Abstract

Patients with colorectal cancer may lack information about the disease and treatment. In 2017, a group consultation before start of surgery was introduced at a university hospital in western Sweden to inform about the disease, treatment, and ongoing scientific studies. The primary aim of this study was to explore the experience of the patients attending the group consultation. Based on semi-structured interviews with patients with colorectal cancer, a questionnaire was constructed and administered to patients, both those attending and those not attending the group consultation. In total, 124 patients were included and the response rate was 86%. A majority of patients attending the group consultation would recommend it to someone else with the same illness. Of the patients attending the group consultation, 81% (30/37) patients agreed, fully or partially, that attending the group consultation had increased their sense of control and 89% (33/37) that the information they received at the group consultation increased their feeling of participation in the treatment. Preoperative group consultation is a feasible modality for informing and discussing the upcoming treatment for colorectal cancer with the patients, and the patients who attended the group setting appreciated it. Attending the group consultation increased the patients’ feeling of active participation in their treatment and their sense of control, which could possibly both improve their experience of their illness and facilitate recovery.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

NCT03888313

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

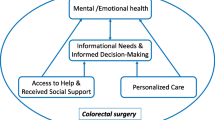

Patients with colorectal cancer receive information at different occasions during the course of the care, both before, during, and after treatment, to increase their ability to cope with their illness and to promote recovery [1]. Group consultation is a comprehensive term to describe care models where several patients are seen by one or more clinicians at the same time. Ideally, the group consultation should deliver support from other patients as well as all other things included in the usual healthcare [2].

Patients with colorectal cancer have been found to lack information on the disease and the treatment [3,4,5]. Patients with poorer physical status as indicated with a higher ASA score, and patients living without a partner, are less satisfied with the information received [3, 6]. Preoperative information and education as a method of improving outcomes for treatment of colorectal cancer has seldom been studied, but one study of patients receiving a stoma concluded preoperative education was more effective than the traditional education given postoperative [7]. Patients receiving radiotherapy and randomized to a diagnose-specific group consultation as well as individual information compared to standard information, were more satisfied compared to patients who received standard information [8]. In a review of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients surviving cancer, it was reported that studies on information and quality of life did not find any positive association between information provision and physical HRQoL [9]. In the same review, however, it was reported that studies have shown that patients receiving clear and high levels of information had better mental and global HRQoL [9, 10].

The specific background to this study is that in 2017, a group consultation inviting patients planned for elective surgery for colorectal cancer was launched at a University Hospital in western Sweden. The consultants and nurses that participated in the group consultation expressed verbally that they found patients appreciative. However, before deciding whether to include the preoperative group consultation into usual care at the University Hospital, an explorative study of the patients’ experience was deemed important. The aim of this study was to investigate how the patients with recently diagnosed colorectal cancer experienced the preoperative group consultation.

Methods

The group consultation was held in a conference room at the hospital. A consultant surgeon and a research nurse were present, and the patients were invited to bring along family members. The session began with a presentation including information about the postoperative mobilization and breaking of fast. When needed, the importance of smoke cessation before surgery was also discussed. This was followed by questions from the patients and relatives about things related to colorectal cancer and the planned treatment. After this questions-and-answers part, information about ongoing clinical trials were given, orally as well as the formal written patient information document.

The data from the questionnaires were supplemented by data retrieved from medical records. The study-specific questionnaire consisted of questions previously used [11, 12] and newly generated questions, developed according to an established method [13, 14]. The new questions were developed by in-depth interviews with patients with colon or rectal cancer before they had gone through surgery. The verbatim transcript of the interviews underwent content analysis, and new questions were constructed based on the themes identified. An expert group selected the questions to be included in the questionnaire, which was then subject to face validation. The face-to-face validation ensured that the questions were easy to comprehend and straightforward to answer. An instrument for assessment of quality of life was included, the five dimensions of the EQ-5D-5L as well as the EQ VAS [15], and questions on socioeconomics and comorbidity. After revisions, the final version of the questionnaire was printed and used in the study. The patients who chose not to attend the group consultation but consented to be included in the study received a specific questionnaire, without questions related to the group consultation.

Patients and Statistics

All patients planned for surgery for colorectal cancer at a university hospital in Sweden were invited to participate in the group consultation on the Friday of the week they had their primary consultation. The patients who chose to attend the group consultation were informed about, and invited to participate in, the study during the group consultation; if they accepted, they also received the questionnaire. The patients who chose not to attend the group consultation were informed and invited to participate in the study at their next visit in the routine pathway (the outpatient pre-operative work-up visit), where they were given the specific questionnaire after informed consent. All questionnaires were accompanied by a pre-paid return envelope. All patients who mailed the questionnaire to the research secretariat received a thank you post card. When possible, patients who had not returned the questionnaire received a reminder either by post card or telephone. No reminder post cards were sent out after the patients undergone surgery.

Since the aim of the study was to explore the experience of the patients attending the group consultation rather than explicit statistical hypothesis testing, no a priori calculation of power was performed. Descriptive statistical methods were used for presenting the demography and the outcome measures, SPSS and R version 3.2.3 [16] were used. In R, the ggplot2 and tidygeocoder packages were used.

The study was preregistered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03888313). Permission was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Sweden (2019-00665/1127-18). Permission to use the EQ-5D 5L [15] was obtained.

Results

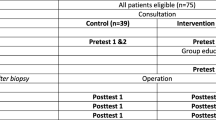

In total, 124 patients were included from April to November 2019. Forty-two patients attended the group consultation and 82 did not. Fifteen patients did not return the questionnaire, rendering a response rate of 86% (Fig. 1). In relation to their first visit at the outpatient clinic, the patients not attending the group consultation completed the questionnaire later than the ones who attended the group consultation (11/72 vs 11/37 within 4 days).

Among the patients who attended the group consultation, there was a tendency that a larger proportion of patients had tertiary or university education (Table 1). The patients attending the group consultation had more comorbidity than the patients who did not attend the group consultation, and their distance to the hospital was shorter. More patients, who did not attend the group consultation, were subject to abdominoperineal resection and had preoperative radiation or chemotherapy. The EQ VAS for the patients who attended the group consultation was median 75.0 (IQR 62.5–85.0, n = 37) and for the patients that did not attend the group consultation median 70.0 (IQR 58.8–80.0, n = 70). The results of the five dimensions of the EQ-5D 5L are presented in Fig. 2. The results indicate that the group who chose not to attend the group consultation more often experienced pain, anxiety/depression, and difficulties performing activities of daily life.

Two-thirds of the patients collected further information about cancer and treatment from other sources than healthcare, and this finding was consistent among the two groups (Table 2). None of the patients had been in contact with patient organizations. Results indicate that a larger proportion of patients among the ones that did not attend the group consultation browsed the internet and the webpage provided by the public healthcare called the Care guide (www.1177.se), than those who attended the group consultation.

Among the patients attending the group consultation, 15/36 stated that they wanted information both at the group consultation and at their ordinary visit to the outpatient clinic. Further, 2/36 stated that they wanted information on scientific studies at the out-patient clinic only and 9/36 at the group consultation only.

Of the 37 patients attending the group consultation, 35 would recommend someone with the same condition to attend (Table 3). About 90% agreed, fully or partly, that their participation at the group consultation increased their understanding of the planned treatment (34/37) and increased their feeling of involvement in the treatment (33/37). Three patients stated that their participation in the group consultation did not increase their sense of control; however, the remaining 80% (30/37) agreed, fully or partly, with the statement about increased sense of control. A majority (24/37) were positive regarding group consultation; 19/37 also stated that it was possible to raise difficult questions, and 21/37 appreciated meeting others with the same disease.

Discussion and Conclusions

Discussion

In short, the patients attending the group consultation would recommend it to someone else and the group setting was a positive experience. A large proportion of patients agreed that the group consultation increased their sense of control and feeling of participation in their own treatment.

Patients planned for treatment for colorectal cancer attending the group consultation experienced that it increased their sense of control and their active participation in the treatment. This is corroborated by a previous study on the preoperative nurse information session as part of the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programme, which concluded that it made the patients more active in their own recovery after surgery [17]. The result of this study was that a large proportion of patients, who did not attend the group consultation, browsed the internet for more information on their cancer and the associated treatment. A previous study found that a majority of patients felt that the information on the internet made them feel empowered to make decisions about their health and helped them talk to their doctor about their health [18]. However, a number of the patients felt that the information could be overwhelming and made them aware of conflicting medical information about their cancer. This can be exemplified by a recent assessment of quality and accuracy of online information for patients with low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) where information on incidence often were lacking [19]. In contrast, the information given at the group consultation is based on science and proven experience from healthcare professionals. In conclusion, as a lot of patients with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer search the internet with varying results, the group consultation seems a good way of educating patients.

The strengths of this study were the study-specific questionnaire developed by interviews with patients and face validation before use. Further, the high response rate ensured reliable results. One limitation was the possible selection bias, meaning that all patients were invited to the group consultation but we found indications that those patients who chose to attend differed in some aspects, such as pain, anxiety, and distance to the hospital. Consequently, comparisons between groups were made with caution. Furthermore, the number of patients included did not provide power for statistical analyses regarding differences between the two groups of patients, but for this explorative study the design was considered suitable.

In a time of abundant information available from many sources, the validated information provided by healthcare personnel is important for patients recently diagnosed with colorectal cancer [20]. The patient browses different information sources, not always finding reliable or accurate descriptions of the disease and the treatment options. In light of this, one important task for the healthcare is to give patients facing cancer treatment accurate and reliable information. The consultation with the surgeon delivering the diagnosis of cancer can be stressful and retention of the large amounts of information difficult [21]. To educate patients through group consultations can be an appropriate method, to supplement the standard consultations where diagnosis is confirmed, and treatment options discussed. Some information before surgery could be given in a group setting with ample time for any questions the participating patients wish to raise. The questions raised by one patient may support others to actively participate and gather information.

Conclusions

Preoperative group consultation is a feasible modality for delivering supplemental information to patients before treatment of colorectal cancer and to inform of ongoing clinical studies. The benefits of the group consultation following the standard visit to the outpatient clinic, could be to supplement the information found on the internet and through other sources, to answer and discuss issues appearing after the initial patient-surgeon consultation, and to increase of the patient’s participation in their treatment.

Practical Implications

For the patients with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer who chose to attend the group consultation, it was found to have several benefits. To introduce it permanently in the care prior to surgery for colorectal cancer could probably increase the attending patients’ feeling of being in control and their active participation in their own treatment.

Data Availability

The data is available through contact with the corresponding author.

References

Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV (2011) The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 22 (4):761–772. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq413

Jones T, Darzi A, Egger G, Ickovics J, Noffsinger E, Ramdas K, Stevens J, Sumego M, Birrell F (2019) PROCESS AND SYSTEMS: A systems approach to embedding group consultations in the NHS. Future Healthc J 6(1):8–16. https://doi.org/10.7861/futurehosp.6-1-8

Lithner M, Jakobsson U, Andersson E, Klefsgard R, Palmquist I, Johansson J (2015) Patients’ perception of information and health-related quality of life 1 month after discharge for colorectal cancer surgery. J Cancer Educ 30(3):514–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-014-0735-6

Kotronoulas G, Papadopoulou C, Burns-Cunningham K, Simpson M, Maguire R (2017) A systematic review of the supportive care needs of people living with and beyond cancer of the colon and/or rectum. Eur J Oncol Nurs 29:60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2017.05.004

Walming S, Asplund D, Block M, Bock D, Gonzalez E, Rosander C, Rosenberg J, Angenete E (2018) Patients with rectal cancer are satisfied with in-hospital communication despite insufficient information regarding treatment alternatives and potential side-effects. Acta Oncol 57(10):1311–1317. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2018.1484158

Husson O, Thong MS, Mols F, Oerlemans S, Kaptein AA, van de Poll-Franse LV (2013) Illness perceptions in cancer survivors: what is the role of information provision? Psychooncology 22 (3):490–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3042

Chaudhri S, Brown L, Hassan I, Horgan AF (2005) Preoperative intensive, community-based vs. traditional stoma education: a randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum 48(3):504–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-0897-0

Häggmark C, Bohman L, Ilmoni-Brandt K, Näslund I, Sjödén PO, Nilsson B (2001) Effects of information supply on satisfaction with information and quality of life in cancer patients receiving curative radiation therapy. Patient Educ Couns 45(3):173–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00116-1

Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV (2011) The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 22(4):761–772. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq413

Kerr J, Engel J, Schlesinger-Raab A, Sauer H, Holzel D (2003) Doctor-patient communication: results of a four-year prospective study in rectal cancer patients. Dis Colon Rectum 46 (8):1038–1046. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.dcr.0000074690.73575.99

Asplund D, Heath J, Gonzalez E, Ekelund J, Rosenberg J, Haglind E, Angenete E (2014) Self-reported quality of life and functional outcome in patients with rectal cancer--QoLiRECT. Dan Med J 61(5):A4841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05810-5

Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, Dickman PW, Johansson JE, Norlen BJ, Holmberg L (2002) Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med 347(11):790–796. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa021483

Omerov P, Steineck G, Runeson B, Christensson A, Kreicbergs U, Pettersen R, Rubenson B, Skoogh J, Radestad I, Nyberg U (2013) Preparatory studies to a population-based survey of suicide-bereaved parents in Sweden. Crisis 34(3):200–210. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000175

Steineck G, Bergmark K, Henningsohn L, al-Abany M, Dickman PW, Helgason A (2002) Symptom documentation in cancer survivors as a basis for therapy modifications. Acta Oncol 41(3):244–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860260088782

Devlin NJ, Brooks R (2017) EQ-5D and the EuroQol Group: past, present and future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 15(2):127–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-017-0310-5

Core Team R (2014) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing

Aasa A, Hovback M, Bertero CM (2013) The importance of preoperative information for patient participation in colorectal surgery care. J Clin Nurs 22(11–12):1604–1612. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12110

Fleisher L, Bass SB, Ruzek SB, McKeown-Conn N (2002) Relationships among Internet health information use, patient behavior and selfefficacy in newly diagnosed cancer patients who contact the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Atlantic Region Cancer Information Service (CIS). Amia 2002 Symposium, Proceedings:260–264

Islind AS, Johansson V, Vallo Hult H, Alsen P, Andreasson E, Angenete E, Gellerstedt M (2020) Individualized blended care for patients with colorectal cancer: the patient's view on informational support. Support Care Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05810-5

Islind AS, Johansson V, Vallo Hult H, Alsen P, Andreasson E, Angenete E, Gellerstedt M (2020) Individualized blended care for patients with colorectal cancer: the patient's view on informational support. Support Care Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05810-5

Nguyen MH, Smets EMA, Bol N, Bronner MB, Tytgat Kmaj, Loos EF, van Weert JCM (2019) Fear and forget: how anxiety impacts information recall in newly diagnosed cancer patients visiting a fast-track clinic. Acta Oncol 58(2):182–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186x.2018.1512156

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. The authors gratefully acknowledge the work by the research nurses at the Scandinavian Surgical Outcomes Research Group, SSORG, and by all those involved in the recruitment of patients at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital/Östra, Göteborg.

Funding

The Health-care sub-committee of Region Västra Götaland, ALF grant ‘Agreement concerning research and education of doctors´ (ALFGBG-718221), the Gothenburg Medical Society and Anna-Lisa and Bror Björnsson’s Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SW, EA, DB, MB, HC, and AW contributed to the design of the study and development of the study-specific questionnaire. All authors contributed the analysis plan and SW performed the analyses. SW, EA, DB, MB, HC, AW, and EH contributed to the drafting and finalizing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Code Availability

The statistical software used were SPSS and R version 3.2.3. In R, the ggplot2 and tidygeocoder packages were used.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Walming, S., Angenete, E., Bock, D. et al. Preoperative Group Consultation Prior to Surgery for Colorectal Cancer—an Explorative Study of a New Patient Education Method. J Canc Educ 37, 1304–1311 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01951-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01951-7