Abstract

This study examined the role of sociodemographic characteristics, health insurance, cancer knowledge, perceived health risk, and having a recent physicians’ visit on breast and cervical cancer screening utilization among a randomly selected group of Chamorro women (n = 250) residing in San Diego, California. Data were collected by a telephone survey and analyzed using multiple logistic regression models. After adjusting for covariates, having a recent full exam was the strongest predictor of having had a Pap exam in the past 2 years for women 21 years and older and a clinical breast exam in the past 2 years for women 40 years and over.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The National Institutes of Health considers Pacific Islanders to be an underserved and disadvantaged ethnic subgroup [1]. Chamorros, Micronesians, Tongans, and Samoans are the four main groups within the Pacific Islander populations. The Chamorro community is made up of people indigenous to the Mariana Islands, with Guam and Saipan being home to the top two largest populations. In 2003, the leading causes of death for Asian Americans and Pacific Islander (AAPI) were: cancer (26.2%), diseases of the heart (25.3%), and cerebrovascular disease (9.0%) [2]. Among all US ethnic groups from 1999 to 2003, AAPI women had the lowest age-adjusted overall cancer incidence and mortality rates [3]; however, breast cancer is the most common cancer for Pacific Islander women [4] and for Chamorro women living in Guam [5].

With cancer as a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, intervention efforts are hampered by the limited cancer-related data available to guide the creation of tailored cancer control programs [6–12]. There are few published studies focused on predictors of cancer screening targeted for the individual communities within the Pacific Islander subgroups [13–15]. Of the published studies, most focus on the Chamorro community in Guam, on noncancer health problems, or are outdated [9, 16–29]. With San Diego, California being home to the largest urban population of Chamorros outside of Guam [4, 7, 20], the authors were specifically interested in identifying data related to health promotion practices and cancer screening that could be applied to improving the health of that community [9, 12, 30].

The San Diego Chapter of the National Cancer Institute-funded Pacific Islander Cancer Control Network’s (PICCN) Board of Directors hypothesized that Chamorro women would be models of optimal health practices. They based their assumption on the fact that many Chamorro families had access to health care through the military and, as military families, they were more likely to have a positive orientation to following directives. Furthermore, since English literacy is high among Chamorros, health literacy would also likely be high and thereby contribute to better-than-average health knowledge and practices. The leaders of the PICCN invited faculty at UCSD to assist them in evaluating the accuracy of their assumptions. Additionally, since only limited research has been conducted with Chamorro women, this study was also designed to explore predictors of cancer screening.

Materials and Methods

-

Hypothesis #1:

Chamorro women would be models of optimal health practices.

-

Hypothesis #2:

Sociodemographic characteristics, baseline knowledge, and health care variables would significantly predict the likelihood of recent cancer screening.

Participant Recruitment

PICCN board members set up meetings with each of the 11 Chamorro community leaders/members at their monthly meetings to raise awareness of the importance of this community–campus partnership project and to ask for their cooperation in promoting the community members’ involvement. The recently updated Chamorro Directory International (a telephone directory composed exclusively of those who have self-identified as members of the Chamorro communityFootnote 1) was used to identify Chamorros living in San Diego. All San Diego entries in the directory were entered into a database and randomly contacted using a computer-generated call list. If a female answered the phone, she was invited to complete the survey if she was at least 21 years of age and reported herself to be of Chamorro descent. If a male answered the phone, he was asked to pass the phone call to any female in the household who met the above qualifications. Using an institutional review board-approved oral consent protocol, bilingual female university students placed calls throughout the day and evening, 7 days a week, to ensure a diverse sample with minimal selection bias.

Up to 10 attempts were made to reach each computer-generated name. Once an eligible woman was reached, surveyors followed a telephone script to assure that the health-related survey data would be gathered consistently. Potential participants were given the option of conversing in Chamorro.

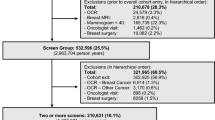

To reach the sample goal of 250 Chamorro women, the surveyors attempted to reach 1,144 of the 1,245 women in the database. Of the 894 other women for whom up to 10 call attempts were made, two participants provided incomplete data, 421 attempts failed due to the phone being disconnected, a wrong number, or the person moved. Of the remainder, 179 were not interested in participating, 70 resulted in no answer, 34 had no eligible woman available to take the call, and the remainder either offered other reasons (n = 20) or no reason.

Sample Description

Participants’ ages ranged from 21 to 91 years old (M = 40.4, SD = 13.0, n = 243). The majority (67.6% n = 169) reported being born in the Mariana Islands, with 30.4% (n = 76) in the US mainland and 2.0% (n = 5) elsewhere. For women who were not born in the US mainland, they reported moving to the mainland at 19 years of age on average (SD = 13.0, n = 172). Nearly all women (83.2%, n = 208) reported living in the continental United States for most of their lives, while the remainder reported living in Guam most of their lives (14.4%, n = 36) and the rest (2.4%) had spent most of their lives elsewhere. None of the participants availed themselves of the option of conversing in Chamorro, preferring to use English. Over half had completed at least some college (53.8%, n = 133; Table 1). Participants were most likely to report a health care provider as the number 1 source of health information compared to other sources (Table 2).

Data Analysis

Logistic regression models were used to examine the relationship between all explanatory variables and the two outcomes of interest: a Pap exam in the preceding 2 years for women 21 years and older and a clinical breast examination (CBE) in the preceding 2 years for women 40 years and older. (For this study, women were not asked about their most recent mammogram.) A time frame of 2 years was selected as a reasonable window for defining recent screening behaviors given the fact that screening guidelines vary [31, 32] and studies generally report recent breast and cervical cancer screening in the previous 2 years [33–36]. Explanatory variables were: recent physicians visit in the preceding 2 years, health insurance, education, age, place of birth (US mainland or Mariana Islands), self-reported adequacy of cervical and breast cancer knowledge, and perceived health risks among Chamorro women (e.g., cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease) [9, 12, 18, 30]. Separate logistic regression models were run for each screening modality (e.g., for recent Pap exam and recent CBE). Simple logistic regression models were run to determine the unadjusted odds ratios (OR) for each independent variable. Multivariate logistic regression models were run including significant unadjusted independent variables to determine the adjusted OR. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 14.0.

Results

Hypothesis #1 was Proven True

Women’s likelihood of having health insurance and rates of Pap exams were consistently higher than the average in California and the nation.

Most of the sample (93.1%, n = 230) reported having health insurance, and this was at a rate that was higher than national and state percentages. In 2004, 84.3% of the nation had health insurance and, from 2002 to 2004, 81.6% of Californians had health insurance [37].

Many of the sample’s Chamorro women (78.9%, n = 168) reported having had a Pap exam within the previous 2 years,Footnote 2 with 92.6% (n = 199) in the previous 3 years. In 2004, 85.9% of the women nationally and 84.8% of California women had a Pap exam in the previous 3 years (http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.htm).

Depending on the screening guidelines used for CBE, 42.9% (n = 66) of the Chamorro women 40 years and older had a CBE in the past year and 74% (n = 144) had a CBE in the past 2 years (see Table 2). Equivalent state and national data were not available for CBE.

When asked to list the most commonly occurring diseases among Chamorro women, they listed the correct diseases for the AAPI community, although not in the exact order of magnitude. Study participants listed: diabetes (33.5%, n = 83); cancer (33.1%, n = 82); cerebrovascular disease (15.7%, n = 39); heart disease (13.7%, n = 34); and other (4.0%, n = 10; Table 2). In 2003, the leading causes of death for the AAPI community were cancer (26.2%), diseases of the heart (25.3%), cerebrovascular disease (9.0%), and accidents/unintentional injuries (4.9%) [2].

Hypothesis #2 was Partially Supported

Adjusting for all other variables, a recent full exam significantly predicted the likelihood of recent CBE and Pap exam.

Table 3 displays the results from the simple logistic regression analyses revealing unadjusted OR and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for both recent Pap exam and recent CBE models. Having a recent full exam in the previous 2 years (OR = 28.191), being born in the US mainland (OR = 2.596), self-reported adequacy of cervical cancer knowledge (OR = 2.153), and breast cancer knowledge (OR = 2.370) were significant independent predictors of having had a recent Pap exam. Increasing age (OR = 0.950) was inversely related to having had a Pap exam.

Having a recent full exam in the previous 2 years (OR = 16.406) and self-reported adequacy of breast cancer knowledge (OR = 2.221) were significant independent predictors of having had a recent CBE for women 40 years and older.

Table 4 displays the results from the multivariate logistic regression analyses revealing the adjusted OR and corresponding 95% CI for both recent Pap exam and recent CBE models. Adjusting for all other variables in the model (place of birth, perceived cervical cancer knowledge, and perceived breast cancer knowledge), having a recent full exam in the previous 2 years (OR = 42.703) was a significant predictor of having a recent Pap exam and increasing age (OR = 0.929) continued to be inversely related to the likelihood of having had a recent Pap exam. Adjusting for the other variable in the model (breast cancer knowledge), having a recent full exam in the previous 2 years (OR = 15.344) was a significant predictor of having had a recent CBE exam for women 40 years and older. Thus, after adjusting for all other variables, having had a recent full exam was the most significant predictor of likelihood of recent breast and cervical cancer screening.

Discussion

Results showed that, after adjusting for covariates, having had a recent full exam was the strongest predictor of a recent Pap exam for women 21 years and older and recent CBE for women 40 years and over. While being younger predicted the likelihood of having had a Pap exam, cervical cancer is a concern for women of all ages. While there were relatively high rates of cervical screening compared to state and national averages, the annual CBE rate was still only 42.9% and 74% for the past 2 years, offering another area in which cancer educators and primary care providers could be focusing on increasing screening rates.

For health educators and health care providers, this study’s findings underscore the importance of promoting women’s annual physical examinations. No other independent variable was more predictive of adherence to CBE and Pap exam guidelines than undergoing an annual examination. The encouragement to have an annual physical examination thus appears to be the single most important message health educators need to convey. The Foot-in-the-Door theory [38, 39] has potential applications here. Once a woman has committed to undergoing an annual exam, she may be likely to be more receptive to other recommendations for screening, and this may be particularly so for these Chamorro women who report that their health care provider is their leading source of health care information.

Thus equally important, the clinicians must be vigilant in assuring that, when women do come for their annual exams, they are offered the full panel of recommended screening guidelines. Since the annual exam is so highly correlated with adherence to screening guidelines, those health care providers who have systems that remind women that it is time for their annual examination will be simultaneously increasing adherence to screening guidelines. This finding raises concern for the well being of those women who do not have a regular physician or those who do not routinely see any doctor. They may be the most at-risk group for late-stage cancer detection. Studies have addressed the potential value of offering cancer screening recommendations in the emergency department and urgent care clinics, places that may be particularly important for those women without regular contact with a health care provider [40–43].

Limitations of this study were the narrow geographic area from which the study participants were recruited and the participants’ high rates of health insurance coverage and levels of education that may have positively biased this sample’s cancer screening behaviors in comparison to Chamorros living in other parts of the country. However, the 250 women who participated in this study represent a relatively large sample size given the size of the mainland Chamorro population and when compared to previous studies and this may offer some compensation. Of the Chamorro women in the continental United States, previous sample sizes range from 128 to 404 Chamorro women (i.e., [4, 5, 9, 12, 18, 30, 44]).

A strength of this study was the community–campus partnership that prompted this study and that the study’s questions arose from the community itself. As a result, the PICCN’s board members actively promoted study participation throughout San Diego’s Chamorro community. The Chamorro Directory International proved to be another important strength of the study. The community took pride in updating and expanding their directory, and ultimately, creating a research tool of considerable value in making a community needs assessment. As a result, it proved useful in identifying and recruiting a diverse sample of Chamorros, an otherwise difficult task to accomplish in such a close-knit, yet “hard-to-reach” community. In spite of these strengths, generalizations must be made with caution.

Conclusion

Additional studies are required to further investigate the causal role of access to health care (e.g., quality and type of health insurance) and cultural health beliefs in relation to cancer screening and rescreening among Chamorro women living in the mainland United States.

Notes

The Chamorro Directory International is a private project of Lee Ann Cruz as a tool to help Chamorros contact other Chamorros in the mainland United States. The database is updated continually. It has proven to be a very important reference not only for the Chamorro community, but also for the medical/health/research/academic societies.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends to start Pap screening 3 years after vaginal intercourse, no later than age 21, and to continue annually. After 30 and three or more normal Pap tests, women should screen every 2–3 years (http://ahrq.gov).

References

National Cancer Institute (NCI) (2005) Cancer health disparities: a fact sheet. Available at http://www.cancer.gov/newscenter/benchmarks-vol5-issue6/page2. Accessed 15 April 2007

Heron MP, Smith BL (2007) Deaths: leading causes for 2003. National Vital Statistics Reports 55(10). Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr55/nvsr55_10.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2007

American Cancer Society (ACS) (2007) Cancer facts & figures, 2007. American Cancer Society, Atlanta

Tanjasiri SP, Sablan-Santos L (2001) Breast cancer screening among Chamorro women in Southern California. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 10(5):479–485

Cruz AL et al (2008) Breast cancer screening among Chamorro women in California. Cancer Detect Prev 32(Suppl 1):S16–S22

Haddock RL, Naval CL (2002) Cancer on Guam, especially among Micronesians. Pac Health Dialog 9(2):222–224

Hubbell FA et al (2004) Addressing the cancer control needs of Pacific Islanders: experience of the Pacific Islander Cancer Control Network. Pac Health Dialog 11(2):233–238

Hubbell FA et al (2006) Legacy of the Pacific Islander Cancer Control Network. Cancer 107(8 Suppl):2091–2098

Nguyen V et al (2003) Cancer risk factor assessment among Chamorro women. J Cancer Educ 18(2):100–106

Palafox NA, Tsark J (2004) Cancer in the US Associated Pacific Islands (UASPI): history and participatory development. Pac Health Dialog 11(2):8–13

Tanjasiri SP et al (2004) Exploring access to cancer control services for Asian-American and Pacific Islander communities in Southern California. Ethn Dis 14(3 Suppl 1):S14–S19

Wu PL et al (2004) Cancer risk factor assessment among Chamorro men in San Diego. J Cancer Educ 19(2):111–116

Amin A et al (2008) Breast cancer screening compliance among young women in a free access healthcare system. J Surg Oncol 97(1):20–24

Balajadia RG et al (2008) Cancer-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among Chamorros on Guam. Cancer Detect Prev 32(Suppl 1):S4–S15

Chen JY et al (2004) Disaggregating data on Asian and Pacific Islander women to assess cancer screening. Am J Prev Med 27(2):139–145

Alur P et al (2002) Epidemiology of infants of diabetic mothers in indigent Micronesian population—Guam experience. Pac Health Dialog 9(2):219–221

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2005) Diabetes-related preventive care practices—Guam, 2001–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 54(13):333–335

Chiem B et al (2006) Cardiovascular risk factors among Chamorros. BMC Public Health 6:298

Greer MH, Larson K, Sison S (2003) Comparative analysis of oral health indicators among young children in Hawai’i, the Republic of Palau and Territory of Guam, 1999–2000. Pac Health Dialog 10(1):6–11

Hardy J et al (2002) Clinical features and changing patterns of neurodegenerative disorders on Guam, 1997–2000. Neurology 59(7):1121 author reply 1121

McGeer PL et al (1997) Familial nature and continuing morbidity of the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis–parkinsonism dementia complex of Guam. Neurology 49(2):400–409

Mokuau N (1996) Health and well-being for pacific islanders: status, barriers and resolutions. Responding to Pacific Islanders: culturally competent perspectives for substance abuse prevention. Available at http://erc.msh.org/staticpages_printerfriendly/8.5.1_provider_english.htm. Accessed 15 April 2007

Morris HR et al (2001) A clinical and pathological study of motor neurone disease on Guam. Brain 124(Pt 11):2215–2222

Morris HR et al (2004) Genome-wide analysis of the parkinsonism–dementia complex of Guam. Arch Neurol 61(12):1889–1897

Pinhey TK (1995) The health status and characteristics of hypertensives in Guam. Asia Pac J Public Health 8(3):177–180

Pinhey TK, Iverson TJ, Workman RL (1994) The influence of ethnicity and socioeconomic status on the use of mammography by Asian and Pacific island women on Guam. Womens Health 21(2):57–69

Steele JC (2005) Parkinsonism–dementia complex of Guam. Mov Disord 20(Suppl 12):S99–S107

Torsch V (2002) Living the health transition among the Chamorros of Guam. Pac Health Dialog 9(2):263–274

Workman RL et al (2002) Highlights of findings from the 1999 Guam study of youth risk behaviors. Pac Health Dialog 9(2):233–236

Wu PL et al (2005) Diabetes management in San Diego’s Chamorro community. Diabetes Educ 31(3):379–390

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (2006) The guide to clinical preventive services: recommendations of the U.S. preventive services task force. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at http://pda.ahrq.gov. Accessed 1 May 2007

American Cancer Society (ACS) (2008) California cancer facts & figures, 2008. Available at http://www.ccrcal.org/PDF/ACS2008.pdf. Accessed 14 February 2008

Abraido-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Gammon MD (2004) Breast and cervical cancer screening among Latinas and non-Latina whites. Am J Public Health 94(8):1393–1398

De Alba I et al (2005) Impact of U.S. citizenship status on cancer screening among immigrant women. J Gen Intern Med 20(3):290–296

Hubbell FA et al (1997) The influence of knowledge and attitudes about breast cancer on mammography use among Latinas and Anglo women. J Gen Intern Med 12(8):505–508

Jones AR, Caplan LS, Davis MK (2003) Racial/ethnic differences in the self-reported use of screening mammography. J Community Health 28(5):303–316

DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Lee CH (2005) Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2004. Current Population Reports, P60-229, U. S. Governmental Printing Office, Washington, DC. Available at http://www.census.gov/prod/2005pubs/p60-229.pdf. Accessed 16 January 2008

Burger JM (1999) The foot-in-the-door compliance procedure: a multiple-process analysis and review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 3(4):303–325

Pascual A, Gueguen N (2005) Foot-in-the-door and door-in-the-face: a comparative meta-analytic study. Psychol Rep 96(1):122–128

Batal H et al (2000) Cervical cancer screening in the urgent care setting. J Gen Intern Med 15(6):389–394

Hogness CG et al (1992) Cervical cancer screening in an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 21(8):933–939

Mandelblatt J et al (1997) The costs and effects of cervical and breast cancer screening in a public hospital emergency room. The Cancer Control Center of Harlem. Am J Public Health 87(7):1182–1189

Mandelblatt J et al (1996) Implementation of a breast and cervical cancer screening program in a public hospital emergency department. Cancer Control Center of Harlem. Ann Emerg Med 28(5):493–498

Tanjasiri SP et al (2008) Promoting breast cancer screening among Chamorro women in Southern California. J Cancer Educ 23(1):10–17

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by a National Cancer Institute grant R25CA65745, a San Diego County Mini Grant, a National Institutes of Health Summer Research Training Grant, a P30 CURE Grant, a UCI/PICCN grant L00-CA-86073-5, and a National Institutes of Health Division of National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities EXPORT grant P60MD00220. Generous contributions of educational materials were made by the American Cancer Society; American Diabetes Association; California Department of Health Services; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Institutes of Health; the Pacific Islander Cancer Control Network; San Diego County’s Reduce or Eliminate Health Disparities With Information; and United States Department of Agriculture. The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official beliefs of the funding agencies. The authors acknowledge the help of the following Pacific Islander Cancer Control Network (PICCN) board members: Lillian A. Blas, Frances G. Benito, Annabelle L. Cruz, MSW, Evelyn B. Blas, Rose P. Treltas, Tara Blas, Rachel Acfalle, Beverly Acfalle, Alicia Simpliciano, and Nicole Johnson. The following community leaders played key roles in encouraging and disseminating information: Agat Social Club of California: Guadalupe Castro Rabon, Asan Nino Perdido y Sagrada Familia: Bernie Toves Iseman, Barrigada San Roke Fiesta Group: Thomas Guzman, Inarajan/St. Joseph Fiesta Group: John Fejeran, Mangilao/Santa Teresita Foundation: Jeanette Perez Charfauros, Oceanside/San Luis Rey Guamanian Community: Tom Cruz, San Dimas/Merizo Guam Club of California: Joaquin Naputi, Santa Rita Fiesta Group: Eloise M. Gogue, Sons and Daughters of Guam Club, Inc: John S. Cruz, Sinajana/St. Jude Fiesta Group: Jesus Perez, and Yona/St. Francis Fiesta Group: Jesus Y. Quitugua. In addition, the authors thank Drs. Allan Hubbell and Maria Reyes of UCI for their help with this project. Most importantly, the authors acknowledge the 249 women from the Chamorro community who generously gave of their time to help assess the health and well being of San Diego’s Chamorro community.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sadler, G.R., LaHousse, S.F., Riley, J. et al. Predictors of Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening among Chamorro Women in Southern California. J Canc Educ 25, 76–82 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-009-0016-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-009-0016-y