Abstract

Cancer survivorship education is limited in residency training. The goal of this pilot curriculum was to teach medicine residents a structured approach to cancer survivorship care. During the 2020–2021 academic year, we held eight 45-min sessions in an ambulatory noon conference series for a community family medicine (FM) and internal medicine (IM) residency program. The curriculum used Project ECHO®, an interactive model of tele-education through Zoom video conferencing, to connect trainees with specialists. Each session had a cancer-specific focus (e.g., breast cancer survivorship) and incorporated a range of core survivorship topics (e.g., surveillance, treatment effects). The session format included a resident case presentation and didactic lecture by an expert discussant. Residents completed pre- and post-curricular surveys to assess for changes in attitude, confidence, practice patterns, and/or knowledge in cancer survivorship care. Of 67 residents, 23/24 FM and 41/43 IM residents participated in the curriculum. Residents attended a mean of 3 sessions. By the end of the curriculum, resident confidence in survivorship topics (surveillance, treatment effects, genetic risk assessment) increased for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers (p < 0.05), and there was a trend toward residents stating they ask patients more often about cancer treatment effects (p = 0.07). Over 90% of residents found various curricular components useful, and over 80% reported that the curriculum would improve their practice of cancer-related testing and treatment-related monitoring. On a 15-question post-curricular knowledge check, the mean correct score was 9.4 (63%). An eight-session curriculum improved resident confidence and perceived ability to provide cancer survivorship care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2019, there were 16.9 million cancer survivors in the USA, with the number of cancer survivors expected to rise to 22.1 million by 2030 [1]. With an expected shortage of oncologists, primary care providers (PCPs) will share more responsibility for the follow-up care of cancer survivors. As the number of patients living with cancer grows, innovative education on the care of this population is critical.

While various cancer survivorship curricula targeting PCPs exist, a recent systematic review of survivorship training and education for PCPs suggests that relatively few programs are based on survivorship frameworks and teaching theories, and the educational outcomes measured in studies were narrow in scope [2]. Furthermore, there has been limited cancer survivorship education during residency for future physicians. In a recent survey, only 9% of family medicine residency program directors reported having a cancer survivorship curriculum [3]. Family medicine (FM) and internal medicine (IM) residents in a separate survey reported low confidence on core cancer survivorship topics (cancer recurrence and long-term effects of cancer treatment), and had low rates of receiving formal survivorship education [4]. While cancer survivorship education for trainees has been limited, the potential for expanding educational opportunities in this learner group is promising. A prior curriculum for 15 hematology/oncology fellows and radiation oncology residents showed the feasibility of a six-session workshop series to provide meaningful survivorship education [5].

By designing this interactive tele-educational pilot curriculum using the Project ECHO® (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model, we aimed to provide residents in a family medicine and internal medicine program with a structured approach for delivering cancer survivorship care, and improve their confidence on survivorship topics.

Methods

Project ECHO®

While ECHO® was originally designed as a model of tele-mentoring to connect specialists (at a hub site) with community providers (at spoke sites) of underserved populations, this model was adapted to educate FM and IM residents. The curricular development team was the hub site, while the two residency programs served as the spoke sites. The hub team included two general internal medicine faculty members with expertise in cancer survivorship, a general internal medicine fellow, and an information technology coordinator. In addition to the participating residents, the spoke teams included one FM faculty associate and two IM assistant program directors. The curriculum followed Project ECHO®’s 4 “ABCD” principles: Amplification (using video conferencing technology, Zoom), sharing Best practices through audience participation under the guidance of experts, Case-based learning with clinical scenarios chosen by participating community providers, and a web-based Database to monitor outcomes including participation. Tele-education also involved using live polling questions during the session to increase participation, as well as the hub team and faculty moderating the chat with questions and responses from residents. Small-group break-out sessions were not used.

Curriculum

The pilot curriculum was designed as part of the Johns Hopkins Longitudinal Program in Curriculum Development after a cancer survivorship curriculum was identified as a need through local stakeholders. Tele-educational sessions were incorporated into an ambulatory noon conference series for two community residency programs. The sessions followed the standardized format encouraged by ECHO®, with a brief introduction followed by a relevant case presentation/discussion (25–30 min) and didactic presentation (10–15 min). A resident volunteer was identified in advance of each session to (1) prepare a case presentation of a cancer survivor based on a standardized template (Supplement A) and (2) identify several clinical questions about the patient to discuss with the other residents and an expert discussant. Based on a discussion among the spoke team faculty and hub team, a PowerPoint case outline replaced the standardized template mid-way through the year to improve the delivery of case presentations.

Sessions had a theme based on cancer type (e.g., breast cancer survivorship) or cancer survivorship topic (e.g., health promotion); other core survivorship topics, including cancer surveillance and late effects of treatment, were woven into each session as appropriate based on the case and clinical questions. The hub team and spoke team faculty selected breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers as recurring session themes, based on the prevalence of these cancers seen in primary care. They also selected health promotion and palliative care as important session themes to cover. The remaining session topics were guided by resident rankings of other survivorship topics within our pre-curricular survey (Table 1).

Session content for the knowledge questions and didactic presentations derived from societal guidelines, including the American Cancer Society, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network, as well as primary literature, UpToDate, and expert opinion from our expert discussants [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

The hub team invited one expert discussant for each session based on the thematic content. The expert discussants were provided with the case in advance of the session to plan their didactic presentation accordingly. One hub team member acted as a facilitator for each session to promote discussion and ask questions. Multiple choice knowledge questions were incorporated into each session via Qualtrics or Zoom poll to engage learners and assess pre-curricular knowledge. The same knowledge questions were repeated at the end of the session to solidify teaching points.

The hub team and spoke team faculty had a monthly phone conference to discuss the prior session, as well as to plan and modify for the next session.

Target Learners

PGY 1–3 residents from one FM and one IM residency program in Reading, PA, participated in the curriculum.

Assessment and Evaluation

Residents completed a pre-curricular survey (Supplement B), which included a targeted needs assessment asking about any prior cancer survivorship education and intended career plan. Additionally, residents were asked to select which survivorship topics would be most helpful to their clinical practice (from a list created by the hub team and spoke team faculty) and to rate the importance of PCP involvement in various components of survivorship care (surveillance for cancer recurrence, late effects of treatment, psychosocial well-being, and preventive care) on a 5-point Likert scale (not important, somewhat important, neutral, important, very important).

The pre- and post-curricular surveys (Supplement B) had identical questions about confidence and practice patterns around survivorship care. Residents were asked about confidence in managing the following components of survivorship for 3 common cancers (breast, colorectal, and prostate) on a 3-point Likert scale (not confident, somewhat confident, very confident): monitoring for disease recurrence, screening for treatment effects, and assessing genetic risk. With the exclusion of PGY-1 for the pre-curricular survey, residents were asked how often they addressed the following with cancer survivors at follow-up visits on a 5-point Likert scale (never, seldom, sometimes, most of the time, every time): depression screening, assessment for case management/social work referral, and asking about cancer treatment effects.

The post-curricular survey included a knowledge check and program evaluation of the curriculum. The 15-question knowledge check drew from knowledge questions used during individual sessions; the selected subset of questions was based on a blueprint of session themes and survivorship topics covered across the sessions (Table 1).

For program evaluation, residents were asked to rate the usefulness of the following curricular components on a 3-point Likert scale (not useful, useful, extremely useful): case presentation, expert discussant’s input on the case, knowledge questions, didactic presentations, and follow-up email with didactic slides and knowledge questions with explanatory answers. Residents were also asked to rate to what extent they agreed with the following statements about the curriculum on a 4-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree): opportunities to ask questions, providing an approach to gather cancer diagnosis and treatment information, monitoring cancer surveillance more appropriately and monitoring for cancer treatment effects more often as a result of the course, curricular resources improving their care of cancer survivors, and recommending this curriculum to other medicine residents. There were final questions regarding whether the following aspects of the curriculum affected participation on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly decreased, decreased, neutral, increased, strongly increased): large-group format, session time, 2 participating residency programs, and facilitation by the hub team.

Attendance, responses to knowledge questions, and survivorship topics were tracked per session. The pre-curricular survey was anonymous but asked for PGY information to analyze data in aggregate. The remaining data (session data and post-curricular survey) were linked to individual residents, but anonymized for analysis. A lottery for two $100 gift cards was provided as an incentive for completion of the post-curricular survey.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses of attendance and pre- and post-curricular survey results were conducted. Chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test, Wilcoxin Mann–Whitney test, and Kruskal–Wallis (with ties) were used as appropriate to look for statistical differences in responses to questions repeated in the pre- and post-curricular surveys (confidence, practice patterns), as well as to evaluate for differences in responses by PGY and residency program (FM vs IM) for survey completion and questions about attitudes, confidence, and practice patterns.

Results

During the 2020–2021 academic year, eight ECHO® sessions were scheduled approximately once a month. Based on resident response, lung cancer survivorship and the care of survivors with hematologic malignancies were included as session themes (Table 1).

There were 24 FM residents (8 PGY-1, 8 PGY-2, 8 PGY-3) and 43 IM residents (19 PGY-1, 12 PGY-2, 12 PGY-3). Of 44 residents completing the survey, nearly three quarters reported primary care (24 residents, 55%), hospital medicine (5 residents, 11%), or a combination of both (3 residents, 7%) as their intended career plan. Five of these residents expressed interest in additional specialties including gastroenterology, palliative care, pulmonary/critical care, rheumatology, and sports medicine. The remaining residents reported interest in emergency medicine, gastroenterology, geriatrics, hematology/oncology, pulmonary/critical care, rheumatology (1 resident, 2% for each respective specialty), and cardiology (3 residents, 7%), with 3 undecided residents (7%).

Attendance

Attendance at each session ranged from 17 to 46 residents, with mean attendance of 26 residents per session. Of 67 total residents, 23/24 FM and 41/43 IM residents participated in at least one session; 1 resident attended all 8 sessions. Residents attended a mean of 3 sessions (SD 1.6). Three PGY-3 residents (1 FM, 2 IM) did not participate in any sessions.

Survey Completion

Of the 67 residents across the two programs, 44 residents (22 FM, 22 IM) completed the pre-curricular survey (67% response rate). PGY was evenly represented (14 PGY-1, 14 PGY-2, 16 PGY-3) and similar across programs (p = 0.74). Of the same 67 total residents, 33 residents (11 FM, 22 IM) completed the post-curricular survey (49% response rate) while an additional 7 residents (2 FM, 5 IM) partially completed the post-curricular survey (all but the knowledge check questions). PGY was evenly represented (14 PGY-1, 10 PGY-2, 9 PGY-3) and similar across programs (p = 1.00).

Targeted Need Assessment/Attitudes About PCPs Managing Survivorship Care

Across all respondents, 87% reported receiving no cancer survivorship education during medical school, and 94% reported none during residency (p = 0.35 and 0.18, respectively). In assessing attitudes about the importance of PCP involvement in various components of survivorship care (surveillance for cancer recurrence, late effects of treatment, psychosocial well-being, and preventive care), 96–100% of residents reported that all of the topics were important or very important.

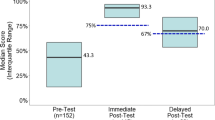

Confidence on Survivorship Topics

Residents were asked about confidence in managing various components of survivorship for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers (Fig. 1). Compared to the 44 residents who responded on the pre-curricular survey, the 40 respondents on the post-curricular survey showed greater confidence across all survivorship topics (p < 0.05). Confidence in genetic risk assessment across cancer types remained low after the curriculum (< 10% very confident on the post-curricular survey).

Practice Patterns on Survivorship Topics

Residents were asked how often they addressed the following aspects of care with cancer survivors at visits: depression screening, assessment for case management/social work referral, and asking about cancer treatment effects. Comparing the pre- to post-curricular survey, residents who reported depression screening “most of the time” or “every time” went from 57 to 82%, those who reported similarly for case management/social work assessment went from 40 to 58%, and those who reported similarly for asking about cancer treatment effects went from 31 to 52% (Supplement C).

Notably, while 17% of residents reported seldom or never asking about cancer treatment effects before the curriculum, only 5% reported seldom (and 0% never) for this topic at the end of the curriculum. The percent of residents asking about cancer treatment effects most of the time doubled (21 to 42%). Overall there was a trend toward residents reporting more frequent discussions of cancer treatment effects on the post-curricular survey (p = 0.07), but no differences over time for depression screening or case management/social work assessment.

Differences in Attitudes, Confidence, or Practice Patterns by Residency Program or PGY Level

On the targeted need assessment, FM residents compared to IM residents rated surveillance for cancer recurrence (mean 4.9 vs 4.4, p = 0.01) and preventive care (mean 5.0 vs 4.7, p = 0.01) with greater importance. Regarding confidence on survivorship topics, before the curriculum, IM residents had higher confidence than FM residents in the areas of breast and prostate cancer surveillance and screening for late effects for all 3 cancers (p < 0.01 to p = 0.03). After the curriculum, IM residents had higher confidence than FM residents in all topics (p < 0.01 to p = 0.046) except monitoring for colorectal cancer recurrence and genetic risk assessment for prostate cancer. There were no differences in attitudes or confidence by PGY level for any of the cancer topics, on either the pre- or post-curricular survey. On both surveys, there were also no differences in responses regarding practice patterns based on residency program or PGY year (comparing PGY 2–3 on the pre-curricular survey, and PGY 1–3 on the post-curricular survey).

Program Evaluation

More than 90% of residents who completed the post-curricular survey felt that each of the curricular components were useful to extremely useful (Fig. 2). At least 85% of residents agreed or strongly agreed with the statements about the curriculum providing opportunities to ask questions, providing an approach to gathering relevant cancer information, and improving the provision of various aspects of cancer survivorship care, with at least 20% strongly agreeing with all of these statements. A quarter of residents strongly agreed that they would recommend this course to other medicine residents, and another 60% of residents agreed.

Over a third of residents reported that a large-group format, the session time, and 2 participating residency programs increased or strongly increased their participation, while nearly half reported increased or strongly increased participation related to the facilitation from the hub team. At least a third to half were neutral on all these aspects of the curriculum.

Knowledge Assessment

Of the 33 residents who completed the 15-question knowledge check on the post-curricular survey, the mean score was 9.4 (63%). The range of scores was 2–13, with the lower scores of 2–3 occurring in PGY-1 residents. There were no statistically different scores based on residency program (p = 0.15) or PGY (p = 0.56). More than half of residents answered 11 of the questions correctly. The four questions that < 50% residents correctly answered (15–48%) were related to side effects of aromatase inhibitors, determining genetic risk in a breast cancer survivor, and treatment related complications in multiple myeloma (two items).

Discussion

The goal of this pilot curriculum was to teach medicine residents a structured approach to cancer survivorship care and improve their confidence in survivorship topics. We provided a tele-educational curriculum through Project ECHO® covering 5 unique cancer types and a variety of survivorship topics in case-based sessions, with expert faculty informing the discussion and teaching. Through eight concise sessions in an academic year, we achieved the following: resident confidence in providing survivorship care improved in a number of survivorship topics, with a trend toward self-reported changes in providing survivorship care. The pilot curriculum was also well-received, with more than 90% of residents rating the curricular components useful and nearly similar rates of perceived improved ability to provide survivorship care. We believe that our study builds on prior cancer survivorship education by targeting a larger number of trainees, specifically medicine residents; nearly three quarters of whom expressed an interest in primary care and/or hospital medicine. Unlike many survivorship educational trainings already available, our curriculum was designed and refined through a year-long curriculum development course with outcomes assessing not only program evaluation but also confidence and impact on future practice. While the COVID pandemic has made the virtual platform prevalent, a synchronous, interactive virtual curriculum for cancer survivorship education is yet novel.

Before and after the curriculum, we asked about confidence in several survivorship topics important for PCPs: cancer surveillance, screening for treatment effects, and genetic risk assessment. Resident confidence in these areas significantly improved across 3 common cancers seen in primary care, which were covered in 6 session cases (3 breast cancer, 2 prostate, 1 colorectal). In a prior survey by Susanibar et al., PGY-3 family and internal medicine residents reported low confidence in survivorship topics, with only 21% feeling very confident in addressing cancer treatment effects [3]. While our residents reported similar rates of feeling very confident addressing treatment effects on the post-curricular survey (18–25% across breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers), 82–88% felt at least somewhat confident in addressing this topic across the three cancer types. Of note, our residents spanned PGY 1–3 (and there were no statistical differences by PGY), and confidence was higher compared to the pre-curricular survey, when < 10% of residents reported feeling very confident.

With an increase in confidence, we saw a similar trend in related practice patterns. We asked residents about their frequency of depression screening, assessing for case management/social work needs, and asking about cancer treatment effects. Our curriculum most directly provided education on cancer treatment effects, and it was encouraging that this was the area that we saw a trend in residents reporting more frequent provision of care after the curriculum (p = 0.07).

The post-curricular survey provided feedback to inform next steps for our pilot curriculum. Notably more than 90% of residents reported that each of the curricular components (case, case discussion, didactic teaching) were useful, suggesting that the overall Project ECHO® format was well received. We felt that the case presentation and related discussion were particularly important and therefore were allotted most of the session time. Some of the constructive feedback suggested spending more time reviewing surveillance guidelines for each cancer type. Because of the emphasis on the case and its clinical questions, we acknowledge that guidelines may not have been emphasized depending on the session’s discussion, especially given our short 45-min sessions. These constraints suggest the need for more sessions and repeating cancer themes (e.g., breast cancer survivorship — surveillance testing, breast cancer survivorship — treatment effects). Despite this feedback, nearly 90% of residents agreed or strongly agreed that they would provide surveillance testing more appropriately as a result of the curriculum. Additionally, more than 90% of residents agreed or strongly agreed that the curriculum taught them a useful approach for gathering cancer-related information for a patient, and that they would monitor for treatment effects more often in their patients as a result of the curriculum.

We also asked about potential factors that may have impacted session participation. While 22% of residents reported that the large group format decreased their participation, our large-group format was in line with the general average ECHO® size of 18–20 participants (personal communication, ECHO® Program Specialist, September 14, 2021). The large-group setting is also typical for residency talks, and in fact, 40% of residents reported increased participation due to the group size. We acknowledge that smaller sessions could provide more opportunities for discussion and may better fit certain learners; however, 90% of residents felt that there were opportunities to ask questions with the large group and overall 85% of residents said that they would recommend this course to other medicine residents.

There are several limitations in our curriculum. While we hoped to have robust pre- and post-curricular knowledge assessments, due to the low participation in the session knowledge checks (and different residents participating per session), it was difficult to make comparisons to the post-curricular knowledge assessment. Given time constraints and resources, we also did not perform standard setting to determine what score would count as having a “minimally competent learner” in survivorship care after the curriculum [29]. However, without standard setting, it was clear that there were knowledge gaps at the end of the curriculum, e.g., the four questions that < 50% of residents answered correctly; these topics may benefit from additional teaching in future iterations of the curriculum. Ideally we would have measured outcomes that would demonstrate behavior or practice change in the care of cancer survivors; however, we were limited in the resources available to measure such changes in residents and may not have expected them with the relatively small number of sessions attended in our pilot curriculum. Multiple longitudinal assessments may also be needed in order to observe these changes.

Having residents as the target learners also presented challenges. The mean number of sessions attended by residents was three, which may have been due to competing clinical responsibilities or being on non-ambulatory rotations. Participation may have been hindered by possible resident hesitancy to speak on topics in which they had less experience or comfort. Fortunately we had support from the residency program leadership for our curriculum, as it was developed in response to the needs expressed by the residency assistant program directors.

Despite the limitations and challenges, our curriculum was able to improve resident confidence in providing survivorship care, in a way that residents perceived as useful and would lead to better survivorship care in their practice. Even with the COVID-19 pandemic, this pilot curriculum was able to go forward by being virtual, and allowed us to draw expert discussants from the hub site. We are considering ways to make this curriculum sustainable and to expand across residency programs. The main barrier to continuing the curriculum is related to funding, which supports faculty and staff time. A facilitator for continuing the curriculum includes the flexibility suggested in some reported factors impacting participation; at least a third to half of residents were neutral on the large-group format, the session time, 2 participating residency programs, and the hub team providing the facilitation. These may be aspects of the curriculum that can be modified in future iterations. The spoke site is discussing launching a comparable curriculum with expert discussants from their own institution. Similarly, the hub site is looking for ways to adapt some of the sessions into a different resident conference series (morning report) at their institution. Given the continued room for improvement in confidence and knowledge after our 1-year curriculum, particularly in the area of genetic risk assessment, there may be a benefit to planning a 3-year curricular cycle covering the duration of FM and IM residency training. By providing comprehensive residency education on survivorship topics, we can better equip future medicine physicians to care for the growing population of cancer survivors.

Conclusion

An eight-session, case-based curriculum on cancer survivorship provided residents an approach to gathering cancer-related patient information, and improved resident confidence and their perceived ability to provide survivorship care.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

American Cancer Society. 2019. Cancer treatment and survivorship facts and figures 2019–21. ACS. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/survivor-facts-figures.html. Accessed on 23 July 2020.

Chan R, Agbejule OA, Yates PM, Emery J, Jefford M, Koczwara B, Hart NH, Crichton M, Nekhlyudov L (2021) Outcomes of cancer survivorship education and training for primary care providers: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01018-6

Price ST, Berini C, Seehusen D, Mims LD (2020) Cancer survivorship training in family medicine residency programs. J Cancer Surviv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00966-9

Susanibar S, Thrush CR, Khatri N, Hutchins LF (2014) Cancer survivorship training: a pilot study examining the educational gap in primary care medicine residency programs. J Cancer Surviv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0366-2

Shayne M, Culakova E, Milano MT, Dhakal S, Constine LS (2014) The integration of cancer survivorship training in the curriculum of hematology/oncology fellows and radiation oncology residents. J Cancer Surviv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0328-0

El-Shami K, Oeffinger KC, Erb NL, Willis A, Bretsch JK, Pratt-Chapman ML, Cannady RS, Wong SL, Rose J, Barbour AL, Stein KD, Sharpe KB, Brooks DD, Cowens-Alvarado RL (2015) American Cancer Society colorectal cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21286

Meyerhardt J, Mangu PB, Flynn PJ, Korde L, Loprinzi CL, Minsky BD, Petrelli NJ, Ryan K, Schrag DH, Wong SL, Benson AB (2013) Follow-up care, surveillance protocol, and secondary prevention measures for survivors of colorectal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.50.7442

Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, Lavoie EM, Smith JB, Cavaletti G, Chauhan C, Gavin P, Lavino A, Lustberg MB, Paice J, Schneider B, Smith ML, Smith T, Terstriep S, Wagner-Johnston N, Bak K, Loprinzi CL (2014) Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914

Armenian S, Lacchetti C, Barac A, Carver J, Constine LS, Denduluri N, Dent S, Douglas PS, Durand J-B, Ewer M, Fabian C, Hudson M, Jessup M, Jones LW, Ky B, Mayer EL, Moslehi J, Oeffinger K, Ray K, Ruddy K, Lenihan D (2017) Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5400

Boutros C, Tarhini A, Routier E, Lambotte O, Ladurie FL, Carbonnel F, Izzeddine H, Marabelle A, Champiat S, Berdelou A, Lanoy E, Texier M, Libenciuc C, Eggermont AMM, Soria J-C, Mateus C, Robert C (2016) Safety profiles of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies alone and in combination. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.58

Bower J, Bak K, Berger A, Breitbart W, Escalante CP, Ganz PA, Schnipper HH, Lacchetti C, Ligibel JA, Lyman GH, Ogaily MS, Pirl WF, Jacobsen PB (2014) Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: an American Society of Clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4495

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity. CDC. www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/guidelines/adults.html. Accessed on 25 March 2021.

Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, Hansen RN, Sullivan SD, Blazina I, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Deyo RA (2015) The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2559

Escalante C, Manzullo EF (2009) Cancer-related fatigue: the approach and treatment. J General Internal Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1056-z

Hadji P, Aapro MS, Body J-J, Gnant M, Brandi ML, Reginster JY, Carola Zillikens M, Glüer C-C, de Villiers T, Baber R, Roodman GD, Cooper C, Langdahl B, Palacios S, Kanis J, Al-Daghri N, Nogues X, Eriksen EF, Kurth A, Rizzoli R, Coleman RE (2017) Management of aromatase inhibitor-associated bone loss (AIBL) in postmenopausal women with hormone sensitive breast cancer: joint position statement of the IOF, CABS, ECTS, IEG, ESCEO IMS, and SIOG. J Bone Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbo.2017.03.001

Hashmi SK (2016) Basics of hematopoietic cell transplantation for primary care physicians and internists. Prim Care. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2016.07.003

Higano, Celestia and Farrell, Timothy. Overview of approach to prostate cancer survivors. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-approach-to-prostate-cancer-survivors. Accessed on 22 October 2020.

Khatcheressian J, Hurley P, Bantug E, Esserman LJ, Grunfeld E, Halberg F, Alexander Hantel N, Henry L, Muss HB, Smith TJ, Vogel VG, Wolff AC, Somerfield MR, Davidson NE (2013) Breast cancer follow-up and management after primary treatment: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9859

National Cancer Institute. 2015. Coping with advanced cancer choices of care near the end of life. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/advancedcancer.pdf. Accessed on 27 May 2021.

National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. 2015. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, third edition. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/NCP_Clinical_Practice_Guidelines_3rd_Edition.pdf. Accessed on 27 May 2021.

NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Cancer-related fatigue version 1.2020 www.nccn.org. Accessed on 24 August 2020.

NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Cancer survivorship version 2.2020. www.nccn.org. Accessed on 24 August 2020.

NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Colon cancer version 4.2020. www.nccn.org. Accessed on 24 August 2020.

NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Rectal cancer version 6.2020. www.nccn.org. Accessed on 24 August 2020.

Postow, Michael. Toxicities associated with checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/toxicities-associated-with-checkpoint-inhibitor-immunotherapy/. Accessed on 28 January 2021.

Resnick M, Koyama T, Fan K-H, Albertsen PC, Goodman M, Hamilton AS, Hoffman RM, Potosky AL, Stanford JL, Stroup AM, Lawrence Van Horn R, Penson DF (2013) Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1209978

Rock C, Thomson C, Gansler T, Gapstur SM, McCullough ML, Patel AV, Andrews KS, Bandera EV, Spees CK, Robien K, Hartman S, Sullivan K, Grant BL, Hamilton KK, Kushi LH, Caan BJ, Kibbe D, Black JD, Wiedt TL, McMahon C, Sloan K, Doyle C (2020) American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21591

Zonder, Jeffrey and Schiffer, Charles. Multiple myeloma: Prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients receiving immunomodulatory drugs (thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/multiple-myeloma-prevention-of-venous-thromboembolism-in-patients-receiving-immunomodulatory-drugs-thalidomide-lenalidomide-and-pomalidomide/. Accessed on 25 February 2021.

Cizek G, Bunch M (2007) Standard setting: a guide to establishing and evaluating performance standards on tests. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985918

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of our expert discussants and the TowerHealth internal medicine and family medicine residents for their participation in our curriculum. We also thank Mary Ellie Alderfer and Melissa Gerstenhaber for their administrative support and Dr. Sean Tackett for his analytic support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Merck Foundation (grant number N022890).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board provided an exemption for this study.

Informed Consent

Data was de-identified for analysis, and no consent was required for ethical approval.

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Brown, Choi, Murillo, Nesfeder, and Peairs and Ms. Bugayong have received salary support from a Merck Foundation Grant. Dr. Chodoff has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, Y., Chodoff, A.C., Brown, K. et al. Preparing Future Medicine Physicians to Care for Cancer Survivors: Project ECHO® in a Novel Internal Medicine and Family Medicine Residency Curriculum. J Canc Educ 38, 608–617 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-022-02161-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-022-02161-z