Abstract

This historiographical study aims at introducing the category of “situated mathematics” to the case of Ancient Egypt. However, unlike Situated Learning Theory (Lave, 1988; Greeno et al., 1993), which is based on ethnographic relativity, in this paper, the goal is to analyze a mathematical craft knowledge based on concrete particulars and case studies, which is ubiquitous in all human activity, and which even covers, as a specific case, the Hellenistic style, where theoretical constructs do not stand apart from practice, but instead remain grounded in it.

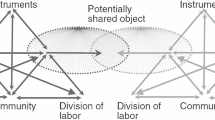

The historiographic interpretation that we will give of situated mathematics is inscribed in a characterization of mathematical styles that focuses on the role of mathematical practice (Visokolskis, 2020; Visokolskis & Trillini, 2020). This categorization describes three types of mathematization, where, on the one hand, type I represents the classical and dominant Hellenocentric approach, which seeks to generate a body of principles that could then be applied in other fields. On the other hand, types II and III represent two kinds of situated mathematics, a parametrized and a concrete one. Type II proceeds in the opposite direction from Type I describing an application of a previously obtained theory. That is, given a practice in any domain, it seeks to build a mathematical systematization a posteriori to explain said practice. Finally, type III starts from a concrete practice and develops another similar practice that explains analogically the relationship.

Based on the typology adopted, we seek to describe a case study within ancient Egyptian mathematics, which reveals how it is possible to subsume it in the two types of situated mathematization II and III. The foregoing will allow to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For further details, see Charette (2012).

The italics are ours.

According to Walter F. Reineke (1977), in LÄ III, cols. 1238-1239, we can mention the following sources: Rhind papyrus (BM 10057 and 10058), Moscow papyrus (GMII Moscow 4676), Berlin papyrus 6619, Kahûn papyrus, the Leather scroll (BM 10250) and Anastasi I papyrus (BM 10247), for mention the most renowned.

The dimensions of the Papyrus are as follows: for BM 10057, length = 319 cm and width = 34.30 cm; for BM 10058, length = 199.50 cm; width = 32 cm.

We use the chronological references exposed in Hornung et al. (2006, pp. 490-495).

This information is in the opening section of the papyrus. Following the analysis of Anthony Spalinger (1990), this section, called “the title”, begins written in red ink and then in black ink, with an arrangement of three parallel and vertical columns that must be read from right to left; such an arrangement was abandoned for hieratic documents after the 12th dynasty. As can be read in the papyrus, the exact date of its writing is the year 33 of the reign of Apophis I.

The italics are ours.

The English translation is ours. This positioning can be traced to more recent times, for example in Imhausen (2016). This author, years ago, expressed herself in similar terms to Reineke: “Traditional approaches to Egyptian mathematics have provided only a superficial account of mathematical practices and almost no information about the role of mathematics within Egyptian culture. (...) In addition, it is indispensable to contextualize the mathematical problems with sources that are not specifically mathematical per se” (Imhausen, 2003a, p. 365). An example of this type of historiographic interpretation based on the contextualization of mathematical sources with other extra-mathematical sources is Imhausen (2003c).

The English translation is ours.

Such is the case of the proposal of an anarchist epistemology by Paul Feyerabend (1987).

The English translation is ours.

The English translation is ours.

For further details, see (Visokolskis & Trillini, 2020, pp. 209-210).

Although the dominant tendency of the interpretations of the Republic agrees with the point of view ut supra posed, some perspectives are offered that contemplate the possibility of certain empirical apparatus allowed in the works of Plato. In this regard, confront with (Gregory, 2001).

Aristotle, An. Post. B 13 79a14-16.

The italics are ours.

It should be noted, at this point, that this procedure for evaluating a formula for given arguments become, for traditional historiographic interpretations, a kind of paradigm of applied arithmetical for ancient Egyptian “geometric” problems. However, we are not pointing out that this is how the sense of “application” should be considered for all applied mathematics in general.

From a linguistic point of view, we can make a significant allusion to this. The temporality mark of the algorithmic sequence is usually introduced using a specific verb form. This corresponds to what James Allen (2014, pp. 295ff.) calls the verb form of a biliterate suffix (or infix) sḏm.ḫr=f, and which is usually translated in the future tense, at least for mathematical papyri. For example, an ancient scribe did not write the operation 1/9 ⋅ 9 =1, but the verb phrase: jrj.ḫr=k r-9 n 9 ḫpr 1, “you will make 1/9 of 9, which will become 1”.

From now on, we will refer to “problem number X” of the Rhind mathematical papyrus by the abbreviation pRhind X.

The ancient Egyptian term tp has been translated in two different senses: as “example” (Chace et al., 1929, plate 72), or as “method” (Peet 1923, p. 90; Imhausen 2003b, p. 249). On the other hand, Wb V, 267.9 points out that underlying tp is the idea that it indicates what to do, i.e., it emphasizes the procedure or methodological steps (Erman & Grapow, 1971, vol. 5, p. 267). We consider that this meaning is more evident in “method” than in “example”, which is why it has been used in the translation of pRhind 50 offered here.

In the columns of transliteration and translation, the bold words correspond to what is written in red ink in the original hieratic text. This writing convention, of starting problems with red ink, is maintained throughout the entire Rhind papyrus, except for those problems that lack a statement such as pRhind 48.

According to Wb V, 437.3 (Erman & Grapow, 1971 vol. 5, p. 437), dbn is classified as circle, like a circle land. However, various translation options can be tracked; for instance: “field round” (Chace et al., 1929, plate 72), “circular piece of land” (Peet, 1923, p. 90) or “round surface (runden Fläche)” (Imhausen, 2003b, p. 249). Here we have chosen “circular area”, since it includes the previous ones, taking into account that, in the ancient scribe’s sense, it is probable that he has thought of the circular surface of a cultivable land.

This translation of ptj rḫ.t=f is derived from the more literal one: “What is the amount of its in area?” (Chace et al., 1929, plate 72), since according to Wb II, 448.19, rḫ.t can be translated as “number (Zahl)” or “amount (Betrag)” (Erman & Grapow, 1971, vol. 2, p. 448). This differs from Peet’s translation: “What is its area in land?” (Peet, 1923, p. 90) who, following what was explained in the previous footnote, considers dbn as a circular piece of land.

The ancient Egyptian words ḫt (khet) and sṯɜ.t (setjat) refer to two units of measurements: the first for lengths and the second for areas. 1 khet is equivalent to 54.2 meters; 1 setjat is equivalent to the area of a square with a side 1 khet, i.e. is equal to 2734.2441 square meters.

In lines 6-7 the multiplication 1/9 ⋅ 9 is solved; in lines 9-12 the multiplication 8 ⋅ 8 is solved.

According to Gómez and Carlos (2009, p. 125) the only testimony about a circular field is pRhind 50, but this should not lead to suppose that they were almost non-existent, since its plotting did not represent great difficulties: a stake was stuck in what would be the center and, tying a rope in it, the circle was demarcated with the other end, keeping it always well stretched. In addition, the circular surfaces arise more frequently in the resolution of the volume of cylindrical granaries, for which the determination of the area of the base was first required.

The elaboration of all hieroglyphic expressions in this paper are ours, and they have been made using the JSesh software. This is an open-source hieroglyphic editor, a word processor for ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts.

The divergent interpretations come from the fact that the Moscow papyrus presents, in that problem 10, a damage in the part of an Egyptian word that is of special importance for the reading of the hieratic text. Indeed, the problem in question deals with the calculation of the area of a three-dimensional body called

nb.t. In its line 6, it is clarified that it is half of another geometric body with no identifiable name, since there is the material damage in the papyrus. For more information, see (Gerván, 2015, p. 9).

nb.t. In its line 6, it is clarified that it is half of another geometric body with no identifiable name, since there is the material damage in the papyrus. For more information, see (Gerván, 2015, p. 9).From now on, the expression \(\overline{n}\). refers to the unit fraction 1/n.

In many unfinished monuments, from the Middle Kingdom (1980-1760 BC) onwards, there are vestiges of the grids used to draw the scenes on the walls. For some studies of ancient Egyptian grids and their relations with geometry and mathematical proportions, see Robins (1994) and Hahn (2017, pp. 12-25).

All images in this Table are ours.

For more information, see (Gerván, 2019).

The English translation, from the original Spanish text, is ours.

References

Allen, J. (2014). Middle egyptian. An introduction to the language and culture of hieroglyphs (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Barnes, B. (1977). Interests and the growth of knowledge. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Bloor, D. (1991). Knowledge and social imagery. The University of Chicago Press.

Boyer, C. (2011). The history of mathematics (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Cajori, F. (1991). A history of mathematics (5th ed.). American Mathematical Society Chelsea Publishing.

Cantor, M. (1894). Vorlesungen uber geschichte der mathematik, vol. i, Von den altesten Zeiten bis zum Jahre 1200 n. Chr (2nd ed.). Teubner.

Caratini, R. (2004). Los matemáticos de Babilonia. Edicions Bellaterra.

Chace, A. B., Manning, H. P., & Archibald, R. C. (1929). The rhind mathematical papyrus vol. II: Photographs, transcription, transliteration, literal translation. Mathematical Association of America.

Charette, F. (2012). The logical Greek versus the imaginative oriental: On the historiography of ‘non-western’ mathematics during the period 1820–1920. In K. Chemla (Ed.), The history of mathematical proof in ancient traditions (pp. 274–293). Cambridge University Press.

Chemla, K. (2003). Generality above abstraction: The general expressed in terms of the paradigmatic in mathematics in ancient China. Science in Context, 16(3), 413–458.

Chemla, K. (2017). Changing mathematical cultures, conceptual history, and the circulation of knowledge. In K. Chemla & E. F. Keller (Eds.), A case study based on mathematical sources from ancient China. In cultures without culturalism. The making of scientific knowledge (pp. 352–398). Duke University Press.

Cooper, L. (2011). Did Egyptian scribes have an algorithm means for determining the circumference of a circle? Historia Mathematica, 38(4), 455–484.

Crombie, A. C. (1994). Styles of scientific thinking in the European tradition: The history of argument and explanation especially in the mathematical and biomedical sciences and arts, 3 vols. Duckworth.

Dawson, W. (1924). Ancient egyptian mathematics. Progress in the Twentieth Century, 19(73), 50–59.

Young, D., & Gregg. (2009). Diagrams in ancient egyptian geometry, survey and assessment. Historia Mathematica, 36(4), 321–373.

Dorce, C. (2018). The exact computation of the decompositions of the recto table of the rhind mathematical papyrus. History Research, 6(2), 33–49.

Eisenlohr, A. A. (1877). Ein mathematisches Handbuch der alten Ägypten, übersetzt und erklärt. Hinrichs.

Epple, M., Hoff Kjeldsen, T., & Siegmund-Schultze R. (2013). From ‘mixed’ to ‘applied’ mathematics: Tracing an important dimension of mathematics and its history. Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach, Annual Report, 12, 657–660.

Erman, A., & Grapow, H. (1971). Wörterbuch der Ägyptischen Sprache (5 volumes.). Akademie-Verlag.

Feyerabend, P. (1987). Against method. Verso.

Gairín Sallán, J. M. (2001). Una interpretación de las fracciones egipcias desde el recto del papiro rhind. Llull, 24, 649–684.

García, M., & Carlos, J. (2017). Trade and power in ancient Egypt: Middle Egypt in the late third/early second millennium BC. Journal of Archaeological Research, 25(2), 87–132.

Gandz, S. (1940). Studies in Babylonian mathematics II. Conflicting interpretations in Babylonian mathematics. Isis, 3(2), 405–425.

Gandz, S. (1948). Studies in Babylonian mathematics I. Indeterminate analysis in Babylonian mathematics. Osiris, 8, 12–40.

Gerdes, P. (2007). Etnomatemática. Reflexões sobre matemática e diversidade cultural. Edições Húmus.

Gervan, H. (2013). Las fracciones unitarias en la matematica Del Antiguo Egipto. In H. Severgnini, J. Gustavo Morales, & D. L. Rabinovich (Eds.), Epistemologia e historia de la ciencia. seleccion de trabajos de las XXIII jornadas (Vol. 19, pp. 165–175). Facultad de Filosofia y Humanidades de la Universidad Nacional de Cordoba.

Gerván, H. (2015). La práctica matemática en el Antiguo Egipto. Una relectura del problema 10 del papiro matemático de Moscú. Anuario de la Escuela de Historia Virtual, 6(7), 1–17.

Gerván, H. (2019). ¿Geometría o agrimensura? Defendiendo la existencia de un conocimiento geométrico en el antiguo egipto a partir del papiro rhind. Communication presented at XX Jornadas Rolando Chuaqui Kettlun “Filosofía y Ciencias”.

Gillings, R. (1972). Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs. Dover Publications, Inc.

Greeno, J., Moore, J., & Smith, D. (1993). The institute for research on learning. Transfer of situated learning. In D. Detterman & R. Sternberg (Eds.), Transfer on trial: Intelligence, cognition and instruction (pp. 99–167). Ablex Publications.

Gregory, A. (2001). Plato’s philosophy of science. Bloomsbury.

Günther, S. (1908). Geschichte der mathematik (Vol. 1, Von den ältesten Zeiten bis Cartesius). Göschen.

Hahn, R. (2017). The metaphysics of pythagorean theorem. thales, pythagoras, engineering, diagrams, and the construction of the cosmos out of right triangles. State University of New York Press.

Hankel, H. (1874). Zur Geschichte der mathematik im alterthum und mittelalter. Teubner.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599.

Hart, R. (1999). Beyond science and civilization: A post-needham critique. East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine, 16, 88–114.

Heath, T. (1998). Mathematics in Aristotle. Thoemmes Press.

Hornung, E., Krauss, R., & Warburton, D. (2006). Ancient Egyptian chronology. Brill.

Imhausen, A. (2003a). Egyptian mathematical texts and their contexts. Science in Context, 16(3), 367–389.

Imhausen, A. (2003b). Ägyptische algorithmen. Eine untersuchung zu den mittelägyptischen mathematischen aufgabentexten. Harrassowitz Verlag.

Imhausen, A. (2003c). Calculating the daily bread: Rations in theory and practice. Historia Mathematica, 30(1), 3–16.

Imhausen, A. (2016). Mathematics in ancient Egypt. A contextual history. Princeton University Press.

Joseph, G. G. (2011). The crest of the peacock: The non-European roots of mathematics (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press.

Karpinski, L. (1917). Algebraical developments among the Egyptians and Babylonians. The American Mathematical Montly, 24(6), 257–265.

Katary, S. (2011). Taxation (until the end of the third intermediate period). In E. Frood, & W. Wendrichs (Eds.), UCLA encyclopedia of egyptology. Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002814vq

Kline, M. (1972). Mathematical thought from ancient to modern times (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

Lave, J. (1988). Cognition in practice. mind, mathematics and culture in every day life. Cambridge University Press.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lloyd, G. E. R. (1998). Techniques and dialectic. In J. Gentzler (Ed.), Method in ancient philosophy (pp. 351–376). Clarendon Press.

Maza Gómez, C. (2009). Las matemáticas en el antiguo Egipto, sus raíces económicas. Segunda Edición. Secretariado de publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla.

Montenegro Martínez, M., & Pujol Tarrès, J. (2003). Conocimiento situado: Un forcejeo entre el relativismo construccionista y la necesidad de fundamentar la acción. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 37(2), 295–307.

Moreno Garcia, J. C. (2013). Land donations. In E. Frood & W. Wendrichs (Eds.), UCLA encyclopedia of Egyptology. Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002hgp07

Neugebauer, O. (1957). The exact science in antiquity. Brown University Press.

Palmer Miquel, A. (2007). Interpretación matemática situada de una práctica artesanal [PhD Thesis]. Facultat de Ciènces de l’Educació de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Peet, T. E. (1923). The rhind mathematical papyrus. British museum 10057 and 10058. Introduction, transcription, translation and commentary. The University Press of Liverpool.

Suárez, P., & Emilio, C. (2014). Conocimientos situados y pensamientos fronterizos: Una Relectura Desde La Universidad. Geopolítica(s), 5(1), 11–33.

Plato. (1994). Republic. In H. N. Fowler, W. R. M. Lamb, R. G. Bury, & P. Shorey (Eds.), Plato in twelve volumes (Vol. 6). Harvard University Press.

Reineke, W. (1977). Mathematik. In W. Heck, E. Otto, & cols (Eds.), Lexikon der Ägyptologie, vol. III (pp. 1238–1245). Otto Harrassowitz.

Reineke, W. (1979). Mathematik und Gesellschaft im Alten Ägypten. In W. Reineke (Ed.), Acts of the first international congress of egyptology (pp. 543–552). Akademie-Verlag.

Ritter, J. (1989). Chacun sa vérité: Les mathématiques en Égypte et en Mésopotamie. In M. Serres (Ed.), Éléments d’histoire des sciences (pp. 39–61). Presses Universitaires de France.

Robins, G. (1994). Proportion and style in Egyptian art. University of Texas Press.

Robins, G., & Shute, C. (1990). The rhind mathematical papyrus. An ancient Egyptian text. Dover Publications, Inc..

Sagástegui, D. (2004). Una apuesta por la cultura: El aprendizaje situado. Revista electrónica Sintética, 24, 30–39.

Spalinger, A. (1990). The rhind mathematical papyrus as a historical document. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur, 17, 295–337.

Tannery, P. (1915–1950). Mémoires scientifiques (Vol. 17). Édouard Privat.

Visokolskis, S. (1994). Arquímedes y el descubrimiento matemático: Un caso histórico. In V. Rodríguez & N. Horenstein (Eds.), Actas de las cuartas jornadas de epistemología e historia de la ciencia. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba.

Visokolskis, S. (2009). El fenómeno de la transducción en la matemática. Metáforas, analogías y cognición. In M. Pochulu, R. Abrate, & S. Visokolskis (Eds.), La metáfora en la educación. Descripción e implicaciones (pp. 37–53). Eduvim.

Visokolskis, S. (2020). El papel de la matemática aplicada en la historia y su estatuto epistemológico: Estudio de caso. Communication presented at Primeras Jornadas de Historia de las Matemáticas Suroccidente Colombiano. Santiago de Cali, Colombia.

Visokolskis, S. (2021). Insightful yet inferential creativity: Transduction as a derivation of abduction. In M. O. Galindo, J. R. M. Romero, C. Z. Cortés, & P. Pozos-Parra (Eds.), Proceedings of the thirteenth Latin American workshop on logic/languages, algorithms and new methods of reasoning, CEUR workshop proceedings (pp. 23–38). CEUR-WS.org.

Visokolskis, S., & Trillini, C. (2020). In the quest for invariant structures through graph theory, groups and mechanics: Methodological aspects in the history of applied mathematics. In Y. Sergeyev & D. Kvasov (Eds.), Numerical computations: Theory and algorithms. Third international conference, NUMTA 2019, Crotone, Italy, June 15–21, 2019, Revised selected papers, part II, lecture notes in computer science book series, volume 11974 (pp. 208–222). Springer.

Vogel, K. (1958). Vorgriechische mathematik, Bd. 1: Vorgeschichte Ägypten. Hermann Schroedel und Paderborn.

von Stadent, H. (1992). Affinities and elisions: Helen and Hellenocentrism. Isis, 83(4), 578–595.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Secretary of Research in Science and Technology (SECyT-UNC), and the Research Group of Visualization in Mathematics, National University of Cordoba, Argentina.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

We don’t have conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

We accept.

Informed consent

We accept.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Visokolskis, S., Gerván, H.H. Applied versus situated mathematics in ancient Egypt: bridging the gap between theory and practice. Euro Jnl Phil Sci 12, 12 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-021-00419-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-021-00419-9

nb.t. In its line 6, it is clarified that it is half of another geometric body with no identifiable name, since there is the material damage in the papyrus. For more information, see (Gerván,

nb.t. In its line 6, it is clarified that it is half of another geometric body with no identifiable name, since there is the material damage in the papyrus. For more information, see (Gerván,