Abstract

Objectives

To examine whether eating status and dietary variety were associated with functional disability during a 5-year follow-up analysis of older adults living in a Japanese metropolitan area.

Design

A 5-year follow-up study.

Setting

Ota City, Tokyo, Japan.

Participants

A total of 10,308 community-dwelling non-disabled adults aged 65–84 years.

Measurements

Eating status was assessed using a self-reported questionnaire. Dietary variety was assessed using the dietary variety score (DVS). Based on the responses, participants were classified according to eating alone or together and DVS categories (low: 0–3; high: 4–10). Functional disability incidence was prospectively identified using the long-term care insurance system’s nationally unified database. Multilevel survival analyses calculated the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for incident functional disability.

Results

During a 5-year follow-up, 1,991 (19.3%) individuals had functional disabilities. Eating status or DVS were not independently associated with incident functional disability. However, interaction terms between eating status and DVS were associated with functional disability; HR (95% CI) for eating together and low DVS was 1.00 (0.90–1.11), eating alone and high DVS was 0.95 (0.77–1.17), and eating alone and low DVS was 1.20 (1.02–1.42), compared to those with eating together and high DVS.

Conclusion

Older adults should avoid eating alone or increase dietary variety to prevent functional disability. This can be ensured by providing an environment of eating together or food provision services for eating a variety of foods in the community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Japan is one of the world’s most rapidly aging countries. It is estimated that 35% of Japan’s population will comprise individuals aged 65 years and above by 2040, which makes it important to control the increase in the number of people requiring long-term care and to extend healthy life expectancy (1). The aging of society leads to a rise in the number of people living alone (1). Especially in Japanese metropolitan areas, it is estimated that about 30% of older people will live alone, and about 45% of elderly households will comprise single members by 2040. Living alone has been reported to be associated with the risk of malnutrition (2) and can lead to increased long-term care status and mortality (3).

These demographic trends are likely to increase the frequency of eating alone among older adults (4). Eating alone has been identified as one of the risk factors for malnutrition associated with eating behavior (5), reducing dietary variety (6, 7), nutrition intake (8), and appetite (9). Several studies have indicated that eating alone is associated with depression (6, 10, 11) and mortality among older men living with others (12). Reduced social networks and social support after losing a spouse or peers and friends among older adults can lead them to eat alone. However, maintaining functional social support networks in old age is associated with healthy dietary behaviors (5). In other words, preventing social isolation and eating together are important for maintaining healthy eating behaviors and health status among older adults.

Over the last few years, several dietary guidelines have recommended consuming a variety of foods (13, 14) customized to fit unique local dietary cultures (e.g., Healthy Eating Index, Mediterranean diet, Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension, and Japanese Diet Index). Many of these dietary patterns have been reported to be beneficial for middle-aged and older adults (15–18). In Japan, a simple indicator used to assess dietary variety is the dietary variety score (DVS) (19). A higher DVS has been positively associated with physical function (20, 21) and reduced depression (22).

Many studies have examined the individual associations between eating status and dietary variety with health status and physical function, respectively. Since eating alone has been shown to reduce dietary variety (6, 7), the association between dietary variety and health outcomes may differ depending on eating status. However, no studies have yet investigated the interactive association between eating status and dietary variety in cases of functional disability among older adults. To bridge this gap in the literature, this study examines the combined impacts of eating alone and dietary variety on incident functional disability among older adults living in a metropolitan area of Japan.

Methods

Study population

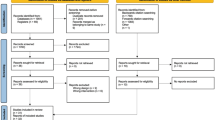

Study data were obtained from a community-wide intervention study on preventing frailty, launched in 2016 in Ota City, Tokyo, Japan (23, 24). A total of 15,500 residents who did not have long-term care insurance (LTCI) certification (25), aged 65–84 years, stratified by sex and age group (65–74 and 75–84 years), were selected using random sampling strategies in all 18 districts of the city (23). In July 2016, 15,500 self-administered questionnaires were distributed, out of which 11,925 were returned (response rate: 76.9%). Finally, 10,308 questionnaires (5,049 men and 5,259 women) that had no missing eating status, dietary variety, and incident functional disability items and did not match the exclusion criteria were included in the present analysis (Figure 1).

The study protocol was developed in accordance with the guidelines proposed in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology. All the participants gave their informed consent before participation.

Measurements

Eating status

The eating status of participants was assessed using the question: “Who do you usually have meals with?” Multiple response choices were as follows: “only yourself,” “spouse,” “children,” “children’s spouse,” “parents,” “spouse’s parents,” “grandchildren/great-grandchildren,” “friends,” and “others” (10). Responses of eating alone (“only yourself”) or eating together (anything but “only yourself”) were focused on in this study.

Dietary variety

Dietary variety was assessed using the DVS (19). The DVS comprises 10 food groups (meat, fish/shellfish, eggs, milk, soybean products, green/yellow vegetables, potatoes, fruit, seaweed, and fats/oils). Respondents were asked to choose from the following four options: “almost daily,” “once every two days,” “once or twice a week,” and “almost never.” For the DVS, 1 point was given only when a respondent chose “almost daily,” and 0 was given for all other items, and the total score was computed. The total score ranged from 0 to 10; higher scores indicated greater dietary variety. Previous studies have reported that DVS ≤3 is associated with a higher risk of decline in muscle mass and physical function and a higher risk of depression (21, 22). In this study, 0–3 points were considered low, and 4–10 points were considered high.

Functional disability

Functional disability was defined by the LTCI certification, which employs a nationally standardized, multistep assessment of elderly health (25). All citizens aged 40 years and above in Japan pay premiums and are covered by the system, and all citizens aged 65 years and above are eligible for formal caregiving services (25). To receive caregiving services through the LTCI system, an individual must be certified according to the national uniform standards (25). The Municipal Certification Committee of Needed Long-Term Care (comprising physicians, nurses, and health and social service experts) decides whether an older adult should be certified as requiring long-term care and classifies care needs under one of seven levels (Support Levels 1–2; Care Levels 1–5). The LTCI certification levels are defined from Support Level 1 (i.e., “limited in instrumental activities of daily living [ADL] but independent in basic ADL”) to Care Level 5 (i.e., “requiring care in all ADL tasks”). Functional disability was defined as the onset of long-term care needs at Support Level 1 or above, using the date of LTCI application as the date of disability incident. Moreover, we classified the onset of Support Levels 1–2 or Care Levels 1–5 to examine low disability levels and incident severe disability. For the purpose of this study, July 1, 2021, was considered the endpoint.

Covariates

The covariates in this study were age, sex, living situation (living with others or alone), education level (presence or absence of ≥college/vocational), equivalent income (presence or absence of ≥2.5 million yen/year), body mass index (BMI; thinness: <21.5 kg/m2, obesity: ≥25 kg/m2), heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, cancer, bone/joint disease, smoking status (current, never, or former), exercise habits, social isolation, and depressive mood. Equivalent income was calculated by dividing household income by the square root of the number of household members (26). BMI was defined as self-rated body weight (kg) divided by self-rated height squared (m2), which was divided into thinness (<21.5) and obesity (≥25.0) (27). Exercise habits were defined as more frequently than once per week. Social isolation was defined as face-to-face or non-face-to-face contact with individuals outside the household less frequently than once per week (28–30). Depressive mood was defined as a score of ≥2 on the 5-item Geriatric Depression Scale. (31, 32).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata 17.0 (StataCorp, TX, USA). An a value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance. DVS and age were analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test to confirm the data’s normality. To examine the continuous variables associated with eating alone and DVS, one-way ANOVA was used. Similarly, chi-square test was conducted for categorical variables. The impact of the two individual factors — eating status and DVS — on incident disability risk was assessed. As the current data had a multilevel structure comprising individuals (at Level 1) nested within 18 districts (at Level 2), multilevel survival analyses with fixed slopes and random intercept models were conducted—calculating the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for incident disability, Support Levels, or Care Levels. Eating status and DVS were simultaneously included as fixed factors, and the district was considered as a random factor. Two analytical models were constructed. Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex, and Model 2 included all covariates. Multicollinearity was checked by using the tolerance and variance inflation factors (VIF).

The combination categories of the fixed factors, eating status and DVS (reference as eating together and high DVS), were analyzed. We conducted secondary and stratified analyses. First, regarding the possible influence of reverse causation, sensitivity analyses were performed using the same statistical approach, after excluding individuals who developed a functional disability by the second year of follow-up. Second, regarding the possible influence of a potential dose-response relationship with DVS, sensitivity analyses were performed using the same statistical approach, using DVS as a continuous variable. Third, since living situation is thought to influence eating status, stratified analyses were performed using the same statistical approach by living situation.

Participants with missing information regarding their disability, eating status, and DVS were excluded from the analysis. The missing covariates were assigned to the “missing” category and included in the analysis to reduce selection bias.

Results

During a median follow-up of 5.1 (interquartile range: 5.1–5.1) years, a total of 1,991 (19.3%; 975 men and 1016 women) participants presented with disabilities, with rates of 43.4 per 1000 person-years, and 787 (39.5%; 394 men and 393 women) presented with a disability during the first two years. When we categorized the low disability levels and incident severe disability, 816 participants were certified as Support Levels 1–2 and 1,410 participants were certified as Care Levels 1–5 during the follow-up period. Additionally, 319 (39.1%) and 586 (41.6%) were certified during the first two years, respectively.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population based on eating status and DVS. There were significant differences between groups in terms of age, sex, living situation, marital status, education level, equivalent income, BMI, the prevalence of heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, bone/joint disease, smoking status, exercise habits, social isolation, and depressive mood.

Table 2 indicates the independent associations of eating status and DVS with incident disability. Eating alone (HR, 1.11; 95%CI, 0.97–1.27) and low DVS (HR, 1.04; 95%CI, 0.95–1.15) were not significantly independently associated with incident disability. Similarly, eating status and DVS were not significantly independently associated with the certification of Support Levels or Care Levels.

Table 3 indicates the combined associations of eating status and DVS with incident disability. Compared with people eating together and high DVS, disability risk was significantly higher among participants eating alone and low DVS (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.02–1.42), but not in eating together and low DVS (HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.90–1.11) or eating alone and high DVS (HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.77–1.17). Similar results were found at the Support Levels and Care Levels.

Supplementary Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4 indicate the results of the sensitivity and stratified analyses. Although sensitivity and stratified analyses showed that the results did not substantially differ from those of primary analyses, the significance of the effect of increased risk of Care Levels by DVS disappeared in additional analysis using DVS as a continuous variable (Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, eating alone attenuated the effects of the reduced risk of functional disability by high DVS for those who were living together (Supplementary Table S4).

Discussion

This study examined whether eating status and dietary variety were associated with functional disability during 5-year follow-up analysis of older adults living in a Japanese metropolitan area. The results indicated that eating status and dietary variety were not independently associated with functional disability. However, there was an interaction between eating status and dietary variety showing that eating alone and low DVS increased the risk of functional disability when compared to eating together and high DVS. Therefore, it is pertinent for the elderly to either avoid eating alone or eat a variety of foods to reduce the risk of functional disability.

The interaction term between eating status and dietary variety was statistically significant, which suggests that eating together or eating a variety of foods may be important in reducing the risk of functional disability. Compared with eating together and high DVS, eating alone and low DVS increased the risk of functional disability, but satisfying either can reduce the increased risk. It is a fact that living alone is an important factor responsible for eating alone among older adults. Eating alone could manifest because of an imbalance in lifestyle rhythms, such as mealtimes between family members and poor family relationships (33). The present study showed a trend that increased the risk associated with high DVS combined with eating alone among those living together, compared to those with both high DVS and eating together. Hence, promoting and providing opportunities within the family and community to eat together is necessary. A previous study showed that eating alone was associated with poor food shopping assistance and/or not receiving any food from neighbors or relatives (34). Social support is important not only for eating alone but also for dietary variety, as poor social support and economic disadvantage, as well as frailty, are associated with reduced dietary variety (35). However, these services and community measures are not widespread or sufficiently advanced in the community. Enhancing these services would be important to reduce the risk of functional disability.

However, the independent association between eating status and disability identified in this study is not consistent with that in previous studies, which have shown that older men living with others and eating alone have an increased risk of mortality (12), and eating alone has been associated with nutritional risk (5), poor appetite (9), and depression (6, 10, 11). In this study, the relationship between eating alone and functional disability was nullified by adjusting for physical function, lifestyle, and depression, thus suggesting that these variables may mediate the association between eating alone and disability.

Similarly, dietary variety was not independently associated with disability, which is also not consistent with the findings of previous studies. Several studies have indicated that dietary variety reduces all-cause and cancer mortality (36, 37), and the Japanese dietary pattern is associated with a lower risk of disability (17, 18). While these studies have assessed dietary variety and Japanese dietary pattern using detailed dietary records or food frequency questionnaires, the DVS was calculated based on the weekly frequency of intake from 10 food groups (19). Therefore, it is likely that no association was found due to the underestimation of the effect of dietary intake. Moreover, the median (interquartile range) of the DVS in this study was 3 (1–5), and about 60% of the participants were classified in the category of low DVS. Although DVS cut-off scores in this study were set based on previous studies (21, 22), it may be necessary to set cut-off scores according to the specific study population or the methods of data acquisition because DVS from self-administered mail survey data (23, 38) is typically reported as lower than those obtained from health check-up data. (19, 21, 22)

Limitations & Strength

Although this study reveals important findings, it has several limitations. First, the self-administered questionnaire used in this study may have involved recall bias. DVS from self-administered questionnaires may be underestimated compared to face-to-face interview surveys (19, 21–23, 38), and this underestimation could have attenuated its association with the outcome variables. Second, the presence of confounding variables such as cognitive status and meal delivery services that were not measured cannot be completely ruled out and could overestimate the results. Nevertheless, since this survey excluded residents who have LTCI certification, it is thought that the impact on the quality of the answers would be minimized. Third, the DVS was calculated based on the intake frequency of 10 food groups, which is not comparable to actual dietary intake. However, previous studies indicate that a higher DVS was associated with a higher intake of protein and micronutrients (39), and since protein intake increased as DVS increased with an intervention program (40). Therefore, the DVS might indicate a limited understanding of dietary intake. Fourth, an older adult in Japan must contact the municipal government to officially certify his or her care needs (25). Some disabled individuals might have failed to report themselves, resulting in the underestimation of disability incidence (detection bias). The associations between eating status and DVS with an incident disability may also have been underestimated in this study because of a decrease in new LTCI applications during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic (41). Finally, it should be noted that this study employed data sources from a community-wide intervention study. The DVS in the intervention subgroup improved at the population level (24). This study only assessed the baseline eating habits of participants and was unable to record subsequent changes in eating habits during the follow-up. If eating habits improved during follow-up, the relationship between eating habits and functional disability risk, as identified in this study, may have been underestimated.

Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study among Japanese older adults wherein eating together or increased dietary variety was found to reduce the risk of functional disability during a 5-year follow-up period.

Conclusion

Although eating status and dietary variety were not independently associated with functional disability, interactions between eating status and dietary variety reduced the risk of functional disability. Therefore, it is important for older adults to avoid eating alone or to eat a variety of foods. This can be ensured by providing an environment of eating together or food provision services for eating a variety of foods in the community.

References

Japan Cabinet Office (2021) Annual Report on the Ageing Society. https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/english/annualreport/2021/pdf/2021.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2022

Besora-Moreno M, Llaurado E, Tarro L, Sola R. Social and economic factors and malnutrition or the risk of malnutrition in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients 2020; 12:737. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030737

Tabue Teguo M, Simo-Tabue N, Stoykova R, Meillon C, Cogne M, Amieva H, Dartigues JF. Feelings of loneliness and living alone as predictors of mortality in the elderly: The PAQUID Study. Psychosom Med 2016; 78:904–909. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000386

Japan Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (2021) The Fourth Basic Plan for the Promotion of Shokuiku. https://www.maff.go.Jp/e/policies/tech_res/attach/pdf/shokuiku-18.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2022

Tani Y, Kondo N, Takagi D, Saito M, Hikichi H, Ojima T, Kondo K. Combined effects of eating alone and living alone on unhealthy dietary behaviors, obesity and underweight in older Japanese adults: Results of the JAGES. Appetite 2015; 95:1–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.06.005

Kimura Y, Wada T, Okumiya K, Ishimoto Y, Fukutomi E, Kasahara Y, Chen W, Sakamoto R, Fujisawa M, Otsuka K, Matsubayashi K: Eating alone among community-dwelling Japanese elderly: association with depression and food diversity. J Nutr Health Aging 2012, 16:728–731. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-012-0067-3

Tanaka I, Kitamura A, Seino S, Nishi M, Tomine Y, Taniguchi Y, Yokoyama Y, Narita M, Shinkai S. Relationship between eating alone and dietary variety among urban older Japanese adults. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2018; 65:744–754 (in Japanese). doi: https://doi.org/10.11236/jph.65.12_744

Chae W, Ju YJ, Shin J, Jang SI, Park EC. Association between eating behaviour and diet quality: eating alone vs. eating with others. Nutr J 2018; 17:117. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-018-0424-0

Mikami Y, Motokawa K, Shirobe M, Edahiro A, Ohara Y, Iwasaki M, Hayakawa M, Watanabe Y, Inagaki H, Kim H, et al: Relationship between eating alone and poor appetite using the Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire. Nutrients 2022; 14:337. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020337

Tani Y, Sasaki Y, Haseda M, Kondo K, Kondo N. Eating alone and depression in older men and women by cohabitation status: The JAGES longitudinal survey. Age Ageing 2015; 44:1019–1026. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv145

Sakurai R, Kawai H, Suzuki H, Kim H, Watanabe Y, Hirano H, Ihara K, Obuchi S, Fujiwara Y. Association of eating alone with depression among older adults living alone: Role of poor social networks. J Epidemiol 2021; 31:297–300. doi: https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20190217

Tani Y, Kondo N, Noma H, Miyaguni Y, Saito M, Kondo K. Eating alone yet living with others is associated with mortality in older men: The JAGES Cohort Survey. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2018; 73:1330–1334. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw211

Montagnese C, Santarpia L, Buonifacio M, Nardelli A, Caldara AR, Silvestri E, Contaldo F, Pasanisi F. European food-based dietary guidelines: a comparison and update. Nutrition 2015; 31:908–915. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2015.01.002

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 9th Edition. December 2020. Available at http://DietaryGuidelines.gov.

Sotos-Prieto M, Bhupathiraju SN, Mattei J, Fung TT, Li Y, Pan A, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Hu FB. Changes in diet quality scores and risk of cardiovascular disease among US men and women. Circulation 2015; 132:2212–2219. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017158

Sotos-Prieto M, Bhupathiraju SN, Mattei J, Fung TT, Li Y, Pan A, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Hu FB. Association of changes in diet quality with total and cause-specific mortality. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:143–153. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1613502

Matsuyama S, Zhang S, Tomata Y, Abe S, Tanji F, Sugawara Y, Tsuji I. Association between improved adherence to the Japanese diet and incident functional disability in older people: The Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study. Clin Nutr 2020; 39:2238–2245. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2019.10.008

Tomata Y, Watanabe T, Sugawara Y, Chou WT, Kakizaki M, Tsuji I. Dietary patterns and incident functional disability in elderly Japanese: The Ohsaki Cohort 2006 study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014; 69:843–851. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glt182

Kumagai S, Watanabe S, Shibata H, Amano H, Fujiwara Y, Shinkai S, Yoshida H, Suzuki T, Yukawa H, Yasumura S, Haga H. Effects of dietary variety on declines in high-level functional capacity in elderly people living in a community. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2003; 50:1117–1124 (in Japanese). doi: https://doi.org/10.11236/jph.50.12_1117

Yokoyama Y, Nishi M, Murayama H, Amano H, Taniguchi Y, Nofuji Y, Narita M, Matsuo E, Seino S, Kawano Y, Shinkai S. Association of dietary variety with body composition and physical function in community-dwelling elderly Japanese. J Nutr Health Aging 2016; 20:691–696. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-015-0632-7

Yokoyama Y, Nishi M, Murayama H, Amano H, Taniguchi Y, Nofuji Y, Narita M, Matsuo E, Seino S, Kawano Y, Shinkai S. Dietary variety and decline in lean mass and physical performance in community-dwelling older Japanese: A 4-year follow-up study. J Nutr Health Aging 2017; 21:11–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0726-x

Yokoyama Y, Kitamura A, Yoshizaki T, Nishi M, Seino S, Taniguchi Y, Amano H, Narita M, Shinkai S. Score-based and nutrient-derived dietary patterns are associated with depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older Japanese: A cross-sectional study. J Nutr Health Aging 2019; 23:896–903. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-019-1238-2

Seino S, Kitamura A, Tomine Y, Tanaka I, Nishi M, Nonaka K, Nofuji Y, Narita M, Taniguchi Y, Yokoyama Y, et al: A community-wide intervention trial for preventing and reducing frailty among older adults living in metropolitan areas: design and baseline survey for a study integrating participatory action research with a cluster trial. J Epidemiol 2019; 29:73–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20170109

Seino S, Tomine Y, Nishi M, Hata T, Fujiwara Y, Shinkai S, Kitamura A. Effectiveness of a community-wide intervention for population-level frailty and functional health in older adults: A 2-year cluster nonrandomized controlled trial. Prev Med 2021; 149:106620. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106620

Tsutsui T, Muramatsu N. Japan’s universal long-term care system reform of 2005: Containing costs and realizing a vision. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55:1458–1463. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01281.x

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2017) Terms of reference: OECD project on the distribution of household incomes (2017/18 collection). http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/IDD-ToR.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2022

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2020) Dietary reference intakes for Japanese (2020). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000862500.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2022

Hawton A, Green C, Dickens AP, Richards SH, Taylor RS, Edwards R, Greaves CJ, Campbell JL. The impact of social isolation on the health status and health-related quality of life of older people. Qual Life Res 2011; 20:57–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9717-2

Kobayashi E, Fukaya T. Change in prevalence of elderly social isolation and related factors: Findings from the National Survey of the Japanese Elderly in 1987, 1999, and 2012. Japanese Journal of Social Welfare 2015; 56:88–100 (in Japanese). doi: https://doi.org/10.24469/jssw.56.2_88

Takahashi T, Nonaka K, Matsunaga H, Hasebe M, Murayama H, Koike T, Murayama Y, Kobayashi E, Fujiwara Y. Factors relating to social isolation in urban Japanese older people: A 2-year prospective cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2020; 86:103936. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.103936

Hoyl MT, Alessi CA, Harker JO, Josephson KR, Pietruszka FM, Koelfgen M, Mervis JR, Fitten LJ, Rubenstein LZ. Development and testing of a five-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:873–878. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03848.x

Rinaldi P, Mecocci P, Benedetti C, Ercolani S, Bregnocchi M, Menculini G, Catani M, Senin U, Cherubini A. Validation of the five-item geriatric depression scale in elderly subjects in three different settings. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51:694–698. doi: https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00216.x

Suthutvoravut U, Tanaka T, Takahashi K, Akishita M, Iijima K: Living with family yet eating alone is associated with frailty in community-dwelling older adults. The Kashiwa Study. J Frailty Aging 2019; 8:198–204. doi: https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2019.22

Ishikawa M, Takemi Y, Yokoyama T, Kusama K, Fukuda Y, Nakaya T, Nozue M, Yoshiike N, Yoshiba K, Hayashi F, Murayama N: “Eating Together” is associated with food behaviors and demographic factors of older Japanese people who live alone. J Nutr Health Aging 2017; 21:662–672. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0805-z

Fukuda Y, Ishikawa M, Yokoyama T, Hayashi T, Nakaya T, Takemi Y, Kusama K, Yoshiike N, Nozue M, Yoshiba K, Murayama N. Physical and social determinants of dietary variety among older adults living alone in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2017; 17:2232–2238. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13004

Kobayashi M, Sasazuki S, Shimazu T, Sawada N, Yamaji T, Iwasaki M, Mizoue T, Tsugane S. Association of dietary diversity with total mortality and major causes of mortality in the Japanese population: JPHC study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2020; 74:54–66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-019-0416-y

Otsuka R, Tange C, Nishita Y, Kato Y, Tomida M, Imai T, Ando F, Shimokata H. Dietary diversity and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Japanese community-dwelling older adults. Nutrients 2020; 12:1052. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041052

Yamashita M, Seino S, Nofuji Y, Sugawara Y, Osuka Y, Kitamura A, Shinkai S: The Kesennuma Study in Miyagi, Japan. Study design and baseline profiles of participants. J Epidemiol 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20200599

Narita M, Kitamura A, Takemi Y, Yokoyama Y, Morita A, Shinkai S. Food diversity and its relationship with nutrient intakes and meal days involving staple foods, main dishes, and side dishes in community-dwelling elderly adults. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2020; 67:171–182 (in Japanese). doi: https://doi.org/10.11236/jph.67.3_171

Seino S, Nishi M, Murayama H, Narita M, Yokoyama Y, Nofuji Y, Taniguchi Y, Amano H, Kitamura A, Shinkai S. Effects of a multifactorial intervention comprising resistance exercise, nutritional and psychosocial programs on frailty and functional health in community-dwelling older adults: A randomized, controlled, cross-over trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2017; 17:2034–2045. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13016

Seino S, Nofuji Y, Yokoyama Y, Tomine Y, Nishi M, Hata T, Shinkai S, Fujiwara Y, Kitamura A. Impact of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on new applications for long-term care insurance in a metropolitan area of Japan. J Epidemiol 2021; 31:401–402. doi: https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20210047

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the residents and staff members of Ota City and to our collaborator, Yui Tomine.

Funding

Financial Support: This study was supported by grants from Ota City (no available number), the Japan Foundation for Aging and Health (no available number), and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number: 19H03914).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards Disclosure: The ethics committee of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology approved this study, which complies with the current laws of Japan.

Additional information

Authorship: Study concept and design: Toshiki Hata, Satoshi Seino, Akihiko Kitamura, and Yoshinori Fujiwara; Acquisition of data: Toshiki Hata, Satoshi Seino, Mariko Nishi, Shoji Shinkai, Akihiko Kitamura, and Yoshinori Fujiwara; Analysis and interpretation of data: Toshiki Hata, Satoshi Seino, Akihiko Kitamura, and Yoshinori Fujiwara; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Toshiki Hata, Satoshi Seino, Yuri Yokoyama, Miki Narita, Mariko Nishi, Azumi Hida, Shoji, Shinkai, Akihiko Kitamura, and Yoshinori Fujiwara; Statistical analysis: Toshiki Hata; Study supervision: Yoshinori Fujiwara.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hata, T., Seino, S., Yokoyama, Y. et al. Interaction of Eating Status and Dietary Variety on Incident Functional Disability among Older Japanese Adults. J Nutr Health Aging 26, 698–705 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-022-1817-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-022-1817-5