Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study is to assess the effectiveness of a brief online mindfulness intervention in reducing depression, rumination, and trait anxiety among university students.

Method

The sample consisted of 486 participants including 205 (42%) in the experimental group and 281 (58%) in the control group. For a period of 28 days, participants in the experimental group engaged in daily mindfulness meditation during their free time. Additionally, they practised mindfulness meditation once a week during regular class hours. The control group was involved in regular class activities without practising mindfulness. The outcomes were assessed at pre- and post-intervention using well-validated measures of mindfulness, depression, rumination, and trait anxiety. The data were analysed using mixed-model ANCOVA while controlling for baseline mindfulness levels as co-variates.

Results

Our results demonstrated the effectiveness of a brief online mindfulness intervention in reducing depression, rumination, and trait anxiety of university students. Moreover, higher baseline mindfulness levels predicted better effectiveness of the brief online mindfulness intervention at an individual level and were inversely linked to depression, trait anxiety, and rumination.

Conclusions

This study conclusively demonstrated that a brief online mindfulness intervention significantly reduces depression, rumination, and trait anxiety among university students, with reductions observed in specific measures of these conditions, highlighting the role of initial mindfulness levels in moderating outcomes. These findings underscore the effectiveness of brief online mindfulness programs in mitigating mental health issues in a university setting and the importance of baseline psychological states in intervention outcomes.

Preregistration

This study is not preregistered

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mindfulness is a state of awareness that emerges through active, open attention to the present. It is the ability to be fully present, aware of where we are and what we are doing, and not overly reactive, judgemental, or overwhelmed by what is going on around us (Kabat-Zinn, 2013; Shapiro & Carlson, 2009). Mindfulness is often described as “being in the moment”, and it is characterised by curiosity, openness, and a lack of judgement (Barcaccia et al., 2019; Medvedev et al., 2021); it has been found to be significantly and positively associated with measures of adjustment and negatively with measures of maladjustment (Barcaccia et al., 2020, 2022; Pleman et al., 2019; Schneider et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2020).

Mindfulness can be achieved through various practices such as meditation, yoga, and tai chi and is often referred to as “living in the present moment”. With mindfulness, individuals can learn to approach life with curiosity, openness, and a clearer mind, making it a valuable tool for promoting mental and physical wellness (Querstret et al., 2020). Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been widely researched and documented to have numerous benefits for mental and physical well-being (Krägeloh et al., 2019): mindfulness practices, such as meditation and yoga, have been shown to improve psychological well-being, reduce stress, improve mood, and heighten cognitive flexibility (Dalpati et al., 2022; Howarth et al., 2019; Kramer et al., 2023).

The studies evaluating the effectiveness of MBIs for university students using randomised controlled trials (RCTs) proved to be beneficial in decreasing stress (Galante et al., 2018, 2021), anxiety, and depression (Dawson et al., 2020; Vorontsova-Wenger et al., 2022). The study of Vorontsova-Wenger et al. (2022) evaluated the effectiveness of a short mindfulness intervention on anxiety, stress, and depression symptoms among 50 university students with high levels of depression, anxiety, or stress randomly allocated to a mindfulness practice group or an active control group. Students who underwent the mindfulness practice showed decreased levels of anxiety, stress, and depression compared to the control group. Dawson et al. (2020) conducted a meta-analysis on 51 RCTs assessing the effects of MBIs on university students’ mental and physical health: results showed that when compared with passive control groups, students in the experimental groups (MBIs) showed improvements in distress, anxiety, depression, rumination, and mindfulness, whereas when compared with active control groups, the experimental groups’ mindfulness, depression, and trait anxiety did not decrease, whereas distress and state anxiety significantly decreased.

With the advancement of technology, online mindfulness interventions have become increasingly popular as a convenient and accessible option for individuals seeking to improve their mental health (Sommers-Spijkerman et al., 2021). Online interventions have also been proven to be effective for a range of psychological problems, such as depression, stress, negative emotions, burnout, and sleep problems, leading to an overall increase in the well-being of adults (Xu et al., 2022).

Beneficial effects have been found on depression, anxiety, stress, and rumination with brief online MBIs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hosseinzadeh Asl and İl (2022), with a four-session online MBI, found significant improvements on depression, anxiety, stress, rumination, and mindfulness; Mirabito and Verhaeghen (2022), with an online 4-week mindfulness intervention, found significant benefits in mindfulness, rumination, worry, mood, stress, anxiety, and psychological well-being. Similarly, Simonsson et al. (2021), with an 8-week online MBI, found greater reductions in anxiety, but not in depression symptoms, for participants in the mindfulness condition compared to controls. González-García et al. (2021) showed that a brief online mindfulness and compassion-based intervention was effective in reducing stress and anxiety and in increasing self-compassion. Previous studies also showed how mindfulness can increase resilience and reduce the urge to cope with psychological discomfort in detrimental ways (Galante et al., 2018, 2021; Giacomantonio et al., 2022).

As universities grappled with the mental health fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, the necessity for interventions that could be delivered remotely and integrated into students’ changed lifestyles became clear. In anticipation of long-term shifts towards digitalised living and learning, our study was conceived to explore the potential of a brief, online mindfulness intervention to support university students’ mental well-being. Prior to the commencement of the trial, it was posited that such an intervention, if found effective, would have substantial implications for post-pandemic mental health strategies, offering a scalable and accessible solution well-suited to the evolving educational and social dynamics. This objective is aligned with the importance of integrating mindfulness in the public health system comprehensively outlined by Oman (2023) and represent a novel aspect not covered by this work. The intention was to contribute to the limited yet growing evidence on the efficacy of digital MBIs and to propose a proactive approach to integrating mental health support in post-pandemic university settings. This rationale set the stage for a study that, through its innovative design and contemporary relevance, aimed to inform future public health policies and educational practices in a world adapting to the lasting changes brought about by the pandemic. Based on previous literature, we predicted that our brief online MBI would be associated in the experimental group (with the mindfulness intervention), but not in the control group (without the mindfulness intervention) with a decrease of students’ (1) depressive symptoms, (2) anxiety, and (3) rumination. Moreover, we predicted that the initial trait mindfulness would be related to the decrease of students’ (1) depressive symptoms, (2) anxiety, and (3) rumination.

Method

Participants

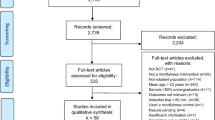

Participants were Educational Science students attending General Psychology (GP) class. The assignment to either the control or the experimental program was done using a cluster randomisation procedure. The sample consisted of 486 students (97% female), 205 (42%) in the experimental group (class 1) who participated in the online MBI and 281 (58%) to the control group (class 2). Participants’ mean age was 22.88 (range 19–60; SD = 6.39).

Procedure

The lectures of GP occurred in the two classes twice a week for 12 consecutive weeks in analogous virtual classrooms and shared the same course plan. In both the experimental and the control groups, students were requested at the beginning of class to switch off their mobile devices.

Only the experimental group (class 1) took part in the mindfulness intervention, which was delivered by the first author of this paper. The mindfulness instructor, a licensed clinical psychologist with formal MBSR training and a 10-year experience in teaching mindfulness meditation, was not involved in the teaching of the GP course. A recent meta-analysis showed that in school-settings only, MBIs delivered by outside instructors (not involved in the teaching) with previous training and experience of mindfulness have beneficial effects (Mettler et al., 2023).

This study was part of a larger project about the effects of a MBI for university students (Fagioli et al., 2023). All participants, before taking part in the study, gave informed consent and completed a series of questionnaires online twice: 1 week before the start of the MBI and 1 week after its completion.

Intervention

The intervention was based on the pillars of Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 2013). Participants in the experimental group engaged in guided mindfulness meditation during class once a week and also practised a daily breathing exercise over a period of 28 days. The in-class intervention consisted in a guided sitting meditation preceded by a brief introduction. Participants were asked to sit on a chair and instructions were provided on the physical posture (Kabat Zinn, 2013): (1) be seated on a chair, upright, with one’s eyes closed (or open, with a low gaze, if keeping them open was uncomfortable); (2) bring full attention to the present moment, notice what thoughts, emotions, urges, and feelings arise, allow every one of them to come and go; (3) go back to the physical sensations related to the breathing as an anchor for attention. Students were asked to put themselves in contact with their inner experiences with curiosity, openness, and acceptance.

The mindfulness trainer, for 4 consecutive weeks, led a 10-min breathing meditation at the beginning of each class. Students were invited to share their experiences and received feedback from the instructor, who, on the basis of the students’ sharing, took the opportunity to illustrate the basics of mindfulness (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). The whole intervention, including meditation, sharing, and mini-lecture, lasted about 30 min.

For the daily practice, participants were provided with an audio file of the breathing meditation and were asked to complete each day a brief survey to evaluate their compliance to the mindfulness practice. The whole intervention (guided meditation in-class and daily practice at home) lasted 4 weeks.

Measures

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The BDI (Beck, 1961) is a 21-item self-report inventory used to measure symptoms of depression. Participants are asked to indicate which statement best describes their feelings over the past 7 days. (Sample item: “I feel the future is hopeless and that things cannot improve”.) All responses are based on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. The total score is obtained by summing over the items, so that the higher the score, the higher the severity of depressive symptoms. Beck et al. (1988) reported a Cronbach alpha value of 0.86 for psychiatric patients and 0.81 for non-psychiatric individuals. In this study, both Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω) for this measure were 0.89.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Y (STAI-Y, trait subscale)

The STAI-Y (Spielberger, 1983) is a self-report inventory that measures trait anxiety. It consists of 20 items assessing trait anxiety (sample item: “I worry too much over something that really doesn’t matter”). Responses are based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from not at all to extremely. The total score is obtained by summing over the items, so that the higher the score, the higher the severity of anxiety symptoms. Previous research has demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha above 0.90) (Spielberger & Vagg, 1984; Spielberger et al., 1971). In this study, the scale demonstrated comparable internal reliability with α and ω both ≥ 0.82.

Ruminative Response Scale (RRS)

The RRS (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) is a self-report measure assessing the tendency to respond to depressed moods (sample item: “Think about all your shortcomings, failings, faults, mistakes”). The RRS consists of 22 items, all rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). In the present study, we used the total score, obtained by summing all the responses so that higher scores correspond to higher rumination. The RSS is both a reliable and valid measure of rumination and several studies showed a Cronbach α above 0.90 (Luminet, 2004; Roelofs et al., 2006). Internal reliability α and ω were both 0.92 in this sample.

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)

The FFMQ (Baer et al., 2006) consists of 39 items, all rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). The five facets of mindfulness operationalise the overarching construct of mindfulness: (a) Observe: observing, noticing, thoughts, emotions and sensations (sample item: “I notice the smells and aromas of things”); (b) Describe: describing or being capable of labelling with words one’s inner experience (sample item: “I’m good at finding words to describe my feelings”); (c) Act-with-awareness: acting with awareness, i.e. attending to the present moment with awareness, as opposed to acting automatically (sample item: “I am easily distracted”; (d) Non-judge: having a non-judgemental attitude toward one’s inner experience (sample item: “I tell myself I shouldn’t be feeling the way I’m feeling”); (e) Non-react: allowing thoughts and emotions to come and go, without getting caught up in them or carried away by them (sample item: “In difficult situations, I can pause without immediately reacting”). The validity and reliability of FFMQ were largely supported, indicating adequate and good internal consistency with alpha coefficients ranging from 0.72 to 0.92 (Baer et al., 2008; Christopher et al., 2012). Reliability coefficients computed with the current sample showed good internal consistency of the FFMQ (α = 0.87; ω = 0.84).

Data Analyses

The collected data from the 486 university student participants were prepared for analysis by initially ensuring completeness and accuracy, followed by a screening for outliers and normality testing. Preliminary analyses included descriptive statistics to characterise the sample in terms of demographic variables and baseline measures of mindfulness, depression, rumination, and trait anxiety. We employed the interquartile range (IQR) method to detect outliers, defining an outlier as any data point that lies more than 1.5 times the IQR below the first quartile or above the third quartile. This criterion is widely accepted in statistical analyses for its robustness in identifying outliers without being overly sensitive to the nuances of the data distribution.

The effects of mindfulness training on depression scores were investigated using mixed model factorial ANCOVA with intervention and control groups as between subject and pre- and post-intervention times as within-subject factors while controlling for baseline mindfulness levels (Roemer et al., 2021). The choice of ANCOVA was motivated by its ability to control for baseline variability, its suitability for testing interaction effects in a mixed design, its efficiency in terms of statistical power, and its flexibility in handling the types of variables in our study. This methodological approach allowed us to provide a nuanced analysis of the intervention’s effectiveness, controlling for relevant covariates and thereby contributing to the robustness and reliability of our findings.

This analytic strategy incorporated a 2 × 2 matrix: comparing the experimental group against the control group and juxtaposing measurements taken before the intervention commenced with those gathered after its conclusion. In this schema, the “group” variable served as the between-subjects element, while “time” operated as the within-subjects element. A critical aspect of this analysis was the interaction between “time” and “group”. Detecting a statistically significant interaction here was pivotal, as it would signal varying trajectories in depression, rumination, and anxiety levels among participants before and after the mindfulness intervention, contingent upon their group allocation.

In our analysis, the homogeneity of regression slopes assumption was tested as part of the ANCOVA procedure. This assumption checks that the relationship between the covariate (pre-intervention mindfulness levels) and the dependent variables (depression, rumination, and trait anxiety scores) is the same across both the intervention and control groups. Specifically, we included interaction terms between the covariate (baseline mindfulness levels) and the independent variable (group assignment) in the initial model to test for the presence of any significant interaction effects. The absence of significant interactions between the covariate and group assignment would indicate that the slopes of the regression lines are homogeneous, thus validating the assumption.

We conducted power analysis for the current experimental design indicating that detecting a small effect size of 0.25 with 95% confidence under p = 0.05 requires a minimum sample size of 210 participants. Our sample size exceeds this estimation.

Results

The data were complete and distributed nearly normally (skewness and kurtosis values within ± 2), with equal variances across groups and time points as evidenced by non-significant Levene’s test and there were no significant outliers. Figure 1 illustrates marginal means of depression for intervention and control groups measured pre- and post-intervention while controlling for baseline levels of mindfulness. A stronger decrease in depression levels was observed in the intervention group after the intervention, compared to the control group while pre-intervention levels of depression were comparable between groups. This observation is statistically supported by ANCOVA indicating a significant moderate interaction effect between group and time (F(1, 483) = 17.55, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04). Mindfulness at baseline significantly predicted depression scores with a large effect size (F(1, 483) = 177.50, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.27). There was also a statistically significant modest effect of time (F(1, 483) = 12.28, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03). There was no significant interaction between mindfulness covariate and group for depression suggesting that the covariate’s effect is independent of the treatment effect (F(1,483) = 2.36, p = 0.88).

As shown in Fig. 2, rumination also decreased after intervention but only in the intervention group and this decrease was statistically significant as evidenced by ANCOVA and post hoc tests (F(1, 483) = 12.05, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.02). There was also a significant effect of pre-intervention mindfulness levels on rumination scores (F(1, 483) = 152.85, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.24). No significant interaction was observed for rumination outcome between mindfulness covariate and group suggesting that covariate is independent from the treatment effect (F(1,483) = 0.02, p = 0.90).

Similarly, there was a stronger reduction of trait anxiety in the intervention group compared to the control group at post-intervention that can be observed in Fig. 3, and statistically supported by significant group-time interaction (F(1, 483) = 12.43, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03). Baseline mindfulness levels also significantly predicted lower anxiety with a large effect size (F(1, 483) = 249.47, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.34). The interaction between mindfulness covariate and group was not significant for trait anxiety suggesting that the covariate is independent from treatment effect (F(1,483) = 0.47, p = 0.49).

Descriptive statistics including means and SD for all study variables at pre (T1) and post (T2) intervention are included in Table 1. Note that these descriptive values were not adjusted for baseline mindfulness levels, and hence different from values displayed on Figs. 1, 2, and 3. This adjustment is crucial because individuals’ initial mindfulness can significantly influence their response to the intervention, potentially affecting outcomes such as depression, rumination, and trait anxiety. Therefore, to accurately assess the intervention’s effectiveness, Figs. 1, 2, and 3 present data that have been adjusted for these baseline levels. This adjustment ensures a more precise evaluation of the intervention’s impact by accounting for individual differences in mindfulness at the start of the study. Consequently, while Table 1 offers a straightforward comparison of pre- and post-intervention scores, Figs. 1, 2, and 3 provide a deeper insight into the intervention’s effects, controlling for initial mindfulness variations among participants. Understanding this distinction is vital for interpreting the results accurately, as it highlights the intervention’s true effectiveness by considering the starting point of each participant’s mindfulness level.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a brief online mindfulness intervention on depression, rumination, and trait anxiety in university students while controlling for their baseline mindfulness levels. The results of the study demonstrated its effectiveness, as evidenced by the significant reduction in levels of depression, rumination, and trait anxiety in university students after the intervention compared to the control group. These findings have wide-ranging implications for public health, as they suggest that online mindfulness interventions may be an effective means of addressing common mental health challenges in this population. Moreover, the study highlights the role of baseline mindfulness levels in determining the effectiveness of mindfulness interventions (Roemer et al., 2021). The finding that initial trait mindfulness is inversely linked to depression, anxiety, and stress further supports the importance of considering baseline mindfulness levels when evaluating the impact of mindfulness interventions.

Overall, these findings contribute to the growing body of evidence on the benefits of MBIs for mental health and can inform the development of more effective and personalised approaches to mental health treatment. Additionally, the results of this study may also encourage more widespread adoption of online mindfulness interventions as a convenient and accessible means of improving mental health, particularly among university students. Our study’s findings reveal that a brief online mindfulness intervention effectively reduces depression, rumination, and trait anxiety among university students, which is consistent with previous research (Dawson et al., 2020; Galante et al., 2018, 2021; Vorontsova-Wenger et al., 2022). By utilising a randomised controlled trial, our study contributes to the existing literature and underscores the positive impact of such interventions for university students.

Our findings are also in line with studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic that reported positive effects of brief online MBIs on depression, anxiety, stress, and rumination (González-García et al., 2021; Hosseinzadeh Asl & İl, 2022; Mirabito & Verhaeghen, 2022; Simonsson et al., 2021). These studies support the idea that online mindfulness interventions can be an effective and easily accessible means of enhancing mental health, especially during challenging times when traditional face-to-face interventions may not be feasible.

Our findings offer valuable insights into how mindfulness interventions can be integrated into academic environments to enhance student outcomes and well-being. For instance, the notable decrease in rumination aligns with the potential for improved academic performance. Rumination, often linked to depression, can significantly impact cognitive processes such as attention, memory, and problem-solving (Kievit & Peng, 2020). Therefore, addressing rumination can contribute to more effective learning and higher academic achievements. Educational institutions can incorporate mindfulness training into their academic curricula or offer it as an extracurricular activity to help students manage their ruminative thoughts and enhancing their capacity to focus on their studies.

It is essential to highlight how our findings could revolutionise the way mindfulness is integrated into the public health system, especially in the context of university settings grappling with the mental health challenges exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated a shift towards more digitalised living and learning, and our study shows that mindfulness interventions can be adapted to these changes effectively. The significance of our findings resonates with the comprehensive outline for integrating mindfulness in the public health system as discussed by Oman (2023). Our work builds upon and extends the ideas presented by Oman, offering fresh insights into the practical application and scalability of digital mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs).

By providing evidence of the efficacy of a brief, online mindfulness program, our study not only supports the notion that mental health interventions can be both effective and accessible but also underscores the importance of considering individual differences in trait mindfulness. This points towards a more tailored approach in mental health strategies, where interventions can be adapted based on initial mindfulness levels to enhance their effectiveness.

Additionally, the reported decrease in depression and trait anxiety suggests a pathway to improved mental health among students. As mental health directly influences students’ motivation, performance, and overall success in their academic journey, providing mindfulness intervention resources can be a proactive and low-cost approach to support students’ mental well-being. For instance, student support services can use our study’s model to design online mindfulness programs that are accessible to all students, aiding in alleviating the symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Limitations and Directions of Future Studies

Despite the promising findings of this study, there are several limitations that should be considered. First, our study employed cluster randomisation rather than individual randomisation. Hence, the possibility of some confounding variables such as cluster-specific dynamics cannot be excluded. In this type of study, only a randomised controlled trial (RCT) could demonstrate that the observed effects are due to the employed intervention, and not to other variables. Second, we only used self-report measures. Third, the study was conducted over a relatively short period of time, and without a follow-up assessment. Thus, the long-term effects of the mindfulness intervention remain unclear. Fourth, the study only assessed the impact of mindfulness on depression, rumination, and trait anxiety, and it would be valuable to assess the impact on other mental health outcomes in future studies. Fifth, the current study relied on a sample comprised solely of psychology students at one urban university. This limits the generalisability of the findings to other populations and contexts. Further research should investigate the intervention used here among more diverse groups outside of academia, such as in workplace or community settings. Applying this brief intervention among professionals at various stages of their careers could provide insight into its potential benefits for improving psychological functioning in high-stress environments.

The results of our study, along with its limits, suggest several directions for future research. Firstly, additional studies could be conducted to determine the generalisability of these findings to other populations, including different age groups and individuals with mental health conditions. Secondly, longer-term follow-up studies would be valuable in determining the durability of the effects of mindfulness on depression, rumination, and trait anxiety. Finally, future studies should aim to assess the impact of mindfulness on a wider range of mental health outcomes and to identify the specific mechanisms through which mindfulness may be impacting mental health. The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the impact of brief online mindfulness interventions on university students and suggest that these interventions may be an effective means of reducing depression, rumination, and trait anxiety. Despite its limitations, this study contributes to the development of more effective and personalised approaches to mental health treatment. In conclusion, the incorporation of mindfulness interventions in university settings, informed by our findings, could contribute to an educational environment that promotes not only academic success but also the mental health and overall well-being of students.

Data Availability

The data is not publicly available due to the ethical restrictions for collecting data from the vulnerable population.

References

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., Walsh, E., Duggan, D., & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313003

Barcaccia, B., Cervin, M., Pozza, A., Medvedev, O. N., Baiocco, R., & Pallini, S. (2020). Mindfulness, self-compassion and attachment: A network analysis of psychopathology symptoms in adolescents. Mindfulness, 11(11), 2531–2541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01466-8

Barcaccia, B., Hartstone, J. M., Pallini, S., Petrocchi, N., Saliani, A. M., & Medvedev, O. N. (2022). Mindfulness, social safeness and self-reassurance as protective factors and self- criticism and revenge as risk factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in youth. Mindfulness, 13(3), 674–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01824-0

Barcaccia, B., Baiocco, R., Pozza, A., Pallini, S., Saliani, Mancini, F., & Salvati, M. (2019). The more you judge the worse you feel. A judgemental attitude towards one’s inner experience predicts depression and anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 1, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.012

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Garbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5

Christopher, M. S., Neuser, N. J., Michael, P. G., & Baitmangalkar, A. (2012). Exploring the psychometric properties of the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. Mindfulness, 3(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0086-x

Dalpati N., Jena S., Jain S., Sarangi P. (2022). Yoga and meditation, an essential tool to alleviate stress and enhance immunity to emerging infections: A perspective on the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on students. Brain, Behavior & Immunity–Health, 20, 100420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2022.100420.

Dawson, A. F., Brown, W. W., Anderson, J., Datta, B., Donald, J. N., Hong, K., Allan, S., Mole, T. B., Jones, P. B., & Galante, J. (2020). Mindfulness-based interventions for university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 12(2), 384–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12188

Fagioli, S., Pallini, S., Mastandrea, S., & Barcaccia, B. (2023). Effectiveness of a brief online mindfulness intervention for university students. Mindfulness, 14(5), 1234–1245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02128-1

Galante, J., Dufour, G., Vainre, M., Wagner, A. P., Stochl, J., Benton, A., Lathia, N., Howarth, E., & Jones, P. B. (2018). A mindfulness-based intervention to increase resilience to stress in university students (the Mindful Student Study): A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Public Health, 3(2), e72–e81. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(17)30231-1

Galante, J., Stochl, J., Dufour, G., Vainre, M., Wagner, A. P., & Jones, P. B. (2021). Effectiveness of providing university students with a mindfulness-based intervention to increase resilience to stress: 1-year follow-up of a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 75(2), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214390

Giacomantonio, M., De Cristofaro, V., Panno, A., Pellegrini, V., Salvati, M., & Leone, L. (2022). The mindful way out of materialism: Mindfulness mediates the association between regulatory modes and materialism. Current Psychology, 41, 3124–3134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00850-w

González-García, M., Álvarez, J. C., Pérez, E. Z., Fernandez-Carriba, S., & López, J. G. (2021). Feasibility of a brief online mindfulness and compassion-based intervention to promote mental health among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mindfulness, 12(7), 1685–1695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01632-6

Hosseinzadeh Asl, N. R., & İl, S. (2022). The effectiveness of a brief mindfulness-based program for social work students in two separate modules: Traditional and online. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 19(1), 42–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2021.1964670

Howarth, A., Smith, J. G., Perkins-Porras, L., & Ussher, M. (2019). Effects of brief mindfulness-based interventions on health-related outcomes: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 10(10), 1957–1968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01163-1

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living, revised edition: how to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation. Hachette UK.

Kievit, R. A., & Peng, P. (2020). The development of academic achievement and cognitive abilities: A bidirectional perspective. Child Development Perspectives, 14(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12352

Krägeloh, C. U., Henning, M. A., Medvedev, O., Feng, X. J., Moir, F., Billington, R., & Siegert, R. J. (2019). Mindfulness-based intervention research characteristics approaches and developments. Routledge.

Kramer, Z., Pellegrini, V., Kramer, G., & Barcaccia, B. (2023). Effects of insight dialogue retreats on mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological well-being. Mindfulness, 14(3), 746–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-02045-9

Luminet, O. (2004). Measurement of depressive rumination and associated constructs. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment (pp. 187–215). Wiley.

Medvedev, O. N., Cervin, M., Barcaccia, B., Siegert, R. J., Roemer, A., & Krägeloh, C. U. (2021). Network analysis of mindfulness facets, affect, compassion and distress. Mindfulness, 12(4), 911–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01555-8

Mettler, J., Khoury, B., Zito, S., Sadowski, I., & Heath, N. L. (2023). Mindfulness-based programs and school adjustment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 97, 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2022.10.007

Mirabito, G., & Verhaeghen, P. (2022). Remote delivery of a koru mindfulness intervention for college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American College Health, 70, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2060708

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and distress following a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61

Oman, D. (2023). Mindfulness for global public health: Critical analysis and agenda. Mindfulness. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02089-5

OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (Mar 14 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

Pleman, B., Park, M., Han, X., Price, L. L., Bannuru, R. R., Harvey, W. F., Driban, J. B., & Wang, C. (2019). Mindfulness is associated with psychological health and moderates the impact of fibromyalgia. Clinical Rheumatology, 38(6), 1737–1745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04436-1

Querstret, D., Morison, L., Dickinson, S., Cropley, M., & John, M. (2020). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for psychological health and well-being in nonclinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Stress Management, 27(4), 394–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000165

Roelofs, J., Muris, P., Huibers, M., Peeters, F., & Arntz, A. (2006). On the measurement of rumination: A psychometric evaluation of the ruminative response scale and the rumination on sadness scale in undergraduates. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 37(4), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2006.03.002

Roemer, A., Sutton, A., Grimm, C., & Medvedev, O. N. (2021). Effectiveness of a low-dose mindfulness-based intervention for alleviating distress in young unemployed adults. Stress and Health, 37(2), 320–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2997

Schneider, M. N., Zavos, H. M. S., McAdams, T. A., Kovas, Y., Sadeghi, S., & Gregory, A. M. (2019). Mindfulness and associations with symptoms of insomnia, anxiety and depression in early adulthood: A twin and sibling study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 118, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.002

Shapiro, S. L., & Carlson, L. E. (2009). What is mindfulness? In S. L. Shapiro & L. E. Carlson (Eds.), The art and science of mindfulness: Integrating mindfulness into psychology and the helping professions (pp. 3–14). American Psychological Association.

Simonsson, O., Bazin, O., Fisher, S. D., & Goldberg, S. B. (2021). Effects of an eight-week, online mindfulness program on anxiety and depression in university students during COVID-19: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Research, 305, 114222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114222

Sommers-Spijkerman, M., Austin, J., Bohlmeijer, E., & Pots, W. (2021). New evidence in the booming field of online mindfulness: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Mental Health, 8(7), e28168. https://doi.org/10.2196/28168

Spielberger, C. D., Gonzalez-Reigosa, F., Martinez-Urrutia, A., Natalicio, L. F., & Natalicio, D. S. (1971). The state-trait anxiety inventory. Revista Interamericana de Psicologia/Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 5(3 & 4).

Spielberger, C. D., & Vagg, P. R. (1984). Psychometric properties of the STAI: a reply to Ramanaiah, Franzen, and Schill. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(1), 95-97. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4801_16

Vorontsova-Wenger, O., Ghisletta, P., Ababkov, V., Bondolfi, G., & Barisnikov, K. (2022). Short mindfulness-based intervention for psychological and academic outcomes among university students. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 35(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2021.1931143

Wilson, J. M., Weiss, A., & Shook, N. J. (2020). Mindfulness, self-compassion, and savoring: Factors that explain the relation between perceived social support and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 152, 109568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109568

Xu, J., Jo, H., Noorbhai, L., Patel, A., & Li, A. (2022). Virtual mindfulness interventions to promote well-being in adults: A mixed-methods systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 300, 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.027

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all participants who kindly provided their data for this study.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Barbara Barcaccia: conceptualisation, methodology, writing–original draft preparation, reviewing and editing. Oleg N. Medvedev: conceptualisation, data analyses, reviewing and editing. Susanna Pallini: conceptualisation, writing–reviewing and editing. Stefano Mastandrea: resources and editing. Sabrina Fagioli: conceptualisation, resources, data curation, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by IRB from Roma Tre University Ref.UEC4/22.

Informed Consent

All participants provided their informed consent before participating in the study.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI tool ChatGPT Plus was used to check grammar and improve English language (OpenAI, 2023).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barcaccia, B., Medvedev, O.N., Pallini, S. et al. Examining Mental Health Benefits of a Brief Online Mindfulness Intervention: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 15, 835–843 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02331-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02331-8