Abstract

Objectives

Anticholinergic burden defined by the Anticholinergic Risk Scale (ARS) has been associated with cognitive and functional decline. Associations with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) have been scarcely studied. The aim of this study was to examine the association between anticholinergic burden and HRQoL among older people living in long-term care. Further, we investigated whether there is an interaction between ARS score and HRQoL in certain underlying conditions.

Design and participants

Cross-sectional study in 2017. Participants were older people residing in long-term care facilities (N=2474) in Helsinki.

Measurements

Data on anticholinergic burden was assessed by ARS score, nutritional status by Mini Nutritional Assessment, and HRQoL by the 15D instrument.

Results

Of the participants, 54% regularly used ARS-defined drugs, and 22% had ARS scores ≥2. Higher ARS scores were associated with better cognition, functioning, nutritional status and higher HRQoL. When viewing participants separately according to a diagnosis of dementia, nutritional status or level of dependency, HRQoL was lower among those having dementia, worse nutritional status, or being dependent on another person’s help (adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities). Significant differences within the groups according to ARS score were no longer observed. However, interactions between ARS score and dementia and dependency emerged.

Conclusion

In primary analysis there was an association between ARS score and HRQoL. However, this relationship disappeared after stratification by dementia, nutritional status and dependency. The reasons behind the interaction concerning dementia or dependency remain unclear and warrant further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Older people residing in long-term care are living the last years of their lives (1). They are likely to have cognitive impairment, deficits in physical functioning, and multiple coexisting diseases (1, 2). Their diseases are often chronic (2), and thus, the aim of the care is in most cases palliative, i.e. to maintain or improve quality of life (QoL). Health-related quality of life (HRQoL), recognized as a relevant aspect of QoL, consists of physical, emotional, and social dimensions associated with a person’s illnesses and their treatment (3).

Potentially inappropriate medications are widely used among older people living in long-term care facilities (4, 5). Most drugs with anticholinergic properties (DAPs) are considered potentially inappropriate according to American Geriatrics Society Beers criteria (6), and thus, should be avoided in older adults. Despite this recommendation, DAPs remain frequently used among older nursing home residents (7–11). DAPs may cause adverse effects on both central and peripheral nervous systems (12). Dry mouth, dry eyes, constipation, dizziness, cognitive decline, and falls are some of the common adverse effects (13, 14). Several studies have reported an association between anticholinergic burden and physical impairment (15). In a recently published study, even a relationship between use of certain DAPs and increased risk of dementia has been suggested (16). Polypharmacy among older people living in long-term care is common (17), leading easily to a situation in which several DAPs are present, increasing the anticholinergic burden. Unwanted side-effects tend to increase hand in hand with greater anticholinergic burden (18).

There is a scarcity of studies exploring the relationship between anticholinergic drug use and HRQoL in older people, and the results are somewhat inconclusive. Studies among community dwelling older people have reported an association between anticholinergic drug use and the lower physical component score of HRQoL according to SF-12/SF-36 (19, 20). In studies among older long-term care residents with high prevalence of cognitive impairment, exposure to anticholinergic and sedative drugs defined by the Drug Burden Index has shown to have an inverse association with QoL (5, 21). However, in one American study investigating a nursing home population, no association between anticholinergic burden and engagement in activities, an important indicator of QoL, was observed (7). There is some evidence, that among older long-term care residents DAP use is associated with decreased well-being, which can be considered an aspect of HRQoL (22, 23).

Despite the importance of the topic, limited research exists on the association between DAP use and HRQoL among long-term care residents. Our hypothesis was that greater anticholinergic burden would have an association with lower HRQoL. The rationale behind our hypothesis was that the common side-effects of DAPs may be associated with lower HRQoL. Especially residents with dementia are likely to be vulnerable to the harmful effects of DAPs such as cognitive decline (24).

The aim of our study was to investigate the association between anticholinergic burden, defined by the Anticholinergic Risk Scale (ARS) (14), and HRQoL according to 15D (3). A second aim was to determine whether certain underlying conditions such as dementia, nutritional status or dependency on personal care have an interaction with the relationship between 15D and ARS score.

Methods

All residents living in all long-term care facilities (including nursing homes and assisted living facilities) in Helsinki in 2017 were invited to participate (N=3895). Exclusion criteria were patient refusal, or having dementia and no proxy available to give informed consent. Because the aim was to assess the burden arising from DAP use, we excluded residents not using regularly any medications or those whose medication list was not available. After exclusions, 2474 participants remained.

A trained, registered nurse performed the assessments and interviews according to a structured study protocol. The data were collected in March 2017, and each resident was assessed over the course of one day. The medication list was a point-prevalence on the same day. Medications were retrieved from participants’ medical charts.

All medications used were classified by the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System (25). Only medications administered regularly were included. As described in previous research, regularly used drugs were considered to be those for which there was a documented regular sequence of administration (26). Thus, medications given pro re nata, were not taken into account. DAPs were defined by the ARS, which is a list of 49 commonly used drugs with anticholinergic potential (14). The ARS ranks medications on a 3-point scale (0=limited or none; 1=moderate; 2=strong; 3=very strong anticholinergic potential). The total ARS score is the sum of the points of individual medications. However, the scale does not consider the dosage of an individual drug. Among older people, even a moderate change in the ARS score has been suggested to have an association with cognitive and functional decline (27); hence, we grouped the participants into four groups from none (G0) to very strong (G3) anticholinergic potential defined by the ARS to view also the participants with moderate anticholinergic burden. The ARS has been used in several studies particularly involving nursing home residents, and it has been shown to have an association with outcomes in cognitive performance and physical function (9, 28, 29).

In each long-term care unit, background data on demographics, medical diagnoses (acute illnesses and chronic conditions) were retrieved from medical charts.

The severity of dementia was assessed by using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) “memory” item [30] and the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (31). The CDR “memory” item grades stages of cognition on a 5-point scale (0=no memory loss; 0.5=consistent slight forgetfulness; 1=moderate memory loss; 2=severe memory loss; 3=severe memory loss, only fragments remain) (30). MMSE is a screening tool for dementia, which also can be used in measuring cognitive impairment, yielding a score from 0 to 30 (31). Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) was applied to assess participants’ nutritional status (32). Dependency in activities of daily living (ADL) was assessed by a 4-point scale according to the CDR “personal care” item (1=totally independent; 2=needs prompting; 3=requires assistance in dressing, personal hygiene, and keeping of personal belongings; 4=requires much help with personal care, often incontinent) (30). Those in groups 3 and 4 were considered to be dependent for personal care.

The main outcome of our study was HRQoL assessed by the 15D instrument, which explores health state in 15 dimensions (mobility, vision, hearing, breathing, sleeping, eating, speech, excretion, usual activities, mental function, discomfort and symptoms, depression, distress, vitality, sexual activity) (3). The 15D is a validated instrument for use in various populations and health problems (3). It is primarily meant to be filled in by the respondent, but interview or proxy administration is also possible. 15D can be generated to a 15D score as an index measure in which the minimum score is 0 (being dead) and the maximum score is 1 (no problems on any dimension) (3).

Statistics

The results are presented as means with standard deviations (SDs) or as counts with percentages. To evaluate the relationship of anticholinergic burden with HRQoL, we divided the participants into groups according to anticholinergic burden defined by ARS score (14) as follows: GO, ARS score=0; G1, ARS score=1; G2, ARS score=2; and G3, ARS score ≥3. Furthermore, we stratified the respective groups according to dementia diagnosis, nutritional status and dependency for personal care to investigate whether they have an interaction with the relationship between ARS score and HRQoL.

Statistical significance for the unadjusted hypothesis of linearity across categories (quartiles) of ARS score and characteristics of the study participants were evaluated using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and logistic (ordinal) models with an appropriate contrast. Adjusted (age, sex and CCI) relationship between ARS score and dementia diagnosis, nutritional status, and dependency in personal care with 15D was analyzed using two-way analysis of variance. In cases of violation of assumptions (e.g. non-normality), a bootstrap-type test was used. Normality of variables was evaluated graphically and using the Shapiro-Wilk W test. Stata 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for the analysis.

Results

The participants were divided into four groups according to the ARS score [G0 (n=1149); G1, (n=768); G2 (n=347); G3 (n=210)]. Of all participants, 1149 (46%) did not use any ARS-defined DAPs, and thus had an ARS score of 0 (G0); 31% scored 1 point (G1), 14% 2 points (G2), and 8% 3 or more points (G3). A greater ARS score was associated with younger age and a lower proportion of females. Those having higher ARS scores suffered more often from depression, other psychiatric illnesses, and Parkinson’s disease. The greater the ARS score, the greater the number of drugs used on a regular basis. The number of ARS-defined drugs increased alongside greater anticholinergic burden; in G1, the mean number was 1.0, in G2 1.6, and in G3 2.1. The most frequently used ARS-defined drug groups were antipsychotics (33%) and antidepressants (23%).

Altogether, 1899 residents (77%) had a dementia diagnosis, whereas 575 (23%) did not. Along with greater ARS scores, a decreasing trend in the proportion of participants with a diagnosis of dementia was observed: in G0 78%, in Gl 82%, in G2 75%, and in G3 56% (p<0.001). An increasing trend in MMSE points with greater ARS scores was observed, indicating better cognition, and CDR also suggested milder cognitive impairment with higher ARS scores. Residents with higher ARS scores had better nutritional status than those with a lower ARS score. A decreasing trend in dependency on personal care with a greater ARS score was observed. 15D scores showed an increasing trend with ARS scores, thus indicating better HRQoL among those with a greater anticholinergic burden (Table 1).

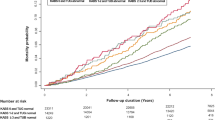

To further investigate whether cognitive or functional decline had an interaction with the relationship between ARS score and HRQoL, we then stratified the participants according to a diagnosis of dementia, nutritional status, and those dependent on personal care. Between the ARS-score groups, significant differences in HRQoL were no longer observed. Overall, residents with dementia had lower 15D scores, indicating poorer HRQoL, versus those without dementia. Residents at risk of malnutrition or being malnourished had lower 15D scores than residents with good nutritional status (p<0.001), and the same pattern was observed in residents with functional dependency compared with those not dependent on personal care (p<0.001). Interactions between ARS score and dementia, and ARS score and dependency emerged, indicating different directions of trend in HRQoL in these two groups. Among those with dementia or dependency, 15D scores increased along with ARS scores, whereas they decreased among those without dementia and those who were not dependent. No significant interaction as regards nutritional status was observed (Figure 1).

Relationship between anticholinergic burden measured by the Anticholinergic Risk Scale (ARS) score and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measured by 15D score among residents with and without dementia diagnosis; at risk for malnutrition or malnourished and well-nourished; and dependent and not dependent. Adjusted for age, sex and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)

We further explored the group of people with dementia. Among those with no anticholinergic burden (ARS score 0), the mean MMSE score was 11.2, whereas among those with dementia and ARS score ≥3, the respective figure was 13.7. Of those with dementia, most of the burden was associated with psychotropics, since 115/117 participants were on these drugs. Antipsychotic drugs were particularly common among them (80/117). Those without dementia suffered from psychiatric illnesses (n=46), stroke (n=24), Parkinson’s disease (n=8), or ALS/MS (n=7). Nearly all of them were administered psychotropics (92/93) as well.

Discussion

Our primary analysis suggested an association between higher anticholinergic burden and better health status in terms of cognition, nutrition, functioning and HRQoL. However, after stratification, no significant differences in HRQoL between the ARS-score groups remained. Furthermore, surprising interactions in the trends of 15D scores were observed in the groups stratified according to a diagnosis of dementia, and dependency as regards personal care. Among residents with dementia or dependency, the trend in HRQoL scores increased with greater ARS score, whereas the trend was in the opposite direction among residents without dementia and those who were not dependent.

The proportion of DAP users was consistent with those in earlier studies in which it has varied between 48% and 65% among nursing home residents (9, 33). The ARS score was associated with a higher number of drugs used, which is also in line with observations in previous studies (9, 34). We included only residents using at least one drug regularly, so the proportion of DAP users might be a slight overestimation of the true situation.

In the primary analysis, our finding of an increasing trend of HRQoL along with increasing anticholinergic burden was surprising and not in line with the results of previous studies (5, 21–23). Hence, we further stratified our sample according to various health conditions, ARS scores and HRQoL. After stratification and adjustments, the relationship between ARS score and HRQoL no longer existed. Irrespective of the ARS score, dementia, malnutrition and dependency were all associated with lower HRQoL, suggesting that these conditions are explanatory factors. These findings are in line with those in a prior study showing that the severity of dementia is associated with poorer QoL (35). Our findings concerning the associations between poorer HRQoL and malnutrition or dependency are also supported by existing evidence from previous studies (36–38).

The trend in ARS scores differed among those with and without dementia. Although it is challenging to determine whether it is the ARS score or the characteristics of participants that influences HRQoL, we explored the characteristics of our groups of participants. Those without dementia suffered from other psychiatric illnesses such as depression or chronic psychosis. Furthermore, almost all of them were administered psychotropic drugs. Thus, either the high burden of psychotropics is harmful in this patient group or the severity of these diseases has a negative impact on HRQoL. Because of the cross-sectional nature of the study it is impossible to draw definite conclusions on which explanation holds true.

On the other hand, among those with dementia and dependency the 15D score increased along with anticholinergic burden. It seems that participants with dementia and higher ARS scores had better cognition and functioning, thus resulting in higher 15D scores. Thus, those with the most severe dementia might be spared a high anticholinergic burden. A large proportion of those with high ARS scores had been given psychotropics and antipsychotics, suggesting that they might suffer from neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Our study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first one carried out in order to investigate the associations and interaction between anticholinergic burden, HRQoL and overall health status in connection with dementia, nutritional status and functional dependency among residents living in long-term care facilities. Our sample is large and well representative of older residents in long-term care in Helsinki. Because the medications were administered by nurses, drug use according to drug lists can be considered reliable. Data were collected from residents’ medical records, and measurements were performed by trained nurses according to a standardized study protocol. The 15D instrument is a standardized and validated measure (3) showing high-level correlation with other HRQoL instruments such as EQ-5D and SF6D (39).

As a limitation, the cross-sectional nature of our study allows us only to report associations within the cohort. Although interactions and associations exist between ARS score, HRQoL and cognitive decline, nutritional status and dependency, it is not possible to draw any conclusions about causal relationships. Thus, we must emphasize that confounding by indication may be behind the findings of our study. Cognitive impairment in our population was common, and thus the 15D questionnaire was mainly completed by an interviewer or via proxy administration. Although caution in using a proxy respondent in measuring HRQoL has been suggested (40), the 15D instrument has been evaluated and shown to be reliable when used in this manner (3). Proxy administration enabled us to include persons with severe dementia, in order to have a more real-life spectrum of nursing home residents. Another limitation is that we used only one anticholinergic scale. While a number of scales exist, there is considerable discordance between them. Thus, the results and outcomes might have been different had a scale other than the ARS been used (28, 29). However, the ARS scale is widely used, particularly among nursing home residents (29).

Conclusion

Whereas in the primary analysis there was an association between anticholinergic burden defined by the ARS, and HRQoL measured by the 15D instrument, this relationship disappeared when the participants were stratified according to dementia, nutritional status and dependency. Interaction in the dementia and dependency groups was observed. The reasons behind this interaction remain unclear, warranting further studies.

References

Pitkälä KH, Juola AL, Kautiainen H, et al. Education to reduce potentially harmful medication use among residents of assisted living facilities; a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014 Dec;15(12):892–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.04.002.

Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10:430–439. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003

Sintonen H. The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med 2001;33:328–36.

Colloca G, Tosato M, Vetrano DL, et al. Inappropriate Drugs in Elderly Patients with Severe Cognitive Impairment: Results from the Shelter Study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e46669. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046669.

Harrison SL, Kouladjian O’Donnell L, Bradley CE, et al. Associations between the Drug Burden Index, Potentially Inappropriate Medications and Quality of Life in Residential Aged Care. Drugs Aging 2018;35:83–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0513-3.

American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:674–694. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15767

Kolanowski A, Fick DM, Campbell J, Litaker M, Boustani M. A preliminary study of anticholinergic burden and relationship to a quality of life indicator, engagement in activities, in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2009;10:252–257. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2008.11.005.

Chatterjee S, Mehta S, Sherer JT, Aparasu RR. Prevalence and predictors of anticholinergic medication use in elderly nursing home residents with dementia: analysis of data from the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey. Drugs Aging. 2010;27:987–97.

Landi F, Dell’Aquila G, Collamati A, et al. Anticholinergic drug use and negative outcomes among the frail elderly population living in a nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:825–829.

Palmer JB, Albrecht JS, Park Y, et al. Use of drugs with anticholinergic properties among nursing home residents with dementia: a national analysis of Medicare beneficiaries from 2007 to 2008. Drugs Aging 2015;32:79–86.

Aalto UL, Roitto HM, Finne-Soveri H, Kautiainen H, Pitkälä KH. Temporal trends in the use of anticholinergic drugs among older people living in long-term care facilities in Helsinki. Drugs Aging 2020;37,27–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40266-019-00720-6

Tune LE. Anticholinergic effects of medication in elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62 Suppl 21:11–14.

Mintzer J, Burns A. Anticholinergic side-effects of drugs in elderly people. J R Soc Med 2000;93:457–62

Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:508–513.

Cardwell K, Hughes CM, Ryan C. The association between anticholinergic medication burden and health related outcomes in the ‘Oldest Old’: a systematic review of the literature. Drugs Aging. 2015;32:835–48.

Coupland CAC, Hill T, Dening T, Morriss R, Moore M, Hippisley-Cox J. Anticholinergic Drug Exposure and the Risk of Dementia: A Nested Case-Control Study. JAMA Intern Med 2019.: doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0677.

Onder G, Liperoti R, Fialova D, et al. Polypharmacy in Nursing Home in Europe: results from the SHELTER Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2012;67(6):698–704. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glr233

Salahudeen MS, Duffull SB, Nishtala PS. Anticholinergic burden quantified by anticholinergic risk scales and adverse outcomes in older people: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:31.

Sura SD, Carnahan RM, Chen H, Aparasu RR. Anticholinergic drugs and health-related quality of life in older adults with dementia. J Am Pharm Assoc 2015;55:282–287. doi: https://doi.org/10.1331/JAPhA.2015.14068.

Cossette B, Bagna M, Sene M, et al. Association Between Anticholinergic Drug Use and Health-Related Quality of Life in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Drugs Aging 2017;34:785–792. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0486-2.

Bosboom PR, Alfonso H, Almeida OP, Beer C. Use of potentially harmful medications and health-related quality of life among people with dementia living in residential aged care facilities. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra 2012;2:361–371.

Teramura-Grönblad M, Muurinen S, Soini H, Suominen M, Pitkälä KH. Use of anticholinergic drugs and cholinesterase inhibitors and their association with psychological well-being among frail older adults in residential care facilities. Ann Pharmacother 2011;45:596–602. doi: https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1P650.

Aalto UL, Roitto HM, Finne-Soveri H, Kautiainen H, Pitkälä KH. Use of Anticholinergic Drugs and its Relationship With Psychological Well-Being and Mortality in Long-Term Care Facilities in Helsinki. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:511–515. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.11.013.

Fox C, Smith T, Maidment I, et al. Effect of medications with anti-cholinergic properties on cognitive function, delirium, physical function and mortality: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):604–615. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu096

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification index with DDDs, 2019. Oslo, Norway 2018.

Hosia-Randell HM, Muurinen SM, Pitkala KH. Exposure to potentially inappropriate drugs and drug-drug interactions in elderly nursing home residents in Helsinki, Finland: a cross-sectional study. Drugs Aging 2008;25:683–92

Brombo G, Bianchi L, Maietti E, et al. Association of anticholinergic drug burden with cognitive and functional decline over time in older inpatients: results from the CRIME project. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:917–924.

Pasina L, Djade CD, Lucca U, et al. Association of anticholinergic burden with cognitive and functional status in a cohort of hospitalized elderly: comparison of the anticholinergic cognitive burden scale and anticholinergic risk scale: results from the REPOSI study. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:103–12.

Welsh TJ, van der Wardt V, Ojo G, Gordon AL, Gladman JRF. Anticholinergic drug burden tools/scales and adverse outcomes in different clinical settings: a systematic review of reviews. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:523–538.

Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98.

Vellas B, Guigoz Y, Garry PJ, et al. The mini nutritional assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Nutrition 1999;15:116–122.

Niznik J, Zhao X, Jiang T, et al. Anticholinergic Prescribing in Medicare Part D Beneficiaries Residing in Nursing Homes: Results from a Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis of Medicare Data. Drugs Aging 2017;34:925–939.

Sumukadas D, McMurdo ME, Mangoni AA, Guthrie B. Temporal trends in anticholinergic medication prescription in older people: repeated cross-sectional analysis of population prescribing data. Age Ageing. 2014 Jul;43(4):515–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft199.

Mjørud M, Kirkevold M, Røsvik J, Selbæk G, Engedal K. Variables associated to quality of life among nursing home patients with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(8):1013–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.903468.

Rasheed S, Woods RT. Malnutrition and quality of life in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(2):561–566. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2012.11.003

Jiménez-Redondo S, Beltrán de Miguel B, Gavidia Banegas J, Guzmán Mercedes L, Gómez-Pavón J, Cuadrado Vives C. Influence of nutritional status on health-related quality of life of non-institutionalized older people. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18(4):359–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-013-0416-x

Wang P, Yap P, Koh G, et al. Quality of life and related factors of nursing home residents in Singapore. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0503-x

Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Day NA. A comparison of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) with four other generic utility instruments. Ann Med 2001;33:358–370.

Andresen EM, Vahle VJ, Lollar D. Proxy reliability: health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures for people with disability. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:609–19

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by the City of Helsinki and the Finnish Medical Foundation. The funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; on in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ contributions: design/conduct of the study (UA, HFS, HÖ, HMR, KHP); analysis of data (UA, HK, KHP), interpretation of data (UA, HK, KHP); preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript (UA, HFS, HK, HÖ, HMR, KHP).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by Helsinki University Central Hospital Ethics Committee. Participants or, in case of moderate-severe dementia, their closest proxy gave informed consent.

Rights and permissions

Open Access: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aalto, U.L., Finne-Soveri, H., Kautiainen, H. et al. Relationship between Anticholinergic Burden and Health-Related Quality of Life among Residents in Long-Term Care. J Nutr Health Aging 25, 224–229 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1493-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1493-2