I will overlook it here.) The terminology in current use for this family of entities is varied and thereby apt to cause confusion, with some philosophers talking about causal powers while others prefer ‘potentialities’, ‘dispositions’ or ‘dispositional properties’ (with the latter two sometimes distinguished (Bird, 2007, Borghini & Williams, 2008, Azzano, 2019)),Footnote 2 which leads to talk of ‘dispositionalism’ about properties or the various accounts of modality which are based upon irreducibly dispositional properties or dispositions.Footnote 3 In the main, it will be possible to overlook subtle differences between members of this family of entities for the purposes of my argument so I will mainly stick to talk of powers but (following the conventions of other authors) I occasionally use ‘dispositional property’ instead.Footnote 4 (I will remain neutral about whether or not such dispositional entities can also be given a conditional analysis.)

2 Conceivability arguments

From their inception (Kripke, 1980; Chalmers, 1995, 1996, 1997), conceivability arguments have undergone various refinements to deal with objections and physicalist responses (Chalmers, 1999, 2002, 2010).Footnote 5 I will be concerned with Chalmers’ most recent articulation of the conceivability argument (2010, Chapter 6) which I will briefly explain before considering where different powers theories stand with respect to this argument.Footnote 6

Let P be all physical facts and Q an arbitrary phenomenal fact or facts. Call the proposition that there can be P without Q (that is, the proposition that P & ¬Q) the Zombie Hypothesis. We can follow Chalmers (2010, Chapter 6) and articulate the conceivability argument as follows (further explanations of terms will follow):

-

1)

P & ¬ Q is conceivable (in the right type of way).

-

2)

If P & ¬Q is conceivable, then P & ¬Q is primarily possible (1-possible).

-

3)

If P & ¬Q is 1-possible, then P & ¬Q is secondarily possible (2-possible) or Russellian monism is true.

-

4)

If P & ¬Q is 2-possible, then materialism/physicalism is false.

-

So: Materialism/physicalism is false or Russellian Monism is true.

The distinctions here are important to the soundness of the argument (if indeed it is sound), or at least to maximise its plausibility. First: the conceivability in question must be ideal primary conceivability (either positive conceivability or negative conceivability); that is, on ideal rational reflection, one must either be able to conceive of P & ¬Q being true or at least not be able to rule out its truth by a priori reasoning (Chalmers, 2010, p. 148).Footnote 7 This conceivability entails 1-possibility, in the sense that it entails that there is a possible world which verifies P & ¬Q, although it may not satisfy it as it would have to do for P & ¬Q to be 2-possible. For instance, if Kripke is right, there is no world in which ‘Water is not H2O’ is satisfied because water is identical to H2O. However, there is a world which verifies the claim that ‘Water is not H20’: it is the world in which colourless, odourless liquid which falls from the sky as rain and fills rivers and lakes is a chemical compound which does not consist of two hydrogen atoms and an oxygen atom. This could be an XYZ world, for example, and there is a sense in which the actual world could have been like this. In such a world, we would epistemically be in the same situation as we would be if water were not actually H2O, and so the statement that ‘Water is not H2O’ would be verified, but such a world would not satisfy this statement because it would not be a world in which water has a different molecular structure from the structure it actually has. Of course, that P & ¬Q is 1-possible is not sufficient for the falsehood of physicalism: it simply tells us that there is a world in which physicalism is false but it is not like our world. What is needed is the 2-possibility of P & ¬Q: a world in which the physical facts obtain but the phenomenal one does not; a zombie world, in other words.

The principle which underlies Chalmers’ third premise is that 1-possibility entails 2-possibility, except in a specific group of cases which he gathers together under the umbrella term ‘Russellian Monism’ (2010, pp. 133–7, 151–2). If a statement can be verified, then there is a possible world which satisfies it, except in ontological systems where the satisfaction of P also essentially involves the satisfaction of Q. His central claim here is that the only cases in which P & Q is true in one world (w1, say) and P & ¬Q is verified in some worlds but not satisfied by any them are those cases where the truth of P is determined by the structural arrangement of physical properties (their relations to each other) and the truth of Q is determined by the intrinsic nature of the properties which determine the truth of P. In such cases, the worlds which verify P & ¬Q have the same structure as w1 – so P is verified – but the properties within them lack the requisite intrinsic nature which determines the truth of Q. However, while P is verified by such worlds it is not satisfied, and so P & ¬Q is not satisfied either.

Given the closeness of the relationship between what makes P true and what makes Q true, worlds which satisfy P & ¬Q cannot exist: they would have to be worlds with the same physical properties as w1 in which such properties lack their intrinsic nature and that is impossible. Every world which satisfies P also satisfies Q, so 1-possibility does not entail 2-possibility in a Russellian Monist ontology.

Underlying the conceivability argument then are two principles: the Conceivability Principle which underpins the move from conceivability to 1-possibility in premise 2, and the Principle of (Modal) Plenitude which permits the move from 1-possibility to 2-possibility in premise 3. I have not defended these principles here (see Chalmers, 2009, p. 327), but there will be reason to return to their plausibility in the discussion of how powers theories fit in with the conceivability argument.

2.1 Powers and the conceivability argument

For the purposes of this discussion, it will be useful to subdivide powers theories into those which regard properties as being both powerful and qualitative and those which regard properties as being purely dispositional or pure powers. Let us call these powerful qualities theories and pure powers theories respectively.Footnote 8 A second round of distinctions subdivides the pure powers theories according to their modal commitments into actualist theories which treat physical (or natural) and metaphysical possibility as being coextensive and powers theories which accept that there are some metaphysical possibilities which are not physically possible.

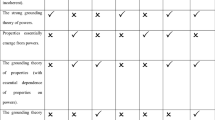

A third distinction cross-cuts the first two according to what kinds of things powers or powerful qualities are, ontologically speaking: one can take a Platonist view in which powers are transcendent universals which can exist uninstantiated (Bird, 2007, Tugby, 2013, 2015, 2017, Giannini & Tugby, 2020) or a broadly-speaking naturalist one in which powers are, or are ontologically derived from, immanent universals or tropes.Footnote 9 For the most part, I will presuppose naturalism in my discussion, since the differences in ontological background commitments between Platonists and naturalists do not significantly affect the way in which theories of powers interact with the conceivability argument if physical and metaphysical possibility are coextensive. However, they diverge in their treatment of metaphysical possibility and so I will consider naturalism and Platonism separately on this point. (Further distinctions between views will be signposted as and when they occur.) These families of theories interact with the conceivability argument in distinctive, although not mutually exclusive, ways but each is consistent with the view that philosophical zombies are not 2-possible; thus, they are consistent with some form of physicalism and the physicalist explanation of consciousness. Furthermore, the only interpretations which do permit the possibility of zombies either require an implausible form of emergentism, or they result in a problem for physics which is analogous to the hard problem of consciousness. In the latter case, the problem of consciousness is either not a special case or the conceivability argument should be rejected as it makes problems with explanation ubiquitous. I will consider each of these accounts in turn.

3 Powerful qualities

3.1 Powerful qualities and Russellian monism

When used in Chalmers’ sense (2010, pp. 133–7), ‘Russellian Monism’ includes views in which the structural, dispositional properties of physics which satisfy P are grounded by categorical bases which satisfy Q, or in which the structural physical properties satisfying P have intrinsic natures which satisfy Q. The term is used because it includes or is close to Russell’s account of the relationship between consciousness and the physical (1927). Not all the proponents of the views which Chalmers includes under this term would refer to themselves as ‘Russellian Monists’, nor does one need to be a physicalist to accept a version of this account of the relationship between the causal or structural features of properties and their intrinsic natures.

From the point of view of their interaction with the conceivability argument, powerful qualities theories behave in a similar way to Russellian Monist theories in Chalmers’ rather broad sense of the term and might be considered versions of it (although their supporters do not always regard them as such).Footnote 10 These theories, in which properties are essentially dispositional and also qualitative, vary in their accounts of the relationship between the qualitativity and the powerfulness of propertiesFootnote 11; but by treating powerfulness and qualitativity as identical or as necessarily inseparable in some way, they interact with the conceivability argument in a similar way to Russellian Monism, which, as Chalmers notes, is slightly complicated (2010, pp. 134–5). Insofar as the possibility of zombies is concerned, the powerful qualities theorist can either argue that the truth of the zombie hypothesis is not conceivable (Carruth, 2016) or, as in the case of Russellian Monism, that the move from 1- to 2-possibility cannot be made. However, these strategies affect the soundness of Chalmers’ 2010 version of the conceivability argument (as stated in section 3) in different ways.Footnote 12 If one adopts the former strategy and argues that premise 1, the conceivability of P & ¬Q, should be rejected because of the nature of powerful qualities (Carruth, 2016), the conceivability argument would no longer be sound. On the latter strategy, soundness is retained despite the failure of the move from 1- to 2-possibility because premise 3 is made true by its innocuous second disjunct: Russellian Monism is true. As such, the conceivability argument could be regarded as an argument for Russellian Monism, and thus for the powerful qualities theories under consideration. (If one considers earlier versions of the conceivability argument which do not make allowances for Russellian Monism, the conceivability argument would no longer be sound given an ontology of powerful qualities on either strategy.) On either strategy, powerful qualities can be used to resist both the possibility of zombies and the conceivability argument’s conclusion that physicalism is false (Heil, 2003, p. 248; Carruth, 2016).

3.2 How good is the powerful qualities response to the conceivability argument?

One might be concerned that these responses are too quick. First, one might be concerned that the qualitativity of powerful qualities is not of the same sort as the qualitativity of conscious experience. Second, one might not yet be convinced that powerful qualities theories ensure that any set of properties which act as truthmakers for P also act as truthmakers for Q. Third, one might worry that there is a relevant disanalogy between powerful qualities theories and Russellian monism, and that the powerful qualities response to the conceivability argument conceals a contentious assumption about the dispositional nature of the physical and the qualitative nature of the phenomenal; namely, that the dispositional/qualitative distinction mirrors the physical/phenomenal one. I will consider these difficulties in turn.

3.2.1 Qualitativity and phenomenal consciousness

The nature of the qualitativity of powerful qualities is not entirely clear, especially if that qualitativity is intended both to determine the phenomenal feel of conscious experience and to be associated with all other properties, including fundamental ones, of which we are not perceptually aware. (This point is especially troubling for Heil (2003, 2012), since for him ‘real properties’ only include the fundamental physical ones.) One might both doubt whether all properties are in fact intrinsically qualitative and be concerned about how such qualitativity, if it exists, determines conscious experience. These questions perhaps pose the greatest challenges to the plausibility of powerful qualities as an account of consciousness in the physical world, but they are not so pressing here, since they are tangential to our current concerns, and so I will not explore them in this paper. In the context of this specific discussion of the conceivability argument, we are not trying to establish that powers are qualitative, we are investigating the implications of their being so. If the qualitativity of powerful qualities did turn out to be unsuitable to account for phenomenal experience, then they are unsuitable candidates to be the ontological background of the explanation of the relationship between the physical and the conscious mind. However, the evaluation of exact proposals about how powerful qualities, or indeed other powers theories, explain consciousness are also not the concern of this paper; rather, we are concerned with whether such ontological theories would be susceptible to the conceivability argument. Powerful qualities theories may still fail to be good explanations of consciousness for other reasons.

However, before we postpone discussion of the concerns of this section and move on, it is worth noting that the supporter of powerful qualities could mitigate the worries about whether the qualitativity of powerful qualities could play a role in the metaphysical explanation of consciousness, since there are at least three ways in which we could understand the qualitativity of powerful qualities as being constitutive of, or as bringing about, phenomenal facts about consciousness. First and second, in terms familiar from panpsychism, one could suggest that powerful qualities are either all genuinely phenomenal properties or that they are proto-phenomenal properties which somehow combine to produce phenomenal as well as physical truths. (Chalmers, 1996; Chalmers, 2015) Such theories will face the usual obstacles which panpsychist theories face: the first having to deal with reservations about the ubiquity of conscious experience, and the second concerning how proto-phenomenal properties combine to produce the unified field or stream of consciousness which is familiar from our subjective conscious experience.Footnote 13 However, neither position is worse off than other panpsychist theories and furthermore, in combining (or identifying) qualitativity and powerfulness in each and every property, they avoid objections directed at some versions of Russellian Monism about how these different fundamental aspects of reality relate. The third strategy would be to note that the powerful qualities theorist does not have to be committed to panpsychism or panprotopsychism, since one could deny that the qualitativity associated with powerful qualities is uniform. On this view, phenomenal properties would be a subset of powerful qualities, while other non-phenomenal properties would still be intrinsically qualitative but would not be associated with consciousness or the production of conscious experience.Footnote 14 (This third, mixed view of the qualitativity of powerful qualities might generate a further philosophical difficulty about the nature and explanation of consciousness; namely, what distinguishes phenomenal from non-phenomenal powerful qualities. However, I will set aside this complication here, since it not directly relevant to the matter at hand.)

3.2.2 Conceivability (again)

The second problem is a call for reassurance that theories of powerful qualities genuinely avoid the conceivability argument; in particular, that a set of properties which makes P true will automatically act as truthmakers for Q. The difficulty envisaged is that the ontology of powerful qualities might permit a version of the inverted (or even absent) qualia arguments: The physical properties of the actual world make P & Q true, but perhaps there could be a set of properties which makes P true and has a different intrinsic qualitative nature, or involves no intrinsic qualitative nature as far as consciousness is concerned (that is, there are proto-phenomenal qualities but they do not combine to act as truthmakers for any phenomenal truths). However, this objection fails.

First, one can reiterate Chalmers’ point that such a possible scenario would verify P but not satisfy it: the properties involved would be different because they would lack the intrinsic qualitative nature of the properties which satisfy P in the actual world. So we cannot move from 1-possibility to 2-possibility and the conceivability argument is neutralised at premise 3, since the powerful qualities theory is analogous to Russellian Monism. But one might still be concerned that there could be properties which verify P – that is, they capture all the structural relations of the physical world because they have the same causal roles as all actual physical properties – and yet they do not have the same intrinsic qualitative nature. Such an ontology would not, strictly speaking, satisfy P & ¬Q but, as in the Kripkean examples which appear to satisfy ‘Water is not H2O’, there would be an alien world in which all the physical facts were the same as the physical facts of the actual world and yet the phenomenal facts were different. It is this world we are thinking about when we worry about whether the zombie hypothesis P & ¬Q is true.

However, it is not clear that such worries are coherent on any theory of powerful qualities, since the qualitativity of properties would have to be individuated in a more fine-grained way than their powers for the conceivability argument to gain traction again in this way. In particular, the scenario described above requires that properties could be identical with respect to their causal powers and distinct with respect to their qualitativity. Thus, this is not a genuine difficulty for any accounts of powerful qualities which adhere to the identity thesis (which includes most actual accounts of powerful qualities, including the one employed by Carruth (2016) in his argument against premise 1)Footnote 15: on these views it is impossible for dispositionality and qualitativity to come apart. Given the identity thesis, one could maintain that the scenario described is not just secondarily impossible, it is also inconceivable.

A world in which P & ¬Q is true would only be possible if having a particular causal role were necessary to being a property S but not sufficient, so that there could be a distinct property T with an identical causal role to S. In such a case, the qualitativity of S and T could be distinct, while their causal roles were identical. (Such an account of properties would still be necessitarian about a property’s causal role, in the sense that the properties would retain their respective causal powers in all possible situations, but it would allow distinct properties to have the same causal role necessarily.) In this case, while S is instantiated in a world which satisfies P & Q, T could be among the set of properties which satisfies P & ¬Q, and it seems that the zombie hypothesis is a genuine worry because we are concerned that our S-world could be a T one. (One might still object that this is not a genuine worry. There will be more on this question later.)

However, although there is logical space for an account of powerful qualities in which causal role is necessary but not sufficient for the identity of a property, this has no supporters among the proponents of powerful qualities. One reason for this is that powerful qualities theories are based on a conception of properties as essentially dispositional, such that identity of causal power is both necessary and sufficient for sameness of property just as it would be if properties were pure powers. (If this were not the case for pure powers, distinct properties would be indiscernible from each other since the nature of a property is exhausted by its causal role.) Powerful qualities theories have inherited the dispositionalist commitment to identifying and individuating properties on the basis of what they can do; sameness of causal power is both necessary and sufficient for sameness of property. Thus, qualitativity cannot be more fine-grained than causal power and examples like the S and T in the previous paragraph are ruled out. Although there is disagreement among the proponents of powerful qualities about how finely grained qualitativity is, there can never be a case where causally identical properties have distinct qualitative natures. One might think that each distinct power has its own qualitative nature (or, better but more awkwardly, is a particular qualitative nature) which other properties do not share. Alternatively, one might take the qualitativity to be more coarse-grained than this, such that properties with distinct dispositional natures have the same qualitative nature, moving to the extreme case in which the qualitativity associated with powers is a generic quality such as that required to make the property space-filling (Schroer, 2013). On all these views in which the conception of powerful qualities is derived from that of powers, it is not possible to have two properties S and T which have the same causal power and distinct qualitativity, such that S and T could (partially) ground the same physical truths and diverge in which phenomenal truths they played a role in determining. Worries about the possibility of absent or inverted qualia are unfounded.

3.2.3 Taylor’s objection

Henry Taylor (2017) has argued that powerful qualities responses fail because they require the identification of the physical and the dispositional, and phenomenal consciousness with awareness of qualitativity, but that these identities are unfounded. Recall that the zombie hypothesis usually concerns the possibility of a being who is a physical duplicate of a conscious human subject and yet lacks phenomenal properties, or more generally a world in which the physical facts of the actual world are true and yet there are no phenomenal facts (or the phenomenal facts are different); that is, a world in which P & ¬Q is true. The two powerful qualities responses state that such a world is inconceivable or impossible on the grounds that the truth of P & ¬Q would require sameness of dispositional features and difference in qualitative features which is impossible in an ontology of powerful qualities (as discussed above). However, this involves two presuppositions: first, that a physical duplicate is a dispositional duplicate; and, second, that the phenomenal properties which are missing (or different) in the zombie world are missing (or different) intrinsic qualitative natures of physical properties, rather than being non-physical powerful qualities with both qualitative and dispositional features. Only then are the qualitative features missing from the zombie world necessarily the qualitative features of powerful physical properties, making their absence inconceivable or impossible in an ontology of powerful qualities.

Taylor argues that the claim that all and only physical properties are dispositional or powerful is ill-founded and begs the question in the context of the discussion of the mind. (Note that the missing requirement is not that physical properties are only powerful, since that would conflict with the nature of powerful qualities.) The existence of non-physical powerful qualities should not be ruled out a priori, but if it is not ruled out, the powerful qualities theorist is hostage to a new zombie argument: It is possible for X and Y to share all physical properties but to differ in their phenomenal properties because X has some powers (qua non-physical powerful qualities) which Y lacks.

There are a lot of questions raised by this objection and the potential replies to it, and I cannot do justice to all of them in this paper.Footnote 16 Prima facie, Taylor’s observation is a devastating blow to the powerful qualities response unless the powerful qualities theorist can motivate the claim that all and only physical properties are dispositional (in addition to their intrinsic qualitative nature) and that phenomenal properties are not.Footnote 17 However, there are some interesting and important points to note which count against this objection. First, and most importantly, in the context of a general discussion of the applicability of the conceivability argument in an ontology of causal powers, the possibility that phenomenal properties are powers rather than (or as well as) being qualitative is of no import at all. Such a possibility might rule out the powerful qualities responses of this section, but there are other responses couched in terms of pure powers which will cover cases where phenomenal properties (qua phenomenal properties) are powerful. The next two sections of this paper will consider whether the conceivability argument is applicable to pure powers and conclude that, on all but a very controversial conception of the relationship between the physical and the phenomenal, it is not. Thus, even if Taylor is correct that the powerful qualities responses require the identification of the physical and the dispositional and that this identification is untenable, powers theories (including the theory of powerful qualities) may still withstand the conceivability argument.

A second restriction on the scope of Taylor’s objection is that it does not apply to the formulation of the conceivability argument which characterises zombies in terms of their being functional, rather than physical, duplicates of conscious human subjects (or zombie worlds as being functionally, rather than physically, identical to the actual world). This formulation is the one considered by Heil (2003, pp. 243–5), as presented by Chalmers (1995, 1996, 1997) in earlier formulations of the conceivability argument, as well as being the basis of earlier criticisms of functionalism from Block (1978). It is notable too that the conception of phenomenal consciousness as purely qualitative also arises from some of these earlier anti-functionalist arguments: phenomenal properties are what is left out of a functionalist account of the world (Block & Fodor, 1972, Block, 1978).

It is far more plausible to equate the functional with the dispositionalFootnote 18 than it is to identify the physical with the dispositional, and so in an ontology of powerful qualities, functional duplicates could not differ with respect to their qualitative features. The physical duplicates X and Y in the case above are both qualitatively and functionally distinct and so they do not exemplify a zombie case. However, the functional duplicate version of the conceivability argument was initially presented as an objection to functionalism, rather than physicalism, and so responses to it reinstate the former rather than the latter. Nevertheless, this would still be a philosophically significant result, especially for those who support functionalism about the mind, since the functionalist version of the conceivability argument and its relations, the absent and inverted qualia arguments, have been used to show that functionalism is an inadequate account of the ontology of mind and also to motivate belief in the existence of the explanatory gap between conscious and non-conscious entities. The fact that such arguments against functionalism do not work in an ontology of powerful qualities is important, even if the powerful qualities defence of physicalism fails, since this may be enough for sciences such as cognitive psychology to be satisfied that their explanations of consciousness could be sufficient.

Third, it would be premature to think that the powerful qualities responses fail to defend physicalism against the zombie argument since it is not clear that Taylor’s argument succeeds. First, contra Taylor (2017, p. 1899), the powerful qualities theorist does not require the identification of physical and dispositional properties, such that it is necessary that all and only physical properties are dispositional ones. Rather, the response requires that all physical properties are dispositional (although they may also be qualitative, and will be if they are powerful qualities) and that, in the physicalist worlds where P & Q is true, only physical properties are dispositional such that there are no non-physical dispositions in those worlds. This does not rule out the possibility of non-physical dispositions, although one of Taylor’s arguments against the identification of the physical with the dispositional relies on just such a possibility being a problem (2017, p. 1900). However, the mere possibility of non-physical dispositions is not a problem: as Chalmers notes (2010, p. 143), physicalism is compatible with the possibility of dualism in worlds where this is grounded by the existence of non-physical mental entities. The conceivability argument applies in worlds which minimally satisfy P to make P & Q true (Jackson, 1998, p. 26), the idea being that such worlds are compatible with the possibility that P (and nothing else) is satisfied and Q is false. Such worlds do not contain non-physical powers which are not determined by physical powers. So the powerful qualities theorist can allow for the possibility of non-physical powers and move on, since if it is contingently true that physical duplicates of every minimal P & Q world and portions of it are dispositional duplicates, then the powerful qualities responses work. On the other hand, if non-physical, (phenomenal) dispositional properties actually exist in the P & Q world, such a scenario will be covered by the pure powers responses and so consideration of it can be delayed until 4.3.

Finally, Taylor’s second concern about the relationship between the physical and the dispositional can also be allayed. Here he argues that accounts of powerful qualities give us reason to believe that the dispositional characterisation of the physical is inadequate because it omits the qualitativity of physical properties (2017, p. 1901), and he cites leading powerful qualities theorists in his support (Heil, 2012, p. 71; Martin, 2007, p. 63; Strawson, 2008, p. 278). This shortcoming brings it into conflict with the conceivability argument, in which Chalmers urges that P should ‘specif[y] the fundamental features of every fundamental microphysical entity’. If a powerful qualities version of P is to be acceptable, then both qualitativity and dispositionality must be specified. There are two remarks to make here: First, on the identity view of powerful qualities, qualitativity is dispositionality, so a specification of one is a specification of the other and nothing is missed out. Second, like the Russellian monists, the powerful qualities theorists regard the intrinsic natures of properties as being beyond our epistemic grasp when we consider them in physical terms; the existence of their qualitativity is established via a priori arguments (for example, Heil, 2003, Chapter 10). Given this, the powerful qualities theorists can point out that we should accept that one can specify the truthmakers of P without specifying everything about the truthmakers of P; indeed, part of the point of their response is that if (in contravention of the limits of our epistemic position) we were aware of the nature of the qualitativity of fundamental physical properties, we would know a priori that P & ¬Q is contradictory. Thus, the apparent conflict with Chalmers’ remark about specifying the fundamental features which determine P should not be taken seriously. (It is worth noting that Chalmers himself does not stick to the letter of his remark given his support for Russellian Monism as a way to avoid the possibility of zombies (2010, p. 137), since it has the same limitations as those which Taylor notes for powerful qualities.)

I have argued that Taylor’s objections are not effective in neutralising the powerful qualities response to the conceivability argument: first, because the response does not require the strict identification or necessary coextension of physical and dispositional properties; second, because the inability of the physical description of the entities which make P true to capture the qualitative nature of those properties is not a shortcoming and is to be expected in a powerful qualities theory. I have not argued here for the positive claim which the powerful qualities theorist requires, that all physical properties are (at least partially) dispositional, since this is presupposed by the powers theories under consideration in this paper. Furthermore, the response I have given here does not yet deal with the possibility that a minimal P & Q world nevertheless contains non-physical powerful properties, that is, cases where it is actually false that only physical properties are dispositional and so physical duplication will not guarantee dispositional (and thereby qualitative) duplication. In such cases, something other than the powerful qualities responses will be needed; however, the non-physical powers in question will behave like pure powers in virtue of their necessary causal relations with other powers,Footnote 19 and can be dealt with by the arguments of sections 4 and 5.

4 Pure powers and Actualism

Support for dispositionalist accounts of modality or strong necessities can be found in: Martin and Heil (1999), Pruss (2002), Bird (2007), Borghini and Williams (2008), Jacobs (2010), Vetter (2011, 2015) (although see footnote 23 below); Jaworski (2016, 2018). In general, these views are actualist since the irreducible intrinsic modality of powers permits one to provide an account of modality without postulating the existence of possibilia.

Because properties have their respective causal powers as a matter of necessity, each property relates to other properties in the same way in each world in which it is instantiated (different effects are usually thought about as being brought about by a power’s being instantiated in the company of different powers). Thus, causal laws (and other nomic connections, if there are any, such as supervenience or realisation) hold as a matter of necessity: if property S brings about T in the actual world (in specific circumstancesFootnote 21) then it does so in every world in which S is instantiated (in those circumstances). This necessity of causal power will still be the case even if one thinks that powers manifest as a matter of dispositional modality rather than necessity (Mumford & Anjum, 2011a, b, 2018): what S produces in specific circumstances will remain constant across all possible situations; while whether S actually manifests is governed by a modality weaker than necessity.Footnote 22 One might call the necessity which governs the relations between powers ‘natural’ or ‘nomological’ necessity. But, if one accepts a form of actualism such that the only powers which exist are those instantiated in the actual world, then this natural necessity is equivalent to metaphysical necessity since the nomic connections of the actual world hold in all possible situations. It is these necessities which Chalmers calls ‘strong necessities’. The existence of strong necessities makes premise 2 of the conceivability argument – the Conceivability Principle – untenable: the conceivability of the zombie hypothesis does not entail its 1-possibility because the range of possibilities is constrained by the powers which are instantiated in the actual world. Since the properties which actually produce P in the world also determine the truth of Q (since the actual world is not a dualist world) and do so as a matter of necessity, there is no possible situation in which P & ¬Q is true.Footnote 23

The ontology of pure powers under consideration also offers an actualist account of modality. If one has a naturalist or Aristotelian conception of powers, only the powers which are actually instantiated existFootnote 24 and those powers which do exist determine the range of possibilities which there are, thereby also blocking the conceivability argument by ruling out the possibility of the zombie hypothesis.Footnote 25 However, one might be sympathetic to such naturalist actualism and yet think that the move which collapses all possibilities and necessities into those determined by actually existing powers is implausible. In particular, one might consider it implausible to account for necessary truths and falsehoods, such as mathematical, logical or analytic propositions, using powers instantiated in the actual world (Yates, 2015). If one gives an alternative account of the necessity of these truths which is not based on powers, a distinction between metaphysical and nomological necessity would remain. So how does this weaker version of dispositional actualism fare when faced with the conceivability argument? Since the possibilities of zombies or zombie worlds are based on the range of possibilities determined by physical causal powers, this variant of actualism will not be relevantly different from the stronger form which treats all possibilities as being determined by powers; zombies and zombie worlds would still not be 1-possible and premise 2 would be false. The actualist powers response to the conceivability argument would stand.

There are some interesting difficulties to be resolved by this actualist account of modality based on powers which might count against its adoption and which its supporters have attempted to allay (Borghini & Williams, 2008; Vetter, 2015; Yates, 2015; Allen, 2017). The main problem concerns its material adequacy; that is, whether such an ontology unduly restricts the range of what is possible. Is it really reasonable to say that everything which is possible is possible in virtue of some actually existing power (which, it is worth noting, need not have been manifested)? In particular, this actualism rules out the existence of truthmakers for counterlegal possibilities, although there have been attempts to mitigate or dilute this result, and for some this counts as an unacceptable restriction. However, these counterlegal possibilities are precisely those which Chalmers uses to keep the conceivability argument in play given the necessary connections between properties grounded by causal powers. Thus in this context, the impossibility of worlds in which the actual laws of nature are false is an advantage, since it allows us to deny the Conceivability Principle of premise 2 which asserts the link between conceivability and 1-possibility: there are not as many possible worlds as we are able to conceive.

Chalmers is dismissive of views which accept this restriction on which worlds are possible (2010, p. 170; 2010, p. 177), although it is a prima facie viable position with an increasing number of supporters. He says the following about theories such as actualist powers theories which involve metaphysically necessary laws:

I think there are no good reasons to accept this extremely strong view of laws of nature and there are good reasons to reject it. The best reasons to take seriously the hypothesis that laws of nature are necessary come from the Kripke and Shoemaker models just mentioned. But nothing in these models supports the strong view or yields a strong necessity. Rather, the CP [conceivability implies 1-possibility] thesis can itself be taken as reason to reject the view. (2010, p. 177)

Elsewhere, he also gives two more related theses underpinning his account: the strong core thesis which links apriority, modality and semantics such that ‘for any sentence S, S is a priori iff S has a necessary 1-intension’ (2004, p. 165) and ‘the thesis of metaphysical plenitude: that every negatively conceivable statement is verified by some centered world’ (2010, p. 170, italics mine). Given the research which has been done recently on modality and laws based on powers, one could dispute Chalmers’ claim that the best reasons to take strong necessities seriously are to be found in Kripke and Shoemaker, although the latter’s account of properties is an antecedent of the ones discussed above. However, since much of this research is later than Chalmers’ 2010, I shall not pursue this line of argument except to note that his comment has become outdated. What stands out in his reasoning here is that Chalmers’ primary argument against theories which involve strong necessities is that they are inconsistent with the Conceivability Principle, a principle which is both needed for the conceivability argument and important in his preferred characterisation of the relationship between rationality, modality and semantics.

Given that there are good reasons for endorsing powers theories and also good reasons for endorsing actualism which are independent of the conceivability argument,Footnote 26 it seems that Chalmers does not have an argument against the actualist powers theorist except for the fact that there is a clash between the actualist’s philosophical position and his own modal rationalism: both are defensible philosophical systems, but they are inconsistent with each other. Against Chalmers, the powers theorist could accept the falsehood of the Conceivability Principle and the loss of plenitude as acceptable consequences, or even advantages, of her philosophical worldview.Footnote 27 At present, a philosophical stalemate has been reached. Since the Conceivability Principle does not hold given an actualist ontology of powers, the conceivability argument does not apply given that ontology and the conclusion that physicalism is false would not be reached.

5 Pure powers and alien properties

In section 5, I will be exclusively concerned with naturalist or Aristotelian accounts of powers as immanent universals or tropes. I will consider Platonic accounts of powers as transcendent universals in the next section.

5.1 Alien properties and the zombie hypothesis

What if one does not want to accept the actualist account of modality, or to align metaphysical and physical possibility in some other way?Footnote 29 Chalmers uses two-dimensional semantics to argue that the powers theory which results will be susceptible to the conceivability argument despite causal laws between powers being necessary. For instance, although Coulomb’s law necessitates that like charges repel, we can conceive of a situation in which like charges attract. Using the reasoning of the previous section, one would presume that conceivability did not entail 1-possibility in this case because it is impossible for charge to have different causal powers from those it actually has. However, if we abandon the restriction to actually instantiated powers, the statement ‘Like charges attract’ is 1-possible: there is a possible world in which it is verified, a world in which there is a property like charge – an old philosophy favourite, schmarge (say) – except for the fact that like schmarges attract rather than repel. Such a world would verify ‘Like charges attract’ and so this statement is 1-possible. Chalmers also accepts (2010, p. 170) that every scenario verifying a 1-possibility corresponds to a centred world, in this case a world with schmarge in it rather than charge; and adds that it is this world we are conceiving of when we conceive of like charges attracting.Footnote 30 So the link between conceivability and metaphysical possibility (2-possibility) is retained (2010, pp. 146–7), except that one is really conceiving of the schmarge world when one conceives of like charges attracting. Thus Chalmers concludes that the conceivability argument still holds in an ontology of powers.

Thus if there are worlds with alien properties which behave in ways that actual powers do not, then these will verify statements denying that actual powers have the effects which they do. While there is no world which satisfies P & ¬Q, so it cannot be 2-possible, there is a world (w* say) which verifies P & ¬Q; in w*, there is a different set of physical properties which can be instantiated while Q is false and which satisfy an alternative sentence P* & ¬Q. This, according to Chalmers, maintains the link between conceivability and metaphysical possibility. In some sense, it is the world satisfying P* which we are thinking about when we are conceiving of the possibility that P & ¬Q; if we supposed that our world is qualitatively like w*, it would rational to accept the possibility of P & ¬Q. (This reasoning holds because according to 2 dimensional semantics, we would mean ‘P*’ by ‘P’ were our world to be qualitatively like one which contains the properties which satisfy P*.)

I think that there are several significant problems with this account of how conceivability affects powers theories which accept that some propositions are physically impossible (at least in terms of the physical properties of the actual world) and yet metaphysically possible.

5.2 What are alien worlds like?

The first difficulty arises from the fact that we only have zombies when we have alien powers. The conceivability argument works in these cases by relying on zombie worlds being worlds which contain causal powers, and hence relations between powers, which do not exist in the actual world. Given this, there is a disanalogy between this application of the conceivability argument and the way in which it is applied to non-dispositional properties.Footnote 31 In most non-dispositional cases, it is the very same properties of the actual world which satisfy the possibility that P & ¬Q in a zombie world, but in the case of powers theories, the properties which satisfy the zombie hypothesis (P & ¬Q) are alien. However, even if we accept that there are worlds with alien properties, it is not clear that they can do the work which Chalmers expects of them. There are two interrelated questions to consider: Are the requisite alien worlds compatible with the claim that all properties are powers? And, is there an alien world which can be used to ground the zombie hypothesis in such a way that the conceivability argument presents a genuine worry? The questions are related because a negative answer to the first question will entail a negative answer to the second; but there may also be reasons to argue that an alien world in which properties are essentially powerful does not satisfy the zombie hypothesis either.

What is it like in worlds which verify the negation of natural necessities involving powers? One might think that this depends upon which natural necessity is being negated: local claims such as ‘Like charges repel’ or ‘Water = H20’; or the more global P → Q (the denial of which gives us the zombie hypothesis P & ¬Q), where the combined causal powers of all physical properties might be at issue. However, the possibility of P & ¬Q might also be grounded in local changes to the causal powers of very few physical properties, in which case this example will be covered by discussion of the local cases. Furthermore, it seems that the global case is quite clear cut. If the negation of a natural necessity can only occur in a world w** in which there is a global, or extremely widespread, change in the causal powers of properties from those of the actual world, there would be good reason to question whether w** is sufficiently like the actual world. Recall that pure powers are identified and individuated on the basis of their causal powers and so the properties of w** would be entirely or largely distinct from those of the actual world. The zombie hypothesis does not seem to be a genuine worry for physicalism if it has to be cashed out as ‘In a world containing completely different physical properties from the actual world, the phenomenal properties might be different’. For this reason I will concentrate upon cases where the denial of a natural necessity appears to involve local change and deal with residual worries about the current point in 4.2.3.

5.2.1 Holism, or a change of categories?

Let us consider the schmarge worlds, where like schmarged particles (and other like schmarged entities) attract and it is false that ‘Like charges repel’. Given that schmarge is a power which causally relates to other powers as a matter of necessity, a schmarge world will not simply be a world just like this one where the only difference is that schmarge exists, and like schmarged entities attract and unlike ones repel. It cannot, in other words, be construed along the same lines as the Twin Earth examples in which everything is qualitatively the same as the actual world except for the molecular structure of the watery stuff which falls from the sky and fills rivers and lakes. Schmarge, if truly a power, will be identified and individuated by its causal role and the difference between schmarge and charge will result in differences in the ways in which it relates to other physical properties. Since electric charge is related to properties such as charge density, electric field, electric current, magnetic field, magnetic density, and via these to all properties related to electromagnetism including those concerning light, heat, and matter, we might presume that schmarge will be related to a similarly large number of properties. Given that these properties are also identified and individuated by their causal roles, this difference matters to the identities of the other properties in the schmarge world too: they are also alien properties (or at least some of them are).

There might be a limit on the differences between the worlds if a set of properties can be causally isolated with respect to differences in their causal role, such that a set of properties could be ‘removed’ from or replaced in a world without affecting the others, either causally or through synchronic determination relations such as supervenience if these exist. If so, the existence of schmarge in a world might not entail that every property in that world is distinct from the properties in this one. However, given that schmarge (and charge) is such a fundamental property, and we are discussing the fortunes of physicalism, it certainly seems plausible to worry that a shift from charge to schmarge could result in all the other properties of the world being alien too.

The upshot of this holism is that worlds which contain alien powers are thoroughly different from the actual world and so it is not clear that we should accept Chalmers’ insistence that such worlds are a genuine worry if they contain zombies. A schmarge world which verifies the claim that ‘Like charges attract’ and thereby renders it 1-possible is so utterly different from a charge world that it makes it difficult to see why such a world should be in some sense what we are thinking about when we consider like charges attracting.Footnote 32 Certainly, Chalmers is right to say that if we thought the world were relevantly like a schmarge world, we would have good reason to believe that ‘like charges attract’Footnote 33 but what reason could we have to worry that the actual world could be ‘qualitatively’ (or, in this case, powerfully) like a schmarge world when such a world is completely different from the actual one? It doesn’t seem to be a relevant worry to have: if the actual world had completely different properties and therefore laws, like charged particles would attract. Likewise with the intuitions about the possibility of zombies: should we be concerned that if the actual world contained completely different entities from the ones it actually contains, then the phenomenal properties of the world could be different or absent? I’m not convinced that this a genuine concern for physicalists and I don’t think that powers theorists who accept alien properties should be either, although I will strengthen this response in 4.2.3.

If one is a powers theorist, I think that similar observations about holism apply to the Twin Earth examples: we cannot just switch one powerful property for another and keep the rest of the world qualitatively the same. A world which contains XYZ rather than H20 is going to be radically different in many other ways from Earth, unless the holistic, knock-on effect of swapping one power for another with different causal relations can be contained. This is relevant to the powers theorist because Chalmers’ use of the Kripkean a posteriori necessities to make his case relies upon contingentism about causal powers; the plausibility of saying that XYZ is really what we are conceiving of in thinking that a posteriori necessities are false (and that the existence of such worlds somehow justifies the link between conceivability and possibility) relies upon those worlds being pretty much the same as the actual one or else they are just not relevantly similar. (See Chalmers, 2010, Chapter 6, especially p. 147.)

Given this holism associated with powers, one might be concerned that the worlds which verify the zombie hypothesis are not ones which contain powers but ones containing categorical properties, properties which have their causal roles contingently. In traditional discussions of a posteriori necessities, the difference between an H20 world and an XYZ world is just the difference in the chemical structure of water with no attention paid to the effect that this change would have on the structure of everything else in the world. H20 and XYZ can only be swapped in this way if they (and other properties with which they are in causal contact) have their causal roles contingently. For a powers theorist, this is impossible because such properties do not exist: the qualitative nature of such a world must consist in something else. For instance, the entities which fix the qualitative nature of worlds where one actual property is swapped for an alien one could be called schmoperties (to borrow a term from Aranyosi (2010, p. 65) who raises a similar objection). The powers theorist then faces a metametaphysical choice between saying that there are such schmoperty worlds but that their existence does not ground possibilities relevant to the conceivability argument, or that they do not exist at all. If one accepts a version of the thesis that basic ontological categories exist necessarily if they exist at all, the latter is the more plausible option: if one is a powers theorist, then properties are powers in every possible world in which they exist (see, for example, Allen, 2015). If one wants to leave space for some possibilities in which ontology is different, one might permit the existence of schmoperties, but the existence of worlds containing these would not be grounds for genuine worries about the possibility of zombies. ‘If the ontological categories of the actual world were different, then physical properties might not produce phenomenal ones’ is not a threat to physicalism at all.

5.2.2 Powers without holism?

Perhaps the case for holistic causal relations between powers is not so clear cut, so in order to cover the different ways in which a powers world could be, let us now consider a slightly different account of powers which is not tied into holism. (This is important since I have only sketched reasons why holism is likely to be true.) On this account, it is possible for a schmarge world to be like a charge world except that the causal interactions which schmarge enters into differ from those of charge in specific ways. (I don’t think that this will avoid there being ‘knock-on’ effects with other properties, but let us pretend that these are minimal. Thus, such worlds are not completely alien because, as well as schmarge, they contain properties which are instantiated in the actual world.) It is still, I think, contentious to follow Chalmers’ line of reasoning and say that the conceivability of such possible worlds should cause genuine worries about the metaphysical possibility that charge could be different from how it actually is: the relevant properties involved in the difference—charge and schmarge—are distinct powers and furthermore, it is not obvious that there is enough shared content to them to maintain that they share a common primary intension.

Taking the zombie hypothesis P & ¬Q, an analogous situation would occur: P* worlds verify P & ¬Q and whichever physical properties make it the case that P* are different from those which make it true that P because some or all of them fail to cause (or otherwise determine) phenomenal properties and the identity of powers consists in their causal role. So why should P* worlds give us cause for concern about the possibility of zombies? In the case of the zombie hypothesis (in comparison with the schmarge one), there might be more to this scepticism because P and P* by definition are epistemically speaking the ‘same’ world from a physical point of view, whereas the schmarge world would be locally epistemically distinct (and might be different elsewhere too).Footnote 34 But given that we are allowed to assume that the actual world is the world in which P and nothing else brings about Q, it is hard to see what the problem is, since there is a phenomenal difference between the worlds: the properties in the world which determine the truth of P and hence Q are different from those which determine the truth of P*; the fact that the actual world could have been a world in which there were different physical properties and these did not determine phenomenal ones (or where there were physical properties and no phenomenal ones) does not seem sufficient to ground worries about zombies concerning the causal powers of the actual world.

5.2.3 Residual doubts about alien worlds

One might find these responses implausible, in both the holistic and non-holistic cases, on the grounds that we should still be worried about zombies even if the zombie hypothesis is only ever satisfied in a world containing alien properties.Footnote 35 A world with alien powers, the objector might suggest, could be structurally isomorphic to the actual one with respect to its physical powers, such that a world w′ in which P′ & ¬Q is true is alien but not dissimilar to the actual P & Q world in physical respects. Such a result would show that phenomenal facts Q are in some sense separable from our physical theory and would raise concerns about whether any powers-based functionalist account of consciousness might be similarly separable in this sense from the physics we have. I think that the powers theorist should resist this line of thinking, however. The most important reason for this is that if she takes this concern seriously, then the worry will generalise to concerns that the powers postulated by any part of our physical or psychological theory are separable from any other part in the same way that phenomenal powers appear to be separable from physical ones. For instance, it is conceivable that the powers associated with the theories of electricity and magnetism could be separated even though they cannot be as a matter of natural necessity (given what we know about electromagnetism in current physics). For example, I can conceive of a situation in which moving a copper wire through a magnetic field does not generate a current and, moreover, that in this scenario there are no further differences in effects from the actual world such that this change in powers is entirely compensated for by other powers, including (if this is required for the example) producing the effects of a current manifesting in the wire. As in the examples of P & ¬Q, this situation could only be satisfied by alien powers, albeit similar ones to those in the actual world. (One might be concerned about whether we can tell what similarity between powers amounts to when we are trying to measure powers with different causal or nomic roles against each other. This is an important question but I will accept their similarity in these examples, since their not being suitably similar strengthens my case that the conceivability of these alien powers situations should not lead to a genuine worry about the actual world.) Should the powers theorist be concerned about this situation, bearing in mind that similar alien powers examples could be formulated for any other nomologically necessary connections between actual powers? Answering in the affirmative amounts to accepting something analogous to the zombie hypothesis for every physical or psychological interaction and the consequences of that. On the one hand, that response seems absurd since it would be taking conceivability worries too far, and on the other it introduces parity between physical-physical explanations and physical-phenomenal ones which effectively neutralises the problem of consciousness; phenomenal powers would not be a special case. If the answer is negative, one might ask why the conceivability of the absence of or a difference in phenomenal powers is different to the conceivable physical-physical cases.

One of the reasons that we do think of phenomenal powers as a special case, I would suggest, is that we do not yet have a robust theory of the relationship between physical and phenomenal powers. (Readers with a background in physics will most probably have been hostile to the electricity and magnetism example for precisely the reason that it does such damage to our current understanding of what physical powers do.) Were we to have a better account from neurophysiology and psychology of ways in which broadly-speaking physical powers determine phenomenal ones, then perhaps we would be less inclined to regard causation between physical powers and phenomenal ones as being any different from, or more tenuous than, causation between physical powers. With that, the alien worlds in which P & ¬Q would lose the last vestiges of their appeal as worrisome worlds in which physical powers could be separated from phenomenal ones.

5.3 Can we have P & ¬Q without alien powers?

What if the phenomenal powers Q were causally isolated ones, such that the removal of Q would not have a causal impact on the powers which determine P, nor require the existence of alien powers to verify P & ¬Q? (For example, this might be the case if Q were epiphenomenal with respect to the physical, or were emergent causal powers.) In this case, P & Q would be made true by P and a causally isolated set Q and a zombie world would possible which just contained the very same powers which make P true. (This case is similar to the counterexample which Taylor (2017, p. 1900) presents against the powerful qualities responses in which the phenomenal properties are non-physical dispositions and thus continues the discussion of 2.2.3. The powerful qualities theorist would consider such causally isolated phenomenal powers to be qualitative as well as powerful, while the pure powers theorist would not, but the cases can be considered together since the qualitativity is not doing any explanatory work here.) In this case, physical duplicates would not be dispositional duplicates; and physical duplicates of the world could exist such that P & ¬Q were true.

For this counterexample to fit in with the scenario conceived of by the conceivability argument, the causal isolation of Q must be less than complete: there need to be some constraints on the example in order to ensure that Q is produced by the physical properties P in the world in which P & Q is true. Otherwise, this world is not a minimally physicalist one but one where dualism is true (and that is not a relevant starting point for the conceivability argument). Taylor (2017, p. 1906) considers two ways in which this might occur: the phenomenal properties Q are not produced as a matter of necessity by P, thus there are possible worlds which which they are missing; or, the production of Q is non-causal, such that Q are emergent properties.

However, there are serious difficulties with the plausibility of both these scenarios and so ultimately I think that Taylor’s claim that the conceivability argument remains a problem for powers or powerful qualities theorists is mistaken. On most accounts, powers produce their effects as a matter of necessity as long as whichever other powers are present remains constant, the only way to prevent this production is for there to be other powers which interfere with or mask the production of Q. However, the need for additional powers in the zombie world to thwart or conceal the production of Q is in contravention of the condition that P & ¬Q must be possible in a world which minimally satisfies P, such that P is true and that’s all. If a world where P & ¬Q is satisfied requires the existence of non-physical powers which interfere with or mask the production of Q, then such a world does not minimally satisfy P. Taylor (2017, p. 1907) considers a version of this response that it is illegitimate for a bona fide zombie world to require non-physical interferers and judges it a stalemate. He does not, however, consider Chalmers’ endorsement of Jackson’s constraint that the P & ¬Q world must contain enough to minimally satisfy P and nothing else (1998, p. 26). This, I think, rules out interferers from inclusion in bona fide zombie worlds.

Furthermore, even in those theories where powers do not manifest as a matter of necessity, it is not obvious that Taylor’s counterexample works. For instance, in Mumford and Anjum’s theory (2018), powers produce their effects with a sui generis modality – dispositional modality – which is stronger than contingency and weaker than necessity. Given this, all the powers which satisfy P could be present and Q not occur, a scenario which appears to satisfy the zombie hypothesis. However, such a possibility is not a true zombie case since it is possible in the actual world too: actual P has produced Q but it actually may not do so next time properties P are instantiated; and the same is true for all other causal production by powers, including all physical powers causing other physical powers. The dispositional modality which governs powers would, on this view, be incorporated into our understanding of the physical and so there would be no disanalogy between the production of physical powers and the production of phenomenal ones. The possibility of P & ¬Q facilitated by dispositional modality does not count as a refutation of physicalism.

5.3.1 Emergent phenomenal powers

The second option which Taylor suggests whereby phenomenal powers are produced by physical ones and yet the conceivability argument still applies is if such phenomenal powers were not produced by the causal manifestations of the physical powers but by some other mechanism such as emergence (2017, p. 1907). Although it will be impossible in this paper to consider the range of ways in which emergence could be understood, it is fairly easy to show that Taylor’s suggestion is not particularly promising.Footnote 36 The reason for this is that two main ways in which emergence is characterised involve either supervenient determination (van Cleve, 1990; McLaughlin, 1997) or causal determination of the emergent properties by the base ones (O’Connor, 2000, chapter 6). This would suggest that, contrary to Taylor, the process of emergence could be best understood in terms of the powers of physical properties (with supervenient power being understood as a synchronic form of determination analogous to causation) and therefore that emergence could be understood in terms of the manifestations of powers after all. Furthermore, this determination occurs as a matter of nomological necessity such that the presence of the same physical powers necessitates the same emergent ones, and so which phenomenal properties emerge from a specific physical power or powers would remain the same in different possible situations.Footnote 37 The difficulty which Taylor faces here is that the difference between the supervenience and causation involved in emergence and other cases of supervenience and causation does not consist in a difference in the mechanism involved to bring about the phenomenal properties but rather the fact that emergence brings about ontologically novel properties with novel causal powers, while ordinary supervenience and causation do not. The difference between emergent and non-emergent production lies in the entities produced, not in the mechanism used to produce them which would be the same in both cases, so that claiming that phenomenal properties could be produced by emergence makes no difference to whether non-actualist powers theories are susceptible to the conceivability argument.

It is not obvious whether this observation about the nomological necessity of the emergence relation extends to every way in which one could understand emergence. Perhaps if we understand the emergence of phenomenal powers as being in virtue of the fusion of physical powers, then the production of Q by P is not even analogous to causation between powers and the conclusions of the previous paragraph can be avoided (for example, Humphreys, 1996, 1997). However, even in this case it is not obvious that specific collections of properties do not necessitate specific emergent ones. If emergence from powerful properties is to provide a counterexample to the pure powers responses to the conceivability argument, then such production will have to be contingent, brute production of phenomenal properties by physical ones. Moreover, such production will also always have to occur in the actual world whenever the requisite powers are instantiated, or else the production failure of a zombie world will not be remarkable or cause for concern. If production of Q by P is not assured by every instantiation of P in the actual world, then the same story can be told about this as about production of Q by dispositional modality or by indeterministic processes. The fact that Q might not actually occur given P is unremarkable; what is needed to make a zombie world a counterexample to physicalism is that Q never occur in the zombie world and furthermore that Q could not occur in that world on the basis of P, and this would require alien powers. (The latter modal constraint is to rule out the accidental zombie scenario that Q happens never to occur in a world when P does, although it could do.)

What is required if these are to be genuine counterexamples to the powers theorists’ responses to the conceivability argument is that in some respect powers behave like purely qualitative or categorical properties (which have their causal roles and other ‘productive’ roles contingently) when phenomenal powers are produced. Although I cannot rule this option out a priori, such emergence is both a fairly implausible and unlikely view about the way that powers behave. Moreover, this understanding of powers theory is even less plausible once we consider that the nature of pure powers is exhausted by their causal roles, so that any contingent part they play in the production of Q could not be in virtue of their nature.

The situation might seem a little more plausible in the case of powerful qualities since perhaps they could fuse in virtue of their qualitativity. One might be perplexed about how the qualitative intrinsic natures of powers could fuse to create novel emergent powers but I will leave that concern aside for now as there are greater worries with this suggestion. In particular, as I noted in 2.2, the qualitativity of powerful qualities is never more fine-grained than their causal power (and is often regarded as identical to it), so distinct qualities are never associated with a single power. Thus, there could be no qualitative difference between the powerful qualities which satisfy P in the actual world (and produce Q emergently by fusion) and the powerful qualities which satisfy P & ¬Q in the zombie world (since these are, by hypothesis in this example, the same powers). So we are left with a mystery about why qualitative fusion to produce emergent phenomenal powers (which satisfy Q) always occurs in the actual world but never in the zombie world, and why the role played by qualities in emergent fusion is contingent while the causal powers of the very same entities are necessary. (This would not, for instance, work if qualitativity and powerfulness are identified.) Even if we can make sense of the relationship the qualitativity and powerfulness of powerful qualities in such a way that emergent fusion turns out to be contingent, we need some good independent reasons to think that this is how powerful qualities behave. Without this, the acceptance of this ontology is question-begging since it seems entirely motivated by the desire to make physicalism a contingent doctrine and to provide an ontology in which the conceivability argument applies (and thereby disprove physicalism).

5.4 Pure powers and alien properties: A summary

Above I have argued that even if the holistic interconnections between powers can be restricted, there is very little chance that the conceivability argument will apply in an ontology of pure powers, since it is implausible to think that we are really thinking of worlds containing alien powers when we worry about the possibility of zombies. Unless we postulate the existence of some form of emergent productive mechanism akin to that which is usually associated with categorical properties, the conceivability argument does not apply in an ontology of pure powers, even when one accepts the existence of alien properties. The worry about the existence of zombies in all cases amounts to saying that if the world had different properties in it, or different ontological categories, then things would be different (perhaps there would be schmarge, perhaps there would be zombies). It is not obvious why the physicalist should take this concern seriously. Thus, even if we eschew the idea that powers theory entails holism, I don’t think that conceivability is a genuine worry in a world of powers.