Abstract

Introduction

Sexualized violence is still a rather avoided topic in teaching at German universities, even though a remarkable proportion of the German population experienced child sexual abuse, including many in institutional settings (e.g., schools, clubs of leisure activities). This study examines the effectiveness of an interdisciplinary university curriculum about sexualized violence in educational and clinical institutions.

Methods

Students participated in seminars about sexualized violence, sexual socialization and education, and professionalism and ethics. In 2017/2018, n = 156 students assessed the curriculum before, immediately after and/or 6 months after participating. The assessment covers knowledge about and confidence in handling issues of sexualized violence and attitudes toward sex-related myths. The same questionnaires were used in a control group (n = 54).

Results

In the curriculum group, self-assessed and declarative knowledge improved, the students were more confident in their abilities to handle issues of sexualized violence in a professional way, and sex-related myths were rejected even more strongly after the curriculum.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that awareness and knowledge about sexualized violence in institutions can be increased and sustained through the use of the curriculum “Sexualized Violence in Institutions.” These encouraging results suggest that the curriculum should be taught in pedagogical and clinical disciplines at more universities.

Policy Implications

In view of the decentralized education system in Germany and the freedom of research and teaching at German universities, the curriculum can only be implemented on a voluntary basis. However, in terms of education policy, such an implementation could be supported by state-funded programs that provide lecturers both with necessary qualifications and necessary resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The probability is high that students who strive to work with children or juveniles (e.g., in schools, youth welfare, healthcare) will come into contact with individuals who are victims of child sexual abuse. An international meta-analysis shows lifetime prevalence rates for child sexual abuse including noncontact abuse as well as forced intercourse that vary from 8 to 31% for girls and from 3 to 17% for boys (Barth, Bermetz, Heim, Trelle, & Tonia, 2013). Although the occurrence of child sexual abuse is mostly associated with the private and family sphere, sexualized violence in institutional settings should not be underestimated. In Germany, a non-negligible proportion of the total population (about 5% of women and 1% of men) have experienced some form of sexual incident (including sexual harassment, sexual assault with and/or without penetration) in institutional settings, e.g., schools or clubs of leisure activities; one-half of the abusers were caregivers, while the other half were peers (Witt et al., 2018). A study of German elite athletes who had experienced sexualized violence showed that 10% of those affected were younger than 14 years of age at the time of their first experience and 57% were aged between 14 and 17 years. Most of the perpetrators were male adults who were looking after the athletes, e.g., coaches or physiotherapists (Ohlert, Seidler, Rau, Rulofs, & Allroggen, 2018). With regard to children living in German residential care facilities or boarding schools, 82% of girls and 37% of boys reported at least one sexual incident of any kind that occurred inside or outside the institutions (Allroggen, Rau, Ohlert, & Fegert, 2017).

Sexualized violence against children and adolescents is a phenomenon without temporal, spatial, or social boundaries and can arise under various institutional and organizational conditions. Böllert and Wazlawik (2014) therefore recommend extending the view beyond the organizational structures of the various institutions and striving for greater professionalization in dealing with sexualized violence. This underlines the importance of integrating the topic in university teaching to prepare future experts for this serious issue already during their academic training. However, child sexual abuse and sexualized violence are still rather avoided topics in teaching at German universities: in 2016/2017, less than half of the examined universities offering relevant courses of studies such as social work, educational sciences and (social) pedagogy explicitly taught prevention of sexualized violence and/or child welfare (Wazlawik & Kopp, 2018). The curriculum evaluated here, which was systematically developed and implemented at several universities, is the only one of its kind in Germany.

The Public Debate on Sexualized Violence in Germany Since 2010

When numerous cases of sexual child abuse at various boarding schools were disclosed in Germany in 2010, the protest of many victims and a broad public debate forced politicians to take action. Accordingly, the government implemented three political institutions to address and further examine the problem. The first was the round table committee “Child Sexual Abuse in Relationships of Dependence, and Imbalance of Power in Private and Public Institutions and Families,” which was chaired by three German Federal Ministries (Family Affairs, Justice, and Education and Research) and “whose task was to develop recommendations and strategies concerning support for victims, prevention of future abuse, education of professionals, and judicial questions” (Spröber et al., 2014). The second institution was the “Independent Commissioner for Child Sexual Abuse Issues” and the third one, implemented in 2016, was the “Independent Commission for the Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse.” The demand for increased research on the subject was also met relatively early in the debate. The German Federal Ministry of Education and Research [Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF] funded 23 research projects on sexualized violence in educational institutions. In this process, five junior professorships were implemented to address this subject. The five newly appointed junior professors at the universities of Hamburg, Münster, Kassel, Kiel, and Merseburg developed the interdisciplinary curriculum “Sexualized Violence in Institutions,” composed of three interrelated seminars. The purpose of this curriculum is to teach students basic knowledge about sexualized violence in educational institutions, sexual socialization and sex education, as well as the professional handling of these topics respecting ethical principles. Based on the assumption that knowledge, reflection, and attitudes form a basic component for professional handling of sexualized violence (Böllert, 2014), the curriculum is understood as a preventive intervention and security measure.

The Curriculum

Since 2017, the German universities of Hamburg, Kassel, Kiel, Merseburg, and Münster have offered three interrelated seminars on sexualized violence in educational and clinical institutions. This curriculum is aimed primarily at students studying subjects like educational science, social pedagogy, social work, psychology, or further teaching related social and humanistic science courses. The curriculum has a theoretical and empirically based framework. A multi-method concept was used to create lasting changes in the students’ attitudes and behavior; it was attempted to demonstrate the gap between the students’ current knowledge and behavior and the current state of scientific and pedagogical knowledge. Despite didactic formats, the curriculum also includes several active learning strategies. This concept engages students in structured practice, includes feedback to students, and provides chances to practice after receiving specific feedback. For example, the students have opportunities to practice intervention techniques and team communication through role plays focusing on challenging situations. Each seminar consists of 14 weekly sessions, whereby one seminar (Seminar C) was held as a block seminar on two weekends. In the following, each seminar is described shortly. For a more detailed description of the background, concept, teaching units, and literature basis, see Retkowski, Dekker, Henningsen, Voß, and Wazlawik (2019). Additional results of a qualitative evaluation of the students’ experiences and feedback on the curriculum are described by Schwerdt, Christmann, Stück, Dekker, and Wazlawik (2019).

Seminar A: Basic Knowledge About Sexualized Violence in Institutional Settings (Topic A)

The seminar aims to provide basic knowledge about sexualized violence in familial and institutional settings, the legal position, and the prevalence of child sexual abuse. Additionally, the seminar imparts knowledge about the effects on victims, the strategies of offenders, and the dynamics in educational institutions, as well as interventions and preventive strategies.

Seminar B: Sexual Socialization and Education (Topic B)

This seminar teaches theoretical approaches and empirical knowledge about issues of sexuality in individual, social, and professional terms. Furthermore, it is about power and structural violence. Examining sex-related topics and behaviors can be seen as key components of pedagogic and social work. Thus, the seminar aims to support the students’ extensive understanding of sexual development and relationships, provide basic knowledge about sex education, and improve the students’ communicative skills in handling these often tabooed and shamefaced topics.

Seminar C: Professionalism and Ethics (Topic C)

The seminar addresses the requirements and terms of a professional approach to issues of sexuality as well as sexualized violence in institutions. Furthermore, it focuses on a reflective confrontation with the specific demands of pedagogical professionalism. The seminar informs about interventions, communication, cooperation, and prevention in the context of this issue. The students learn how to orientate toward ethical principles while coping with situational challenges.

Study Aim

The aim of this study was to evaluate if the curriculum “Sexualized Violence in Institutions” enhances (1) the students’ self-assessments and (2) declarative knowledge about sexualized violence in institutions, (3) their professional confidence regarding the topics of sexualized violence, sexual socialization, and professionalism and ethics, and (4) if the curriculum affects the students’ attitudes towards child sexual abuse and sexual aggression in general.

Methods

Data Collection

In the winter semester 2017/2018, the three seminars of the curriculum were offered at the Institute for Sex Research, Sexual Medicine and Forensic Psychiatry of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf and at the Institute for Educational Science of the University of Münster. Participants of the curriculum were students of educational science, social work, social pedagogy, psychology, and further teaching related social and humanistic science courses. Since the seminars are currently not compulsory courses at the participating universities but were held as elective courses within the framework of existing degree programs all participants took part in the seminars voluntarily.

Although Seminar A is well suited as an introductory course for the entire curriculum, it could not be ensured that it would always be attended first. Against this background and for the reason of better comparability, the curriculum group includes participants who attended only one of the three seminars. Students who participated in more than one of the seminars of the curriculum were excluded from the analysis (see section Sample Description). The students were asked to participate in standardized evaluation assessments before the first lesson (pre), immediately after the last lesson (post), and about 6 months after the last lesson (follow-up). At the pre-testing, the questionnaires were handed out to the students personally (paper-pencil). Because some students missed the last sessions of the seminars, post-testing questionnaires were provided personally as well as online. The follow-up assessment only occurred online. To motivate as many students as possible, the follow-up testing was rewarded with a 5€ voucher for a large online retailer.

At the University of Münster, data were also collected in a control group. The control group includes only students who did not visit any of the relevant seminars in the semester of data collection. They received the same questionnaires as the curriculum group at the beginning (pre) and the end (post) of the semester (but not at the time point of follow-up testing). It is unknown whether the students of the control group had applied unsuccessfully for participating in the curriculum or not.

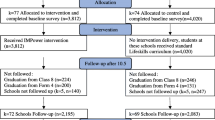

Sample Description

After the 3 evaluation assessments, 261 data sets from 222 students were available. Of these data sets; n = 51 data sets (20%) from 33 students were excluded from the analyses for different reasons: 12 students visited 2 seminars of the curriculum, and of those, 4 students also visited 1 or 2 control seminars; all existing data sets of these persons were excluded (n = 29). Sixteen students visited exactly one seminar of the curriculum but also one or more control seminars; the data sets of the control seminars were excluded (n = 17). Five students visited no seminar of the curriculum but two of the control seminars; the data sets with the most missings were excluded (n = 5). Thus, the total sample includes 210 students, 1 data set each.

Evaluation Methods

Table 1 shows example items of each of the measured variables described in detail below.

Knowledge and Confidence

The evaluation questionnaire contained 18 questions about self-assessed knowledge (SAK; scale from 1 = very good to 6 = very bad) to assess, how the students themselves perceive their level of knowledge. Of these questions, which were developed by the authors, six each were on topics of basics of sexualized violence in institutions (Topic A), sexual socialization and education (Topic B), and professionalism and ethics (Topic C). The separate scores of the topic-specific subscales were calculated using mean values. If more than one item remained unanswered, no mean value was calculated for the belonging subscale. If the values of all three topic-specific subscales were given, an average score for the total SAK was calculated.

Furthermore, 24 questions were included on declarative knowledge, i.e., factual knowledge about the topics dealt with in the seminar, (DK; single-choice format, maximum of 24 points in total) to assess the students’ knowledge of facts and terms. Of these questions, eight each are assigned to topics a, b, and c respectively (maximum of 8 points each). Missing values were counted as 0 points (wrong answer).

Four additional questions were about the students’ self-assessed professional confidence in handling issues concerning sexuality as well as sexualized violence in educational institutions (PC; scale from 1 = very good to 6 = very bad). Mean values were conducted when at least three answers were given.

Sex-Related Myths

Two scales were used to measure the extent to which the participants believe in sex-related myths. The Acceptance of Modern Myths about Sexual Aggression Scale (AMMSA-Scale) from Gerger, Kley, Bohner, and Siebler (2007) contains 11 items (scale from 1 = completely agree to 7 = completely disagree). The instrument has demonstrated high internal consistencies (Cronbachs α = 0.95) in German student populations (Gerger et al., 2007).

The Child Sexual Abuse Myths Scale (CSAM-Scale) from Collings (1997) measures the acceptance of Child Sexual Abuse Myths and stereotypes and contains 15 items (scale from 1 = completely agree to 5 = completely disagree). The CSAM scale yielded an acceptable internal consistency, Cronbach’s α = 0.76 (Collings, 1997).

For both scales, no mean values were conducted when more than 10% of the items were not answered (1 out of 11 items for AMMSA and 2 out of 15 items for CSAM). Examples are given in Table 1.

Statistical Analyses

Sample characteristics are given as absolute and relative frequencies, mean with standard deviation, or median with interquartile range (IQR), whichever is appropriate.

Impact of the Curriculum

To evaluate the impact of the curriculum on the students, the primary analyses focus on the curriculum group only, because the control group was solely evaluated at baseline and post intervention.

First, we investigated the difference to baseline at the post and follow-up testings (prescores minus post- or follow-up scores) in the variables SAK, DK, and PC. To meet the required model assumptions, the parameters of AMMSA and CSAM were transformed by calculating the logarithmized values (so the change to baseline is interpretable as a multiple of baseline). Each of the five outcome variables were analyzed separately starting with the same linear mixed model.

This linear mixed model included the seminar type (participating to seminars A, B, or C), the time indicator (post or follow-up), and the interaction between these two variables as fixed effects as well as the baseline value of the respective outcome. The students were considered as random effects to control for repeated measurement within each student. To simplify the linear mixed model, the interaction term and main effects were removed from the models when they did not explain significant additional variance in the outcomes using the likelihood-ratio test (backward elimination). The estimates of the resulting models are reported and visualized in figures representing the adjusted marginal means with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

In a second step, an analogous approach was used to analyze the three subscales of SAK and DK: sexualized violence (a), sexual socialization and education (b), and professionalism and ethics (c).

Curriculum vs. Control Group

To examine whether the expected changes in the curriculum group are due to participation in the seminar or due to pre-test sensitization, the curriculum group was compared to the control group at the post-testing. As in the first step, the five outcome variables were analyzed as change from baseline. A baseline adjusted linear regression with the group indicator was conducted.

All of the models present available case analyses. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant; nominal p-values are reported without correction for multiplicity. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA (Version 14.2, Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Sample Characteristics

The total sample includes data sets of n = 210 students. Of these students, n = 160 participated in the post-testing and n = 49 in the follow-up testing. About 29% of the students (n = 60) had visited lectures about sexualized violence before (curriculum group: n = 48 or 30%; control group: n = 12 or 22%).

Of the curriculum group, n = 156 students (90% female) took part in the pre-testing. On average, they were M = 23.05 years old (SD = 5.12, range = 17–50) and had been attending university M = 3.83 semesters (SD = 2.9, range = 1–23). Of these students, n = 86 (55%) also took part in the post-testing and n = 49 (31%) in the follow-up testing. The sample size including students who took part in all three testings was n = 33 students (21%).

Of the control group, n = 54 students (89% female) participated in the pre-testing. These students were M = 22.23 years old (SD = 2.8, range 19–31) and had been studying M = 4.66 semesters (SD = 1.62, range 2–12). Twenty students (37%) also participated in the post-testing. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics separated by groups.

Impact of the Curriculum

First, we examined the impact of Seminar (A, B, C) and Time (post, follow-up) on the change from baseline in the main outcome measures. For all participants of the curriculum group, estimated margins were conducted for self-assessed knowledge (SAK), declarative knowledge (DK), and professional confidence (PC); logarithmized values were conducted for Child Sexual Abuse Myths (CSAM) and Acceptance of Modern Myths about Sexual Aggression (AMMSA). For all variables despite DK, negative values express the students’ improvement on the scales. For the variable DK, positive values express an improvement on the scale.

SAK, DK, AMMSA, and CSAM revealed global effects. Neither significant interaction effects of Seminar and Time nor significant main effects were found (see Table 3). In detail, the SAK improved by 1.08 points, 95% CI [−1.19; −0.98], and p < 0.001. The DK increased by 1.07 points, 95% CI [0.58; 1.55], and p < 0.001. A global effect of the curriculum also revealed for the AMMSA scale, whereby the average answer was reduced by 12% (est. multiple of BL = 0.88, 95% CI [0.82; 0.94], p < 0.001), as well as for the CSAM scale, which was reduced by 8% (est. multiple of BL = 0.92, 95% CI [0.90; 0.95], p < 0.001). Thus, the students rejected sex-related myths even more after participating in the curriculum.

The analysis of the students’ PC shows a significant linear effect of Time on the difference to baseline. A post hoc contrast analysis reveals that the difference to baseline increased significantly from post to follow-up testing (est. diff. to BL = −0.20, 95% CI [−0.35, −0.05], p = 0.007).

Second, we examined the impact of Seminar (A, B, C) and Time (post, follow-up) on the subtopics a, b, and c. The analyses are separately reported for self-assessed knowledge (SAK; see Table 4) and declarative knowledge (DK; see Table 5).

Starting with the analyses of SAK, main effects of Seminar revealed for all three topics. In all three seminars, the students’ specific SAK about Topic A improved significantly, whereby a post hoc contrast analysis showed that Seminar A improved the SAK about Topic A more than Seminars B (est. diff. to BL = −0.35, 95% CI [−0.59, −0.1], p = 0.005) and C (est. diff. to BL = −0.27, 95% CI [−0.52, 0.02], p = 0.036). For Topic B, the analyses of the specific SAK not only revealed a significant main effect of Seminar but also of Time. Post hoc contrast analysis shows that Seminar B improved the SAK about Topic B more than Seminars A (est. diff. to BL = −0.84, 95% CI [−1.18, −0.51], p < 0.001) and C (est. diff. to BL = −0.83, 95% CI [−1.18, −0.48], p < 0.001). Furthermore, the difference to baseline at the follow-up testing was significantly greater than at post-testing (est. diff. to BL = −0.21, 95% CI [−0.40, −0.02], p = 0.032). For the specific SAK about Topic C, post hoc contrast analysis of the main effect of Seminar shows that Seminar C improved the specific SAK about Topic C more than Seminars A (est. diff. to BL = −0.49, 95% CI [−0.86, −0.13], p = 0.007) and B (est. diff. to BL = −0.83, 95% CI [−1.21, −0.46], p < 0.001). In summary, each of the seminars had the most impact on its main topic.

The analyses of DK only yielded main effects of Seminar for topics a and b (Table 5). The specific DK about Topic A improved significantly in Seminars A and C, but not in Seminar B. Post hoc contrast analysis shows that Seminar A improved the DK about Topic A more than Seminar B (est. diff. to BL = 0.72, 95% CI [0.19, 1.25], p = 0.007) but not more than Seminar C (est. diff. to BL = 0.36, 95% CI [−0.18, 0.89], p = 0.192). For DK about Topic B, solely Seminar B increased the DK significantly from baseline. Contrast analysis reveals that Seminar B improved the DK more than Seminars A (est. diff. to BL = 0.69, 95% CI [0.13, 1.24], p = 0.015) and C (est. diff. to BL = 0.75, 95% CI [0.17, 1.33], p = 0.011). For Topic C, a global effect over all seminars and time points improved the DK by 0.47 points, 95% CI [0.22; 0.74], and p < 0.001.

Curriculum vs. Control Group

The baseline adjusted linear regressions show that group affiliation is a significant predictor for changes in SAK (t(101) = −0.65, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.58) and PC (t(102) = −0.72, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.29), but not in DK (t(102) = 0.28, p = 0.617, R2 < 0.01). Regarding SAK, both groups showed significant differences to baseline, whereby the difference was greater in the curriculum than in the control group; regarding DK and PC, the differences to baseline were only significant in the curriculum group but not in the control group. Group affiliation neither predicted the multiple of baseline for AMMSA (t(100) = −0.03, p = 0.827, R2 < 0.01) nor for CSAM (t(100) = −0.09, p = 0.190, R2 = 0.02). For both AMMSA and CSAM, significant multiples of baseline only revealed in the curriculum group but not in the control group.

Discussion

The present study investigated the efficacy of an interdisciplinary curriculum about sexualized violence in educational and clinical institutions (see Retkowski et al., 2019) on the students’ self-assessed knowledge (SAK) and declarative knowledge (DK). Changes were investigated in the total outcome measures as well as in three topic-specific subscales: sexualized violence in institutions (Topic A), sexual socialization and sex education (Topic B), and professionalism and ethics (Topic C). Furthermore, the students’ professional confidence (PC) in handling topic-related issues as well as the students’ attitudes toward sex-related myths (measured by AMMSA and CSAM scales) were examined. We evaluated a curriculum that not only significantly improves the students’ SAK, DK, and PC but also enhances the rejection of sex-related myths after participation.

Regarding self-assessed knowledge, each seminar yielded significant changes from baseline in each subtopic. As anticipated, we found that each of the three seminars yielded the greatest impact on the difference to baseline in its main topic. For declarative knowledge, the results are also very satisfactory. As expected, Seminars A (basic knowledge about sexualized violence in institutional settings) and B (sexual socialization and sex education) achieved the greatest changes in their main topics; regarding Topic C, the impact of the three seminars does not differ. The main effect of time in the analysis of the professional confidence in handling topic-related issues indicates not only short-term but also long-term effects of the curriculum. Furthermore, after the completion of the curriculum, the students reject sex-related myths more strongly than before. These results are especially remarkable because both AMMSA and CSAM scales have strong ceiling effects and effect sizes of interventions are usually low (e.g., Verlinden, Scharmanski, Urbann, & Bienstein, 2016).

Given the fact that teaching about prevention of sexualized violence at universities is rather scarce (Wazlawik & Kopp, 2018), it comes as no surprise that only a relatively small amount of participants had visited lectures about sexualized violence before. It is all the more promising that the curriculum about this highly neglected topic results in long-term changes in the students’ self-assessed and declarative knowledge, professional confidence, and attitudes towards sex-related myths. The comparison of the curriculum and control group underlines the impact of participating in the curriculum. In the control group, solely the change from baseline in SAK was significant, which indicates a possible pre-test sensitization. In spite of the larger time gap between pre-, post-, and follow-up testing, this would mean that – regarding SAK – the intervention as well as simple pre-testing effects were strong enough to persist until assessed 6 (to 12) months not only after completing the curriculum but also after solely participating in the pre-testing. In the curriculum group, all changes from baseline/multiples of baseline were significant.

In addition to the quantitative approach of this study, the qualitative analyses of the evaluation of the curriculum also highlight that students consider the practical and applied orientation of the seminars to be highly relevant (Schwerdt et al., 2019). The success of the evaluated curriculum might be due to the fact that it allows for both teaching and learning on many levels. The curriculum aims to raise awareness of highly sensitive and, for some participants, emotionally stressful issues. Some students encounter topics of sexualized violence for the first time. For others, seminar contents may activate memories of their own victimization. Therefore, lecturers are prepared for problems that could arise and try to create a confidential atmosphere.

Due to the special multi-method structure of the curriculum (Retkowski et al., 2019), knowledge is imparted through the use of different teaching methods. The effectiveness of such multi-method teaching is supported at least for other fields of education, e.g., for behavioral changes in health care (for a comprehensive meta-analysis see Hauer, Carney, Chang, & Satterfield, 2012), for business studies (Ongeri, 2017), for political science studies (Lambach, 2017), and for higher education teaching in general (Metz-Göckel, Kamphans, & Scholkmann, 2012; Schneider & Mustafic, 2015).

The evaluated curriculum is not only based on current research findings but also on the cooperation with guest lecturers from professional practice. In this way, the students can learn from the experiences of the other participants and the experts and can explore and practice specific situations in dealing with sexualized violence, e.g., in role plays.

Against the background of the generally promising results, we would welcome it if the curriculum were offered and further developed at other universities. In view of the decentralized education system in Germany and the freedom of research and teaching at German universities, such an offer can only be implemented on a voluntary basis. However, in terms of education policy, such an implementation could be supported by state-funded programs that provide lecturers both with the necessary qualifications and the necessary resources to teach the seminars of the curriculum. A relevant institution in the implementation of such a project would be, for example, the Federal Centre for Health Education.

Limitations, Strengths, and Implications

This study has limitations that should be addressed by future research. First and foremost, we did not measure actual practice performance but changes in knowledge and attitudes. The central reason for this is feasibility: the majority of our students are not yet working practically, and it was not possible to measure behavioral changes during the project period. Methodologically, the question would also arise as to how preventive behavior in everyday working life could be measured at all. In a systematic review that focuses on research in the health education area, Hauer et al. (2012) found that lasting effects in health education are correlated with curricula that combine didactic and interactive teaching formats. We therefore believe that the improved knowledge and self-confidence of students in dealing with sexualized violence in educational institutions are linked to the diversified methodical character of the curriculum and can actually contribute to more effective protective actions. This assumption is supported by findings from the qualitative approach of evaluating the curriculum where students pointed out their overall appreciation of the didactical set-up (Schwerdt et al., 2019). Nevertheless, further studies measuring actual performance in a practical pedagogical environment would be highly desirable. Another problem arising from the time limitation of our study is the comparatively short follow-up period. It would be preferable if the post-measurement was much closer to the beginning of the students’ working lives. In methodological terms, however, as this would probably result in a significantly higher dropout rate, our approach was chosen as a compromise.

Another limitation of our study is the fact that we have assessed students who have chosen to attend the courses voluntarily. It cannot be ruled out that a compulsory curriculum would have led to weaker results for less motivated students. Another criticism can be made of the non-randomized recruitment of our control group. It cannot be ruled out that the post-test differences between the curriculum and control group may be due to characteristic differences between the groups rather than to the intervention. This decision was also made primarily for reasons of feasibility. Nevertheless, this design also allows a higher degree of external validity, because it involves intact groups (i.e., students can participate in the seminar they wish to attend).

With regard to our statistical analyses, multiple imputations were not possible because we had no auxiliary variables. Therefore, we decided to calculate available cases analyses. Nevertheless, the low response rate from pre to post or follow-up (caused by non-participation) can be considered a weakness as it may have led to a selection bias: those students who have increased their knowledge and confidence about sexualized violence in institutions may have been more likely to stay in the seminar and participate in the further assessments. By contrast, the low response rate results in a higher chance of type II error. Future research should try to enhance the students’ motivation to participate in all planned testings. This would be easier to achieve if the curriculum were offered and evaluated as a compulsory course.

The present study also points to a number of strengths we would like to underline. First, to evaluate the effects of the intervention independent of the effects of pretesting, we used the repeated measure design, where we rigorously used the same questionnaire not only in the curriculum but also in a control group. Some of our results indicate pre-test sensitization. Thus, future research should pay more attention to the impact of its presence to make researchers more aware of the subtle impact of pre-test sensitization. Second, the two post-test assessments allow an examination of those aspects of the curriculum that differentiate short- and long-term effects among the students. Third, the examinations of the different seminars and therefore specific teaching topics were conducted to determine which aspects of the curriculum are most likely to lead to changes in self-assessed knowledge and declarative knowledge. Fourth, data was collected at two universities to enhance the generalizability of the present results.

The results of the current study support advocates of higher education on sexualized violence. Universities that are looking for effective ways to provide knowledge about sexualized violence can benefit from the introduction of the curriculum “Sexualized Violence in Institutions” (Retkowski et al., 2019), which was evaluated here for the first time.

References

Allroggen, M., Rau, T., Ohlert, J., & Fegert, J. M. (2017). Lifetime prevalence and incidence of sexual victimization of adolescents in institutional care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 66, 23–30.

Barth, J., Bermetz, L., Heim, E., Trelle, S., & Tonia, T. (2013). The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Health, 58, 469–483.

Böllert, K. (2014). Sexualisierte Gewalt. Professionelle Herausforderungen [sexualized violence. Professional challenges.]. In K. Böllert & M. Wazlawik (Eds.), Sexualisierte Gewalt. Institutionelle und professionelle Herausforderungen [sexualized violence. Institutional and professional challenges] (pp. 139–150). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Böllert, K., & Wazlawik, M. (2014). Pädagogische Professionalität und sexuelle Gewalt in der kinder- und Jugendhilfe – von der Institutionen- zur Professionsperspektive. [pedagogical professionalism and sexual violence in child and youth welfare - from the institutional to the professional perspective]. Forum Jugendhilfe, 62(1), 24–29.

Collings, S. J. (1997). Development, reliability, and validity of the child sexual abuse myth scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12, 665–674.

Gerger, H., Kley, H., Bohner, G., & Siebler, F. (2007). The acceptance of modern myths about sexual aggression scale. Development and validation in German and English. Aggressive Behavior, 33, 422–440.

Hauer, K. E., Carney, P. A., Chang, A., & Satterfield, J. (2012). Behavior change counseling curricula for medical trainees: A systematic review. Academic Medicine, 87(7), 956.

Lambach, D. (2017). Alte Ziele, neue Methoden: Aktives Lernen als Mittel zur Demokratieerziehung in der politikwissenschaftlichen Hochschullehre [Old goals, new methods: Active Learning as a Means for Democracy Education in Political Science Higher Education]. Zeitschrift für Politikberatung, 64(4), 437–453.

Metz-Göckel, S., Kamphans, M., & Scholkmann, A. (2012). Gute Lehre – Empirisch geprüft [good teaching - empirically tested]. Das Hochschulwesen, 60(6), 174–181.

Ohlert, J., Seidler, C., Rau, T., Rulofs, B., & Allroggen, M. (2018). Sexual violence in organized sport in Germany. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 48(1), 59–68.

Ongeri, J. D. (2017). Instruction of economics at higher education: A literature review of the unchanging method of “talk and chalk”. International Journal of Management Education, 15(2), 30–35.

Retkowski, A., Dekker, A., Henningsen, A., Voß, H.-J., & Wazlawik, M. (2019). Basis-Curriculum zur Verankerung des Themas, Sexuelle Gewalt in Institutionen “in universitärer und hochschulischer Lehre [Basic Curriculum for Establishing the Issue of “Sexual Violence in Institutions” in University Teaching]”. In M. Wazlawik, H.-J. Voß, A. Retkowski, A. Henningsen, & A. Dekker (Eds.), Sexuelle Gewalt in pädagogischen Kontexten [Sexual Violence in Pedagogical Contexts] (pp. 261–290). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Schneider, M., & Mustafic, M. (2015). Gute Hochschullehre: Eine evidenzbasierte Orientierungshilfe [Good University teaching: An evidence-based orientation guide]. Berlin: Springer.

Schwerdt, D., Christmann, B., Stück, E., Dekker, A., & Wazlawik, M. (2019). Sexualisierte Gewalt als Thema der Hochschullehre – Entwicklung und Erprobung eines interdisziplinären didaktischen Moduls [sexualized violence as a subject of university teaching - development and testing of an interdisciplinary didactic module]. Kindesmisshandlung und -vernachlässigung, 22(2), 212–223.

Spröber, N., Schneider, T., Rassenhofer, M., Seitz, A., Liebhardt, H., Königm, L., & Fegert, J. M. (2014). Child sexual abuse in religiously affiliated and secular institutions: A retrospective descriptive analysis of data provided by victims in a government-sponsored reappraisal program in Germany. BMC Public Health, 14, 282.

Verlinden, K., Scharmanski, S., Urbann, K., & Bienstein, P. (2016). Preventing sexual abuse of children and adolescents with disabilities – Evaluation results of a prevention training for university students. International Journal of Technology and Inclusive Education, 5, 859–867.

Wazlawik, M., & Kopp, K. (2018). Neue Kollegin, neuer Kollege – der Schutz des Kindes als Thema im Studium [new colleague - child protection as a topic in university studies]. In M. Böwer & J. Kotthaus (Eds.), Praxisbuch Kinderschutz – Professionelle Herausforderungen bewältigen [practice book child protection - coping with professional challenges] (pp. 410–421). Weinheim/München: Beltz Juventa.

Witt, A., Rassenhofer, M., Allroggen, M., Brähler, E., Plener, P. L., & Fegert, J. M. (2018). The prevalence of sexual abuse in Institutions: Results From a Representative Population-Based Sample in Germany. Sexual Abuse. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063218759323.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. The development of the university curriculum “Sexualized Violence in Institutions” was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). The evaluation of the curriculum presented in this article was funded by the German Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women, and Youth (BMFSFJ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the ethics committee of the German Educational Research Association (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Erziehungswissenschaft, DGfE). All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stück, E., Wazlawik, M., Stehr, J. et al. Teaching About Sexualized Violence in Educational and Clinical Institutions: Evaluation of an Interdisciplinary University Curriculum. Sex Res Soc Policy 17, 700–710 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00427-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00427-8