Abstract

One of the most important transitions of China from a centrally planned economy to a market-based economy was the emergence of entrepreneurship in two different forms of private enterprise, viz., getihu and siyingqiye. Getihu firms are legally restricted to a household ownership structure and a firm size upper limit. Siyingqiye firms do not face these restrictions but are more costly to set up. Using a unique database for 31 Chinese regions over the period 1997–2009, we investigate the economic antecedents of regional rates of getihu and siyingqiye, and to what extent these antecedents are in line with the “entrepreneurial” or the “managed” economy as per Audretsch and Thurik (Audretsch and Thurik, Journal of Evolutionary Economics 10:17–34, 2000, Audretsch and Thurik, Industrial and Corporate Change 10:267–315, 2001). We find that particularly the antecedents of regional siyingqiye rates are in line with the “entrepreneurial” economy in the sense that regional economies that are more conducive to knowledge production and knowledge spillovers have higher rates of siyingqiye firms. Overall, our analysis suggests that both types of entrepreneurship play important but distinct roles in stimulating China’s economic development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Chinese economy has gone through major transitions in the last three decades, where a substantial part of economic activity has shifted from state-owned sectors to private sectors. With a population of more than 1.3 billion people and a labor force of more than 800 million, the economic potential of China remains huge. Two developments characterize China’s economic transition. First, China has transitioned from a tightly centrally planned economy to a market-oriented economy but still shaped by the government’s long-term economic development plan and entrepreneurship focus (cf. Huang, 2010; Oi, 1995). Policies have helped speed up China’s economic development by making important adjustments in the areas of education, national innovation system, economic openness, market function, infrastructure investment, etc. (Ramesh, 2020). This transition cycle has run for more than three decades and still plays a critical role in China’s economic growth. One important characteristic of this economic and institutional transition is the attitude transition in acknowledging entrepreneurship as a legitimate economic activity.

With regard to this attitude transition, one has to bear in mind that China’s history and culture have heavily influenced Chinese attitudes towards entrepreneurial activity. Regarding China’s history, after the Second World War, China developed a communist political and economic system in which all property is owned by the community and each person contributes and receives according to their ability and needs, and where the no-profit-purpose forms the ideological foundation. Entrepreneurial activity, in which private property and profits are key, does not fit within this system, and was thus viewed with suspicion. The above-mentioned transition to a market-oriented economy has greatly relaxed the conditions for entrepreneurial activity in China but still, the suspicious attitude towards entrepreneurial activity among the population had to be overcome as well, that is, an attitude transition towards entrepreneurial activity was necessary. On the other hand, regarding Chinese business culture, Chinese businessmen tend to have a greater risk appetite compared to their western counterparts (Zhang et al., 2015). The Chinese are also more flexible and their business approach is less formalized. Finally, due to the higher power distance in Chinese culture, Chinese businesses have a more hierarchical governance structure facilitating a fast decision-making process (Zhang et al., 2015). These characteristics of Chinese businessmen and businesses are highly conducive to entrepreneurship. In summary, whereas Chinese history of a communist system impeded entrepreneurship at least until the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, Chinese business culture is more conducive to entrepreneurship (Ramesh, 2020).

The second development characterizing China’s recent economic transition has been the transition from a factor-driven economy to an efficiency-driven economy in the past few decades, and China’s current ambition to transition towards an innovation-driven stage (Kowalski, 2021).Footnote 1 This ambition is very much echoed by China’s recent national economic development strategy of “Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation”Footnote 2 to encourage and provide a better environment for Chinese people in starting entrepreneurial activities and pursuing innovation at established firms, so as to foster entrepreneurship and innovation as the new engines of economic growth. Indeed, the developments towards a market-oriented economy and towards an innovation-driven economy, described above, are not independent from each other with entrepreneurship undoubtedly contributing to China’s fascinating economic growth (He et al., 2019).

In the present paper, by studying two types of private firms prevalent in China’s regional economies—getihu and siyingqiye—, and applying econometric analysis to a unique data base for Chinese regions, we investigate the progress of China’s relatively young entrepreneurial sector in the transition process towards a market-oriented, innovation-driven economy.

Getihu (in Chinese) are private businesses with a maximum of seven employees. Siyingqiye (in Chinese) are private businesses with more than seven employees. Besides the difference in the maximum number of employees, there are also some other important differences between getihu and siyingqiye. In particular, getihu are restricted to only use individual or household assets for running their firm but they register with a shorter and easier start-up procedure. In contrast, siyingqiye are given much more relaxed conditions in terms of more allowed sources of registered capital (i.e., shareholders can be from outside of the entrepreneur’s family), but are compulsory required to hold a fixed amount of registration capital, causing higher start-up costs. For these differences, getihu are usually smaller than siyingqiye in terms of organizational size. In western terms, getihu are more like sole proprietorships while siyingqiye are more like limited liability companies, by and large.

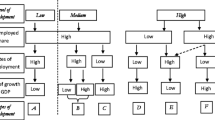

A plethora of studies have been focusing on China’s economic and institutional transition (e.g., Ahlstrom & Bruton, 2002; Anderson et al., 2003; Batjargal and Liu 2004; Begley et al., 2005; Davies & Walters, 2004; George & Prabhu, 2000; Lau & Busenitz, 2001). Within this plethora, two main streams of research may be distinguished. The first stream focuses on China’s institutional background and studies the institutional environment and entrepreneurship in China either separately or in direct relation to each other (Qian, 2000; Yang & Li, 2008; Zhou, 2014). However, this stream overlooks the aggregate indirect impact of economic institutional transition on entrepreneurship development, i.e., through shaping economic antecedents of entrepreneurship such as economic openness, human capital, and institutional market changes (see also Fig. 1 in our “Theory” section).

The second stream of research statistically examines the impact of specific economic factors (such as FDI, the cost of labor, social capital, and industrialization) on China’s economic performance, either at the micro or macro level (Buckley et al., 2007; Chuang & Hsu, 2004; Li & Atuahene-Gima, 2001; Lin & Germain, 2003; Madariaga & Poncet, 2007; Xing, 2010). These studies focus on determining if there is a direct link between economic antecedents and economic development, but overlook the intermediate mechanism of entrepreneurship, where not only the number of private firms but also the quality of the private firm sector play their own important roles in China’s economic development.

This study is positioned at the intersection of the above two streams of research and aims to address the crucial link between economic antecedents and private firm rates in Chinese regions, in order to offer a better understanding on the nature (in terms of both quality and quantity) of entrepreneurship in China. Our analysis helps predict to what extent increasing numbers of private firms may contribute to economic development, taking into account that not only the quantity but also the quality of a region’s private firm population determines the economic impact of entrepreneurship (Thurik et al., 2013).

In order to shed light on the quality of a region’s entrepreneurship population, we argue there is a missing link in the economic mechanism of China’s entrepreneurship and economic development: the economic antecedents of private firm rates in Chinese regions. Distinguishing between two different types of private firms (getihu versus siyingqiye), we investigate the following main research question: to what extent are regional private firm rates sourced from “productive” antecedents, i.e., antecedents which are in accordance with a modern, innovation-driven (“entrepreneurial”) type of economy (Audretsch and Thurik, 2000, 2001, 2004; Thurik et al., 2013), where comparative advantage is no longer based on exploitation of scale economies (as in the efficiency-driven economy), but rather on the ability to generate and commercialize new knowledge (Porter et al., 2002; Audretsch and Thurik, 2001)? From the perception of the economic consequences of entrepreneurship development, establishing the economic antecedents of private firm rates then enables us to reflect on the extent to which entrepreneurship development in China has been up to speed with transitioning to the innovation-driven stage of economic development. In particular, different antecedents will be associated with different types of entrepreneurship and different roles played in the economy. Empirically, these antecedents will be established by using a unique data base for Chinese regions, and applying econometric analysis to quantify the impact of regional conditions on the regional rates of getihu and siyingqiye. In the same spirit, we also examine to what extent interactions between the numbers of getihu and siyingqiye types of private firms are in line with an “entrepreneurial” type of economy? (secondary research question).

In terms of the title of our paper, by studying regional antecedents of getihu and siyingqiye and their mutual interactions, we aim at drawing conclusions as to which type of private firm should take the lead (“run ahead”) in transitioning China towards the innovation-driven stage of economic development, where knowledge-based entrepreneurial activity is key.

By investigating regional-level determinants of entrepreneurship in China, our study contributes to extant literature in at least three ways. First and as already mentioned, the antecedents of Chinese economic development (e.g., FDI, labor costs, etc.) have often been studied quantitatively; however, the intermediate mechanism of entrepreneurship influencing economic development has been overlooked. This study therefore contributes by looking at the role of economic antecedents in shaping entrepreneurship development (see also Fig. 1 in our “Theory” section).

Second, as far as research on entrepreneurship is concerned, we move analysis of entrepreneurship during economic transition in China beyond qualitative evidence (case studies and descriptive statistics) of how entrepreneurs adapt to changing economic circumstances. We apply econometric analysis to quantify the impact of regional conditions on the rates of two types of private firms in regional economies. Regional antecedents of Chinese firm rates have been rarely explored, let alone the antecedents of the two main different types of private firms (Yang & Li, 2008).

Third, by applying a simulation analysis, we are able to shed light on the size and magnitude of the mutual interaction between getihu firms and siyingqiye firms in Chinese regions. This, in turn, gives us an indication to what extent these types of firms are able to stimulate and challenge each other in the current Chinese economy.

The paper is organized as follows. After reviewing the evolution of China’s institutional environment and corresponding private firm development since the 1980s, our “Theory” section addresses the conceptual framework of this study. This section also briefly describes how economic antecedents may be different in the “managed” versus the “entrepreneurial” economy (Audretsch and Thurik, 2001). Based on our “Theory” section, we then develop our hypotheses. Next, we describe our data, model set-up, and methodology. In the final sections, we present and discuss our results and conclusions.

Historical Background of Chinese Entrepreneurship

In a transition context, a successful entrepreneurial economy depends not only on the initial conditions in the transition economy but also on the speed and consistency with which the reform process is applied (Estrin et al., 2006). In the last three decades, China has attempted an entrepreneurial approach in the economic transition from a central-planning system to a market-based economy. The major characteristics of China’s institutional environment, especially formal institutions since the 1950s, comprise the one party state and strong government intervention (Barkema et al., 2015). Although the Chinese government has been relaxing the impact of state control on market and business, policy-driven economic transition still cannot be denied as the major cause of China’s entrepreneurship development via the shaping of economic antecedents. These antecedents have been considered as the key factors in promoting efficient social reforms and economic development (World Bank, 1993), efficiently bringing Chinese society restrictive covenants (Stiglitz & Yusuf, 2001).

Since the late 1970s, Chinese entrepreneurship has experienced three generations of organizational forms: commune and brigade enterprises, township and village enterprises (TVE), and finally, getihu and siyingqiye. Commune and brigade enterprises were the first generation, born in the 1980s, designed by the central government to deal with the bad economic consequences caused by China’s Cultural Revolution (1966 to 1976), particularly in nonagricultural industries (Gregory et al., 2000). This organizational form did not function in Chinese economy longer than a decade and was then replaced by the second generation, TVEs, characterized by shared ownership of local government and collectives. Similar to the first generation, TVEs faced tremendous questioning on its ownership and the nature as private firms. Though it contributed significantly to China’s economy in the late 1980s (20% of China’s gross output; Liao & Sohmen, 2001), TVEs were terminated by gradually being replaced by the third generation of organizational forms from the late 1980s: getihu and siyingqiye.

As mentioned earlier, getihu are private businesses that are registered at the Chinese Industry and Commerce Office in the enterprise category with no more than seven people hired as employees.Footnote 3 In June 1988, the Chinese central government issued the tentative stipulations on private enterprise (TSPE), stipulating that a unit with privately owned assets and more than seven employees could be registered as another form of private enterprise named siyingqiye. Although siyingqiye have more potential for expansion, getihu tend to have a wider cognitive acceptance.Footnote 4

Introducing getihu and siyingqiye as new organizational forms of private firms was a landmark for China’s economic transition, and very critical in China’s entrepreneurship development. Since then, private firms have started coexisting with state-owned enterprises (SOEs), though they only played a marginal, stop-gap role in the economy in the early 1990s (Gregory et al., 2000). However, given China’s policy-driven economic transition, the early stage of governments’ discriminative attitude to private sectors hampered Chinese entrepreneurs’ contribution due to a lack of acknowledgement, resources, and development space. In 1989 and 1990, China’s economic growth rate slowed to 4.4% and 3.9%, respectively.

In 1992, Deng Xiaoping’s South Touring Talk changed Chinese entrepreneurs’ situation. Deng’s suggestion of transforming China into an economically strong country through entrepreneurial activities has guided Chinese government to re-set the goal of economic reform to transit China into a socialist market economy (announced at The Chinese Fourteenth Party Congress in September 1992) on the foundations of entrepreneurship. A series of reforms was executed, such as reducing state intervention to state-owned companies, “selling off small ones” (Young, 1995), and “grasping the large” (zhuada fangxiao in Chinese, meaning saving the larger SOEs and letting smaller SOEs exit or be acquired).Footnote 5 Other new policies included the fields of foreign exchange, taxes, monetary and fiscal system, and streamlining government bureaucracy (Qian, 2000). By 1996, these reforms had triggered a second boom in entrepreneurial activities, following 50 to 70% of the SOEs being privatized.

In the late 1990s, China’s entrepreneurship development entered a new era. By 1998, getihu and siyingqiye together accounted for one-third of national industrial output and one-fifth of national non-farm employment (Gregory et al., 2000). Chinese government started to clarify the importance of entrepreneurship in China’s economy. In 1999, the Second Plenary of the Ninth People’s Congress gave the private sector the same legal footing as the public sector, remarked as the central government’s formally granting private sectors constitutional recognition (Zhou, 2014).

This governmental attitude change is also echoed by Chinese governmental de-centralization reform in the late 1990s, by which regional governments have relatively independent authority to determine the structure of regional expenditure (Qian, 2000), issuing business license, coordinating business development, resulting business disputes, and enacting tax policies (Zhou, 2014). Therefore, each provincial government had to figure out which regulatory policies were most appropriate for their own region, or imitate successful policies in other regions (Breznitz & Murphree, 2011). Partly as a result of differences in regional policies, there is considerable variation in regional rates of getihu and siyingqiye.

To summarize, since the end of the 1990s private firms in the forms of getihu and siyingqiye account for ever increasing shares of China’s GDP, and there is considerable variation, both over time and across regions, in the relative prevalence of these two types of private firms. This variation will be exploited in the empirical analysis, where economic antecedents of getihu and siyingqiye rates will be emphasized.

The Role of Women in China’s Entrepreneurship Development

In our historical overview of Chinese entrepreneurship, the role of women should not go unmentioned. The number of women entrepreneurs in China has been growing continuously since the 1980s (Cooke & Xiao, 2021). China’s progress in improving women’s career identity and gender equality is remarkable, compared to other countries with similar economic development levels. Since the 1950s when China started to be one of the communist countries, women were named as “half of the sky” in media and public, in order to signify the importance of women in social development and economic activities. According to UNDP (n.d.), 43.7% of China’s current labor force are women, and 76% of adult women have reached at least secondary level of education versus 83.3% of men. In addition, China’s Human Development Index (HDI) value increased by 52.5% from 0.499 (low) in 1990 to 0.761 (high) in 2019 (only one of five countries had moved from “low” to “high” on the index during this period). Similarly, the HDI values for Chinese women in gender equality and women’s empowerment (GEWE) had increased from 0.522 in 1995 to 0.744 in 2020, with China’s Gender Development Index (GDI) value equaling 0.957, an increase from 0.912 in 1995. This increase indicates the gaps between women and men in China are narrowing in education, health, and command over economic resources (UNDP, n.d.).

Moreover, since the 1980s, after private ownership (entrepreneurship) was acknowledged, the trend of women in joining entrepreneurial activities has been very positive, both in numbers and in depth. Even though the total number of female entrepreneurs is still far lower compared to males, Chinese female entrepreneurs’ achievement and success in wealth has been surpassing all other countries worldwide by 2021. According to the Hurun Wealth Ranking 2022 (Hurun Report, n.d.), which ranks the world’s female entrepreneurs who created their wealth from scratch and achieved a wealth value above 1 billion USD, the world top five female entrepreneurs are all from China. Moreover, the total number of Chinese female entrepreneurs whose wealth value exceeds 1 billion USD is 78, two third of the total number of successful female entrepreneurs in the world and three times the number from the United States (25).

Theory

Conceptual Framework: The Role of Entrepreneurship in Modern China

Current literature on China’s strong economic growth in recent decades has not taken into account the bigger picture of China’s entrepreneurship and economic development so that current knowledge about the role of entrepreneurship in China’s economic development has been partial in nature. Figure 1 exhibits our view on the bigger picture of the economic mechanism of China’s entrepreneurship and economic development. Since 1978, Chinese government has been gradually experimenting various transitional policies, which led to improvement of welfare (the standard of living) for the majority of the population (direct link between the most left and most right boxes in Fig. 1), but also to entrepreneurial activities being promoted in two ways. First, directly, by allowing and acknowledging the important role of private enterprise in the Chinese economy (arrow 1 in Fig. 1), which contributed to an increase in the numbers of private firms. Second, by improving the conditions for entrepreneurship, such as the renovation of labor, attracting foreign investment, facilitating urbanization, investing in knowledge stock and human resource development, and upgrading the institutional environment,Footnote 6 entrepreneurial activities may be boosted as well (see arrow 2 in Fig. 1).

In this study, we address the link between economic antecedents and private firm rates in Chinese regions (arrow 2 in Fig. 1). This link is crucial to understand the nature (in terms of quality) of entrepreneurship in China. In particular, while it is clear that the number of private firms has increased considerably over the last two decades, it is not clear to what extent these increased numbers may contribute to economic development (arrow 3 in Fig. 1), because higher numbers of private firms do not necessarily spur economic development (Van Praag and van Stel 2013; Shane, 2009). The economic contribution of entrepreneurship has been found to differ across different types of firms (e.g., ambitious vs. non-ambitious, opportunity vs. necessity-based), and hence the economic impact of entrepreneurship will not only be determined by the quantity but also by the quality of a region’s private firm population (Thurik et al., 2013).

In order to shed light on the quality of a region’s entrepreneurship population, we focus on the economic antecedents of (two types of) private firm rates in Chinese regions. In particular, we investigate to what extent regional private firm rates are sourced from “productive” antecedents like, for instance, a high education level of the regional population. Hence, by studying the crucial link between economic antecedents and private firm rates, we are able to understand the role of China’s macro-economic and economic institutional transition in shaping Chinese private firms’ development, not only directly in terms of facilitating higher numbers of private firms (arrow 1 in Fig. 1), but also in terms of shaping the right antecedents of entrepreneurship, influencing the type (quality) of entrepreneurship, and specifically uncover the economic antecedents of China’s two organizational forms of private firms: getihu and siyingqiye.

We will select economic antecedents from the literature on regional determinants of entrepreneurship (e.g., Reynolds et al., 1994) and empirically test to what extent economic antecedents of regional private firm rates are in line with the theory of the “entrepreneurial economy” (Audretsch and Thurik 2000, 2001, 2004; Thurik et al., 2013). This theory, discussed in more detail later on, describes how entrepreneurship contributes to macro-economic development in the innovation-driven stage of economic development, and which factors (antecedents) determine productive entrepreneurship (Baumol, 1990). This theory is particularly relevant for entrepreneurship development in China, which is moving from an efficiency-driven economy towards the innovation-driven stage (Fu, 2015; Fu and Mu 2014) with a number of regions taking the lead, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen.Footnote 7 If economic antecedents of regional private firm rates in China are in line with those described in the theory of the “entrepreneurial economy,” it may be expected that the economy has the right incentive structure in place to produce high quality entrepreneurship, and hence, that the entrepreneurial sector (private firm population) contributes substantially to economic development.

Rather than attempting to establish a direct link between entrepreneurship development and economic development (arrow 3 in Fig. 1), which is hampered by the complexity of incorporating entrepreneurship in formal models of economic theory and endogenous growth (Baumol, 1968; Carree and Thurik 2010), we take a more indirect approach by studying economic antecedents of entrepreneurship (arrow 2 in Fig. 1). As far as we are aware of, this is one of the first (if not, the first) studies on economic antecedents of regional rates of entrepreneurship in China, providing a better understanding of the complex role of entrepreneurship in China’s economic development. From the perception of the economic consequences of entrepreneurship development (arrow 3 in Fig. 1), this then enables us to reflect on the extent to which entrepreneurship development in China has been up to speed with transitioning to the innovation-driven stage of economic development.

From a Managed to an Entrepreneurial Economy

China’s current transition from an efficiency-driven stage to an innovation-driven stage of economic development requires a different way of organizing economic activity. In particular, in the efficiency-driven stage, comparative advantage is realized by an efficient use of physical capital which facilitates exploitation of scale economies. This exploitation typically takes place in an environment where the value of new ideas is relatively certain, so that economies of scale can also be achieved in the research and development sector. The most profitable firms in such an economy are typically large firms which can be relatively easy to maintain high profit levels. These are the characteristics of the so-called managed economy (Audretsch and Thurik 2001). In contrast, in the “entrepreneurial” economy, small and new firms play an important role, introducing new products and services in highly uncertain economic environments while quickly adapting to rapidly changing consumer preferences. In this type of economy, knowledge is a crucially important factor of production and the prime source of competitive advantage. Economic, and particularly, innovative activity by a heterogeneous population of firms is required for an innovation-driven economy (or “entrepreneurial” economy) to be competitive. In the entrepreneurial economy, competitive advantage of firms is based on new knowledge that, as a result of globalization and fast and expanding ICT developments, is highly uncertain in nature. This uncertainty causes the success of introducing new products or services to be less predictable than in the managed economy. A firm may only experience the economic value of his idea once it introduces the idea to the market (passive learning). At the macro-level, the market will select the best firms with the economically most valuable new product ideas. These firms will grow whereas the less innovative firms will decline and eventually exit (Jovanovic, 1982).

In this environment, where scale economies are relatively less important and flexibility more important, smaller firms are relatively better equipped to compete, and strong firm performance is generally less persistent as competition is stronger. These are the characteristics of the “entrepreneurial” economy (e.g., Audretsch and Thurik 2001). In such an environment, entrepreneurs with higher human capital levels tend to select into entrepreneurship, as higher skills are required to compete in the market (Van Stel et al., 2014).

Derivation of Hypotheses

We will derive hypotheses from the regional determinants of entrepreneurship literature (e.g., Armington & Acs, 2002; Reynolds et al., 1994). In this literature, determinants of entrepreneurship at the regional level are typically classified in three categories (Bosma et al., 2008): (i) demand and supply factors for entrepreneurship, (ii) agglomeration effects, and (iii) cultural or policy environment determinants. Regional demand for entrepreneurship relates to conditions for local consumer demand. For instance, higher average incomes in a region imply that consumers have more money to spend, and hence there is more room (“demand”) for entrepreneurship. On the other hand, a region with relatively highly educated inhabitants may produce relatively many individuals with the right skills for entrepreneurship (“supply” of entrepreneurship). We include in our study the main demand and supply side variables of regional entrepreneurship, including industrial structure (demand side), the stock of human capital (supply side), and the average wage rate, which has features of both the demand and the supply side. Importantly, as the composite pattern of these demand and supply side factors is for a big part reflected by the regional level of economic development (Wennekers et al., 2010), we do not use regional GDP per capita in our regression models, but rather the underlying demand and supply side factors.Footnote 8

Furthermore, we also include explicit measures of agglomeration effects and regional policy (such as the institutional environment) as well as two variables which are particularly relevant for regional entrepreneurship in the Chinese context, i.e., inward FDI and investments by state-owned enterprises, both of which may be classified on the demand side of entrepreneurship. But we will start our derivation of hypotheses with the interaction between the numbers of getihu and the number of siyingqiye.

Interaction Between Getihu and Siyingqiye

Our first hypothesis relates to the interaction between getihu and siyingqiye firms. Although getihu has a longer history than siyingqiye and are chosen by entrepreneurs in larger numbers, getihu and siyingqiye may benefit from each other’s presence, in part because of knowledge spillovers flowing between both types of firms. First, in China’s contemporary economy, getihu and siyingqiye play different roles in the value chain, where, in certain sectors such as retail, construction, and trading service, (larger) siyingqiye firms often act as demanders of specialized, high-quality, intermediate goods and services, while getihu, because of their specialized activity and size, often act as suppliers.Footnote 9 In such type of transactions involving high-tech goods, firms benefit and learn from each other’s knowledge (knowledge spillovers between getihu and siyingqiye). Hence, a stronger presence of siyingqiye in a region may create more demand for intermediate goods and services, allowing more room for specialized getihu firms in the market. This suggests a positive effect of the number of siyingqiye on the number of getihu.

-

Hypothesis 1a: The rate of siyingqiye firms has a positive impact on the rate of getihu firms.

Second, in an “entrepreneurial” economy, one may expect a continuous battle between small, innovative firms, a proportion of which may be expected to have the lower-cost getihu organizational form, at least until it is clear that the firm will be successful and grow beyond the seven employees limit. Thus, although getihu have smaller innovative capacity because of their size limit, the most viable firms with the best product ideas will grow out to larger size, and hence transition to the siyingqiye organizational form. The more (high-quality) getihu there are in an economy, the more competitive this evolutionary process will be, and the larger the chance that the “winners” from this process will grow bigger to siyingqiye firms. This suggests a positive impact of the number of getihu on the number of siyingqiye.

-

Hypothesis 1b: The rate of getihu firms has a positive impact on the rate of siyingqiye firms.

Both processes described above reflect how interactions including knowledge spillovers between getihu and siyingqiye firms contribute to the entrepreneurial ecosystem’s vibrancy and resilience. Importantly, for both processes, substantial interaction (including knowledge spillovers) between getihu and siyingqiye can only take place if the getihu firms are of sufficient quality. For instance, only if the—on average smaller—getihu firms are of sufficient quality, they will be able to challenge and stimulate the—on average larger—siyingqiye firms (Fritsch and Mueller 2004). Therefore, we interpret the strength of the interaction between getihu and siyingqiye firms, in both directions, as a reflection of the average quality of the getihu firms. We argue that a competitive getihu sector strongly contributes to the entrepreneurial ecosystem’s vibrancy and resilience, thereby facilitating the emergence of an “entrepreneurial” economy in China.

Hypotheses 1a and 1b are admittedly somewhat exploratory as the pool of getihu firms is expected to be heterogeneous with both lower- and higher-quality entrepreneurs choosing this type of private firm, where a proportion may also be necessity-based entrepreneurs (Sun et al., 2023). Nevertheless, at the aggregate level of regions, we do expect at least some positive interaction, hence H1a and H1b. However, in the remainder of our hypotheses derivation, we will assume that siyingqiye firms behave more according to the “entrepreneurial” economy, and getihu firms more according to the “managed” economy. This is because even the higher-quality getihu firms are legally restricted to a household ownership structure and a firm size upper limit. Siyingqiye firms do not face these restrictions, and hence it may be expected that this form of private enterprise is a better vehicle to reap the fruits of the opportunities that the “entrepreneurial” economy offers. The next hypotheses depart from these general assumptions. Of course, the goal of the paper is to empirically test whether these assumptions underlying the hypotheses below are actually valid in practice.

Remuneration of Labor

The remuneration of labor in a region, as proxied by the level of the average regional wage rate, may have positive and negative effects on the rate of private firms. We argue that the negative effects may dominate for getihu and the positive effects for siyingqiye, as explained below.

High wage rates imply that labor market participants may earn more income as an employee than as an entrepreneur, lowering the supply of entrepreneurs. Also, for homogeneous labor, high wages imply higher costs of employing personnel, which makes running a business with sustainable profit levels more difficult. Hence, the number of firms may be expected to be lower in high-wage regions (Ashcroft et al., 1991).

If we assume that getihu firms behave more in accordance with the “managed” economy (see above), these firms would tend to employ more homogeneous labor, where a higher remuneration of labor is associated with higher wage costs, implying a burden for the entrepreneur. Moreover, for individuals who consider starting an (opportunity-based) getihu firm, the higher remuneration in the wage sector may be an attractive alternative to running a getihu firm, in which expansion and earnings are restricted to an upper bound.

-

Hypothesis 2a: A region’s level of remuneration of labor is negatively related to the rate of getihu firms.

In contrast, particularly in high-tech industries, higher wages may actually be a sign of higher productivity levels of the employees, enabling firms to outperform their rivals (Okamuro, 2008). In more “entrepreneurial” economies, where producing at the technological frontier is more common and high productivity levels are key, higher wages may thus go together with higher employment (Audretsch and Thurik 2001). Such regional labor markets with highly productive employees are attractive environments to operate private firms. This may hold especially for siyingqiye firms which are not restricted in the number of (high-skilled) jobs they can provide at the technological frontier of production. Indeed, the availability of technical skills within the firm is an important determinant of small firm growth (Zhou et al., 2018).

Moreover, higher wages may imply a higher demand for products and services by consumers, and may therefore be associated with more firms in the region. Again, in an “entrepreneurial” economy, such increased demand typically involves demand for new, innovative products and services, which are best served by small niche markets (Audretsch and Thurik, 2004). Of course, getihu firms can also be perfectly capable of serving such markets, but again the siyingqiye form, allowing quick scale-up in case a new product or service is well received by consumers, seems to be an advantage.

Finally, the high productivity levels of employees and the increased consumer demand for specialized products and services implied by high regional wage rates may attract additional entrepreneurs migrating from outside the region to benefit from such regional advantages. Again, such migrating entrepreneurs who strategically choose their firm location are more likely to run siyingqiye firms, allowing greater firm expansion, rather than getihu firms which are smaller and household-based, and therefore more likely to locate in the place of birth or current residence (Cowling et al., 2019).

-

Hypothesis 2b: A region’s level of remuneration of labor is positively related to the rate of siyingqiye firms.

Stock of Human Capital

Opportunity-based entrepreneurial activities are associated with entrepreneurs’ backgrounds and prior experience (Djankov et al., 2006). According to Shane (2000), the factors that impact the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities are the possession of prior information and the cognitive ability to value existing opportunities. Kaish et al. (1991) state that those who are better at identifying a new opportunity have prior information complementary to the new information embedded in the opportunity, because specialized information is more useful than general information for most activities (Becker & Murphy, 1992). Therefore, we argue that people with a higher level of specialized education (or more generally, people with high human capital) are more likely to exploit such opportunities.

As human capital is the main determinant of entrepreneurs’ earnings (Van Praag 2005), regions with a higher proportion of college graduates (which indicates higher human capital stock levels) may generate higher rates of entrepreneurs and firms (Acs & Armington, 2004; Armington & Acs, 2002). However, as entrepreneurs with high human capital levels are typically able to obtain such high earnings by running large firms with many employees (Lucas, 1978), average firm size in regions with high stocks of human capital may be higher. Indeed, Van Praag and Van Stel (2013) show that in economies with higher educated labor forces, the number of employees per firm (i.e., average firm size) tends to be higher. Consistent with this evidence, Millán et al. (2014) show that entrepreneurial performance of the average entrepreneur is stronger in countries with higher educated populations, suggesting that labor market participants with the highest entrepreneurial ability rates select into entrepreneurship, as predicted by Lucas (1978). In addition, as before, the availability of a highly educated regional labor force may attract “siyingqiye” entrepreneurs from outside the region.

Thus, it may be expected that in regions with higher rates of college graduates, the number of entrepreneurs running larger (typically siyingqiye) firms is relatively higher. Accordingly, the number of entrepreneurs running smaller (typically getihu) firms will be relatively lower in such regions.

-

Hypothesis 3a: A region’s stock of human capital is negatively related to the rate of getihu firms.

-

Hypothesis 3b: A region’s stock of human capital is positively related to the rate of siyingqiye firms.

Institutional Environment

China is often claimed to have an underdeveloped institutional framework (Chen et al., 2013). World Bank (2013) reports that China ranks 96th out of 189 countries worldwide regarding the general ease of doing business. On a positive note, the report also reports that China ranks among the top-15 economies regarding improvements made in the ease of doing business between 2005 and 2013 (World Bank, 2013). Regarding such improvements, many studies have argued that China’s more stable and efficient institutions have helped Chinese entrepreneurial firms take long-term views and grow faster (Batjargal et al., 2013; Hitt et al., 2004). In particular, China’s legal protection of property rights has had positive effects on entrepreneurial activities in China (Cull and Xu 2005; Lu & Tao, 2010; Zhou, 2011).

Notwithstanding these institutional improvements, considerable differences in the institutional environment still exist between Chinese regions (Zhou, 2014). These may impact regional differences in private firm rates. In particular, in an institutional environment that is more business-friendly, the relative number of firms is expected to be higher. This effect may hold in particular for siyingqiye firms as these are more burdensome to set up and may have to deal with business regulations on a more frequent basis during the firm life cycle, including labor market and property rights regulations. We hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 4: A relatively well-developed institutional environment is positively related to the rate of siyingqiye firms.

In contrast, as getihu firms are already relatively easy to start and run (from a “red tape” perspective), we do not expect regional rates of getihu firms to be influenced by differences in the regional institutional environment. Accordingly, we do not formulate a hypothesis for getihu.

Agglomeration Effects

Heavily populated areas are attractive locations for firms because of several advantages of agglomeration. First, in dense areas, the local demand for products and services is high (Reynolds et al., 1994). Second, the local supply of highly educated workers is high, reducing the search costs for qualified labor (Wheeler, 2001). Third, the closeness of people and firms provides an environment that is particularly conducive to knowledge spillovers (Audretsch & Feldman, 1996), including those between universities, private companies, and regional governments (De Castro Peixoto et al., 2022). Other advantages include closeness of research institutions, closeness of suppliers, clustering of innovative firms from the same but also from different industries (Zhu et al., 2019), and room for the creation of niche markets related to a high diversity of the population and associated variety in demand for products and services (Bosma et al., 2008). Despite negative agglomeration effects such as higher input prices and congestion, the literature is dominated by the empirical evidence for positive agglomeration effects on new firm formation (e.g., Armington & Acs, 2002; Reynolds et al., 1994).

Particularly firms with growth potential may benefit from agglomeration advantages including big sales markets, easy access to qualified labor, and good conditions for knowledge spillovers (Raspe & Van Oort, 2011). We therefore hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 5: A region’s population density is positively related to the rate of siyingqiye firms.

Again, for getihu firms, who are more restricted by their legal form, we expect the above advantages of agglomeration to be much less a consideration for starting a business. Accordingly, we do not formulate a hypothesis for getihu.

Economic Openness

Economic openness is considered as one of the most important characteristics of transitional countries. Many latecomer countries have shown that economic openness affects the economic output and eventually the rate of economic growth, either by export or FDI. In this regard, Hu et al. (2023) also point at the importance of the technical level of export manufacturing products and show that in China, this level has increased considerably between 1990 and 2021. In the present study, we use inward FDI as an indicator of economic openness. For emerging countries, FDI contributes to the local economy development through financial capital and technology transfer. In particular, activities of multinational enterprises (MNEs) in host countries may generate knowledge externalities (technology spillovers) benefiting domestic firms in the local economy (Caves, 1996; Ramesh, 2013).

However, the other voice states that there might be no effect or even negative effects (Aitken & Harrison, 1999; Haddad & Harrison, 1993). Aitken and Harrison (1999) explain such a negative effect as “market stealing” or the crowding-out effect.Footnote 10 Caves (1996) and Blomström et al. (2000) also argue that the likelihood that MNEs will crowd out local firms is larger in developing than in developed countries. This is due to a higher technology gap between domestic and foreign firms, because FDI often represents a “death sentence” for local firms that usually cannot compete with MNEs that possess technological and financial advantages. The case for no effect refers to subsidiaries acting as enclaves in a developing country with lack of effective linkages with the local economy (Aitken & Harrison, 1999; Feinberg & Majumdar, 2001).

Pertaining to this study, we propose that economic openness, reflected by FDI, has a positive impact on entrepreneurship, where complementary effects dominate due to the reduced technological gap between MNEs and local Chinese firms and network linkage effects in between (Markusen & Venables, 1999; Rodriguez-Clare, 1996). Yang et al. (2011) stress that by the time China moves to the late stage of market transition, Chinese local firms have benefited from foreign firms’ modern technologies through licensing, international joint ventures (IJVs), and alliances. Complementary effects and networking effects in this stage therefore appear stronger than the crowding out effect. This stimulates local entrepreneurship if the necessary stimulating conditions are created (De Backer and Sleuwaegen 2003). Again, due to their bigger growth potential and their stronger internal knowledge base (compared to getihu), we expect siyingqiye firms to be complementary to MNEs whereas we do not necessarily expect a link between getihu firms and MNEs. We hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 6: A region’s economic openness is positively related to the rate of siyingqiye firms.

Methods

Data Source and Sample

We use two major data sources in this study. The first is formed by the various China Statistical Yearbooks from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC) database, covering 31 Chinese regions over 13 years (from 1997 to 2009, in total 403 region-year observations). The NBSC statistics, largely accurate and internally consistent (Chow, 1993), include data about population, economy, and society at the national and regional levels over years, quarters, and months for thirty-one Chinese provinces in twenty-three categories (for national accounts, population, finance, industry, agriculture, trade, education, health, welfare, etc.) and have been used extensively in many China related studies (e.g., Buckley et al., 2007; Chang and Xu 2008; Tian, 2007). The second data source is the database containing the institutional index developed by the Nevin Economic Research Institute (NERI) (Fan et al., 2010) to reflect the regional institutional environment. This index has integrated the values from five dimensions of China’s institutional environment: government and market forces, development of non-state-owned organizations, development of commodity markets, development of factor markets (in which local knowledge and scientist are evaluated), and the development of market intermediaries and the legal environment. This index has been extensively used in finance and economics (Chen et al., 2010), and has recently been introduced to the management literature as well (Gao et al., 2010; Schotter & Beamish, 2011; Shi et al., 2012).

Dependent Variable: Entrepreneurship

We define Chinese entrepreneurial activities as economic activities conducted by two types of private firms: getihu and siyingqiye. According to NBSC (2009), private enterprises are those having been registered at the departments of industrial and commercial administration for which the business operations are situated at a county town (i.e., a town where the county government is located), or at urban areas with administrative hierarchy higher than a county town. The main difference between getihu and siyingqiye is the number of employees that they can hire. Getihu are private businesses with a maximum of seven employees while siyingqiye are private businesses with more than seven employees. Besides the difference in the maximum number of employees, there are also some other important differences between getihu and siyingqiye. In particular, getihu are restricted to only use individual or household assets for running their firm but they register with a shorter and easier start-up procedure. In contrast, siyingqiye are given much more relaxed conditions in terms of more allowed sources of registered capital (i.e., shareholders can be from outside of the entrepreneur’s family), but are compulsory required to hold a fixed amount of registration capital, causing higher start-up costs.

Following the organizational status perspective of entrepreneurship (Audretsch et al., 2015), we measure entrepreneurship as the rate of private firms (cf. Congregado, 2008). We drew the number of getihu and siyingqiye private firms separately from each provincial Statistical Yearbook (from 1997 to 2009). We merged collected data and then divided the number of firms by the corresponding provincial population size to reflect the firm rate (per thousand capita). The variable names (as shown in Table 1) are GTHR for getihu rate and SYQYR for siyingqiye rate.

As we measure the rate of private firms rather than the rate of new private firms, our measure belongs to the category of static indicators of entrepreneurship (rather than dynamic indicators). Static indicators of entrepreneurship focus on both new and incumbent firms (or the business owners of these firms, e.g., self-employment) whereas dynamic indicators focus exclusively on new firms (Van Praag and van Stel, 2013, p. 337). It may be argued that in the Chinese context, where private enterprise is a relatively young phenomenon, incumbent private enterprises should not be taken for granted, and hence we include them in our entrepreneurship measure as well.

A limitation of our data base on regional rates of private firms is that the numbers are not available by sector of economic activity.

Independent Variables

We use the average (real) wage rate from towns and cities to measure remuneration of labor (e.g., Ashcroft et al., 1991; Okamuro, 2008). We abbreviate this variable as WAGE. Following previous studies (Acs & Armington, 2004; Millán et al., 2014), we measure a region’s stock of human capital by the share of population holding tertiary education. As tertiary education (rather than primary or secondary education) is most likely to be associated with productivity (Vandenbussche et al., 2006), we use the college graduation rate (per thousand capita) as a proxy, including graduates from both junior colleges (dazhuan) and senior colleges (daxue).Footnote 11 Dividing by population size, we express the number of college graduates per thousand capita. This variable is abbreviated in the regression as CGR (college graduates rate). To measure the quality of the institutional environment per region, we used the NERI index developed by the Nevin Economic Research Institute (NERI) (Fan et al., 2010). The index was drawn from the NERI index dataset and is abbreviated as IE. Agglomeration effects are measured by population density in this study (e.g., Armington & Acs, 2002; Reynolds et al., 1994). We divided the total population by the territory size of the corresponding region (abbreviated as PD). Economic openness is majorly echoed by the permission of foreign direct investment. We divide the total amount of foreign investment by the corresponding regional gross production (RGP) in the same year, and the variable is abbreviated as FDI. Finally, to estimate mutual interactions, we also included the (lagged) siyingqiye rate as a determinant in the getihu equation, and vice versa.

Control Variables

We incorporate two control variables in our empirical analysis. First, we control for regional industry structure. As firm size is larger in manufacturing compared to, e.g., services (and hence the relative number of firms lower), a regional economy with a higher share of manufacturing is expected to have a lower private firm rate. We calculated manufacturing industry and service industry shares (in terms of GDP) in the total regional economy and abbreviated them as MI and SI in the regression tables. Second, we use a proxy for total investments by state-owned units over regional GDP, labeled TIGDP. High investments from state-owned units may indicate strong competition from large, capital-intensive state-owned enterprises. In such regions, private firms may be crowded out and the rate of firms may be lower. The variable definitions are summarized in Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

Figure 2 shows the evolution over time of the rate of private firms (distinguishing between getihu and siyingqiye) while Fig. 3 provides a regional comparison for the most recent year 2009. Although the rate of siyingqiye is far lower than that of getihu, our data show that, compared to getihu firms, siyingqiye firms occur relatively more often in higher developed regions: the correlation between the regional rates of siyingqiye and of economic development (real GDP per capita) is significantly positive at 0.719 at 5% significance level, whereas this correlation is only 0.216 for the rate of getihu. Accordingly, the cross-regional comparison (see Fig. 3) presents a sharp gap between the most developed regions such as Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjing, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang which rank top on the siyingqiye rate, and some developing regions which in contrast rank higher on the getihu rate. These correlations of the private firm rates with the regional level of economic development (GDP per capita) raise the question of which economic antecedents underlying the regional level of economic development are able to explain the variations in private firm rates? This is the subject of our empirical analysis.

Table 3 in Appendix 1 presents descriptive statistics and the correlation matrix for the variables used in our empirical analysis. It shows that on average, the number of getihu has been about seven times higher than the number of siyingqiye. However, the table conceals large regional differences with regard to the relative number of getihu versus siyingqiye firms. Furthermore, the table confirms that also on other economic indicators, substantial regional differences exist within China (Liu et al., 2020).

Estimation Methodology

We aim at explaining the regional rates of getihu firms and siyingqiye firms over the period 1997–2009 from the explanatory variables described above. Moreover, we want to take account of the correlation between the two dependent variables, i.e., the getihu and siyingqiye rates. Therefore, we apply seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) estimation (e.g., Bosma et al., 2008, for a similar application) to provide separate sets of coefficients for both equations while acknowledging correlations between the error terms of both equations (Zellner, 1962, 1963).

We estimate three different set-ups of our two-equation model. In our first and main set-up, we include variables for all (31) regions and all (12) years (1998–2009) in our estimation sample and include regional fixed effects in our model.Footnote 12 Hereby we focus on explaining the variations over time of the regional rates of getihu and siyingqiye (as the structural cross-regional differences in these firm rates are captured by the regional fixed effects, i.e., the terms \({\beta }_{0i}\) in the model below). So, we test whether changes in our explanatory variables in a region lead to changes in firm rates in that particular region (dynamic approach). Our regression model looks as follows (indicators i and t represent region and year, respectively):

In our second set-up, we include logarithmic transformations of our independent and control variables as some model variables are highly skewed (see Appendix 1, Table 3). We thus control for the possibly disturbing influence of outlier observations, even if such observations may be legitimate.

In our third set-up, we include variables for all regions but include only the years 1998, 2003, and 2009. Here we do not include regional fixed effects but instead estimate a pooled (SUR) model.Footnote 13 Hereby we focus on explaining the variations across regions of the regional rates of getihu and siyingqiye, i.e., why do some regions have higher firm rates than other regions (static approach)? We assume that the cross-region samples for 1998, 2003, and 2009 are sufficiently independent to warrant pooling them in one regression (see Wennekers et al., 2007, for a similar set-up). Nevertheless, we do include year dummies to account for differences between these 3 years.

Results for our second and third set-up are included in Appendix 3 and are treated as robustness checks.

Results

The estimation results of our main SUR model set-up as described above (regional fixed effects model) are presented in Table 2.Footnote 14 Regarding the interaction between getihu and siyingqiye, we observe positive effects which are significant at the 1% level, in all three tables (models (1) and (2) in Table 2 and Tables 6 and 7 in Appendix 3). Moreover, the coefficients are in the same order of magnitude across the three specifications, rendering the results to be quite robust. We conclude that the interaction effects between the rates of getihu and siyingqiye are positive in both directions, supporting hypotheses 1a and 1b.

It is now interesting to consider which cross-effect dominates, in terms of strength. Clearly, as the size of the coefficient for the effect of siyingqiye on getihu (model (1)) is much higher, in absolute terms this effect dominates over the strength of the vice versa effect (getihu on siyingqiye). However, this is directly related to the much higher getihu rate (21.1 on average, see Table 2) compared to the siyingqiye rate (3.1 on average). It is more interesting to consider the relative impact of both cross-effects. To this end, we introduce a simulation analysis (see Appendix 2), where, in one exercise, we provide an exogenous impulse of 10% to the number of getihu and consider how the number of siyingqiye develops over time, based on our actually estimated parameter estimates of their mutual interactions (holding the other independent variables constant).Footnote 15 In a second exercise, we focus on the reverse impact (i.e., the impact on the number of getihu of a shock of 10% to the number of siyingqiye). We find that the elasticity of getihu on siyingqiye is 0.51 (i.e., a 10% increase in the number of getihu leads to a 5.1% increase in the number of siyingqiye) whereas the elasticity of siyingqiye on getihu is only 0.29.

Hence, the effect of the getihu rate on the siyingqiye rate is relatively stronger than the vice versa effect. Therefore, ceteris paribus the effect of other independent variables, our empirical analysis predicts that the gap between the number of siyingqiye and getihu will become smaller in the near feature. We refer to Appendix 2 for more details about this simulation exercise.

Regarding a region’s level of remuneration of labor, we find a significantly positive impact of the regional average wage rate on the rate of siyingqiye, in all three tables. As explained in our “Theory” section, higher wages may reflect higher productivity levels of employees, and also a high consumer demand for (new) products and services. As such regional economies provide an attractive environment to operate private firms, in particular firms which are not restricted in size (i.e., siyingqiye firms), the relative number of siyingqiye firms is higher. This result is in line with hypothesis 2b and also in line with the theory of the “entrepreneurial economy.” Regarding the impact of wages on the rate of getihu, results are mixed. Using the fixed effects model (Table 2), we find a positive impact, but in our two robustness checks (Tables 6 and 7), we find no significant effects. Hence, these results are not robust. Hypothesis 2a is not supported. In sum, the impact of average wages on the siyingqiye rate is in line with the “entrepreneurial economy” whereas the impact of wages on the getihu rate is not.

Regarding the impact of the regional stock of human capital, we see that the coefficient of the college graduates rate for siyingqiye is significantly positive in Tables 2, 6, and 7. Hence, in regions with relatively more higher-educated workers, the number of entrepreneurs running larger (siyingqiye) firms is relatively higher, as theorized in hypothesis 3b. Hypothesis 3a, stating that the number of smaller (getihu) firms is relatively lower in such regions, is only partly confirmed as the coefficient is significantly negative in Tables 2 and 6, but not significant in Table 7 (model 1).

Regarding the institutional environment, we find that regions with more business-friendly institutions have higher siyingqiye rates, both in Tables 2 and 7. However, the coefficient is not significant in Table 6. Hypothesis 4 is partly supported. For getihu, we find the opposite pattern: the coefficient is not significant in Tables 2 and 7 but significantly positive in Table 6.

On agglomeration effects, we find a positive relationship between a region’s population density and its rate of siyingqiye firms. In all three tables, the positive coefficient is significant at 1% level, lending strong support to hypothesis 5. For getihu, we find mixed results: a negative and significant relationship in Tables 2 and 7, and a non-significant coefficient in Table 6.

Regarding the impact of a region’s economic openness, as proxied by the rate of inward FDI, we find a negative relationship between inward FDI and the rate of siyingqiye in all three tables, although the coefficient is not significant in Table 6. Since our hypothesis 6 expected a positive sign, it is not supported. The relationship between inward FDI and getihu firms is not significant in all three tables, suggesting that getihu firms and MNEs operate on different markets.

Finally, results of our control variables are in line with our expectations: firstly, in regions with a higher share of manufacturing, the rate of siyingqiye is lower, probably reflecting a higher average firm size (as manufacturing firms require a considerable scale of operation to compensate for higher fixed costs); secondly, siyingqiye firms seem to find it hard to compete with SOEs (witness the negative sign of TIGDP in all three tables).

Discussion

In the present paper, we investigated to what extent antecedents of regional rates of getihu (private firms with a maximum of seven employees) and siyingqiye (private firms with more than seven employees) are in line with a modern, innovation-driven, “entrepreneurial” type of economy where knowledge-based entrepreneurship is key (Audretsch and Thurik 2004), or, alternatively, with an efficiency-driven economy still dominated by exploitation of mass production. This research question is important because if the regional antecedents of private firm rates are in line with an innovation-driven economy, it implies that on aggregate, private firms in China are of sufficient quality to compete in the modern global, knowledge-based economy. Alternatively, if the regional antecedents of private firm rates correspond with an efficiency-driven economy, this would imply that Chinese private firms are not fully equipped yet to compete in the modern global, knowledge-based economy. In other words, our research enables us to deduce the “quality” or competitiveness of two types of private firms in Chinese regions, and the likelihood that Chinese entrepreneurship can play a leading role in achieving future economic growth.

Extant literature has focused on the steep increase in the number of private firms in the last decades and the role of institutional transitions in this development (Yang & Li, 2008; Zhou, 2011, 2014). However, while academic attempts to explain the increase in the numbers of private firms are both necessary and laudable, such studies do not tell us whether on aggregate, private firms in China have sufficient levels of competitiveness to compete in the modern global, knowledge-based economy. Moreover, with the exception of one study (as far as we are aware)—Zhou (2011)—, extant literature does not distinguish between getihu and siyingqiye type of firms.Footnote 16 The aim of the present study is to shed light on the quality of the regional populations of these two types of private firms prevailing in China’s economy.

We developed six hypotheses related to the regional antecedents of the number of getihu and siyingqiye firms, and also the interaction between the two types of firms, which in part capture knowledge spillovers. We found that determinants of the regional rates of siyingqiye and getihu are substantially different. Among others, a region’s prevalence of college graduates is positively related to the rate of siyingqiye—similar to the findings of Acs and Armington (2004) for new firm formation in the United States—but not so to the rate of getihu. Our results also suggest that agglomeration advantages accrue to siyingqiye—again confirming results by Acs and Armington (2004) for the United States—rather than getihu firms. Thus, similar to new firm formation in the United States, siyingqiye firms are relatively more often present in regions where economic antecedents are conducive to knowledge production and knowledge spillovers. As knowledge is the main source of competitive advantage in innovation-driven economies, we may therefore deduce that regional incentive structures for siyingqiye seem to be in line with a modern competitive economy, where knowledge-based entrepreneurship is key.

Although siyingqiye firms thus seem to be conducive to China’s innovation-driven economic development, our results also show that the presence of large companies, either in the form of inward FDI or in the form of SOEs, still crowds out domestic siyingqiye firms. This suggests that, although China is transitioning towards an innovation-driven economy, and away from an efficiency-driven economy, economies of scale still play an important role in China’s contemporary economy. Especially the negative relationship between inward FDI and the regional rate of siyingqiye was a bit surprising to us and contradicted our hypothesis 6. We had expected a positive effect as inward FDI is assumed to be accompanied by technology spillovers which benefits domestic firms (Caves, 1996; Ha et al. 2021). However, Kowalski (2021) reports that the (extensive) literature on the role of inward FDI in China is actually inconclusive. Possibly, absorptive capacity of siyingqiye firms is not quite sufficient yet to actually benefit from technology spillovers from foreign multinationals. An alternative explanation, possibly explaining the negative relationships of siyingqiye rates with both inward FDI and SOEs, is that “Although public support for private enterprises exists, preferential policies have traditionally leaned towards state-owned and foreign-owned enterprises” (He et al., 2019, p. 564). In other words, industrial policy may play a role here as well.

Regarding getihu, we notice that antecedents of regional getihu rates are less in line with the “entrepreneurial economy.” For instance, we do not find evidence for a positive association between the education level of the regional population and the number of getihu firms. This may reflect that part of getihu firms are started out of a necessity-motivation, especially in rural China (Sun et al., 2023). When labor market participants have no other options for work, they may start their own firm, and the getihu form is then the easiest (and cheapest) organizational form to choose. However, notwithstanding the presence of necessity-motivated entrepreneurs in the getihu sector, nowadays entrepreneurial activity among getihu is increasingly opportunity-based.Footnote 17 In this respect, the getihu form may offer advantages also to ambitious entrepreneurs as the small scale and scope enables them to be flexible and use a lean business model in a low-profile environment to experiment with new ideas (Allen, 2022).Footnote 18

Our simulation exercise also seems to support this conjecture of an increasing quality of the getihu sector: we find that there is relatively strong interaction between regional rates of getihu and siyingqiye. We interpret the relatively strong interaction between the two types of firms as a sign that the getihu sector in China is of considerable quality, and that knowledge spillovers between getihu and siyingqiye take place abundantly. Regarding these interactions, we find that the impact of getihu on siyingqiye (estimated elasticity 0.51) is even stronger than vice versa (0.29), predicting that, ceteris paribus, the gap between the number of getihu and siyingqiye will decrease in the near future. As our study found that siyingqiye antecedents are more in line with the “entrepreneurial” economy, this predicted increase in the share of siyingqiye firms (relative to getihu) suggests that China is slowly but surely transitioning towards an “entrepreneurial” economy.

On balance, our results suggest that siyingqiye and getihu each play their own role in the modern Chinese economy. Siyingqiye firms have the possibility to grow and are therefore attractive to ambitious, opportunity-oriented entrepreneurs (Rypestøl, 2017). Our analysis suggests that siyingqiye entrepreneurship in China is indeed to a large extent opportunity-driven as its rates are found to be highest in regions where economic antecedents are conducive to running profitable, competitive firms in the modern knowledge-based economy. Nevertheless, siyingqiye rates are lower in regions with a high large-firm presence, marking China’s transitional stage between the efficiency-driven and innovation-driven economy, where economies of scale still play an important role.

In contrast, antecedents of getihu firms are less clearly linked to reaping the fruits of the “entrepreneurial” economy, possibly indicating that the getihu sector consists of a mixture between necessity-driven and opportunity-driven entrepreneurs. However, our analysis also suggests that the share of high-quality, opportunity-driven entrepreneurs in the getihu sector may be increasing, as getihu firms were found to play an important role by enabling the number of siyingqiye firms to increase. This last finding is in line with Rypestøl (2017) who explains that “Entrepreneurs play an important role in the evolutionary process of regional industries. As founders of new firms, entrepreneurs increase the supply side of the industrial economy, and by doing so, they challenge the incumbent firms to respond.” (p. 1). However, as explained in our “Derivation of Hypotheses” section, incumbent firms will only feel the need to respond if the threat of new competition is real, i.e., if the new entrants are of sufficient quality (Fritsch and Mueller, 2004). Our finding that the number of siyingqiye firms strongly responds to an increase in the number of getihu firms suggests that, on aggregate, the new getihu firms are indeed competitive, thereby contributing to an evolutionary process of regional industrial development and stimulating the overall level of regional economic performance as described by Rypestøl (2017).

Conclusion

Arguably the most important change in the transition of China from a centrally planned economy to a market-based economy was the admission and acknowledgement of private enterprises in the 1980s and 1990s in the form of getihu and siyingqiye firms. In this study, we explored the evolution and the economic antecedents of regional rates of siyingqiye and getihu over a decade (from 1997 to 2009), as well as the interactions between the regional rates of these two types of organizational forms. These interactions include knowledge spillovers flowing between getihu and siyingqiye firms. Our analysis enables us to reflect on the extent to which entrepreneurship development in China has been up to speed with transitioning to the innovation-driven stage of economic development in which the “entrepreneurial” type of economy prevails (Audretsch and Thurik, 2000, 2001).

An abundance of literature has studied various aspects of China’s transition to a market economy. However, only a minority of this literature has studied the regional antecedents of private firm rates, while the small number of existing studies (e.g., Yang & Li, 2008; Zhou, 2011, 2014) focuses on institutional determinants only and do not distinguish between different types of private firms. The present study addresses this research gap by investigating the regional antecedents of two types of private firms while considering not only institutional antecedents but also broader economic and social antecedents of regional entrepreneurship rates. Moreover, we interpret our findings using the theoretical lens of the “managed” versus the “entrepreneurial” economy dichotomy as introduced by Audretsch and Thurik (2000, 2001, 2004). Thus, the present study not only documents the variations in rates of siyingqiye and getihu—both across regions and over time—, but also explains them. We find that particularly the antecedents of regional siyingqiye rates are in line with the “entrepreneurial” economy in the sense that regional economies that are more conducive to knowledge production and knowledge spillovers have higher rates of siyingqiye firms. Overall, our analysis suggests that both types of entrepreneurship play important but distinct roles in stimulating China’s economic development.

Theoretical Implications

In recent decades, entrepreneurship research has evolved from viewing entrepreneurship as a homogeneous phenomenon where entrepreneurial agents start and manage their own businesses for their own account and risk, to recognizing the vast heterogeneity in the population of entrepreneurs (Wennekers & Van Stel, 2017). In particular, entrepreneurial firms differ in their “quality,” i.e., their productivity levels and their contributions to macro-economic growth. For instance, it is intuitive that a shoe cleaner offering his services on the street contributes less to macro-economic development than an owner-manager of a high-tech business, even though both may be considered entrepreneurs in the sense of managing their own businesses for their own account and risk. Therefore, it is important to create meaningful typologies of entrepreneurs where the different roles in economy and society of different types of entrepreneurs are underlined. Wennekers and Van Stel (2017) report a high number of dimensions or dichotomies along which such typologies can be made including ambitious vs. non-ambitious entrepreneurship, innovative vs. replicative entrepreneurship, social vs. profit-oriented entrepreneurship, opportunity vs. necessity entrepreneurship, solo vs. employer entrepreneurship, and many other possible dimensions. Each type of entrepreneurship plays its own role in economy and society, and we need to know more about the different roles played by different types of entrepreneurs. In this regard, another useful classification is made by Rypestøl (2017) who proposes a classification of entrepreneurial firms along the dimensions of innovation novelty and entrepreneurial growth intention, enabling better predictions of future regional industrial development.

In the Chinese context, where private firms and hence also the study of private firms is a relatively new phenomenon, it is not so usual yet to acknowledge the heterogeneity of entrepreneurship. However, the distinction made in the present study between getihu and siyingqiye types of firms may be considered a first step in studying the heterogeneity of entrepreneurship in China. The different regional antecedents found for getihu and siyingqiye in the present study, and the implied different roles in the economy played by the two types illustrate the importance of acknowledging entrepreneurship heterogeneity, also in the Chinese context. Future research should therefore also take account of the various differences between different types of entrepreneurship in China.

Managerial Implications