Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this systematic review was to assess the current literature on mindfulness-based school interventions (MBSIs) by evaluating evidence across specific outcomes for youth.

Methods

We evaluated 77 studies with a total sample of 12,358 students across five continents, assessing the quality of each study through a robust coding system for evidence-based guidelines. Coders rated each study numerically per study design as 1 + + (RCT with a very low risk of bias) to 4 (expert opinion) and across studies for the corresponding evidence letter grade, from highest quality (“A Grade”) to lowest quality (“D Grade”) evidence.

Results

The highest quality evidence (“A Grade”) across outcomes indicated that MBSIs increased prosocial behavior, resilience, executive function, attention, and mindfulness, and decreased anxiety, attention problems/ADHD behaviors, and conduct behaviors. The highest quality evidence for well-being was split, with some studies showing increased well-being and some showing no improvements. The highest quality evidence suggests MBSIs have a null effect on depression symptoms.

Conclusions

This review demonstrates the promise of incorporating mindfulness interventions in school settings for improving certain youth outcomes. We urge researchers interested in MBSIs to study their effectiveness using more rigorous designs (e.g., RCTs with active control groups, multi-method outcome assessment, and follow-up evaluation), to minimize bias and promote higher quality—not just increased quantity—evidence that can be relied upon to guide school-based practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many preschool, elementary, and high school students experience problems related to anger, anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem (Barnes et al., 2003; Fisher, 2006; Langer et al., 2015; Mendelson et al., 2010; Rempel, 2012) that negatively influence their academic and social development (Leigh & Clark, 2018; Maughan et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2015) and have lasting effects on their well-being (Steger & Kashdan, 2009). Schools can play a pivotal role in promoting students’ mental health and their social, emotional, and behavioral development (Barnes et al., 2003; Fisher, 2006; Mendelson et al., 2010). To address these challenges, many schools have adopted mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs). Studies conducted over the past 15 years have examined the impact of MBIs on mental health, educational performance, and related outcomes in children and adolescents (Kallapiran et al., 2015; Meiklejohn et al., 2012).

Mindfulness is the process by which we “pay attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and nonjudgmentally” (Baer, 2003; Roeser, 2014). Originally adapted for adults, practicing mindfulness typically includes meditation exercises and bringing mindful awareness to daily activities, such as eating and walking. These practices are intended to foster purposeful focused attention, coupled with a nonjudgmental attitude toward moment-to-moment experience (Kabat‐Zinn, 2003). Mindfulness-based interventions target many aspects of well-being, resiliency, and mental health by cultivating a present-centered awareness and acceptance (Fjorback et al., 2011; Gawrysiak et al., 2018; Greeson, 2009; Khoury et al., 2013; Roeser, 2014). In particular, emotion regulation has been the focus of much MBI research (Guendelman et al., 2017; Wisner, 2014). Individuals who have difficulty with emotion regulation have problems processing, experiencing, expressing, and managing emotions effectively (Chambers et al., 2009). Furthermore, the nonjudgmental awareness in mindfulness may facilitate a healthy engagement with emotions, allowing individuals to experience and express their emotions without under-engagement (e.g., experiential avoidance and thought suppression) or over-engagement (e.g., worry and rumination; Hayes & Feldman, 2004; Ivanovski & Malhi, 2007). Specifically, research indicates that MBI with adults can increase awareness of moment-to-moment experience and promote reflection, empathy, and caring for others (Hölzel et al., 2011). Mindfulness training with adults can also improve stress regulation, resilience, anxiety, and depression (Forkmann et al., 2014; Hofmann et al., 2010; Irving et al., 2009; Klatt et al., 2015; Li & Bressington, 2019; Marcus et al., 2003; Morton et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2007).

Despite extensive empirical support for mindfulness practice with adults, the question of whether MBI also benefits youth remain less clear, as far fewer studies examine mindfulness practice with school-aged children and adolescents (Caldwell et al., 2019; Greenberg & Harris, 2012; Zoogman et al., 2015). Mindfulness practices have gained recent worldwide popularity as a school-based intervention (Burke, 2010; Greenberg & Harris, 2012; Zenner et al., 2014). These mindfulness-based school interventions (MBSIs) target a host of outcomes, including increasing awareness, empathy, compassion, gratitude, perspective-taking, psychological flexibility, present centeredness, and self-regulation such as regulating behaviors, cognitions, and emotions (Bernay et al., 2016; Eva & Thayer, 2017; Hill & Updegraff, 2012; Moses & Barlow, 2006; Sapthiang et al., 2019; Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015). MBIs with youth have shown reductions in behavioral problems, affective disturbances, stress, and suicidal ideation as well as improvements in ability to manage anger, well-being, and sense of belonging (Carsley et al., 2018; Coholic et al., 2019; Felver et al., 2016; Murray et al., 2018). Empirical studies have also demonstrated improvements in attention skills, social skills, sleep quality, and reductions in somatic and externalizing symptoms (Beauchemin et al., 2008; Biegel et al., 2009; Bootzin et al., 2005; Britton et al., 2010; Napoli et al., 2005; Zylowska et al., 2008).

The practices incorporated in MBSIs include psychoeducation about emotions and mindfulness, as well as specific mindfulness exercises, including awareness of breath, mindful body scans, and awareness of thoughts, feelings, and sensations. MBSIs are often delivered in the context of whole class instruction (general population of students) or targeted intervention (at-risk or clinical populations; Kuyken et al., 2013; Napoli et al., 2005; Raes et al., 2014). In addition, MBSIs are offered in a variety of formats (i.e., delivered by the research team or teacher, as multi-session programs or brief single-session workshops, with a variety of activities and exercises included), which previous reviews have shown to impact the effectiveness of MBSIs (Bender et al., 2018; Carsley et al., 2018; Schonert-Reichl & Roeser, 2016; Semple et al., 2017).

Mindfulness practices targeting school-aged populations include developmentally appropriate adaptations for children and adolescents (Bostic et al., 2015; Carsley et al., 2018). For example, time for practices is shorter; they incorporate multiple sensory modalities into activities, and rely on simplified metaphors to communicate difficult concepts; and there is more time for explaining key concepts (Burke, 2010; Felver et al., 2013). Most MBSIs tested in schools are designed to increase resilience to stress and decrease depression and anxiety symptoms (Wisner, 2014). Early studies showed promising results in decreasing anxiety, fatigue, depressive symptoms, stress-related issues, and disorders for various conditions (Bei et al., 2013; Fjorback et al., 2011; Grossman et al., 2004; Piet & Hougaard, 2011; Piet et al., 2012). Furthermore, mindfulness training for youth has been shown to be efficacious for some neurocognitive, psychosocial, and psychobiological outcomes while also showing that MBIs are feasible and acceptable for youth in schools (Black, 2015). Although there have been studies examining outcomes of MBIs, there are limited reviews focused solely on school-based interventions. Additionally, it is important to examine which outcomes show promising results together with outcomes that are not improved through MBSIs. Previous reviews and meta-analyses examined the quantity and strength of the evidence but did not weigh this by the quality of the evidence according to research design. Thus, the present study addresses this gap in the literature by providing a systematic review that examines MBSIs on youth outcomes by quality of study design using evidence-based guidelines, which is key to advancing the field of MBSIs. Prior to turning to the present study, we first consider what is known from previous reviews of MBI with youth and in schools.

Several meta-analytic and systematic reviews include MBIs delivered across multiple settings, including schools. Previous reviews found that youth who practiced mindfulness have positive outcomes for cognitive performance, resilience to stress, mindfulness, executive functioning, attention, depression, anxiety, and negative behaviors (Chi et al., 2018; Dunning et al., 2019; Zenner et al., 2014). Following is a summary of ten published meta-analytic and systematic reviews that examined the use of MBIs for youth (Bender et al., 2018; Black, 2015; Carsley et al., 2018; Kallapiran et al., 2015; Klingbeil, Fischer, et al., 2017; Klingbeil, Renshaw, et al., 2017; Maynard et al., 2017; Semple et al., 2017; Zenner et al., 2014; Zoogman et al., 2015). First, it is important to note the types of primary studies that were included. One meta-analysis included single-case designs (Klingbeil, Fischer, et al., 2017), three included any group designs (Carsley et al., 2018; Klingbeil, Renshaw, et al., 2017; Zoogman et al., 2015), and one included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs; Kallapiran et al., 2015). Five systematic reviews included randomized control trials, nonrandomized control trials, case studies, cohort studies, and quasi-experimental designs (Bender et al., 2018; Black, 2015; Maynard et al., 2017; Semple et al., 2017; Zenner et al., 2014). The findings from these several reviews across study design types found that MBIs with youth improve cognitive and socio-emotional competencies, executive functions, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, rumination, internalizing problems, externalizing problems, prosocial skills, stress, physical health, well-being, perceptions of peer relations, mood, quality of life, academic achievement, disruptive behavior, and negative and positive emotions (Bender et al., 2018; Black, 2015; Carsley et al., 2018; Kallapiran et al., 2015; Klingbeil, Fischer, et al., 2017; Klingbeil, Renshaw, et al., 2017; Maynard et al., 2017; Semple et al., 2017; Zenner et al., 2014; Zoogman et al., 2015). Compared to MBIs in other settings, MBSIs have effects that are in the cognitive domain as well as in psychological measures of stress, coping, and resilience (Zenner et al., 2014). Furthermore, MBSIs appear to be more effective for decreases in negative mental traits (e.g., affective disturbances, anxiety) as opposed to increases in positive mental traits (e.g., positive affect, prosocial functioning; McKeering & Hwang, 2019). However, further research comparing the relative strength of MBSIs for improving different mental traits is needed, particularly research weighting evidence of these outcomes by study design.

These reviews indicate the need for future studies to examine the effects of MBI with youth and in schools on symptoms of psychopathology, to include more active controls as the comparison group to allow future meta-analyses to compare the effects of the intervention, and to examine potential moderators that potentially influence program effectiveness (e.g., length of program), as well as to investigate the additional benefit of incorporating mindfulness practices with other evidence-based practices.

Considering the findings from the previous meta-analyses and systematic reviews, there seems to be a clear pattern of evidence suggesting that MBIs are, on the whole, safe and effective for use with youth (generally) as well as in schools (specifically) for improving a host of valued outcomes. Although most of the outcomes in most reviews showed small to moderate positive effects, it is noteworthy that some reviews yielded null effects for some outcomes. For example, Maynard et al. (2017) found no effect for behavioral and academic outcomes; similarly, Zenner et al. (2014) found no effect for emotional problems. Therefore, further examination is needed on the consistency of positive outcomes from MBSIs. That said, it is also important to note that none of the previous reviews indicated harmful or iatrogenic effects.

Finally, previous reviews have not focused on grading the quality of evidence but instead produced the average effect sizes. Given that several reviews collapsed all the studies together, the evidential quality is mixed, which makes it challenging to know how strong the quality of evidence is that supports the outcomes (Bender et al., 2018; Black, 2015; Carsley et al., 2018; Klingbeil, Fischer, et al., 2017; Klingbeil, Renshaw, et al., 2017; Maynard et al., 2017; Semple et al., 2017; Zenner et al., 2014; Zoogman et al., 2015). Likewise, one review that only examined RCTs produced much higher quality evidence (Kallapiran et al., 2015). Since these reviews either collapsed all studies together or looked at RCT only, none of the reviews systematically considered the quality of evidence both across study designs and within RCTs.

To address the growing interest in MBSIs and to inform those choosing programs, we systematically reviewed published studies of MBSIs for youth in schools (cf. Felver et al., 2016; Zenner et al., 2014). Unlike prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses, our review sought to examine the quality of outcome evidence by research design, as well as the quantity of evidence across studies. Specifically, the first objective was to determine the quality of the evidence across diverse outcomes including well-being, self-compassion, social functioning, mental health, self-regulation and emotionality, mindful awareness, attentional focus, psychological and physiological stress, problem behaviors, academic performance, and acceptability. The second objective was to investigate the quantity of the evidence across studies. Finally, the quality and quantity combined was examined across studies to determine which outcomes are most robustly associated with MBSIs. We anticipate that findings from our systematic review would contribute to the literature by providing evidence-based recommendations to clinicians, educators, and school-based researchers on which specific outcomes can be reliably targeted with MBSIs.

Methods

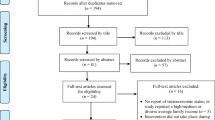

We identified studies through a systematic search of published articles of MBSIs with youth from the first available date until July 2021. The electronic databases searched were PsycINFO, EBSCOHost, MEDLINE, and CINAHL using terms related to MBSIs: (school-based mindfulness interventions subt.exact ((“mindfulness” OR “mindfulness-based interventions” AND “students” OR “preschool students” OR “elementary school students” OR “high school students” OR “adolescent” OR “schools” OR “adolescent development” OR “curriculum” OR “teachers” OR “educational programs” OR “middle school students” OR “elementary school teachers” OR “public school education”) NOT (“middle aged” OR “yoga” OR “college students” OR “young adult” OR “occupational stress” OR “parents” OR “chronic pain” OR “drug abuse” OR “neoplasms” OR “parenting” OR “substance-related disorders” OR “relapse prevention” OR “no terms assigned” OR “psychotherapy” OR “test construction” OR “health care services” OR “medical students” OR “mobile phones” OR “adult” OR “pregnancy”)) NOT su.exact (“Thirties (30–39 yrs)” OR “Middle Age (40–64 yrs)” OR “Aged (65 yrs & older)” OR “Very Old (85 yrs & older)”) NOT po.exact (“Outpatient” OR “Inpatient” OR “Animal”) AND PEER(yes) AND la.exact (“English”) NOT rtype.exact (“Comment/Reply” OR “Editorial” OR “Erratum/Correction” OR “Review-Book” OR “Letter”)). We found 352 articles through this initial search prior to eligibility coding (see Fig. 1 for the study selection process). In defining MBSIs, we selected only intervention studies that applied mindfulness meditation including dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan, 1993) and acceptance and commitment therapy (Strosahl & Wilson, 1999) as intervention frameworks since they both focus on acceptance and mindfulness.

Eligibility Ratings

Two coders assessed the eligibility of each journal article for inclusion based on the following criteria: (1) peer-reviewed journal article; (2) mindfulness-based school intervention, program, or strategies; (3) mindfulness outcome on teachers or children and/or implementation outcomes; (4) review paper on school-based mindfulness interventions; and (5) grade levels from kindergarten to 12th grade. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) studies focusing only on yoga, creativity, or other approaches not specific to mindfulness; (2) parent-based training on mindfulness; (3) clinic-based mindfulness interventions; (4) student age group ≥ 22 years (as students with disabilities in the USA can stay at school until they are 21 years old). Raters reached high inter-rater reliability (k = 0.98) in determining article eligibility. When raters disagreed, they discussed eligibility to reach a consensus.

Extracted Data from Studies

The following information was extracted from each study: (1) country, (2) sample characteristics (sample size, mean age [or age range if mean was not provided], percentage of males and females, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, whether children were of a special needs population), (3) information on the school level (preschool, elementary, middle, or high school), classroom setting (general education, special education, or alternative school; private or public), (4) type of intervention, (5) research design (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed), (6) evaluation design (e.g., RCT, pre-post), (7) the mediator (i.e., person who conducted the intervention), (8) the findings on outcomes (outcome measures), (9) outcome measure type (self-report, teacher-report, etc.), (10) control group, and (11) whether teacher training was provided. We believe it is important to consider the research and evaluation design of studies given the impact of methodological variations on the results. Furthermore, it is also essential to examine whether teacher training was provided since research shows that there are significant effects at follow-up when teachers are trained to deliver the program (Carsley et al., 2018).

Evidence Ratings

We used a robust system for grading recommendations in evidence-based guidelines (Harbour & Miller, 2001) to weigh evidence per study design in a two-step process. Using PRISMA 2020 as a guideline for our systematic review, we used the Harbour and Miller (2001) ratings to examine the level of evidence since PRISMA 2020 recommends assessing certainty in the body of evidence of an outcome (item #15 in the PRISMA checklist) and to present assessments of certainty in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed (item #22 in the PRISMA checklist). We are not using the Harbour and Miller guidelines in replacement of the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, but rather to grade evidence per study design in order to adhere to items #15 and #22 in the checklist. As such, we graded evidence based on the methodological rigor of studies to draw conclusions about the state of the science of MBSIs, and to make informed recommendations to advance the field. First, for all eligible articles, two authors independently assigned a numerical rating regarding the level of evidence for each article on a scale outlined by Harbour and Miller (2001), ranging from 1 + + (RCTs with a very low risk of bias), 1 + (RCTs with a low risk of bias), 1 − (RCTs with a high risk of bias), 2 + + (high-quality case–control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounds, bias, or chance, and a high probability that the relationship is causal), 2 + (well-conducted case–control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounds, bias, or chance and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal), 2 − (case–control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounds, bias, or chance and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal), 3 (non-analytic studies, e.g., case reports, case series) to 4 (expert opinion). We further specified criteria relating to risk of bias; for example, studies rated as 1 + + were RCTs that include at least three of the following criteria: competence/fidelity measurement, daily program implementer meetings, high participant attendance rate of 90% or higher, experienced program implementer, large sample size, 8 week or longer sessions, conducted follow-ups post-intervention. See Table 1 for the full grading system of recommendations in evidence-based guidelines. Using the breakdown mentioned above, ratings of studies included in this review ranged from 1 + + , 1 + , 1 − , 2 + + , 2 + , 2 − , 3 to 4, with high inter-rater reliability (k = 0.91). Raters discussed the six discrepant articles that they initially rated differently until they reached a consensus on the ratings.

Second, after determining the level of evidence for each article, a lettered grading system was applied based on a summary of the numbered ratings across studies: A (at least one RCT rated as 1 + + and directly applicable to the target population, or a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1 + directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results), B (a body of evidence including studies rated as 2 + + directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results), C (a body of evidence including studies rated as 2 + directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results), and D (a body of evidence including studies rated as 3 or 4). See Table 1 for the full grading system of recommendations in evidence-based guidelines with further specificity per evidence rating level. There was often variability in the numbered study ratings across outcome measures. The ultimate letter grade was determined by the inclusion of the number and number rating for high-quality studies (1 + + or 1 +), as described above. For example, for an outcome documented in two studies rated 1 + and 3, the letter grade would be Grade B as there was only one 1 + rated study (if there was a 1 + + rated study or a body of 1 + rated studies, the letter grade would be Grade A).

Results

Study Characteristics

We identified 77 eligible articles, which incorporated data from 12,358 students across 5 continents (North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Australasia). The breakdown of articles by methods was as follows: 9 qualitative, 49 quantitative, and 19 mixed methods. For the control group type, there were 28 active control groups, 21 passive control groups, and 28 without a control group. There were 35 elementary schools, 8 middle schools, 25 high schools, 1 preschool, 5 mixes of elementary and middle schools, and 3 mixes of middle and high schools. Given that all studies took place in a school setting, the data from this review are community-based instead of clinically based.

Forty-three percent of schools did not report on setting (e.g., public, private), but across those that did, 22% were private, 55% public, 5% alternative schools, 2% specialized school, and 16% a combination of schools. Fifty-two percent of children were female. Forty percent of studies did not include race/ethnicity, but those that did showed a diverse sample of 44% while 16% had homogenous samples within the study. Likewise, most studies did not include socioeconomic status (62%).

Regarding the person that mediated the treatment delivery, 3% did not report on the mediator, and of the studies that did report on the mediator, 40% were researchers, 28% teachers, 19% trained instructors, 7% mix of researcher and teacher/mindfulness instructor, 4% mindfulness instructors, and 3% counselors. In terms of teacher training on mindfulness interventions, only 31% reported teacher training. Furthermore, 50% reported using self-report as their outcome measure, 17% used both teacher report and self-report, 11% used a cognitive test with teacher or self-report, 8% used only teacher report, 8% used two or more measures, and 7% used other forms of outcome measure (i.e., computer tasks, cognitive tests, observation). See Online Resource 1 and Online Resource 2 for participant demographics, design, and methods for each of the 77 included studies.

Outcomes

Outcomes from studies of MBSIs fit into the following 11 categories determined by the main findings: (1) well-being, (2) self-compassion, (3) social functioning, (4) mental health, (5) self-regulation and emotionality, (6) mindful awareness, (7) attentional focus, (8) psychological and physiological stress, (9) problem behaviors, (10) academic performance, and (11) acceptability. For the purposes of this study, we conceptualized well-being as subjective well-being (i.e., feelings of contentment, life satisfaction) and mental health as per clinical descriptors (i.e., depression, anxiety, suicidality, trauma, eating disorders).

Summary of the Highest Quality Evidence Across Outcomes

In this systematic review of the quality of existing scientific literature base of MBSIs (see the “Methods” section, “Evidence Ratings”), the strongest level of evidence (“A Grade”) across outcomes indicated that MBSIs increased prosocial behavior, resilience, executive function, attention, and mindfulness, and decreased anxiety, attention problems/ADHD behaviors, and conduct behaviors, with evidence for well-being being split, with some studies showing increased well-being and some showing no improvements. As described in the “Methods” section, “A Grade” evidence comes from at least one RCT rated as 1 + + and directly applicable to the target population, or a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1 + directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results. See Table 1 for a description of each level of evidence, Table 2 for the outcomes per study, Fig. 2 for the breakdown of studies for each outcome by quality, and Online Resource 3 for the numbered list of included studies from Table 2.

Below we summarize the results per outcome type, highlighting “A Grade” and “B Grade” evidence, and noting any differences that were apparent between the overall summary of results from pre- to post-treatment incorporating all studies and when examining studies per research design (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed), evaluation design (RCT, pre-post, single case/series, etc.), or per control group type (active, passive, none). For a full breakdown of outcomes by these study characteristics and individual study evidence ratings, see Online Resource 4.

Well-being

Ten of the 77 eligible articles (13%) targeted well-being domain outcomes. Results were mixed regarding well-being outcomes, with 50% of studies showing improved well-being, and the rest showing no difference (42%) or lower well-being (8%). The mixed results from studies specifically studying well-being were both from “A Grade” evidence. No differences were apparent when examining results per research design, evaluation design, or control group type, except no pre-post design studies reported null improvements in well-being.

Self-compassion

Five of the 77 eligible articles (6%) targeted self-compassion domain outcomes. 100% of studies across research designs, evaluation designs, and control group types that examined self-compassion showed greater improvement. There was no “A Grade” evidence and the strongest evidence (“B Grade”) documented higher school self-concept.

Social Functioning

Fifteen of 77 eligible articles (19%) targeted social functioning domain outcomes. Most studies (86%) that examined social functioning found that MBSIs improved social relationships and social participation as well as reduced social bias, and those that found no improvements were of low evidence quality (“C and D Grades”). The highest quality of evidence documented (“A Grade”) was for improvements in prosocial behavior, followed by “B Grade” evidence showing improvements in empathy and social competence, and reduced prejudice towards outgroups. No differences were apparent when examining results per research design, evaluation design, or control group type, except no pre-post or passive design studies reported null improvements in social functioning.

Mental Health

Nineteen of 77 eligible articles (25%) targeted mental health domain outcomes. Most studies reported reduced depression and anxiety symptoms (71% and 80%, respectively). However, higher quality evidence (“A Grade”) shows no decrease in depression symptoms (compared to “B Grade” evidence that does show a decrease in depression symptoms). By contrast, studies showing no decrease in anxiety were of lower quality evidence (“C Grade”) compared to evidence showing a decrease in generalized anxiety disorder, worry, and panic disorder (“A Grade”), or anxiety symptoms (“B Grade”). The one study examining suicidality and the one study examining trauma each found reduced symptoms. Only one of the three studies examining eating disorder symptoms reported a reduction in symptoms. No differences were apparent when examining results per research design, evaluation design, or control group type, except no pre-post design studies reported null improvements in mental health.

Self-regulation and Emotionality

Thirty-one of 77 eligible articles (40%) targeted self-regulation and emotionality domain outcomes. Most studies (97%) in this category reported improved self-regulation and emotionality across research designs, evaluation designs, and control group types, except for one study of “C Grade” evidence that found no change in negative affect. No differences were apparent when examining positive vs. null improvement studies in terms of research design, evaluation design, or control group type. For the self-regulation category, the highest quality evidence (“A Grade”) documented improvements in resilience and executive function, followed by “B Grade” evidence showing improvements in self- and emotion regulation, coping skills, and cognitive control, as well as more frequent relaxed states at school. For the emotionality category, the highest quality studies (“B Grade”) documented higher positive moods and lower negative feelings.

Mindful Awareness

Eleven of 77 eligible articles (14%) targeted mindful awareness domain outcomes. All studies documented improved perspective-taking and having a positive outlook, and most (73%) documented improvements in mindfulness; however, evidence showing no improvements in mindfulness was of a lower quality (“C Grade”). No differences were apparent between positive and null improvement studies when examining results per research design, evaluation design, or control group type. The strongest evidence (“A Grade”) showed improvements in mindfulness, followed by “B Grade” evidence showing increased awareness of thoughts, feelings, emotions, and bodily sensations, being more present in life as well as decreased mind-wandering.

Attentional Focus

Twenty of 77 eligible articles (26%) targeted attentional focus domain outcomes. Most studies (95%) showed improvements in attention and reduced impulsivity across research designs, evaluation designs, and control group types, except one study finding no effects in task-shifted facilitation; however, evidence showing no improvements was of a lower quality (“C Grade”). The highest quality evidence (“A Grade”) found increased attention, and decreased attention problems and ADHD behaviors, followed by “B Grade” evidence showing increased concentration, and decreased distractibility and impulsivity.

Psychological and Physiological Stress

Fifteen of 77 eligible articles (19%) targeted psychological and physiological stress domain outcomes. Overall, most studies (73%) showed that MBSIs decreased psychological and physiological stress. Specifically for psychological stress, eight studies showed a reduction in stress (“B Grade” evidence), one study (7%) showed a null effect on stress (“C Grade” evidence), and two studies (13%) showed an increase in psychological stress (“D Grade” evidence). Specifically for physiological stress, four studies showed a reduction in stress (“B–D Grades” evidence) and one study showed an increase in stress (“B Grade” evidence). There was no “A Grade” evidence for this domain, and regarding research designs, evaluation designs, and control group types, no studies with active control groups found null/negative effects on psychological stress.

Problem Behaviors

Nine of 77 eligible articles (12%) targeted problem behavior domain outcomes. All studies reported a reduction in problem behaviors across research designs, evaluation designs, and control group types, including reduced aggression, disruptive behaviors, conduct behavior, and externalizing problems. The highest quality evidence (“A Grade”) showed a decrease in conduct behavior, followed by “B Grade” evidence showing a decrease in aggression.

Academic Performance

Sixteen of 77 eligible articles (21%) targeted academic performance domain outcomes. In most studies (94%) across research designs, evaluation designs, and control group types, MBSIs improved academic performance. One study found null improvements in reading fluency, so this was characterized as “D Grade” evidence. There was no “A Grade” evidence for this domain. The strongest evidence (“B Grade”) documented specific improvements in academic performance, auditory-verbal memory, GPA, math performance, math score, and social studies score, as well as an increase in positive attitudes towards academic subjects and lower test anxiety.

Acceptability

Only four of 77 eligible articles (5%) examined the acceptability of MBSIs, with all finding that they were highly acceptable; however; this evidence was of “C and D Grades.” There was no “A or B Grade” evidence reported for this domain.

Discussion

Our findings on the highest quality of evidence on MBSIs (“A Grade”) are consistent with previous studies on adults which have documented increased prosocial behavior, resilience, executive function, attention, and mindfulness, and decreased anxiety, attention problems/ADHD behaviors, and conduct behaviors (e.g., Goldberg et al., 2021; Guendelman et al., 2017; Hofmann et al., 2010; Hoge et al., 2013; Kemeny et al., 2012; Ramasubramanian, 2017; Rogers, 2013). In addition, these results are in line with recent studies where MBIs have demonstrated therapeutic effects targeting these mental health outcomes with youth in both clinical and school settings (Borquist-Conlon et al., 2019; Dunning et al., 2019; Renshaw et al., 2017).

Unlike in previous reviews, by examining the evidence grade per outcome measure, it is evident that there is a true split in evidence on well-being outcomes, with some high-quality evidence showing increased well-being and some other high-quality evidence showing no improvements (both “A Grade” evidence). When considering the studies rated as 1 + + (the highest evidence level), the positive effect study included middle school students from private schools and the null effect study included elementary school students from public schools; therefore, the difference in outcomes may relate to resources or student age groups. Further research is needed to elucidate this issue. Moreover, our re-examination of the evidence per evidence grades has highlighted that MBSIs have a null effect on depression symptoms (as per “A Grade” evidence).

Findings on well-being and depression are in contrast with prior reviews examining adults, where there are many well-designed RCTs examining the efficacy of mindfulness relative to control groups. These RCTs have shown that the intervention is effective in reducing depression and demonstrating improvements in well-being (Goldberg et al., 2021; Hofmann & Gómez, 2017; Strauss et al., 2014). Previous reviews have also shown that MBSIs positively affect well-being and depression among youth (Chi et al., 2018; Erbe & Lohrmann, 2015). Our findings also are inconsistent with previous meta-analyses with adults (Khoury et al., 2015) and youth (Dunning et al., 2019; McKeering and Hwang, 2019), which suggested that mindfulness practice improves well-being.

The next tier of evidence (B grade) supported the role of MBSIs in improving self-concept, social competence, self- and emotion regulation, coping, executive function, cognitive control, and mood, as well as reducing social bias and attentional problems. Our review accords with previous studies (Joss et al., 2019; Nejati et al., 2015; Quaglia et al., 2019) and a recent narrative review (Renshaw & Cook, 2017) of MBSIs, which strengthens the evidence that MBSIs improve these outcomes for youth (Barnes et al., 2003; Flook et al., 2010; Mendelson et al., 2010). With improved self-concept and social competence, students can pay attention without judgment to what is happening with themselves and with others (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015). This can allow them to become resilient and to confront the challenges they will face in classroom settings, such as exam stress, problems concentrating, and dealing with difficult peers (Keye & Pidgeon, 2013). As a result of mindful practice, students may be better able to increase overall self-care by making constructive changes in their personal and professional lives, allowing for a healthier relationship with themselves and with others (Napoli & Bonifas, 2011).

Strong (B grade) evidence also showed that MBSIs improved mindfulness, awareness of thoughts, feelings, emotions, and bodily sensations, being more present in life, concentration, and attention, as well as reduced mind-wandering, distractibility and impulsivity. Our findings on these outcomes are in line with increasing evidence on the benefits of mindfulness for adults (Norris et al., 2018; Rahl et al., 2017; Shapero et al., 2018) and youth (Dunning et al., 2019; Renshaw, 2020). Although there is strong (B grade) evidence showing improved attention and reduced mind-wandering, there is still insufficient evidence as to how much mindfulness practice is needed to benefit students’ attention regulation (Wimmer et al., 2020). Therefore, future studies should focus on the dosage—whether the length of intervention time, number of sessions, or total mindfulness practice time—needed for students to achieve improved attention regulation.

Strong (B grade) evidence also showed that MBSIs improved academic performance, specifically, report card grades, auditory-verbal memory, GPA, math, and social studies performance. Several studies examining MBSIs have been shown to improve academic performance with children (Lu et al., 2017; Thierry et al., 2016) although one review found that MBSIs did not improve academic achievement (Maynard et al., 2017). Given the mixed results, the methodological differences in the quality of reviews compared to studies should be considered before determining whether MBSIs improve academic performance with children. It is noteworthy that gender differences in response to mindfulness may also play an important role in youth academic performance. For example, a preliminary analysis indicated a greater increase in both mindfulness and self-compassion for females compared to males (Bluth et al., 2017). Likewise, in terms of academics, girls tend to achieve higher grades than boys (Duckworth & Seligman, 2006; Duckworth et al., 2015). Therefore, examining potential gender effects is especially important given the prevalence of gender differences in affective disturbances and treatment outcomes among youth (Kang et al., 2018). Future studies are needed to further explore these factors when looking at gender and academic performance to refine and enhance existing programs and to inform future development of MBSIs.

Nonetheless, a smaller group of studies suggested positive changes (B grade) in physiology, neurophysiology, and brain plasticity. MBSIs have been shown to influence physiological changes in adults, although relatively fewer studies examine this connection compared to other behavioral and mental health outcomes (Creswell et al., 2019). Given our knowledge of brain plasticity in early development, future research in this area with children is especially important (Black, 2015; Burke, 2010; Zoogman et al., 2015). Considering the potential neurophysiological processes of mindfulness, future studies should also explore the relationships among length and quality of mindfulness practice, developmental stages of students, and their mental health outcomes (Wielgosz et al., 2019). These factors may benefit MBIs in schools by improving memory and language skills (i.e., reading), which can increase academic success (Mundkur, 2005).

Overall, there were no systematic differences between positive vs. null/negative effect studies in terms of research design (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed), evaluation design (RCT, pre-post, single case/series, etc.), and per control group type (active, passive, none), suggesting overall consistency in terms of these factors in the body of literature to date on MBSIs. However, there were outcomes in need of higher quality evidence, including self-compassion, psychological and physiological stress, academic performance, and acceptability.

Limitations and Future Research

There are several areas of notable strengths when considering the literature on MBSIs used in schools. All studies reported on group-based interventions conducted in typical classrooms during normal school hours, suggesting the generalizability of the results to school-based practice. Another strength is that many studies in this review used components of MBSR, the mindfulness-based intervention with the most empirical support for its effectiveness (Kabat‐Zinn, 2003; Klingbeil, Fischer, et al., 2017; Klingbeil, Renshaw, et al., 2017; Kriakous et al., 2020). Finally, several studies included data on student educational, attentional, and behavioral outcomes, such as student achievement, ability to focus, and grades. However, additional studies and meta-analyses are needed to explore the evidence of the effectiveness of MBSIs on these educational outcomes, which may be relevant to educators and other school-based stakeholders.

Nevertheless, the literature exploring the effects of MBSIs with youth has several limitations. Many studies included in this review relied on small samples, with studies averaging around 35 participants. Future studies may benefit from larger sample sizes to power statistical analyses adequately and to aid in the generalizability of the findings. There also are significant limitations in how outcomes were measured. Most studies relied on questionnaire measures to assess for effects (particularly student self-report), which are limited by possible response bias and retrospective memory biases. Although some studies included used multiple methods (e.g., subjective self-reports, behavioral observations, and objective neurocognitive, and physiological testing), the majority relied on a single method. To address these limitations, we recommend future MBSI studies to collect data regarding the training quality of the instructors and the amount of meditation conducted during training, as well as to use substantially larger and more diverse samples of students to examine both the immediate and long-term impact of mindfulness training post-treatment.

A third limitation of studies included in this review was the lack of reporting of participant characteristics. For example, 40% of studies in this review did not provide details about participant race and ethnicity, which is important given the underrepresentation of racial and ethnic populations in rigorous trials of MBIs (Waldron et al., 2018). Very few studies included students receiving education supports, and only five studies specifically examined the impact of MBSIs on children with disabilities (see Online Resource 1 for more details). Given that most of these studies were conducted through whole class instruction, it is possible that existing mindfulness interventions are not well suited to the specific needs and reality of a classroom for children with disabilities. Attention to specific developmental child characteristics (e.g., cognitive ability, attention span) is therefore required when adapting MBSIs.

Few studies, all of lower quality, investigated the impact of MBSIs on problem behaviors such as aggression, disruptive behaviors, conduct behavior, and externalizing problems. More studies of higher quality are needed to better address these problem behaviors in schools since it has been positively associated with teacher burnout and self-efficacy (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000; Burke et al., 1996). This leads to poor student–teacher relationships, which could affect students’ learning and achievement (Herman et al., 2018). Although many studies examined the acceptability and feasibility of child adaptations to adult MBIs (Bluth et al., 2016; Broderick & Metz, 2009; Hiltz & Swords, 2021; Luiselli et al., 2017; Metz et al., 2013; Quach et al., 2017), future work on MBSIs should consider scalability and other factors known to impact the implementation of other school-based or youth-focused programs. This includes principal and district buy-in, individual attitudes towards the intervention, and organizational climate and culture, as well as implementation climate and leadership (Locke et al., 2016). To facilitate effective implementation and sustainment of MBSIs, studies should use a mixed-methods approach to assess both outcomes and acceptability, adopting methods such as teacher reports on student outcomes, review sessions, observations of training sessions, and student questionnaires and interviews (Zenner et al., 2014).

Finally, despite compelling theory and emerging evidence from adult samples (Gu et al., 2015), no studies examined the mechanisms or active ingredients of mindfulness to understand the key components of MBSIs for producing positive outcomes. These studies are essential to explore the various active ingredients in mindfulness-based interventions such as social support, relaxation, and cognitive-behavioral elements. Examining the central construct of mindfulness itself is also important to determine if the development of mindfulness is what leads to the positive changes that have been observed (Shapiro et al., 2006). This is important to advance knowledge on how to best develop, adapt, and implement MBSIs to optimize outcomes. Also, no studies examined the long-term impact of MBSIs after 1 year, which would be beneficial in learning about the lasting impact that MBSIs have on youth. Future studies should therefore examine both mediating mechanisms and the long-term impact of school-based mindfulness training post-treatment.

We should note several limitations of our review methodology as well. First, we did not include gray/unpublished literature, which may have resulted in missing some relevant studies. Indeed, there may have been a publication bias in the literature included, in that published studies are systematically different from results of unpublished studies due to either non-submission for publication or rejection at the review stage. Second, we did not evaluate specific mindfulness practices (e.g., sitting meditation, body scan, movement meditations) and program delivery aspects (e.g., level of teacher training). Given that mindfulness training is highly variable across studies, it is important for future research to examine these factors to determine which intervention best fits the needs of youth. We also did not examine program fidelity, which is important to moderate the relationship between the intervention and its outcomes as well as to prevent potentially false conclusions from being drawn about the intervention’s effectiveness. Third, our review did not analyze the age appropriateness and pedagogy used for MBSIs so future studies may benefit from examining these factors. We would also like to acknowledge that comparing public school versus private school as well as integrating socioeconomic status into the analysis would have added to higher quality studies. Given that our study did not incorporate this into our analysis, we recommend that future studies consider these factors when examining the quality of MBSIs. Furthermore, our “Results” section focused mainly on the outcomes of the MBSIs without reporting the differences in the effectiveness of MBSIs based on the other data that was extracted from individual studies (e.g., research or evaluation design, teacher training, educational level). Since our review examined the quality of outcome evidence by research design, as well as quantity and strength of evidence across studies, examining the differences in the effectiveness of MBSIs based on the mentioned constructs is beyond the scope of our study. The descriptive information we coded about the studies was intended to describe the characteristics of the population studies we reviewed rather than examining moderator and mediator analyses. As such, we suggest future studies to include moderator and mediator analyses when looking at the overall effectiveness of MBSIs and suggest considerations of these factors in further considerations of outcome quality. Finally, there are limitations to using a systematic review methodology, which could have resulted in the variability of our findings. Various design factors such as the educational level of students, type of intervention, and type of delivery may have impacted the lack of effectiveness observed in this present review. We recommend future studies to conduct a meta-analysis using high-quality evidence, especially for the outcomes with mixed results.

This study reviews the studies of MBSIs for youth using a robust system for grading recommendations that considers the methodological rigor of studies to determine effectiveness recommendations of MBSIs for producing certain outcomes. Strong evidence (B grade) indicates that MBSIs improve self-compassion, social relationships, mental health, self-regulation and emotionality, mindful awareness, attentional focus, physiological stress, and academic performance. The strongest evidence (A grade) indicated that MBSIs produce improvements in resilience and anxiety across youth. In addition, the strongest evidence suggests no changes in decreasing depression symptoms and increasing well-being across youth receiving MBSIs. Given the difficulties that children and adolescents face in an increasingly demanding world, this review demonstrates the promise of incorporating mindfulness interventions to youth in a school setting. Despite the benefits that MBSIs may have with youth, this area of research is still maturing, with many studies incorporating pre-post design or otherwise less rigorous evaluation methods. Therefore, we urge researchers interested in MBSIs to study their effectiveness using more rigorous designs (e.g., RCTs with active control groups, multi-method outcome assessment, and follow-up evaluation), to minimize bias and promote higher quality—not just increased quantity—evidence that can be relied upon to guide school-based practice.

Change history

20 November 2022

The ESM is missing and needs to be added.

References

* = Study included in the systematic review.

*Atkinson, M. J., & Wade, T. D. (2015). Mindfulness-based prevention for eating disorders: A school-based cluster randomized controlled study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(7), 1024–1037. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22416

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg015

*Bakosh, L. S., Snow, R. M., Tobias, J. M., Houlihan, J. L., & Barbosa-Leiker, C. (2016). Maximizing mindful learning: Mindful awareness intervention improves elementary school students’ quarterly grades. Mindfulness, 7(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0387-6

*Bakosh, L. S., Tobias Mortlock, J. M., Querstret, D., & Morison, L. (2018). Audio-guided mindfulness training in schools and its effect on academic attainment: Contributing to theory and practice. Learning and Instruction, 58, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.04.012

*Bannirchelvam, B., Bell, K. L., & Costello, S. (2017). A qualitative exploration of primary school students’ experience and utilisation of mindfulness. Contemporary School Psychology, 21(4), 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0141-2

Barnes, V. A., Bauza, L. B., & Treiber, F. A. (2003). Impact of stress reduction on negative school behavior in adolescents. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/2F1477-7525-1-10

*Bauer, C. C. C., Caballero, C., Scherer, E., West, M. R., Mrazek, M. D., Phillips, D. T., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2019). Mindfulness training reduces stress and amygdala reactivity to fearful faces in middle-school children. Behavioral Neuroscience, 133(6), 569–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/bne0000337

*Beauchemin, J., Hutchins, T. L., & Patterson, F. (2008). Mindfulness meditation may lessen anxiety, promote social skills, and improve academic performance among adolescents with learning disabilities. Complementary Health Practice Review, 13(1), 34-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533210107311624

*Bei, B., Byrne, M. L., Ivens, C., Waloszek, J., Woods, M. J., Dudgeon, P., Murray, G., Nicholas, C. L., Trinder, J., & Allen, N. B. (2013). Pilot study of a mindfulness-based, multi-component, in-school group sleep intervention in adolescent girls. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 7(2), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00382.x

Bender, S. L., Roth, R., Zielenski, A., Longo, Z., & Chermak, A. (2018). Prevalence of mindfulness literature and intervention in school psychology journals from 2006 to 2016. Psychology in the Schools, 55(6), 680–692. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22132

*Bennett, K., & Dorjee, D. (2016). The impact of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction course (MBSR) on well-being and academic attainment of sixth-form students. Mindfulness, 7(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0430-7

*Berger, R., Brenick, A., & Tarrasch, R. (2018). Reducing Israeli-Jewish pupils’ outgroup prejudice with a mindfulness and compassion-based social-emotional program. Mindfulness, 9(6), 1768–1779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0919-y

*Bernay, R., Graham, E., Devcich, D. A., Rix, G., & Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2016). Pause, breathe, smile: A mixed-methods study of student well-being following participation in an eight-week, locally developed mindfulness program in three New Zealand schools. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 9(2), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2016.1154474

Biegel, G. M., Brown, K. W., Shapiro, S. L., & Schubert, C. M. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 855–866. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016241

*Black, D. S., & Fernando, R. (2014). Mindfulness training and classroom behavior among lower-income and ethnic minority elementary school children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(7), 1242–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9784-4

Black, D. S. (2015). Mindfulness training for children and adolescents. Handbook of Mindfulness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 283, 246–263.

*Bluth, K., Campo, R. A., Pruteanu-Malinici, S., Reams, A., Mullarkey, M., & Broderick, P. C. (2016). A school-based mindfulness pilot study for ethnically diverse at-risk adolescents. Mindfulness, 7(1), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0376-1

Bluth, K., Roberson, P. N. E., & Girdler, S. S. (2017). Adolescent sex differences in response to a mindfulness intervention: A call for research. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(7), 1900–1914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0696-6

Bootzin, R. R., & Stevens, S. J. (2005). Adolescents, substance abuse, and the treatment of insomnia and daytime sleepiness. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(5), 629–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.04.007

Borquist-Conlon, D. S., Maynard, B. R., Brendel, K. E., & Jarina, A. S. (2019). Mindfulness-based interventions for youth with anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice, 29, 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731516684961

Bostic, J. Q., Nevarez, M. D., Potter, M. P., Prince, J. B., Benningfield, M. M., & Aguirre, B. A. (2015). Being present at school: Implementing mindfulness in schools. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(2), 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.11.010

*Bradley, C., Cordaro, D. T., Zhu, F., Vildostegui, M., Han, R. J., Brackett, M., & Jones, J. (2018). Supporting improvements in classroom climate for students and teachers with the four pillars of wellbeing curriculum. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(3), 245. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000162

Britton, W. B., Haynes, P. L., Fridel, K. W., & Bootzin, R. R. (2010). Polysomnographic and subjective profiles of sleep continuity before and after mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in partially remitted depression. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(6), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0b013e3181dc1bad

*Britton, W. B., Lepp, N. E., Niles, H. F., Rocha, T., Fisher, N., & Gold, J. (2014). A randomized controlled pilot trial of classroom-based mindfulness meditation compared to an active control condition in 6th grade children. Journal of School Psychology, 52(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2014.03.002

*Broderick, P. C., & Metz, S. (2009). Learning to BREATHE: A pilot trial of a mindfulness curriculum for adolescents. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 2(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2009.9715696

Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2000). A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(2), 239–253.

Burckhardt, R., Manicavasagar, V., Batterham, P. J., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & Shand, F. (2017). Acceptance and commitment therapy universal prevention program for adolescents: A feasibility study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 11(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0164-5

Burke, C. A. (2010). Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: A preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9282-x

Burke, R. J., Greenglass, E. R., & Schwarzer, R. (1996). Predicting teacher burnout over time: Effects of work stress, social support, and self-doubts on burnout and its consequences. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 9(3), 261–275.

Caldwell, D. M., Davies, S. R., Hetrick, S. E., Palmer, J. C., Caro, P., López-López, J. A., Gunnell, D., Kidger, J., Thomas, J., French, C., Stockings, E., Campbell, R., & Welton, N. J. (2019). School-based interventions to prevent anxiety and depression in children and young people: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(12), 1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30403-1

Carsley, D., Khoury, B., & Heath, N. L. (2018). Effectiveness of mindfulness interventions for mental health in schools: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 9(3), 693–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0839-2

Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005

Chi, X., Bo, A., Liu, T., Zhang, P., & Chi, I. (2018). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1034. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01034

Coholic, D., Dano, K., Sindori, S., & Eys, M. (2019). Group work in mindfulness-based interventions with youth: A scoping review. Social Work with Groups, 42(4), 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2019.1571764

*Costello, E., & Lawler, M. (2014).An exploratory study of the effects of mindfulness on perceived levels of stress among school-children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. The International Journal of Emotional Education, 6(2), 19

*Crescentini, C., Capurso, V., Furlan, S., & Fabbro, F. (2016). Mindfulness-oriented meditation for primary school children: Effects on attention and psychological well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00805

Creswell, J. D., Lindsay, E. K., Villalba, D. K., & Chin, B. (2019). Mindfulness training and physical health: Mechanisms and outcomes. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81(3), 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000675

*Davenport, C., & Pagnini, F. (2016). Mindful learning: A case study of Langerian mindfulness in schools. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01372

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006

*der Gucht, K. V., Takano, K., Kuppens, P., & Raes, F. (2017). Potential moderators of the effects of a school-based mindfulness program on symptoms of depression in adolescents. Mindfulness, 8(3), 797–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0658-x

*Dove, C., & Costello, S. (2017). Supporting emotional well-being in schools: A pilot study into the efficacy of a mindfulness-based group intervention on anxious and depressive symptoms in children.Advances in Mental Health, 15(2), 172–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2016.1275717

Duckworth, A. L., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Self-discipline gives girls the edge: Gender in self-discipline, grades, and achievement test scores. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 30. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.198

Duckworth, A. L., Shulman, E. P., Mastronarde, A. J., Patrick, S. D., Zhang, J., & Druckman, J. (2015). Will not want: Self-control rather than motivation explains the female advantage in report card grades. Learning and Individual Differences, 39, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.02.006

Dunning, D. L., Griffiths, K., Kuyken, W., Crane, C., Foulkes, L., Parker, J., & Dalgleish, T. (2019). The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents–A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(3), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12980

*Emerson, L.-M., Rowse, G., & Sills, J. (2017).Developing a mindfulness-based program for infant schools: Feasibility, acceptability, and initial effects. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 31(4), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2017.1343211

Erbe, R., & Lohrmann, D. (2015). Mindfulness meditation for adolescent stress and well-being: A systematic review of the literature with implications for school health programs. Health Educator, 47(2), 12–19.

*Eva, A. L., & Thayer, N. M. (2017). Learning to BREATHE: A pilot study of a mindfulness-based intervention to support marginalized youth. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 22(4), 580–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587217696928

*Felver, J. C., Doerner, E., Jones, J., Kaye, N. C., & Merrell, K. W. (2013). Mindfulness in school psychology: Applications for intervention and professional practice. Psychology in the Schools, 50(6), 531–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21695

Felver, J. C., Celis-de Hoyos, C. E., Tezanos, K., & Singh, N. N. (2016). A systematic review of mindfulness-based interventions for youth in school settings. Mindfulness, 7(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0389-4

Felver, J. C., Frank, J. L., & McEachern, A. D. (2014). Effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of the soles of the feet mindfulness-based intervention with elementary school students. Mindfulness, 5(5), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0238-2

Fisher, R. (2006). Still thinking: The case for meditation with children. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 1(2), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2006.06.004

Fjorback, L. O., Arendt, M., Ørnbøl, E., Fink, P., & Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy – A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(2), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x

*Flook, L., Goldberg, S. B., Pinger, L., & Davidson, R. J. (2015). Promoting prosocial behavior and self-regulatory skills in preschool children through a mindfulness-based kindness curriculum. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038256

Flook, L., Smalley, S. L., Kitil, M. J., Galla, B. M., Kaiser-Greenland, S., Locke, J., Ishijima, E., & Kasari, C. (2010). Effects of mindful awareness practices on executive functions in elementary school children. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26(1), 70–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377900903379125

Forkmann, T., Wichers, M., Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., van Os, J., Mainz, V., & Collip, D. (2014). Effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on self-reported suicidal ideation: Results from a randomised controlled trial in patients with residual depressive symptoms. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(8), 1883–1890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.08.043

*Franco, C., Amutio, A., López-González, L., Oriol, X., & Martínez-Taboada, C. (2016).Effect of a mindfulness training program on the impulsivity and aggression levels of adolescents with behavioral problems in the classroom. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01385

*Fung, J., Guo, S., Jin, J., Bear, L., & Lau, A. (2016). A pilot randomized trial evaluating a school-based mindfulness intervention for ethnic minority youth. Mindfulness, 7(4), 819–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0519-7

Gawrysiak, M. J., Grassetti, S. N., Greeson, J. M., Shorey, R. C., Pohlig, R., & Baime, M. J. (2018). The many facets of mindfulness and the prediction of change following Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 523–535.

Goldberg, S. B., Riordan, K. M., Sun, S., & Davidson, R. J. (2021). The empirical status of mindfulness-based interventions: A systematic review of 44 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10.1177%2F1745691620968771

*Gouda, S., Luong, M. T., Schmidt, S., & Bauer, J. (2016). Students and teachers benefit from mindfulness-based stress reduction in a school-embedded pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00590

*Gould, L. F., Dariotis, J. K., Mendelson, T., & Greenberg, M. T. (2012). A school‐based mindfulness intervention for urban youth: Exploring moderators of intervention effects. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(8), 968-982. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21505

Greenberg, M. T., & Harris, A. R. (2012). Nurturing mindfulness in children and youth: Current state of research. Child Development Perspectives, 6(2), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00215.x

Greeson, J. M. (2009). Mindfulness research update: 2008. Complementary Health Practice Review, 14(1), 10–18.

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43.

Guendelman, S., Medeiros, S., & Rampes, H. (2017). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: Insights from neurobiological, psychological, and clinical studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00220

Harbour, R., & Miller, J. (2001). A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 323(7308), 334–336.

Hayes, A. M., & Feldman, G. (2004). Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph080

Herman, K. C., Hickmon-Rosa, J. E., & Reinke, W. M. (2018). Empirically derived profiles of teacher stress, burnout, self-efficacy, and coping and associated student outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(2), 90–100.

Hill, C. L. M., & Updegraff, J. A. (2012). Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion, 12(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026355

Hilt, L. M., & Swords, C. M. (2021). Acceptability and preliminary effects of a mindfulness mobile application for ruminative adolescents. Behavior Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2021.03.004

Hofmann, S. G., & Gómez, A. F. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 40(4), 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.008

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018555

Hoge, E. A., Bui, E., Marques, L., Metcalf, C. A., Morris, L. K., Robinaugh, D. J., Worthington, J. J., Pollack, M. H., & Simon, N. M. (2013). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: Effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(8), 786–792. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12m08083

Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671

*Idler, A. M., Mercer, S. H., Starosta, L., & Bartfai, J. M. (2017). Effects of a mindful breathing exercise during reading fluency intervention for students with attentional difficulties. Contemporary School Psychology, 21(4), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0132-3

Irving, J. A., Dobkin, P. L., & Park, J. (2009). Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: A review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 15(2), 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.01.002

Ivanovski, B., & Malhi, G. S. (2007). The psychological and neurophysiological concomitants of mindfulness forms of meditation. Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 19(2), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-5215.2007.00175.x

*Janz, P., Dawe, S., & Wyllie, M. (2019). Mindfulness-based program embedded within the existing curriculum improves executive functioning and behavior in young children: A waitlist controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02052

*Johnson, C., Burke, C., Brinkman, S., & Wade, T. (2016). Effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness program for transdiagnostic prevention in young adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 81, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.03.002

*Johnson, C., Burke, C., Brinkman, S., & Wade, T. (2017). A randomized controlled evaluation of a secondary school mindfulness program for early adolescents: Do we have the recipe right yet? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 99, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.09.001

Joss, D., Khan, A., Lazar, S. W., & Teicher, M. H. (2019).Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on self-compassion and psychological health among young adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02373

*Juliano, A. C., Alexander, A. O., DeLuca, J., & Genova, H. (2020). Feasibility of a school-based mindfulness program for improving inhibitory skills in children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 101, 103641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103641

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Kallapiran, K., Koo, S., Kirubakaran, R., & Hancock, K. (2015). Review: Effectiveness of mindfulness in improving mental health symptoms of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 20(4), 182–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12113

*Kang, Y., Rahrig, H., Eichel, K., Niles, H. F., Rocha, T., Lepp, N. E., Gold, J., & Britton, W. B. (2018). Gender differences in response to a school-based mindfulness training intervention for early adolescents. Journal of School Psychology, 68, 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.03.004

*Kasson, E. M., & Wilson, A. N. (2016). Preliminary evidence on the efficacy of mindfulness combined with traditional classroom management strategies. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10(3), 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0160-x

*Keller, J., Ruthruff, E., Keller, P., Hoy, R., Gaspelin, N., & Bertolini, K. (2017). “Your brain becomes a rainbow”: Perceptions and traits of 4th-graders in a school-based mindfulness intervention. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 31(4), 508–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2017.1343212

Kemeny, M. E., Foltz, C., Cavanagh, J. F., Cullen, M., Giese-Davis, J., Jennings, P., Rosenberg, E. L., Gillath, O., Shaver, P. R., Wallace, B. A., & Ekman, P. (2012). Contemplative/emotion training reduces negative emotional behavior and promotes prosocial responses. Emotion, 12(2), 338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026118

Keye, M. D., & Pidgeon, A. M. (2013). Investigation of the relationship between resilience, mindfulness, and academic self-efficacy. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 1(6), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2013.16001

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., Chapleau, M. A., Paquin, K., & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009

*Kielty, M., Gilligan, T., Staton, R., & Curtis, N. (2017). Cultivating mindfulness with third grade students via classroom-based interventions. Contemporary School Psychology, 21(4), 317–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0149-7

*Klatt, M., Harpster, K., Browne, E., White, S., & Case-Smith, J. (2013). Feasibility and preliminary outcomes for Move-Into-Learning: An arts-based mindfulness classroom intervention. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(3), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.779011

Klatt, M., Steinberg, B., & Duchemin, A.-M. (2015). Mindfulness in Motion (MIM): An onsite mindfulness based intervention (MBI) for chronically high stress work environments to increase resiliency and work engagement. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 101, e52359. https://doi.org/10.3791/52359

Klingbeil, D. A., Fischer, A. J., Renshaw, T. L., Bloomfield, B. S., Polakoff, B., Willenbrink, J. B., Copek, R. A., & Chan, K. T. (2017a). Effects of mindfulness-based interventions on disruptive behavior: A meta-analysis of single-case research. Psychology in the Schools, 54(1), 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21982

Klingbeil, D. A., Renshaw, T. L., Willenbrink, J. B., Copek, R. A., Chan, K. T., Haddock, A., Yassine, J., & Clifton, J. (2017b). Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: A comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 77–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.006

Kriakous, S. A., Elliott, K. A., Lamers, C., & Owen, R. (2020). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the psychological functioning of healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Mindfulness. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01500-9

*Kurth, L., Engelniederhammer, A., Sasse, H., & Papastefanou, G. (2020). Effects of a short mindful-breathing intervention on the psychophysiological stress reactions of German elementary school children. School Psychology International, 41(3), 218–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034320903480

Kuyken, W., Weare, K., Ukoumunne, O. C., Vicary, R., Motton, N., Burnett, R., Cullen, C., Hennelly, S., & Huppert, F. (2013). Effectiveness of the mindfulness in schools programme: Non-randomised controlled feasibility study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(2), 126–131. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.126649

*Lagor, A. F., Williams, D. J., Lerner, J. B., & McClure, K. S. (20130617). Lessons learned from a mindfulness-based intervention with chronically ill youth. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 1(2), 146. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000015

*Lam, K. (2016). School-based cognitive mindfulness intervention for internalizing problems: Pilot study with Hong Kong elementary students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(11), 3293–3308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0483-9

Langer, Á. I., Ulloa, V. G., Cangas, A. J., Rojas, G., & Krause, M. (2015). Mindfulness-based interventions in secondary education: A qualitative systematic review. Estudios De Psicología, 36(3), 533–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/02109395.2015.1078553

*Lassander, M., Hintsanen, M., Suominen, S., Mullola, S., Fagerlund, Å., Vahlberg, T., & Volanen, S.-M. (2020). The effects of school-based mindfulness intervention on executive functioning in a cluster randomized controlled trial. Developmental Neuropsychology, 45(7/8), 469–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2020.1856109

*Le, T. N., & Gobert, J. M. (2015). Translating and implementing a mindfulness-based youth suicide prevention intervention in a Native American community. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9809-z

*Le, T. N., & Trieu, D. T. (2016). Feasibility of a mindfulness-based intervention to address youth issues in Vietnam. Health Promotion International, 31(2), 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau101