Abstract

Objectives

The Applied Mindfulness Process Scale (AMPS) is a measure used to quantify the level at which individuals apply learned mindfulness skills during and after a mindfulness-based intervention (MBI). The AMPS was previously developed and validated among individuals with mindfulness experience and in good health. The utility of the AMPS among individuals receiving an MBI for a clinical disorder has not been examined.

Method

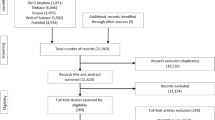

We tested the reliability, nomological validity, and incremental validity of the AMPS in a sample of women with substance use disorder (SUD) engaged in an MBI (n=100).

Results

AMPS and its subscales displayed adequate internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha range = 0.80–0.97) at each assessment, and test-retest reliability correlations were small to moderate in magnitude (Spearman’s ρ range = 0.22–0.74). AMPS scores averaged across assessments correlated with conceptually related measures in the expected directions at post-intervention (Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, (FFMQ,) r = 0.44, p < 0.01; Perceived Stress Scale, PSS, (PSS) r = −0.30, p < 0.01; Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale, (DERS,) r = −0.48, p < 0.01). AMPS explained variance in DERS beyond conventional mindfulness measures (MBI class attendance, mindfulness practice effort, FFMQ) at post-intervention (β = −0.32, p < 0.05).

Conclusions

The AMPS broadens the ability to capture behavioral aspects associated with therapeutic change that are distinct from conventional measures of practice quantity and mindfulness disposition. The measure yields predictive value for emotion dysregulation, a common target of MBIs. Factor analytic work is needed in clinical, novice meditator samples.

Preregistration

This study was not preregistered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) refer to programs used to train individuals in mind-body practices in order to cultivate a capacity for mindfulness in daily life (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Mindfulness is the ability to inhabit the present moment and to be aware, without judgement, of one’s moment to moment, and shifting cognitive and affective experiences (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Mindfulness practice, as a combination of meditation behaviors (e.g., sitting in an upright yet relaxed posture with eyes slightly closed) and psychological intentions (e.g., focus on the sensory experience of the breath without judging that experience), is commonly regarded to reduce psychological suffering via a shift in the individual’s relationship with pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral subjective experiences (Black, 2014).

The original MBI model (Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction; MBSR) involves intensive training in mindfulness practice via eight weekly classes, a full “retreat day,” and daily home assignments (Santorelli et al., 2017). The MBSR model has been adapted for a wide range of medical problems and psychiatric disorders (Goldberg et al., 2018). Several intervention packages have borrowed the model to adapt it to the needs of individuals with substance use disorder (SUD), such as to address sensory experiences particular to craving and relapse prevention (Amaro & Black, 2021; Black & Amaro, 2019; Priddy et al., 2018). A recent meta-analysis of 42 studies using between-group trial designs showed that MBIs yield a statistically significant reduction in substance use and craving among those with problematic substance use (Li et al., 2017). Thus, a close examination of the skills that participants obtain and enact during an MBI would likely be informative. Such knowledge could enhance understanding of the mechanisms through which MBIs influence substance use outcomes.

MBI programs commonly include recommended daily meditation practice (Carmody & Baer, 2008; Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Santorelli et al., 2017). Practice typically refers to time spent meditating as well as to the individual’s application of skills and concepts learned from meditation in daily life. MBI curricula include training in a variety of formal practices (e.g., setting aside time each day to practice mindful breathing or walking meditation) and informal practices (e.g., practicing being mindful of one’s meal while eating or noticing when one is distracted by one’s own thinking during a conversation) (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). It has been argued that daily practice and application of learned mindfulness skills promote self-regulation of attention and emotion and change in perspective away from identification with a static sense of self (Hölzel et al., 2011). Similarly, self-regulation and de-identification are proposed as mechanisms by which MBIs improve clinical symptoms of SUDs (Garland et al., 2014).

As with most types of skill development, consistent practice and application are requisite to gain the expected benefit. There is evidence that several skills relevant for individuals in SUD treatment may be cultivated and applied via consistent mindfulness practice, including the ability to exert cognitive control over automatic habits (i.e., to pause in the face of substance use triggers and respond wisely rather than automatically using a substance), the ability to manage stress, and the ability to derive pleasure from mundane experiences (i.e., “savoring”) (Priddy et al., 2018). The way and extent to which individuals apply specific behavioral practices may function to influence clinical outcomes among MBI participants. For example, mindfulness practice and application in daily life may enhance one’s general sense of wellness, reduce substance use, and enhance their ability to cope with cravings and distressful experiences while in treatment for SUD. Further, use of applied mindfulness practices in daily life may differ depending on the clinical population receiving an MBI (for example, certain practices may be beneficial for depression, while others may support substance use relapse prevention) (Chiesa et al., 2014; Chiesa & Malinowski, 2011). The psychometric study of the skills learned and applied during and after mindfulness practice and their association with transdiagnostic features of clinical samples (e.g., emotion regulation, stress, and craving) remains nascent, however.

A participant’s level of mindfulness during an MBI is commonly measured in two ways: mindfulness practice as a dimension of behavior (time in minutes meditating, number of days meditating, attendance at MBI class sessions, etc.) or as one’s subjective perception made that they are engaging in present-moment oriented attention without judgement (Goleman & Davidson, 2017). Several psychometric instruments based on self-report of mindfulness are available to test for change in the latter, that is, one’s subjective perception of their level of mindfulness as a disposition (Sauer et al., 2013). Among those most cited are the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS;) (Brown & Ryan, 2003) and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006), which have been statistically validated among several clinically and socio-demographically diverse samples (Black et al., 2012; González-Blanch et al., 2022; Watson-Singleton et al., 2018). While these scales are designed to capture the presence or absence of mindfulness disposition (e.g., the extent to which a person is attentive and non-judgmental towards their moment-to-moment experience), they are not designed to capture the behavioral processes of applying mindfulness as a learned skill in a practitioner’s day-to-day life and in response to routinely experienced life challenges and stressors. Applied behavioral measures are underdeveloped in the MBI field yet could be used capture the extent to which a person applies mindfulness skills in their daily life, rather than how a person perceives their dispositional tendency towards mindfulness upon self-reflection of the recent past.

Unique to extant measures, the Applied Mindfulness Process Scale (AMPS) was developed as a behavioral measure of mindfulness practice to capture the level at which individuals intentionally apply mindfulness skills in daily life and in response to stressors as skills are learned during mindfulness training (M. Li et al., 2016). The development of the AMPS was guided by empirical literature on mindfulness and coping and involved interviews with experienced mindfulness practitioners regarding their use of mindfulness practice in daily life (Baer, 2003; Benson et al., 1974; Garland et al., 2015; Teasdale et al., 1995). AMPS developers aimed to capture how often someone engages in mindfulness practices including decentering (the use of mindfulness to gain psychological distance from negative thoughts and feelings and to recognize thoughts are not veridical truths, e.g., “I used mindfulness practice to observe my thoughts in a detached manner”), positive emotion regulation (the use of mindfulness to refocus on positive emotional experience and positively reappraise life events, e.g., “I used mindfulness practice to be aware of and appreciate pleasant events”), and negative emotion regulation (the use of mindfulness to reduce emotional distress associated with stressors, e.g., “I used mindfulness to calm my emotions when I am upset”) (M. Li et al., 2016). In the original psychometric study of the AMPS, the measure showed strong internal consistency and test-retest reliability; there was evidence for nomological validity as the AMPS correlated positively with dispositional mindfulness and negatively with perceived stress and psychological distress. These results were among a sample of mostly White healthy adults who had experience in mindfulness practice. There remain gaps in knowledge regarding the psychometric properties of the AMPS in samples receiving an MBI for a clinical disorder, those who do not have previous experience with mindfulness practice, and among more racially and ethnically diverse populations.

Our objective was to test the utility of the AMPS in a diverse sample of women diagnosed with SUD. Using secondary data from participants who received an MBI as part of a clinical trial and were assessed six times across a 6-week intervention period, we assessed the reliability, nomological validity, and incremental validity of the AMPS as a behavioral measure of mindfulness skills applied in daily life. We hypothesized the AMPS would meet conventional standards for scale reliability in a clinical sample and AMPS scores would explain additional variance in conceptually related therapeutic mechanisms of MBIs (i.e., scores on the AMPS would be negatively associated with difficulties with emotion regulation, perceived stress, and craving) over and above the effects of established measures of mindfulness disposition and practice (i.e., FFMQ, MBI class attendance, time spent practicing mindfulness). Support for these hypotheses would suggest the utility of adding AMPS to the repertoire of measures yielding information about behavioral change that occurs during an MBI targeting SUD, whereas null effects would indicate that the AMPS may not meet psychometric standards and may not have clinical utility in terms of detecting change in a sample diagnosed with SUD.

Methods

Participants

Participants were originally recruited for a randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of the Moment-by-Moment in Women’s Recovery (MMWR) program, an MBI adapted for women with SUD and histories of trauma (Amaro & Black, 2017, 2021; Black & Amaro, 2019). Participants were women in residential SUD treatment and randomized to receive 12 class sessions over 6 weeks (two2 class sessions per week) of either the MMWR intervention or psychoeducation on the neurobiology of addiction (see Amaro & Black, 2021 and Black & Amaro, 2019 for previously published trial results). Women had to be residents at the treatment study site, enrolled in the trial, age 18–65 years, fluent in English, and agree to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were an inability to consent, cognitive impairment, untreated psychosis, severe psychiatric problems, current incarceration, past 30-day suicidality, >6 months pregnancy, enrollment in another study, and refusal to sign a confidentiality agreement.

Table 1 provides descriptive characteristics for the analytic sample at baseline. The mean age of the sample was 32.4, 60% of women were Hispanic or Latina, 18% were Black, and 47% had less than a high school education. Participants had either alcohol use disorder (AUD) (9%) or drug use disorder (DUD) (74%), or both AUD and DUD (14%). A sample majority (60%) had at least one mental health diagnosis in addition to their diagnosis of SUD. Table 2 provides sample distributions for the composite AMPS and AMPS subscales at each assessment.

Procedure

For the present study, we performed secondary analyses on data from the MMWR group (n=100) of the parent study. Participants completed the AMPS at intervention Sessions 3, 6, 9, and 12 (the AMPS was not administered to the control group as the measure was specific to learned mindfulness skills in MMWR). The trial was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02977988). As there was some attrition and survey non-response during the trial, the sample size for each analysis in the present study is provided in the table pertaining to that analysis (those with missing data for a particular analysis were excluded from that analysis).

Measures

Applied Mindfulness Process Scale (AMPS)

A self-report measure to quantify the level at which individuals apply mindfulness skills in daily life and in response to stressors as skills are learned during the course of an MBI (M. Li et al., 2016). The 15-item measure asks participants to consider items over the past week on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 never to 5 almost always. The developers of the AMPS found support for three factors mapping to subscales they labeled decentering (e.g., “I observe my thoughts in a non-attached manner,” “see that my thoughts are not necessarily true”), positive emotion regulation (e.g., “notice pleasant things in the face of difficult circumstances,” “enjoy the little things in life more fully”), and negative emotion regulation (e.g., “let go of unpleasant thoughts and feelings,” “stop reacting to my negative impulses”). A list of all AMPS items is included in Supplementary Information. Participants completed the AMPS after intervention Ssessions 3, 6, 9, and 12 (every other week of the 6-week intervention). We summed scores for the full scale (composite score) and for each of the three subscales (i.e., decentering, positive emotion regulation, negative emotion regulation). To evaluate the extent to which mindfulness skills applied across the intervention period were associated with conceptually related constructs, we created aggregate, global scores for the AMPS and each of its subscales by taking the average of the summed AMPS or subscale scores obtained across all four assessments.

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire – Short Form (FFMQ-SF)

A self-report measure to quantify an individual’s tendency to be mindful in daily life over a 30-day period (Bohlmeijer et al., 2011). The 24-item measure asks participants to rate items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 never or very rarely true to 5 very often or always true. Items on the FFMQ-SF cover five dimensions of dispositional mindfulness: observing one’s internal and external experiences (e.g., “I pay attention to physical experiences, such as the wind in my hair or sun on my face”), describing one’s internal experiences (e.g., “I am good at finding words to describe my feelings”), acting with awareness rather than on automatic pilot (e.g., “I do jobs or tasks automatically without being aware of what I’m doing”), taking a non-judging stance towards one’s thoughts and feelings (e.g., “I tell myself that I shouldn’t be thinking the way I’m thinking”), and non-reactivity to one’s inner experiences (e.g., “When I have distressing thoughts or images, I don’t let myself be carried away by them”). Participants completed the FFMQ-SF at baseline and post-intervention. We summed item scores to obtain a FFMQ-SF score. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient (range) was 0.77 – 0.80, and the McDonald’s omega reliability coefficient (range) was 0.81–0.83. We also computed a change score (∆ FFMQ-SF) by subtracting baseline FFMQ-SF from the post-intervention score.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS)

A self-report measure to quantify the frequency with which an individual experiences difficulties regulating emotions over a 30-day period (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). The 36-item measure asks participants to rate items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 never to 5 almost always. Items on the DERS cover six factors, including nonacceptance of emotions (e.g., “When I’m upset, I feel guilty for feeling that way”), difficulty engaging in goal-oriented behavior (e.g., “When I’m upset, I have difficulty concentrating“), difficulty with impulse control (e.g., “When I’m upset, I lose control over my behaviors”), lack of awareness of emotions (e.g., “I’m attentive to my feelings”), limitations in effective emotion regulation strategies (e.g., “When I’m upset, my emotions feel overwhelming”), and lack of clarity of emotions (e.g., “I have no idea how I am feeling”). Participants completed the DERS at baseline and post-intervention. We summed item scores at each assessment to obtain a composite DERS score. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient at both time points was 0.95, and the McDonald’s omega reliability coefficient (range) was 0.95–0.96.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10)

A self-report measure used to quantify perceived stress by how often, over a 30-day period, the individual had specific stress-related thoughts and feelings (Cohen et al., 1983). The 10-item scale asks participants to rate items on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 never to 4 very often. Example items include “How often did you feel nervous or stressed?” and “How often did you feel that difficulties were piling so high that you could not overcome them?” Participants completed the PSS-10 at study baseline and post-intervention completion. We summed item scores at each assessment to obtain a composite PSS-10 score. Several recent studies utilizing bifactor modeling have demonstrated support for the use of such a composite (Lee & Jeong, 2019; Reis et al., 2019; Wu & Amtmann, 2013). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient (range) was 0.81–0.84, and the McDonald’s omega reliability coefficient (range) was 0.83–0.85.

Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS)

A measure of self-report used to quantify substance use cravings by the frequency, intensity, and duration of the individual’s cravings for substances as well as their ability to resist substance use over the past 30 days (Flannery et al., 1999). While the original PACS targets alcohol use cravings, we revise the wording to also capture cravings for other drugs. The five-item scale asks participants to rate each item on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 none/never to 6 unable to resist/all the time. Example items include “At its most severe point how strong was your craving?” and “How much time have you spent thinking about doing drugs or drinking?” Participants completed the PACS at baseline and post-intervention completion. We took the average of item scores at each assessment to obtain a PACS score. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient (range) was 0.90 – 0.92, and the McDonald’s omega reliability coefficient was 0.92–0.93.

Class Attendance

Attendance is a measure of exposure to an intervention (Amaro & Black, 2021). Attendance at each of 12 MMWR sessions was observed by study staff and recorded via a sign-in sheet. Participants were instructed to sign at the start of the session. If signatures were missing, research staff consulted with group facilitators to confirm the absence.

Mindfulness Practice Effort

We used a self-report practice log to quantify engagement in mindfulness practice. Participants reported how often they engaged in formal and informal mindfulness practices outside of study intervention sessions. The 16-item practice log asked participants on a 6-item Likert-scale how often (i.e., 0 = never; 1 = less than once a day; 2 = once a day; 3 = two times a day; 4 = three times a day; 5 = four or more times a day) they engaged in specific practices over the prior week. Formal practices included sitting meditation and loving kindness meditation, and informal mindfulness practices included noticing one’s own breathing, and noticing cravings without judgement. Practice logs were collected at intervention Sessions 3, 6, 9, and 12 concordant with the AMPS administration. We took the mean of item scores at each of the four sessions, and computed a global average that aggregates the four sessions of assessment. We interpreted effort as a behavioral measure of mindfulness meditation.

Clinical and Sociodemographic Variables

Age, race/ethnicity, education, and substance use were self-reported at baseline. SUDs and mental health conditions were diagnosed by a behavioral health clinician at the treatment site at intake according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria (5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Data Analyses

Measure Reliability

The consistency and stability of the composite AMPS as well as each of its three subscales (decentering, positive emotion regulation, negative emotion regulation) were assessed with measures of test-retest (Spearman’s rank-order correlations; Spearman’s ρ) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha, McDonald’s omega, and inter-item correlation) reliability. Analyses were conducted in Stata version 16.

Test-retest reliability refers to the consistency of observed scores when a measure is administered repeatedly over time (Guttman, 1945). For test-retest reliability, we correlated the composite AMPS score or subscale scores at each of four assessments with scores at all other periods. Spearman’s correlations were used due to the non-normality of AMPS and AMPS subscale score distributions at several time points (Table 2). A Spearman’s correlation of 0.10 was considered a small correlation, 0.40 was considered a moderate correlation, and 0.70 was considered a large correlation in line with established standards (Schober et al., 2018).

Internal consistency reliability refers to the degree to which items in a scale measure the same underlying construct (Henson, 2001). For internal consistency reliability, scores were calculated with individual item responses for the composite AMPS and each subscale at each time point. For Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega, a score of 0.80 was considered adequate reliability in line with established standards (Doval et al., 2023). Inter-item correlation, a measure of the correlation between each item and all other items in the scale or subscale, was obtained using the alpha command in Stata. In line with established standards, an average inter-item correlation for all scale or subscale items of 0.20–0.40 was considered optimal, less than 0.20 was low (i.e., items may not represent the same domain) and above 0.40 was high (i.e., items may not represent the full breadth of the domain) (Piedmont, 2014).

Nomological Validity

A measure has nomological validity if it behaves as expected within a system of related constructs (Newton & Shaw, 2014). We assessed the degree to which the composite AMPS and each subscale correlated with conceptually related constructs (mindfulness practice effort, class attendance, FFMQ-SF, PSS-10, DERS, and PACS) using Pearson correlations in Stata. We correlated composite AMPS and subscale scores from each session with mindfulness practice effort measured at that same session. We also correlated composite AMPS and subscale scores at Sessions 3 and 12 with FFMQ-SF scores from the most proximal assessment period (at baseline and post-intervention, respectively). We correlated a global AMPS and global subscale scores (the average of composite AMPS or subscale summed scores at all four time points) with FFMQ-SF, PSS-10, DERS, and PACS measured post-intervention. We used these global scores to represent an aggregate of applying learned skills during the intervention. Finally, we computed correlations between global scores and change in FFMQ-SF during the intervention (∆ FFMQ-SF), mindfulness practice effort during the intervention, and total number of MMRW classes attended during the intervention with an expectation of a positive correlation. Again, 0.10 was considered a small correlation, 0.40 was considered a moderate correlation, and 0.70 was considered a large correlation (Schober et al., 2018).

Incremental Validity

A measure has incremental validity when it improves one’s ability to predict conceptually related phenomenon over existing measures (Haynes & Lench, 2003). We evaluated the incremental validity of the AMPS using a sequence of linear regressions modeling the association between global AMPS (average of summed, composite AMPS scores at all four time points) and PSS-10, DERS, and PACS immediately after completion of the intervention, and tested whether these relations change while statistically controlling for mindfulness disposition, mindfulness practice effort, and class attendance. We conducted separate linear regression models for the PSS-10, DERS, and PACS as the dependent variable at post-intervention. Linear regression models utilized the ordinary least squares estimation method. For each dependent variable, we estimated three models: a null model (AMPS only), a model controlling for ∆ FFMQ-SF only, and a model controlling for ∆ FFMQ-SF, mindfulness practice effort, and MMWR class attendance, for a total of nine models. We included baseline score on the dependent variable in all models (including the null models) as a covariate. We checked whether our final PSS-10, DERS, and PACS models (those including all mindfulness practice covariates) adhered to assumptions of linear regression using the performance package in R version 4.2.2 (Lüdecke et al., 2021). Assumption checks included a visual check for linearity of residuals, a Shapiro-Wilk test for normality of residuals, a Durbin-Watson test for independence of residuals, a Breusch-Pagan test for homoscedasticity of residuals, a variance inflation factor calculation to test for multicollinearity, and a Cook’s Distance calculation to test for influential observations (Breusch & Pagan, 1979; Cook, 2000; Das & Imon, 2016; Durbin & Watson, 1971; Thompson et al., 2017). Model output included standardized coefficients (β) and effect size (partial eta squared), where an effect size of 0.01 was considered a small effect, 0.06 was considered a moderate effect, and 0.14 was considered a large effect (Richardson, 2011).

Results

Reliability Assessment

Table 3 provides measure reliability estimates for the composite AMPS and its subscales at Sessions 3, 6, 9, and 12. The interval between each time point was approximately 2 weeks and the items on the AMPS ask participants to consider the past 7 days. Test-retest reliability correlations between composite AMPS or AMPS subscale scores were all small-to-moderate in magnitude (ρ range = 0.28–0.74). Internal consistency reliability estimates met established standards for reliability (Cronbach’s alpha range = 0.80–0.97; McDonald’s omega range = 0.81–0.97). While some methodologists began to recommend the use of McDonald’s omega, recent work continues to favor the more commonly used Cronbach’s alpha (Doval et al., 2023; Hayes & Coutts, 2020). Thus, we provide both estimates of internal consistency reliability in Table 3.

Mean inter-item correlation estimates were of a large magnitude for the composite AMPS (range = 0.52–0.67), decentering (range = 0.44–0.62), positive emotion regulation (range = 0.67–0.75), and negative emotion regulation (range = 0.55–0.72), suggesting items may be redundant or there may be aspects of each construct not captured by the scale/subscale (Piedmont, 2014). In Supplementary Information, we include inter-item correlations at the individual item level; these were sometimes higher between items of different subscales compared with items from the same subscale, and correlations sometimes shifted between response periods.

Nomological Validity Assessment

Table 4 provides correlations between single-session AMPS or subscale scores with mindfulness variables (FFMQ-SF and mindfulness practice effort) at the same practice session or most proximal assessment. Single-session composite AMPS and subscale scores were positively correlated at a small-to-moderate magnitude with mindfulness practice effort at the same session (r range = 0.21–0.68, p < 0.01 for all correlations except decentering with mindfulness practice at Ssession 6) and FFMQ-SF at the most proximal assessment period (r range = 0.18–0.39, p < 0.05 for all correlations except decentering at Session 3 with FFMQ-SF at baseline). Table 5 provides the intercorrelations between the aggregate global AMPS or global subscale score (average of summed scores across four time points) and conceptually related constructs measured at post intervention (FFMQ-SF, PSS-10, DERS, and PACS) or aggregated during the intervention period (MMWR class attendance and mindfulness practice effort). The global scores were positively correlated with MMWR class attendance (r range = 0.30–0.39, p < 0.01, small magnitude) and mindfulness practice effort (r range = 0.61–0.66, p < 0.01, moderate magnitude) throughout the intervention. The scores were positively correlated with the FFMQ-SF measured immediately post-intervention (r range = 0.38–0.45, p < 0.01, small-to-moderate magnitude), and inversely correlated with the PSS-10 (r range = −0.27 to −0.31, p < 0.05, small magnitude) and DERS (r range = −0.41 to −0.49, p < 0.01, moderate magnitude) at post-intervention. Neither the global AMPS nor global subscale scores correlated with change in FFMQ-SF (∆ FFMQ-SF).

Incremental Validity Assessment

Table 6 provides linear regression model estimates for three psychological construct measures at post-intervention: PSS-10, DERS, and PACS. Each is regressed on the global AMPS (average of summed scores across four time points) in three iterations: null models (including global AMPS only), models controlling for the ∆ FFMQ-SF, and models controlling for the ∆ FFMQ-SF, mindfulness practice effort, and MMWR class attendance. For the null models, AMPS was associated with DERS (β = −0.4, p < 0.01) and PSS (β = −0.26, p < 0.05) post-intervention. Results of the models with all mindfulness practice covariates indicate the AMPS explained additional variance only in the DERS at immediate post-intervention (β = −0.32, p < 0.05) with a moderate effect size (partial eta squared = 0.08). Models with all mindfulness practice covariates generally adhered to assumptions of linear regression, although the Shapiro-Wilk test detected possible non-normality of residuals for the DERS model; p < 0.001. Thus, we re-ran the model after performing an inverse square root transformation on the DERS variable. The model with the transformed DERS variable adhered to all assumptions of linear regression, and AMPS remained a significant predictor (β = 0.36, p < 0.001). While regression coefficients for transformed outcome variables are challenging to interpret, given the inverse transformation the coefficient implies a negative association between AMPS and raw DERS scores (i.e., those with higher AMPS scores had lower DERS scores), and the effect size for AMPS was similar in magnitude as in the model with the non-transformed DERS variable (partial eta squared = 0.10).

Discussion

The AMPS was created to assess the degree to which an individual applies mindfulness practice skills in daily life as those skills are learned and developed during the process of an MBI course. In the original psychometric study of the AMPS with a homogenous and healthy sample of mind-body practitioners, the instrument displayed adequate standards for reliability and nomological validity, that is, scores correlated with trait mindfulness and psychological well-being and negatively with perceived stress and psychological distress (Li et al., 2016). However, there remained gaps in knowledge regarding the psychometric properties of the AMPS among a clinical sample not familiar with mindfulness. The objective of our analysis was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the AMPS in a clinical sample of women diagnosed with SUD and receiving a structured MBI. We hypothesized that the AMPS would meet minimum standards for reliability in this sample and explain additional variance in the conceptually related target mechanisms of MBIs beyond the effect of established mindfulness measures.

In accordance with prior measure evaluations, we found support for test-retest reliability and internal consistency reliability among our racially and ethnically diverse, clinical sample (Li et al., 2016). The AMPS evidenced mostly sound test-retest reliability across four assessments spanning a 6-week intervention period, though some correlations were small in magnitude. It is possible test-retest reliability is influenced by various sources of error, namely the effect of learning and skill development during the MMWR program and the use of the complete measure in every assessment (Carmines & Zeller, 1979). Future research on the AMPS can address this by administering different versions of the assessment to the same individuals (i.e., a test of parallel forms reliability; Heale & Twycross, 2015). Measures of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega) for each assessment period suggest that items in the AMPS relate with one another in this clinical sample. However, the mean inter-item correlation scores for the AMPS and its subscales were high relative to established standards, suggesting there may be some redundancy among items or there may be additional aspects of mindfulness practice not captured by the measure (Piedmont, 2014). Future work should therefore explore whether additional items are needed to more comprehensively capture the application of mindfulness training among novice meditators. Further, individual item correlations were sometimes higher between items of different subscales compared with items from the same subscale and shifted between response periods (see Supplementary Information).

While it may have been fruitful to explore the factor structure of the AMPS, the sample size was insufficient for such analyses (Boateng et al., 2018). Some of our reliability results suggest the three-factor model reported in prior work with experienced mindfulness practitioners may not apply in clinical, novice practitioner samples (Li et al., 2016). In fact, we propose it is likely items may not universally load on factors during the individualized and dynamic process of teaching and learning mindfulness practice. That is, for novice participants during skill development, one’s understanding and interpretation of mindfulness practice likely shift over time as teachers variably and dynamically introduce new language and connect new practices with previous ideas. Measurement invariance should be fully explored with the AMPS in larger clinical samples receiving training in mindfulness practice (Boateng et al., 2018).

We found support for nomological validity as the AMPS and its subscales correlated with conceptually related psychological constructs pertinent to recovery from SUD (e.g., perceived stress, difficulties in emotion regulation) measured immediately after the intervention. Our finding that AMPS and subscale scores were not correlated with substance use craving is surprising, given MBIs’ reported effect in reducing craving (Priddy et al., 2018). Our evaluation suggests the AMPS as a measure of mindfulness applied as a skill to address stressful circumstances in daily living may occupy a unique place relative to other mindfulness measures including mindfulness practice effort and disposition (Sauer et al., 2013). Scores on the AMPS and its subscales were moderately correlated with mindfulness practice effort and class attendance (with the exception of decentering and mindfulness practice at a single session assessment), as well as with scores on the FFMQ immediately post-intervention, suggesting the AMPS is measuring something related but not identical to existing measures. This is in line with conceptions of mindfulness training involving multiple, related components: the application of mindfulness practices as a behavioral activity, as well as alterations in one’s dispositional capacities towards mindfulness (Chiesa et al., 2014; Goleman & Davidson, 2017). It makes sense that AMPS would be significantly but not perfectly correlated with other mindfulness measures (FFMQ-SF, mindfulness practice effort, and MMRW class attendance), as these measures capture mindfulness-related constructs, but the AMPS was developed specifically to measure a novel construct not captured by existing measures (i.e., mindfulness practice processes). However, neither AMPS nor subscales were correlated with change in dispositional mindfulness (∆ FFMQ-SF) during the intervention, perhaps suggesting it takes longer than 6 weeks of applying mindfulness to see changes in mindfulness disposition. Participant self-reports of dispositional mindfulness may actually decrease after an individual gains more experience with mindfulness practices because they might become increasingly aware of what mindfulness entails and better at noticing when they are not exhibiting mindfulness (Grossman, 2011). This is similar to a person learning piano, overestimating their skill prior to the first lesson, and increasingly realizing their inability to perform. This limitation of conventional measures may partially explain the lack of correlation between FFMQ and AMPS scores. Such dissensus points to the importance of including AMPS as a behavioral measure of mindfulness processes.

Correlations involving each AMPS subscale were generally not distinct from correlations involving other subscales or the composite AMPS. Given this and points on reliability and factor structure during the process of skill development, the composite AMPS may be most useful to capture the skill acquisition among novice meditators. That is, the composite AMPS might most comprehensively capture the application of practices—even if these differ between novice meditators or within the same individual over time. Thus, we focused on the composite AMPS in our test of incremental validity. Results here suggest AMPS may be especially relevant for capturing difficulties with emotion regulation after an MBI, as AMPS explained additional variance in DERS scores beyond conventional mindfulness measures and when controlling for DERS at baseline. Indeed, items on the AMPS aim to capture mindfulness skills applied in the service of regulating emotion. Given that emotion regulation is often an explicit target of MBIs, our findings suggest the AMPS may be a useful measure in MBI studies targeting clinical disorders involving emotion dysregulation such as SUD as well as focusing on emotion dysregulation as a target mechanisms or outcome (Garland et al., 2014). While the AMPS was again not associated with craving in tests of incremental validity, changes in dispositional mindfulness (∆ FFMQ-SF) were negatively associated with craving (that is, increases in dispositional mindfulness were associated with lower craving). The FFMQ may have more utility in predicting craving compared to AMPS. Perhaps the experience of craving is relatively intractable, and it is less impacted by instances of mindfulness practices captured by the AMPS and more so to changes in one’s disposition captured by the FFMQ.

As an evaluation of the AMPS in a diverse sample with and SUD, our investigation provides support that the AMPS yields unique scores representing mindfulness applied in daily living coincident with an MBI. The AMPS broadens the ability of clinical researchers to capture behavioral aspects associated with therapeutic change that are distinct from conventional measures of practice quantity and mindfulness disposition. Findings suggest the AMPS meets or exceeds minimum psychometric standards in a clinical sample of women with SUD, and the measure yields predictive value for emotion dysregulation, a common target of MBIs.

Limitations and Future Research

Given aforementioned limitations due to sample size, future factor analytic work involving larger samples of novice meditators with clinical disorders is necessary. In particular, a bifactor model should be tested among such a sample to determine whether items load better on a single factor versus the three factors determined in prior work, and tests of measurement invariance should be utilized to determine whether factor loadings shift over the course of skill development (Boateng et al., 2018; M. Li et al., 2016). We note several additional methodological limitations of our work. Our results may be influenced by common methods bias, as subjects were surveyed on their own perceptions on multiple constructs. This can produce spurious correlations between these constructs due to response styles, social desirability, and priming effects, which are themselves independent from the true correlations among the constructs being measured (Podsakoff et al., 2012). As a secondary analysis increases researcher degrees of freedom, there is the possibility of inflated type I errors (false positive results). Thus, we report statistical significance for all results at both 0.05 and a more conservative 0.01 alpha level, and the majority of results remain significant at the 0.01 level. Some features of our study also limit inference of results to certain clinical populations. Our data are limited to a single SUD residential clinic site of women, thus restricting inference of scale utility to clinical conditions outside of addictions as well as treatment programs for men. Similarly, while the racial and ethnic diversity is a strength of our study, findings may not generalize to groups outside of Latina and Black women. A majority of our sample report other psychiatric conditions comorbid with SUD and this may possibly allow the argument supporting the use of AMPS in samples with either SUD or other mental health disorders. Although complicating a point on singular diagnosis, this sample feature is a strength given the prevalent comorbidities between SUD and psychiatric disorders. Still, future research should test the AMPS in additional racial and ethnic minority groups as well as those with varying clinical disorders that are targets of MBIs.

Data Availability

All data are available at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/9jgxs/).

References

Amaro, H., & Black, D. S. (2017). Moment-by-moment in women’s recovery: randomized controlled trial protocol to test the efficacy of a mindfulness-based intervention on treatment retention and relapse prevention among women in residential treatment for substance use disorder. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 62, 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2017.09.004

Amaro, H., & Black, D. S. (2021). Mindfulness-based intervention effects on substance use and relapse among women in residential treatment: a randomized controlled trial with 8.5-month follow-up period from the moment-by-moment in women’s recovery project. Psychosomatic Medicine, 83(6), 528–538. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000907

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/CLIPSY.BPG015

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

Benson, H., Beary, J. F., & Carol, M. P. (1974). The relaxation response. Psychiatry, 37(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1974.11023785

Black, D. S. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions: an antidote to suffering in the context of substance use, misuse, and addiction. Substance Use & Misuse, 49, 487–491. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2014.860749

Black, D. S., & Amaro, H. (2019). Moment-by-moment in women’s recovery (MMWR): mindfulness-based intervention effects on residential substance use disorder treatment retention in a randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 120, 103437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103437

Black, D. S., Sussman, S., Johnson, C. A., & Milam, J. (2012). Psychometric assessment of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) among Chinese adolescents. Assessment, 19(1), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111415365

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

Bohlmeijer, E., Ten Klooster, P. M., Fledderus, M., Veehof, M., & Baer, R. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment, 18(3), 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111408231

Breusch, T. S., & Pagan, A. R. (1979). A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation Econometrica. Journal of the Econometric Society 47(5) 1287-1294.https://doi.org/10.2307/1911963

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985642

Carmody, J., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7

Chiesa, A., Anselmi, R., & Serretti, A. (2014). Psychological mechanisms of mindfulness-based interventions: what do we know? Holistic Nursing Practice, 28(2), 124–148. https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0000000000000017

Chiesa, A., & Malinowski, P. (2011). Mindfulness-based approaches: are they all the same? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(4), 404–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/JCLP.20776

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

Cook, R. D. (2000). Detection of influential observation in linear regression. Technometrics, 42(1), 65–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/1268249

Das, K. R., & Imon, A. (2016). A brief review of tests for normality. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.12

Durbin, J., & Watson, G. S. (1971). Testing for serial correlation in least squares regression. III. Biometrika, 58(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2334313

Doval, E., Viladrich, C., & Angulo-Brunet, A. (2023). Coefficient alpha: the resistance of a classic. Psicothema, 35(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2022.321

Flannery, B. A., Volpicelli, J. R., & Pettinati, H. M. (1999). Psychometric properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 23(8), 1289–1295. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1530-0277.1999.TB04349.X

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, R., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2015). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: a process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 26(4), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294

Garland, E. L., Froeliger, B., & Howard, M. O. (2014). Mindfulness training targets neurocognitive mechanisms of addiction at the attention-appraisal-emotion interface. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4, 173. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00173

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011

Goleman, D., & Davidson, R. J. (2017). Altered traits: science reveals how meditation changes your mind, brain, and body. Penguin.

González-Blanch, C., Medrano, L. A., O’Sullivan, S., Bell, I., Nicholas, J., Chambers, R., Gleeson, J. F., & Alvarez-Jimenez, M. (2022). Psychometric properties of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) in a first-episode psychosis sample. Psychological Assessment, 34(2), 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001077

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Grossman, P. (2011). Defining mindfulness by how poorly I think I pay attention during everyday awareness and other intractable problems for psychology’s (re) invention of mindfulness: comment on Brown. Psychological Assessment, 23(4), 1034–1040. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022713

Guttman, L. (1945). A basis for analyzing test-retest reliability. Psychometrika, 10(4), 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02288892

Hayes, A. F., & Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But…. Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

Haynes, S. N., & Lench, H. C. (2003). Incremental validity of new clinical assessment measures. Psychological Assessment, 15(4), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.15.4.456

Heale, R., & Twycross, A. (2015). Validity and reliability in quantitative studies. Evidence-Based Nursing, 18(3), 66–67. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102129

Henson, R. K. (2001). Understanding internal consistency reliability estimates: a conceptual primer on coefficient alpha. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34(3), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2002.12069034

Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/CLIPSY.BPG016

Lee, B., & Jeong, H. I. (2019). Construct validity of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) in a sample of early childhood teacher candidates. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(1), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750573.2019.1565693

Li, M. J., Black, D. S., & Garland, E. L. (2016). The Applied Mindfulness Process Scale (AMPS): a process measure for evaluating mindfulness-based interventions. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.027

Li, W., Howard, M. O., Garland, E. L., McGovern, P., & Lazar, M. (2017). Mindfulness treatment for substance misuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 75, 62–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.008

Lüdecke, D., Ben-Shachar, M. S., Patil, I., Waggoner, P., & Makowski, D. (2021). performance: an R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(60). https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03139

Piedmont, R. L. (2014). Inter-item correlations. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 3303–3304). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1493

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Priddy, S. E., Howard, M. O., Hanley, A. W., Riquino, M. R., Friberg-Felsted, K., & Garland, E. L. (2018). Mindfulness meditation in the treatment of substance use disorders and preventing future relapse: neurocognitive mechanisms and clinical implications. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 9, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S145201

Reis, D., Lehr, D., Heber, E., & Ebert, D. D. (2019). The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10): evaluation of dimensionality, validity, and measurement invariance with exploratory and confirmatory bifactor modeling. Assessment, 26(7), 1246–1259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0875-9

Richardson, J. T. E. (2011). Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.12.001

Santorelli, S. F., Kabat-Zinn, J., Blacker, M., Meleo-Meyer, F., & Koerbel, L. (2017). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) authorized curriculum guide. In Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society (CFM). University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Sauer, S., Walach, H., Schmidt, S., Hinterberger, T., Lynch, S., Büssing, A., & Kohls, N. (2013). Assessment of mindfulness: review on state of the art. Mindfulness, 4(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0122-5

Schober, P., Boer, C., & Schwarte, L. A. (2018). Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 126(5), 1763–1768. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864

Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z., & Williams, J. M. G. (1995). How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)E0011-7

Thompson, C. G., Kim, R. S., Aloe, A. M., & Becker, B. J. (2017). Extracting the variance inflation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(2), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2016.1277529

Watson-Singleton, N. N., Walker, J. H., LoParo, D., Mack, S. A., & Kaslow, N. J. (2018). Psychometric evaluation of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in a clinical sample of African Americans. Mindfulness, 9(1), 312–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0776-0

Newton, P., & Shaw, S. (2014). Validity in educational and psychological assessment. Sage https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446288856

Wu, S. M., & Amtmann, D. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the Perceived Stress Scale in multiple sclerosis. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/608356

Funding

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium Funding support was provided by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01DA038648 to author DSB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SKS: co-designed and executed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. DSB: co-designed the study, supervised data analyses, and collaborated in writing and editing the final manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All study procedures were reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California, and the procedures followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

All participants provided informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 40 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saba, S.K., Black, D.S. Psychometric Assessment of the Applied Mindfulness Process Scale (AMPS) Among a Sample of Women in Treatment for Substance Use Disorder. Mindfulness 14, 1406–1418 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02144-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02144-1